Preprint

Case Report

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma Misdiagnosed as a Hematoma: Case Report

Altmetrics

Downloads

95

Views

23

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

supplementary.pdf (71.62KB )

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Background: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, accurate diagnosis can be challenging. Here, we present a case of DLBCL that was initially misdiagnosed as a hematoma, highlighting the importance of considering malignancy in the setting of non-responsive soft tissue swelling. Methods: A 76-year-old man presented to the emergency department with right periorbital swelling and ecchymosis. The symptoms first appeared after an injury and did not resolve spontaneously. The patient was taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. A facial bone CT revealed a large irregular homogeneous mass. An extraconal hematoma was suspected based on clinical history and radiologic findings. Incision and drainage were performed, resulting in evacuation of old blood. Despite continued drainage, the patient's symptoms worsened. A comparison with the previous CT revealed an increase in the size of the lesion. As a result, a surgical excisional biopsy was performed. Results: Biopsy of the mass showed a diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes around the tissue. The diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was confirmed pathologically. The patient was referred to hematology for further management. Conclusions: DLBCL is a rare disease associated with a poor prognosis. Due to the previous injury and the use of anticoagulants, the patient was initially misdiagnosed as having a hematoma. This delayed the prompt diagnosis and affected the timing of treatment initiation. We must be aware that a malignant mass is a potential cause of unresponsive soft tissue swelling.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Oncology and Oncogenics

Introduction

Within the head and neck region, lymphoma is the second most common tumor type after squamous cell carcinoma. Lymphoma can occur in extranodal locations throughout the body and doesn't necessarily originate in the lymphatic system [1]. Primary cutaneous lymphoma (PCL) is a rare group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that primarily arise in the skin and typically don't involve lymph nodes or other organs at the time of diagnosis [2]. Among its various subtypes, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma is the most commonly encountered, representing about 20-25% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas [2,3,4]. The 2018 update from the World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer identifies three main subtypes of Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma (pCBCL) as: Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone Lymphoma (PCMZL), Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma (PCFCL), and Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma, Leg Type (PCDLBCL, LT). Among them, Primary cutaneous diffuse B-cell lymphoma is a rare form of Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma, accounting for 10% to 20% of cases and making up only 2% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas [5]. This type of lymphoma is characterized by the rapid growth of reddish or purplish tumor masses. Although Diffuse large B cell lymphoma primarily affects the lower limbs, in 10% to 15% of cases, it may potentially affect areas beyond this region [3]. The rapid growth of this lymphoma is important in differentiating it from other primary cutaneous lymphomas [6]. Nonetheless, it presents with a wide spectrum of clinical features, making accurate diagnosis challenging due to potential overlap with other diseases. Misdiagnosis and delayed recognition of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma can lead to inappropriate treatment and potentially adverse patient outcomes. This study presents a case of Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma initially misdiagnosed as a hematoma, highlighting the importance of including malignancies in the differential diagnosis of unresponsive soft tissue swelling.

2.Case report

A 76-year-old male presented to the emergency department with right periorbital swelling and ecchymosis (Figure 1).

