Introduction

Carbon is able to form a wide variety of stable structures including diamond, graphite, fullerenes, nanotubes, onions, amorphous materials, ribbons, carbon chains, carbon flowers, nano sponges all of which consist of a network of carbon atoms in different hybridisation states, sp3, sp2 or sp1, intermixed in different proportions.1-7 For instance, carbon nanotubes and graphene consist of primarily sp2-hybridised carbon, with a small proportion of sp3- or sp1-hybridised carbon atoms at sites of defects or along the edges,8-11 where as nanodiamonds that primarily comprise sp3-hybridised carbon often contain some sp2-hybridised carbon atoms on the surface.12 Furthermore, due to a sharp nanoscale curvature of some carbon materials, the atoms may exist in intermediate hybridisation states, such as the case of C60 fullerene where carbon is neither sp2 nor sp3-hybridised.13

In recent years, atomic carbon chains have acquired much attention as they are considered to be the ultimate nanowire, i.e. mechanically robust,14 highly conducting15-17 and with tuneable electronic properties.15-17 Isolated carbon and boron nitride chains have been shown to be stable in vacuum inside the column of a transmission electron microscope (TEM) or encapsulated within carbon nanotubes.18-21 However, in bulk, the atomic chains are expected to be highly unstable and undergo cross-linking22 with methodologies for the controlled fabrication and stabilisation of pure carbyne remaining inaccessible.

In this study, we have demonstrated a new form of nanoscale species in the shape of half dome structures (CN@HDS) with the bonding characteristics of either sp1 or sp2 carbon nitride. The CN@HDS are formed spontaneously at high temperature in a dedicated heating stage in a transmission electron microscope from N(CH3)4OH adsorbed on the surface of colloidal Fe2O3 nanoparticles during the combustion Fe2O3 is reduced to Fe. The capping agent (surfactant) was still strongly bonded to the surfaces of the nanoparticles while it was reacting with few layer boron nitride sheets to form the CN@HDS. This new method of synthesis has demonstrated unprecedented levels of control over the CN@HDS formation, as thermally driven Ostwald ripening and particles migration of the metal particle provides for precise control of the CN@HDS, whilst the propensity of FeNPs to catalyse the formation of CN@HDS containing cynapolyynes species has been shown for the first time. The coexistence of carbon nitride atoms in two well-defined hybridisation states within the CN@HDS may offer functional features characteristic of carbyne (tuneable electronic band gap) and graphene (high mobility of charge carriers) as they can also be grown on graphene, thus opening a wealth of opportunities for practical applications as miniaturized opto-electronic, computing devices, and gas storage devices.23-31

