1. Introduction

Social trust reflects a belief in mutual commitment, a person's expectation of others to be fair, trustworthy, cooperative, and act according to accepted societal norms. Social trust is based on the assumption that in general, we can rely on others (Rotter, 1967). Here, "others" encompasses diverse groups and societal institutions, ranging from governmental bodies and legal entities to leaders and organizations. Trust and trustworthiness are essential for creating and maintaining positive and effective relationships between people in society (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002; Glaeser et al., 2000).

In numerous social and economic interactions, both individuals and enterprises often grapple with an absence of critical information needed for informed decision-making. Frequently, these interactions necessitate establishing trust with unfamiliar entities. We place our faith in service and product providers, anticipating they deliver quality and value. We rely on companies offering guarantees, believing they will remain operational when their commitment is called upon. Similarly, we entrust banks with our financial assets, expecting them to safeguard our savings and retirement funds for future use. Moreover, we confide in medical professionals, hoping they provide optimal care, even when we lack the expertise to evaluate the medical interventions they administer. In some cases, contracts cannot be enforced or regulated through sanctions, guarantees, or other enforcement mechanisms that will guarantee their implementation according to the expectations of the parties. Therefore, in many cases, a lack of trust and credibility will cause the failure of the transaction, which will adversely affect individuals and the economy and impair the scope and effectiveness of economic activity (Zak and Knack, 2001).

Placing trust in individuals or entities that prove to be unreliable can lead to adverse outcomes. Entrusting such unreliable parties poses risks, potentially resulting in disappointment and detriment. Previous studies have indicated that elderly individuals, due to various factors, are more inclined to trust unfamiliar individuals compared to their younger counterparts. This predisposition renders them more susceptible to the tactics of marketers and deceitful individuals (Hough, 2004; Bayer, 2019; Bayer et al., 2018)

Analyzing the differential trust dynamics across distinct age cohorts is fundamental to a comprehensive understanding of decision-making processes and their inherent variations throughout sequential life stages. Moreover, a meticulous examination of the trust tendencies inherent within the geriatric demographic is imperative, especially given their heightened susceptibility to economic transgressions. Such an exploration can not only aid in preempting these deceptive undertakings but also shed light on the contributory factors that engender them.1.

The incorporation of standardized questions pertaining to general and social trust within expansive socio-economic surveys facilitates profound interdisciplinary investigations into the realm of social trust. This manuscript delves into the relationship between generalized trust and age, drawing data from the World Values Survey (WVS) questionnaire distributed in 2011 within the United States. Our decision to utilize U.S. data stems from prior research indicating a propensity for senior citizens in the U.S. to be prime targets for financial malfeasance, largely attributed to the perception that they exhibit greater trust towards marketers compared to their younger counterparts (Bayer, 2019; Hough, 2004). Notwithstanding the significance of this topic, especially in an era characterized by demographic aging, there exists a paucity of research exploring the nexus between age and generalized trust within the broader populace, with an even more limited focus on Western nations. This study seeks to interrogate the postulation that generalized trust varies across age demographics, while concurrently accounting for an array of control variables, including gender, income, educational attainment, ethnic background, and religious affiliation.

2. Literature review

The intricate web of interactions among societal members is conceptualized as social capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). This form of capital is a pivotal asset for any community, with social trust serving as a foundational component (Putnam, 2000).

Existing scholarly literature differentiates between personalized and generalized trust. The former pertains to trust vested in acquaintances or individuals known personally, while the latter encompasses trust extended to unfamiliar individuals (Stolle,1998). Generalized trust gauges an individual's conviction that most people can be deemed trustworthy (Cook, 2016; Nieminen et al., 2008) and serves as an indicator of a citizenry's predisposition towards collaboration (Putnam, 2000).

The magnitude of trust individuals harbor for one another is shaped by an amalgamation of personal experiences and the inherent attributes of their societal and communal milieu. Trust is perceived as a scenario wherein the trustor willingly exposes themselves to potential vulnerability, predicated on the hopeful anticipation of the trustee's actions and intentions (Rousseau et al., 1998).

At an individualistic dimension, trust is sculpted by intrinsic values, cultural paradigms, and overarching worldviews, further nuanced by factors such as financial status, occupational standing, and educational attainment (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2002; Bayer, 2022). Knack and Keefer (1997) found a positive correlation between social trust and levels of education. They argue that higher schooling implies that individuals turn out to be better informed, better at interpreting perceived information, and more conscious of the consequences of actions taken by themselves and others. Furthermore, the educational milieu fosters a process of socialization, potentially augmenting propensities to trust. Putnam (2000) contends that trust is cultivated through iterative interpersonal engagements, with educational institutions serving as crucibles for such trust-building interactions.

Previous scholarly endeavors have identified a positive linkage between an individual's socio-economic standing and their propensity for social trust (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Hamamura, 2012). This association can be attributed to the interplay of societal stigmatization and hierarchical positioning. From this framework, individuals situated at lower socio-economic tiers, often subjected to societal marginalization and derision, may adopt a more psychologically defensive approach (Henry, 2009). Such psychological barriers often translate into diminished trust inclinations (Brandt & Henry, 2012; Brandt et al, 2015). Individuals exposed to racial discrimination may be characterized by lower levels of trust. Inequality may affect the level of trust, due to the creation of social perceptions of injustice (Brockner & Siegel, 1996).