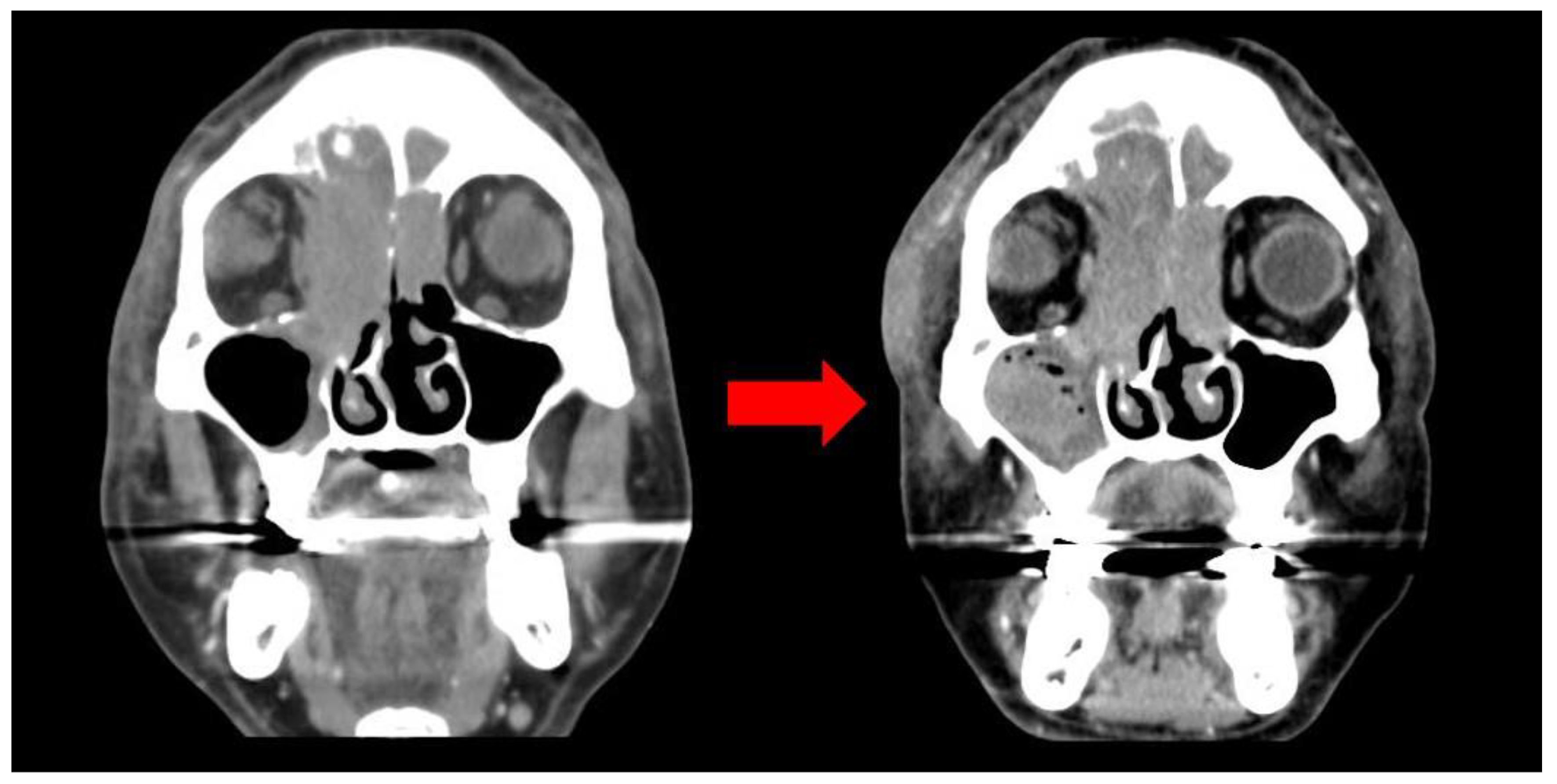

These symptoms began 25 days earlier after sustaining an injury to the right orbital region resulting in a subcutaneous hematoma. The patient was prescribed antibiotics and eye drops for a month at a local clinic, but the hematoma persisted despite attempted aspiration and continued to enlarge. Eventually, it extended to encompass the entire area around the right eye, causing substantial swelling that obstructed the field of vision. The patient was taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation and cerebral infarction, and denied any weight loss, fever, or night sweats. Facial bone CT scan exhibited mucoperiosteal thickening with an air-fluid layer in the right maxillary sinus, and bone damage was identified by a large, non-uniform, and homogeneous mass located in the medial aspect of the right orbit and ethmoid region, resulting in the lateral displacement of the eyeball (Figure 2).

Diagnostic nasal endoscopy was carried out to exclude other illnesses based on the patient's medical history and radiological findings. Nonetheless, no substantial findings other than mucosal swelling were found. In response to the request for improved visibility, an incision and drainage (I&D) procedure was performed following anticoagulant bridging therapy. However, despite continuous drainage, the patient's symptoms continued to worsen. This resulted in the evacuation of a significant amount of old blood. A comparison with the previous CT scan revealed a considerable increase in the size of the lesion, which raised suspicion of a malignant tumor. As a result, the otorhinolaryngology department performed a biopsy via endoscopy. No mass-like lesion was observed during the procedure, and histopathological examination revealed chronic inflammation. As such, surgical excisional biopsy was performed via middle meatal antrostomy (MMA) and inferior neartal antrostomy (INE).