Results

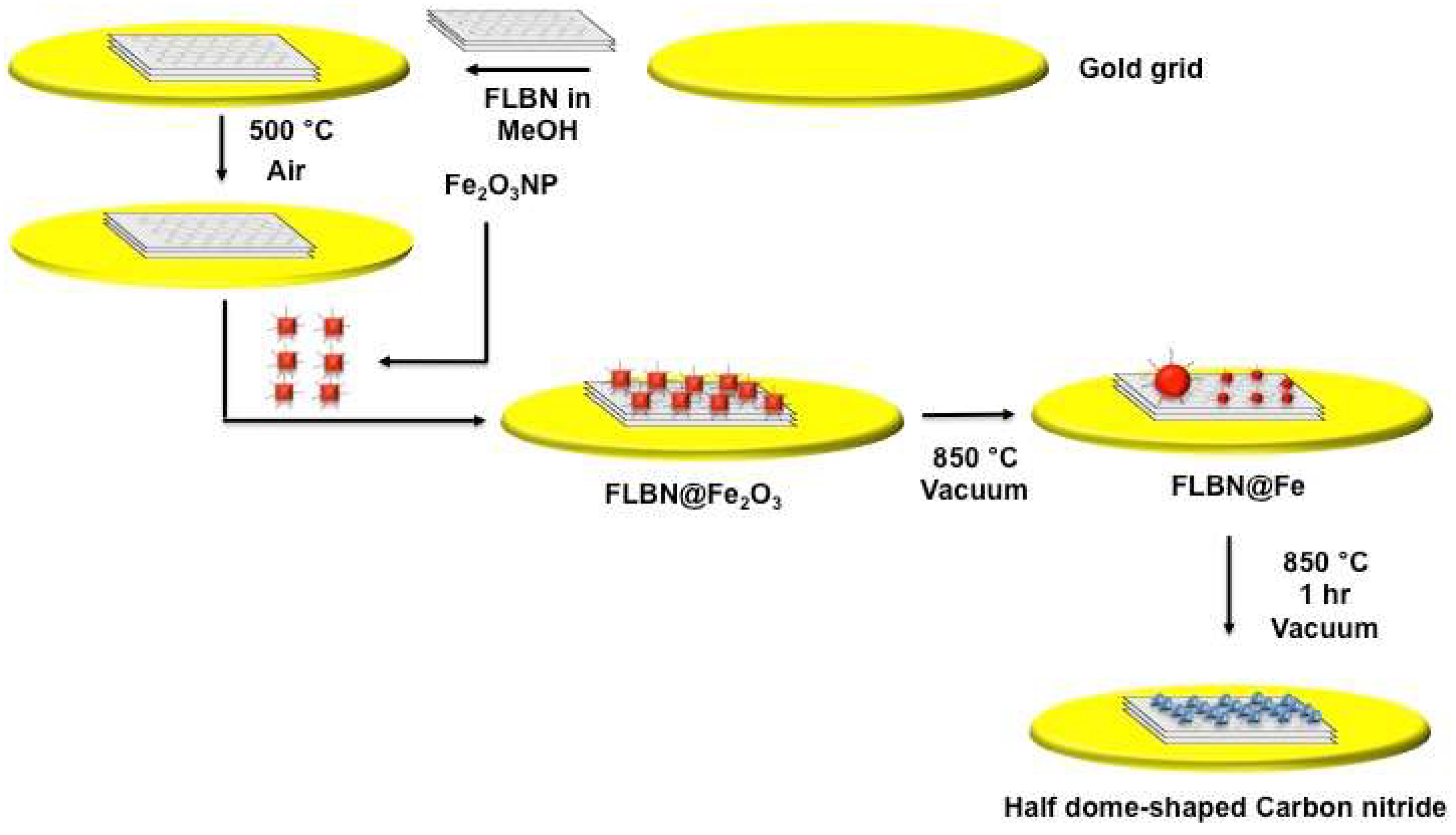

Hexagonal boron nitride sheets (of lateral size 50-200 nm and thickness 1-10 layers) (FLBN) deposited on a gold mesh finder grid of a TEM were heated in air at 500 °C to remove adventitious carbon. Iron oxide nanoparticles Fe

2O

3 (average size of 11.2 ± 0.5 nm) capped with tetra methyl ammonium hydroxide N(CH

3)

4OH were deposited from solution onto freshly FLBN sheets on a TEM grid (

Figure 1 and

Figure S2a). Raman spectroscopy carried out on freshly FLBN showed (

Figure S1) a single sharp band at 1363 cm

-1 characteristic of an h-BN phase and the EELS analysis confirmed the absence of advantageous carbon (

Figure S2).

32

The iron oxide nanoparticles Fe

2O

3 capped with tetra methyl ammonium hydroxide N(CH

3)

4OH were deposited form solution onto freshly FLBN on a TEM grid. The TEM grid was inserted in a dedicated TEM heating stage holder and heated at 850 °C for 30 minutes (

