1. Introduction

Disease progression and tumor recurrence in glioblastoma are unavoidable and contribute to its dismal prognosis. In approximately half of glioblastoma patients, progression and recurrence already occur during the course of treatment [

1,

2]. Standard treatment in glioblastoma consists of maximal safe neurosurgical resection, followed by 30 daily fractions of two Gy radiotherapy to a total of 60 Gy with concomitant chemotherapy and subsequently six 28 day-cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide, the so-called Stupp regimen [

1]. Regular radiological follow-up is performed for treatment response assessment and timely detection of tumor progression, and is essential for clinical decision making about continuation or discontinuation of treatment.

Multisequence magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for radiological follow-up and is regularly acquired during the different phases of standard treatment and thereafter [

3,

4]. Reliable assessment of radiological follow-up, however, is limited by the occurrence of treatment effects mimicking tumor progression, such as pseudoprogression [

5,

8]. Therefore, decisions about discontinuation of treatment are often postponed in asymptomatic patients with a new or increased contrast enhancing lesion on follow-up MRI less than three months after the end of radiotherapy [

9]. Advanced sequences such as perfusion MRI are increasingly employed in clinical practice as they contribute to a better differentiation between tumor progression and treatment effects [

6].

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal interval for radiological follow-up during treatment [

10]. The interval of scheduled MRI follow-up therefore differs between centers and countries. However, most centers perform MRI at the end of the concomitant chemoradiation phase and after every two to three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy [

2,

4,

10]. It is unknown if this pragmatic strategy actually benefits the patient and how it influences clinical decision making about continuation or discontinuation of treatment. Moreover, it is uncertain how much perfusion MRI contributes to clinical decision making when suspected progression occurs during treatment.

The aims of this study were (1) to assess the consequences of scheduled and unscheduled follow-up scans on treatment decisions during standard concomitant and adjuvant treatment in patients with glioblastoma. Since treatment decisions are often postponed due to the occurrence of treatment effects, we hypothesized that the impact of the scheduled scans during treatment is relatively low, and thus question whether all scheduled scans are necessary. In addition, (2) we evaluated how often follow-up scans resulted in diagnostic uncertainty, such as the inability of differentiating tumor progression from pseudoprogression, and (3) whether application of perfusion MRI improved clinical decision making and led to less diagnostic uncertainty.

2. Materials and Methods

Adult patients with a histopathologically confirmed glioblastoma, who received standard treatment according to the Stupp protocol [

1] between 2004 and 2019 at our tertiary university hospital, were retrospectively included if they underwent at least one follow-up MRI during treatment. Exclusion criteria were other intracranial lesions, previous radiotherapy to the brain and a history of previous neurosurgery other than for the glioblastoma. Patients receiving other chemotherapy regimens than temozolomide were also excluded. This retrospective cohort study was approved by the local ethics committee and the need for written informed was waived. None of the included patients objected against the use of their anonymized data for research purposes.

2.1. Data extraction

Clinical data were extracted from the electronic patient records. Patients underwent maximal safe neurosurgical resection or biopsy to confirm diagnosis. Resected or biopsied tissue was evaluated by a neuropathologist and, in more recent years, molecular markers were determined, including methylation of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyl-transferase (MGMT) gene and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status.

Scan data consisted of scheduled follow-up scans and unscheduled scans. Scheduled follow-up scans were acquired at four standard timepoints: (1) < 72 hours post-operatively (post-OP); (2) four weeks after completion of concomitant chemoradiotherapy (post-CCRT); (3) after three of six cycles adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy (TMZ3/6); and (4) after completion of six cycles of adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy (TMZ6/6). Unscheduled scans were divided into two categories: (I) scans that were acquired due to new or worsened clinical symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting or neurological deficits; and (II) extra scans due to uncertainty on the previous (scheduled) scan.

