1. Introduction

Deep Neural Networks have achieved promising performances in many domains including computer vision and natural language processing. However, there have been a lot of adversarial attacks that can fool the deep learning models [

1]. Adversarial robustness is thus critical in real-world scenarios because deep learning models, when deployed in practical applications, can be vulnerable to such maliciously crafted inputs (i.e., adversarial examples) designed to deceive or mislead them. These adversarial attacks can have severe consequences, especially in safety-critical systems such as autonomous vehicles, medical diagnosis, or financial systems. Ensuring adversarial robustness is critical to maintaining the integrity, safety, and reliability of AI-driven systems in diverse real-world environments.

Consequently, there has been an active research effort to improve the adversarial robustness of recent neural models. In the field of computer vision, adversarial examples (AEs) are obtained by perturbing the original image to introduce small noises that are difficult to discern by human eyes. Adversarial attacks are designed to cause misclassification of the model by creating these AEs, and adversarial defenses are designed to make the model more robust so that it can classify well even when these AEs are mixed in the input. There are many types of adversarial attacks, and one popular technique is to add noise to an image based on gradients (FSGM, PGD, etc.) [

2,

3,

4]. Other methods include generating AEs that minimize a loss function over the input [

5], changing only one of the most critical pixels in the image [

6], and combining multiple methods of creating AEs [

7]. The effectiveness of the attack usually depends on the value of the parameter

, which controls the amount of noise added to images.

Adversarial defense strategies to combat these attacks have also been actively studied. Representative areas include adversarial training [

2], which uses AEs together to train a model, and image denoising, which tries to remove noise from the input AEs [

8,

9]. Adversarial training involves learning AEs together during training, which enables the given classification model to learn the distribution of AEs and thus become robust to adversarial attacks. Adversarial defense strategies to combat these attacks have also been actively studied. Representative areas include adversarial training [

2], which uses AEs together to train a model, and image denoising, which tries to remove noise from the input AEs [

8,

9]. Adversarial training involves learning AEs together during training, which enables the given classification model to learn the distribution of AEs and thus become robust to adversarial attacks. Image denoising aims to restore the AEs as close as possible to the original image by removing the noise in the image, and among them, adversarial purification aims to remove the noise by assuming that the noise is definitely an adversarial purturbation caused by adversarial attacks. However, both methods have limitations in that their robustness performance decreases with different types of attacks, and their accuracy for normal inputs decreases.

In this paper, we propose a novel purification technique that can improve adversarial robustness. The main idea of the proposed method is to transfer the knowledge of two Convolutional Autoencoder [

10] models (one with adversarially trained and the other with normally trained) to a student model through ensemble knowledge distillation [

11]. Convolutional Autoencoder is an image-friendly structure that replaces MLP (multi-layer perceptron) with Convolutional layers in the original MLP-based Autoencoder. It has shown good performance in image restoration and generation because it can capture the local features and spatial structures of images better than MLP. Using this structure as our base model, the knowledge of the adversarially trained teacher model (AT) and the normally trained teacher model (NT) is transferred to the student (purification) model by ensemble knowledge distillation, where the ability to remove the added noise is learned from the AT teacher and the ability to restore the features of the original image is learned from the NT teacher.

We measure the performance of the proposed purifier on a widely utilized benchmark dataset. Specifically, the purified images were fed into a pre-trained classification model to evaluate whether it can accurately predict the class; the better the purification ability, the higher the classification accuracy of the model. The experimental results show that the proposed purifier can indeed prevent accuracy degradation when classifying the original image, and is robust to both the attacks used in training and the attacks not used in training. An ablation study was conducted to verify the effectiveness of the teacher models used in knowledge distillation, and the results showed that the student model using both teacher models as proposed outperformed the other alternatives.

The rest part of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we highlight existing methodologies regarding adversarial training and adversarial purification. In section 3, we introduce our novel adversarial purification method. In section 4, we report the experimental settings and results, demonstrating its efficacy and superiority. Finally,

Section 5 concludes our study.

2. Related Work for Adversarial Defense

This chapter introduces two representative approaches in the context of adversarial defense: adversarial training and adversarial purification. Our work is in line with the latter category.

2.1. Adversarial Training

Adversarial Training involves training a model on adversarial examples (AEs) along with the normal training data. The idea is to expose the model to adversarial attacks during training, so it can learn to resist them. Formally, adversarial attacks manipulate an original image

x into the adversarial example

using the following method:

where

indicates the adversarial noise to be injected. The strength of the attack is controlled by ensuring that the

norm of the noise does not exceed a hyper-parameter,

. The noise introduces subtle changes to the original image that are imperceptible to the human eye [

12]. Various adversarial attacks have been developed over the years. For example, Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) [

2] creates AEs by adding a perturbation in the direction of the gradient of the loss with respect to the input data. Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) [

3] is an iterative version of FGSM, which applies the perturbation step multiple times, each time projecting the adversarial example back into a valid input space. Carlini & Wagner (CW) [

5] attack is a more sophisticated optimization-based approach that aims to find the smallest perturbation necessary to induce misclassification, often resulting in more subtle changes and thus challenging AEs than the aforementioned two methods. In addition, it minimizes the distance of the original image from the corresponding AE, making it more likely to be misclassified, using a distance function, such as

, as an objective.