Cultural variances have been linked to disparities in generalized trust levels (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013a). The construction of trust is significantly influenced by social networks (Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1985; Putnam, 2000; Van Lange, 2015). Affiliation to specific groups impacts trust dynamics; individuals often anticipate ethical conduct from fellow group members as opposed to those outside their social circle. Such anticipations lead to a heightened inclination to trust within-group members over outsiders (Platow et al., 2012; Tanis & Postmes, 2005). Consequently, individuals residing in a specific locale for extended durations, likely exhibiting deeper social and cultural integration, may manifest elevated trust levels towards others (Alesina et al., 2004).

Variations in social trust are evident not only at an individual level but also on a broader national spectrum, with the societal fabric of nations shaping trust dynamics. An examination of the WVS data underscores this variation, highlighting that while 66.1% of respondents in the Netherlands expressed trust in others, this figure plummeted to 3.2% in nations like Trinidad and Tobago and the Philippines (World Values Survey Association, 2010-2014 wave). Notably, many countries in Eastern Asia often report lower generalized trust levels compared to Western nations (Hu, 2015). Research by Zak and Knack (2001) suggests a negative association between the heterogeneity of a population and its overall trust levels. Leigh (2006) further illuminated this by revealing that countries with pronounced inequality and ethnic diversity tend to have reduced trust levels. This sentiment is echoed in subsequent studies that link ethnic diversity to diminished trust (Cook & Cooper, 2003; Kandori, 1988). Furthermore, religious dynamics, encompassing the dominant religion and religious pluralism within a nation, have been identified as significant determinants of trust variations (Bjørnskov, 2012; Delhey and Newton 2005; Dilmaghani, 2017, La Porta et al., 1996; Zak and Knack, 2001).

The significance of trust in bolstering economic efficiency and the observed variations in trust across diverse cultural landscapes have been a focal point of scholarly inquiry over the past few decades (Brown and Uslaner 2005; Berggren and Jordahl 2006; Delhey and Newton 2005; Nannestad 2008). Trust, coupled with credibility, streamlines economic interactions, eases credit access, and diminishes the imperative for resource allocation toward rights protection and enforcement. Consequently, trust acts as a catalyst in reducing transactional overheads, fostering collaboration, and stimulating economic ventures (Knack and Keefer 1997).

Despite the difficulty in proving causality, empirical research has discerned associations between a nation's social trust levels and pivotal economic performance indicators. Knack and Keefer (1997) used data from different countries and found correlations between higher levels of social trust and higher per capita GDP. High levels of social trust have been found to correlate with economic efficiency and economic growth (Berggren et al., 2008; Bjørnskov, 2012; Knack and Keefer, 1997; Zak and Knack, 2001), higher education registration rates (Bjørnskov 2009; Papagapitos and Riley 2009), government stability (Knack, 1999; Nooteboom, 2007; Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005), more efficient legal systems, more effective government bureaucracy, lower level of corruption (Guiso et al., 2004; La Porta et al., 1996), cooperatively behavior, life expectancy, greater life satisfaction, and greater physical health (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013b; Barefoot et al., 1998; Helliwell et al., 2014; Simpson, 2007; Yamagishi, 2011).

Within organizational contexts, social trust emerges as a pivotal element. Studies investigating the creation and evolution of trust in work teams underscore the profound link between intra-team trust and both collaboration and overall performance (Jones & George, 1998). Similarly, research centered on sports teams discerned a connection between the degree of trust vested in the team's coach and the team's ensuing performance outcomes (Mach et al., 2010).

Numerous empirical studies have explored the interplay between age and social trust. Erikson (1993) contends that the cultivation of trust is pivotal for the development of a holistic personality and successful social integration. He further postulates that this trust propensity becomes increasingly salient for the elderly, given the significance of personal relationships and trust-based social networks in their lives. Research on elderly-targeted fraud suggests that the elderly, in general, exhibit a heightened inclination to trust, even in contexts involving sales representatives (Hough, 2004). Consequently, many senior citizens, predisposed to trust, may approach marketers' propositions with a degree of naiveté, rendering them susceptible to fraudulent schemes (Hough, 2004). In a methodological study employing the "trust game" with a representative sample of German households, Fehr et al. (2003) discerned no statistically significant correlation between in-game behavior, gender, and income. However, age emerged as a significant determinant influencing game dynamics. Notably, participants aged 65 and above demonstrated a more cautious approach (evidenced by their lower stakes in the game) compared to their counterparts in their thirties and forties. Moreover, the propensity for trust reciprocity, as measured by the game's return metrics, was observed to increase with age. A congruent study by Bellemare and Kröger (2006) with Dutch households corroborated these findings. While age-related variations were statistically significant, the magnitude of differences in both trust and reciprocity dimensions remained relatively modest.

Sutter and Kocher (2007) conducted a laboratory experiment to investigate trust levels across various age groups. Their findings indicated that trust exhibited an almost linear increase from early childhood to early adulthood, yet remained relatively stable across different adult age brackets.

