1. Introduction

How to prevent the use of Performance and Appearance Enhancing Substances? This question has long accompanied anti-doping research, but before analyzing this important issue, it is necessary to define doping as a pervasive phenomenon in sport and recreational activities, referring to the use of illegal performance-enhancing drugs and methods to improve performance [

1] and the occurrence of one or more of the anti-doping rule violations set (e.g., possession of a prohibited substance or a prohibited method by an athlete or athlete support person; [

2]). Starting from this definition WADA, its correspondent national organizations, and the international Ministries of Health try to provide an accurate and reliable answer. In this sense, an important reflection regards the switch of the paradigm that guides the anti-doping intervention: from a doping prevention paradigm to a promotion of clean sport behavior view [

3]. In order to promote the first perspective, widely developed information-based interventions relying on health education and knowledge regarding doping, such as ATLAS (Athletes Training and Learning to Avoid Steroids; [

4]) and ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise & Nutrition Alternatives; [

5]). Despite the little impact of these programs in reducing the use of prohibited substances and the declared limited effect of education interventions based on knowledge [

6], these types of interventions are implemented still today (e.g., ALPHA program, [

7]; or “Lotta al Doping”,[

8]). Moreover, doping prevention programs are also provided through the so-called “psycho-educative approaches”. Over time, we applied these types of interventions (e.g.,[

9,

10]), focusing on training critical skills to prevent the persuasion of media messages towards doping. In general, media-literacy interventions provided positive effects on media literacy skills, even if a recent meta-analysis reported positive but small effects on attitudes and behavioral intentions [

11]. In order to take into account the new theoretical paradigm based on the promotion of clean sport, and considering the new strategies and technologies, we proposed a digital intervention developing a Serious Game.

1.1. Serious Game and anti-doping research

The term “Serious Game” (SG), also known as “digital game-based learning” [

12], refers to playful and interactive applications with educational objectives that can foster learning, help acquire new skills, and change behavior [

12,

13]. More in general, gamification refers to the use of game design elements in different contexts [

14], and, indeed, SG was widely used in health areas (e.g., psychology, oncology, education; [

12]). The use of this type of technology permits to simulate of an experience in terms of environment or system allowing users to challenge themselves in a less risky or less costly scenario. Another strength in using SG refers to the possibility to try or play again to learning by doing and experiential learning [

15].

Part of the scientific literature in anti-doping research [

13,

16] took into account the innovation in using SG as a learning opportunity that facilitates and stimulates independent and active learning, improves levels of information, and likelihood for persuasion, attitudes and behavior change [

16]. Starting from these considerations, the authors implemented SG programs, such as GAME Project or TARGET, with the aim to transform anti-doping education interventions. Despite the innovative perspective and the positive users’ opinions in terms of usability, enjoyment, and satisfaction [

13], these kinds of interventions did not evaluate the psychological variables that underpin the doping use. Indeed, an important meta-analysis by Ntoumanis and colleagues strongly recommended developing and implementing doping-related interventions based on psychological frameworks [

6].

1.2. The present study

In light of the above and taking into account the gaps in the literature, we implemented a SG intervention to promote clean sport behavior in sport high school students, considered a risky population in using substances to improve sport performance and/or to enhance appearance (e.g., [

17,

18]). Following Ntoumanis’ suggestions [

6], we considered Socio-Cognitive Theory variables [

19] in examining the SG outcomes. In particular, we evaluated how an innovative and technological anti-doping program could influence the critical social-cognitive factors in referring to the decision to use substances, such as, intention to use substances, self-regulatory efficacy to resist social pressure for the use of substances, and moral disengagement. This latter refers to the cognitive process that individuals can apply to deactivate moral self-regulation and disengage from moral norms avoiding, apparently, guilt and/or self-censure, through personal maneuvers by which moral self-sanctions can be disengaged. Specifically, we considered the moral justification (i.e., a person’s detrimental conduct may be deemed acceptable because it serves socially valid or moral purposes); the exonerative comparison (i.e., comparison with more flagrant inhumanities); and the displacement and diffusion of responsibility to remove personal responsibility [

20]. Moreover, we also evaluated the knowledge regarding the anti-doping system, the assumption of substances and/or supplements, and the rules in sport contexts.

A further aim of the present research was to evaluate how and if the scores obtained at the end of the SG could represents the individuals’ internal beliefs, coherently with the answers and the opinions about the doping issues, evaluated using the questionnaires.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

We recruited six Italian sports high schools, and we informed them about the aims of the present research. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, “Sapienza” University of Rome (n. 0001020-28/07/2022). Sport high school students participated in the study prior to written consent (if minors, parents provided consent), and they were recruited using a convenience sampling procedure for the selection of two distinct groups: “intervention group” and “control group” (following the convenience assignment). The “intervention group” is composed of 167 students (37.7% female) who actively participated in SG activities and the “control group”, composed of 112 students (42% female), who only contributing to the questionnaire assessment.

