Submitted:

20 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. PICO Question and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

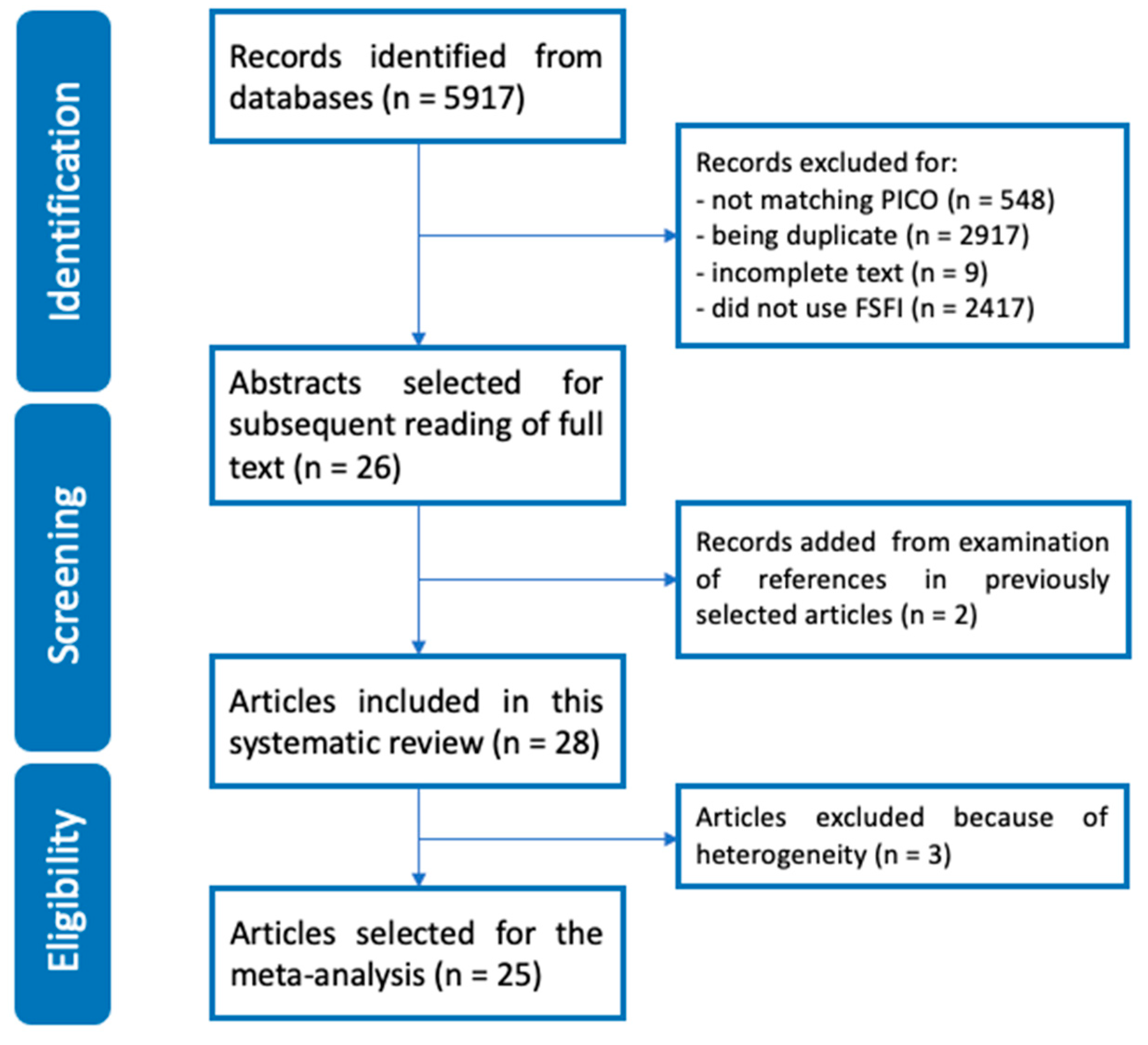

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment and Overall Quality of Included Studies in this Systematic Review (n = 28)

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Overall FSFI and subdomains scores of Included Studies in this Systematic Review (n = 28)

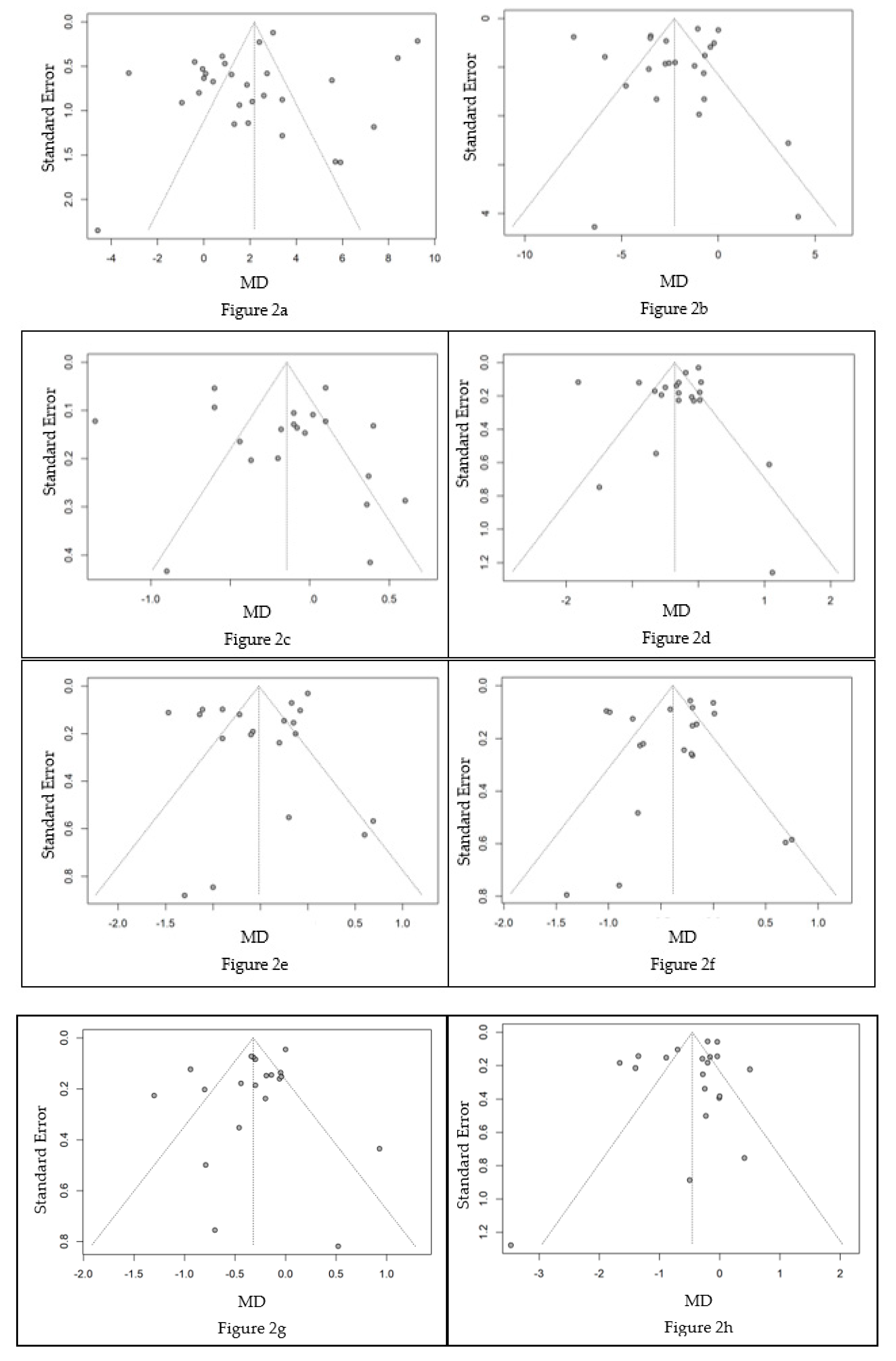

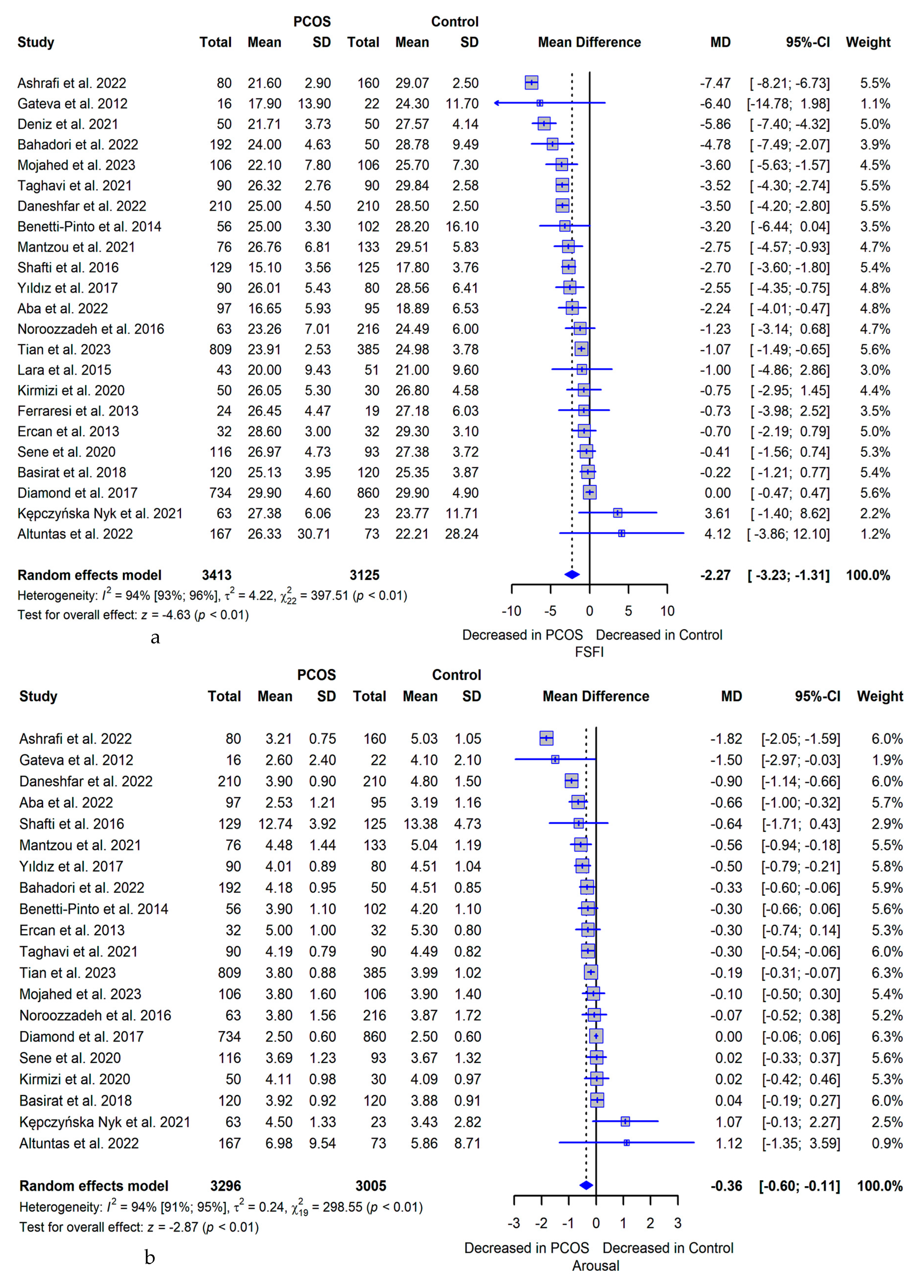

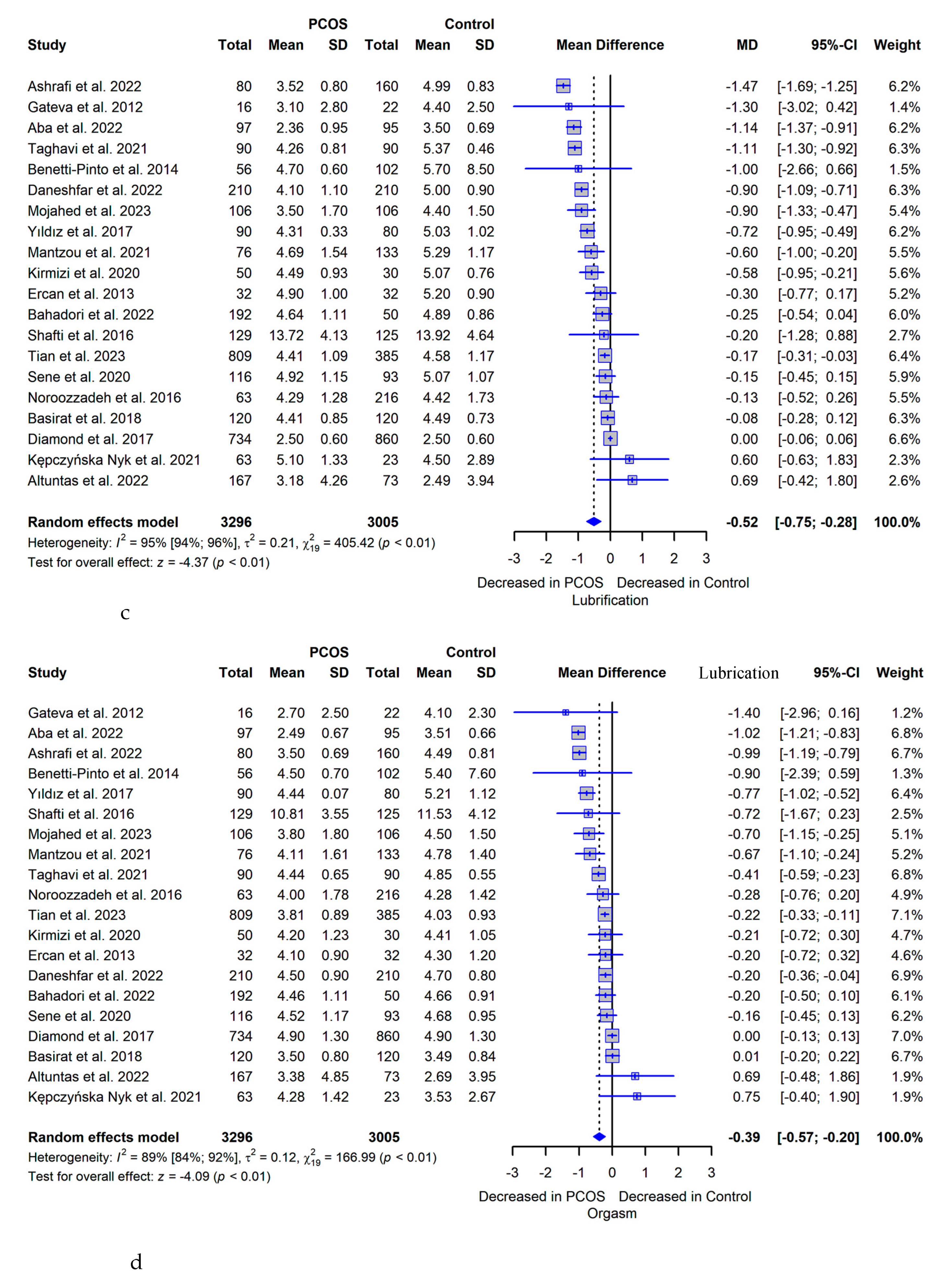

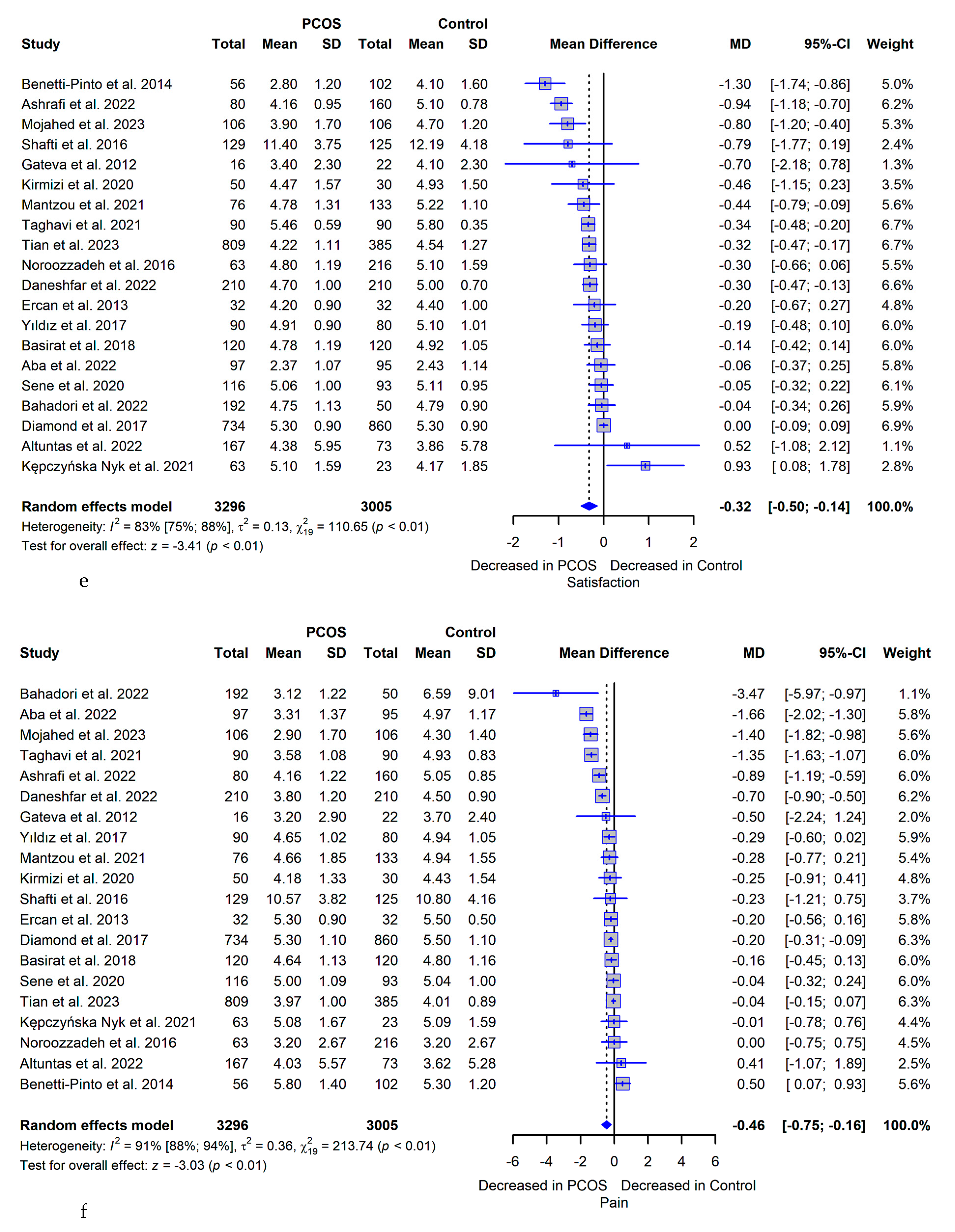

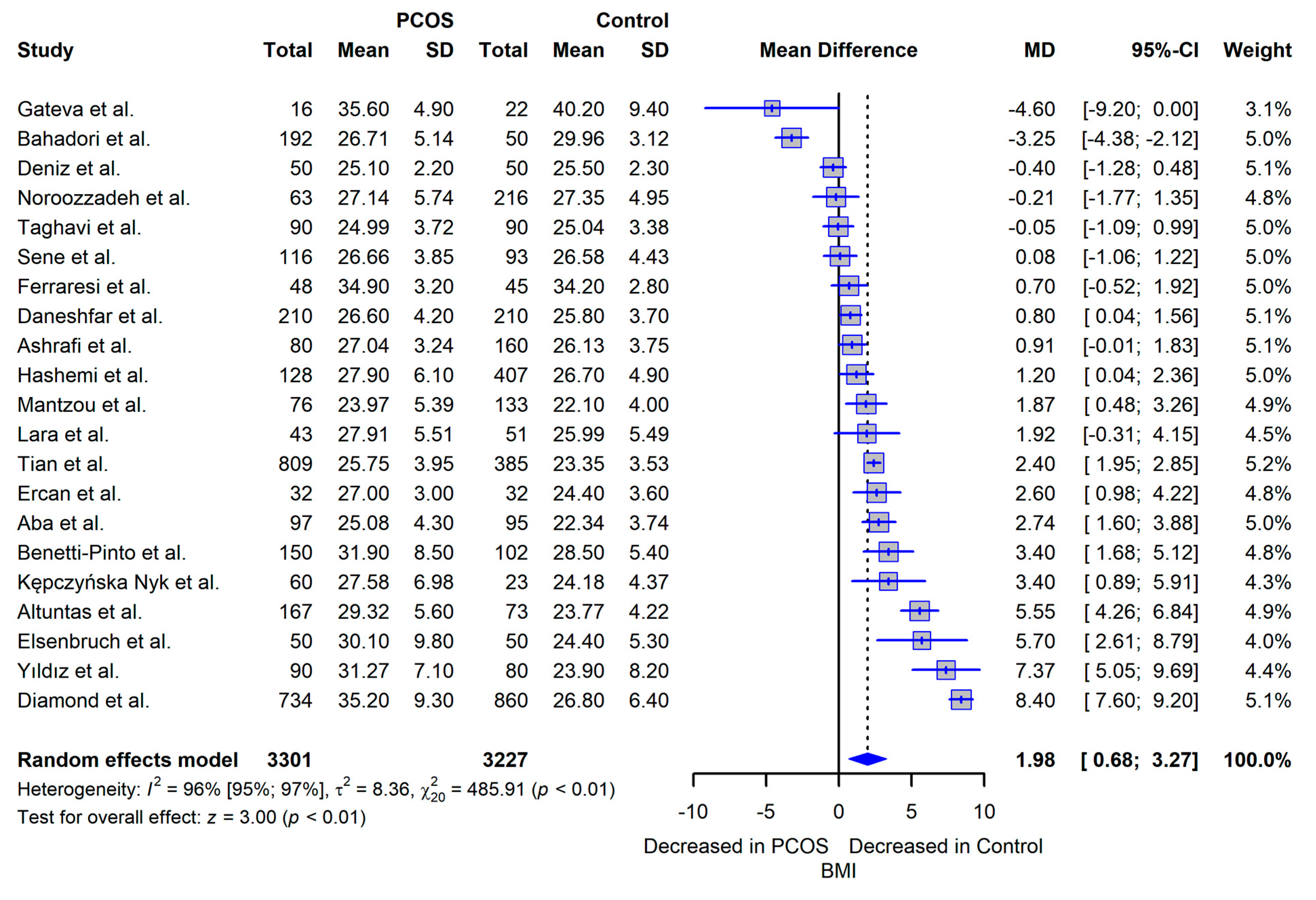

3.5. Meta-analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rotterdam, E.A.-S.P.C.W.G. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004, 81, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baracat, E.C.; Baracat, M.C.P.; Jose, M.S., Jr. Are there new insights for the definition of PCOS? Gynecol Endocrinol 2022, 38, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-I.; Liou, T.-H.; Chou, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-S. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome in Taiwanese Chinese women: comparison between Rotterdam 2003 and NIH 1990. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 88, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; E Laven, J.J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; A Boyle, J.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 189, G43–G64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti-Pinto, C.L.; Ferreira, S.R.; Antunes, A., Jr.; Yela, D.A. The influence of body weight on sexual function and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015, 291, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daescu, A.C.; et al. Effects of Hormonal Profile, Weight, and Body Image on Sexual Function in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, R.A.; Granger, L.R.; Paul, W.L.; Goebelsmann, U.; Mishell, D.R. Psychological stress and increases in urinary norepinephrine metabolites, platelet serotonin, and adrenal androgens in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1983, 145, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogure, G.S.; Ribeiro, V.B.; Lopes, I.P.; Furtado, C.L.M.; Kodato, S.; de Sá, M.F.S.; Ferriani, R.A.; Lara, L.A.d.S.; dos Reis, R.M. Body image and its relationships with sexual functioning, anxiety, and depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene, A.A.; Tahmasbi, B.; Keypour, F.; Zamanian, H.; Golbabaei, F.; Amini-Tehrani, M. Differences in and Correlates of Sexual Function in Infertile Women with and without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility 2021, 15, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Ruan, X.; Du, J.; Cheng, J.; Ju, R.; Mueck, A.O. Sexual function in Chinese women with different clinical phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2023, 39, 2221736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi, A.; Rellini, A.; Pfaus, J.G.; Bitzer, J.; Laan, E.; Jannini, E.A.; Fugl-Meyer, A.R. Questionnaires for Assessment of Female Sexual Dysfunction: A Review and Proposal for a Standardized Screener. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 2681–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, A.B.; Bruno, R.V.; de Avila, M.A.P.; Nardi, A.E. Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical and hormonal correlations. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, M.; Norström, K.; Holte, J.; Landin-Wilhelmsen, K.; Dahlgren, E.; Landén, M. Sexuality and psychological wellbeing in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with healthy controls. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 155, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsenbruch, S.; Hahn, S.; Kowalsky, D.; Öffner, A.H.; Schedlowski, M.; Mann, K.; Janssen, O.E. Quality of Life, Psychosocial Well-Being, and Sexual Satisfaction in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 5801–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellini, A.; Stratton, N.; Tonani, S.; Santamaria, V.; Brambilla, E.; Nappi, R. Differences in sexual desire between women with clinical versus biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Horm. Behav. 2013, 63, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelo-Branco, C.; Naumova, I. Quality of life and sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive review. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegner, M.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Krupp, K.; Brunner, F. Sexual Function and Socio-Sexual Difficulties in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkd. 2019, 79, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thannickal, A.; Brutocao, C.; Alsawas, M.; Morrow, A.; Zaiem, F.; Murad, M.H.; Chattha, A.J. Eating, sleeping and sexual function disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 92, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.; Loh, H.S.; Kanagasundram, S.; Francis, B.; Lim, L.-L. Sexual dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hormones 2020, 19, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q.; Luo, L.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhao, Z. Is polycystic ovary syndrome associated with risk of female sexual dysfunction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 38, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastoor, H.; Timman, R.; de Klerk, C.; Bramer, W.M.; Laan, E.T.; Laven, J.S. Sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2018, 37, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgel, A.C.F.; Simões, R.S.; Maciel, G.A.R.; Soares, J.M.; Baracat, E.C. Sexual Dysfunction in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basirat, Z.; Faramarzi, M.; Esmaelzadeh, S.; Firoozjai, S.A.; Mahouti, T.; Geraili, Z. Stress, Depression, Sexual Function, and Alexithymia in Infertile Females with and without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Int J Fertil Steril 2019, 13, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, F.; Sadatmahalleh, S.J.; Montazeri, A.; Nasiri, M. Sexuality and psychological well-being in different polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes compared with healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Heal. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzou, D.; Stamou, M.I.; Armeni, A.K.; Roupas, N.D.; Assimakopoulos, K.; Adonakis, G.; Georgopoulos, N.A.; Markantes, G.K. Impaired Sexual Function in Young Women with PCOS: The Detrimental Effect of Anovulation. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1872–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Jahangiri, N.; Sadatmahalleh, S.J.; Mirzaei, N.; Hesari, N.G.; Rostami, F.; Mousavi, S.S.; Zeinaloo, M. Does prevalence of sexual dysfunction differ among the most common causes of infertility? A cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Heal. 2022, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, A.; Kehribar, D. Evaluation of sexual functions in infertile Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Niger. J. Clin. Pr. 2020, 23, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojahed, B.S.; Ghajarzadeh, M.; Khammar, R.; Shahraki, Z. Depression, sexual function and sexual quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and healthy subjects. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Tehrani, F.R.; Farahmand, M.; Khomami, M.B. Association of PCOS and Its Clinical Signs with Sexual Function among Iranian Women Affected by PCOS. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2508–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, J.T.; Brown, A.J.; Amundsen, C.L. Sexual Dysfunction in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Effects of Testosterone, Obesity, and Depression. J. Pelvic Med. Surg. 2007, 13, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhar, T.; Sohrabvand, F.; Zabandan, N.; Shariat, M.; Haghollahi, F.; Ghahghaei-Nezamabadi, A. Sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and its affected domains. Iran J Reprod Med 2014, 12, 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Dashti, S.; A Latiff, L.; Hamid, H.A.; Sani, S.M.; Akhtari-Zavare, M.; Abu Bakar, A.S.; Sabri, N.A.I.B.; Ismail, M.; Esfehani, A.J. Sexual Dysfunction in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 3747–51. [Google Scholar]

- Aba, Y.A.; Şik, B.A. Body image and sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2022, 68, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshfar, Z.; Sadatmahalleh, S.J.; Jahangiri, N. Comparison of sexual function in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. (IJRM) 2022, 20, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.-A.; Aramesh, S.; Azizi-Kutenaee, M.; Allan, H.; Safarzadeh, T.; Taheri, M.; Salari, S.; Khashavi, Z.; Bazarganipour, F. The influence of infertility on sexual and marital satisfaction in Iranian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2021, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępczyńska-Nyk, A.; Kuryłowicz, A.; Nowak, A.; Bednarczuk, T.; Ambroziak, U. Sexual function in women with androgen excess disorders: classic forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, C.M.; Coksuer, H.; Aydogan, U.; Alanbay, I.; Keskin, U.; E Karasahin, K.; Baser, I. Sexual dysfunction assessment and hormonal correlations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2013, 25, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraresi, S.R.; Lara, L.A.d.S.; Reis, R.M.; Silva, A.C.J.d.S.R.e. Changes in Sexual Function among Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, L.A.S.; Ramos, F.K.P.; Kogure, G.S.; Costa, R.S.; de Sá, M.F.S.; Ferriani, R.A.; dos Reis, R.M. Impact of Physical Resistance Training on the Sexual Function of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1584–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafti, V.; Shahbazi, S. Comparing Sexual Function and Quality of Life in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Healthy Women. J Family Reprod Health 2016, 10, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diamond, M.P.; Legro, R.S.; Coutifaris, C.; Alvero, R.; Robinson, R.D.; Casson, P.A.; Christman, G.M.; Huang, H.; Hansen, K.R.; Baker, V.; et al. Sexual function in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome and unexplained infertility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 191–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noroozzadeh, M.; Tehrani, F.R.; Mobarakabadi, S.S.; Farahmand, M.; Dovom, M.R. Sexual function and hormonal profiles in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based study. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2017, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntaş, S. .; Çelik,.; Özer,.; Çolak, S. Depression, anxiety, body image scores, and sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome according to phenotypes. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2022, 38, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gateva, A. and Z. Kamenov. Sexual function in bulgarian patients with PCOS and/or obesity before and after metformin treatment. in JOURNAL OF SEXUAL MEDICINE. 2011. WILEY-BLACKWELL COMMERCE PLACE, 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN 02148, MA USA.

- Aydogan Kirmizi, D.; et al. Sexual function and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: Is it associated with inflammation and neuromodulators? Neuropeptides 2020, 84, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, A.; Dogan, O. Sexual dysfunction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Kocaeli Medical Journal 2017, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Naumova, I.; Castelo-Branco, C.; Casals, G. Psychological Issues and Sexual Function in Women with Different Infertility Causes: Focus on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2830–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, G.; Antes, G.; Schumacher, M. A test for publication bias in meta-analysis with sparse binary data. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, S.; Zhao, X.; Steele, R.; Thombs, B.D.; Benedetti, A.; Levis, B.; Riehm, K.E.; Saadat, N.; Levis, A.W.; Azar, M.; et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from commonly reported quantiles in meta-analysis. Stat. Methods Med Res. 2020, 29, 2520–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.S.; Roe, A.H.; Allison, K.C.; Dodson, W.C.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Kunselman, A.R.; Stetter, C.M.; Williams, N.I.; Gnatuk, C.L.; Estes, S.J.; et al. Lifestyle modifications alone or combined with hormonal contraceptives improve sexual dysfunction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokras, A.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Yildiz, B.O.; Li, R.; Ottey, S.; Shah, D.; Epperson, N.; Teede, H. Androgen Excess- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society: position statement on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and eating disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, M.; Ashraf, F.; Wajid, A. Sexual functioning as predictor of depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in females with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Pak. J. Med Sci. 2020, 36, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Ji, Y.; Chan, C.L.W.; Chan, C.H.Y. The mental health of women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2021, 24, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokras, A. Mood and anxiety disorders in women with PCOS. Steroids 2012, 77, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidooni, B.; Jenabi, E.; Khazaei, S.; Abdoli, S. The Effective Factors on The Sexual Function of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Fertil Steril 2022, 16, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E.; Lobo, R.A. Comparing Lean and Obese PCOS in Different PCOS Phenotypes: Evidence That the Body Weight Is More Important than the Rotterdam Phenotype in Influencing the Metabolic Status. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Medical Subject Headings |

|---|---|

| Pubmed/ Medline | (Ovary Syndrome, Polycystic OR Syndrome, Polycystic Ovary OR Stein-Leventhal Syndrome OR Sclerocystic Ovarian Degeneration OR Ovarian Degeneration, Sclerocystic OR Ovarian Degeneration, Sclerocystic OR Polycystic Ovary Syndrome OR Sclerocystic Ovary Syndrome OR Sclerocystic Ovaries) AND (Behavior, Sexual OR Sexual Activities OR Sexual Activity OR Sex Behavior OR Physiological Sexual Dysfunction OR Physiological Sexual Dysfunctions OR Sex Disorders OR Physiological Sexual Disorders) |

| Embase | (Polycystic ovary syndrome OR polycystic ovary disease) AND (sexuality OR sexual behavior) |

| Lilacs | [tw:(polycystic ovary syndrome)] AND [tw:(sexuality)] |

| Cinahl | (Polycystic ovary syndrome AND Sexual Dysfunction) OR (Polycystic ovary syndrome AND Sexual Function) |

| PsycINFO | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome AND (Behavior, Sexual OR Sexual Activities OR Sexual Activity OR Sex Behavior OR Physiological Sexual Dysfunction OR Physiological Sexual Dysfunctions OR Sex Disorders OR Physiological Sexual Disorders) |

| Google Scholar | (Polycystic ovary syndrome AND Sexual Dysfunction) OR (Polycystic ovary syndrome AND Sexual Function) |

| Cochrane | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome AND Sex Behavior |

| Author/ Year/ Country | Study Design | Sample size per group (n) | Mean age ± SD | BMI ± SD | Total FSFI Comparison: PCOS Group vs. Control | Total FSFI p-value | Affected FSFI Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benetti-Pinto et al 2014 Brazil [5] |

Case control | PCOS: 150 Control: 102 |

PCOS: 26.9 ± 4.9 Control: 35.6 ± 7.3 |

PCOS: 31.9 ± 8.5 Control: 28.5 ± 5.4 |

Lower in PCOS | p = 0.005 | Arousal, lubrication, satisfaction and pain |

| Basirat et al 2019 Iran [25] |

Case control | PCOS: 120 Control: 120 |

PCOS: 29.55 ± 5.17 Control: 29.33 ± 6.23 |

PCOS: 39.5 ± 15.81 Control: 45.5 ± 5.48 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | None |

| Bahadori et al 2022 Iran [26] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 192 Control: 50 |

PCOS: 31.17 ± 6.57 Control: 34.18 ± 4.13 |

PCOS: 26.71 ± 5.14 Control: 26.96 ± 3.12 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Arousal, lubrication and pain |

| Mantzou et al 2021 Greece [27] |

Case control | PCOS: 76 Control: 133 |

PCOS: 22.17 ± 2.51 Control: 21.62 ± 1.93 |

PCOS: 23.97 ± 5.39 Control: 22.1 ± 4 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.001 | Arousal, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

| Ashrafi et al 2022 Iran [28] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 80 Control: 160 |

PCOS: 31.94 ± 4.44 Control: 31.66 ± 1.89 |

PCOS: 27.04 ± 3.24 Control: 26.13 ± 3.75 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.001 | Desire, arousal, pain, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

| Deniz et al 2020 Turkey [29] |

Case control | PCOS: 50 Control: 50 |

PCOS: 32 ± 4 Control: 31 ± 4 |

PCOS: 25.1 ± 2.2 Control: 25.5 ± 2.3 |

Lower in PCOS | p = 0.001 | Desire, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain |

| Tian et al 2023 Germania [10] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 809 Control: 385 |

PCOS: 27.25 ± 3.98 Control: 27.56 ± 3.83 |

PCOS: 25.75 ± 3.95 Control: 23.35 ± 3.53 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Desire, orgasm, lubrication and satisfaction |

| Mojahed et al 2023 Iran [30] |

Case control | PCOS: 106 Control: 106 |

PCOS: 26.9 ± 5.2 Control: 27.8 ± 6.8 |

N.A. | Lower in PCOS | p < 0.001 | Arousal, pain, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

| Hashemi et al 2014 Iran [31] |

Case control | PCOS: 128 Control: 407 |

PCOS: 30.6 ± 5.01 Control: 29.4 ± 5.8 |

PCOS: 26.7 ± 4.9 Control: 27.9 ± 6.1 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Satisfaction, orgasm, lubrication and arousal |

| Anger et al 2007 USA [32] | Case control | PCOS: 33 | PCOS: 36 ± N.A. | N.A. | Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Arousal and lubrication |

| Eftekhar et al 2014 Iran [33] | Case control | PCOS: 130 | PCOS: 27.02 ± 4.27 | N.A. | Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | None |

| Dashti et al 2016 Malasya[34] | Cross sectional | PCOS: 16 | PCOS: 33.44 ± 5.88 | PCOS: 28.04 ± 3.34 | Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Arousal and lubrication |

| Aba et al 2022 Turkey [35] |

Case control | PCOS: 97 Control: 95 |

PCOS: 28.23 ± 4.56 Control: 29.33 ± 5.61 |

PCOS: 25.08 ± 4.3 Control: 22.34 ± 3.74 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Desire, arousal, pain, lubrication and orgasm |

| Daneshfar et al 2022 Iran [36] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 210 Control: 210 |

PCOS: 30 ± 5.3 Control: 31.4 ± 2.7 |

PCOS: 26.6 ± 4.2 Control: 25.8 ± 3.7 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.001 | Desire, arousal, pain, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

| Taghavi et al 2021 Iran [37] |

Case control | PCOS: 90 Control: 90 |

PCOS: 28.8 ± 4.39 Control: 30 ± 4.83 |

PCOS: 24.99 ± 3.72 Control: 25.04 ± 3.38 |

Lower in PCOS | p < 0.05 | Desire, arousal, pain, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

| Kępczyńska-Nyk et al 2021 Poland [38] | Case control | PCOS: 60 Control: 23 |

PCOS: 26.56 ± 5.45 Control: 30.85 ± 6.73 |

PCOS: 27.58 ± 6.98 Control: 24.18 ± 4.37 |

Higher in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Satisfaction |

| Ercan et al 2013 Turkey [39] |

Case control | PCOS: 32 Control: 32 |

PCOS: 27.4 ± 3.3 Control: 27 ± 3 |

PCOS: 24.4 ± 3.6 Control: 27 ± 3 |

PCOS similar to controls | p > 0.05 | None |

| Ferraresi et al 2013 Brazil [40] |

Case control | PCOS: 48 Control: 45 |

PCOS: 26.1 ± 1.05 Control: 31.1 ± 1.02 |

PCOS: 34.2 ± 2.8 Control: 34.9 ± 3.2 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | N.A. |

| Lara et al 2015 Brazil [41] |

Case control | PCOS: 43 Control: 51 |

PCOS: 27.8 ± 5.34 Control: 29.74 ± 5.26 |

PCOS: 27.91 ± 5.51 Control: 25.99 ± 5.49 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Pain, lubrication and arousal |

| Shafti et al 2016 Iran [42] |

Casual comparative study | PCOS: 129 Control: 125 |

PCOS: 30.10 ± N.A. Control: 32.79 ± N.A. |

N.A. | PCOS similar to controls | p > 0.05 | None |

| Diamond et al 2017 Georgia [43] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 734 Control: 860 |

PCOS: 95.1 ± 26.3 Control: 72.4 ± 18.5 |

PCOS: 35.2 ± 9.3 Control: 26.8 ± 6.4 |

PCOS similar to controls | p > 0.05 | Arousal and satisfaction |

| Noroozzadeh et al 2017 Iran [44] |

Case control | PCOS: 63 Control: 216 |

PCOS: 33.6 ± 7.2 Control: 36.3 ± 6.9 |

PCOS: 27.14 ± 5.74 Control: 27.35 ± 4.95 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Orgasm and satisfaction |

| Sene et al 2021 Iran [9] |

Case control | PCOS: 116 Control: 93 |

PCOS: 32 ± 5 Control: 34 ± 6 |

PCOS: 26.66 ± 3.85 Control: 26.58 ± 4.43 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Orgasm |

| Altuntas et al 2022 Turkey [45] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 167 Control: 73 |

PCOS: 25.87 ± 5.64 Control: 27.25 ± 5.85 |

PCOS: 29.32 ± 5.6 Control: 23.77 ± 4.22 |

Higher in PCOS | p > 0.05 | None |

| Gateva et al 2012 Bulgaria [46] |

Case control | PCOS: 16 Control: 22 |

PCOS: 32.5 ± 8.5 Control: 32.5 ± 8.5 |

PCOS: 35.6 ± 4.9 Control: 40.2 ± 9.4 |

Lower in lean PCOS than obese PCOS |

p > 0.05 | Arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain |

| Kirmizi et al 2020 Turkey [47] |

Case control | PCOS: 50 Control: 30 |

PCOS: 25.1 ± 4.4 Control: 31.9 ± 4.73 |

PCOS: 26.4 ± 5.22 Control: 25.08 ± 4.84 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Lubrication |

| Yıldız et al 2017 Turkey [48] |

Cross sectional | PCOS: 90 Control: 80 |

PCOS: 28.3 ± 2.12 Control: 29.1 ± 4.8 |

PCOS: 31.27 ± 7.1 Control: 23.9 ± 8.2 |

Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Orgasm |

| Naumova et al 2021 Spain [49] |

Case control | PCOS: 37 Control: 67 |

N.A. | N.A. | Lower in PCOS | p > 0.05 | Desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).