1. Introduction

The global demand for legumes as foods, feeds, excellent source of bioactive health compounds and raw materials for industrial manufacturing continue to immensely grow due to climate change and increasing human populations [

1]. Generally, this rapid population upsurge, malnutrition, poverty, unemployment, and climate change driven biotic as well as abiotic stress factors dramatically raises pressure on the food systems, especially agricultural legume production [

2]. Nevertheless, the inclusion of improved leguminous crop varieties in cropping systems plays a significant role in alleviating the abovementioned challenges, particularly, global issues such as food insecurity, decreasing soil fertility, and developing climate resilient cultivars that can be grown under adverse environmental conditions [

3,

4].

Plant polyploidisation using antimitotic chemicals such as colchicine serves as one of the techniques that is not yet fully explored for varietal improvements and generation of basic genetic information of grain legumes such as cowpea (

Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.), faba bean (

Vicia faba L.) and soybean (

Glycine max (L.) Merrill.) for enhanced growth and resilience to abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, and waterlogging. Polyploidisation, induced

in vitro,

in vivo or

ex vitro, can cause desirable changes to the morphology, anatomy, physiology, and genomic makeup of crop species, as this technique serves as a viable alternative to genetic engineering technologies such as biolistic microprojectile bombardment, electroporation, CRISPR-Cas, and indirect

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer methods [

5,

6]. Although, biolistic delivery of exogenous DNA into host plant cells has been widely explored for genetic improvement of soybeans and other leguminous and non-leguminous crops, its inconsistencies among bombarded samples for transient gene expression analysis often hinders quantitative determination of putative transgenic plants [

5].

The utility of this approach has also been applied to determine the efficiency of multiple gRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene transfer as also alluded by Hadama

et al. [

7] and Lui

et al. [

8]. These modern genetic manipulation technologies remain constrained by the over-pronounced recalcitrance of crop species, high genotype dependency and excessive costs of operations that renders them inaccessible. However, various reports highlighted that pretreatment of crop seeds with appropriate concentrations of colchicine, duration and immersion conditions may result in the development of morphologically, anatomically, and physiologically modified plants, especially in recalcitrant legumes such as soybean, chickpea (

Cicer arietinum), pea (

Pisum sativum), lentil (

Lens culinaris Medikus) and tepary bean (

Phaseolus acutifolius) (

Figure 1). Although, high dosages may be toxic and lethal to plant cells, the reports also showed that colchicine still contributes to the positive regulation of germination, growth speed and reproductive processes of treated crop plants even under drought stress conditions as shown in

Figure 1 [

9,

10,

11].

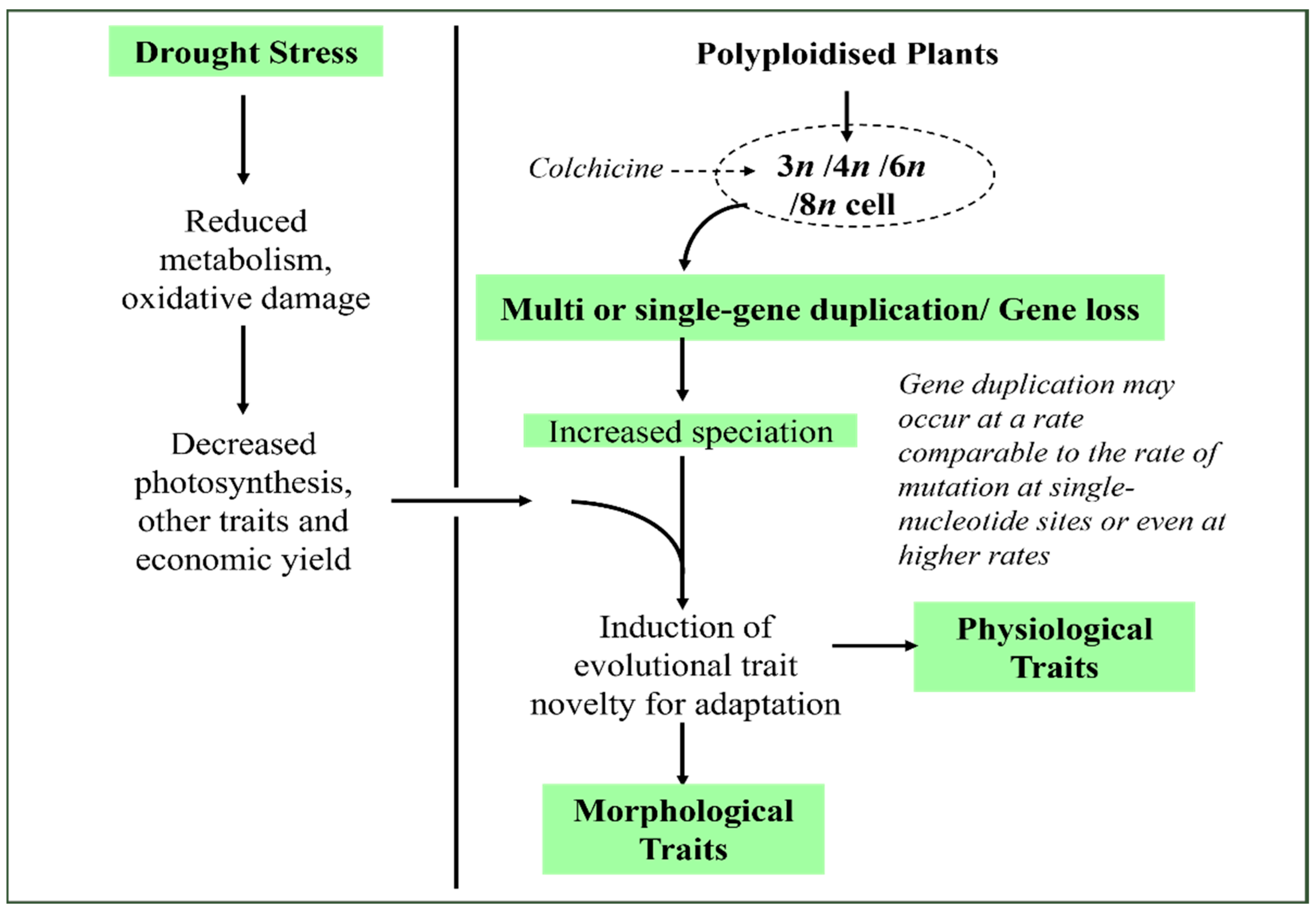

Ploidy induction, as referred by Yadav et al. [

11], instantaneously lead to the formation of new genomic structure or speciation (