AdvProp [

13] enhanced robustness of the model by adversarial training using a minibatch consisting solely of normal data as well as a supplementary minibatch consisting of PGD-generated AEs. The AEs in the supplementary minibatch have different underlying distributions than normal examples, which helps to mitigate the issue of distribution mismatch and makes it easier for the model to learn valuable features from both clean and adversarial domains. RoCL (Robust Contrastive Learning) [

14] proposes a novel adversarial training approach without the need for labeled data. It uses instance-wise adversarial attacks and a contrastive learning framework to maximize the similarity between transformed examples and their adversarial perturbations. [

15] explores adversarial training with imperfect supervision, specifically with complementary labels (CLs), and proposes a new learning strategy using gradually informative attacks to address the challenges of this setting. The authors aim to reduce the performance gap between adversarial training with ordinary labels and CLs (such as noisy or partial labels).

2.2. Adversarial Purification

Adversarial purification is a preprocessing technique that removes noise before the classification model receives input images, resulting in clean images. It does not require model modification or additional training, preserving the unique features and performance of each model. The concept of adversarial purification was first introduced by the authors of PixelDefend [

16]. This method trains a PixelCNN [

17] as a purifier by making small changes to input images to return AEs to the distribution of original dataset. However, because PixelDefend makes changes at the pixel level of images, which involves pixel-by-pixel operations, which in turn increases computational overhead. The authors of [

18] propose to improve the purification performance by training an Energy-Based Model (EBM) with a score function trained by Denoising Score-Matching (DSM).

Purification based on Generative Adversarial Nets (GAN) [

19] has also been studied to purify AEs by training a generator to remove noise and a discriminator to distinguish the purified images produced by the generator from original images [

20,

21]. However, the training of GANs is inherently unstable, and there are vulnerabilities in the latent space that can be exploited by adversarial attacks to produce wrong images[

22]. NRP [

23] uses a similar idea to GANs to train a purifier. The purified image is passed through a “critic” network, which acts as a discriminator, and a feature extractor. The loss of the feature extractor is defined as the distance between the AEs and the original images. It is trained to minimize the loss of the critic network as well as to maximize the loss of the feature extractor, and noise is generated based on the loss of the feature extractor and added to the input image. SOAP [

24] simultaneously performs the main task of classification and auxiliary tasks to train a purifier, where the auxiliary tasks include some widely-used tasks in self-supervised learning, such as data reconstruction and rotation prediction. Other works used autoencoders and VAEs [

25] to remove noise [

26,

27,

28], and employed diffusion models to clean up AEs [

29].