For each scan its consequence on the ongoing treatment was assessed. Decisions from the multidisciplinary tumor board meetings were assessed. Treatment consequences were treated as categorized variables and divided into three groups: (a) no treatment consequences, thus treatment was continued as scheduled; (b) minor consequences, which were defined as treatment adjustments without influencing the Stupp protocol, such as initiating or changing dosage of corticosteroids or anti-epileptics, but continuing adjuvant chemotherapy; and (c) major treatment consequences that led to interruption or early termination of the Stupp protocol, second line chemotherapy including experimental regimens, or neurosurgical re-resection. In addition to the treatment consequences, it was assessed if the scan led to diagnostic uncertainty, meaning it was unclear whether the imaging changes were due to tumor progression or treatment effects (pseudoprogression). The post-OP scans were left out for this analysis.

2.2. MRI acquisition

MRI images were acquired on either a 1.5T or a 3.0T scanner. Various imaging protocols were followed, which always included anatomical sequences (pre- and post-contrast T1, T2 and fluid attenuated inversion-recovery [FLAIR]) with diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) or diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and with or without perfusion weighted imaging (PWI). For the anatomical sequences a pre- and post-contrast 3D T1 weighted MPRage (Repetition time [TR] 2100-2300 ms, echo time [TE] 2.32-2.67 ms, inversion time [TI] 900 ms, flip angle 8 degrees, slice thickness 1 mm, voxel size 1.0x1.0x1.0 mm3), a transverse T2-weighted turbo spin echo (TSE) sequence (TR 4630-8800 ms, TE 92-100 ms, flip angle 150 degrees, slice thickness 3-5 mm, voxel size 0.4x0.4x3.0-5.0 mm3), and a 3D (FLAIR) (TR 5000 ms, TE 337-391 ms, TI 1800 ms, slice thickness 1 mm, voxel size 1.0x1.0x1.0 mm3) were acquired. For DWI a transverse RESOLVE sequence was acquired (TR 4440 ms, TE 60-104 ms, flip angle 180 degrees, slice thickness 4 mm, voxel size 1.1x1.1x4.0 mm3) with two b-values of 0 and 1000 s/mm2. In cases were DTI was used instead of DWI, a transverse DTI was acquired with an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR 5300 ms, TE 93 ms, slice thickness 5 mm, voxel size 0.7x0.7x5.0 mm3) with 12 diffusion directions using b-values of 0 and 1000 s/mm2. For PWI a transverse dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence was used (TR 1780 ms, TE 30 ms, flip angle 90 degrees, slice thickness 4 mm, voxel size 0.9x0.9x4.0 mm3) which was acquired during administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent (Dotarem) at an infusion rate of 4 mL/s. A pre-bolus of ¼ dose was used before acquisition of PWI.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed in SPSS version 23.0. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess differences between categorical variables. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) was used since there were repeated measurements and to account for missing and clustered data. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was used throughout this study.

3. Results

There were 261 patients included in this study with a median age of 59 years and of whom 164 (62.8%) were men. A majority of 151 patients (57.9%) completed standard treatment, whilst in the remaining 110 patients (42.1%) treatment was terminated early. Median survival was 15 months.

Table 1 provides an overview of the general characteristics of the patients included.