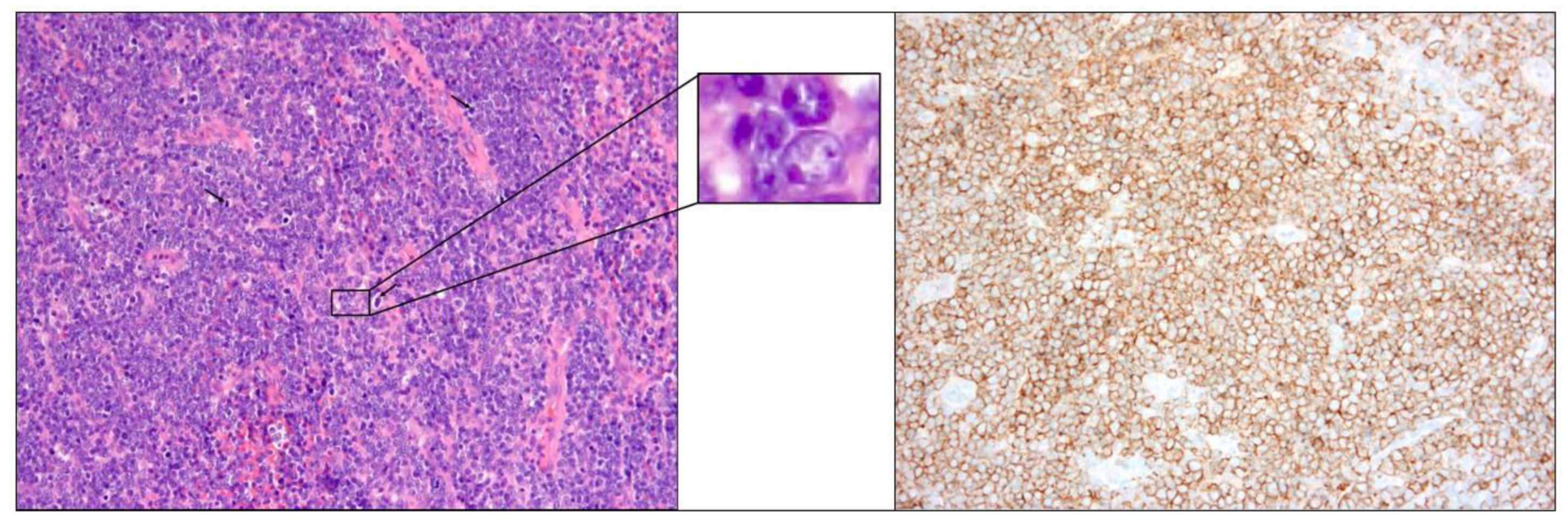

The biopsy of the right medial maxillary and ethmoid mass showed lymphocyte dissemination around the tissue, without evidence of extracutaneous lymphoma. Tumor cells stained for CD20 and bcl-2 protein expression and did not express CD10 (Figure 3).

Additionally, the bone marrow biopsy examination revealed no lymphomatous involvement. The right medial maxillary and ethmoidal mass biopsy confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma diagnosis. The patient was referred to the hematology department for further management, which encompassed chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisolone (R-CHOP). Further tests for staging were conducted, and the PET CT/ Neck CT results indicated no extracutaneous lymphoma. No evidence of lymphomatous involvement was detected upon bone marrow examination. The patient experienced symptom relief following the initiation of appropriate treatment. After six cycles of chemotherapy, a follow-up PET/CT scan confirmed a slight reduction in the size of previous soft tissue lesions in the upper central face, right lateral face, anterior medial wall of the right orbit, and both ethmoid sinuses.