Hu (2015) embarked on a study to explore the evolution of generalized trust in mainland China spanning the years 1990 to 2007. Utilizing repeated cross-sectional survey data from the World Values Survey, Hu delineated the age, period, and cohort effects on the generalized trust of Chinese citizens. His analysis revealed a downward trajectory in the level of generalized trust over the period from 1990 to 2007. Furthermore, he observed that an individual's trust in an average societal member tends to augment with age. Notably, Hu (2015) discerned that cohorts exposed to the totalitarian Mao Era during their formative years exhibited markedly lower trust in generalized others compared to cohorts whose formative years coincided with the reform era. This observation underscores the influence of generational experiences on the trust propensity of a given generation.

While prior research has posited that elderly individuals exhibit a greater propensity to trust strangers compared to their younger counterparts, there exists a limited empirical examination of variations in generalized trust across age demographics within the broader population, particularly within the context of the United States and other Western nations2.

Given the diverse conclusions presented in scholarly literature regarding social trust, the influence of cultural variations on trust levels, and the notable research gap pertaining to Western nations, this study seeks to investigate the association between age and generalized trust within the broader populace of the United States, utilizing data from the WVS, while accounting for other pertinent influencing variables.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. The Research population and the WVS questionnaire

We employ multiple probit regression models, utilizing individual data derived from the most recent wave of the World Values Survey (WVS) for the United States, gathered in 2011. The World Values Survey, accessible at

www.worldvaluessurvey.org, represents a consortium comprising a vast cadre of social scientists dedicated to empirical research. The primary objective of WVS is to scrutinize shifts in societal values and discern the consequential impacts on socio-political dynamics. Since its inception in 1981, the WVS has progressively broadened its scope, both in terms of the number of nations surveyed and the depth of the questionnaires. Presently, these questionnaires are disseminated across approximately 100 countries, encompassing an eclectic mix of queries pertaining to beliefs, cultural nuances, demographics, values, and more. Each questionnaire is exhaustive, featuring around 270 questions spanning diverse subjects, and is tailored to resonate with the specificities of individual countries (Inglehart et al., 2014). Notably, the questionnaire dedicates a segment to the exploration of social trust.

The most recent survey conducted in the United States in 2011 encompassed a sample of 2,232 respondents, ranging in age from 18 to 93. The degree of social trust was assessed through a self-administered questionnaire, probing the participant's trust in others. Given the comprehensive nature of the questionnaire topics and the substantial sample size, it facilitates a robust statistical evaluation of overarching social trust, factoring in relevant control variables. The primary variables employed in this research are delineated in the subsequent table:

Table 1.

Description and explanation of the variables in the study. Data for the United States, WVS 2011.

Table 1.

Description and explanation of the variables in the study. Data for the United States, WVS 2011.

| Table 1: Definitions of main variables. |

|

| Variable |

Definition |

| Generalized trust |

The WVS question is framed as: "Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?" The answers are binary with the value of 1 attributed to the respondents opting for the first statement. |

| Age |

The WVS question is framed as ''Age. This means you are ____ years old'' |

| Gender |

The answers are binary with the value of 1 for women and 0 for men. |

| Level of Education |

The highest educational level the respondent attained (8 categories) |

| Income level |

The WVS question is framed as "On this card is an income scale on which 1 indicates the lowest income group and 10 the highest income group in your country. We would like to know in what group your household is. Please, specify the appropriate number, counting all wages, salaries, pensions, and other incomes that come in.” The answers get the value of 9 to 0. 9 for the tenth step, and 0 for the lower step. |

| Language at home |

The WVS question is framed as "What language do you normally speak at home?” The categories are Chinese, English, French, Japanese, Spanish; Castilian, and Other. |

| Language at home: English |

A dummy variable that gets the value 1 for English and 0 for others. |

| Language at home: Spanish |

A dummy variable that gets the value 1 for Spanish and 0 for others. |

| Immigrant |

The WVS question is framed as: "Were you born in this country or are you an immigrant?" The answers are binary with the value of 1 immigrant and 0 for none immigrants. |

| Ethnic Group |

The categories are: "2+Races, Non-Hispanic," "Hispanic,” "Other, Non-Hispanic", "Black, Non-Hispanic," and ''White, Non-Hispanic" |

| Religious denomination |

The WVS question is framed as "Do you belong to a religion or religious denomination? If yes, which one?” The categories are None, Buddhist, Hindu, Jew, Muslim, Orthodox, Other: not specific, Protestant, and Roman Catholic. |

| Protestant |

A dummy variable that gets the value 1 for Protestants and 0 for others. |

| African-American |

A dummy variable that gets the value 1 for African-Americans and 0 for others. |

The following table shows sample characteristics:

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample. Data for the United States, WVS 2011.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample. Data for the United States, WVS 2011.

| Max |

Min |

Std. Dev. |

Mean |

|

|

Obs |

Variable |

| 93 |

18 |

16.91 |

48.91 |

|

|

2232 |

Age |

| 8 |

0 |

1.61 |

1.76 |

|

|

2215 |

Number of children |

| 9 |

0 |

1.91 |

4.16 |

|

|

2168 |

Income (10 steps) |

| 3 |

0 |

1.05 |

1.85 |

|

|

2232 |

Level of Education (Incomplete secondary school and down=0) |

| |

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

|

Dummy Variables |

| 1 |

0 |

0.5 |

0.51 |

1084 |

1148 |

2232 |

Gender (Female=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.28 |

0.08 |

183 |

2016 |

2199 |

People whose native language is not English (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.25 |

0.66 |

2054 |

145 |

2199 |

Language at home: Spanish (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.45 |

0.28 |

1613 |

619 |

2232 |

Non-Caucasian (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.45 |

0.28 |

1577 |

610 |

2187 |

Protestant (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

2016 |

216 |

2232 |

African-American (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.38 |

0.18 |

1839 |

393 |

2232 |

Single (Yes=1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.46 |

0.7 |

660 |

1555 |

2215 |

Do you have children (Yes = 1) |

| 1 |

0 |

0.32 |

0.11 |

1953 |

247 |

2200 |

Respondent immigrant (Yes=1) |

3.2. Generalized trust: Descriptive statistics

In the WVS version of the generalized trust question, the respondents were asked whether most people could be trusted and had to choose between two approaches, the first: "Most people can be trusted" and the second: "Need to be very careful."

The subsequent table delineates the collective response to the generalized trust inquiry within the questionnaire:

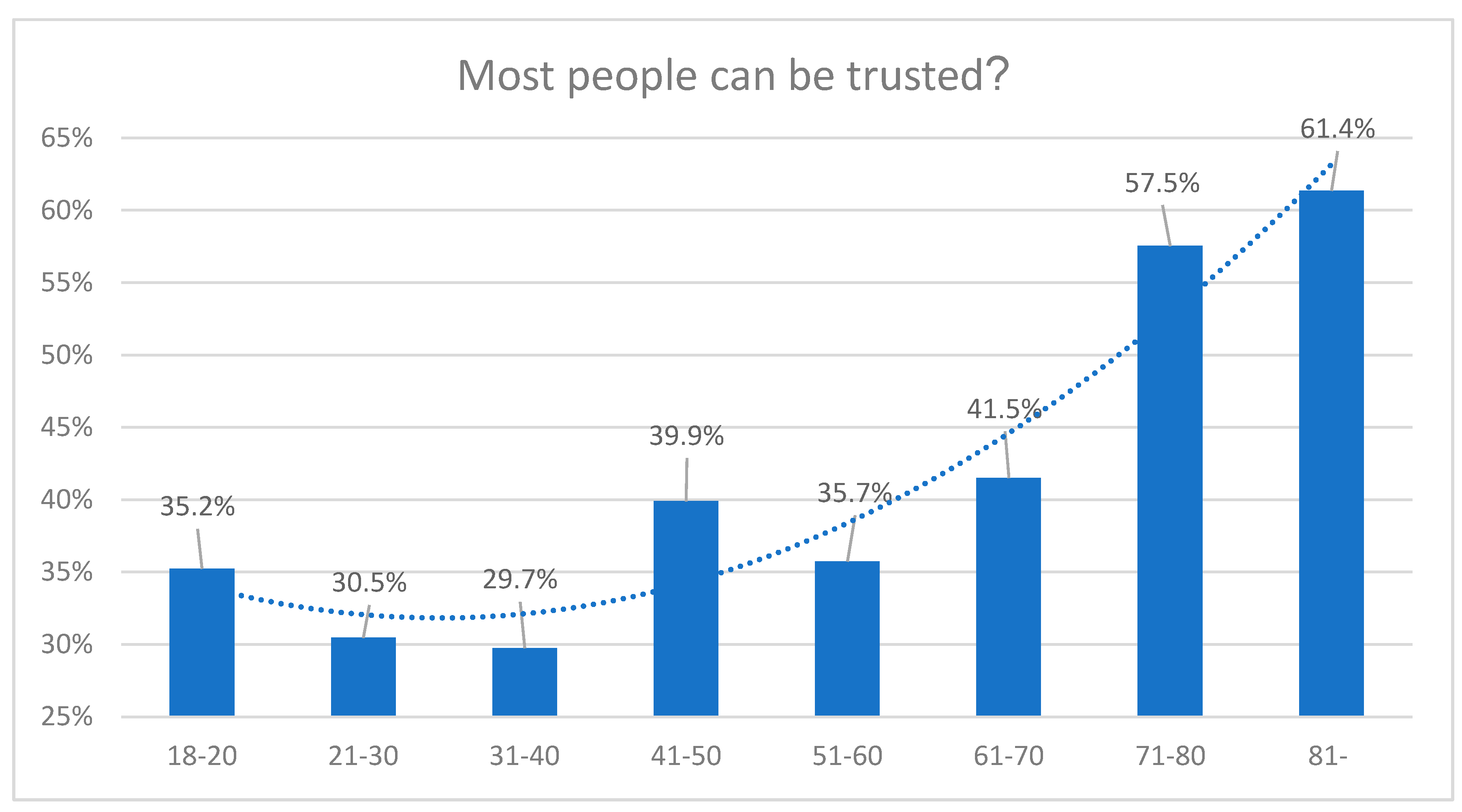

As depicted in

Table 3, over 61% of the respondents advocate for prudence, expressing skepticism towards the trustworthiness of most individuals. To discern if there exists a correlation between the respondents' age and their inclination to trust, the responses were categorized by age brackets. The ensuing figure illustrates the responses to the generalized trust query, segmented by age group. The graph represents those who conveyed trust in most people, of the total respondents who addressed the question, excluding 21 respondents who did not answer this question (N = 2211).

