Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature review on financial access

1.2. Literature review on motivation

1.3. Background

1.3.1. Village Defense Party (VDP)

1.3.2 Bangladesh Bank’s initiatives for financial access

2. Materials and Methods

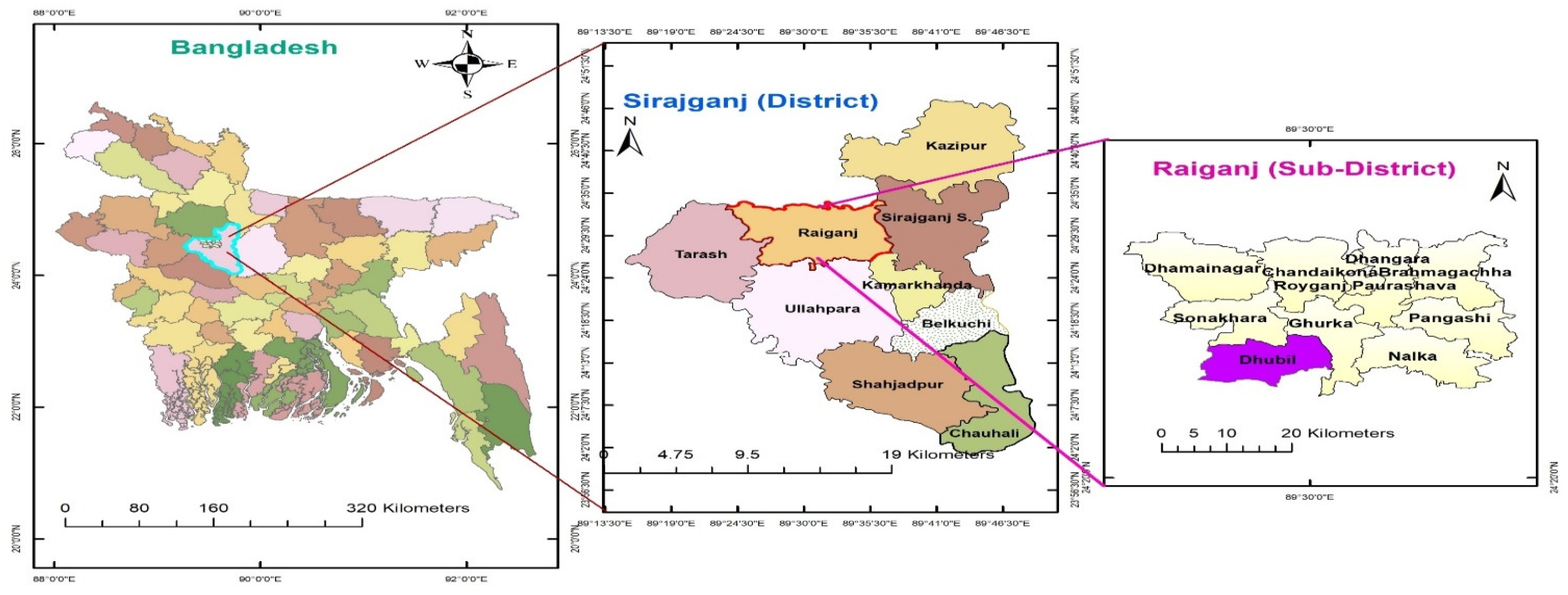

2.1. The study area

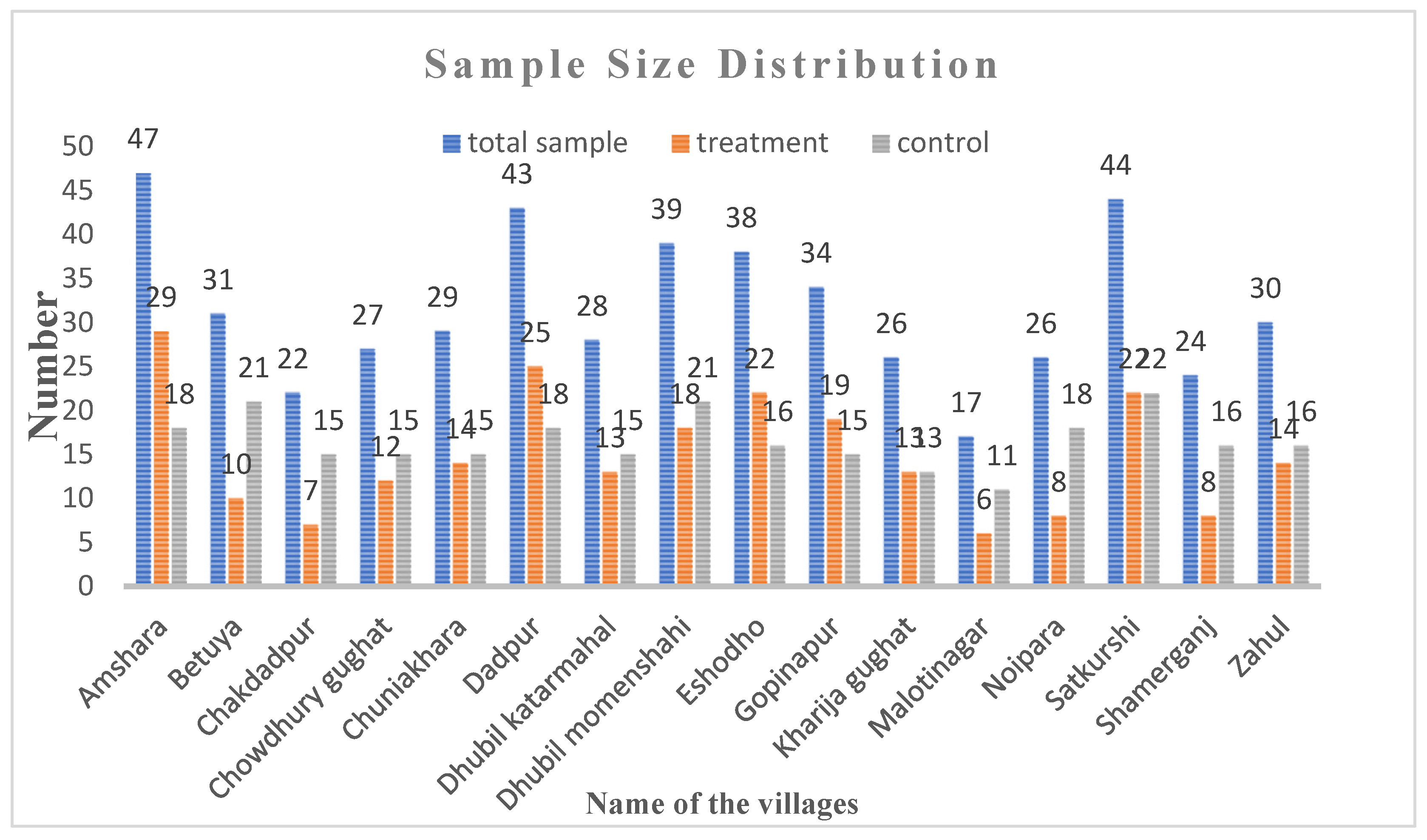

2.2. Sampling and data collection

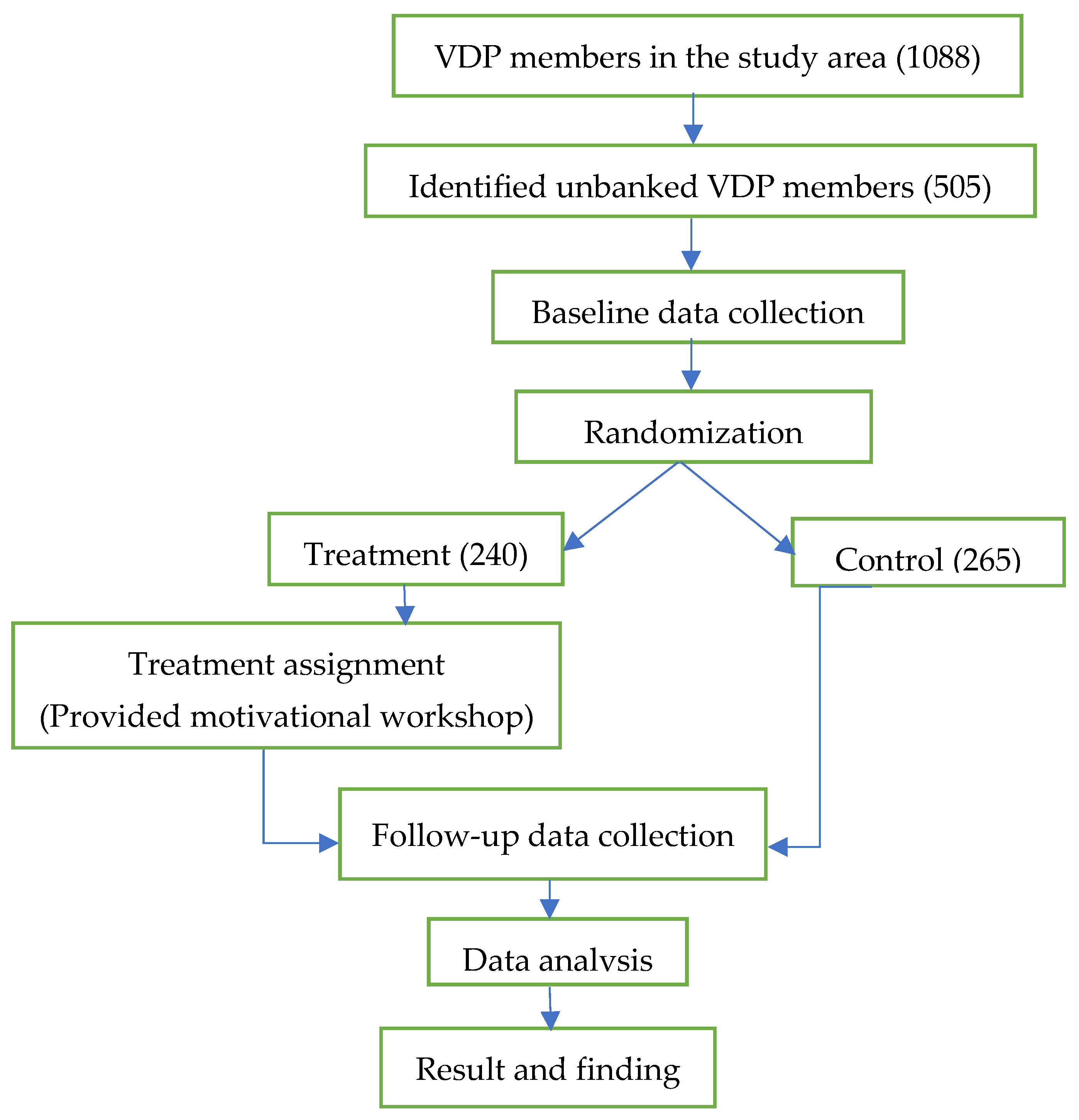

2.3 Research design

2.4. Treatment Assignment

2.5. Data Analysis approach

2.6. Summary statistics

2.7. Balance check

3. Results

3.1. Account opening take up rate

3.2. Average Treatment Effect (ATE)

3.3. Conditional average treatment effect on opening savings accounts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.3. Limitations of the study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Outcome | Coefficient and Std err | Coefficient and Std err |