Discussion

Lymphomas are a spectrum of syndromes resulting from the clonal expansion of hematopoietic and lymphoid cells at various developmental stages [7,8]. In roughly 90% of cases, these lymphomas arise from the neoplastic proliferation of B-cells [7,8]. In the head and neck region, malignant lymphomas tend to mainly manifest as lymphadenopathy. Among non-Hodgkin lymphomas, roughly 24% to 48% have extranodal origins, with 8% of this group arising in the ocular adnexa [9,10].

Diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma requires histopathological evaluation, which identifies unique features including dense and diffuse infiltration of non-epithelial cells in the skin and subcutaneous tissues [9,10]. The lymphoma cells typically demonstrate expression of CD20, Bcl-2, CD79a, PAX5, IRF4/MUM1, and FOXPCD20, Bcl-2, CD79a, PAX5, IRF4/MUM1, and FOXP1 are typically expressed by the lymphoma cells. A poorer prognosis is linked to increased expression of post-germinal center markers such as IRF4/MUM1 and FOXP1 [11]. It is recommended to conduct Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER) testing in order to exclude Epstein-Barr virus-associated DLBCL. Bcl-6 expression may vary, while CD 10 is negative. Additionally, for diagnostic and staging determination, as well as exclusion of systemic diseases and treatment, imaging procedures such as PET/CT, laboratory tests including complete blood count and differential count, and a bone marrow biopsy are recommended.

Treatment options include radiation therapy and chemotherapy. For patients with a single lesion, local radiation therapy is the recommended choice [5]. Patients with multifocal skin lesions or relapses should undergo chemotherapy using the CHOP regimen. This treatment consists of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, and is considered the standard chemotherapy for this disease. The response rate for this treatment typically ranges from 40% to 50%. As with all lymphomas, it is advisable to screen for HCV antibodies, HBV surface antigens, and HBV core antibodies before initiating each chemotherapy protocol [11]. This is done to detect any potential viral reactivation and to take appropriate prophylactic measures [11]. Although patients who undergo a combination of chemotherapy and radiation may achieve better clinical outcomes than those treated with only chemotherapy, it should be noted that many DLBCL patients are elderly and frail, making them unsuitable candidates for chemotherapy [12,13]. Furthermore, despite chemotherapy and radiation therapy, recurrence and systemic spread are prevalent [14,15]. This situation adds complexity to the treatment of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. After the initial treatment, the follow-up consists of a comprehensive clinical skin and lymph node examination, laboratory tests, and PET CT evaluations, coupled with annual restaging [16]. After concluding the treatment, PET CT scans are mandatory every 6-12 months.

Although primary cutaneous DLBCL is a rare occurrence, it carries an unfavorable prognosis. The overall 5-year survival rate for DLBCL ranges from 20% to 55% [2]. The number of skin lesions at the moment of diagnosis is essential in assessing these patients. A comprehensive evaluation of lymph nodes and extracutaneous conditions is essential for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The etiological factors that contribute to NHL are diverse and include immunodeficiency, viral infections such as the Epstein-Barr virus and radiation exposure, hybrid genes resulting from translocation, and radioactive contamination. While several reports have documented cases where lymphoma was diagnosed 1 to 2 months after trauma, the etiological role of trauma in the onset of lymphoma is not well understood [16,17,18,19]. Barnett et al. [20] suggested that prolonged or recurrent inflammation resulting from trauma may induce cellular atypia, potentially leading to the development of neoplasia. Additionally, previous facial trauma may create a locus minoris resistentiae where circulating lymphoma cells can accumulate and become trapped, potentially leading to the formation of lymphoma nodules [19]. While the connection between the patient's trauma and the tumor's onset remains unclear, our case can serve as an example of facial lymphoma arising as a result of trauma.

Initially, the absence of typical lymphoma-related symptoms, such as night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue, posed a diagnostic challenge. Moreover, the patient was undergoing long-term warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation. Initially, the examination of nasal endoscopy tissue found no particular lesions, except mucosal swelling. However, suspicion of malignancy was warranted due to the detection of bone erosion and mass effect on CT scans, as well as the observation of a fast-growing mass, despite the lesion persisting beyond the usual one-month healing period. Recognizing that early diagnosis and treatment can significantly improve patient survival rates, it is essential to consider malignancy as a possible cause when dealing with unresponsive soft tissue swelling.