As depicted in

Figure 1, there's a noticeable inclination among those aged 20-40 to harbor mistrust towards others. Generally, only about 30-40% of participants up to the age of 60 believe that the most people are trustworthy. This percentage experiences variations within this age range, peaking notably at roughly 39.9% for those between 41-50 years. However, beyond the age of 60, there's a clear shift with individuals displaying heightened trust. This trend is slightly more evident among those aged 61-70 and becomes considerably pronounced for individuals aged 70 and beyond, where the trust level rises to approximately 60%.

4. Results

To incorporate pertinent control variables into our analysis, we employed a rigorous statistical evaluation of the results, leveraging the probit estimation model.

Table 4 delineates a series of five probit estimations pertaining to the WVS generalized trust query. The dependent variable is assigned a value of 1 for respondents who deem individuals trustworthy and a value of 0 for those holding a different belief. Throughout these regressions, variables were progressively integrated into the model. The initial model (Model 1) solely incorporates the age variable. Model 2 encompasses both age and age^2, probing a potential nonlinear age effect. Model 3 augments the analysis with gender and education variables. Subsequent models, 4 and 5, integrate income alongside other cultural and demographic dimensions. The concluding model (Model 5) amalgamates all relevant explanatory variables. The models showcased were selected for their significance and relevance from a broader set of tested models.

As seen in model 1, when other characteristics of respondents are not taken into consideration, the age of the participant is positively correlated with the tendency to trust others (positive coefficient 0.01, at a high level of statistical significance). In Model 2, the analysis adopts a nonlinear paradigm with respect to age, incorporating a variable equated to the square of the participant's age (age^2). The empirical findings from this model indicate a waning of trust during the early stages of adulthood, followed by an increase in the later years. The trust nadir, as inferred from this model, is situated around the age of 32. Scrutinizing Models 3 through 5, no gender-based differences of statistical significance were identified concerning the propensity to exhibit a positive orientation towards generalized trust.

Models 4 and 5 elucidate that both educational attainment and income levels (barring the uppermost decile) exhibit a positive correlation with the likelihood of possessing a favorable disposition towards generalized trust. Concurrently, these models suggest that individuals with offspring tend to harbor a more skeptical perspective on generalized trust.

Pertaining to ethnic and cultural attributes, Models 4 and 5 indicate that individuals identifying as African-American, as well as households predominantly communicating in Spanish, generally exhibit diminished trust levels in comparison to their counterparts with analogous characteristics. In the realm of religious affiliations, the aforementioned models highlight that individuals self-identifying as Protestants are inclined towards a more favorable stance on generalized trust, relative to individuals of other religious denominations possessing similar attributes.

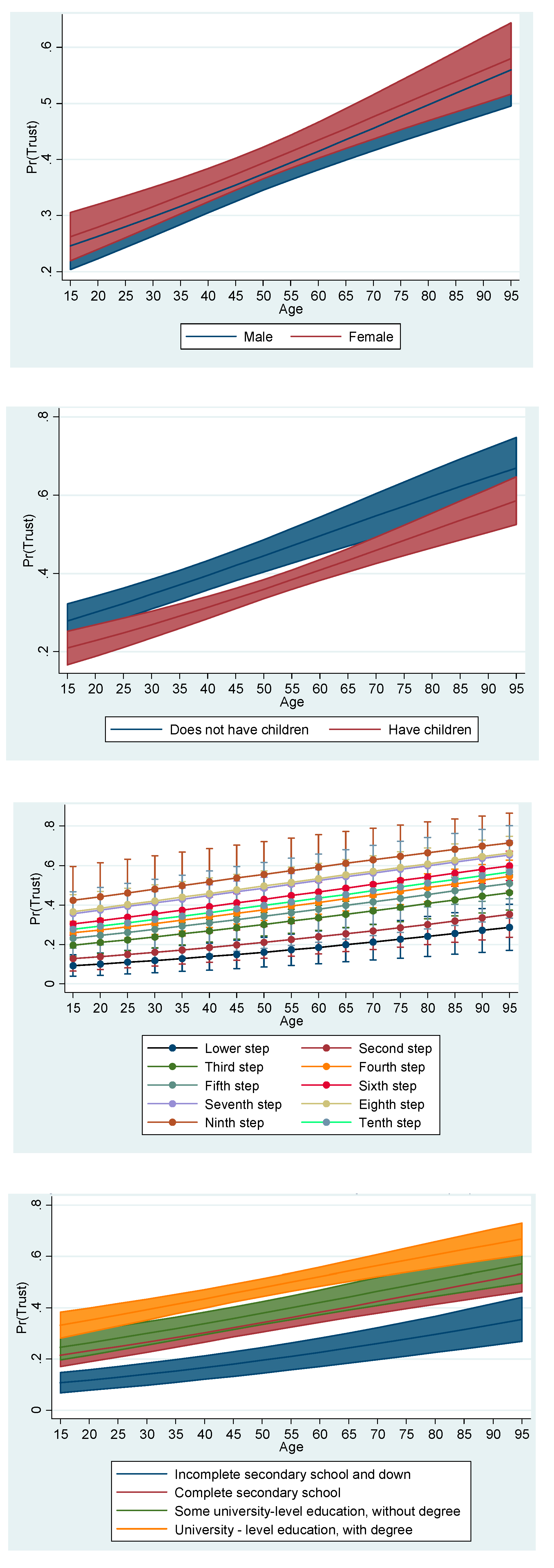

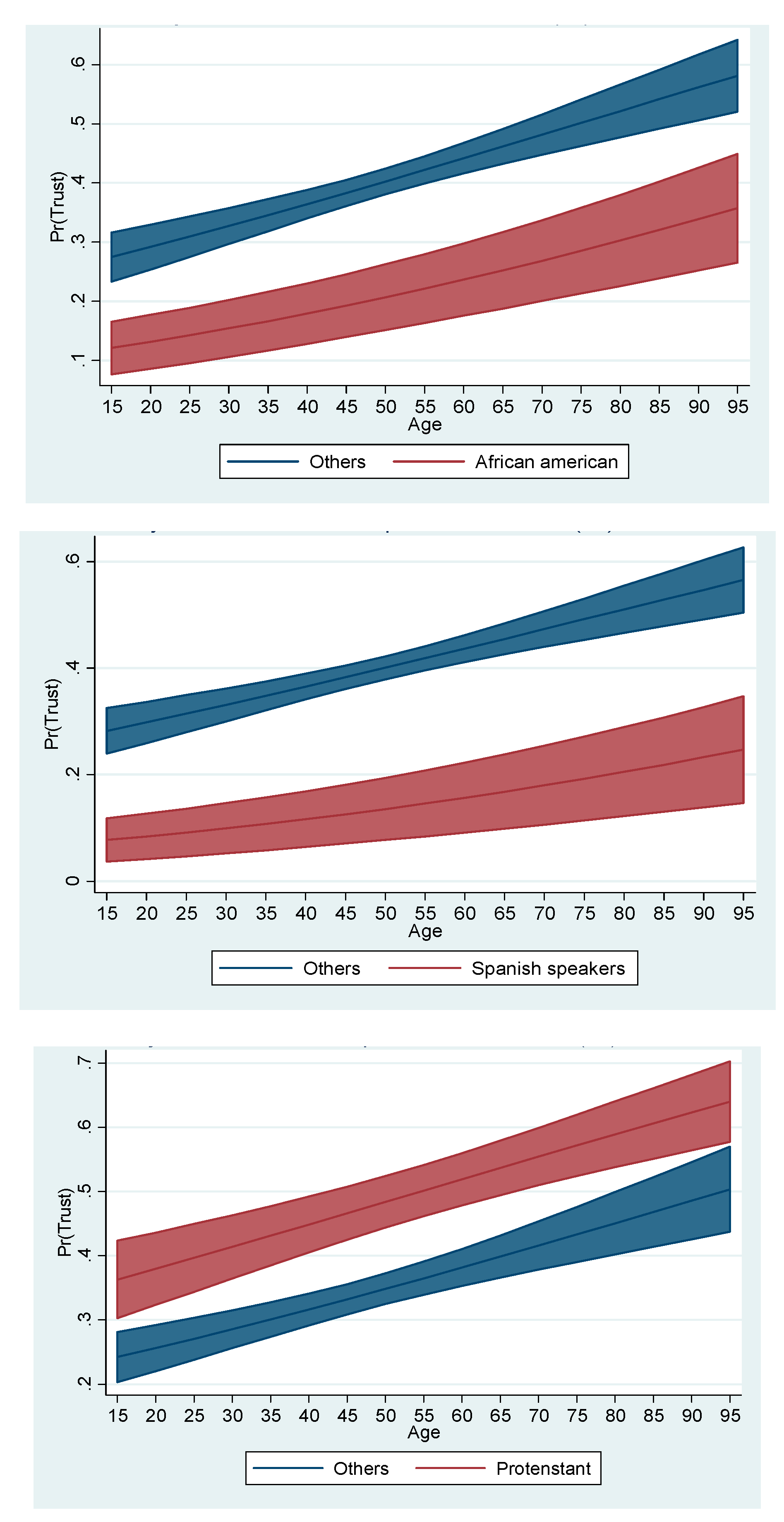

Graphical representations derived from a rudimentary probit analysis (incorporating factors such as age, gender, educational attainment, income bracket, parenthood status, African-American participants, Spanish-speaking households, and Protestant affiliation as determinants for the generalized trust query) can be found in

Appendix A. The outcomes from these elementary analyses align closely with the findings of the more comprehensive multivariate examination.

The outcomes revealed a statistically significant association between age and generalized trust. Both rudimentary and multivariate models underscore a pronounced inclination among the elderly towards positive perceptions of general trust. These observations align with prior research methodologies delineated in the literature review section, reinforcing the notion that older individuals generally exhibit a heightened propensity to trust others compared to their younger counterparts. Furthermore, the results resonate with preceding studies highlighted in the literature review, suggesting a connection between cultural attributes and social trust.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In the present manuscript, we explored perceptions of generalized trust across various age demographics, utilizing the WVS survey data from the United States. The research identifies a linkage between age and social trust. An examination of the generalized trust query within the WVS questionnaire reveals that trust levels when factoring in other influential variables, vary among age cohorts. The analytical outcomes indicate that, when accounting for all other pertinent variables, younger individuals generally exhibit a diminished trust propensity compared to their older counterparts.

The results pertaining to the association between generalized social trust and factors such as educational attainment and income underscore a positive correlation, echoing the conclusions of prior studies (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Hamamura, 2012; Knack and Keefer,1997; Putnam, 2000). The inclusion of additional explanatory variables in the model yields intriguing insights, highlighting that facets of individual identity, linguistic background, and ethnicity emerge as potent determinants in shaping trust disparities among diverse social factions within the United States. Consequently, this research provides compelling evidence suggesting that minority and immigrant-dominated groups exhibit markedly lower trust levels compared to the predominant demographic in the United States. Such observations align with existing literature positing that groups perceiving discrimination may harbor diminished trust levels, stemming from ingrained societal perceptions of injustice (Brockner & Siegel, 1996).

In the context of religious affiliations, the observation that Protestants in the United States exhibit a higher propensity to trust others underscores the influence of cultural nuances on generalized trust levels, corroborating the assertions of previous investigations (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013a; Bjørnskov, 2012; Delhey and Newton 2005; La Porta et al.,1996; Zak and Knack, 2001).

While many preceding studies exploring the relationship between age and trust have relied on smaller samples and restricted age demographics, the current research employs a comprehensive and diverse sample drawn from the broader populace, encompassing a vast spectrum of age categories and individual attributes. As such, the applicability and robustness of these findings to the broader American society are reinforced.

Given that trust is intertwined with trustworthiness and social experiences, it can be inferred that these reduced trust levels are not merely anomalies but are reflective of the broader societal milieu in the US. Such observations underscore the need for a comprehensive analysis of the nation's social fabric and the inherent dynamics that shape it.

The observation that the elderly exhibit a heightened propensity to trust others warrants attention in the formulation of pertinent social and public policies. Within the realm of service provision and goods consumption, it is imperative for society to ensure that such trusting inclinations are not exploited to the detriment of senior citizens. Conversely, the diminished trust levels observed among younger individuals, who are at the zenith of their socio-economic engagements, could potentially impede the efficacy of economic endeavors and social exchanges. Hence, there's a pressing need to advocate for policies that bolster trust and trustworthiness within the younger demographic.

The inherent limitations of deriving insights from a singular temporal questionnaire impede a comprehensive exploration into the underlying determinants of variations in social trust across an individual's life trajectory. It is imperative for future scholarly endeavors to investigate the intricate mechanisms underpinning these alterations in trust levels, while also assessing the ramifications of factors such as the aging process, societal changes, cohort implications, and generational idiosyncrasies on trust dynamics. Considering the profound influence of cultural nuances on social trust, the exclusive reliance on United States-centric data constrains the applicability of these findings to nations characterized by divergent cultural paradigms.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Appendix A

Figures of the predictions of a simple probit analysis (age and: gender, education, income, parenthood, African-American, Spanish speaking households, and Protestants as explanatory variables of the generalized trust question).

References

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others?. Journal of public economics, 85(2), 207-234.

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R. and Hoxby, C. (2004 ), ‘Political Jurisdictions in Heterogeneous Communities’, Journal of Political Economy, 112, 348– 96. [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D., & Van Lange, P. A. (2013a). Trust, punishment, and cooperation across 18 societies: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(4), 363-379.

- Balliet, D., & Van Lange, P. A. (2013b). Trust, conflict, and cooperation: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 139(5), 1090. [CrossRef]

- Barefoot, J. C., Maynard, K. E., Beckham, J. C., Brummett, B. H., Hooker, K., & Siegler, I. C. (1998). Trust, health, and longevity. Journal of behavioral medicine, 21(6), 517-526.

- Bayer, Ya'akov M. (2022) Social trust, ethnic diversity, and religious heterogeneity: evidence from Nigeria. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=4162858.

- Bayer, Ya'akov M. (2019) Older Adults, Aggressive Marketing, Unethical Behavior: A Sure Road to Financial Fraud? In Gringarten, H. & Fernández- Calienes, R. (Ed.) Ethical Branding and Marketing: Cases and Lessons. New York. Rutledge Publishing.

- Bayer Ya'akov M., Ruffle Bradely, Zultan Ro'i, Dwolazky Tzvi (2018) Time preferences in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Laurier Centre for Economic Research and Policy Analysis: Toronto.

- Bellemare, C., & Kröger, S. (2007). On representative social capital. European Economic Review, 51(1), 183-202. [CrossRef]

- Berggren, N. and Jordahl, H. (2006) “Free to Trust: Economic Freedom and Social Capital,” Kyklos 59(2): 141–169. [CrossRef]

- Berggren, N., Elinder, M., & Jordahl, H. (2008). Trust and growth: a shaky relationship. Empirical Economics, 35(2), 251-274. [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. (2009). Social trust and the growth of schooling. Economics of education review, 28(2), 249-257. [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How does social trust affect economic growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346-1368.

- Brandt, M. J., & Henry, P. J. (2012). Psychological defensiveness as a mechanism explaining the relationship between low socioeconomic status and religiosity. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22(4), 321-332. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, M. J., Wetherell, G., & Henry, P. J. (2015). Changes in income predict change in social trust: A longitudinal analysis. Political Psychology, 36(6), 761-768. [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J. and Siegel, P. (1996 ), ‘Understanding the Interaction Between Procedural and Distributive Justice’, in R.M. Kramer and T.R. Tyler (eds), Trust in Organizations, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA; 390– 413.