3.1. Treatment consequences

There were 790 scheduled scans acquired (

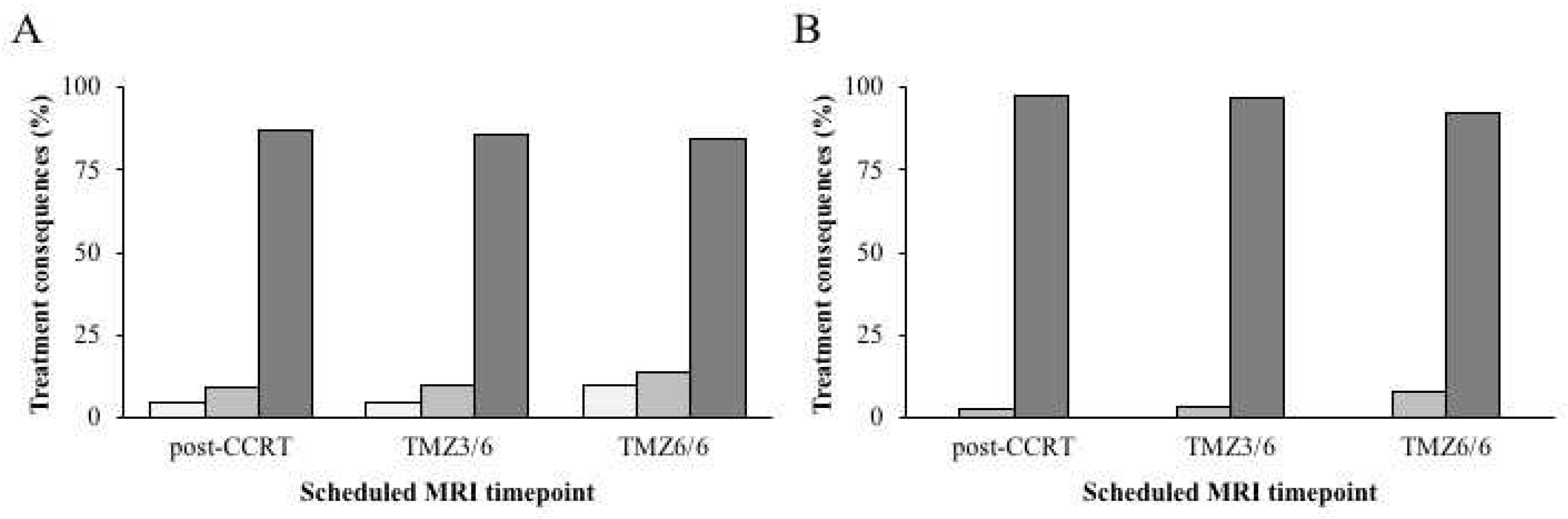

Table 2); (1) post-OP in 188 patients (72%), (2) post-CCRT in 258 patients (98.9%), (3) TMZ3/6 in 190 patients (72.8%), and (4) TMZ6/6 in 154 patients (59%). For the post-OP timepoint, none of the 188 scans had any treatment consequences. This was also the case for 224 (86.8%) post-CCRT scans, 163 (85.8%) TMZ3/6 scans and 130 (84.4%) TMZ6/6 scans. Minor treatment consequences occurred after 11 (4.3%) post-CCRT scans, eight (4.2%) TMZ3/6 scans and three (1.9%) TMZ6/6 scans. There were 23 (8.9%), 19 (10%), and 21 (13.6%) major treatment consequences after the post-CCRT, TMZ3/6 and TMZ6/6 scans, respectively (

Figure 1A). In the majority of these cases, other variables such as clinical symptoms or a poor clinical condition of the patient also contributed to the treatment decision of the multidisciplinary tumor board. When regarding the cases in which the decision was based on the MRI alone, major consequences occurred in six patients (2.3%) after the post-CCRT scan, six patients (3.2%) after the TMZ3/6 scan, and 12 patients (7.8%) after the TMZ6/6 scan (

Figure 1B).

Among the included patients, 56 unscheduled scans were performed during treatment. Unscheduled scans were most commonly acquired during the adjuvant chemotherapy phase with a minority being acquired during the concomitant chemoradiotherapy. The reasons for these unscheduled scans were (I) new or worsened clinical symptoms in 25 cases (44.6%) and (II) uncertainty on the previous (scheduled) scan in 31 cases (55.4%). In the 25 cases of new or worsened clinical symptoms, 15 scans (60%) did not lead to any treatment consequences. Two scans (8%) had minor consequences and eight scans (32%) led to major consequences. For the 31 scans that were acquired due to uncertainty on the previous MRI, 21 scans (67.8%) had no consequences, whilst one (3.2%) and nine (29%) scans resulted in minor and major treatment consequences, respectively.