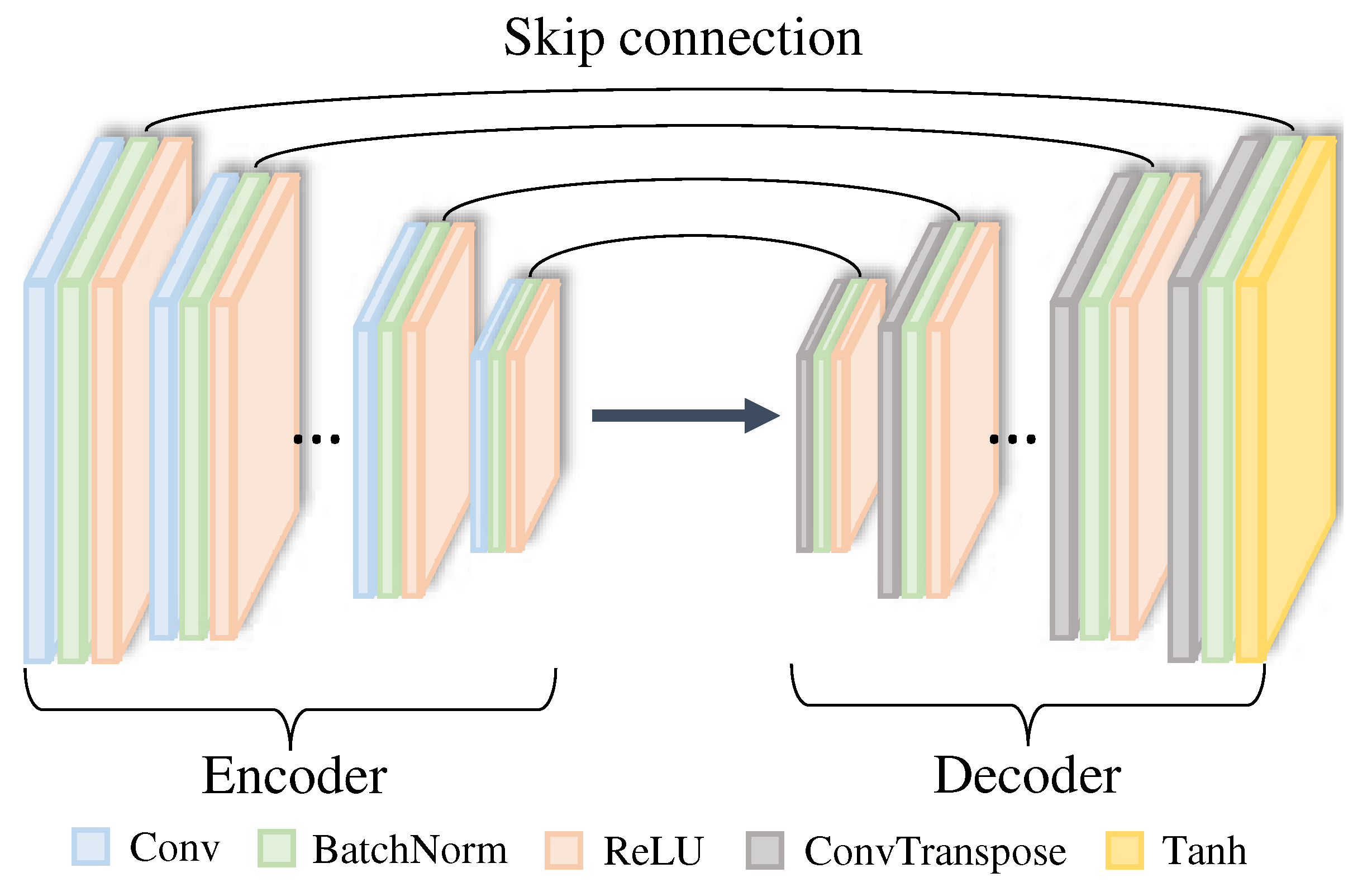

Figure 1.

The structure of the Convolutional Autoencoder used in our work, inspired by [

28].

Figure 1.

The structure of the Convolutional Autoencoder used in our work, inspired by [

28].

3. Method

The overview of the proposed framework for learning purifiers based on knowledge distillation is as follows. First, we train two Convolutional Autoencoder-based teacher models with the same structure. One is trained by adversarial training and the other by normal training using original images. The knowledge of the teacher models is then distilled in an ensemble fashion to the purifier (student model). After the knowledge is transferred, the purifier cleans the images affected by various adversarial attacks, and then classifies the purified images with a pre-trained classification model (ResNet56). This classification result is compared to the classification result of the corresponding original image. The closer the results match, the better the purification.

3.1. Base Model: Convolutional Autoencoders

In our work, the two teacher models and the student model in the knowledge distillation framework are based on the same Convolutional Autoencoder structure. An Autoencoder is an encoder-decoder neural structure that compresses the input through the encoder and restores it to its original dimension through the decoder. The bottleneck layer between the encoder and decoder has a low-dimensional latent representation that retains important features of the original input. The decoder aims to produce an output that is as close as possible to the original input based on this latent. Autoencoders have been widely used for tasks such as data generation, super resolution, and data restoration. We believe that autoencoders are also well suited to the task of purification, which is the task of restoring images by removing noise from AEs.

Furthermore, Convolutional Autoencoders are specialized in dealing with image data. Instead of a fully connected network (FCN), a Convolutional layer with local connections is mainly utilized, which can better learn the spatial features of images. Here, the encoder consists of a series of Convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) layers in one block, for a total of 15 blocks. The Convolution layer extracts various features, colors, textures, etc. from images, while the batch normalization layer keeps the distributions within a batch consistent for stable learning. The ReLU activation function mitigates the problem of gradient vanishing. The decoder also consists of 15 blocks, each of which consists of a series of Convolutional Transpose, batch normalization, and ReLU operations. A tangent hyperbolic (Tanh) operation is added to the end of the last block. The latent representation is upsampled by the Convolutional Transpose operation to decode as close to the input image as possible.

Our Convolutional Autoencoder is quite deep, with a total of 30 blocks. This has the advantage of learning a good quality of latent representation, but because of its depth, there is a risk that the gradient may vanish or explode during backpropagation. To avoid this, we make skip connections at the encoder and decoder to convey the gradient flow directly. This also has the effect of helping the decoder to reconstruct images by preventing the loss of information or details that are useful for reconstruction. As a result, the network structure of this study is similar to that of U-net[

30].

