1. Introduction

In the second half of the twentieth century, individual and/or private means of transport gained an ever-growing popularity within high income countries, leading to a decrease in the use of public transport. The consequences in terms of traffic congestion, CO

2 emission and public health brought out the need to foster a decrease in the use of private cars and a wider use of public transport. On the one hand, such a change in mobility habits involves the social and economic dimension, indeed, car ownership has become an indicator of a population’s standard of living in recent years [

1]. Nevertheless, on the other hand, there is a genuinely psychological dimension to consider in order to understand mobility choices and the use of private vs. public means of transport. The reasons underlying the choice of a certain way of transport are manifold and related to an individual’s need, meanings, values and motivations [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, to promote the transition from private cars to public transport, it is crucial to comprehend the factors influencing individuals’ mobility choices.

Plenty of research concerning the use and satisfaction with public transport has firstly highlighted that the wide use of private cars originates from the imbalance between the demands and needs of people’s mobility and the supply of public transport [

7,

8]. Moreover, the choice to use private car is strengthened by several advantages in terms of independence and freedom in schedules and itinerary. It is also based on cultural and psychological reasons, since cars represent much more than a mean of transport [

9,

10]. Finally, the physical characteristics of the territory are a key variable in the choice of the mean of transport [

11]

In large cities and urban areas, public transport is more widely used due to its ability to meet the needs of users, while, in contrast, traveling by car often means spending a long time to cover even short distances [

12,

13]. On the contrary, in country and in suburban areas consisting of small and medium-sized inhabited centres, connected to each other by suburban roads, the gap between the demand for mobility and the supply of public transport widens. In such areas services and workplaces can be reached only by private cars [

7,

8,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In these areas, public transport is primarily used by individuals who do not own a private car, including students, the elderly, and people with lower incomes [

8,

10,

18,

19]. Public transport is an essential service for these people, ensuring their mobility and access to remote services. Indeed, social-demographic characteristics cover an important role in the choice of public transport as well. Specifically, age defines the different needs and the different mobility possibilities of an individual in the different periods of life [

20,

21,

22]. University students, for example, are likely more flexible in the choice of public transports they use, contrarily to other categories of transport users [

23,

24].

In order to promote sustainability, it is necessary to promote and support the use of public transport even for those who own and prefer to use private cars, acting on the factors which may promote people’s behavioural change towards the use of LPT. It’s necessary to take into consideration the characteristics of the service provided as a response to the users’ needs with the aim in order to provide a service that is up to the mobility needs and expectations of potential users [

8,

18,

25,

26,

27]. Possible changes in public transport service should aim to overcome any resistance rooted in the lack of appeal of public transport compared to private cars [

27].

Various characteristics of the service offered by public transport are highlighted in literature as key variables in the choice to use it [

26,

28]. Furthermore, the influence of the passengers’ experience on satisfaction with the service and its use has been widely underlined [

29,

30,

31,

32]. User experience encompasses both cognitive evaluation and emotional aspects. Users and potential users of public transport have a subjective experience of the service that originates from any contact, both direct one (use of the service) and indirect (news, advertisement, vicarious experience, word of mouth, etc.) that affects the user’s representation of the service at different levels [

33,

34,

35]. In Italy, in the collective imagination public transport is scarcely appreciated and is often associated with disservices, malfunctions and unreliability [

25].

From the analysis of the services’ features that more widely affects the satisfaction with the service and the choice to use the LPT, different dimensions and factors emerged. A previous study conducted [

36] detected 4 dimensions linked to the satisfaction starting from the analysis of 17 different factors. Those dimensions are system, comfort, staff, and safety. Results are not consistent since some differences emerged in relation to the city in which data were collected. Such evidence proves that public transport services are felt differently according to the local reality and to the urban context. Indeed, there are several factors determining such variation in travellers’ perceptions, including factors related to the management (how those services were supplied) and personal values (culture and tradition).

Considering the wider literature, the choice of LPT is firstly and strictly related to the accessibility of the service, that is to say the possibility of easily reach public transport stops [

28,

37,

38,

39]. Secondly, people’s choices are affected by the conditions of operation, more specifically: time schedule, rides frequencies, reliability of the service and compliance with the scheduled travel times [

26,

40,

41]. The time involved in travelling is a crucial factor to determine the choice of the public transport as well [

28,

42,

43]. Satisfaction with the use of public transport also depends on comfort, vehicle’s modernity and cleanness, staff behaviour [

26,

44]. However, results are prone to variations in relation to the type of transport analysed. For example, vehicle’s cleanness and staff behaviour are considered more relevant by subway users. In the case of bus travellers, regularity of the service, coverage extension and vehicle’s cleanness were detected as the most important features [

26]. In terms of economic aspects, the ticket cost is an important feature which can operate a negative impact on travellers’ satisfaction [

45].

This broad set of factors contributes to creating a subjective travel experience of a multidimensional nature. Specifically, travel experience includes a cognitive component, related to the judgement of the quality and value of the service including (in the case of public transport) costs, duration of the travel and punctuality [

46]. However, the cognitive aspect is not the only relevant one. For example, experiences related to bus services, rely on numerous affective factors and non-instrumental factors as well, like cleanliness, privacy, safety, comfort, distress, social interaction, and scenarios [

47]. For these reasons, the assessment of travel experience and the aspects that must be included in this assessment are a debated issue [

33,

48]. Among the most widespread measures to assess this experience, the Satisfaction with Travel Scale was designed to measure the quality of the travel experience in terms of the global experience of the service, consistently with the holistic nature of the construct; furthermore, it integrates the assessment of both features of the service and characteristics of the offer, covering not only the cognitive dimension but also the affective one [

31]. More specifically, the measure combines cognitive appraisals (related to the quality of the service) with affective appraisal, which have been divided into two subdimensions: the first one focused on positive arousal (for example: enthusiasm, boredom) and the second one focused on positive deactivation (excitement-relaxation). Such measure was designed in order to investigates travel wellbeing, a subjective psychological dimension that literature stressed as related to the wider personal wellbeing [

49,

51]. Satisfaction with the travel experience motivates the use of public transport; in fact, the more satisfied travellers are with their public transport experiences, the more likely they are to use it again in the future [

52]. Furthermore, the most closely related factors for satisfaction with travel experience (e.g.: regularity of the service and coverage extension…), were described among the main reasons to use or not to use the TP [

40,

26,

28,

40,

41].

Among psychological factors affecting the choice of the LTP use, personal values play a role as well. So, the concerns with ecological matters and the great importance assigned to sustainability could influence mobility choices, even if the balance between behavioural and economical costs and benefits is often the main criteria. In the opinion of a sample of university students living in the North of Italy [

53], sustainability emerged as the second factors that most influence the choice to use public transport, after comfort (other factors considered were the length of the journey and traffic congestion) regardless of the service availability. Moreover, a previous study concerning the use of LTP, showed that people concerned with environmental problems were more prone to use TPL when they experience a change of context (e.g., a transfer) so proving that it is possible to change one’s travel habits [

5]. Quite the opposite, it was underlined that, when the use of private car is a consolidated habit, it is more difficult that the concern for the environment could determine to shift travel choices to LPT; it is easier for people to resolve the cognitive dissonance between their behaviour (using a means of transport harmful for the environment) and their attitude (recognizing the importance of acting sustainable behaviour) by modifying the latter [

54].

Considering the above, to foster the use of LPT it is necessary to detect the factors underlying travel behaviours, for political strategies will be more efficient if they are oriented to the antecedents of the behaviour. The literature has primarily examined the factors influencing satisfaction with one’s mode of travel; however, to our knowledge, there have been few studies that have specifically focused on the reasons for using or not using LPT. In particular, the different reasons for use or non-use of the LTP have not yet been specifically investigated enough with reference to both the specific modes of transport and the different categories of transport users, in relation to their specific travel needs. Furthermore, the possible influence of the importance assigned by users and potential users of LPT to the goal of sustainability on the choice of the mean of transport deserves further investigation, compared to other factors that are known to affect mobility choices. Consistently with the need to deepen the understanding of the factors affecting the choice to use LPT, the present study investigates the reason for use or non-use of LPT, the users’ experience and subjective perception with relation to a specific public bus line. The investigated service connects a big Hospital located in a suburban area to the surrounding towns. The present study examined various categories of users’ subjective perceptions and experiences related to travel to the hospital.

1.1. The present study

The research is part of the European territorial cooperation project “SAMBA. Sustainable Mobility Behaviours in the Alpine Region” implemented by the Province of Padova (Italy) in order to promote the use of sustainable transport modes with particular reference to the use of local public transport. The study aimed to investigate the mobility experience and the reasons for use and non-use of a specific public bus line (suburban route E034/N) by the people travelling to and from the Hospital Centre in the Municipality of Monselice-Schiavonia. People who travel to the hospital belong to three categories: hospital employees, students of master’s degree in Nursing Sciences, and hospital users (patients, caregivers, visitors). A specific objective of the study is to understand how the service is evaluated and used, or not used, by these different types of travellers in relation to their different mobility needs. The large hospital complex is about 30 km from the city of Padova in a predominantly agricultural, semi-urban area, with some industrial areas and small and medium-sized towns. The local public bus services connect the towns to each other and to the hospital. However, as is generally case in rural and suburban areas [

7,

16,

17,

18,

55], the most common mode of transportation is private car ownership, which offers greater flexibility for getting around the area. The research results aimed to facilitate the implementation of appropriate measures to promote the use of the public bus service, starting from the evaluation of the service by its users and an analysis of the factors influencing their choice to use or not use LPT.

1.1.1. Objectives

Specifically, the study had the following objectives:

To investigate the travel experience on the bus route E034/N from and to the Hospital in terms of: satisfaction for several aspects of the service (accessibility, travel time, timeliness, reliability, time schedule, cost, comfort, safety and sustainability), quality of the experience (using the Satisfaction with travel scale), and relationships between the satisfaction for the bus service and the quality of the travel experience;

To examine the characteristics of the mobility to and from the hospital by non-users of LTP, along with their satisfaction with several aspects of their chosen mode of transport (accessibility, travel time, timeliness, reliability, time schedule, cost, comfort, safety and sustainability) compared to the satisfaction with LTP service;

To explore the reasons behind the decision not to use the public transport;

To investigate possible differences based on gender, age and the different categories of current and prospective bus service users including those commuting to work, students, and individuals travelling to the hospital as patients, caregivers, or visitors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and participant

People who travel to the hospital were invited to complete an anonymous on-line survey specifically developed for the research purposes. The survey instrument took approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete and included different questions for the users and non-users of LPT (local public transport). The invitation to take part in the survey was sent both to students and to the hospital employees via specific mailing list, thanks to the cooperation with the master’s degree in nursing sciences, which has its headquarters in the Hospital, and of the Hospital Managers. Moreover, the LPT company distributed a broader invitation near the hospital, aiming to reach all individuals traveling to and from the hospital, including patients, caregivers, and visitors.

Within one month, 400 fully completed questionnaires were collected out of the 599 accesses to the online questionnaire, and these were considered valid cases. A majority of respondents are women (71%) and individuals aged between 41 and 60 (55%; 14% 16-25 years old; 17% 26-40 years old, 14% over 60). The respondents were asked to define the main reason why they travel to the hospital. Most respondents indicated that their primary reason for traveling to and from the hospital was for work (56%), followed by 31% traveling as customers (patients, caregivers, or visitors), and 13% as students enrolled in the Nursing Science master’s degree program. Informed consent was obtained online before participants completed the questionnaire. They were provided with information regarding data collection, processing, and storage in accordance with privacy regulations, as well as the research objectives and compliance with ethical standards. The study was approved by the university ethics committee.

2.2. Instrument and measures

The questionnaire comprised various sections designed to explore the travel experience to and from the hospital, as well as the factors influencing the use or non-use of the LPT service. It was administered to both users and non-users of the bus line.

A first section, addressed to all participants, aimed at collecting personal data (gender and age), the reasons for travelling to the hospital (this question split the respondents’ sample into three categories of users: workers, students, and customers), the frequency of the travel, the use or non-use of the public bus service (users were considered those who happened to use the bus at least once).

The second section, intended for users of the public bus service, included a range of measures related to their experience using the service.

Travel habits: regarding travel habits, we first assessed the frequency of using LPT to travel to the hospital using a specific 4-point scale (from 0=almost never, to 3=always; 2=sometimes; 3=often), secondly, further characteristics of the journey to the hospital were investigated: the exclusive use of the bus for journeys to the hospital or the use of alternative modes of travel (car used only passenger, car shared with other passengers, bicycle, train or scooter), the reasons for the possible exclusive use of LPT (two possible answers: lack of alternative means of transport, preference for the bus even if other means of travel are available), the need to use other means above the bus to complete the ride to the hospital.

Psychological aspects influencing TPL use: to understand the psychological factors influencing LPT use, we assessed the quality of the travel experience using the Satisfaction with Travel Scale [

31]. Participants were asked to evaluate their travel experience to and from the Hospital using nine pairs of opposite adjectives (e.g.: fed-up vs. engaged, jittery vs. relaxed, worried vs. serene, ...). The sum of the scores obtained from all the answers (from a minimum of -3 to a maximum of 3 for each answer) provides the overall score of satisfaction for the travel experience. Finally, the level of satisfaction for several aspects of the service was assessed trough specifically designed questions. Participants were asked to express their satisfaction for ten different aspects of the service on a Likert scale ranking 1 to 7 (from “not at all satisfied” to “completely satisfied”). Based on the literature reviewed in the introduction, the aspects investigated emerged as the main motivations for the choice to use or non-use of the public service: services’ accessibility (ease in the reaching the stops on the LTP line), expected time spent for the travel, timeliness, reliability (being certain that the service is actually carried out in times and ways as expected), time schedule (the possibility to benefit from the service in useful times), cost, comfort (for example the availability of seats, the suitability of the means, etc.), safety and sustainability of the used mode of transport. Furthermore, in addition to those aspects, since the assessment took place during the pandemic emergence, it was chosen to also include the risk management related to the possibility of an infection by Covid-19.

The third section, directed at individuals who have never used the LPT service to travel to the hospital, aimed to explore the reasons behind their choice of alternative transport modes over the bus. First, non-users of LPT were asked whether they were aware of the specific public bus service under investigation. Additionally, those who acknowledged awareness of the service but still chose not to use it were questioned about their primary reasons for this choice. Specifically, the subjects were asked to evaluate, on a Likert scale ranking 1 to 7, how the following features of the bus service negatively impacted on the choice of using it: low accessibility, time spent for the travel, timeliness, low reliability, inadequate time schedules with relation to their needs, costs, comfort (being uncomfortable, such as few seats available, inadequate means, etc.), lack of safety and the sustainability of the used transport mode, the dissatisfaction with the management of the risk of contamination due to Covid-19. These characteristics of the service are the same that users of the LPT have assessed with respect to their level of satisfaction. Moreover, the availability of free parking nearby the hospital was added as possible reason influencing the choice not to use public transport. Finally, participants who have never used the public bus service, were asked which means of transport they travel with to reach the hospital and subsequently to evaluate the level of satisfaction with the use of this means (Likert scale ranking 1 to 7 from “not at all satisfied” to “completely satisfied”), considering the following aspects: time spent, cost, comfort, safety, autonomous schedules, sustainability, Covid-19 infection risk.

3. Results

3.1. TPL users and non users

Among the participants who completed the questionnaire, 23% (94 individuals) utilized the bus service to travel to the hospital (

Table 1). When considering differences related to gender, age, and user categories, it was observed that women use the bus service more frequently than men (χ²=4.8; p=.028). Additionally, individuals under the age of 26 (χ²=10.2; p<.001) use the bus service more frequently compared to other age groups. Notably, among the student population, there is a higher percentage of individuals who rely on the bus service (64%), in contrast to workers (among whom only 20% use the bus service) and hospital users (with only 13% utilizing the bus) (χ²=55.4; p<.001) (

Table 1).

Regarding the frequency of bus service usage, participants were asked to indicate how often they use the investigated bus line to travel to and from the hospital, using a 4-point scale ranging from "almost never" to "always." The majority of users reported sporadic use, with 46% choosing "sometimes" and 28% selecting "almost never." In contrast, 11% of users stated that they use the service "often," and 16% reported using it "always". A specific question was directed to individuals who exclusively use Local Public Transport (LPT) to travel to the hospital, aimed at understanding the reasons for this specific and exclusive reliance. Among this group, 71% cited the lack of alternative transportation as the reason for exclusively using LPT to and from the hospital. The remaining 29% preferred to use the bus even though they had other means of transportation available. Therefore, among those who use LPT, multiple modes of transportation are utilized, with the bus being just one of the options for reaching the hospital. The primary alternative means of transportation used by most individuals is the car, with 65% traveling alone and 27% carpooling. A smaller number of individuals (7) use other means of transportation, such as bicycles, trains, or scooters. Furthermore, significant differences in alternative transportation methods emerge among different categories of hospital users (χ²=25.9; p<.001). Specifically, over half of the students (53%) opt for carpooling, while about 25% of the users and a smaller percentage of workers (7%) primarily use a car alone (83%).

Among respondents who never use the bus service to travel to the hospital, the vast majority rely on private cars (97%), while a smaller number use carpooling (N=6) or bicycles (N=4).

3.2. Bus users’ satisfaction with the LPT vs satisfaction with the car use in non-users of TPL

LPT users were asked to assess their level of satisfaction with various aspects of the service, while non-users were questioned about their satisfaction with similar aspects of the mode of transportation they used to travel to the hospital (

Table 2). It should be noted that the data in

Table 2 pertains specifically to non-users who drive a car to reach the hospital (data related to bicycle users are not presented due to their low numbers, which would not allow for robust analysis). Some characteristics of the mode of transportation are unique to public transport, specifically accessibility, reliability, and punctuality. On the other hand, the ability to manage travel schedules is a common feature, but it is defined differently: as hourly coverage for LPT and as autonomous schedules for private cars. An analysis of variance was conducted to compare the level of satisfaction with common features between public transport and private cars (travel time, cost, comfort, safety, hourly coverage/autonomous schedules, sustainability, and Covid-19 infection risk) in order to identify statistically significant differences.

Regarding users’ satisfaction with various aspects of the LPT service, the results indicate that the most highly valued features of the service were sustainability, safety, punctuality, and reliability. The service’s comfort and the measures taken to minimize the risk of Covid-19 infection also received positive feedback (with mean scores exceeding 4). Conversely, the aspects that emerged as areas of concern were the time schedule and the cost of the service, followed by accessibility, particularly the ease of reaching the bus stop.

No significant differences were observed based on gender or the categories of individuals traveling to and from the hospital. However, in terms of age, a positive correlation was found between age and satisfaction with the accessibility of the service (r=.24; p<.05). This highlights that satisfaction with accessibility increases with age, suggesting that younger individuals tend to be less satisfied with the accessibility of the service. Satisfaction with other aspects of the LPT service did not exhibit variations based on the age of users.

The satisfaction level among car users (who do not use public transport) is notably high, with mean scores equal to or higher than 4.7, except for "sustainability." The most appreciated feature is the independence from time schedules, followed by comfort, travel time, perceived risk of contagion, and costs.

Some effects related to gender, age, and categories of individuals traveling to and from the hospital on satisfaction with car travel were observed. In terms of gender, a significant difference in satisfaction was found for car sustainability, with women expressing lower satisfaction compared to men (Women: M(SD)=3.84(2.01); Men: M(SD)=4.45(2.21); F=4.47; p<.035). Regarding age, negative and significant correlations were identified between age and satisfaction with independence from time schedules (r=-.14; p<.05) and the comfort of the mode of transport (r=-.15; p<.05), indicating that satisfaction levels for these aspects tend to decrease with age. In relation to the different categories of individuals traveling to and from the hospital, lower satisfaction was reported among hospital users (patients, caregivers, visitors) compared to workers and students regarding travel time (users: M(SD)=4.69(2.21); workers: M(SD)=6.01(1.54); students: M(SD)=5.50(1.41); F=13.81; p<.001) and the independence from time schedules (users: M(SD)=5.70(1.96); workers: M(SD)=6.62(1.06); students: M(SD)=6.56(.96); F=13.81; p<.001).

When comparing the satisfaction levels of LPT users and car users, it was observed that car users were more satisfied with schedules, comfort, cost, travel time, and the mitigation of the risk of Covid-19 infection. No significant difference was found in satisfaction with safety between LPT and car users (

Table 2). However, LPT users expressed higher satisfaction with the sustainability of their chosen mode of transport.

3.3. Quality of the travel experience and satisfaction in TPL users

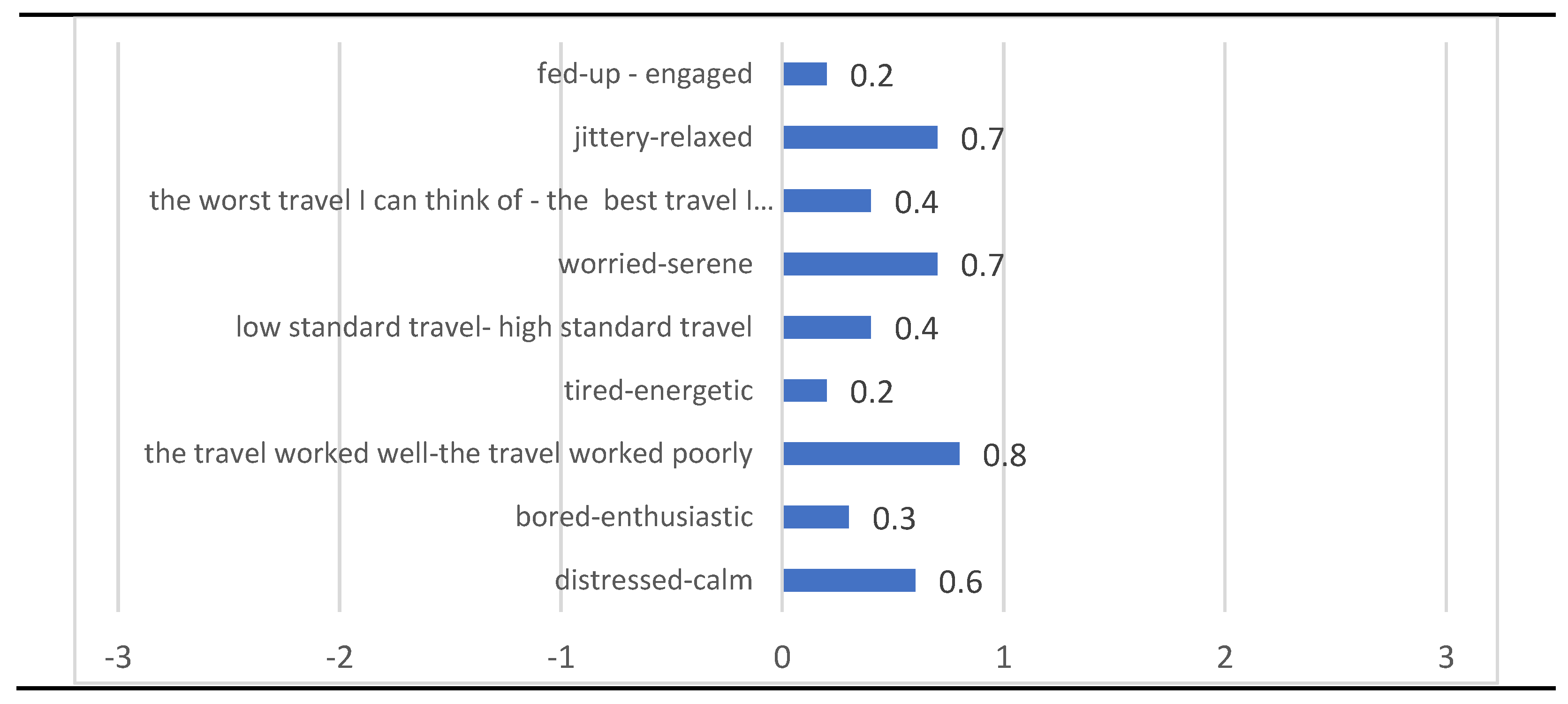

The quality of the travel experience on the LPT was evaluated using the Satisfaction with Travel Scale [

31]. The results indicate that the mean scores for each aspect related to the travel experience are positive (

Figure 1). This implies that passengers tended to choose adjectives that describe pleasant aspects of their travel experience rather than unpleasant ones. Specifically, they reported experiencing predominantly low arousal and positive emotions during the trip. They felt calm, relaxed, and at ease, perceiving that the travel experience was proceeding smoothly. Overall, the travel experience appeared to be quietly satisfying

Regarding potential variations in the perception of the travel experience based on gender and the categories of individuals traveling to and from the hospital (workers, students, customers), no statistically significant differences were identified. However, correlation analysis revealed a noteworthy connection between the perceived quality of the LPT and age. More precisely, a positive correlation was observed between age and the total score on the Satisfaction with Travel Scale (r=.23, p<.05), indicating that younger individuals tend to report a lower quality of the travel experience.

The perceived quality of the travel experience, as assessed by the Satisfaction with Travel Scale, displayed strong correlations (r values ranging from .35 to .53) with satisfaction levels for all the aspects of the LTP service under consideration. Notably, comfort, accessibility, hourly coverage, and protection from Covid-19 contagion were identified as the characteristics most closely linked to a higher quality of the travel experience. Conversely, satisfaction with the cost of the service appeared to be the least significant factor influencing the perceived quality of the travel experience.

3.4. Reasons for not using the TPL

Through the administration of the questionnaire, we investigated the primary reasons behind the decision not to use TPL (Local Public Transport). Initially, we inquired whether respondents who claimed to have never used the bus service were aware of its existence. From our data, we found that 16% of the respondents (50 individuals) were unaware of the bus service to the Hospital.

Additionally, we asked respondents who were aware of the bus service but chose not to use it about the main factors influencing their decision. In the questionnaire, we presented the same service characteristics that were used to assess TPL users’ satisfaction. Specifically, participants were asked to rate, on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, how various factors hindered their use of the bus service. These factors included low accessibility, travel time, timeliness, reliability, inadequate schedules that didn’t align with their needs, costs, comfort issues (such as insufficient seating or inadequate vehicles), safety concerns, sustainability concerns regarding the vehicles, and dissatisfaction with the management of Covid-19 infection risks. Furthermore, the availability of free parking near the hospital was also considered.

Table 4 presents the mean scores of these factors affecting the decision not to use TPL.

The results indicate that the availability of free parking near the hospital encourages the use of private cars over TPL. Additionally, irrespective of the service’s characteristics, the most influential factor in the decision not to use TPL is the inadequacy of the service’s schedule to meet users’ needs. This scheduling issue is followed by problems related to accessibility and the perception of longer travel times to reach the hospital. Concerns about the risk of Covid-19 contagion also play a significant role (M=4.04) (

Table 4). Interestingly, these reasons align with the most critical service factors (sources of lower satisfaction) identified by users (see

Table 2).

Furthermore, we examined the impact of gender, age, and the categories of people traveling to and from the hospital on the reasons for not using TPL. No differences were observed based on gender and age. However, hospital users (patients, caregivers, visitors) indicated that certain factors had a more substantial influence on their decision not to use TPL compared to students and workers. Specifically, they associated their choice not to use the bus service with service unreliability, lower timeliness, discomfort, safety concerns, lower sustainability, and the perceived risk of Covid-19 contagion (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Regarding the specific usage patterns of Local Public Transport (LPT) on Bus Line E034/N for accessing Schiavonia Hospital, the majority of individuals, especially users such as patients, visitors, caregivers, and those commuting to the hospital for work, typically opt for private cars. These cars are predominantly privately owned and usually have only one passenger, typically the driver. In contrast, among students, the use of public transportation is more prevalent, although the private car, often utilized through carpooling arrangements, remains a primary alternative mode of transportation. Notably, women and individuals under the age of 26 are the most frequent users of public transport. These findings align with existing literature that underscores the influence of age on mobility choices, with students displaying a greater inclination toward using public transport and walking in comparison to adults [

20,

21,

22,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Gender-related differences in LPT usage vary across studies, with some indicating a higher prevalence of LPT use among women [

9], while others find no significant gender-based differences [

4,

59].

The majority of participants use public transport infrequently. Specifically, less than one-fifth of the respondents consistently utilize the bus to reach the hospital. For those who use the bus sporadically, the car remains the predominant alternative mode of transportation in the vast majority of cases. Consequently, the utilization of public transport services reflects the prevailing trend in contemporary mobility choices, characterized by a dynamic and multifaceted pattern, particularly emphasizing multimodal options where individuals or groups alternate between car usage and bus services. Existing literature highlights the greater adaptability of students in selecting transportation methods [

23,

24,

53]. This flexibility likely stems not only from their lifestyle but also their varying needs and available resources, often necessitating the integration of different modes of transportation for those who do not own a car. The results of this study reveal that students are not the sole category of users who switch between public transport and other transportation means. In fact, the current user base of the public bus service to the hospital extends beyond students, encompassing workers and patients as well, thus presenting new potential scenarios for users.

When examining the travel experience and taking into account both satisfaction with various aspects of the LPT service and the quality of the travel experience assessed through the Satisfaction with Travel Scale, the results indicate that LPT users generally express satisfaction with various aspects of the service. However, they have reservations about the cost and the frequency of service. The frequency of service is particularly crucial for meeting the needs of individuals traveling to the hospital, yet it appears to be the least satisfying aspect in their view. This finding aligns with existing literature [

26,

44], which emphasizes the close relationship between the frequency of service and the perceived quality of the travel experience, alongside factors like comfort, accessibility, and reliability.

It’s worth noting that this research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it revealed some interesting insights. The study found that the ability to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission was associated with a more positive perception of the travel experience. Although using public transport inherently carries a higher risk of contagion compared to using a personal vehicle with no passengers, users of the bus service to the hospital reported satisfaction with this safety aspect. Furthermore, this satisfaction level did not differ significantly from that of non-users of LPT. This could be attributed to the relatively small number of passengers on the bus, allowing for effective social distancing measures to be implemented. It would be valuable to explore in future research whether perceptions of contagion risk for other types of viruses continue to influence the choice of transportation mode or the overall travel experience quality, especially as the pandemic situation evolves.

Furthermore, the results revealed that individuals who exclusively use cars to travel to the hospital express higher satisfaction with their mode of transportation compared to LPT users’ satisfaction with bus services. This outcome aligns with expectations based on existing literature [

9,

10,

60,

61], where cars are praised for their comfort, speed, and, most importantly, the freedom they offer in terms of scheduling and timetables. Interestingly, despite the higher costs associated with using a car compared to public transport, car users report greater satisfaction with the costs incurred than bus passengers. This suggests that the perception of travel cost is not solely based on the actual price but also on the subjective assessment of whether the cost aligns with the benefits provided by the service. It’s worth noting that habitual car users tend to underestimate the true costs of using a car [

62]. Additionally, the cost of using LPT, which users rate as unsatisfactory, appears to be the least influential factor on the overall quality of the travel experience with the specific bus line under consideration in this study.

Taking a closer look at the perception of the travel experience with LPT, the findings indicate that passengers experience predominantly positive emotions characterized by low arousal during bus travel. Passengers primarily feel calm, relaxed, and at ease during their journey, and they perceive the travel experience as generally trouble-free. This emotional component plays a significant role in assessing satisfaction with the service, contributing to passengers’ overall sense of well-being during their trip [

31].

However, it’s important to note that not all passengers shared the same positive judgment of the travel experience, and differences in satisfaction with various aspects of the service emerged, primarily based on age and secondarily on the different categories of users traveling to and from the hospital.

Regarding age, younger passengers reported a less positive travel experience and expressed lower satisfaction with the comfort and hourly coverage of LPT. This finding, consistent with existing literature [

63], might seem contradictory to the higher usage of bus services by young people compared to other age groups. However, this could be explained by the fact that young people often use public transport due to a lack of alternative means, especially private cars, rather than a genuine preference for LPT. This insight helps to understand the negative emotions experienced by younger passengers during their journeys.

Furthermore, the varying needs driving people to travel to the hospital (work, study, or health-related issues) were linked to different levels of satisfaction with certain aspects of the service. Specifically, hospital users (patients, caregivers, and visitors) expressed lower satisfaction than workers and students regarding the time spent on travel and the hourly coverage. This highlights the importance of tailoring measures to promote LPT use based on an analysis of the travel needs of different user groups. By addressing factors that align with the specific needs of various categories of passengers, it becomes possible to enhance overall satisfaction with the service effectively.

This assertion is further reinforced by the differences observed regarding the reasons for not using public transportation (TPL) among various categories of individuals traveling to the hospital. For non-users, such as students, workers, and hospital customers, the primary reasons for not using public transportation were related to inadequate accessibility, insufficient hourly service coverage, longer travel times, and the availability of free parking. In contrast, patients, caregivers, and visitors cited additional reasons for not using TPL, including low punctuality, unreliability, safety concerns, discomfort, and a desire to avoid potential contagion from COVID-19.

These motivations differed from the opinions of regular TPL users, who expressed satisfaction with the service’s reliability, punctuality, and other mentioned aspects. The variation in perceptions of the service between hospital users and students/workers may be linked to negative stereotypes associated with public transportation, where it is often seen as uncomfortable, unreliable, less safe, and lacking punctuality. These stereotypes might result from a lack of knowledge about the actual features of the service. In contrast, workers and students who travel to the hospital more frequently may have a better understanding of the service through their own experiences or the experiences shared by their peers who use it regularly.

To encourage the use of TPL among potential hospital customers, interventions should not only focus on improving service quality but also aim to change the negative and stereotyped perceptions of public transportation. Additionally, the data emphasizes the importance of having accurate information about the service when making travel choices, especially for those without direct or vicarious experience with public transportation.

As previously identified in other studies [

64], individuals who use cars tend to be aware of sustainability issues. In our study, this was particularly true for women, who expressed greater dissatisfaction with the environmental sustainability of car travel compared to men. In contrast, LPT users displayed higher levels of satisfaction with the sustainability of this mode of transportation than those who solely relied on their own cars to reach the hospital. Satisfaction with the sustainability of LPT was found to be positively associated with the perceived quality of the travel experience, albeit to a lesser extent than factors such as comfort, hourly coverage, accessibility, and reliability of the service. Interestingly, these latter factors also played a significant role in the decision not to use LPT. This suggests that while environmental concerns and personal values related to sustainability are important, they may not be sufficient on their own to promote the use of LPT. Instead, individuals also need a service that caters to their specific needs, offering greater accessibility and frequency of trips to accommodate various hospital-related schedules. This appears especially crucial for individuals who have firmly established the habit of using cars and find it challenging to integrate sustainability considerations with the perceived benefits of car travel [

5,

54,

62,

65].

As a case study, the results from our research are not intended for broad generalization. However, they can be valuable for understanding the factors influencing the use or non-use of LPT in similar contexts. These contexts typically involve public transportation serving locations with a high number of users, situated in extra-urban areas characterized by small to medium-sized settlements spaced apart from each other and isolated from rural or industrial areas. Furthermore, the insights gained from understanding the reasons for using or not using LPT can inform specific interventions aimed at promoting its utilization. Our study’s findings can also be useful for comparative purposes, contrasting LPT use in extra-urban areas with that in urban areas or large cities.

Nonetheless, the study does have its limitations, primarily associated with its case study nature. These limitations include a smaller sample of users compared to non-users and an incomplete balance in the sizes of different subgroups of individuals traveling to and from the hospital (students, workers, and hospital customers). Despite these limitations, our results remain relevant as they underscore the importance of recognizing the distinct perceptions and needs of various categories of users and potential users of public transportation services. To effectively promote LPT use in contexts like the one examined in this study, interventions should focus on meeting the diverse mobility requirements of different user groups. Additionally, communication campaigns should address the existing perceptions among users about how LPT can meet their specific needs.

5. Conclusions

Despite car users generally rating their mode of transportation as more comfortable, the study revealed a noteworthy level of satisfaction among users of the examined public bus service. Specifically, users expressed satisfaction with the punctuality, reliability, and safety of the service. These positive aspects stand in contrast to the common Italian stereotype of public transport as unreliable and prone to delays. Furthermore, the data collected indicated a positive assessment of the service’s comfort and its perceived effectiveness in containing the risk of Covid-19 transmission. Again, this contradicts the traditional image of public transport in Italy, often associated with discomfort and overcrowding. These strengths contribute to the overall satisfaction of bus service users.

However, the study also identified certain shortcomings of the LPT. Users expressed dissatisfaction with the service’s scheduling, accessibility (ease of reaching bus stops), and fare cost. As previously discussed in the literature, these critical issues are a source of discontent among LPT users and are among the primary reasons for non-use of the service.

The study also delved into the relationship between the perceived sustainability of LPT, satisfaction with the service, and the motivations behind using LPT. This is an aspect that has not been extensively explored in the literature. The results indicate that LPT passengers tend to be significantly more satisfied with the sustainability of their mode of transport compared to car users. However, sustainability is less closely linked to the quality of the travel experience compared to other factors such as scheduling, frequency of rides, reliability, compliance with scheduled travel times, and comfort. Consequently, sustainability alone may not be sufficient to sway individuals to choose public transport, especially when other conditions, such as scheduling and service accessibility, do not adequately meet their mobility needs. This is particularly true when individuals have the option to use their own cars and there is the availability of free parking at the destination (the availability of free parking at the hospital, in this case, emerged as a significant reason for not using LPT). These findings offer valuable insights for stakeholders seeking to promote LPT use in extra-urban contexts.

Another valuable contribution of this research to the literature is its examination of the differing perceptions of the service among various categories of users and non-users. These categories were not only based on age, gender, or socioeconomic status but also on different travel motivations. The study highlighted that people travel to the hospital for various reasons, including study, work, and medical treatment, leading to different perceptions of the service and varying levels of satisfaction among LPT users. This underscores the importance of understanding the specific needs of different user groups and tailoring policies and interventions to address the diverse needs of these user segments.

Lastly, the data provide valuable insights for policymakers regarding the importance of providing accurate, realistic, and detailed information about the service’s characteristics. This is particularly crucial for potential users who have neither direct nor vicarious experience with the service. A targeted communication campaign aimed at these potential users could help overcome the stereotype of LPT as unreliable and the resulting resistance to its use.