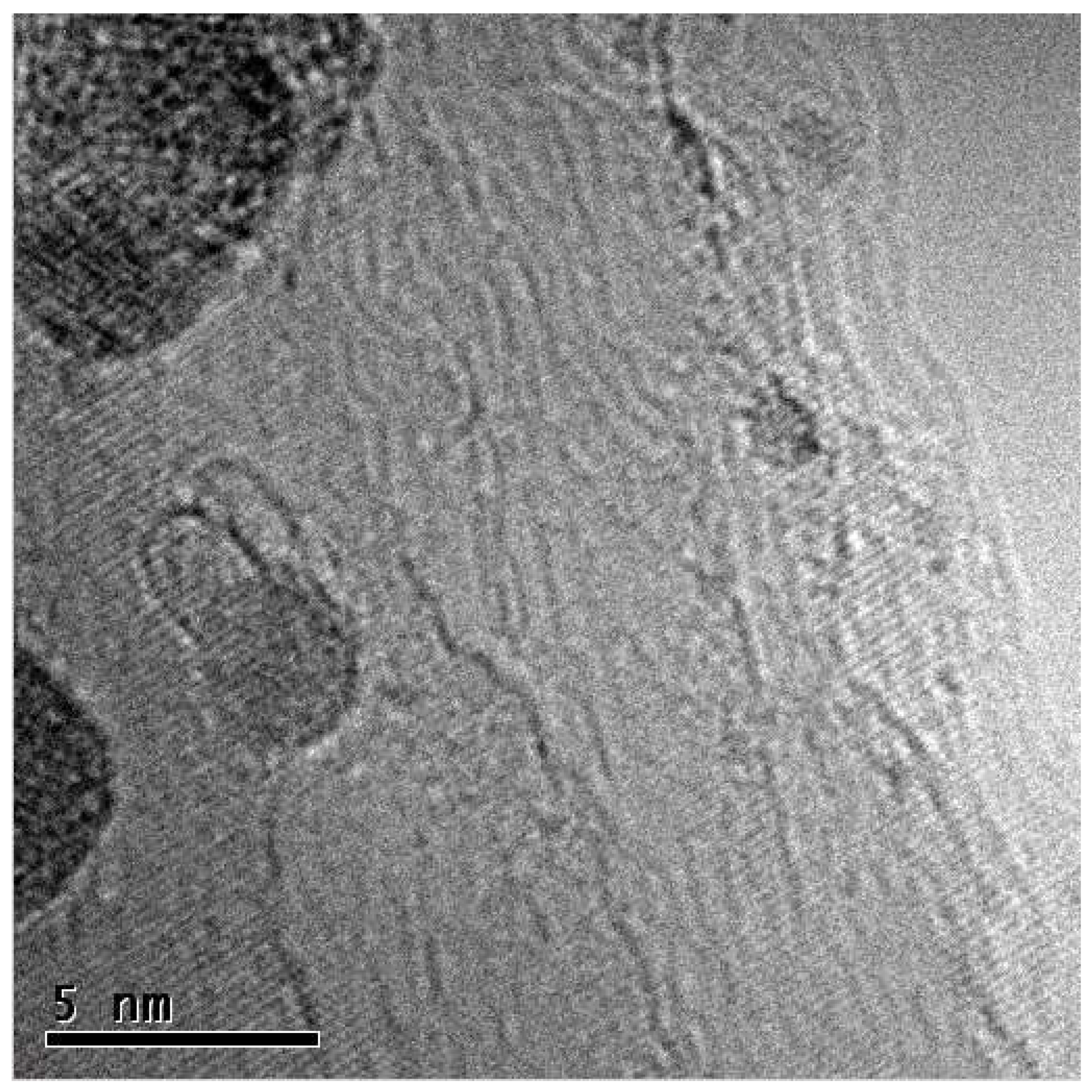

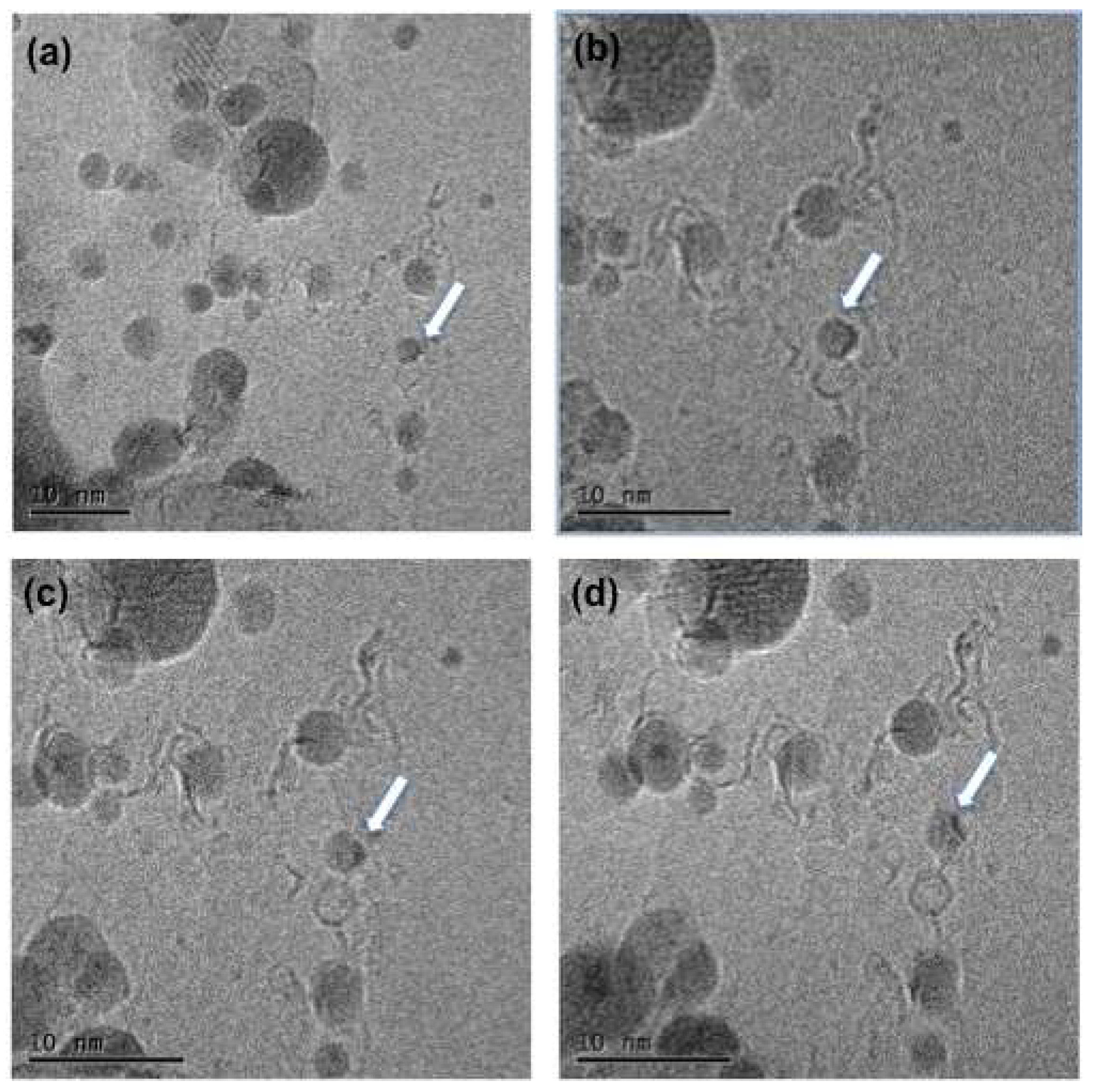

Figure 1). The TEM images clearly shows the CN@HDS protruding the iron nanoparticle (

