Submitted:

25 September 2023

Posted:

27 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

2.2. mRNA gene-expression analysis

2.3. Data analyses

3. Results

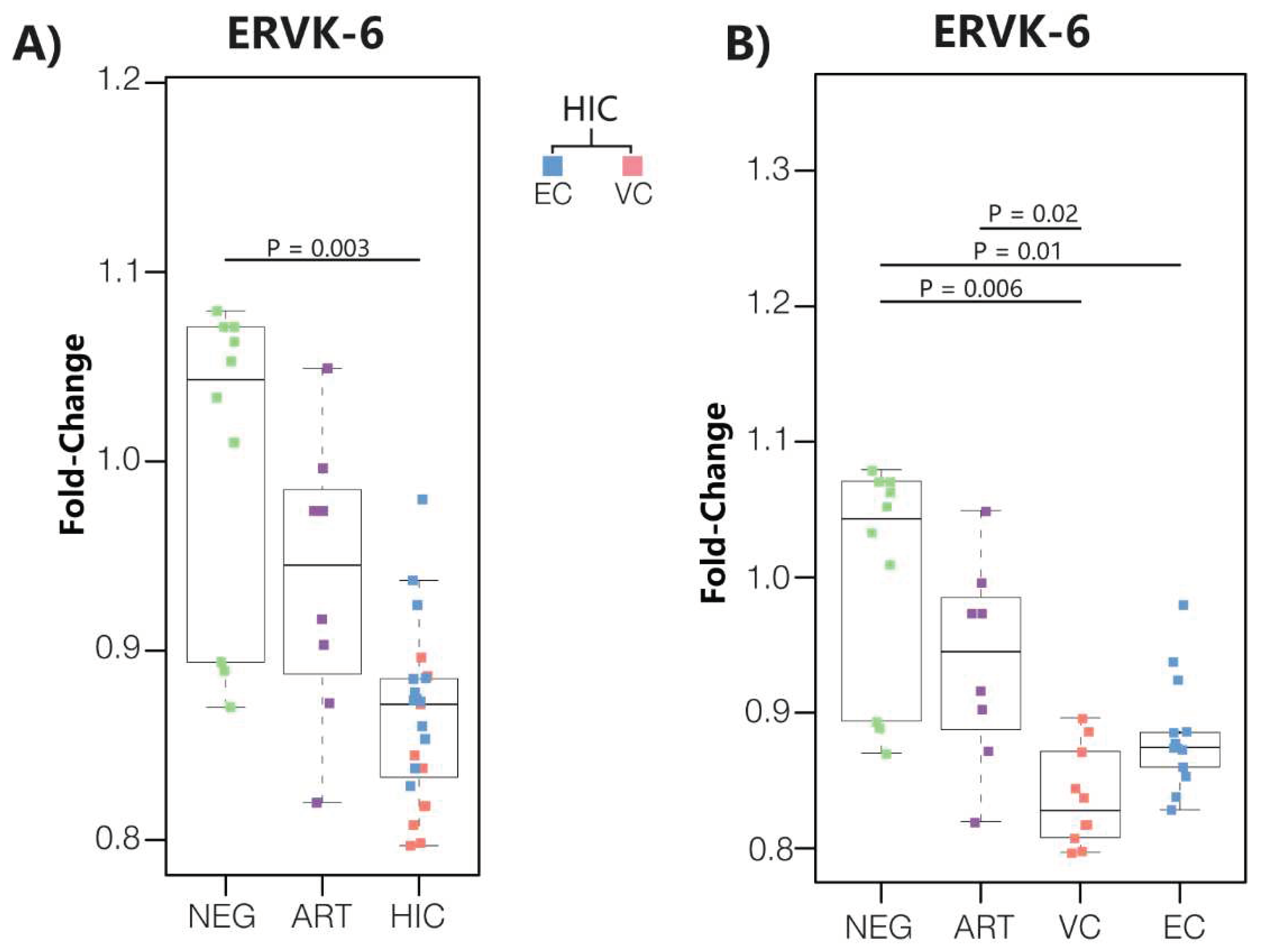

3.1. ERVK-6 mRNA levels are downregulated in HICs

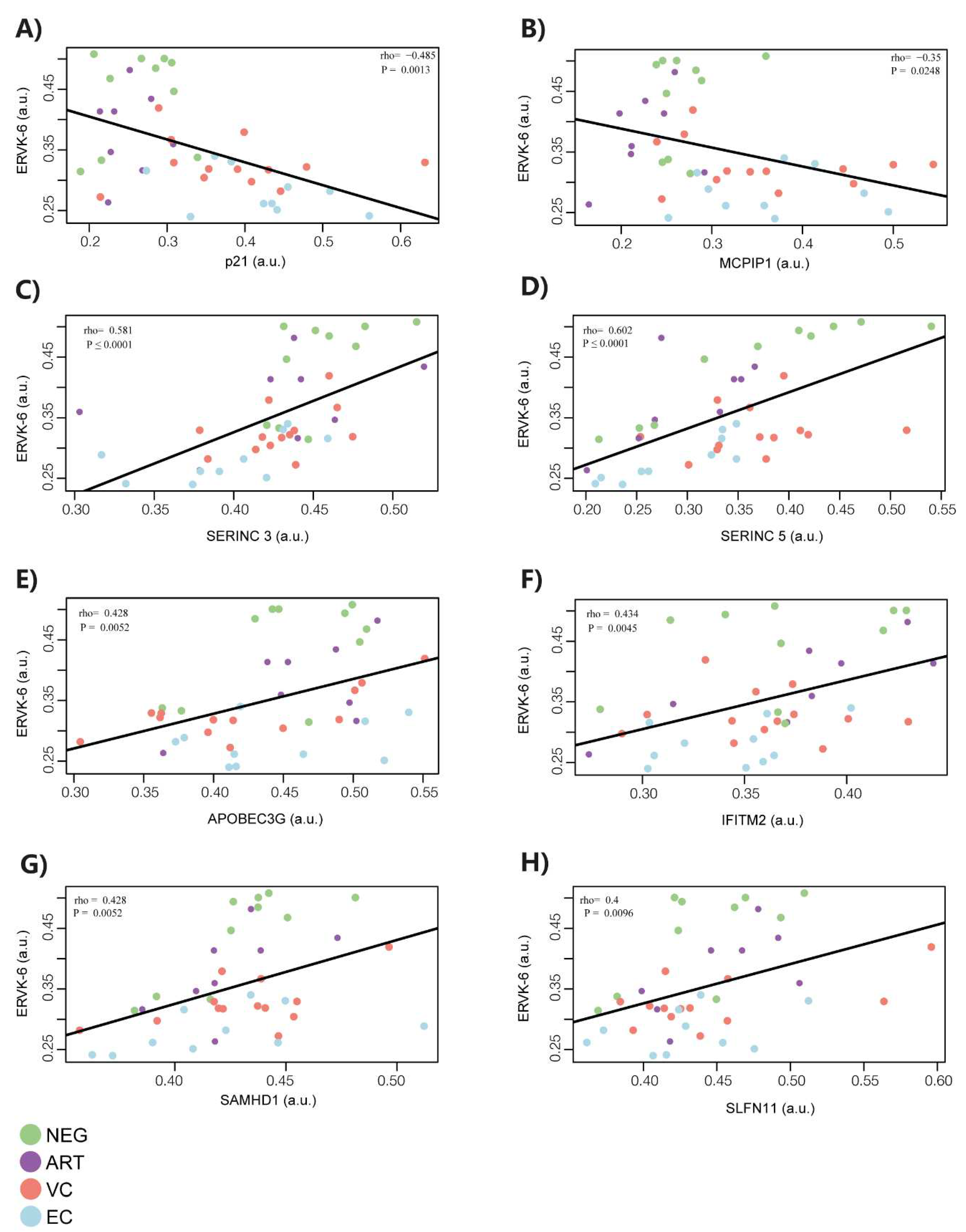