2.2. Intervention and its Implementation

The intervention was developed and coordinated by the University of Rome “Sapienza”, the University of Rome “Foro Italico”, and the University of Milan “La Statale”. The content of SG has been co-designed by sport psychologists, sport scientists, and a computer scientist. With the aim of creating a realistic storyboard related to a credible situation in sport context, a focus group composed of the target population was organized. The SG reported four weeks regarding the everyday life of a track and field athlete who experienced different situations to have the possibility of running in an important competition. The main character interacts with his girlfriend, parents, coach, and teammate with whom he faced different decisions and challenges related to the possibility of using doping substances or supplements. The protagonist had the possibility to make different decisions and, based on them, the final of the story presents different scenarios (e.g., the athlete decides to not use doping and wins the race; the athlete denounces the teammate; the athlete consumes banned substances, etc.). Once we finished writing the storyboard, the computer scientist developed the SG with the support of the graphic designer, voice actors, and the weekly supervision of all the units.

The intervention comprised four 90-min sessions relying on a trained sport psychologist, divided as follows:

First session: the sport psychologist introduced the project and participants answered the questionnaire at the beginning of the intervention (T1).

Second session: the sport psychologist explained the definition of “SG” and how to use the platform, and participants played the SG.

Third session: the sport psychologist described each score the participants obtained at the end of the SG and started a discussion with the participants.

Fourth session: the sport psychologist explained the anti-doping rules and the WADA code, answered all the questions, and participants answered the questionnaire at the end of the intervention (T2).

2.3. Measures

Both groups provided data by answering the same questionnaire on two occasions separated by almost a month. The “intervention group” filled out the questionnaire before and after the intervention sessions and, in addition, obtained SG scores for each Socio-Cognitive Theory variable.

2.3.1. Doping intention

In line with previous studies (e.g., [

21]), the doping intention was measured by asking students to report their doping likelihood considering two hypothetical scenarios, in which they could decide to use illegal substances. The supposed situations simulated two of the most common reasons for consuming banned substances: enhancing performance the day before the most important competition of the season, and aiding recovery from an injury that compromises participation in the most important competition of the season. In both cases, participants reported the likelihood of using doping by answering to three items for each scenario on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all likely”) to 7 (“Very likely”). The internal consistency reliabilities were 0.92 and 0.90 for time 1 and both 0.94 for time 2 in the “intervention group” and “control group” respectively.

2.3.2. Self-regulatory efficacy to resist social pressure for the use of substances

We asked participants to respond to seven items measuring if they felt confident in avoiding social pressure for the use of banned substances. Each item was introduced by the same stem (“How capable do you feel of avoiding the use of prohibited substances…) and presented on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all confident”) to 7 (“Completely confident”; [

22]). The internal consistency reliabilities were 0.93 and 0.95 for time 1 and both 0.96 for time 2 in the “intervention group” and “control group” respectively.

2.3.3. Moral disengagement

The measurement of doping moral disengagement relied on six moral disengagement mechanisms, selected following previous studies (e.g., [

17]). Students answered by reporting their agreement in situations in which the use of doping substances would or should not be condemned (e.g., “Those who use illicit substances in sport are not to be blamed, but those who expect too much from them should”). For each item, participants rated their agreement on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“I do not agree at all”) to 5 (“I completely agree”). The internal consistency reliabilities were 0.39 and 0.75 for time 1 and 0.75 and 0.78 for time 2 in the “intervention group” and “control group” respectively.

2.3.4. Doping Knowledge

Knowledge was evaluated by selecting 10 items from the 40 of the “WADA's Play True Quiz”. This test measures the knowledge in terms of the anti-doping system, choosing for each statement is “True” or “False”, with a total score range of 0 to 10.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive characteristics (i.e., age, gender, type and level of sport) were examined using statistical analysis, means with standard deviations, and percentages, and were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square test as relevant. A series of repeated measures ANOVA were performed for each variable to evaluate differences across time (“time 1” vs. “time 2”) and between study groups (“intervention group” vs. “control group”), and for the interaction between time and study group. Furthermore, model 4 of the PROCESS macro [

23] was selected for mediation analyses, assessing SG score as the mediator in the relations between “time 1” and “time 2” variables scores (i.e., intention, self-efficacy, and moral disengagement). Confidence intervals (95%) were estimated with 10000 bootstrap samples and unstandardized regression coefficients. Effects were considered significant if their confidence intervals did not include zero. All the analyses were conducted using the SPSS software (version 28.0).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive characteristics

The groups' characteristics are reported in

Table 1, showing that there is no significant difference between the “intervention group” and “control group” on age, gender, and sport type, except for sport level.