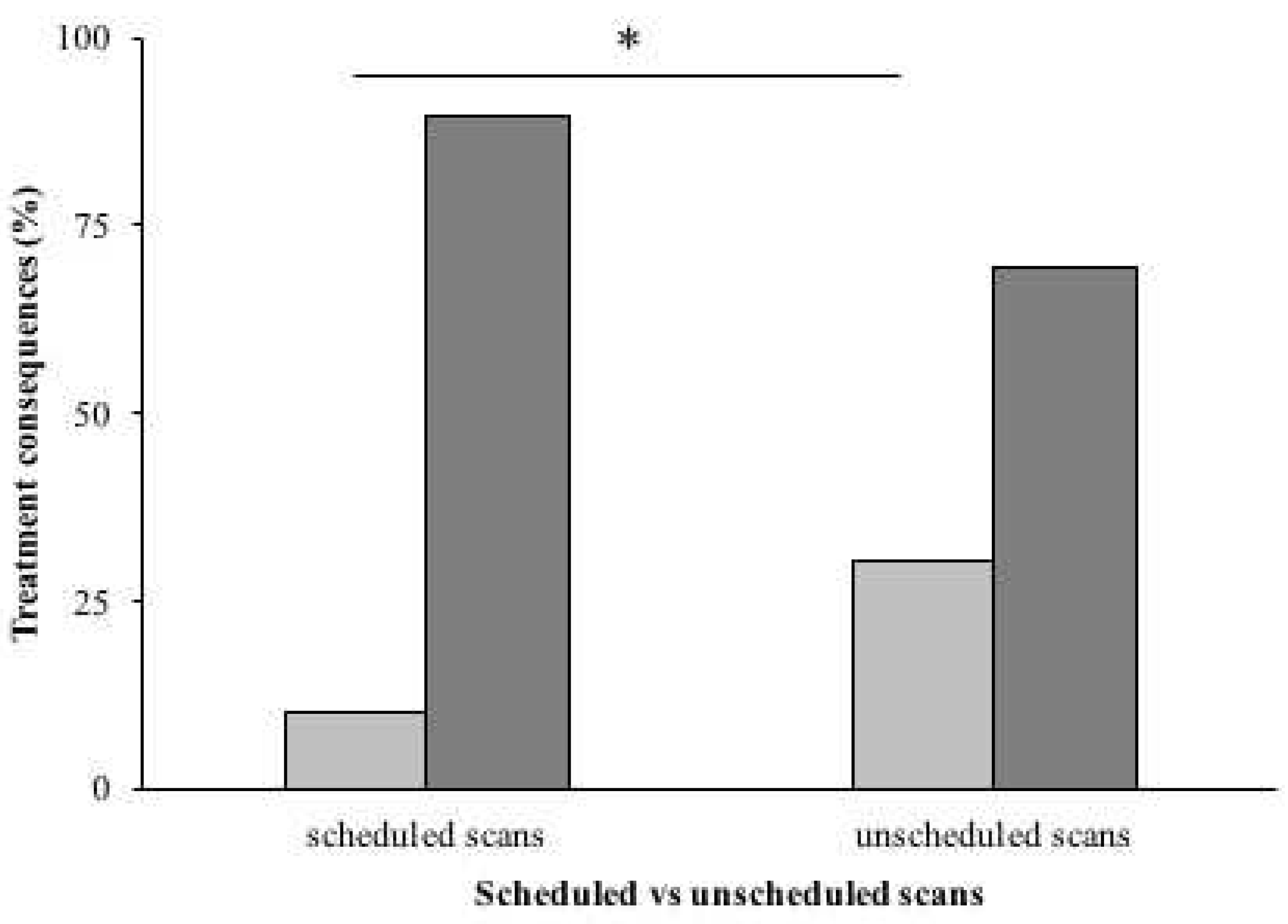

Comparing the scheduled scans (post-CCRT, TMZ3/6 and TMZ6/6) and unscheduled scans, major treatment consequences occurred after 62/602 (10.5%) scheduled scans and after 17/56 (30.4%) unscheduled scans (