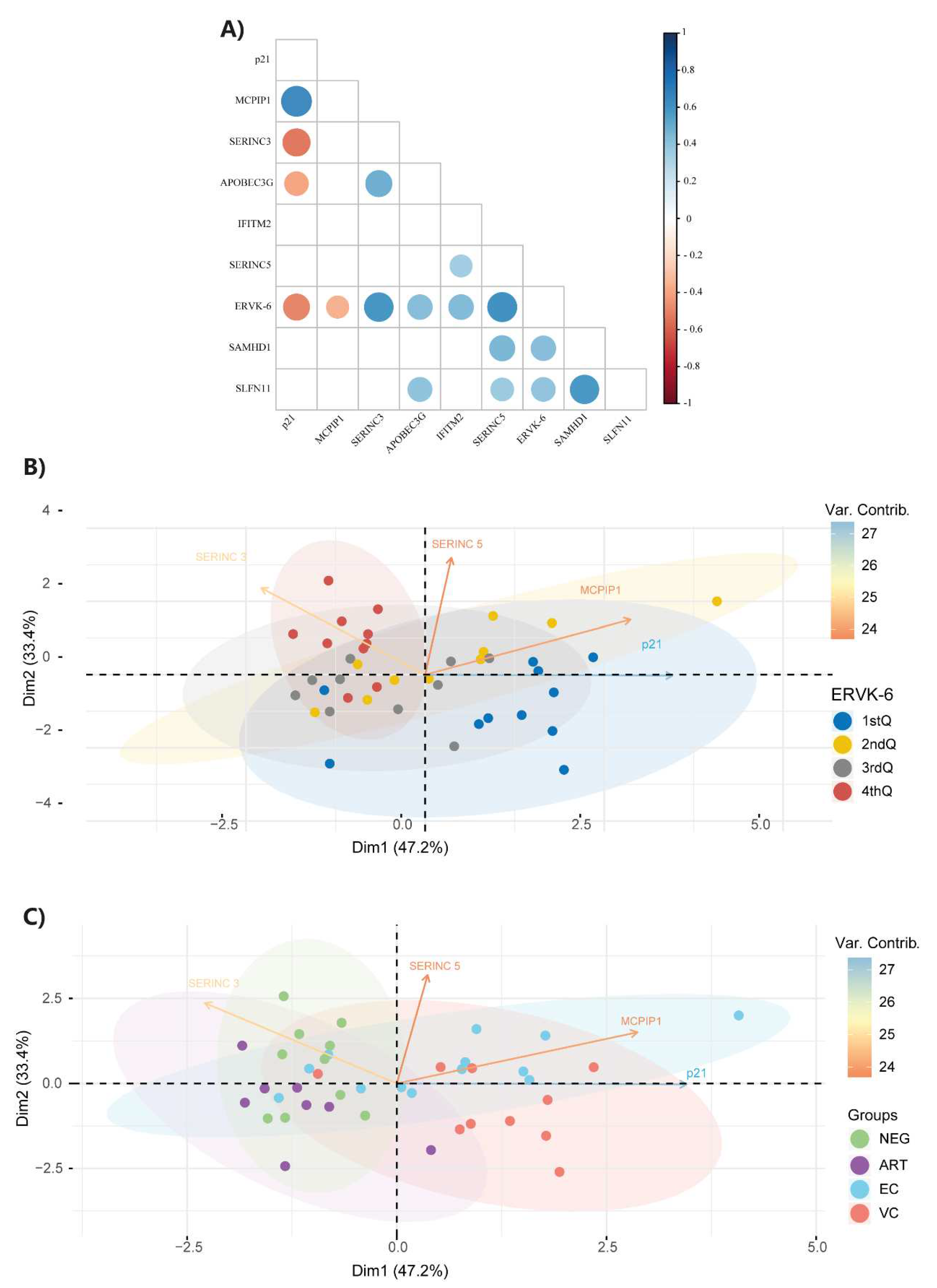

3.2. ERVK-6 mRNA and cellular restriction factor levels are correlated

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jern, P.; Coffin, J.M. Effects of Retroviruses on Host Genome Function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 709–732. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091501. [CrossRef]

- Agoni, L.; Guha, C.; Lenz, J. Detection of Human Endogenous Retrovirus K (HERV-K) Transcripts in Human Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2013.00180. [CrossRef]