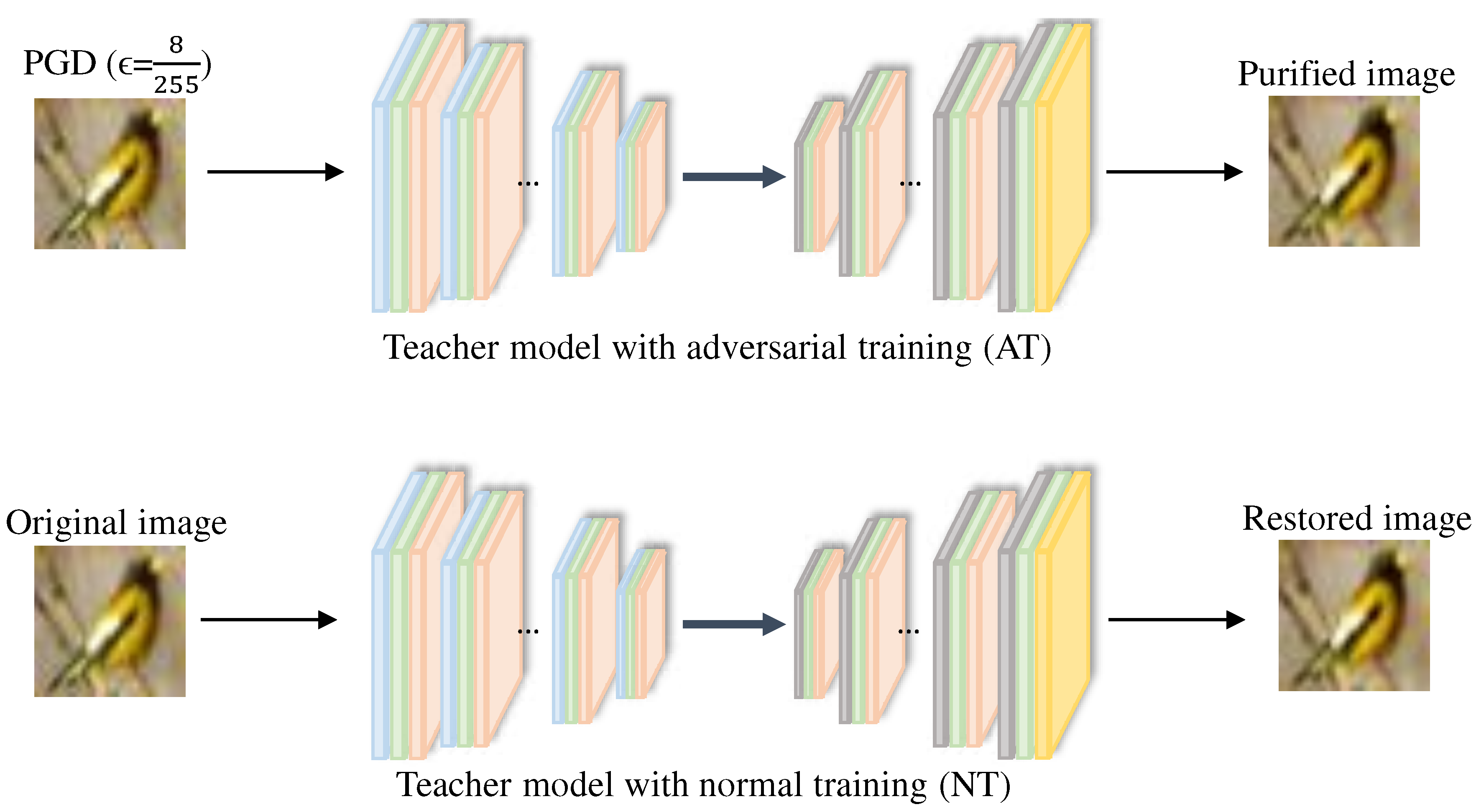

3.2. Teacher Models

Next, we describe the training of two teacher models, as depicted in

Figure 2. The teacher models are of the same Convolutional Autoencoder structure, but one is trained adversarially using the PGD attack (AT teacher model) and the other is trained using the original image (NT teacher model).

The objective function

for training the AT teacher model consists of two loss terms,

and

, as follows:

Here,

n is the number of pixels in an image.

computes the MSE (Mean Squared Error) of the original image

x and the purified image

(

is the adversarial example).

is the adversarial loss function, where

and

denote the output of the classification model with the purified image

and with the adversarial sample

, respectively. These two outputs should be maximized while minimizing the MSE term for training the AT teacher model.

Next, the NT teacher model is trained to minimize the difference between the restored image and the original image. For this, the loss function

uses the mean square error as shown below:

where

is the image restored by the NT teacher model.