Figure 2). This difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

3.2. Diagnostic uncertainty on MRI

During the course of standard treatment, new contrast enhancement or a significant increase of an already present contrast enhancing lesion was seen in 175 patients (67%). For the 602 scheduled scans, 167 (27.7%) resulted in diagnostic uncertainty about the effects of treatment. Diagnostic uncertainty occurred in 11 of the 56 (19.6%) unscheduled scans. There was no statistical difference between scheduled and unscheduled scans (p=0.192). For the post-CCRT, TMZ3/6, and TMZ6/6 timepoints, 88 (34.1%), 55 (28.9%), and 24 (15.6%) scans caused diagnostic uncertainty, respectively. The post-CCRT (p=0.003) and TMZ3/6 (p<0.001) timepoints both differed significantly from the TMZ6/6 timepoint. There was no significant difference between the post-CCRT and TMZ3/6 timepoints (p=0.247). For the unscheduled scans, three (12%) of the scans acquired due to new or worsened clinical symptoms resulted in diagnostic uncertainty, whilst this was the case for eight (25.8%) scans that were acquired due to uncertainty on the previous MRI (p=0.321). Eventually it was established by multidisciplinary decision in the tumor board, that the new or increased contrast enhancement was due to true tumor progression in 74 patients (42.3%) and pseudoprogression in 48 patients (27.4%) based on the RANO criteria.9 For the remaining 53 patients (30%) it was not established whether the imaging changes were due to tumor progression or treatment effects by the end of standard adjuvant treatment.

3.3. Perfusion weighted imaging

Perfusion weighted imaging was acquired in 56% of the scheduled follow-up MRI scans (post-CCRT, TMZ3/6 and TMZ6/6). Inclusion of a perfusion sequence in the imaging protocol did not result in more major treatment consequences compared to protocols without perfusion imaging (p=0.871). However, there was less diagnostic uncertainty following scheduled scans that incorporated a perfusion sequence (56%) compared to scheduled scans without perfusion imaging (44%) (p=0.021).

4. Discussion

This retrospective longitudinal study demonstrated that approximately 90% of the scheduled follow-up scans during standard concomitant and adjuvant treatment in 261 glioblastoma patients did not result in any treatment consequences, whilst diagnostic uncertainty was caused by about a quarter of all acquired scans. Furthermore, unscheduled scans led to significantly more treatment consequences than the scheduled scans. The incorporation of perfusion MRI in the imaging protocol resulted in less diagnostic uncertainty without impact on the treatment. Our results do not support the current radiological follow-up schemes during standard treatment in glioblastoma patients, and suggest that at least one of the scheduled scans could potentially be omitted.

The current practice of scheduled MRI follow-up with predetermined intervals during standard treatment and scheduled routine surveillance after completion of standard treatment, is not evidence-based [

10]. A previous study by Monroe et al investigated how often tumor progression was discovered on scheduled follow-up scans versus unscheduled scans due to the development of symptoms [

4]. The authors found that 63.5% of the patients with tumor progression were detected with scheduled surveillance imaging [

4]. However, half of the patients in the surveillance detection group were also experiencing symptoms at time of the scheduled scan [

4]. Another recent study aimed to establish the optimal follow-up interval of glioblastoma patients by using parametric modeling of standardized progression-free survival curves [

2]. An interval of 7-8 weeks between scans for at least two years was found to be optimal [

2]. However, this study only investigated the period after completion of standard treatment, whereas our study focused on the radiological follow-up during concomitant and adjuvant treatment. A large survey among all neuro-oncology centers in the United Kingdom demonstrated that a lot of variation exists in predefined scan timepoints between centers [

11]. Most centers (>70%) performed standard MRI follow-up early post-operative, during adjuvant treatment and after completion of standard adjuvant treatment, comparable to the scheme used in our hospital [

11]. Currently a large multicenter retrospective cohort study is undertaken (INTERVAL-GB) to assess MRI monitoring practice during and after standard treatment in the United Kingdom and Ireland and how this influences survival [

12].