|---|---|---|

| Total account opening | 2.22*** (.2838) | 1.23*** (.1455) |

| Bank account opening | 3.42*** (1.025) | 1.41*** (.3526) |

| MFIs account opening | 1.36*** (.4151) | .6426*** (.1879) |

| MFS account opening | 1.98*** (.3962) | .9753*** (.1804) |

| Regression | Logit | Probit |

| Observation | 505 | 505 |

| 1 | UFA overview 2020: Universal Financial Access by 2020. The World Bank, accessed on July 3, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/brief/achieving-universal-financial-access-by-2020

|

| 2 | Universal Financial Access, The country progress, The world Bank. Accessed on June 21, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://ufa.worldbank.org/en/country-progress

|

| 3 | Bangladesh: percent people with bank account. Accessed on June 21, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Bangladesh/percent_people_bank_accounts/

|

| 4 | According to the organogram of VDP, every village has 64 members. The study area has 17 villages. Thus, the total VDP in the study area is (17*64) =1088. |

| 5 | Bangladesh Ansar and VDP works under the ministry of Home Affairs consisting of ansar, battalion ansar and VDP members. |

| 6 | The embodiment rules of Village Defense Party members |

| 7 | The Village Defense Party Act- 1995 |

| 8 | Several examples of 3rd and 4th class job in Bangladesh are office assistance, night-guard, driver, computer operator, gardener, cook, cleaner. |

| 9 | Bangladesh Bank, Financial Inclusion Department. Accessed on May 15, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://finlit.bb.org.bd/

|

| 10 | Bangladesh Bank, the central bank of Bangladesh, Banks and financial institutions. Accessed on May 15, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://www.bb.org.bd/en/index.php/financialactivity/bankfi

|

| 11 | Bangladesh National Portal, Dhubil Union. Accessed on May 10, 2023. Data can be retrieved from: https://dhubilup.sirajganj.gov.bd/bn/site/page/KWlR-%E0%A6%8F%E0%A6%95%E0%A6%A8%E0%A6%9C%E0%A6%B0%E0%A7%87-%E0%A6%A7%E0%A7%81%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%BF%E0%A6%B2-%E0%A6%87%E0%A6%89%E0%A6%A8%E0%A6%BF%E0%A7%9F%E0%A6%A8

|

| 12 | Population and housing census 2011. National volume 2: Union Statistics. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. |

| 13 | Ten enumerators collected data from the villages according to the list provided by district office. Some enumerators covered more than two small villages for collecting data. |

References

- Abdul Razak, A.; Asutay, M. Financial Inclusion and Economic Well-Being: Evidence from Islamic Pawnbroking (Ar-Rahn) in Malaysia. Res Int Bus Finance 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, A.; Nagabhushana, C.; Sarkar, R.; Shah, R.; Singh, G. Financial Access and Women’s Role in Household Decisions: Empirical Evidence from India’s National Rural Livelihoods Project. J Dev Econ 2022, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y. Achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals through Financial Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review of Access to Finance across the Globe. International Review of Financial Analysis 2021, 77, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, Md.N.A. Does Financial Inclusion Promote Women Empowerment? Evidence from Bangladesh. Applied Economics and Finance 2017, 4, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.K.; Karmaker, S.C.; Hosan, S.; Chapman, A.J.; Uddin, M.K.; Saha, B.B. Energy Poverty Alleviation through Financial Inclusion: Role of Gender in Bangladesh. Energy 2023, 282, 128452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Tu, Y. Impact of Financial Inclusion on the Urban-Rural Income Gap—Based on the Spatial Panel Data Model. Financ Res Lett 2023, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, A.; Pino, G. Local Financial Access and Income Inequality in Chile. Econ Lett 2022, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.

- Dupas, P.; Karlan, D.; Robinson, J.; Ubfal, D. Banking the Unbanked? Evidence from Three Countries. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2018, 10, 257–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and Opportunities to Expand Access to and Use of Financial Services. World Bank Economic Review 2020, 34, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez Peria, M.S. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2016, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L. Measuring Financial Inclusion: The Global Findex Database; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank, 2012;

- Conroy, J. APEC AND FINANCIAL EXCLUSION: MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR COLLECTIVE ACTION?; 2005; Vol. 12.