3.2. Doping intention

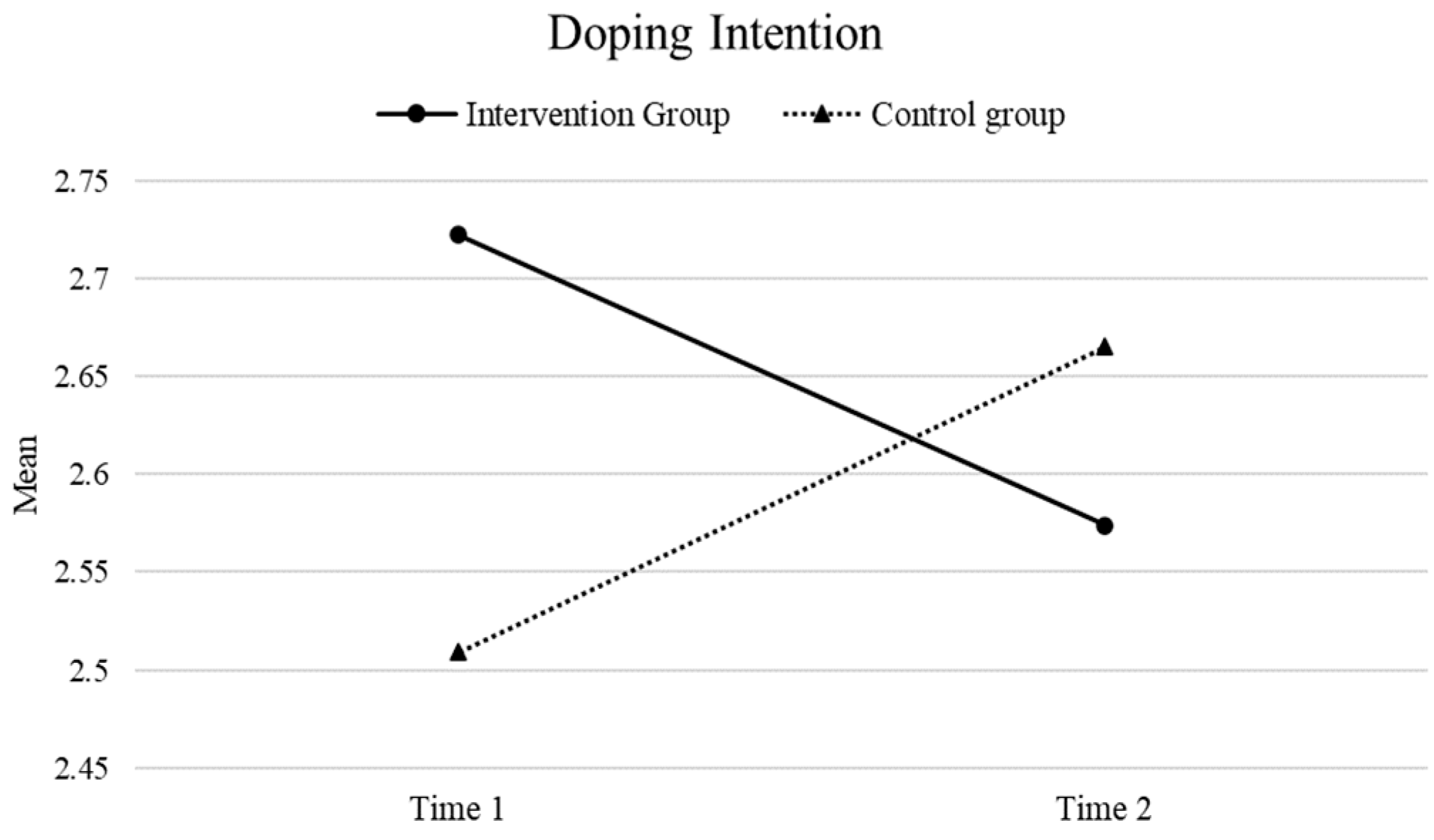

Results of a first repeated-measures ANOVA considering students’ likelihood to use doping as dependent variable revealed a statistically significant “Group by Time” effect [F

(1,272) = 3.89; p = 0.05; partial eta square = 0.014]. As can be seen in

Figure 1, athletes’ intention to doping decreased over time for the “intervention group” [Mean (time 1) = 2.72; SD (time1) = 1.39; and Mean (time 2) = 2.57; SD (time2) = 1.44], and increased over time for the “control group” [Mean (time 1) = 2.51; SD (time1) = 1.37; and Mean (time 2) = 2.67; SD (time2) = 1.47]. However, there were no statistically significant main effects of “Time” [F

(1,272) = 0.003; p = 0.958; partial eta square < 0.001] and “Group” [F

(1,272) = 0.147; p = 0.702; partial eta square = 0.802].