Figure 2). Under this condition, we have been able to image the formation of CN@HDS in real time. The FeNP post their reduction commenced the ripening processes in which smaller nanoparticles were migrating towards bigger nanoparticle (

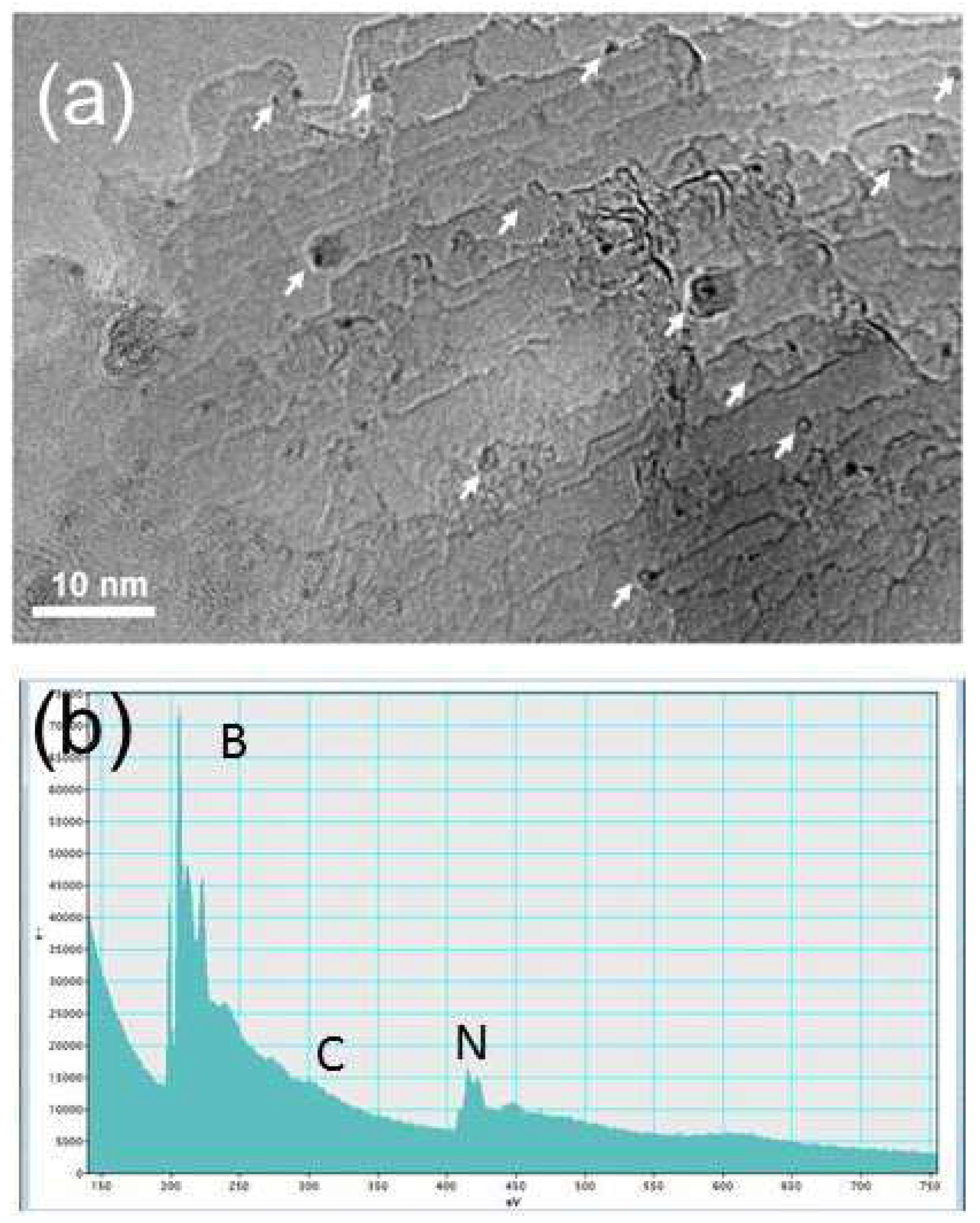

Figure S2b). During this migration process the small nanoparticles come across the step edges of the FLBN the CN@HDS were formed (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The small nanoparticle escaped from the CN@HDS dome structure migrating towards the big nanoparticle leaving behind part of the organic capping agent (

Figure 5 video file 2). Analysing the sample after 1 hr, the CN@HDS structures were present at the step edges of the FLBN as EELS measurement clearly show a feature in the region at 284,5 eV and the K edge at 292 eV. (

Figure 3b–

Figure 4d and

Figure S6). Raman spectroscopy of the CN@HDS structures formed on FLBN showed a D-band and G-band at 1350 (D1) and 1593 cm

-1 (G2), respectively (

Figure S8). The Raman spectroscopy also shows an intense peak at 2200 cm

-1 characteristic of CN sp

1 and a 2D band peak at 2700 cm

-1 characteristic of CN sp

2.