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez Peria, M.S. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2016, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prina, S. Banking the Poor via Savings Accounts: Evidence from a Field Experiment. J Dev Econ 2015, 115, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.W.; Rogers, K.E.; Smith, R.C. High School Economic Education and Access to Financial Services. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2010, 44, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoofs, A. Promoting Financial Inclusion for Savings Groups: A Financial Education Programme in Rural Rwanda. J Behav Exp Finance 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Qi, S. Childhood Matters: Family Education and Financial Inclusion. Pacific Basin Finance Journal 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, C.; Toth, R.; Merdikawati, N. Can a Multipronged Strategy of “Soft” Interventions Surmount Structural Barriers for Financial Inclusion? Evidence From the Unbanked in Papua New Guinea. Journal of Development Studies 2022, 58, 2460–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Tran, D.; Goto, D.; Kawata, K. Does Experience Sharing Affect Farmers’ pro-Environmental Behavior? A Randomized Controlled Trial in Vietnam. World Dev 2020, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; De, S. How Much Does Having a Bank Account Help the Poor? Journal of Development Studies 2018, 54, 1551–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Sahu, T.N. Financial Inclusion in North-Eastern Region: An Investigation in the State of Assam. Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management 2022, 19, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Inclusion.

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez, M.S.; The, P.; Bank, W. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts; 2012;

- Chin, A.; Karkoviata, L.; Wilcox, N.; Autor, D.; Banerjee, A.; Craig, S.; Duflo, E.; Juhn, C. Impact of Bank Accounts on Migrant Savings and Remittances: Evidence from a Field Experiment *; 2010;

- Aguila, E.; Angrisani, M.; Blanco, L.R. Ownership of a Bank Account and Health of Older Hispanics. Econ Lett 2016, 144, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, K.; Roy, P.K.; Alam, S. The Impact of Banking Services on Poverty: Evidence from Sub-District Level for Bangladesh. J Asian Econ 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njanike, K. An Investigation on the Determinants of Opening a Bank Account in Zimbabwe. Dev South Afr 2019, 36, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayeth Hussain, A.H.M.; Endut, N.; Das, S.; Chowdhury, M.T.A.; Haque, N.; Sultana, S.; Ahmed, K.J. Does Financial Inclusion Increase Financial Resilience? Evidence from Bangladesh. Dev Pract 2019, 29, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Financial Inclusion Strategy.

- Corrado, G. Institutional Quality and Access to Financial Services: Evidence from European Transition Economies. Journal of Economic Studies 2020, 47, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Sahu, T.N. Bank Branch Outreach and Access to Banking Services toward Financial Inclusion: An Experimental Evidence. Rajagiri Management Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujeri, M.K. Improving Access of the Poor to Financial Services; 2015.

- Agarwal, S.; Pulak, S.A.; Soumya, G.; Ghosh, K.; Piskorski, T.; Seru, A.; Banerjee, A.; Beck, T.; Chomsisengphet, S.; Levine, R.; et al. Banking the Unbanked: What Do 255 Million New Bank Accounts Reveal about Financial Access?

- Sarma, M.; Pais, J. Financial Inclusion and Development. J Int Dev 2011, 23, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakara, A.A.; Osabuohien, E.S. Households’ ICT Access and Bank Patronage in West Africa: Empirical Insights from Burkina Faso and Ghana. Technol Soc 2019, 56, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efobi, U.; Beecroft, I.; Osabuohien, E. Access to and Use of Bank Services in Nigeria: Micro-Econometric Evidence. Review of Development Finance 2014, 4, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Sampson, T.; Zia, B. Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets? Journal of Finance 2011, 66, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.R.; Duru, O.K.; Mangione, C.M. A Community-Based Randomized Controlled Trial of an Educational Intervention to Promote Retirement Saving Among Hispanics. J Fam Econ Issues 2020, 41, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.; McKenzie, D.; Zia, B. The Impact of Financial Literacy Training for Migrants. World Bank Economic Review 2014, 28, 130–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; McKenzie, D.; Zia, B. Who You Train Matters: Identifying Combined Effects of Financial Education on Migrant Households. J Dev Econ 2014, 109, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciol, A.; Quercia, S.; Sconti, A. Promoting Financial Literacy among the Elderly: Consequences on Confidence ✩. J Econ Psychol 2021, 87, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Bilal, D.M.; The, Z.; Bank, W. Who You Train Matters Identifying Complementary Effects of Financial Education on Migrant Households Impact Evaluation Series No 65; 2012;

- Fitzpatrick, K. Does “Banking the Unbanked” Help Families to Save? Evidence from the United Kingdom. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2015, 49, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moahid, M.; Maharjan, K.L. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Access to Formal and Informal Credit: Evidence from Rural Afghanistan. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.; Sain, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Financial Exclusion in Australia: Can Islamic Finance Minimise the Problem?; 2016; Vol. 10;

- Hassan, A. Financial Inclusion of the Poor: From Microcredit to Islamic Microfinancial Services. Humanomics 2015, 31, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotto, J. Examination of the Status of Financial Inclusion and Its Determinants in Tanzania. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R.; Owusu-Frimpong, N.; Dasah, J. Key Motivations for Bank Patronage in Ghana. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2009, 27, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri, L.M.; Kakinaka, M. Financial Inclusion, Mobile Money, and Individual Welfare: The Case of Burkina Faso. Telecomm Policy 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, N.; Khalily, M.A.B. An Analysis of Mobile Financial Services and Financial Inclusion in Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Human Development 2020, 14, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.Y.; Tai, H.T.; Tan, G.S. Digital Financial Inclusion: A Gateway to Sustainable Development. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshan, G.; Yang, D. Motivating Migrants: A Field Experiment on Financial Decision-Making in Transnational Households. J Dev Econ 2014, 108, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, T.M.T.; Tran, Q.N.; Nguyen-Hoang, P.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, T.H. The Role of Learning Motivation on Financial Knowledge among Vietnamese College Students. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin, K.M.; Hodgins, D.C. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Single Session Motivational Intervention for Concerned Gamblers. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2009, 47, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeva, M. Financial Growth in India: Whither Financial Inclusion? Margin 2008, 2, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, B. Survey on Impact Analysis of Access to Finance in Bangladesh; 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.R.; Islam, M.E.; Bank, B. Working Paper Series: WP No. 1603 Financial Inclusion Index at District Levels in Bangladesh: A Distance-Based Approach Financial Inclusion Index at District Levels in Bangladesh: A Distance-Based Approach; 2016;

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics; 2012;

- HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND EXPENDITURE SURVEY HIES 2022 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING; ISBN 9789843542533.