3.3. Self-regulatory efficacy to resist social pressure for the use of substances

A second repeated-measures ANOVA which considered students’ self-efficacy as dependent variable yielded no statistically significant effect for the “Group by Time” interaction (F(1, 272) = 0.004; p = 0.952; partial eta square < 0.001) and the main effect of “Group” (F(1, 272) = 1.632; p = 0.202; partial eta square = 0.006). However, there was a significant main effect of “Time” (F(1, 272) = 10.549; p < 0.01; partial eta square < 0.037). When these effects were more carefully examined via pairwise comparisons, differences emerged across timepoints. The mean levels of self-efficacy significantly decreased over time in both “intervention group” students [F(1,272) = 7.006, p = 0.009; partial eta square = 0.025; Mean (time 1) = 5.52; SD (time1) = 1.54, Mean (time 2) = 5.12; SD (time2) = 1.86] and “control group” students [F(1,272) = 4.168, p = 0.042; partial eta square = 0.015; Mean (time 1) = 5.28; SD (time1) = 1.82, Mean (time 2) = 4.89; SD (time2) = 1.88].

3.4. Moral disengagement

Similarly, a third repeated-measures ANOVA which considered students’ moral disengagement as dependent variable showed no statistically significant effect for the “Group by Time” interaction (F(1, 277) = 1.349; p = 0.246; partial eta square = 0.005) and the main effect of “Group” (F(1, 277) = 1.705; p = 0.193; partial eta square = 0.006). However, there was a significant main effect of “Time” (F(1, 277) = 11.570; p < 0.01; partial eta square = 0.04). A detailed examination of pairwise comparisons yielded a significant effect among “intervention group” students [F(1,277) = 12.697; p < 0.001; partial eta square = 0.045], whereas this pattern did not emerge for their “control group” counterpart [F(1,277) = 2.095; p = 0.149; partial eta square = 0.008]. Over time, “intervention group” students showed a reduction in their average level of doping moral disengagement [Mean (time 1) = 1.768; SD (time1) = 0.51; and Mean (time 2) = 1.60; SD (time2) = 0.62], whereas “control group” students’ moral disengagement decreased to a lesser extent [Mean (time 1) = 1.64; SD (time1) = 0.64; and Mean (time 2) = 1.57; SD (time2) = 0.62].

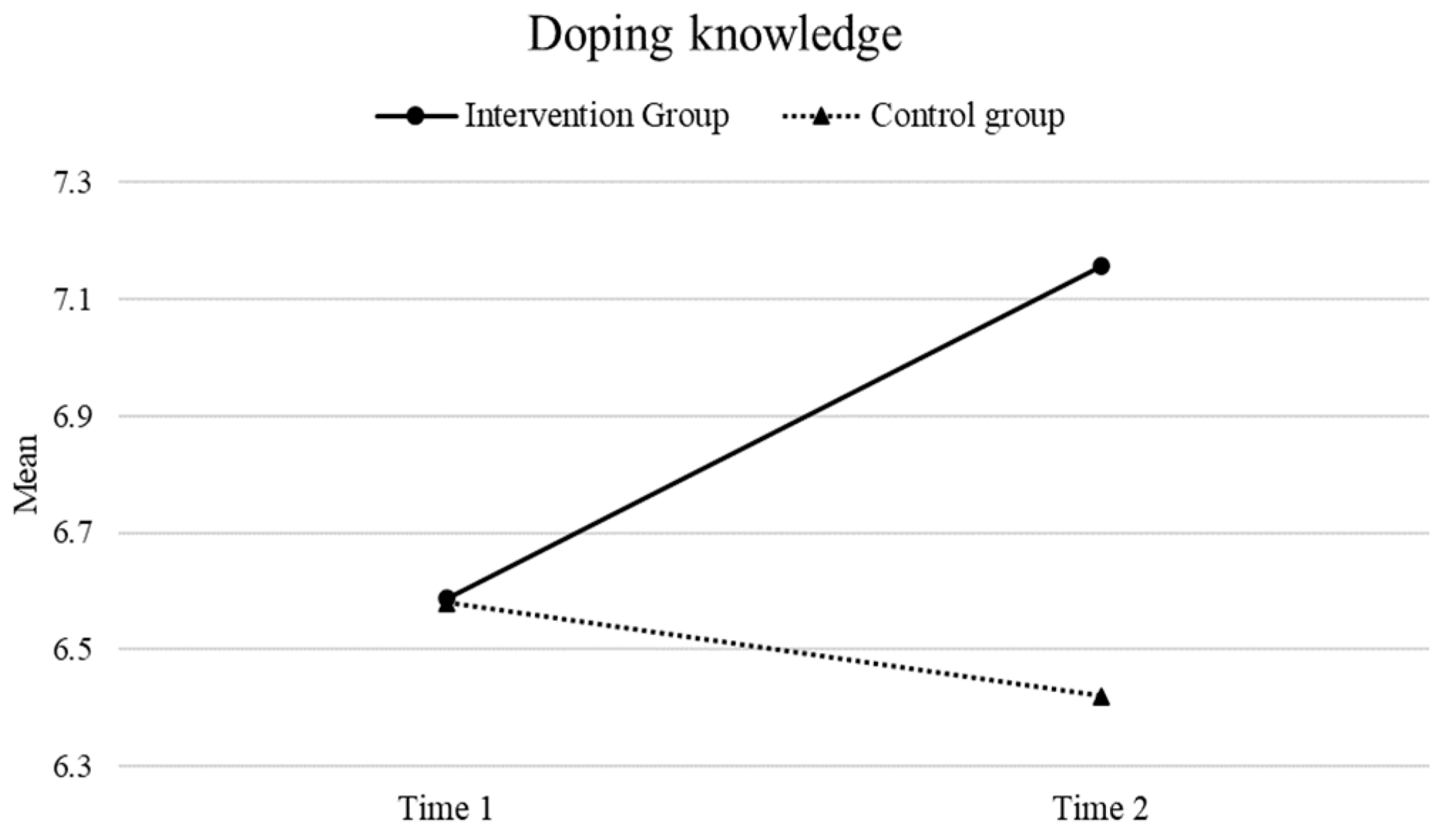

3.5. Doping knowledge

Finally, results of the last repeated-measures ANOVA considering students’ doping knowledge as dependent variable revealed a statistically significant “Group by Time” effect [F

(1,277) = 10.211; p = 0.002; partial eta square = 0.036] and the main effect of “Group” (F

(1, 277) = 5.758; p = 0.017; partial eta square = 0.020). To visualize the “Group by Time” effect,

Figure 2 shows the students’ knowledge mean scores across experimental conditions and across timepoints. Consistent with the figure, athletes’ doping knowledge increased over time for the “intervention group” [Mean (time 1) = 6.59; SD (time1) = 1.37; and Mean (time 2) = 7.16; SD (time2) = 1.38], and decreased over time for the “control group” [Mean (time 1) = 6.58; SD (time1) = 1.74; and Mean (time 2) = 6.42; SD (time2) = 1.92]. Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant main effect of “Time” [F

(1,272) = 3.196; p = 0.075; partial eta square < 0.011].

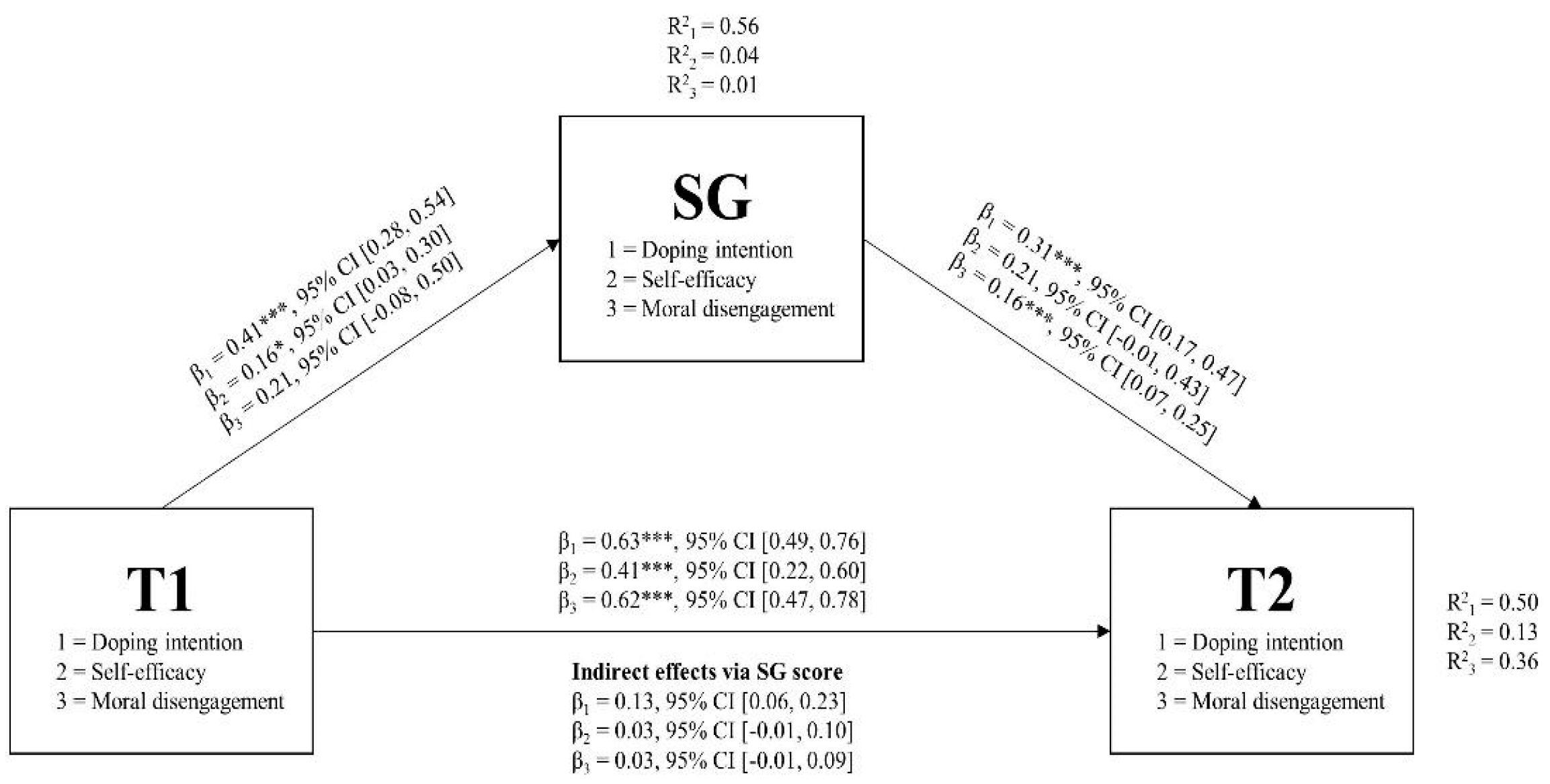

3.6. Mediation analyses

To test whether changes in “intervention group” students’ intention to doping, self-efficacy, and moral disengagement from T1 (i.e., before intervention) to T2 (i.e., after intervention) were mediated by SG score collected during the intervention (i.e., second session), mediation models were tested separately for each variable.

Figure 3 summarizes the three models’ statistical information. Regarding the direct effects, all variables’ scores collected at T1 significantly and positively predicted their scores collected at T2. All T1 variables’ scores, except for T1 moral disengagement score (β = 0.21, 95% CI: [-0.08, 0.50]), significantly and positively predicted their SG scores. Lastly, all SG scores, except for SG self-efficacy score (β = 0.21, 95% CI: [-0.01, 0.43]), significantly and positively predicted their T2 scores. Regarding the indirect effects, only T1 doping intention score has a significant indirect positive effect on T2 doping intention score via SG doping intention score (β = 0.13, 95% CI: [0.06, 0.23]). Thus, T1 doping intention score positively predicts its SG score that, in turn, positively predicts its T2 score.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to answer the call of WADA regarding the most concerns related to the susceptibility to assume banned substances from young athletes, who could consider doping as a shortcut to achieving sport goals [

24]. Our main intent was to develop an anti-doping intervention that could take into account scientific suggestions, such as overcoming the classical educational programs in favor of psychological ones [

25], focusing on theoretical frameworks (e.g.,[

6]), and evaluating the effects of technological anti-doping interventions (e.g.,[

16]). With these premises in mind, we involved sport high school students to play the Serious Game, i.e., a persuasive videogame with the scope to prepare adolescents to face different situations related to the decisions and the consequences of using banned substances in sport contexts. To evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented intervention, we considered the impact of Socio-Cognitive Theory constructs (i.e., doping intention, self-regulatory efficacy to resist social pressure for the use of substances, and moral disengagement) and doping knowledge, testing the questionnaire’s answer at T1 and at T2 for both intervention and control groups. Moreover, we were interested in evaluating how the SG players’ choices could really represent the students' beliefs regarding doping.

Results showed that the proposed intervention tends to reduce the likelihood of dope in students who took part in the intervention. This aspect is particularly important if we consider that doping intention (e.g.,[

26]), temptation (e.g.,[

27]) or likelihood (e.g., [

21]) are proxies for the doping behavior. Moreover, it is interesting to note that pairwise comparisons allow us to consider relevant changes in moral disengagement construct. In this sense, the intervention seems to have an effect in empowering sport high school students in terms of choices and consequences when they decide to use, or not, banned substances. Also in this case, this result is particularly important, in fact, most of the scientific literature demonstrated how adolescents who declared high levels of doping moral disengagement could predict the assumption of doping (e.g.,[

17]). Indeed, more recently, scholars highlighted the relevance of focusing on moral intervention in order to promote “clean sport behavior” (e.g., to not use doping, [

28]). Based on our results, the proposed intervention was not sufficient to have a significant impact in increasing self-regulatory efficacy to resist social pressure for the use of substances, as we expected. It could be possible to suppose that to obtain a change in a psychological construct that strongly takes into account social aspects, it could be necessary to emphasise social skills, considering also dealing with assertiveness and/or self-esteem. As previously declared, we evaluated not only the Socio-Cognitive Theory variables but also the possible increase in doping knowledge. Findings showed that, although our sample already has different information about doping, indeed they study the history of doping, the rules of WADA, and anti-doping as school subjects in class, and most of them are athletes (n = 86.2%), the intervention has allowed them to acquire more notions.

In regard to the other aim of the present research, we explored how the participants’ decisions, evaluated through the SG scores, could really represent the beliefs of the students with respect to doping issues, consistently to the questionnaires’ answers. As results indicated, the hypothesized mediation models showed that the SG scores seems to be a coherent measure in order to express the participants’ opinions, especially in terms of doping intention. As concerns the non-significant paths related to self-regulatory efficacy and moral disengagement, we could explain these results in both theoretical and statistical points of view. We supposed that regarding these two psychological constructs it could be necessary to extend the measurement during the SG’s questions to better explore these aspects (e.g., creating more dilemmas). Statistically speaking, these paths presumably could have a significant effect trying to increase the number of participants.

4.1. Strengths, limitations and future research

The present research has several strengths. First, for our knowledge, this study is the first structured SG intervention regarding doping issues implemented with sport high school students, a group which is particularly at risk for PAES use [

17]. The SG programs already existed (e.g., GAME Project, [

29]) did not evaluate the effectiveness of this types of technological interventions; in addition, we estimated, through the mediation of the SG score, for the first time, the role and the value of the SG as measure of the participants’ beliefs. These strengths notwithstanding, there exist some limitations that should be noted. First, the investigation was implemented in high school settings, and, as a result, the two samples of sports high school students were not stratified samples. Therefore, findings should not and cannot be generalized to the broader sports high school student population. Secondly, students’ assignment to the two conditions of the program (i.e., “control group”

vs “intervention group”) was not rigorously randomized but was based on the schools’ availability by using a convenience sampling procedure. Moreover, there were methodological concerns that need to be mentioned: the number of students involved in the study and the possible that the finding might be biased and be a function of the school context in which they were nested.

In conclusion, future studies should extend SG interventions to other sport high school and/or to other sport contexts, developing a SG intervention focused on a specific sport or disciplines (e.g., a SG sets in a sport for sport-specific athletes) and/or other populations involved in the sport and doping ambience (e.g., coaches, trainers, parents). Moreover, future research could develop a SG intervention, increasing the specific dilemmas related to each psychological variable, and trying to measure the change of Socio-Cognitive variables along time, through long-term follows up, as recently suggested by [

25].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L., A.Z and F.G.; methodology, F.G, A.C., R.C. T.Z., T.P.; software, V.D.; formal analysis, F.G, A.C., L.M and A.D.M.; investigation, F.G., A.D.M., R.C., D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G., A.D.M., A.C.; writing—review and editing, F.A., L.M., R.C., T.Z.; supervision, A.Z. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health-Section for the Supervision and the Control of Doping and for the Protection of Health in Sport Activities of the Technical Health Committee (Agreement n 2021-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics Committee of the Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, “Sapienza” University of Rome (prot.n.1020; 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. If minors, parents provided consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Italian sport high schools for participating to the present research with enthusiasm and professionalism: “Pacinotti-Archimede” high school in Rome (Italy), “Primo Levi high school in Rome (Italy), “Croce Aleramo” high school in Rome (Italy), “G.B. Grassi” high school in Latina (Italy), “Galileo Galilei” high school in Verona (Italy), “Antonio Rosmini” high school in Rovereto (Italy).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE 2 0 0 9 World Anti-Doping Code. 2009.

- WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE 2021 2 World Anti-Doping Code 2021 World Anti-Doping Code.

- Mortimer, H.; Whitehead, J.; Kavussanu, M.; Gürpınar, B.; Ring, C. Values and Clean Sport. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 533–541. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Elliot, D.L.; Moe, E.L.; Clarke, G.; Cheong, J.W. The Adolescents Training and Learning to Avoid Steroids Program: Preventing Drug Use and Promoting Health Behaviors. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 332–338. [CrossRef]

- Elliot, D.L.; Goldberg, L.; Moe, E.L.; DeFrancesco, C.A.; Durham, M.B.; Hix-Small, H. Preventing Substance Use and Disordered Eating: Initial Outcomes of the ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise and Nutrition Alternatives) Program. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 1043–1049. [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Barkoukis, V.; Backhouse, S. Personal and Psychosocial Predictors of Doping Use in Physical Activity Settings: A Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2014, 44, 1603–1624. [CrossRef]