As a result, the AT teacher model learns to remove noise by restoring the original images from the adversarial images, and the NT teacher model learns to restore original images by extracting the important features. The respective abilities of the two teachers are distilled to a purifier (student model).

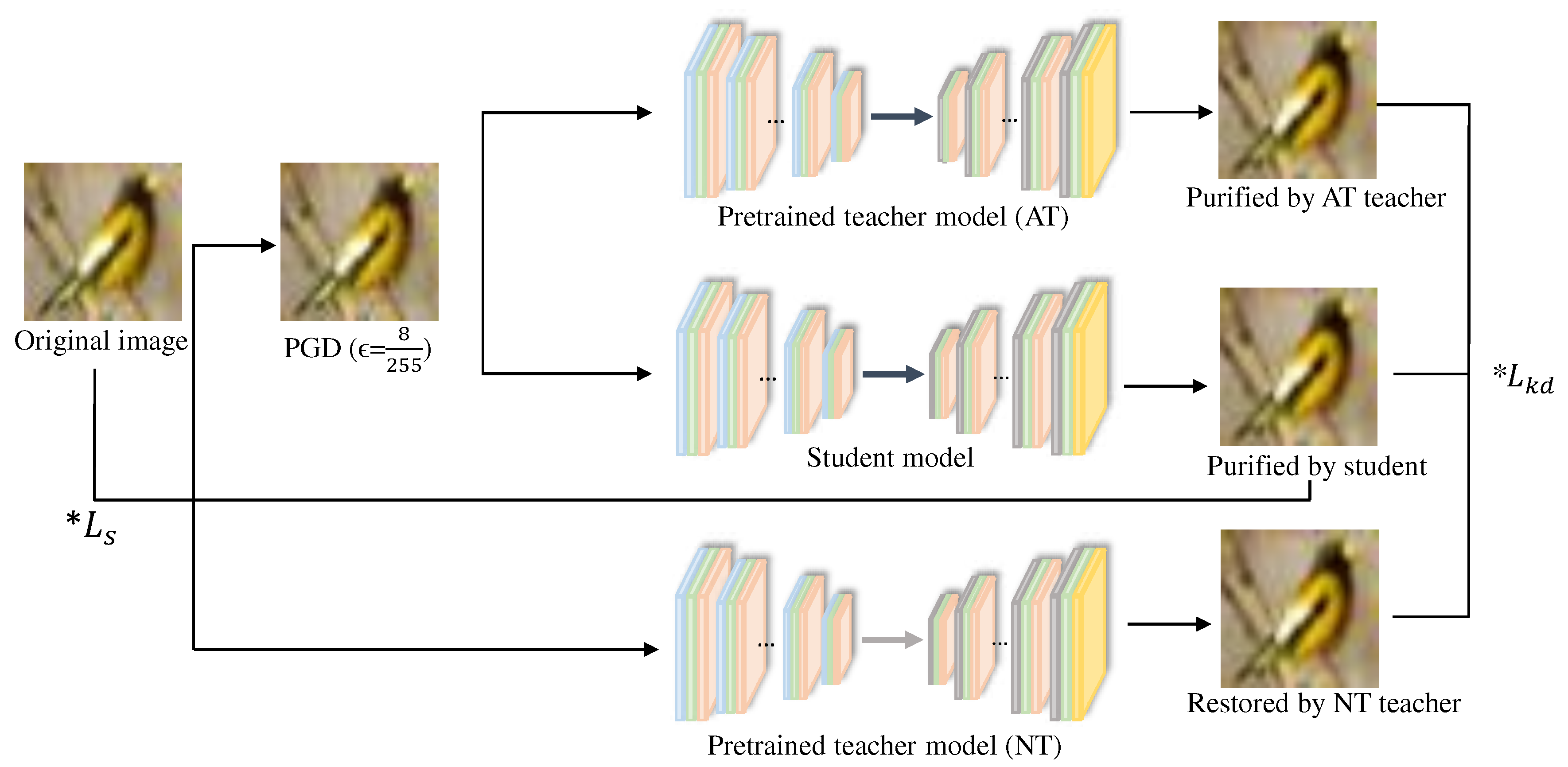

3.3. Training Purifier via Knowledge Distillation

We next build a purifier model as a student to distill the knowledge of the two previously trained teacher models. The purifier also uses a Convolutional Autoencoder with the same structure as the teacher models.

Figure 3 depicts our process of learning a purifier based on knowledge distillation. As we introduced, the AT teacher model is given AEs generated by the PGD attack to purify them, and the NT teacher model is given pure images to restore them. The purifier takes AEs (each denoted by

) as input and tries to remove the noise. Then, the difference between the purified image

and the original image

x is defined as the reconstruction loss function

for our purifier, which is computed as follows:

Another loss function of our purifier, the ensemble knowledge distillation loss function

, consists of the Kullback-Leibler distance and the mean square error between the outputs of multiple teacher models

and student models

, as follows:

where

M is the number of teacher models (in our case,

) and

is each teacher model. The Kullback-Leibler divergence function

computes the difference between the output distribution of the teacher model and that of the student model, where each probability distribution is computed by the Softmax function

g.