Conclusion

DLBCL is a rare disease with a poor prognosis. Among the different types of DLBCL, cutaneous lymphoma can present with a variety of symptoms, such as hematomas. It is important to consider cutaneous lymphoma as a possible diagnosis if, as in this case, you have a history of trauma and the hematoma persists for more than one month and does not respond to appropriate treatment.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2023-08-062) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital granted exemptions from anonymized data management and patient consent.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Boulaadas, M.; Benazzou, S.; Sefiani, S.; Nazih, N.; Essakalli, L.; Kzadri, M. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the oral cavity. J Craniofac Surg 2008, 4, 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemze, R.; Meijer, C.J.L.M. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a comparison with the REAL Classification and the proposed WHO Classification. Annals of oncology 2000, 11, S11–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Roszkiewicz, J. Primary cutaneous lymphomas. Czelej Lublin 2008, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Sikorska, M.; Florek, A.; et al. Lymphomas of the head and neck in dermatological practice. Postep Derm Alergol 2012, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, P.; et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: an update. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemze, R.; et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019, 133, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, F.; Hiddemann, W.; Pfreundschuh, M.; Rübe, M.; Trümper, L. Maligne lymphome. Onkologe 2002, 8 (Suppl 1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüdiger, T.; Müller-Hermelink, H.K. Die WHO-Klassifikation maligner Lymphome. Radiologe 2002, 42, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulaadas, M.; Benazzou, S.; Sefiani, S.; Nazih, N.; Essakalli, L.; Kzadri, M. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the oral cavity. J Craniofac Surg 2008, 4, 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, J.A.; Fung, C.Y.; Zukerberg, L.; Lucarelli, M.J.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Prefer, F.I.; et al. Lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: a study of 353 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007, 32, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulia, A.; et al. Clinicopathologic features of early lesions of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type: implications for early diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011, 65, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persky, D.O.; Unger, J.M.; Spier, C.M.; et., al. Phase II study of rituximab plus three cycles of CHOP and involved-field radiotherapy for patients with limited-stage aggressive B-cell lymphoma: Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 2258–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.P.; Dahlberg, S.; Cassady, J.R.; et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Vergier, B.; Duncan, L.M.; et. al. Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type.Swerdlow S.H.Campo E.Harris N.L. et. al.WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.2008.International Agency for Research on CancerLyon (France):pp. 242.

- Grange, F.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Courville, P.; et., al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Arch Dermatol 2007, 143, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senff, N.J.; Noordijk, E.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Bagot, M.; Berti, E.; Cerroni, L.; et al. EORTC and ISCL consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008, 112, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, T.; Tahima, T.; Nishio, S.; Nishie, E.; Fukui, M.; Okamura, T. Malignant lymphoma of the scalp at the site of a previous blunt trauma: report of two cases. Surg Neurol 1994, 42, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.F.; Chen, C.T.; Liao, H.T.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, Y.R. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma oft he face presenting as posttraumatic maxillary sinusitis. J Craniofac Surg 2008, 19, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, T.; Tashima, T.; Nishio, S.; Nishie, E.; Fukui, M.; Okamura, T. Malignant lymphoma of the scalp at the site of a previous blunt trauma: report of two cases. Surg Neurol. 1994, 42, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soylu, M.; Ozcan, A.A.; Okay, O.; Sasmaz, I.; Tanyeli, A. Non- Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with uveitis occurring after blunt trauma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2005, 22, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Initial patient picture: right periorbital swelling and ecchymosis.

Figure 2.

CT image (Initial; left, 1 month later; right): large irregular homogeneous mass in the medial aspect of the right orbit.

Figure 2.

CT image (Initial; left, 1 month later; right): large irregular homogeneous mass in the medial aspect of the right orbit.

Figure 3.

Biopsy slide: diffuse infiltration of homogenous tumor cell(left) and CD20 positive(right).

Figure 3.

Biopsy slide: diffuse infiltration of homogenous tumor cell(left) and CD20 positive(right).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated