1. Introduction

The impact of dietary habits, such as meal frequency, meal timing, and skipping meals, have been studied extensively in the last decade because of their association with the development of non-communicable diseases [

1,

2]. As of 2019, non-communicable diseases have been responsible for 74% of deaths worldwide [

3]. The role of macro and micronutrients is essential in understanding the rise in the rates of non-communicable diseases; nonetheless, epidemiological studies have demonstrated the significance of dietary habits on health [

1,

4].

The number and the timing of daily meals have been associated with diabetes [

5], obesity [

6], and metabolic syndrome [

7]. Skipping meals has been associated with obesity [

8], low intake of recommended nutrients [

9], and an increase in odds of metabolic syndrome [

10]. Moreover, night-time eating has been associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome [

11] and an increased rate of obesity [

12]. Dietary habits such as meal timing, frequency, skipping meals, and fasting impact metabolic outcomes [

2].

Skipping breakfast and eating late-night dinners are associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease [

12,

13]. This was demonstrated in a cross-over study in which individuals were given a diet with the same macronutrient composition but at different times on different dates, a dinner at 6 p.m. and a late dinner at 10 p.m [

14]. The study showed that eating late dinner is associated with glucose intolerance and reduces fatty acid oxidation and mobilization, especially in early sleepers. Another prospective cohort study assessed the association between meal frequency and type 2 diabetes among community-dwelling adults aged 45 years and older [

5]. The study demonstrated that eating four meals a day, compared to eating three meals a day, was associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, especially among normal-weight individuals (BMI<25 kg/m

2).

Most published studies on meal timing and frequency were conducted in the United States, Europe, or Asia. As there is a need for more research in this area in the Middle East, the data from Kuwait National Nutrition Surveillance System provided an opportunity to describe meal timing and frequency in Kuwait. Seventy-two percent of deaths in Kuwait have been attributed to non-communicable diseases [

15], and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is about 36% [

16]. Studies demonstrate that non-communicable diseases and metabolic syndrome are associated with dietary habits. Thus, it is essential to examine how dietary habits affect the Kuwaiti population to better understand the country's high prevalence of chronic diseases. This paper aimed to describe dietary habits, including meal timing, meal frequency, skipping meals, and late-night eating in Kuwaiti adults.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Sample

The study population comprises a nationally representative sample of the Kuwait National Nutrition Surveillance System (KNNSS). The study followed a stratified cluster sampling strategy obtained from 545 individual households from Kuwait's six governorates. To sample the households, the governorates were divided into 82 clusters, and 20 households were selected from each cluster. From each household, subjects over 20 years of age were randomly selected. Of the 1824 individuals that participated in the KNNSS, 757 adults were included in this study. In total, 722 individuals were not included because they were less than 20 years of age. Those younger than 20 years were assessed in KNNSS differently as adolescents and children. Another 345 individuals were excluded because they were taking diabetes, blood pressure, or cholesterol medication.

Assessment of Dietary Data

The participants completed a 24-hour dietary recall. Meal frequency was estimated based on the number of eating episodes. An eating episode was consuming any food or beverage of more than 1 Kcal. Skipping breakfast was defined as not eating a meal from 5 a.m. to 10 a.m. Skipping dinner was defined as not eating a meal from 6 p.m. to 10 a.m. Late-night eating was defined as eating a meal between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m. Fasting was calculated by subtracting the time of the last meal from the time of the first meal.

Covariate Assessment

Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to collect data on demographic background, physical status, and lifestyle factors. Body measurements, such as body weight, height, and waist circumference were obtained during the household visit through standard protocol by trained personnel. All biomarkers were measured by collecting blood samples during the house visits after an overnight fast. Two measurements were taken for blood pressure, waist circumference, body weight, and height. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Age was defined into two categories for adults: 20-49 years and 50 years and older. Smoking was defined as ever smoking a cigarette (Yes/No). Physical activity was defined as being physically active or having a sedentary lifestyle (Active/ Sedentary). Marriage was defined as those who are married and those who are not married, including divorced and widowed (Yes/No). Education was classified into six categories (less than middle school, middle school, high school, diploma, Bachelor’s, and postgraduate).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software. Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard error of the mean and all categorical variables were presented as frequency (n) and/or percentiles (%). For meal frequency, individuals were divided into those who consume three meals or less, four meals, five meals, and six meals or more. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted between the four groups of meal frequency to determine if there was at least one different group in the mean or frequency. A t-test was conducted to identify if there was a difference in dietary habits between the two groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of participants in the study (n=757). The study included only adults over 20 years, of which 623 (82.3%) were 20 to 49 years and 134 (17.7%) were 50 years and older. There were 341 (45.05%) males and 416 (54.95%) females. The majority of the participants, 217 (28.67%), had a bachelor’s degree. Late-night eating was the most popular eating habit among participants in the study (53.9%), followed by skipping breakfast (29%) and skipping dinner (9.8%). The average duration of night fasting was 9.8 ± 3.3 hours. The average BMI for males and females was 28.3+5.9 kg/m

2 and 29.9 + 6.7 kg/m2, respectively. The mean waist circumference was 93.34 ± 16.3 cm. An estimated 33% (251) of the adults were smokers, while 41% (310) followed an active lifestyle. The mean blood pressure was 124.9/80.47 mmHg in this study. The mean HbA1c was 5.7± 0.88, while the mean triglycerides were 1.3 ± 0.74 mmol/L.

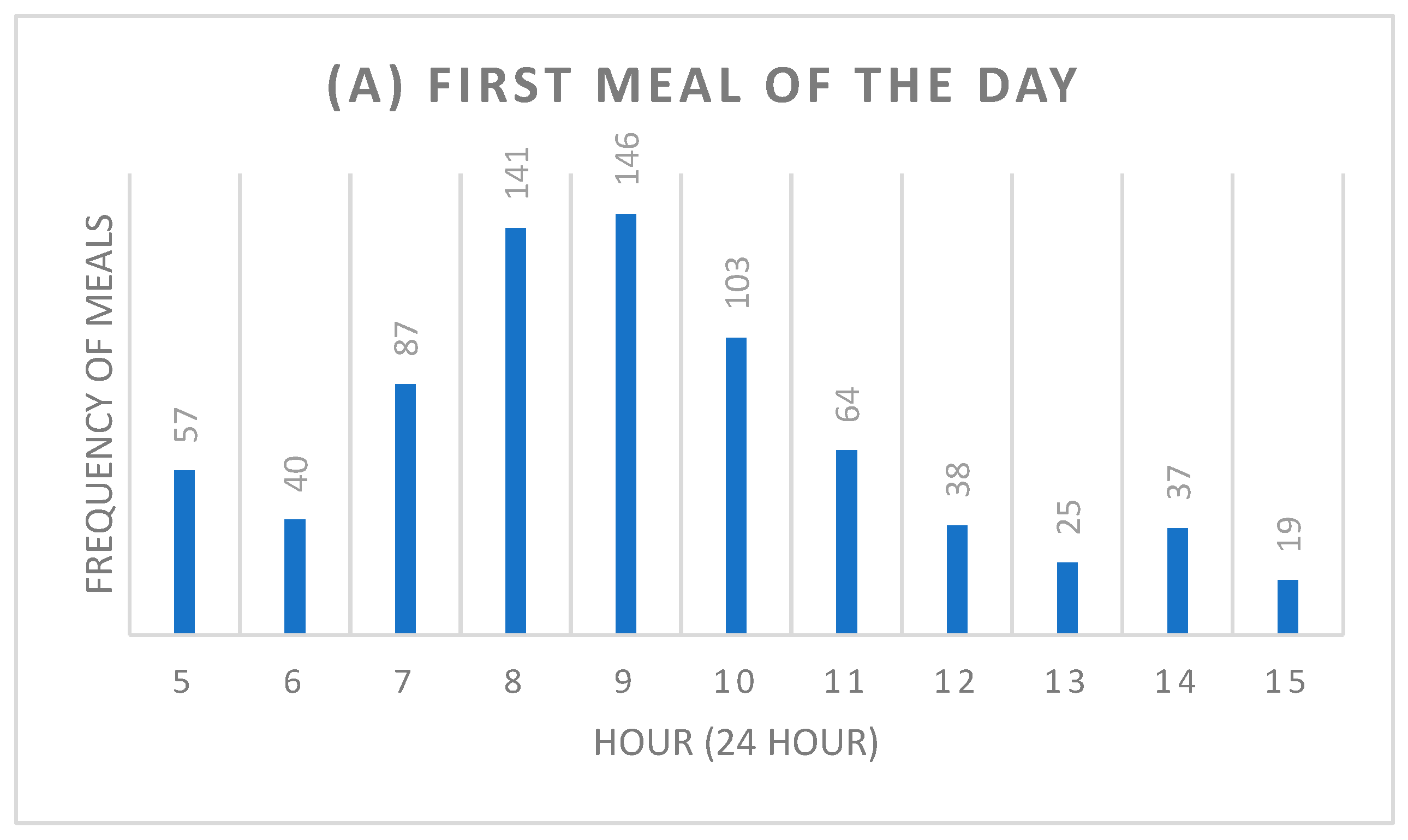

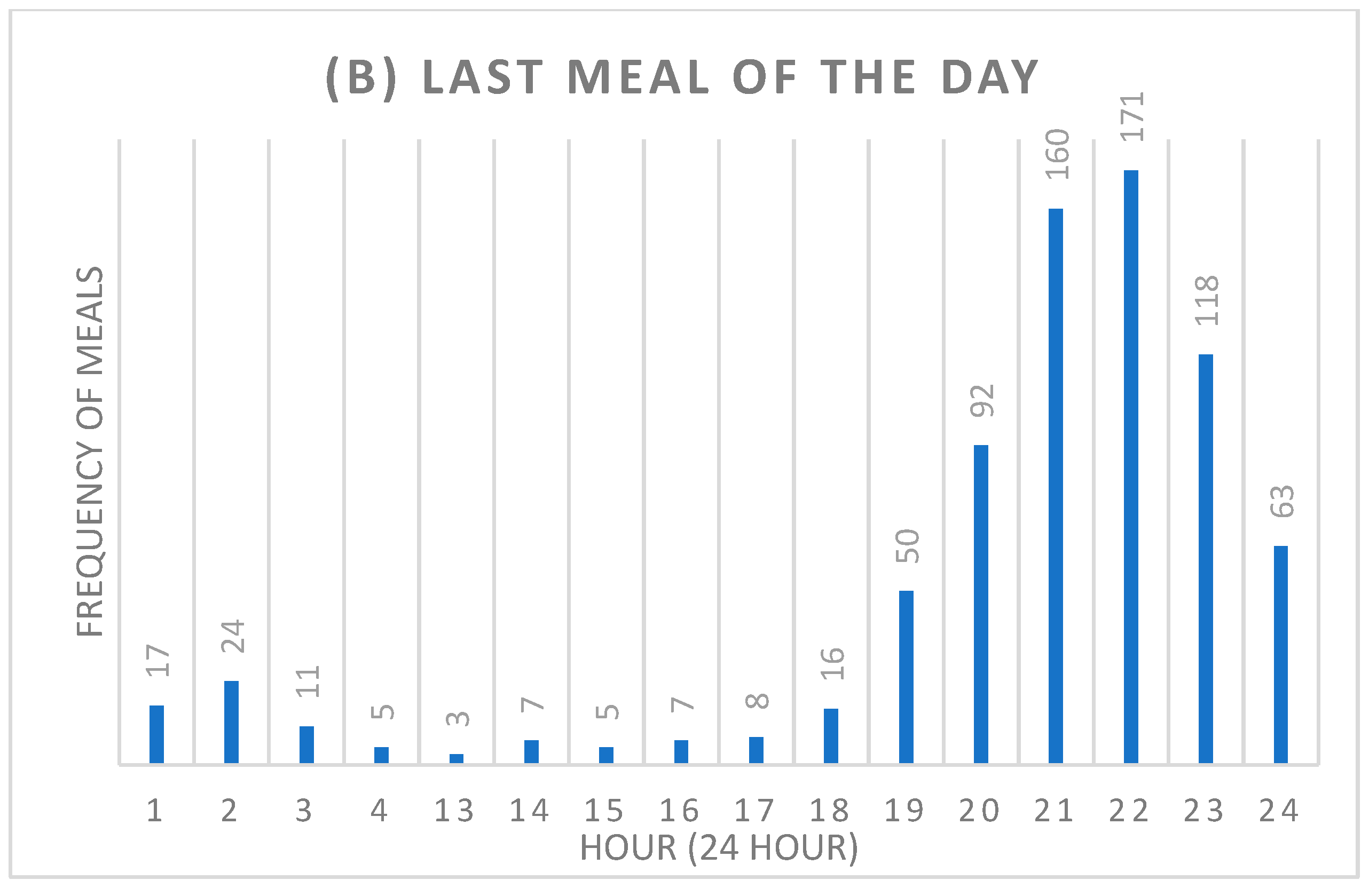

The mean number of meals consumed per day was 4.4 meals (

Table 2). The majority of the participants consumed four meals (29.9 %) daily, followed by five meals (27.3%), three meals (20%), six meals (12.3%), and two meals (5%). Furthermore, most of the participants (19.3%) consumed their first meal of the day at either 9 a.m. (19.3%) or 8 a.m. (18.6%) (

Figure 1). On the other hand, 22.6% of the participants consumed their last meal of the day at 10 p.m., followed by 21.1% at 9 p.m. (

Figure 1).

The general characteristics of the men and women in the study according to their meal frequency are shown in

Table 3. Compared with individuals who ate three or fewer meals per day, individuals who ate six meals or more per day were more likely to be men, married, consume meals after 10 p.m., have higher serum triglyceride, and fast for a shorter duration (

p<0.05). Furthermore, individuals who ate six or more meals per day were less likely to skip breakfast and dinner compared to individuals who ate three or fewer meals per day (

p<0.0001). Marital status, smoking, activity level, BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, HbA1, total serum cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol did not significantly differ based on meal frequency among the participants.

An estimated 35.3% of the females and 23.5% of the males skipped breakfast (

Table 4), which was significantly different (

p= 0.0004). There was no difference in the proportion of males and females who skipped dinner. There was a significant difference (

p= 0.0373) between the genders in which 58.1 % of the males and 50.5% of the females ate late at night. Duration of fasting was significantly (

p<0.0001) different between the genders; men fast at night on average for a period of 10.1 ± 2.8 hours, and women fast on average for 10.9 ± 2.9 hours.

Dietary habits differed based on the participants' marital status (

Table 4). A significant difference was found in the proportion of participants who skipped breakfast, as more unmarried participants skipped breakfast (36.5%) than married participants (27.6%). Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of the unmarried participants (13.8%) skipped dinner than the married participants (8.3%). Furthermore, the unmarried participants were fasting during the night than married participants, and the fasting durations were 10.9 and 10.4 hours, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that 757 participants aged 20 and older consumed 4.4 meals daily. Most of the study participants consumed four meals (29.9%) or five meals (27.5%) daily. Moreover, 29% of the participants skipped breakfast, 53.9% ate meals later than 10 p.m., and only 9.8% skipped dinner. Dietary habits, including meal frequency, meal timing, skipping meals, and fasting, have been shown to be as vital as nutrients in influencing health outcomes [

1]. Thus, understanding and tracking the dietary habits of a community is essential to overcome chronic health conditions [

2].

The results of this study are unique to adults in Kuwait, yet it is important to see how they compare to other studies. The average number of meals consumed daily by the study participants (4.4 meals) is lower than the average of 5.7 meals and snacks consumed daily by US adults based on the NHANES survey (1971-2010) [

17]. Although the NHANES survey calculated meals and snacks separately, this study assessed all eating events as meals, whether a snack or a heavy meal. Higher meal consumption is linked to a healthier lifestyle and better health outcomes [

18]. Nonetheless, factors other than meal frequency, such as meal timing, play into the benefit of the meal to the individual.

Skipping breakfast is associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity [

19]. In this study, 29% of the participants skipped breakfast or did not eat a meal until 11 a.m. The results are similar to a recent study on breakfast consumption in Kuwait among adolescents which illustrated that 21.7% of the adolescents never consumed breakfast or consumed it only once per week [

20]. However, the habit of skipping breakfast differs in each country as a study of Korean adults revealed that 41.2% skipped breakfast [

21]. Another cohort study in Japan revealed that 38.8% of the participants skipped dinner [

22]. In contrast, a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia revealed that 42% of medical students skipped breakfast [

23]. A study of US adults shows that only 5.1% never consumed breakfast, while 10.9% rarely consumed breakfast [

24].

Dinner is as essential as breakfast in determining health outcomes. Eating a late dinner or bedtime snack and skipping dinner have been associated with an increased risk of obesity and overweight [

25,

26]. In this study, 9.8% skipped dinner and 53.9% had a meal later than 10 p.m. The number of participants who ate late at night is comparable with other studies. A cohort study in Japan demonstrated that 57.1% had a late night dinner [

22], while 49.7% of medical students in Saudi Arabia reported having a late night dinner [

23]. The proportion of the population who skipped dinner (9.8%) was low compared to those who skipped breakfast (29%). However, it is relatively high compared to a cohort study in Japan, where 2.4% of university students skipped or ate dinner occasionally [

26].

The frequency and timing of meals are associated with increased blood glucose levels and triglycerides [

5,

27]. This study demonstrated significant differences in serum triglycerides between individuals who ate different amount of meals. As the frequency of meals increases, serum triglycerides increase. This finding was similar to an Australian study evaluating the association of meal frequency with the risk of metabolic syndrome that illustrated that higher meal frequency was associated with elevated triglyceride levels among men [

28].

There are some potential limitations to this study. First, the study extracted meal timing and frequency from the 24-hour dietary recall. There were no specific questions on skipping meals and the number of snacks or meals consumed daily in the questionnaire administered during the study. Instead, the data collected in 2010 in Kuwait's National Nutrition Surveillance System was utilized as secondary data to calculate meal timing and frequency. Second, since this was collected from a 24-hour food recall, all eating events were treated as meals without differentiating between snacks and meals. Thus, comparing this study to studies that reported meals and snacks is challenging.

5. Conclusions

Adults in Kuwait who are 20 years and older demonstrate dietary habits unique to Kuwait's culture. Around 54% of the study participants eat a meal after 10 p.m., while only 29% skip breakfast and 9.8% skip dinner. The high proportions of late-night eaters and breakfast skippers could be attributed to cultural practices in Kuwait. However, it is crucial to investigate the implications of those dietary habits on health in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.; methodology, F.A.; formal analysis, F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A. and C.D.; visualization, F.A. and C.D.; supervision, C.D.; project administration, .S.AH., S.AZ. and H.O; funding acquisition, S.AH., S.AZ. and H.O.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Science, grant number 2003-1202-02.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation 2016, 133, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhulaifi, F.; Darkoh, C. Meal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Disease. 2022; https: //www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.; Janssen, I.; Dawson, J.; et al. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity research 2004, 12, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Qin, L.-Q.; Dong, J.-Y. Meal frequency and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study. British Journal of Nutrition 2022, 128, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmbäck, I.; Ericson, U.; Gullberg, B.; Wirfält, E. A high eating frequency is associated with an overall healthy lifestyle in middle-aged men and women and reduced likelihood of general and central obesity in men. British journal of nutrition 2010, 104, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titan, S.M.; Bingham, S.; Welch, A.; et al. Frequency of eating and concentrations of serum cholesterol in the Norfolk population of the European prospective investigation into cancer (EPIC-Norfolk): cross sectional study. Bmj 2001, 323, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnko, S.; Du Pré, B.C.; Sluijter, J.P.; Van Laake, L.W. Circadian rhythms and the molecular clock in cardiovascular biology and disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2019, 16, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastorini, C.-M.; Milionis, H.J.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Panagiotakos, D.B. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. Journal of the American college of cardiology 2011, 57, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, Y.; Bromage, S.; et al. Application of the Global Diet Quality Score in Chinese adults to evaluate the double burden of nutrient inadequacy and metabolic syndrome. The Journal of nutrition 2021, 151 suppl. 2, 93S–100S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Circadian Rhythm. 2021; https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/fact-sheets/Pages/circadian-rhythms.aspx. Accessed 5/2021.

- Jakubowicz, D.; Barnea, M.; Wainstein, J.; Froy, O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity 2013, 21, 2504–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Gall, S.L.; McNaughton, S.A.; Blizzard, L.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Skipping breakfast: longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 92, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Brereton, N.; Schweitzer, A.; et al. Metabolic effects of late dinner in healthy volunteers—a randomized crossover clinical trial. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020, 105, 2789–2802. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Kuwait Noncommmunicable Diseases Profile. 2016.

- Al Zenki, S.; Al Omirah, H.; Al Hooti, S.; et al. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Kuwaiti adults—a wake-up call for public health intervention. International journal of environmental research and public health 2012, 9, 1984–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, A.; Graubard, B. 40-year trends in meal and snack eating behaviors of American adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2015, 115, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.; Coates, A.M.; Banks, S. Meal timing, sleep, and cardiometabolic outcomes. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research. 2021, 18, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Q.; Pu, Y.; et al. Skipping breakfast is associated with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity research & clinical practice 2020, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aldwairji, M.; Husain, W.; Al Qaoud, N.; Al Shami, E. Breakfast consumption habits and prevalence of overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. J Nutr Health Food Eng 2018, 8, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Jeong, H.; Kim, M. A survey on the breakfast skipping rate of Korean adults relative to their lifestyle and breakfast skipping reasons and dietary behavior of breakfast skippers. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition 2010, 15, 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kito, K.; Kuriyama, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Nakayama, T. Impacts of skipping breakfast and late dinner on the incidence of being overweight: a 3-year retrospective cohort study of men aged 20–49 years. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2019, 32, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghani, H.O.; Albalawi, K.S.; Alali, O.Y.; et al. Breakfast skipping, late dinner intake and chronotype (eveningness-morningness) among medical students in Tabuk City, Saudi Arabia. The Pan African Medical Journal 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, S.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Xu, G.; et al. Association of skipping breakfast with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2019, 73, 2025–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, C.; Imano, H.; Muraki, I.; Yamada, K.; Iso, H. The association of having a late dinner or bedtime snack and skipping breakfast with overweight in Japanese women. Journal of obesity 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, R.; Tomi, R.; Shinzawa, M.; et al. Associations of skipping breakfast, lunch, and dinner with weight gain and overweight/obesity in university students: a retrospective cohort study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Medina-Inojosa, J.; et al. Association between eating time interval and frequency with ideal cardiovascular health: Results from a random sample Czech urban population. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2018, 28, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Blizzard, L.; McNaughton, S.A.; Gall, S.L.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Daily eating frequency and cardiometabolic risk factors in young Australian adults: cross-sectional analyses. British journal of nutrition 2012, 108, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).