- Khatun, M.N.; Mitra, S.; Sarker, M.N.I. Mobile Banking during COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh: A Novel Mechanism to Change and Accelerate People’s Financial Access. Green Finance 2021, 3, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupas, P.; Robinson, J. Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2013, 5, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, A.; Weill, L. The Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Africa. Review of Development Finance 2016, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njanike, K. An Investigation on the Determinants of Opening a Bank Account in Zimbabwe. Dev South Afr 2019, 36, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandru, P.; Byram, A.; Rentala, S. DETERMINANTS OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION: EVIDENCE FROM ACCOUNT OWNERSHIP AND USE OF BANKING SERVICES; 2016; Vol. 4;

- Willmott, T.J.; Pang, B.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation: An across Contexts Empirical Examination of the COM-B Model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.M.; Loitz, C.C. THE ROLE OF MOTIVATION IN BEHAVIOR CHANGE How Do We Encourage Our Clients To Be Active? LEARNING OBJECTIVES.

- Abdul Razak, A.; Asutay, M. Financial Inclusion and Economic Well-Being: Evidence from Islamic Pawnbroking (Ar-Rahn) in Malaysia. Res Int Bus Finance 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, A.; Nagabhushana, C.; Sarkar, R.; Shah, R.; Singh, G. Financial Access and Women’s Role in Household Decisions: Empirical Evidence from India’s National Rural Livelihoods Project. J Dev Econ 2022, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y. Achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals through Financial Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review of Access to Finance across the Globe. International Review of Financial Analysis 2021, 77, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, Md.N.A. Does Financial Inclusion Promote Women Empowerment? Evidence from Bangladesh. Applied Economics and Finance 2017, 4, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.K.; Karmaker, S.C.; Hosan, S.; Chapman, A.J.; Uddin, M.K.; Saha, B.B. Energy Poverty Alleviation through Financial Inclusion: Role of Gender in Bangladesh. Energy 2023, 282, 128452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Tu, Y. Impact of Financial Inclusion on the Urban-Rural Income Gap—Based on the Spatial Panel Data Model. Financ Res Lett 2023, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, A.; Pino, G. Local Financial Access and Income Inequality in Chile. Econ Lett 2022, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S. Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19.

- Dupas, P.; Karlan, D.; Robinson, J.; Ubfal, D. Banking the Unbanked? Evidence from Three Countries. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2018, 10, 257–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and Opportunities to Expand Access to and Use of Financial Services. World Bank Economic Review 2020, 34, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez Peria, M.S. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2016, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L. Measuring Financial Inclusion: The Global Findex Database; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank, 2012;

- Conroy, J. APEC AND FINANCIAL EXCLUSION: MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR COLLECTIVE ACTION?; 2005; Vol. 12;

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez Peria, M.S. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2016, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prina, S. Banking the Poor via Savings Accounts: Evidence from a Field Experiment. J Dev Econ 2015, 115, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.W.; Rogers, K.E.; Smith, R.C. High School Economic Education and Access to Financial Services. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2010, 44, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoofs, A. Promoting Financial Inclusion for Savings Groups: A Financial Education Programme in Rural Rwanda. J Behav Exp Finance 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Qi, S. Childhood Matters: Family Education and Financial Inclusion. Pacific Basin Finance Journal 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, C.; Toth, R.; Merdikawati, N. Can a Multipronged Strategy of “Soft” Interventions Surmount Structural Barriers for Financial Inclusion? Evidence From the Unbanked in Papua New Guinea. Journal of Development Studies 2022, 58, 2460–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Tran, D.; Goto, D.; Kawata, K. Does Experience Sharing Affect Farmers’ pro-Environmental Behavior? A Randomized Controlled Trial in Vietnam. World Dev 2020, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; De, S. How Much Does Having a Bank Account Help the Poor? Journal of Development Studies 2018, 54, 1551–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Sahu, T.N. Financial Inclusion in North-Eastern Region: An Investigation in the State of Assam. Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management 2022, 19, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Inclusion.

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez, M.S.; The, P.; Bank, W. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts; 2012.

- Chin, A.; Karkoviata, L.; Wilcox, N.; Autor, D.; Banerjee, A.; Craig, S.; Duflo, E.; Juhn, C. Impact of Bank Accounts on Migrant Savings and Remittances: Evidence from a Field Experiment *; 2010.

- Aguila, E.; Angrisani, M.; Blanco, L.R. Ownership of a Bank Account and Health of Older Hispanics. Econ Lett 2016, 144, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Roy, P.K.; Alam, S. The Impact of Banking Services on Poverty: Evidence from Sub-District Level for Bangladesh. J Asian Econ 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njanike, K. An Investigation on the Determinants of Opening a Bank Account in Zimbabwe. Dev South Afr 2019, 36, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayeth Hussain, A.H.M.; Endut, N.; Das, S.; Chowdhury, M.T.A.; Haque, N.; Sultana, S.; Ahmed, K.J. Does Financial Inclusion Increase Financial Resilience? Evidence from Bangladesh. Dev Pract 2019, 29, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Financial Inclusion Strategy.

- Corrado, G. Institutional Quality and Access to Financial Services: Evidence from European Transition Economies. Journal of Economic Studies 2020, 47, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Sahu, T.N. Bank Branch Outreach and Access to Banking Services toward Financial Inclusion: An Experimental Evidence. Rajagiri Management Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujeri, M.K. Improving Access of the Poor to Financial Services; 2015.

- Agarwal, S.; Pulak, S.A.; Soumya, G.; Ghosh, K.; Piskorski, T.; Seru, A.; Banerjee, A.; Beck, T.; Chomsisengphet, S.; Levine, R.; et al. Banking the Unbanked: What Do 255 Million New Bank Accounts Reveal about Financial Access?

- Sarma, M.; Pais, J. Financial Inclusion and Development. J Int Dev 2011, 23, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakara, A.A.; Osabuohien, E.S. Households’ ICT Access and Bank Patronage in West Africa: Empirical Insights from Burkina Faso and Ghana. Technol Soc 2019, 56, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efobi, U.; Beecroft, I.; Osabuohien, E. Access to and Use of Bank Services in Nigeria: Micro-Econometric Evidence. Review of Development Finance 2014, 4, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Sampson, T.; Zia, B. Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets? Journal of Finance 2011, 66, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.R.; Duru, O.K.; Mangione, C.M. A Community-Based Randomized Controlled Trial of an Educational Intervention to Promote Retirement Saving Among Hispanics. J Fam Econ Issues 2020, 41, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.; McKenzie, D.; Zia, B. The Impact of Financial Literacy Training for Migrants. World Bank Economic Review 2014, 28, 130–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; McKenzie, D.; Zia, B. Who You Train Matters: Identifying Combined Effects of Financial Education on Migrant Households. J Dev Econ 2014, 109, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciol, A.; Quercia, S.; Sconti, A. Promoting Financial Literacy among the Elderly: Consequences on Confidence ✩. J Econ Psychol 2021, 87, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Bilal, D.M.; The, Z.; Bank, W. Who You Train Matters Identifying Complementary Effects of Financial Education on Migrant Households Impact Evaluation Series No 65; 2012.

- Fitzpatrick, K. Does “Banking the Unbanked” Help Families to Save? Evidence from the United Kingdom. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2015, 49, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moahid, M.; Maharjan, K.L. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Access to Formal and Informal Credit: Evidence from Rural Afghanistan. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.; Sain, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Financial Exclusion in Australia: Can Islamic Finance Minimise the Problem?; 2016; Vol. 10;

- Hassan, A. Financial Inclusion of the Poor: From Microcredit to Islamic Microfinancial Services. Humanomics 2015, 31, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotto, J. Examination of the Status of Financial Inclusion and Its Determinants in Tanzania. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R.; Owusu-Frimpong, N.; Dasah, J. Key Motivations for Bank Patronage in Ghana. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2009, 27, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri, L.M.; Kakinaka, M. Financial Inclusion, Mobile Money, and Individual Welfare: The Case of Burkina Faso. Telecomm Policy 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, N.; Khalily, M.A.B. An Analysis of Mobile Financial Services and Financial Inclusion in Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Human Development 2020, 14, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.Y.; Tai, H.T.; Tan, G.S. Digital Financial Inclusion: A Gateway to Sustainable Development. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seshan, G.; Yang, D. Motivating Migrants: A Field Experiment on Financial Decision-Making in Transnational Households. J Dev Econ 2014, 108, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, T.M.T.; Tran, Q.N.; Nguyen-Hoang, P.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, T.H. The Role of Learning Motivation on Financial Knowledge among Vietnamese College Students. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin, K.M.; Hodgins, D.C. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Single Session Motivational Intervention for Concerned Gamblers. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2009, 47, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadeva, M. Financial Growth in India: Whither Financial Inclusion? Margin 2008, 2, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, B. Survey on Impact Analysis of Access to Finance in Bangladesh; 2019.

- Hasan, M.R.; Islam, M.E.; Bank, B. Working Paper Series: WP No 1603 Financial Inclusion Index at District Levels in Bangladesh: A Distance-Based Approach Financial Inclusion Index at District Levels in Bangladesh: A Distance-Based Approach; 2016;

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics; 2012.

- HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND EXPENDITURE SURVEY HIES 2022 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING; ISBN 9789843542533.