As a result, the purifier learns the denoising ability and image restoration ability of the two teacher models respectively, and is simultaneously optimized by the Kullback-Leibler divergence and the mean square error, which can reduce both the distribution difference between the student and teacher models and the output image difference. The final loss function

L for training the purifier is configured as follows:

where

and

control the importance of the reconstruction loss

and the knowledge distillation loss

respectively. For simplicity, we assume that the two loss terms have equal importance and set

.

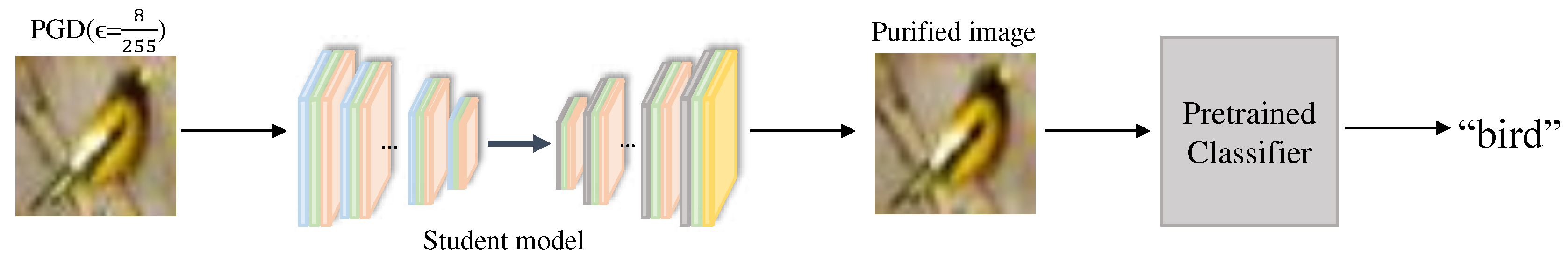

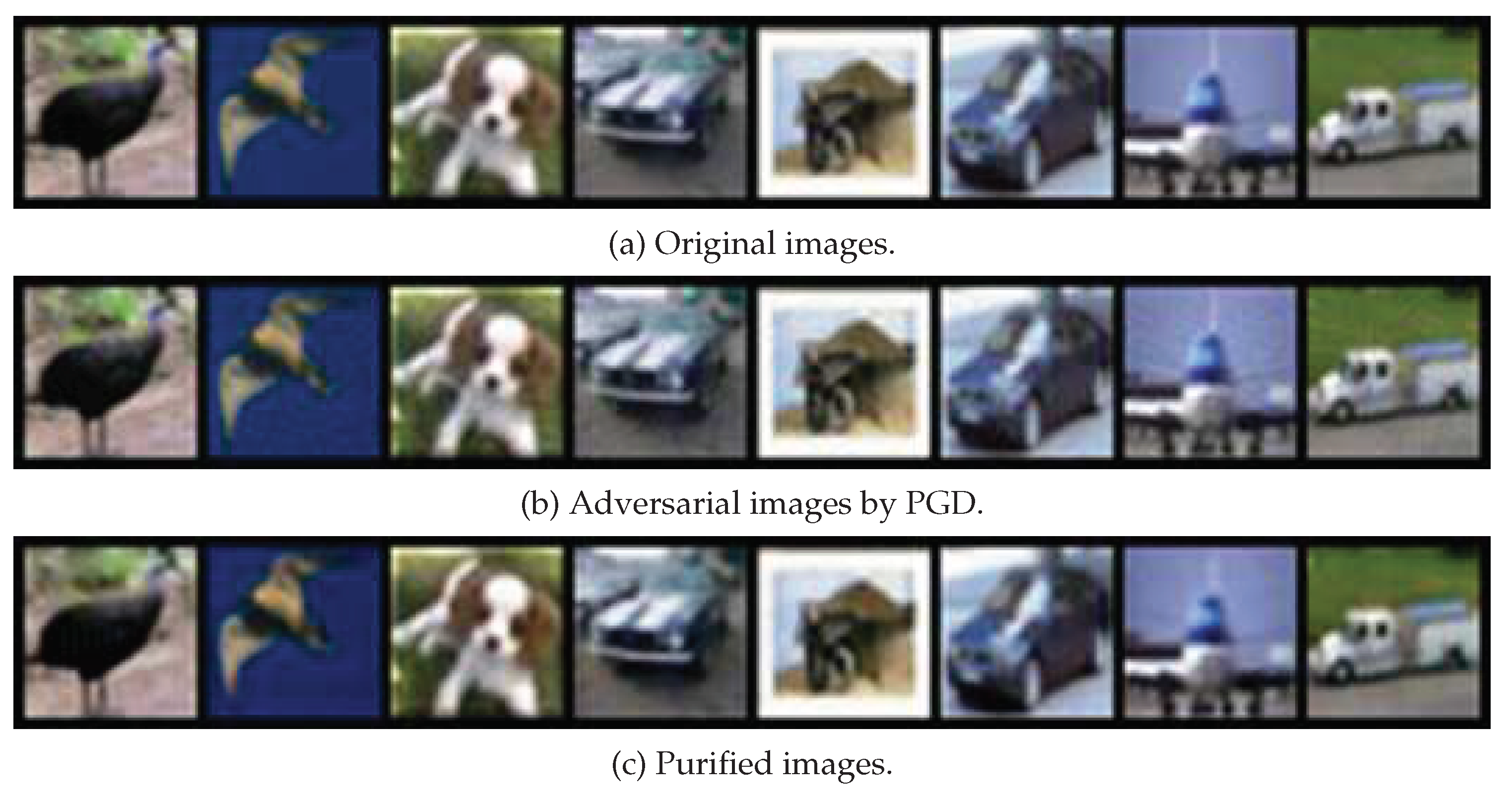

3.4. Purification Process

Figure 4 depicts the overall purification process. After training with ensemble knowledge distillation, the purifier is able to cleanse the AEs generated by various attacks

1 to output purified images (see

Figure 5 for an example of images actually purified by our method). We feed the purified images into a pre-trained classification model (ResNet [

31] is used) to classify them. If the classification result is the same as the classification result of the corresponding original image, we can say that the purification is successful.

4. Evaluation

4.1. Settings

We used CIFAR-10

2, which is a collection of 60,000

color images (i.e., each image is a 3-dimensional array of size

, where the third dimension represents the RGB color channels.) in 10 classes, with 6,000 images per class. There are 50,000 training images and 10,000 test images. The dataset is divided into five training batches and one test batch, each containing 10,000 images. The test batch contains exactly 1,000 randomly selected images from each class. The 10 different classes represent airplanes, cars, birds, cats, deer, dogs, frogs, horses, ships, and trucks. These classes are mutually exclusive, meaning an image can only belong to one class.

In our training, we used a batch size of 128, a learning rate of 0.01, and the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) optimizer. The teacher model was trained for 100 epochs, while the student model was trained for 40 epochs. In the test scenarios, we used five different adversarial attacks: PGD, FGSM, BIM, CW, and AA. PGD, FGSM, and BIM generate noise using gradients