- Murofushi, Y.; Kawata, Y.; Kamimura, A.; Hirosawa, M.; Shibata, N. Impact of Anti-Doping Education and Doping Control Experience on Anti-Doping Knowledge in Japanese University Athletes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Codella, R.; Glad, B.; Luzi, L.; La Torre, A. An Italian Campaign to Promote Anti-Doping Culture in High-School Students. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Palombi, T.; Mallia, L.; Chirico, A.; Zandonai, T.; Alivernini, F.; De Maria, A.; Zelli, A.; Lucidi, F. Promoting Media Literacy Online: An Intervention on Performance and Appearance Enhancement Substances with Sport High School Students. Public Health 2021, 18, 5596. [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, F.; Mallia, L.; Alivernini, F.; Chirico, A.; Manganelli, S.; Galli, F.; Biasi, V.; Zelli, A. The Effectiveness of a New School-Based Media Literacy Intervention on Adolescents’ Doping Attitudes and Supplements Use. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 256272. [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, Z.; Sibalis, A.; Sutherland, J.E. Are Media Literacy Interventions Effective at Changing Attitudes and Intentions towards Risky Health Behaviors in Adolescents? A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 140–152. [CrossRef]

- Tori, A.A.; Tori, R.; Nunes, F.D.L.D.S. Serious Game Design in Health Education: A Systematic Review. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2022, 15, 827–846. [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.; Chaldogeridis, A.; Politopoulos, N.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsiatsos, T. Users’ and Experts’ Evaluation of TARGET: A Serious Game for Mitigating Performance Enhancement Culture in Youth. In Internet of Things, Infrastructures and Mobile Applications; Auer, M.E., Tsiatsos, T., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; Vol. 1192 ISBN 978-3-030-49931-0.

- Brigham, T.J. An Introduction to Gamification: Adding Game Elements for Engagement. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2015, 34, 471–480. [CrossRef]

- Corti, K. Games-Based Learning: A Serious Business Application. Inf. PixelLearning 2006, 34(6), 1–20.

- Barikoukis, V.; Tsiatsos, T.; Politopoulos, N.; Stylianidis, P.; Ziagkas, E.; Loukovitis, A.; Lambros, L.; Antonia, Y. A Serious Game Approach in Mitigating Performance Enhancement Culture in Youth (GAME Project). Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2020, 916, 733–742. [CrossRef]

- Mallia, L.; Lucidi, F.; Zelli, A.; Violani, C. Doping Attitudes and the Use of Legal and Illegal Performance-Enhancing Substances Among Italian Adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2013, 22, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, M.R., Bakken, A., Loland, S. Anabolic–Androgenic Steroid Use and Correlates in Norwegian Adolescents. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 16, 903–910. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities. Recent Dev. Criminol. Theory Towar. Discip. Divers. Theor. Integr. 1999, 3, 193–209. [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Ring, C. Moral Identity Predicts Doping Likelihood via Moral Disengagement and Anticipated Guilt. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 293–301. [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, F., Zelli, A., Mallia, L., Grano, C., Russo, P. M., and Violani, C. The Social Cognitive Mechanisms Regulating Adolescents’ Use of Doping Substances. J. Sport. Sci. 2008, 26, 447–456. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford publications, 2017; ISBN 1462534651.

- Nicholls, A.R.; Morley, D.; Thompson, M.A.; Huang, C.; Abt, G.; Rothwell, M.; Cope, E.; Ntoumanis, N. The Effects of the IPlayClean Education Programme on Doping Attitudes and Susceptibility to Use Banned Substances among High-Level Adolescent Athletes from the UK: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 82, 102820. [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Barkoukis, V.; Hurst, P.; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.; Skoufa, L.; Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Ring, C. A Psychological Intervention Reduces Doping Likelihood in British and Greek Athletes: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 61, 102099. [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. Toward an Integrative Model of Doping Use: An Empirical Study with Adolescent Athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 37–50. [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Barkoukis, V.; Gucciardi, D.F.; Chan, D.K.C. Intentions and Doping Use : A Prospective Study. J. Sport Exerc. Pshycology 2017, 188–198.

- Kavussanu, M.; Hurst, P.; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.; Galanis, E.; King, A.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Ring, C. A Moral Intervention Reduces Doping Likelihood in British and Greek Athletes: Evidence from a Cluster Randomized Control Trial. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 43, 125–139. [CrossRef]

- Vasileios, B.; Thrasyvoulos, T.; Nikolaos, P.; Panagiotis, S.; Efthymios, Z.; Lamboros, L.; Antonia, Y. A Serious Game Approach in Anti-Doping Education : The Game Project The 15 Th International Scientific Conference ELearning and Software for Education Bucharest , April 11-12 , 2019. 15th Int. Sci. Conf. eLearning Softw. Educ. 2019, 451–455.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).