- Khatun, M.N.; Mitra, S.; Sarker, M.N.I. Mobile Banking during COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh: A Novel Mechanism to Change and Accelerate People’s Financial Access. Green Finance 2021, 3, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupas, P.; Robinson, J. Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2013, 5, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, A.; Weill, L. The Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Africa. Review of Development Finance 2016, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njanike, K. An Investigation on the Determinants of Opening a Bank Account in Zimbabwe. Dev South Afr 2019, 36, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandru, P.; Byram, A.; Rentala, S. DETERMINANTS OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION: EVIDENCE FROM ACCOUNT OWNERSHIP AND USE OF BANKING SERVICES; 2016; Vol. 4;

- Willmott, T.J.; Pang, B.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation: An across Contexts Empirical Examination of the COM-B Model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, W.M.; Loitz, C.C. THE ROLE OF MOTIVATION IN BEHAVIOR CHANGE How Do We Encourage Our Clients To Be Active? LEARNING OBJECTIVES.

| No | Variable | Description and measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | Age of the respondent by year |

| 2 | Gender | Gender of the respondent, 1 equals male, 0 if otherwise |

| 3 | Education | Highest educational attainment by year |

| 4 | Family size | Total family members, by number |

| 5 | Agricultural land size | Agricultural land ownership of the household, by decimal |

| 6 | Total income | Respondent’s monthly total income by BDT |

| 7 | Total expenditure | Respondent’s monthly total expenditure by BDT |

| 8 | Mobile user | Status of mobile subscription, 1equals mobile user, 0 if otherwise |

| 9 | Internet user | Status of internet user, 1equals internet user, 0 if otherwise |

| 10 | Bank Distance | Distance from bank to respondent’s house (in meters) |

| 11 | MFIs Distance | Distance from micro financial institution to respondent’s house (in meters) |

| 12 | MFS distance | Distance from mobile financial service points to respondent’s house (in meters) |

| Treatment variable | ||

| 13 | Motivational workshop, 1equals treatment group, 0 if otherwise | |

| Outcome Variable | ||

| 14 | Account opening | 1 if the respondent opens an account, 0 if otherwise |

| 15 | Bank account opening | 1 if the respondent opens an account in the bank, 0 if otherwise |

| 16 | Micro financial account (MFIs)opening | 1 if the respondent opens an account in MFIs, 0 if otherwise |

| 17 | Mobile financial service (MFS) account opening | 1 if the respondent opens an account in MFS, 0 if otherwise |

| Intervention time | One hour |

| Workshop mode | Oral, interactive discussion, question and answer session. |

| Discussion issue | Institutional and government offers for opening accounts, process of opening accounts, benefit and advantages of saving |

| Intervention provider | Local NGO manager, and agent bank employee. |

| Treatment frequency | Once only for treatment group |

| Variables | Total sample | Treatment (240) | Control (265) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | |

| Age (year) | 33.71 | 8.34 | 34.12 | 8.15 | 33.34 | 8.51 |

| Gender (1=male, 0= female) | .74 | .44 | .76 | .43 | .72 | .45 |

| Education (year) | 9.17 | 1.6 | 9.25 | 1.63 | 9.1 | 1.57 |

| Family size (number) | 4 | 1.16 | 4.06 | 1.2 | 3.95 | 1.13 |

| Agricultural land size (decimals) | 28.42 | 23.53 | 29.81 | 22.98 | 27.17 | 24 |

| Total income (BDT) | 12592.08 | 3474.15 | 12594.58 | 3526.65 | 12589.81 | 3432.6 |

| Total expenditure (BDT) | 10242.97 | 3266.02 | 10067.5 | 3299.87 | 10401.89 | 3233.08 |

| Bank distance (meters) | 4509.21 | 2307.55 | 4403.13 | 2336.68 | 4605.28 | 2281 |

| MFIs distance (meters) | 1668.32 | 1128.57 | 1661.58 | 1126.19 | 1674.42 | 1132.82 |

| MFS distance (meters) | 588.19 | 510.68 | 568.65 | 534.9 | 605.89 | 488.06 |

| Mobile user (1=user, 0= otherwise) | .98 | .12 | .99 | .091 | .98 | .15 |

| Mobile type (1= smart phone, 0= otherwise) | .41 | .49 | .44 | .50 | .39 | .49 |

| Internet user (1= user, 0=otherwise) | .41 | .49 | .44 | .50 | .38 | .49 |

| Variables | Treatment n=240 | Control n=265 | Diff & Std err | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | ||

| Age (year) | 34.12 | 8.15 | 33.34 | 8.51 | -0.78 [0.74] |

| Gender (1= male, 0= female) | .76 | .43 | .72 | .45 | -0.04 [0.04] |

| Education (year) | 9.25 | 1.63 | 9.1 | 1.57 | -0.16 [0.14] |

| Religion (1= Islam, 0= otherwise) | 1 | 0 | .99 | .09 | -0.01 [0.01] |

| Child (number) | 1.29 | .88 | 1.18 | .78 | -0.11 [0.07] |

| Adult (number) | 2.42 | .84 | 2.4 | .8 | -0.03 [0.07] |

| Old people in family (number) | .35 | .6 | .37 | .63 | 0.03 [0.06] |

| Family size (number) | 4.06 | 1.2 | 3.95 | 1.13 | -0.11 [0.10] |

| Agricultural land size (decimals) | 29.81 | 22.98 | 27.17 | 24 | -2.64 [2.10] |

| Agricultural income | 5222.92 | 3884.31 | 5174.72 | 4093.56 | -48.20 [356.03] |

| Non-agricultural income (BDT) | 6718.75 | 4116.04 | 6749.06 | 3571.01 | 30.31 [342.14] |

| Other income (BDT) | 652.92 | 984.01 | 666.04 | 836.28 | 13.12 [8104] |

| Total income (BDT) | 12594.58 | 3526.65 | 12589.81 | 3432.6 | -4.77 [309.88] |

| Food expenditure (BDT) | 5360.42 | 1321.81 | 5779.25 | 1553.14 | 418.83*** [129.01] |