which are then added to the input images. FGSM adds noise once, while PGD and BIM add noise iteratively to the images. Specifically, PGD generates noise based on the gradient from the adversarial sample produced in the previous iteration, while BIM consistently computes the gradient from the original input image. Consequently, when the iteration counts are equal, the magnitude of the noise produced by BIM is greater than that produced by PGD. The value of for each attack is set to by default. However, for PGD, since the value of was also used to train our purifier, we used an additional value of , which was not used in the training. We name them PGD8 and PGD16, respectively. For PGD and BIM, we used (step size) of and the iteration number of 20. For CW, we used as the distance function, 40 as the iteration number, and Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01.

4.2. Results and Analyses

First, to evaluate the superiority of our proposed purifier, we purified the AEs generated by the adversarial attacks described above, and then fed the purified images into a pre-trained classification model, ResNet56, to measure the classification accuracy. The accuracy of this classification model on CIFAR-10 is 89.46%. We employed NRP [

23] and SOAP [

24] as baseline purifiers for comparison.

Table 1 reports the experimental results. The proposed purifier generally performed satisfactorily against the gradient-based attacks PGD, FGSM, BIM, and AA. However, it performed slightly worse than SOAP against the PGD16

and the BIM attacks, which add slightly stronger noise than PGD8 which was used for training. We also observed that our purifier did not perform well on samples subjected to CW attacks, which is likely due to the fact that CW is a different type of attack than the gradient-based attack used in the adversarial training of the AT teacher model.

Next, we performed an ablation study.

Table 2 reports the results. The last row of the table is the proposed method (training two teacher models, AT and NT, and distilling their knowledge to our purifier model), and the two rows above it are versions of distilling the knowledge of only one teacher model, AT or NT, to the purifier, respectively. Finally, the first row is a purification method using only adversarial training without knowledge distillation.

The experimental results show that the proposed method generally performs best, and that using only one of the two teacher models or no knowledge distillation leads to lower performance. In particular, distilling the knowledge of the NT teacher model resulted in good performance, which suggests that the knowledge of image restoration is helpful in the purification task. However, the NT teacher model’s knowledge alone was not sufficient to improve adversarial robustness of the student model, and we found that ensemble knowledge distillation from both AT and NT teachers was most effective.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a novel adversarial purification framework for improving the robustness of deep neural networks against adversarial attacks. Our approach utilizes a convolutional autoencoder to capture image features and spatial structure, and a student model is trained on the purified images using knowledge distillation from two teacher models. Experimental results demonstrate that our proposed method can effectively remove adversarial noise from input images and improve model robustness against both white-box and black-box attacks. Our approach also outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy and robustness. Future work will focus on exploring the effectiveness of our approach on other types of neural networks and datasets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and D.-K.C.; methodology, I.K.; software, I.K.; validation, I.K. and D.-K.C.; formal analysis, I.K.; investigation, I.K.; resources, I.K.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K. and D.-K.C.; writing—review and editing, D.-K.C. and S.-C.L.; visualization, I.K.; supervision, D.-K.C. and S.-C.L.; project administration, D.-K.C. and S.-C.L; funding acquisition, S.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the DGIST R&D program of the Ministry of Science and ICT of KOREA (23-IT-10-03 and 23-DPIC-08) and the Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation(IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No.2020-0-01373,Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program(Hanyang University)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Lai, J.H.; Xie, X. Improving adversarially robust few-shot image classification with generalizable representations. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 9025–9034. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In Artificial intelligence safety and security; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 99–112.

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. 2017 ieee symposium on security and privacy (sp). Ieee, 2017, pp. 39–57. [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Vargas, D.V.; Sakurai, K. One pixel attack for fooling deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2019, 23, 828–841. [CrossRef]

- Croce, F.; Hein, M. Reliable evaluation of adversarial robustness with an ensemble of diverse parameter-free attacks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 2206–2216.

- Silva, S.H.; Najafirad, P. Opportunities and challenges in deep learning adversarial robustness: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.00753 2020.

- Liang, H.; He, E.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, Z.; Li, H. Adversarial attack and defense: A survey. Electronics 2022, 11, 1283. [CrossRef]

- Masci, J.; Meier, U.; Cireşan, D.; Schmidhuber, J. Stacked convolutional auto-encoders for hierarchical feature extraction. Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning–ICANN 2011: 21st International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Espoo, Finland, June 14-17, 2011, Proceedings, Part I 21. Springer, 2011, pp. 52–59.

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. NIPS Deep Learning and Representation Learning Workshop, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial Machine Learning at Scale. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Tan, M.; Gong, B.; Wang, J.; Yuille, A.L.; Le, Q.V. Adversarial examples improve image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 819–828.

- Kim, M.; Tack, J.; Hwang, S.J. Adversarial self-supervised contrastive learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 2983–2994. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, T.; Niu, G.; Han, B.; Sugiyama, M. Adversarial Training with Complementary Labels: On the Benefit of Gradually Informative Attacks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 23621–23633. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kim, T.; Nowozin, S.; Ermon, S.; Kushman, N. PixelDefend: Leveraging Generative Models to Understand and Defend against Adversarial Examples. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Oord, A.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Pixel recurrent neural networks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2016, pp. 1747–1756.

- Yoon, J.; Hwang, S.J.; Lee, J. Adversarial purification with score-based generative models. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 12062–12072.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Samangouei, P.; Kabkab, M.; Chellappa, R. Defense-GAN: Protecting Classifiers Against Adversarial Attacks Using Generative Models. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

- Jin, G.; Shen, S.; Zhang, D.; Dai, F.; Zhang, Y. Ape-gan: Adversarial perturbation elimination with gan. ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 3842–3846.

- Kos, J.; Fischer, I.; Song, D. Adversarial examples for generative models. 2018 ieee security and privacy workshops (spw). IEEE, 2018, pp. 36–42.

- Naseer, M.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Porikli, F. A self-supervised approach for adversarial robustness. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 262–271.

- Shi, C.; Holtz, C.; Mishne, G. Online Adversarial Purification based on Self-supervised Learning. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2014.

- Vincent, P.; Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y.; Manzagol, P.A. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning, 2008, pp. 1096–1103.

- Hwang, U.; Park, J.; Jang, H.; Yoon, S.; Cho, N.I. Puvae: A variational autoencoder to purify adversarial examples. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 126582–126593. [CrossRef]

- Kalaria, D.R.; Hazra, A.; Chakrabarti, P.P. Towards Adversarial Purification using Denoising AutoEncoders. NeurIPS ML Safety Workshop, 2022.

- Nie, W.; Guo, B.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Vahdat, A.; Anandkumar, A. Diffusion Models for Adversarial Purification. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 16805–16827.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

In our experiments, we used a variety of attacks that the student model has not encountered, including FSGM, BIM, CW, and AutoAttack, in addition to the PGD attacks used in the training of the AT teacher model. |

| 2 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).