Submitted:

25 September 2023

Posted:

27 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of 316L stainless-steel samples

2.2. Surface characteristics of 316L stainless-steel samples

2.3. Cell culture

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Surface morphology and roughness of polished 316L stainless steel after immersion corrosion

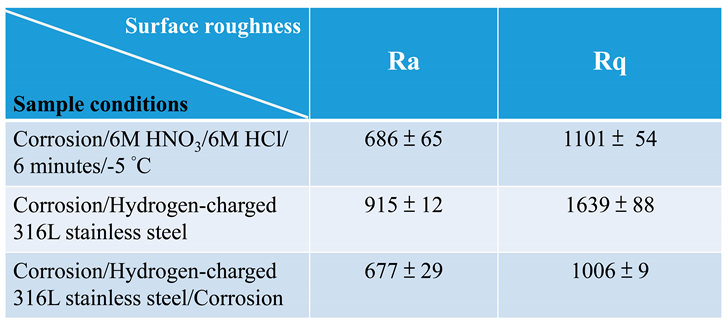

3.2. Surface morphology and roughness of hydrogen-charged 316L stainless steel after immersion corrosion

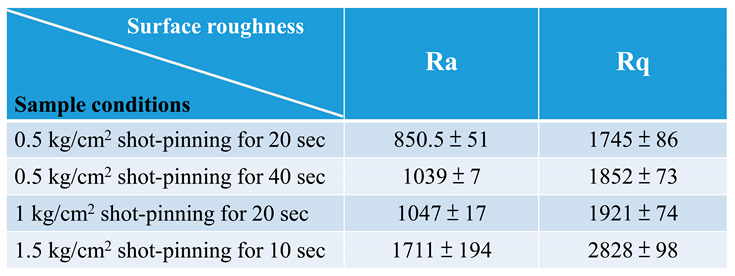

3.3. Surface morphology and roughness of 316L stainless steel after shot peening and subsequent immersion corrosion

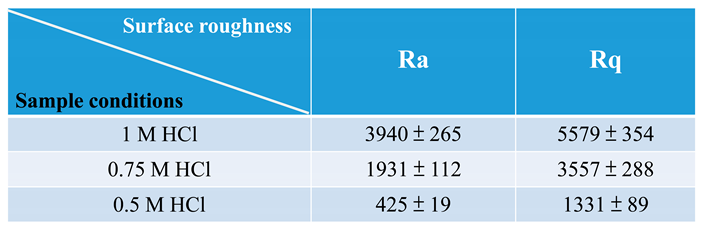

3.3. Surface morphology and roughness of polished 316L stainless steel after electrochemical corrosion

3.4. Raman analysis of 316L stainless steel after various surface treatments

3.5. Spreading and surface morphology of osteoblasts on 316L stainless steel that underwent various surface treatments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Kawashita, M. Current progress in inorganic artificial biomaterials. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Bazaka, O.; Chua, M.; Rochford, M.; Fedrick, L.; Spoor, J.; Symes, R.; Tieppo, M.; Collins, C.; Cao, A.; et al. Metallic Biomaterials: Current Challenges and Opportunities. Materials 2017, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C. M. Reconstructing the human body using biomaterials. JOM 1998, 50, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N. R.; Gohil, P. P. A review on biomaterials: scope, applications & human anatomy significance. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng 2012, 2, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Merola, M.; Affatato, S. Materials for Hip Prostheses: A Review of Wear and Loading Considerations. Materials 2019, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colic, K.; Sedmak, A. The current approach to research and design of the artificial hip prosthesis: a review. Rheumatol. Orthop. Med. 2016, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, H. A.; Sharif, S.; Idris, M. H.; Kamarudin, A. Metallic biomaterials for medical implant applications: a review. Appl. Mechan. Mater. 2015, 735, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, M. B.; Hassan, M. R.; Sahari, B. B. Metallic biomaterials of knee and hip-a review. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 2010, 24, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Goodman, S. B. Current state and future of joint replacements in the hip and knee. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2008, 5, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Ong, J.L.; Oral, E.; Narayan, R.J. Progress in Wear Resistant Materials for Total Hip Arthroplasty. Coatings 2017, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M. A.; Mohammed, A. S.; Al-Aqeeli, N. Wear characteristics of metallic biomaterials: a review. Materials 2015, 8, 2749–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Singh, Y.; Arora, P.; Arora, V.; Jain, K. Implant biomaterials: A comprehensive review. WJCC 2015, 3, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semlitsch, M. Titanium alloys for hip joint replacements. Clinical Mater. 1987, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazic, M.; Kopac, J.; Jackson, M. J.; Ahmed, W. Titanium and titanium alloy applications in medicine. Int. J. Nano Biomater. 2007, 1, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Devgan, S.; Kalyanasundaram, D. Surface alteration of Cobalt-Chromium and duplex stainless steel alloys for biomedical applications: a concise review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, H. A.; Sharif, S.; Kim, D. W.; Idris, M. H.; Suhaimi, M. A.; Tumurkhuyag, Z. J. P. M. Machinability of cobalt-based and cobalt chromium molybdenum alloys-a review. Procedia Manufacturing 2017, 11, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanier, C.; Tabrizian, M.; Yahia, L. H.; Bilodeau, L.; & Piron, D. L. Effect of modification of oxide layer on NiTi stent corrosion resistance. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M. T.; Khan, Z. A.; Siddiquee, A. N. Surface modifications of titanium materials for developing corrosion behavior in human body environment: a review. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B. B.; Beeregowda, K. N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G. C.; Macnair, R.; MacDonald, C.; Grant, M. H. Interactions of orthopaedic metals with an immortalized rat osteoblast cell line. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y. B.; Wang, Z. B.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Z. P.; Lu, J.; Lu, K. Enhanced mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel by pre-forming a gradient nanostructured surface layer and annealing. Acta Materialia 2021, 208, 116773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, T.; Tsuchiyama, T.; Mitsuyasu, H.; Iwamoto, Y.; Takaki, S. Effect of partial solution nitriding on mechanical properties and corrosion resistance in a type 316L austenitic stainless steel plate. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 460, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, M.; Osofero, A.I.; Borri, A. Repair and Reinforcement of Historic Timber Structures with Stainless Steel—A Review. Metals 2019, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvenpää, A.; Jaskari, M.; Kisko, A.; Karjalainen, P. Processing and Properties of Reversion-Treated Austenitic Stainless Steels. Metals 2020, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsiya, C. A review on parameters affecting properties of biomaterial SS 316L. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 20, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordjih, K.; Jouzeau, J. Y.; Mainard, D.; Payan, E.; Delagoutte, J. P.; Netter, P. Evaluation of the effect of three surface treatments on the biocompatibility of 316L stainless steel using human differentiated cells. Biomaterials, 1996, 17, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M. MC3T3-E1 cell response to stainless steel 316L with different surface treatments. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 56, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, F.; Ochsenbein, A.; Traisnel, M.; Busch, R.; Breme, J.; Hildebrand, H. F. (2010). Improving endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation on titanium by sol–gel derived oxide coating. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 92, 754–765. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.; Rajendran, N. Surface characteristics, corrosion resistance and MG63 osteoblast-like cells attachment behaviour of nano SiO 2–ZrO 2 coated 316L stainless steel. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 26007–26016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, A.; Imani, M.; Khorasani, M. T.; Joupari, M. D. Electrochemical and chemical methods for improving surface characteristics of 316L stainless steel for biomedical applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 221, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. J.; Wu, C. Y.; Huang, B. H.; Tsai, C. H.; Saito, T.; Ou, K. L.; Peng, P. W. Surface characteristics and cell adhesion behaviors of the anodized biomedical stainless steel. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocijan, A.; Conradi, M.; Hočevar, M. The influence of surface wettability and topography on the bioactivity of TiO2/epoxy coatings on AISI 316L stainless steel. Materials 2019, 12, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahl, S.; Shreyas, P.; Trishul, M. A.; Suwas, S.; Chatterjee, K. Enhancing the mechanical and biological performance of a metallic biomaterial for orthopedic applications through changes in the surface oxide layer by nanocrystalline surface modification. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7704–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Calderon, M.; Manso-Silván, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Gómez-Aranzadi, M.; García-Ruiz, J. P.; Olaizola, S. M.; Martín-Palma, R. J Surface micro-and nano-texturing of stainless steel by femtosecond laser for the control of cell migration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.; Beshchasna, N.; Pelaccia, R.; Roshchupkin, A.; Yanko, I.; Husak, Y.; Orazi, L. Tailoring surface properties, biocompatibility and corrosion behavior of stainless steel by laser induced periodic surface treatment towards developing biomimetic stents. Surf. Interface 2022, 34, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A.; Kaya, S.; Marzouki, R.; Zhang, F.; Guo, L. Recent advancements in surface modification, characterization and functionalization for enhancing the biocompatibility and corrosion resistance of biomedical implants. Coatings 2022, 12, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. C.; Pang, K. M.; Han, D. W.; Lee, K. H.; Ha, Y. C.; Park, J. W.; Lee, J. H. Enhanced osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on Ti surfaces with electrochemical nanopattern formation. Mater. Sci. Eng, C 2019, 99, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcor, J. D.; Mallein-Gerin, F. Biomaterial functionalization with triple-helical peptides for tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia 2022, 148, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, C. Wen, 1 - Introduction to surface coating and modification for metallic biomaterials, Editor(s): Cuie Wen, Surface Coating and Modification of Metallic Biomaterials, Woodhead Publishing 2015, 3-60.

- Oshida, Y.; Sachdeva, R.; Miyazaki, S. , & Daly, J. Effects of shot-peening on surface contact angles of biomaterials. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med 1993, 4, 443–447. [Google Scholar]

- Bagherifard, S.; Hickey, D. J.; de Luca, A. C.; Malheiro, V. N.; Markaki, A. E.; Guagliano, M.; Webster, T. J. The influence of nanostructured features on bacterial adhesion and bone cell functions on severely shot peened 316L stainless steel. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Choi, W. T.; Johnson, C. T.; García, A. J.; Singh, P. M.; Breedveld, V.; Champion, J. A. Inhibition of bacterial adhesion on nanotextured stainless steel 316L by electrochemical etching. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asri, R. I. M.; Harun, W. S. W.; Samykano, M.; Lah, N. A. C.; Ghani, S. A. C. Tarlochan, F.; Raza, M. R. Corrosion and surface modification on biocompatible metals: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razi, S.; Mollabashi, M.; Madanipour, K. Laser processing of metallic biomaterials: An approach for surface patterning and wettability control. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2015, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, N.; Dongre, G. Laser micro & nano surface texturing for enhancing osseointegration and antimicrobial effect of biomaterials: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 44, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).