| Educational expenditure (BDT) | 930.83 | 856.8 | 941.51 | 781.66 | 10.68 [72.91] |

| Health expenditure (BDT) | 1387.08 | 843.5 | 1432.08 | 828.77 | 44.99 [74.48] |

| Agricultural expenditure (BDT) | 1507.29 | 1383.25 | 1444.53 | 1419.26 | -62.76 [124.95] |

| Other expenditure (BDT) | 881.88 | 734.42 | 804.53 | 645.58 | -77.35 [61.42] |

| Total expenditure (BDT) | 10067.5 | 3299.87 | 10401.89 | 3233.08 | 334.39 [290.94] |

| Bank distance (meters) | 4403.13 | 2336.68 | 4605.28 | 2281 | 202.16 [205.63] |

| MFIs distance (meters) | 1661.58 | 1126.19 | 1674.42 | 1132.82 | 12.83 [100.66] |

| MFS distance (meters) | 568.65 | 534.9 | 605.89 | 488.06 | 37.24 [45.52] |

| Mobile user (1=user, 0=otherwise) | .98 | .15 | .99 | .09 | -0.01 [0.01] |

| Mobile type (1=smart phone, 0=otherwise) | .39 | .49 | .44 | .5 | -0.05 [0.04] |

| Internet user (1=user, 0=otherwise) | .38 | .49 | .44 | .5 | -0.06 [0.04] |

| Outcome variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total account opening | 93 | 38.75 |

| Account opening in Bank | 25 | 10.42 |

| Account opening in MFIs | 26 | 10.83 |

| Account opening in MFS | 44 | 18.33 |

| Outcome variables | Treatment | Control | Mean diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total account opening | .3875 [.4882] |

.0642 [.2455] |

.3233*** (.0349) |

| Account opening in bank | .1042 [.3061] |

.0038 [.0614] |

.1004*** (.0201) |

| Account opening in MFIs (Micro-financial institution) |

.1083 [.3115] |

.0302 [.1714] |

.0781*** (.0227) |

| Account opening in MFS (Mobile financial service) |

.1833 [.3877] |

.0302 [.1714] |

.1531*** (.0272) |

| Outcome | ATE | ATE | ATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total account opening | .3233*** (.0349) |

.3166*** (.0359) |

.3149*** (.0359) |

| Bank account opening | .1004*** (.0201) |

.099*** (.0203) |

.1023*** (.0210) |

| MFIs account opening | .0781*** (.0227) |

.0835*** (.0232) |

.0721** (.0230) |

| MFS account opening | .1531*** (.0272) |

.1437*** (.0278) |

.1491*** (.0278) |

| Covariates | No | Yes# | With imbalanced variables## |

| Observation | 505 | 505 | 505 |

| Category | Sub sample | Result | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Primary education (n= 296) | .2890*** (.0455) |

.2905*** (.0480) |

| Secondary education (n=123) | .4023*** (.0690) |

.4024*** (.0702) |

|

| More than higher secondary education (n=86) | .3139*** (.0883) |

.2954** (.0999) |

|

| Age | Age ≤ 33 (n=260) | .3658*** (.0510) |

.3342*** (.0520) |

| Age > 33 (n=245) | .2857*** (.0478) |

.2827*** (.0498) |

|

| Total Income | Income 12592 (n=233) | .3415*** (.0490) |

.3295*** (.0520) |

| Income< 12592 (n=272) | .3097*** (.0495) |

.2922*** (.0523) |

|

| Total expenditure |

Expenditure10292 (n=237) | .3305*** (.0520) |

.3380*** (.0548) |

| Expenditure<10292 (n=268) | .3144*** (.0478) |

.2963*** (.0497) |

|

| Occupation | Farmer (n=207) | .3202*** (.0565) |

.3187*** (.0587) |

| Housewife (n=123) | .3423*** (.0758) |

.3399*** (.0745) |

|

| Other occupation (n=175) | .3226*** (.0543) |

.3253*** (.0597) |

|

| Gender | Male (n=374) | .3252*** (.0402) |

.3245*** (.0413) |

| Female (n=131) | .3184*** (.0713) |

.3249*** (.0712) |

|

| Agricultural Land size |

Land 28 decimals (n=260) | .3130*** (.0485) |

.3128*** (.0500) |

| Land size > 28 decimals (n=245) | .3324*** (.0505) |

.3186*** (.0530) |

|

| Family size | Family members 4 (n=157) | .3746*** (.0593) |

.3447*** (.0650) |

| Family members > 4 (n=348) | .2997*** (.0430) |

.3050*** (.0445) |

|

| Covariates | No | Yes | |

| Observations | 505 | 505 |

| Outcome variable | Total sample n=505 | Treatment n=240 |

Control n=265 |

Magnitude | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std dev | Mean | Std dev | Mean | Std dev | ||

| Total account opening | .2178 | .4132 | .3875 | .4882 | .0642 | .2455 | 3.39 |

| Account opening in Bank | .0515 | .2212 | .1042 | .3061 | .0038 | .0614 | 13.55 |

| Account opening in MFIs | .0673 | .2508 | .1083 | .3115 | .0301 | .1714 | 2.24 |

| Account opening in MFS | .1030 | .3042 | .1833 | .3877 | .0301 | .1714 | 3.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).