Our study showed that only a low number (8.9-13.6%) of scheduled follow-up MRI scans at predetermined intervals led to major treatment consequences, whilst diagnostic uncertainty often occurred. Additionally, the incidence of early treatment termination was even lower when decisions about treatment continuation or discontinuation were made based on the radiological information alone (2.3-7.8%). Furthermore, unscheduled scans in symptomatic patients more often led to major treatment consequences than these predetermined scheduled scans in asymptomatic patients. This further emphasizes the problem about the current pragmatic approach and raises the question whether one or more of these scheduled follow-up MRI scans during standard concomitant and adjuvant treatment could potentially be omitted.

Certain timepoints could still have clinical value despite a low number of major treatment consequences, however. None of the post-OP scans in our cohort led to any treatment consequences. This is in line with a previous study that demonstrated no difference in the number of patients that received chemoradiation therapy between glioblastoma patients with and without a postoperative scan [

13]. The same study showed that use of postoperative MRI did not result in a survival benefit for patients [

13]. However, postoperative MRI is important in determining the extent of resection, which is an established important prognostic factor in glioblastoma [14-16]. Additionally, postoperative MRI can reveal possible surgical complications and is used as reference image to interpret subsequent MRI scans. The post-CCRT timepoint serves as a baseline scan after radiotherapy and also visualizes potential radiotherapy related adverse effects [

17,

18]. The TMZ6/6 timepoint marks the end of standard adjuvant treatment and can thus be used as a baseline scan for experimental secondline therapeutic regimens. The TMZ6/6 scan also had the highest number of major treatment consequences. The TMZ3/6 scan, however, lacks a pragmatic rational such as the post-OP or post-CCRT timepoints.

Treatment induced changes such as pseudoprogression causing diagnostic uncertainty occur frequently during treatment in glioblastoma patients [

19]. For our cohort, diagnostic uncertainty occurred in 27.7% of scheduled follow-up scans, which is comparable to the literature [

19]. Scheduled scans early in the treatment scheme, such as the post-CCRT and TMZ3/6, resulted in more diagnostic uncertainty than the TMZ6/6 scan at the end of standard treatment. It is known that diagnostic uncertainty can induce patient and caregiver anxiety [20-22]. Several studies among cancer patients have evaluated follow-up scan associated distress, sometimes referred to as “scanxiety”, and found a negative impact on quality of life [23-25]. Furthermore, for glioblastoma patients specifically, the quality of life was found to be lowest during adjuvant therapy [

26]. If the TMZ3/6 scan were to be omitted, this would result in 29% less diagnostic uncertainty based on our results. This would mean 55 of the 190 patients from our cohort scanned at this timepoint would not be in doubt about the nature of new suspicious lesion on MRI. However, a “negative” MRI scan demonstrating no signs of radiological progression could also be reassuring and reduce anxiety and distress [

27]. Currently, there is no data available on the influence of diagnostic uncertainty versus reassurance in glioblastoma patients during treatment and future studies on this topic are warranted.

Perfusion MRI is becoming increasingly important in radiological follow-up protocols for glioblastoma, as perfusion MRI has a high diagnostic accuracy for differentiating tumor progression from treatment effects [

6,

28,

29]. Indeed, use of perfusion MRI led to less diagnostic uncertainty on follow-up scans in our cohort. However, perfusion MRI did not influence the consequences of the scan on treatment decisions. A possible explanation is that perfusion MRI has only become standard of care in recent years, and clinical experience and quantification of this technique have expanded since [

30]. Another explanation could be that although perfusion has a high diagnostic accuracy of >85% [

6], it is not 100%. Clinicians frequently give patients the benefit of the doubt and continue treatment as standard second line treatment is not available.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, its retrospective nature which may have resulted in sampling bias, since perfusion MRI and genetic biomarkers only became standard of care in recent years. The number of patients for whom IDH mutation and MGMT methylation status are known are hence relatively low. Secondly, the number of patients who were scanned on 3.0T MRI scanners was too low to allow for subanalysis. It is however unlikely that these mutations or differences in field strength would impact the results. Furthermore, this is a single center study and may not be fully applicable to other centers or countries. A multicenter study is currently ongoing and it will be interesting to see if results are in line with our conclusions [

12]. Finally, the end point of this study was the completion of standard treatment, the subsequent follow-up period of active surveillance was therefore not analyzed.