23

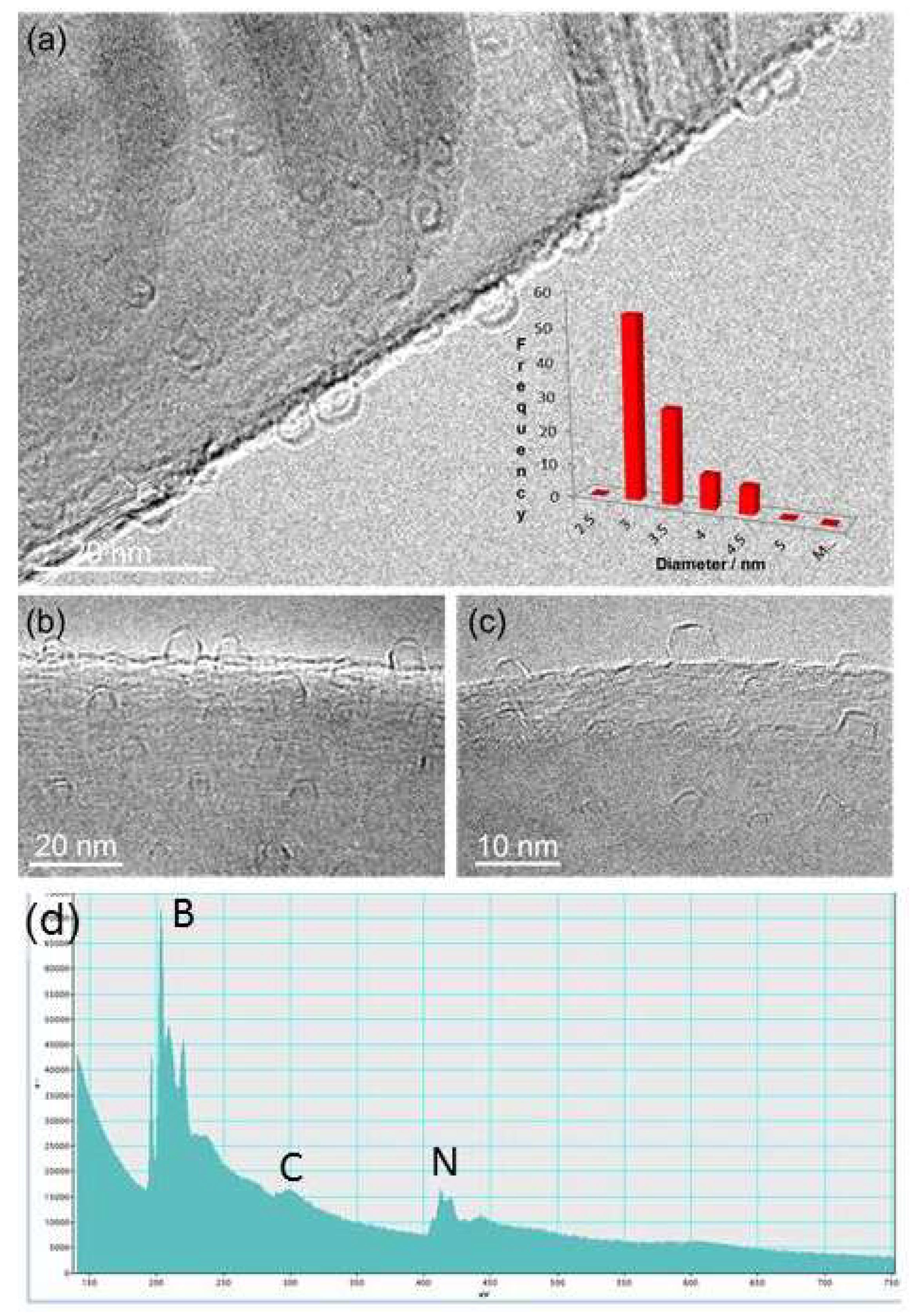

In a control experiment, it was verified the possibility to form CN@HDS structure containing nitrogen using a carbon support. We have used the same heating condition for the Fe

2O

3@FLBN hybrid inside the column of a TEM microscope. Detailed STEM-EELS analysis carried out on the CN@HDS revealed the presence of nitrogen with a ratio of 1 Nitrogen atom to 4 Carbon atoms as the source of Nitrogen of the BN was not present in this experiment (

Figure S4). Conversely, when the half dome structure were grown on few layer boron nitride sheets, the organic base during the combustion process catalysed by iron, reacted with the few layer boron nitride sheet allowing the uptake of nitrogen atoms to form cyanopolyynes with a ratio of 1 atom of nitrogen to 1 atom of carbon (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 and

Figure S9).