- Brown, M. and Uslaner, E. M. (2005) ‘Inequality, Trust, and Civic Engagement,’ American Politics Research 33(6): 868–894.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American journal of sociology, 94, S95-S120. [CrossRef]

- Cook, K. (2016). Trust. In Ritzer, G., editor, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Cook, K. and Cooper, R. (2003 ), ‘Experimental Studies of Cooperation, Trust, and Social Exchange’, in E. Ostrom and J. Walker (eds), Trust and Reciprocity, Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research, Russell Sage Foundation, New York; 209– 44.

- Delhey, J. and Newton, K. (2005) “Predicting Cross-national Levels of Social Trust: Global.

- Pattern or Nordic Exceptionalism?” European Sociological Review 21(4): 311–327.

- Dilmaghani, M. (2017). Religiosity and social trust: Evidence from Canada. Review of Social Economy, 75(1), 49-75. [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1993). Childhood and society. WW Norton & Company.

- Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., von Rosenbladt, B., Schupp, J., Wagner, G.G. (2003) A nationwide laboratory. Examining trust and trustworthiness by integrating behavioral experiments into representative surveys. Working paper 141. Institute for Empirical Research in Economics. University of Zurich. [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital. The economic journal, 112(483), F437-F458. [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American journal of sociology, 91(3), 481-510. [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). The role of social capital in financial development. American economic review, 94(3), 526-556. [CrossRef]

- Hamamura, T. (2012). Social class predicts generalized trust but only in wealthy societies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(3), 498-509. [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2014). Social capital and well-being in times of crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 145-162. [CrossRef]

- Henry, P. J. (2009). Low-status compensation: A theory for understanding the role of status in cultures of honor. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(3), 451. [CrossRef]

- Hough, M. (2004). Exploring elder consumers’ interactions with information technology. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 2(6), 61–66. [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. (2015). A loosening tray of sand? Age, period, and cohort effects on generalized trust in reform-era China, 1990–2007. Social science research, 51, 233-246. [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Data file Version: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

- Jones, G.R., George, J.M. (1998). The experience and evolution of Trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork, Academy of Management Review, 23 (3) 531-546.

- Kandori, M. (1988), ‘Monotonicity of Equilibrium Payoff Sets with Respect to Observability in Repeated Games with Imperfect Monitoring’, Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences (IMSSS) Technical Report No. 523, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

- Kinsella, K., & Velkoff, V. (2001). An aging world [United States Census Bureau, Series P95/01–1]. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- Knack, S. (1999). Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the United States: The World Bank.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112(4), 1251-1288. [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1996) , ‘Trust in Large Organizations’, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 87, 333– 8. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A. (2006). Does equality lead to fraternity?. Economics letters, 93(1), 121-125. [CrossRef]

- Mach, M., Dolan, S., & Tzafrir, S. (2010). The differential effect of team members' trust on team performance: The mediation role of team cohesion. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 771-794. [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of management review, 23(2), 242-266.

- Nannestad, P. (2008) “What Have We Learned about Generalized Trust, If Anything?”.

-

Annual Review of Political Science 11: 413–436.

- Nieminen, T., Martelin, T., Koskinen, S., Simpura, J., Alanen, E., Härkänen, T., & Aromaa, A. (2008). Measurement and socio-demographic variation of social capital in a large population-based survey. Social Indicators Research, 85(3), 405-423. [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. (2007). Social capital, institutions and trust. Review of social economy, 65(1), 29-53.

- Papagapitos, A., & Riley, R. (2009). Social trust and human capital formation. Economics Letters, 102(3), 158-160. [CrossRef]

- Platow, M. J., Foddy, M., Yamagishi, T., Lim, L., & Chow, A. (2012). Two experimental tests of trust in in-group strangers: The moderating role of common knowledge of group membership. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 30-35. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World politics, 58(1), 41-72.

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust 1. Journal of personality, 35(4), 651-665. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of management review, 23(3), 393-40. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. A. (2007). Psychological foundations of trust. Current directions in psychological science, 16(5), 264-268.

- Stolle, D. (1998). Bowling together, bowling alone: The development of generalized trust in voluntary associations. Political psychology, 497-525.

- Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. G. (2007). Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games and Economic behavior, 59(2), 364-382. [CrossRef]

- Tanis, M., & Postmes, T. (2005). A social identity approach to trust: Interpersonal perception, group membership and trusting behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(3), 413-424. [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P. A. (2015). Generalized trust: Four lessons from genetics and culture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 71-76.

- Wasik, J.F. (2000).The fleecing of America’s elderly. Consumers Digest, 39(2), 77-83.

- Yamagishi, T. (2011). Trust: The evolutionary game of mind and society. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Zak, P. J., & Knack, S. (2001). Trust and growth. The economic journal, 111(470), 295-321.

| 1 |

The issue of elderly fraud and coping with it is of paramount importance in light of the accelerated increase in the elderly population, the increase in life expectancy in Western society (Kinsella and Velkoff, 2001), and the predictions that economic scams against elders are likely to increase due to the increase in the population and the concentration of capital in the hands of this population (Wasik, 2000). |

| 2 |

Hu (2015) conducted extensive research on the subject in China. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).