Figure 1), wherein, the individual offspring may become ecologically and epigenetically unique from their diploid counterparts. As would be desired by many plant breeders, this provides new lineages upon which further selection and breeding can be carried out for the development of newly improved varieties. However, colchicine-induced polyploidisation in leguminous plant species remains one of the topics scantly researched and reported. As a result of this, the present paper focusses on the progress, achievements, constraints, and perspectives of using colchicine-induced polyploidisation technology to improve the growth and yield of leguminous crop species under drought stress conditions. This paper advocates for the application of colchicine as a plant breeding chemical agent and provides important insights that could encourage the expanded cultivation of legumes in drought-affected agricultural fields.

2. Role of drought stress on growth and yield of leguminous crops

Drought serves as one of the most important abiotic constraints that inflicts severe damaging effects to the growth and yield of leguminous crops. This stress has been reported as an inevitable factor that exists in various environments [

12], negatively influencing crop production, biomass, and yield quality by altering morphological, physiological, and molecular responses in affected plants [

13].

Table 1 shows a summary of some of the growth and developmental aspects of plants that are negatively impacted or increased (i.e., floral/pod abortions, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), proline content and malonaldehyde content) because of the exposure of plants to drought stress. Many legumes and non-leguminous crops exhibit these high levels of sensitivity and susceptibility to drought stress than any kind of abiotic constraints. In legumes, crop growth and yields are severely impacted by inadequate supply of water, which results in decreased carbon assimilation content and rates. This deadly impact and reducing effects take place regardless of the stages of plant growth [

14].

Generally, all crop plants that are cultivated under open environments remain at a high risk of passing through a brief or prolonged period of abiotic stress at any point during their life cycle. However, different crops exhibit varying sensitivity and susceptibility to drought stress, and presents dissimilar effects on metabolic activities, growth, and development of individual genotypes. In addition to leaf photosynthetic capacity, shoot biomass and seed weight, drought stress disrupted sucrose metabolism and transport balance of photoassimilates in both leaves and seeds of soybeans [

15]. Drought also decreased the yield of chickpea (

Cicer arietinum) by about 45−50% through interference with seedling and early vegetative growth stages. Under high temperatures, that also exacerbate water-deficit, chickpea also suffered severe cytoplasmic water losses that concomitantly led to flower and fruit abortions, reduced seed sizes, loss of pollen viability and fertility that affected pod set, and ultimately reduced the yield of this crop [

16].

Apart from the effects mentioned above, drought can have massive destructive effects on the growth and development of commercially valuable leguminous crops such as lentils, faba bean, common bean (

Phaseolus vulgaris) and cowpea, with higher magnitude impairment on the source and sink relations during vegetative and reproductive growth stages of the plants [17‒20]. In comparison, drought stressed plants showed reduced morphological traits such as the leaf area, number of branches, stem diameter and root length than in water-stress free leguminous plants. Additionally, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) together with malonaldehyde (MDA) content as illustrated in

Table 1 were also increased [

15]. Drought stress also significantly decreased the accumulation of biochemical substances (

Table 1) which inevitably impairs metabolism and photosynthetic activities leading to plant mortality [

21,

22].

Table 1.

Aspects of plant growth and development influenced by drought stress in both leguminous and non-leguminous crop species.

Table 1.

Aspects of plant growth and development influenced by drought stress in both leguminous and non-leguminous crop species.

| Growth |

Reproductive |

Physiological |

Biochemical |

Seed germination,

plant height,

number of branches, number of leaves,

stem diameter, leaf area,

root development, and

nodulation |

Flowering,

flower abortion, fruiting, pod abortion,

number of seeds per pod, pod size,

seed size,

100-seed weight, and

yield per hectare |

Antioxidant, catalases,

glutathione/ ascorbate-glutathione,

superoxide dismutase,

inorganic ions (Na+, K+, N, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, Mn, and B),

reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

Abscisic acid (ABA), amino acids, carotenoids, DNA, RNA, proteins, Proline content,

reducing sugars, non-reducing sugars, proline, starch, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, malonaldehyde, phenols, and alkaloids. |

3. Impact of polyploidisation on alleviating the effects of drought stress

Most leguminous crops are well adapted to tropical and subtropical environmental conditions. However, the magnitude of abiotic stresses that occur in these regions results in massive losses of yields, with drought being the main contributor of many previously recorded reductions in crop production [

28]. As more incidences of drought continue to occur, circumventing the vulnerabilities associated with crop production under drought stress conditions remains a key research priority. In this regard, the expansion of germplasm through synthetic crop polyploidisation using mutagenic chemicals such as colchicine could represent a viable alternative for biotechnology-based genetic improvements. Colchicine is an alkaloid that is usually extracted from a Colchicaceae species,

Gloriosa superba L. (Flame Lily), the only species in this genus, and order Liliales. This chemical is also present in the seeds of

Colchicum autumnale L. and

Colchicum luteum L. [

29].