It was also noticed that when the nanoparticles runs out of the capping agent, they become naked and commenced to interact with the surfaces of FLBN either on the step edges or the flat surfaces to form BN@HDS. It was considered that Fe atom clusters originating from the large Fe NP’s (>30 nm) diffuse and become trapped along the dangling bonds and defect sites of BN step-edges. TEM images and simulated TEM images show that the morphologies of these BN@HDS nanostructures are distinct from their carbon analogues, requiring squares, pentagons, hexagons, heptagons and octagonal rings in their formation.

48 On the contrary to the CN@HDS half dome structure, the BN-half dome structures display sharp corners and edges (

Figure 4c and

Figure S12).

48 Discussion

Nobel metal nanoparticles has already shown the ability of catalysing the formation of carbon forms contain sp1/sp2 carbon as was recently shown by Kutrovskaya S. et al. under an effect of laser irradiation and electromagnetic fields using gold nanoparticles.33 A similar methodology was reported by Casari et al., noble metals particles have shown a high affinity to form carbon structure containing H-terminated polyyne.34 Okada et. al. have shown the possibility to produce a polymeric composite containing polyyne stabilised by silver nanoparticles.35 Carbon films enriched with carbyne species can be produced either via Chemical vapour deposition or Physical vapour deposition.15 It has also been shown that the dechlorination of Polyvinylidene chloride formed polyyne-polyene carbon films. Recently, a new generation of N-doped carbons have been found to be interesting materials because of their superior physical and chemical properties as compared to those of their undoped counterparts. Accordingly, wide ranges of applications are anticipated for these nitrogen-doped carbon materials such as anodes in high performance lithium ion batteries, high performance supercapacitors, as an adsorbent to be exploited for removing toxic pollutants from water. In addition, carbon nitride materials can provide large number of anchoring point sites adsorption for positive charged metal ions due to the electronegativity difference between N and C atoms in CN@HDS sp2 hybridization.12,15,23

The current literature report on the propensity of Nobel metals to form carbon forms containing sp

1/sp

2, the possibility that FeNPs are able to catalyse the formation of such carbon nitride forms has never been reported previously. During the temperature increase in our experiments, from 20

°C to 850

°C in vacuum, N(CH

3)

4OH is expected to undergo significant structural transformations, the N(CH

3)

4OH transforms to nitrile N(CH)

3 and CH

3OH (E2 Reaction), the alcohol evaporate and the nitriles begin its transformation forming cyano groups that reacts specifically with unsaturated carbon atoms, the support FLBN provide for a source of nitrogen atom that is required to form cyanopolyynes with the ratio of 1 carbon atom to 1 nitrogen atom (

Figure S13). The unsaturated carbon formation can be explained, as C-H bonds at around 300

°C, begin to dissociate, transforming the alkyl chains to alkene, polyene and polyyne and cumulenic chains, thus gradually converting sp

3-hybridised carbon to sp

1-hybridised carbon. However, as sp

1 chains are predicted to react with each other,

21 the close proximity of the molecules within half dome structures in our experiments, are likely to trigger cross-linking of the chains, leading to the formation of 2D material with CN sp

2 regions interconnected by sp

1-hybridised CN chains (

Figure S9) stabilised by positive charge over the nitrogen atoms. Such cross-linking immobilises the carbon material around the metal core, preventing desorption of the molecules, whilst de-hydrogenation continues as the temperature rises to 850

°C, thus forming CN@HDS around the FeNP.

High-resolution TEM imaging indicates that the CN@HDS are different qualitatively to other known forms of carbon nanoparticles, such as fullerenes, carbon onions, carbon black or nano-horns, showing clearly the overall hemispherical morphology of the half dome structures. We have observed that with small iron nanoparticles the CN@HDS present a single layer, conversely, when the iron particles up to 20 nm diameter the half dome multilayers structures could be observed surrounding the metal core (

Figure 1b and

Figure S14). It was interesting to see that during the particle migration and coalescence of the FeNPs the capping agent still remained attached to the NPs as the solely available source of carbon in our systems is the organic base, as we have grown those CN@HDS on FLBN (BN was heated in air to removed advantageous carbon). The small Fe clusters during their migration were momentarily trapped at the step edges of the FLBN which acts as anchoring point, reaction site, and source of nitrogen atom which were uptake during the combustion that allowed the formation of the half dome structure 1 : 1 ratio (

Figure 5, Video file 2). Conversely, for the big nanoparticles in which the particle migration was not shown post intense heating the carbon nitride was surrounding the nanoparticle (

Figure S14).