5. Conclusions

Scheduled follow-up scans during standard treatment in glioblastoma patients rarely have major treatment consequences such as early termination of treatment, but do introduce considerable diagnostic uncertainty. The use of perfusion MRI does not impact treatment decision making, but significantly reduces diagnostic uncertainty. This study does not support the current pragmatic approach with standard scheduled follow-up MRI. Potentially one or more scheduled MRI scans could be omitted or replaced by unscheduled scans in symptomatic patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; methodology, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; software, B.D., A.D., and A.H.; validation, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; formal analysis, B.D., A.D., R.E., and A.H.; investigation, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; resources, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; data curation, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; writing—review and editing, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; visualization, B.D., A.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; supervision, B.D., R.E., P.L., H.J., R.D., and A.H.; project administration, B.D., A.D., R.E., and A.H.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji SY, Lee J, Lee JH, et al. Radiological assessment schedule for high-grade glioma patients during the surveillance period using parametric modeling. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 837–847. [CrossRef]

- Lundy, P.; Domino, J.; Ryken, T.; Fouke, S.; McCracken, D.J.; Ormond, D.R.; Olson, J.J. The role of imaging for the management of newly diagnosed glioblastoma in adults: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline update. J. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 150, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe CL, Travers S, Woldu HG, Litofsky NS. Does Surveillance-Detected Disease Progression Yield Superior Patient Outcomes in High-Grade Glioma? World Neurosurg. 2020, 135, e410–e417. [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, D.; Stalpers, L.; Taal, W.; Sminia, P.; van den Bent, M.J. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijken BRJ, van Laar PJ, Holtman GA, van der Hoorn A. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging techniques for treatment response evaluation in patients with high-grade glioma, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2017, 27, 4129–4144. [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Chung, C.; Pope, W.B.; Boxerman, J.L.; Kaufmann, T.J. Pseudoprogression, radionecrosis, inflammation or true tumor progression? challenges associated with glioblastoma response assessment in an evolving therapeutic landscape. J. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 134, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fèvre, C.; Constans, J.-M.; Chambrelant, I.; Antoni, D.; Bund, C.; Leroy-Freschini, B.; Schott, R.; Cebula, H.; Noël, G. Pseudoprogression versus true progression in glioblastoma patients: A multiapproach literature review. Part 2 – Radiological features and metric markers. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2021, 159, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; Macdonald, D.R.; Reardon, D.A.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Sorensen, A.G.; Galanis, E.; DeGroot, J.; Wick, W.; Gilbert, M.R.; Lassman, A.B.; et al. Updated Response Assessment Criteria for High-Grade Gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1963–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.; A Lawrie, T.; Kernohan, A.; Jenkinson, M.D. Interval brain imaging for adults with cerebral glioma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 12, CD013137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, T.C.; Luis, A.; Brazil, L.; Thompson, G.; Daniel, R.A.; Shuaib, H.; Ashkan, K.; Pandey, A. Glioblastoma post-operative imaging in neuro-oncology: current UK practice (GIN CUP study). Eur. Radiol. 2020, 31, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie CS, Bligh ER, Poon MTC Neurology and Neurosurgery Interest Group (NANSIG), et al. Imaging timing after glioblastoma surgery (INTERVAL-GB): protocol for a UK and Ireland, multicentre retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063043. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowczynski, O.D.; Zammar, S.; Bourcier, A.J.; Langan, S.T.; Liao, J.; Specht, C.S.; Rizk, E.B. Utility of Early Postoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging After Glioblastoma Resection: Implications on Patient Survival. World Neurosurg. 2018, 120, e1171–e1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanai, N.; Polley, M.-Y.; McDermott, M.W.; Parsa, A.T.; Berger, M.S. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaichana, K.L.; Jusue-Torres, I.; Navarro-Ramirez, R.; Raza, S.M.; Pascual-Gallego, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Hernandez-Hermann, M.; Gomez, L.; Ye, X.; Weingart, J.D.; et al. Establishing percent resection and residual volume thresholds affecting survival and recurrence for patients with newly diagnosed intracranial glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2013, 16, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown TJ, Brennan MC, Li M, et al. Association of the Extent of Resection With Survival in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1460–1469. [CrossRef]

- Prust, M.J.; Jafari-Khouzani, K.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Polaskova, P.; Batchelor, T.T.; Gerstner, E.R.; Dietrich, J. Standard chemoradiation for glioblastoma results in progressive brain volume loss. Neurology 2015, 85, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, J.; Platzek, I.; Hofheinz, F.; Mutsaerts, H.J.; Asllani, I.; van Osch, M.J.; Seidlitz, A.; Krukowski, P.; Gommlich, A.; Beuthien-Baumann, B.; et al. Photon vs. proton radiochemotherapy: Effects on brain tissue volume and perfusion. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 128, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.W.; Westerlaan, H.E.; Holtman, G.A.; Aden, K.M.; van Laar, P.J.; van der Hoorn, A. Incidence of Tumour Progression and Pseudoprogression in High-Grade Gliomas: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2017, 28, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Charlson, M.E.; Schenkein, E.; Wells, M.T.; Furman, R.R.; Elstrom, R.; Ruan, J.; Martin, P.; Leonard, J.P. Surveillance CT scans are a source of anxiety and fear of recurrence in long-term lymphoma survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 2262–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, S.; Mehdorn, H.M. Fear of disease progression in adult ambulatory patients with brain cancer: prevalence and clinical correlates. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3521–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughan, A.R.; Lanoye, A.; Aslanzadeh, F.J.; Villanueva, A.A.L.; Boutte, R.; Husain, M.; Braun, S. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Death Anxiety: Unaddressed Concerns for Adult Neuro-oncology Patients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med Settings 2021, 28, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauml JM, Troxel A, Epperson CN, et al. Scan-Associated Distress in Lung Cancer: Quantifying the Impact of “Scanxiety”. Lung Cancer 2016, 100, 110–113. [CrossRef]

- Derry-Vick, H.M.; Heathcote, L.C.; Glesby, N.; Stribling, J.; Luebke, M.; Epstein, A.S.; Prigerson, H.G. Scanxiety among Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review to Guide Research and Interventions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.C.; Thompson, G.; Bulbeck, H.; Boele, F.; Buckley, C.; Cardoso, J.; Canas Dos Santos, L.; Jenkinson, D.; Ashkan, K.; Kreindler, J.; et al. A Position Statement on the Utility of Interval Imaging in Standard of Care Brain Tumour Management: Defining the Evidence Gap and Opportunities for Future Research. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 620070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonetti, A.; Puglisi, G.; Rossi, M.; Viganò, L.; Nibali, M.C.; Gay, L.; Sciortino, T.; Howells, H.; Fornia, L.; Riva, M.; et al. Factors Influencing Mood Disorders and Health Related Quality of Life in Adults With Glioma: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 662039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyldesley-Marshall N, Greenfield S, Neilson S, English M, Adamski J, Peet A. Qualitative study: patients’ and parents’ views on brain tumour MRIs. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2020, 105, 166–172.

- Van Dijken BRJ, van Laar PJ, Smits M, et al. Perfusion MRI in treatment evaluation of glioblastomas: Clinical relevance of current and future techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019, 49, 11–22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martucci, M.; Russo, R.; Giordano, C.; Schiarelli, C.; D’apolito, G.; Tuzza, L.; Lisi, F.; Ferrara, G.; Schimperna, F.; Vassalli, S.; et al. Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of Treated Glioblastoma: A Pictorial Essay. Cancers 2023, 15, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thust, S.C.; Heiland, S.; Falini, A.; Jäger, H.R.; Waldman, A.D.; Sundgren, P.C.; Godi, C.; Katsaros, V.K.; Ramos, A.; Bargallo, N.; et al. Glioma imaging in Europe: A survey of 220 centres and recommendations for best clinical practice. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 3306–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).