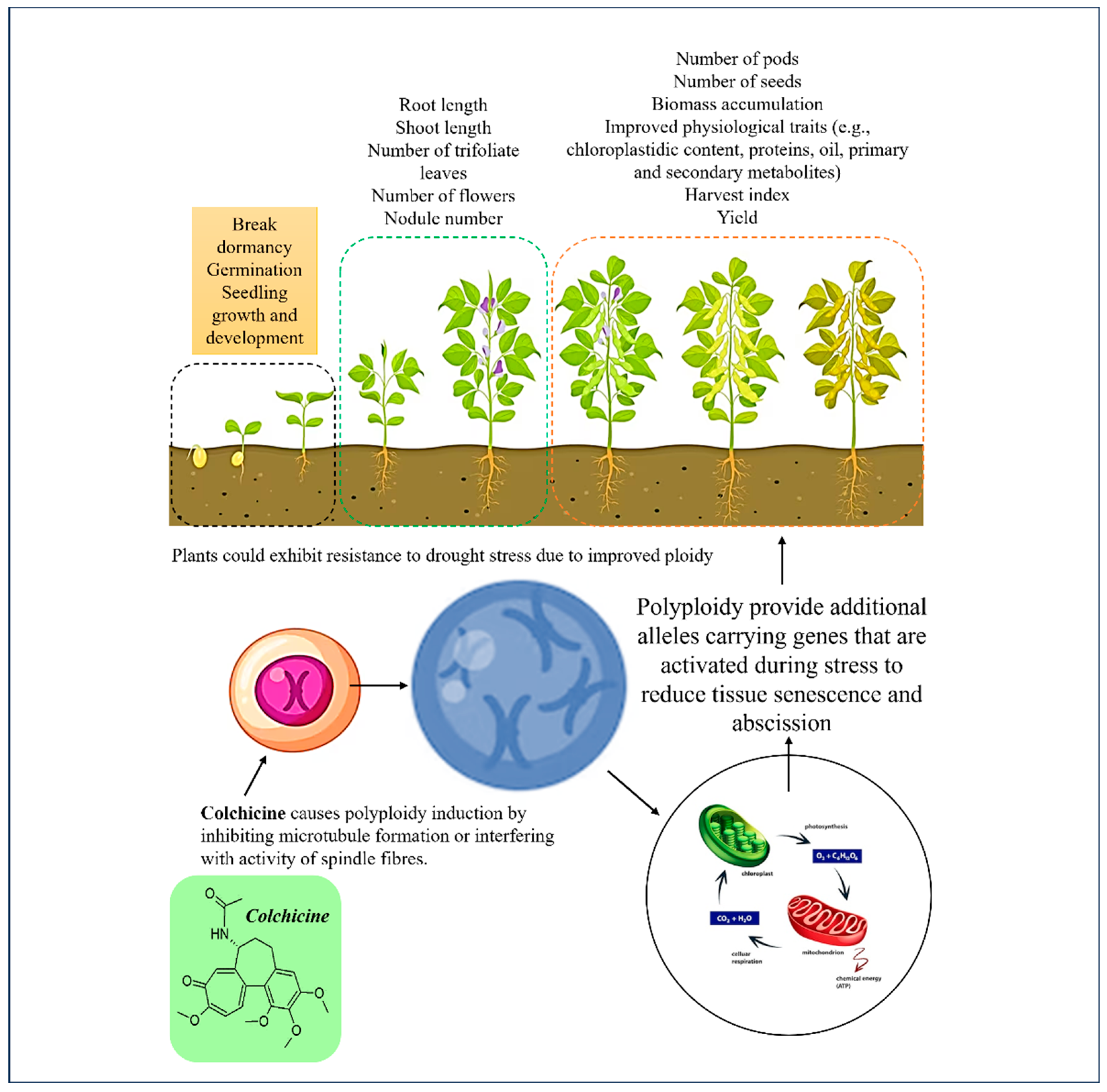

Colchicine plays a vital role as a mutagenic agent, causing the multiplication of sets of plant chromosomes which has already became a method of choice for inducing genetic mutations (

Figure 2). Plant polyploidisation gradually and naturally takes place as a method for speciation, formation of new species, through the increase in the number of chromosomes [

30]. The increase in the number of chromosomes using colchicine induced polyploidisation was reported to result in plants showing enhanced sizes of morphological characters such as larger leaves, flowers, and seeds (

Table 1). Eng and Ho [

3] also reported that this artificial polyploidisation can be used as a strategy for adaptation of species, particularly of horticultural crops. In legumes, evaluation of nodule number, nodule size, terminal bacteroid differentiation, symbionts quality (nodule environment, partner choice, host sanctions etc.) revealed that plant polyploidy enhanced some key aspects of legume-rhizobia mutualism [

31].

However, the use of this mechanistic hypothetical approach failed to explore the underlying mechanisms and influence of host benefits emanating from this mutualistic relationship of legumes with the involvement of rhizobia [

31]. Nevertheless, this mutualism regulates the nutrient cycle in natural ecosystems and provides altered nitrogen (N) fixation rates leading to further environmental adaptations. Although, it is fully understood that plant polyploidy affects plant phenotype and genotype, much less is known about how it influences the interactions of plants with abiotic stresses, particularly, constraints such as drought.

4. Growth analysis of drought-stressed polyploidised leguminous plants

As previously mentioned, the impact of drought stress on crop production continues to intensify, increasing yield losses, causing food production reductions and spikes in food prices. Many studies reported that these reductions take place due to the detrimental effects that drought has on the growth and development of crop plants [22,32‒36]. The cited reports discussed various ways in which drought impaired plant growth and development, but also present potential strategies in which this abiotic stress could be circumvented. To confer drought tolerance in legumes, crop plants can be improved through colchicine-induced polyploidisation (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). As already discussed, this approach may lead to intraspecific variations in traits associated with drought stress. Colchicine causes changes in the morphological characteristics of roots and shoots, and even in traits associated plant responses to cope with progressive drought (

Table 2). Earlier, Essel et al. [

37] reported changes on the quantitative characters such as percentage germination, plant height, number of leaves, length of longest branches and number of branches, including pod number and yield in cowpea plants developed from seeds treated with 0.05g/dl−0.20g/dl of colchicine.

Although, colchicine had reduced the germination percentage in seeds treated with 0.10 g/dl, 0.15 g/dl and 0.20 g/dl, improvements were reported in most of the quantitative characters of colchicine polyploidised cowpea plants. Similarly, colchicine-induced genetic variability in cowpea was observed through phenotypic changes in seedling emergence percentage, plant height, number of leaves, nodes, and survival percentage of the plantlets [

38]. These morphological improvements have also been reported as valuable supplements to enhance plant response to drought stress. For instance, the increase in plant height demonstrates increased plant cell growth, that if decreased, this may alter water and nutrient potential and movement into or out of plant cells. As earlier reported by Nonami et al. [

39], cell enlargement in combination with drought decreases this potential difference, subsequently inhibiting the growth of plants. Furthermore, water movement can be impeded by both water shortage and by the small cells observed during reduced plant growth. These abovementioned effects have been considered like the number of leaves and branches, which were reported to signify improved plant response to drought stress.

Plant leaves improve drought resistance by increasing wax coverage, cuticle thickness, osmiophilicity [

40] and reduced number of branches, leading to combined effects of drought and exposure of plant shoots to photosynthetically active irradiation due to the overall reduction in plant architecture compared to water-stressed diploid plants. These observations were made in common bean (

Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Berna) by Durigon et al. [

41]. As drought remains one of the key factors restricting successful establishment of effective plant architecture determined by the degree of branching, length of internodes and shoot determinacy [

42]. Therefore, plant polyploidisation can thus be used to improve plant shape or architecture which is a primary determinant of growth, productivity, and yield of various leguminous crops. Additionally, traits such as leaf area, shoot and root biomass, as well as the root length indicated in

Table 2 also form part of the key plant adaptive strategy to enhance carbon-sequestration capacity [

43].

Table 2.

Comparative evaluation of seed germination and morphology of a few polyploidised leguminous crops developed by imbibing seeds in colchicine solution for different durations, and responses from their diploid counterparts.

Table 2.

Comparative evaluation of seed germination and morphology of a few polyploidised leguminous crops developed by imbibing seeds in colchicine solution for different durations, and responses from their diploid counterparts.

| Parameter |

Legumes |

Colchicine (mg/l) |

Duration (hours) |

Polyploids |

Diploids |

References |

| Germination (%) |

Chickpea, cowpea, mungbean, soybean |

0.025−0.5 |

3−6 |

90−92* |

90−100* |

Aliyu et al. [44] |

| Shoot height (cm) |

Chickpea, Cluster bean |

0.1−15.0 |

4−24 |

8.02* |

4.42* |

Vijayalakshmi and Singh [45] |

| Branch no./plant |

Cowpea, Azuki bean |

01−2.0 |

3−12 |

4.06 |

3.94 |

Ajayi et al. [46] |

| Leaf no./plant |

Faba bean, winged bean, cluster bean |

0.1−25.0 |

4−24 |

29.0* |

15.67* |

Ajayi et al. [46] |

| Leaf area (cm2) |

Winged bean, faba bean |

0.005−15 |

8−24 |

223.4* |

32.72* |

Udensi et al. [47] |

| Root length (cm) |

Cluster bean |

25.0 |

24 |

7.20* |

4.85* |

Vijayalakshmi and Singh [45] |

| Shoot biomass (g) |

Soybean |

0.15 |

2 |

3.15 |

2.96 |

Shehu et al. [10] |

| Root biomass (g) |

Soybean |

0.15 |

2 |

1.63* |

1.15* |

Shehu et al. [10], Essel et al. [37] |

5. Yield evaluations in polyploidised legume plants affected by drought stress

As reported by a significant number of researchers, polyploidisation lead to improved yield components. In alfalfa (

Medicago sativa), dry mass yields differed according to the cultivar used, and early harvest was also decreased due to water shortage [

33]. Although, it is well known that leguminous plants, regardless of their use as forage or grain crops, they differ in terms of yield and other morpho-physiological parameters and remain highly drought stress sensitive (

Table 3). As a result, drought stress has variable effects on growth, productivity, and yield of these crops. Under water stress free conditions, polyploidised cowpea plants showed early flowering and fruiting, possibly due to the physiological changes caused by the mutagen as reported by Essel et al. [

37]. But the use of increased colchicine concentration also interfered with maturity and early flowering. As expected, the efficiency of plant polyploidisation induction system also depends on the colchicine concentration used, treatment duration and nature of treated plant materials [

30]. Other yield traits that were significantly influenced by the chemical mutagens applied included enhanced seed formation ability, number of pods per plant and yield per plant, which were increased in some of the colchicine treatments compared to the control diploid plants [

11,

38].

Even though, colchicine has been used to improve the growth of cowpea, mung bean, alfalfa, and other leguminous crops, as well as their various yield components, this mutation inducing technique still needs to be thoroughly investigated for obtaining new useful traits and creating new genetic variability against abiotic stress. This genetic variability is what is needed in order to develop drought resilient crops and achieving food security. However, in contrast, Vijayalakshmi and Singh [

45] earlier reported contrasting results of colchicine induced reductions in fruiting and pod characters such as pod circumference, pod length and pod weight in cluster bean [

Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub]. Cluster bean serves as one of the most important major self-pollinated pulse crops in India, but its yield parameters were significantly decreased with the increasing concentrations of colchicine that was used to soak the seeds before sowing.

Although, colchicine and other mutagenic chemicals are required for rapid increase in the rates of yields over a reasonable period, mutagenesis through this chemical also revealed both negative and positive effects on crop growth and yields [

46]. With the increased pressure of climate change and frequency of severe drought events, other mutagenic chemicals such as sodium azide and gamma rays could be explored to increase genetic variability in the agronomic traits and yields. The use of such chemicals and technique in mutation breeding were explored for two cowpea varieties treated with different doses of gamma rays and sodium azide [

47]. The study reported improvements in the yield traits as shown in

Table 3, including the number of seeds per pod and seed weight which positively correlated with improved yield as a result of these treatments. As the global attention on legumes is based on yield quantity and quality, plant polyploidy can be used to minimise production constraints of legumes, even under drought conditions.

Table 3.

Estimates of yield components and biochemical parameters of diploid and polyploidised leguminous plants obtained by calculating averages for each parameter per plant.

Table 3.

Estimates of yield components and biochemical parameters of diploid and polyploidised leguminous plants obtained by calculating averages for each parameter per plant.

| Parameter |

Polyploids |

Diploids |

References |

| No. of flowers |

27.7 |

10.3 |

Udensi et al. [49] |

| No. of pods |

33.0 |

19.33 |

Ikani et al. [50] |

| 100-seed weight (g) |

44.5 |

38.5 |

Aliyu et al. [44] |

| Yield/ hectare (kg) |

4682.6 |

2886.3 |

Esho et al. [51] |

| Proteins (µg/g) |

223.4 |

32.72 |

Yadav et al. [11] |

| DNA (µg/g) |

31.2 |

25.0 |

Yadav et al. [11] |

| RNA (µg/g) |

245.0 |

190.0 |

Yadav et al. [11] |

6. Effect of polyploidisation on seed and nutritional quality

The twin effects of drought and heat stress primarily serve as major constraints in crop production and agricultural sustainability. These stresses obstruct productivity at various vegetative and reproductive phases of crop growth [

52], but with seed filling stage suffering substantial damage. Drought affects yield as discussed in the previous sections (

Table 3) simultaneously causing reductions in grain quality by affecting seed size and weight [

53]. Seed filling is negatively influenced by reducing the ability of seed sink strength by decreasing the number of endosperm cells and amyloplasts formed as reported by Sehgal

et al. [

52]. Furthermore, drought stress induces tissue senescence and enhance remobilisation of photoassimilates from seed filling to the various plant parts affected by stress [

54]. As anticipated, the drought induced reduction of assimilates supply to developing grains significantly influences seed size and weight.

In lentil (

Lens culinaris Medikus), drought also interfered with nutritional quality by decreasing protein content, zinc (Zn), and iron (Fe) concentrations in the seeds [

55]. As Sehgal

et al. [

52] further indicated, drought impaired mineral uptake, damaged membranes, reduced photosynthetic rates ad stomatal conductance. These then, have negative impacts on the production and mobilisation of assimilate nutrients to the developing seeds in various leguminous and non-leguminous crop species. Inhibited endosperm cell division and reduced number of starch granules markedly influence grain carbohydrate composition. Further effects include, small size of starch grains, lower amylase content, reduced nutrients translocation, mineral and ion transport, such as iron, zinc, sulfur (S), magnesium (Mg) and phosphorus (P) that are also highly required for serious enzymes related activities, and synthesis of primary as well as secondary metabolites [56‒59].

In general, drought reduces nutrient acquisition and the concentrations of major nutrient-uptake through the roots, which are correlated with the decrease in photoassimilation and redistribution from the source to the sink, especially during seed filling stages of crop growth. Although, the impact of water-deficit on seed and nutritional quality of grains is well characterised in legumes and other crops, very scant information is available on the seed and nutritional quality response of plant polyploidy under drought stress conditions.

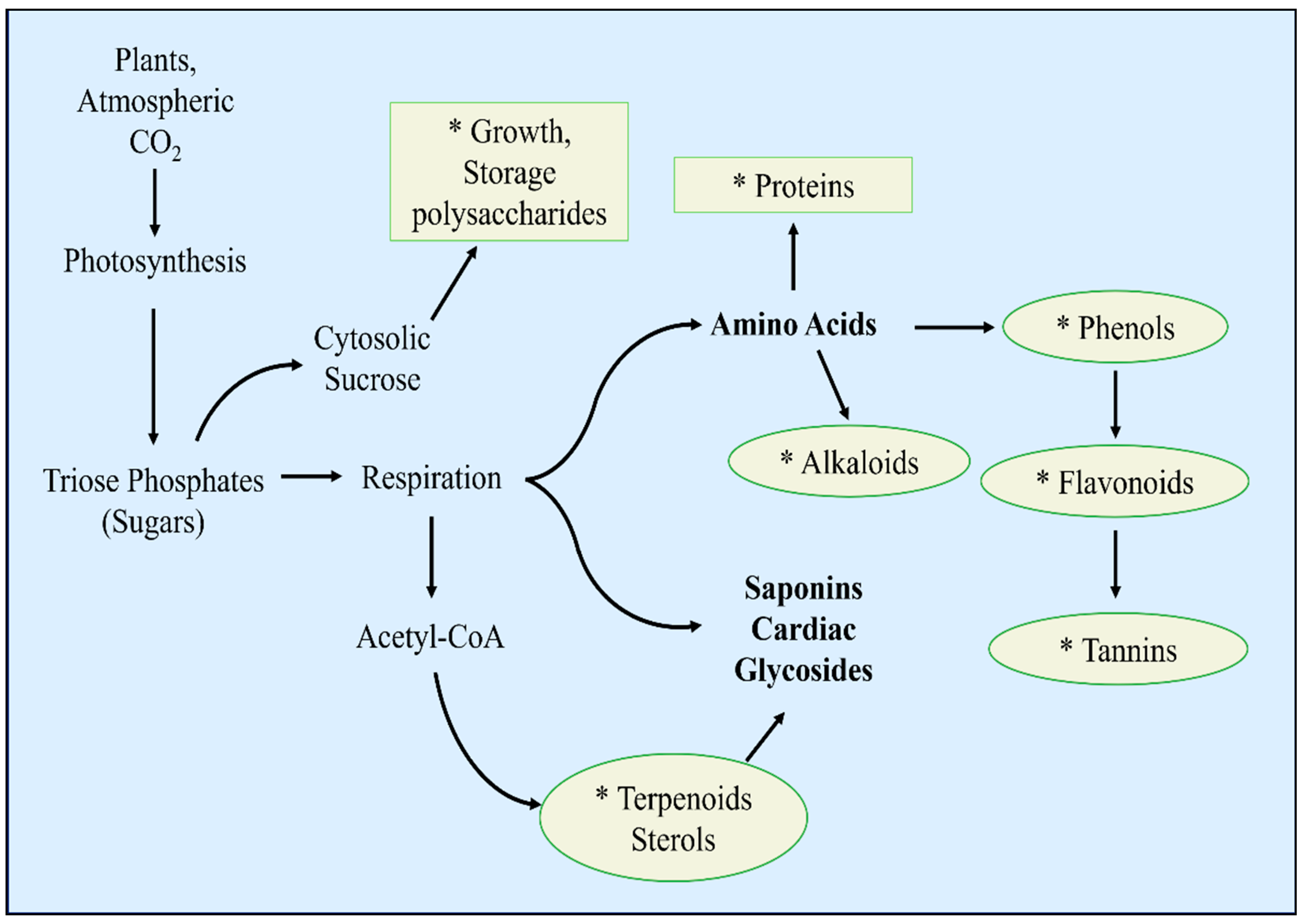

7. Ploidy stability under drought stress conditions

The hereditary control of plant growth is contained largely within the DNA of cell chromosomes. As the most powerful and versatile molecule, DNA serves as a recipe coding for thousands of different proteins that help living organisms, including plants to interact with each other and respond effectively to environmental stress challenges [

60]. The DNA regulates, through the messenger RNA, the kinds of proteins and enzymes that function to control cell structure and plants’ responses to stress (

Figure 3). Many previous and current studies utilised the DNA from different sources, often assembling it into gene constructs to drive biological research and biotechnological advances [

61]. This includes tools such as exploring quantitative trait loci (QTL) and polyploidy induction on crop improvement. However, it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of natural speciation and those inflicted by artificial polyploidisation. Trait comparison, for instance in characters that are the same in natural diploids and synthetic polyploids but different in naturally occurring polyploidised lineages can be helpful in identifying any existing negative effects in synthetic polyploids [

62].

Colchicine, like trifluralin and oryzalin, operates by blocking the cell cycle in developing plant tissues, this can cause genome instability and many direct phenotypic consequences that are undesirable, but can be eliminated through selective breeding [

63]. Colchicine duplicate chromosome number, but it still not clear, how this influences the functions and maintenance of genes, including the expression of secondary metabolites (

Figure 3). Plant secondary metabolites play a key role in crop response to drought stress, but genome-wide studies of gene expression in polyploidised plants demonstrated the differences in the composition and concentrations of metabolite profiles according to ploidy level. Although, highly inconsistent, Gaynor et al. [

64] found significant differences on plant secondary metabolites based on the whole-genome duplication. Such effects on the metabolism as indicated on

Figure 3 are responsible for the shifts in both physiological and phenotypic traits which confers tolerance to various ecological stress factors. As discussed by this paper, the improved morphological and physiological responses in plants as a result of increased genome size is hypothetically responsible for providing competitive advantage for growth and quick diversification in polyploids compared to their diploid counterparts [

65].

Even though, the routine use of artificial doubling of chromosome complements in legumes remain highly improbable, especially due to the recalcitrance in crops such as soybean, cowpea and faba bean. The effect of induced polyploidy in leguminous crops, as compared to other non-leguminous crop species, and the possible differential response of polyploidised varieties to environmental constraints will still presents major challenges. This group of dicot crops overwhelmingly appear to fail in responding better to genetic improvement protocols, especially under the changing climatic conditions, because of the lack of routine and effective breeding systems [1‒5,50,68]. While genetic engineering and induced-polyploidisation continue to seem unachievable, stable and efficiently reproducible protocols for the development of legume polyploids remains a prerequisite to deal with the adverse effects of drought stress. Furthermore, polyploidy instability in these crops that entails by far the general characterisation of leguminous polyploids that have failed to be established into improved gene resources required for further genetic manipulation of the individual crop species cannot be tolerated. For instance, according to numerous cited reports, 58−100 %, 4.42−8.02 cm, 1.43−44.5 g and 7.61−4682.55 kg/ha of mean germination, plant height, 100-seed weight and yield per hectare, compared to 90−100%, 4.85−7.20 cm, 0.39−38.5 g and 6.85−2886 kg/ha of the same parameters were recorded in both polyploidised and diploid soybean plants, respectively [

11,

30,

31,

68]. The lack of trait uniformity in the polyploids, compared to diploid species, demonstrates the unequal and inconsistent distribution of chromosomes produced in reproductive cells containing varying degrees of chromosomal imbalances. Consequently, plants developed from these cells become almost completely sterile, with dysfunctional male and female reproductive cells that markedly indicated the instability of polyploid and aneuploidy leguminous plants.

5. Conclusions

The polyploidisation of leguminous crops using colchicine has been tested for almost more than a century across the globe. Colchicine remains the most preferred antimitotic agent in plant polyploidy production, compared to mutagenic chemicals such as sodium azide, oryzalin and hydroxylamine. Although, research in plant polyploidy has recently increased, information on the polyploidisation of leguminous crop plants remain elusive, particularly, the responses of polyploids under drought stress conditions. This suggest that any new milestone achieved for both in vitro or in vivo or ex vitro colchicine induced polyploidy will open new avenues for the genetic manipulation of these crops to confer stress tolerance. As previously reported, the current trend of polyploidisation in horticultural plants has already proceeded beyond addressing challenges involving unequal distribution of chromosomes and studying the ploidy outcomes, as well as evaluating polyploidised plants through functional, metabolomic and genomic studies. These approaches should also be encouraged and further explored for the genetic improvement of leguminous crops to confer tolerance to abiotic stress factors such as drought and salinity constraints in leguminous crops.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P and M.N.P.; data curation, M.N.P; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P; supervision, M.P; funding acquisition, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Department of Research Administration and Development of the University of Limpopo.

Data Availability Statement

Data that supports the analysis and discussions made in this review paper are freely available as per citations and on various online research platforms.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful for the continued support provided by the Department of Biodiversity and the University of Limpopo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahama, A.; Awuni, J.A.; Mabe, F.N.; Azumah, S.B. Modelling adoption intensity of improved soybean production technologies in Ghana: A generalized poisson approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thosago, S. The performance of soybean as influenced by inoculation and soil moisture conservation techniques. In: Mangena P, editor. Legumes- nutritional value, health benefits and management. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.; 2023. p. 15-48.

- Handayani, L.; Rauf, A.; Rahmawary; Supriana, T. The strategy of sustainable soybean development to increase soybean needs in North Sumatera. IOP Conf Series: Earth & Environ Sci. 2018, 112, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A.Y.; Oyinbo, O.; Manda, J.; Kamsang, L.S.; Kamai, N. Adoption of improved soybean and gender differential productivity and revenue impacts: Evidence from Nigeria. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Eggenberger, A.L.; Lee, K.; Liu, F.; Kang, M.; Drent, M.; Ruba, A.; Kirscht, T.; Wang, T.; Jiang, S. An improved biolistic delivery and analysis method for evaluation of DNA and CRISPR-Cas delivery efficacy in plant tissue. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, L.; Ran, Y. Progress in soybean genetic transformation over the last decade. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 900318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.; Liu, Y.; Nagira, Y.; Miki, R.; Taoka, N.; Imai, R. Biolistic-delivery-based transient CRISPR/Cas9 expression enables in planta genome editing in wheat. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 14422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, J.; Godwin, I.D. Genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in sorghum through biolistic bombardment. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1931, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanko, D. Effects of colchicine and its application in cowpea improvements: Review paper. Int J Current Innov Res. 2007, 3, 800–804. [Google Scholar]

- Shehu, A.S.; Adelanwa, M.A.; Alonge, S.O. Effect of colchicine on agronomic performance of soybean (Glycine max). Int J Res 2016, 3, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Rodrigues, S.; Sequeira, R.; Palambe, S. Effect of colchicine on Vigna radiata L. Int J Bot Stud. 2021, 6, 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants. 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Ashraf, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Men, S.; Wang, L. Chilling and drought stresses in crop plants: Implications, cross talk, and potential management opportunities. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguz, M.C.; Aycan, M.; Oguz, E.; Poyraz, I.; Yildiz, M. Drought stress tolerance in plants: Interplay of molecular, biochemical, and physiological responses in important development stages. Physiologia 2022, 2, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, L.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Xie, F. Effect of drought stress during soybean R2–R6 growth stages on sucrose metabolism in leaf and seed. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Devi, P.; Jha, U.C.; Sharma, K.D.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Nayyar, H. Developing climate-resilient chickpea involving physiological and molecular approaches with a focus on temperature and drought stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Sita, K.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Siddique, K.H.; Nayyar, H. Effects of drought, heat, and their interaction on the growth, yield and photosynthetic function of lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) genotypes varying in heat and drought sensitivity. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y. Drought stress impact on leaf proteome variations of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau of China. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Dinglasan, E.; Veneklaas, E.; Polania, J.; Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Merchant, A. Effect of drought and low P on yield and nutritional content in common bean. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 814325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Moreira, R.; Pais, I.; Semedo, J.; Simões, F.; Veloso, M.M.; Scotti-Campos, P. Cowpea physiological responses to terminal drought- comparison between four landraces and a commercial variety. Plants 2022, 11, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.; Katiyar, D.; Hemantaranjan, A. Drought mitigation strategies in pulses. Pharm. Innov. J. 2019, 8, 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Khatun, M.; Sarkar, S.; Era, F.M.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Anwar, M.P.; Fahad, S.; Datta, R.; Islam, A.K.M.A. Drought stress in grain legumes: Effects, tolerance mechanisms and management. Agron. 2021, 11, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.; Jan, S.A. Approaches for sustainable production of soybean under current climate change condition. MOJ Biol Med. 2023, 8, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Li, J.; Yahya, M.; Sher, A.; Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, L. Research progress and perspective on drought stress in legumes: A review. Int J of Mol Sci. 2019, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccari, S.; Elloumi, O.; Chaari-Rkhis, A.; Fenollosa, E.; Morales, M.; Drira, N.; Ben Abdallah, F.; Fki, L.; Munné-Bosch, S. Linking leaf water potential, photosynthesis and chlorophyll loss with mechanisms of photo- and antioxidant protection in juvenile olive trees subjected to severe drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 614144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Ahmad, T.; Bashir, A.; Hafiz, I.A.; Silvestri, C. Studies on colchicine induced chromosome doubling for enhancement of quality traits in ornamental plants. Plants. 2019, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Vennam, R.R.; Shrestha, A.; Shrestha, A.; Reddy, K.R.; Wijewardane, N.K.; Reddy, K.N.; Bheemanahalli, R. Resilience of soybean cultivars to drought stress during flowering and early-seed setting stages. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.D.; El-Baidouri, M.; Abernathy, B.; Iwato-Otsubo, A.; Chavarro, C.; Gonzales, M.; Libaut, M.; Grimwood, J.; Jackson, S.A. A comparative epigeonomic analysis of polyploidy-derived genes in soybean and common bean. Plant. Physiol. 2015, 168, 1433–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkrishna, A.; Das, S.K.; Pokhrel, S.; Joshi, A.; Verma, S.; Sharma, V.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, N.; Joshi, C.S. Colchicine: Isolation, LC–MS QTof screening, and anticancer activity study of Gloriosa superba seeds. Mol. 2019, 24, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, W.H.; Ho, W.S. Polyploidization using colchicine in horticultural plants: A review. Scientia Horti. 2019, 246, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, N.J.; Ashman, T.L. The direct effects of plant polyploidy on the legume-rhizobia mutualism. Ann Bot. 2018, 121, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Tremblay, N.; Zarco Tejada, P.J.; Dextraze, L. Integrated narrow-band vegetation indices for prediction of crop chlorophyll content for application to precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Peñuelas, J. Relationship between light use efficiency and photochemical reflectance index in soybean leaves as affected by soil water content. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 5109–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.A. Global synthesis of drought effects on cereal, legume, tuber, and root crops production: A review. Agric Water Manag. 2017, 179, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathobo, R.; Marais, D.; Steyn, J.M. The effect of drought stress on yield, leaf gaseous exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agric Water Manag. 2017, 180, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, A.L.; Gonzalez, E.M.; Roy; Choudhury, S. ; Signorelli, S. Editorial: Drought stress in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1026157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essel, E.; Asante, I.K.; Laing, E. Effect of colchicine treatment on seed germination, plant growth and yield traits of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp). Canad J Pure Appl Sci 2015, 9, 3573–3576. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, A.T.; Ohunakin, A.O.; Osekita, O.S.; Oki, O.C. Influence of colchicine treatments on character expression and yield traits in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp). Global J Sci Front Res: C Biol Sci. 2014, 14, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nonami, H.; Wu, Y.; Boyer, J.S. Decreased growth-induced water potential (a primary cause of growth inhibition at low water potentials). Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response mechanism of plants to drought stress. Horti. 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durigon, A.; Evers, J.; Metselaar, K.; de Jong van Lier, Q. Water stress permanently alters shoot architecture in common bean plants. Agron. 2019, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmann, T.; Muhr, M. Shaping plant architecture. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Wei, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, L. Plant root-shoot biomass allocation over-diverse biomes: A global synthesis. Global Ecol Conserv 2019, 18, e00606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.; Aliyu, R.E.; Danazumi, I.B.; Indabo, S.S.; Mijinyawa, A. Colchicine-induced genetic variations in M2 generation of two soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) varieties. ABU SPGS Biennial Conf 2018, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayalakshmi, A.; Singh, A. Effect of colchicine on cluster bean [Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub.]. Asian J Environ Sci. 2011, 6, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, T.; Ologundudu, A.F.; Azuh, V.; Daramola, O.F.; Kajogbola, A. Colchicine-induced genetic variation in M2 and M3 generation of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp). Jordan J Agric Sci. 2017, 13, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, V.E.; Pegoraro, C.; Busanello, C.; Costa de Oliveira, A. Mutagenesis in rice: The basis for breeding a new super plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.; Laskar, R.A.; Wani, M.R.; Jan, B.L.; Ali, S.; Khan, S. Gamma rays and sodium azide induced genetic variability in high-yielding and biofortified mutant lines in Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.]. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 911049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udensi, O.U.; Ikpeme, E.V.; Emeagi, L.I. Flow cytometry determination of ploidy level in winded bean [Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC] and its response to colchicine-induced mutagenesis. Global J Pure Appl Sci. 2017, 23, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikani, V.O.; Adelanwa, M.A.; Aliyu, R.E. Effect of colchicine on some agro-morphophysiological traits of Phaseolus lunatus (L.) at M1 and M2 generation. Int J Appl Biol Sci Res. 2017, 8, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Esho, K.B. Study polyploidy chromosomes in faba bean by using colchicine. Global J Adv Engineer Technol Sci. 2019, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Sita, K.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Kumar, R.; Bhogireddy, S.; Varshney, R.K.; HanumanthaRao, B.; Nair, R.M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Nayyar, H. Drought or/and heat-stress effects on seed filling in food crops: Impacts on functional biochemistry, seed yields, and nutritional quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Luth, D.; Bai, G.; Wang, K.; Chen, R. Increasing seed size and quality by manipulating BIG SEEDS1 in legume species. PNAS. 2016, 113, 12414–12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, R.; Rane, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Mamrutha, H.M.; Tiwari, R. Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with grain filling duration and grain number under terminal heat stress in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Breed. 2016, 135, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukri, H.; Hejjaoui, K.; El-Baouchi, A.; El haddad, N.; Smouni, A.; Maalouf, F.; Thavarajah, D.; Kumar, S. Heat and drought stress impact on phenology, grain yield, and nutritional quality of lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus). Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 596307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, D.R.; Heckathorn, S.A.; Jayawardena, D.M.; Mishra, S.; Boldt, J.K. Effects of drought on nutrient uptake and the levels of nutrient-uptake proteins in roots of drought-sensitive and-tolerant grasses. Plants 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadayyon, A.; Nikneshan, P.; Pessarakli, M. Effects of drought stress on concentration of macro-and micro-nutrients in castor (Ricinus communis L.) plant. J Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Veneklaas, E.; Polania, J.; Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Merchant, A. Field drought conditions impact yield but not nutritional quality of the seed in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0217099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losa, A.; Vorster, J.; Cominelli, E.; Sparvoli, F.; Paolo, D.; Sala, T.; Ferrari, M.; Carbonaro, M.; Marconi, S.; Camilli, E.; Reboul, E. Drought, and heat affect common bean minerals and human diet-What we know and where to go. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Maaty, N.A.F.; Oraby, H.A.S. Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from different plant orders applying a modified CTAB-based method. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2019, 43, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, A.; Storch, M.; Baldwin, G.; Ellis, T. Bricks and blueprints: methods and standards for DNA assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzbergova, Z. Colchicine application significantly affects plant performance in the second generation of synthetic polyploids and its effects vary between populations. Ann Bot 2017, 120, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Oustric, J.; Santini, J.; Morillon, R. Synthetic polyploidy in grafted crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 540894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaynor, M.L.; Lim-Hing, S.; Mason, C.M. Impact of genome duplication on secondary metabolite composition in non-cultivated species: a systematic meta-analysis. Ann Bot 2020, 126, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.A.; Soltis, D.E. Factors promoting polyploid persistence and diversification and limiting diploid speciation during the K-Pg interlude. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2018, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Ma, Z.; Mao, H. Duplicate genes contribute to variability in abiotic stress resistance in allopolyploid wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawall, K. Genome-wide Camelina sativa with a unique fatty acid content and its potential impact on ecosystems. Environ Sci Eur 2021, 33, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Verma. R.C. High frequency production of colchicine induced autotetraploid in faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Cytologia. 2004, 69, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).