The EELS of the half dome structures shows a weak peak at 284,5 eV which lies in the region of carbon chains and its low intensity is due to the presence of sp

1 CN.

15,23,36-37 In addition, the K-edge at 292 eV lies in the region of graphitic carbon, differing from diamond at 290 eV and amorphous carbon at 295 eV (

Figure 3b–

Figure 4d and

Figure S6).

36-37 The weakness of the σ* peak is due to the presence of nitrogen.

36 The broadness of the carbon K-edge above 292 eV (

Figure 3b,

Figure 4b and

Figure S6) is unusual for pure sp

2-hybridised carbon and is comparable to that observed for materials containing sp

1 and or sp

2 carbon and carbon nitride.

36-37 The high energy EELS measurements suggest that the bonding state within the carbon matrices does not match with well-known forms of carbon, but can be explained by the presence of sp

1-hybridised CN intermixed within sp

2-CN material.

15,31,32,35-38

In addition, the Raman of half dome (

Figure S8) data shows a peak at 2200 cm

-1 characteristic of CN sp

1 (

Figure S8).

23,39 Generally, Raman spectra of carbon nitride material show a characteristic peak between 2100 and 2200 cm

-1.

9,15,20,23,39 The vibration frequencies of solid carbon nitrides are expected to lie close to the modes of the analogous unsaturated CN molecules, which are 1500–1600 cm

-1 for chain like molecules and 1300–1600 cm

-1 for ring like molecules.

40-41 This means that there is little distinction in the G-D region between modes due to C or N atoms. For example, the frequency of bond stretching skeletal and ring modes is very similar in benzene, pyridine, and pyrrole, so it is difficult to assess the presence of N in an aromatic ring. The modes in amorphous carbon nitrides are also delocalized over both carbon and nitrogen sites because of nitrogen’s tendency to promote more clustered sp

2 bonding. It is expected little difference between the Raman spectra of nitrogenised and N-free carbon films in the 1000-2000 cm

-1 region. It was found no shift in the Raman spectra of two sputtered CN samples, one with 26 % at

14N and the other with the same content of

15N. On the other hand, we clearly have detected a direct contribution of CN sp

1 bonds in the 2100-2200 cm

-1 regions.

15,23,39

In a previous study, silver nanoparticles containing C

12H

25S were heated in a dedicated heating stage and post their intense heating it was shown that the sulfur contained in the organic capping agent was retained in the discorded carbon structure formed.

42 We have also heated the Fe

2O

3 capped with N(CH

3)

4OH in a dedicated heating stage, post intense heating, we have also shown for the first time that nitrogen of the N(CH

3)

4OH originally forming the capping agent can be retained in our CN@HDS (

Figures S4 and S9).

The EELS and Raman measurements shows the presence of Nitrogen from the sp1 CN formed during the heating process of the capping agent, the N(CH3)4OH due to intense heating transforms to nitrile N(CH)3 and CH3OH (E2 Reaction), the alcohol evaporate and the nitrile begin its transformation forming cyano groups that reacts with unsaturated carbon atoms to form cyanopolyynes chains. The cyano radicals can react with a variety of molecules in combustion chemistry, amongst which are simple unsaturated hydrocarbons.43-46

The synthesis of monocyanopolyyens and dicyanopolyynes could be easily produced either by laser ablation or with arch discharge techniques.15,47-48 For instance; two graphite electrodes were connected at the pole of the d.c. power supply and submerged in a Pyrex three-necked round bottom flask filled with acetonitrile to yield cyanopolyyens.15 In recent years, a renewed interest in the reaction of CN radicals with simple unsaturated hydrocarbons has risen because of their alleged role in some extra-terrestrial environments, namely the atmosphere of Saturn’s moon Titan and in cold molecular clouds in the interstellar medium (ISM).15 In addition cyanopolyyne have been extensively identified in cold molecular clouds and outflow of late M-type AGB carbon stars and their production routes have been widely investigated. The interstellar medium products can be arranged in four groups cyanopolyynes, methyl substituted cyanopolyynes, cyanopolyynes radicals and olefin nitriles containing a double carbon bond and a CN group.15

In a previous study, A. La Torre

et al has reported on the growth and formation of single boron nitride half dome structure BN@HDS mediated by small naked metal particle that reacted with the dangling bonds of the FLBN to form BN protrusion which display sharp corner and edges, the shape of the iron nanoparticle rearranged to a rectangular shape to promote the formation of BN@HDS (

Figure 4c, S13). The formation mechanism was already presented; two mechanisms can be accepted. One possibility is the dissolution-precipitation mechanism, whereby BN dissociates on the surface of the Fe clusters (noting B and N atoms are soluble in Fe)

29–31, followed by dissolution, diffusion and precipitation of BN in a form of dome-shaped nanostructures in advance of loss of the Fe at elevated temperature. This is similar to the case of carbon nanostructures, where the nucleation of protrusions on the surfaces of metal atom clusters can occur.

29 The second possibility is the "scooter" mechanism, as proposed to explain the growth of carbon nanotubes.

29 Here, mobile Fe atoms could continue to etch the BN layers in such a way that small strips remain that subsequently curl and close to form dome-shaped nanostructures. After nanostructure closure, the Fe atoms may either remain trapped inside the cage or escape, depending on the heating conditions or on the experimental conditions.

29

This new CN@HDS discovered in our study, might combines the features of graphene and carbyne as they can also be grown on graphene, and offers significant potential for a wide variety of applications. These CN@HDS are found to be very stable under ambient conditions in air or at high temperature in vacuum, exhibiting no measurable structural deterioration in our experiments, and thus being as robust as graphene and or diamond. Recently, we have reported on a new form of nanoscale carbon in the shape of hemispherical matrices with the bonding characteristics of either sp1 or sp2 carbon.49 The carbon matrices were formed spontaneously at high temperature from organic molecules adsorbed on the surface of silver nanoparticles, with the metal core acting simultaneously as catalyst and template for the carbon matrices growth. Significantly, this new form of carbon exhibits photo luminescent activity in the visible and near-IR ranges, with the wavelength of emitted light determined by the length of sp1 chains which link sp2 domains.49 The optical and electron properties of carbon chains and Nano ribbons are well known, the optical properties of sp2 carbon nitride has already been reported in literature showing an upper limit at c.a. 680 nm,23 hence, we speculate that the half dome structure could potentially present interesting photoluminescence properties ranging from the NIR range to the UV depending on the cyanopolyyne chain length.23,49

Last but not least, we should be taking into consideration the formation of a ternary domain by exploring the heating rate condition of Fe2O3@FLBN hybrid structure as the Iron particle is able to solubilise carbon, boron and nitrogen, hence it would also be possible to form pentagonal BCN monolayers or even BN chains as it was also reported by Cretu et al.,21 perhaps linear chains of BCN would be a possibility in the near future.

Experimental Methods

The TEM data sets were acquired using a JEOL 2100F (point resolution 0.19 nm; accelerating voltage 200 kV) with aberration-corrected probe and Gatan imaging filter (GIF) for electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) at the Institut de Physique et Chimie des Matériaux de Strasbourg, France; and a JEOL 2100F (point resolution 0.19 nm; accelerating voltage 200 kV) equipped with a Gatan Tridiem imaging filter for EELS at the Nanoscale and Microscale Research Centre, University of Nottingham, U.K. A Gatan 652 double-tilt heating holder was used for the in situ TEM heating experiments. The SEM data sets were acquired using an FEI Quanta 200 3D at an accelerating voltage of 5-10 kV and working distance of 15 mm, using secondary imaging mode, at the Nanoscale and Microscale Research Centre in Nottingham; and a Jeol 6700F at the Institut de Physique et Chimie des Matériaux de Strasbourg.

Nanoparticles of iron oxide were produced using the following standard procedure. 10 mL of 1 M FeCl

3 solution was mixed with 2.5 mL of 2 M FeCl

2 solution in a flask. The mixture was heated to 70

◦C under Ar, with mechanical stirring, and then 21 mL of 25% N(CH

3)

4OH aqueous solution was drop wise cast into the mixture. The resulting Fe

2O

3 nanoparticles (

Figure S4), with associated particle size histogram measured by SEM were isolated using a permanent magnet, allowing the supernatant to be decanted. Degassed water was then added to wash the precipitates. This procedure was repeated four times to remove excess ions and the tetramethylammonium salt from the suspension. The remaining precipitate was freezing dried to create a powder.

TEM supports were prepared by drop-casting a commercially available methanolic suspension of FLBN (Graphene Supermarket; lateral size of 50-200 nm and thickness of 1-5 monolayers) onto a gold mesh TEM grid and heating in air at 550◦C in a tube furnace to remove adventitious carbon. The Fe2O3 NP were suspended in methanol and dropped on to the BN flake / gold mesh grids. The Fe2O3/FLBN were heated in a dedicated heating stage holder in a TEM in situ.

TEM grids were prepared by drop casting a commercially available methanolic suspension of few layers graphene (Graphene supermarket). The Fe2O3NP were suspended in methanol and dropped on to the FLG flake / gold mesh grids. The TEM support containing FLG and Fe2O3 were heated in a dedicated heating stage holder in a TEM in situ.

Raman spectra were recorded using a Horiba–Jobin–YvonLabRAM Raman microscope, with a laser wavelength of 633 nm operating at low power (ca. 4 mW) and a 600-lines/mm grating. The detector was a Synapse CCD detector. Spectra were collected by recording 64 acquisitions of 5 s duration for each spectral window. Three spectra were recorded for each sample in order to account for sample in homogeneity. The Raman shift was calibrated using the Raleigh peak and the 520.7 cm-1 silicon line from a Si (100) reference sample.