- Cegolon, L.; Salata, C.; Weiderpass, E.; Vineis, P.; Palù, G.; Mastrangelo, G. Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Cancer Prevention: Evidence and Prospects. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-4. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Maldarelli, F.; Mellors, J.; Coffin, J.M. HIV-1 Infection Leads to Increased Transcription of Human Endogenous Retrovirus HERV-K (HML-2) Proviruses In Vivo but Not to Increased Virion Production. J Virol 2014, 88, 11108–11120. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01623-14. [CrossRef]

- Argaw-Denboba, A.; Balestrieri, E.; Serafino, A.; Cipriani, C.; Bucci, I.; Sorrentino, R.; Sciamanna, I.; Gambacurta, A.; Sinibaldi-Vallebona, P.; Matteucci, C. HERV-K Activation Is Strictly Required to Sustain CD133+ Melanoma Cells with Stemness Features. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2017, 36, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-016-0485-x. [CrossRef]

- Douville, R.; Liu, J.; Rothstein, J.; Nath, A. Identification of Active Loci of a Human Endogenous Retrovirus in Neurons of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011, 69, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22149. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lee, M.-H.; Henderson, L.; Tyagi, R.; Bachani, M.; Steiner, J.; Campanac, E.; Hoffman, D.A.; Von Geldern, G.; Johnson, K.; et al. Human Endogenous Retrovirus-K Contributes to Motor Neuron Disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aac8201. [CrossRef]

- Balada, E.; Vilardell-Tarrés, M.; Ordi-Ros, J. Implication of Human Endogenous Retroviruses in the Development of Autoimmune Diseases. International Reviews of Immunology 2010, 29, 351–370. https://doi.org/10.3109/08830185.2010.485333. [CrossRef]

- Temerozo, J.R.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Hottz, E.D.; Sacramento, C.Q.; De Paula Dias Da Silva, A.; Mandacaru, S.C.; Dos Santos Moraes, E.C.; Trugilho, M.R.O.; Gesto, J.S.M.; et al. Human Endogenous Retrovirus K in the Respiratory Tract Is Associated with COVID-19 Physiopathology. Microbiome 2022, 10, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01260-9. [CrossRef]

- Costas, J. Evolutionary Dynamics of the Human Endogenous Retrovirus Family HERV-K Inferred from Full-Length Proviral Genomes. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2001, 53, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002390010213. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.P.; Wildschutte, J.H.; Russo, C.; Coffin, J.M. Identification, Characterization, and Comparative Genomic Distribution of the HERV-K (HML-2) Group of Human Endogenous Retroviruses. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-8-90. [CrossRef]

- Young, G.R.; Terry, S.N.; Manganaro, L.; Cuesta-Dominguez, A.; Deikus, G.; Bernal-Rubio, D.; Campisi, L.; Fernandez-Sesma, A.; Sebra, R.; Simon, V.; et al. HIV-1 Infection of Primary CD4 + T Cells Regulates the Expression of Specific Human Endogenous Retrovirus HERV-K (HML-2) Elements. J Virol 2018, 92, e01507-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01507-17. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Galindo, R.; López, P.; Vélez, R.; Yamamura, Y. HIV-1 Infection Increases the Expression of Human Endogenous Retroviruses Type K (HERV-K) in Vitro. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2007, 23, 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2006.0117. [CrossRef]

- Vincendeau, M.; Göttesdorfer, I.; Schreml, J.M.H.; Wetie, A.G.N.; Mayer, J.; Greenwood, A.D.; Helfer, M.; Kramer, S.; Seifarth, W.; Hadian, K.; et al. Modulation of Human Endogenous Retrovirus (HERV) Transcription during Persistent and de Novo HIV-1 Infection. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-015-0156-6. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.B.; Garrison, K.E.; Mujib, S.; Mihajlovic, V.; Aidarus, N.; Hunter, D.V.; Martin, E.; John, V.M.; Zhan, W.; Faruk, N.F.; et al. HERV-K–Specific T Cells Eliminate Diverse HIV-1/2 and SIV Primary Isolates. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 4473–4489. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI64560. [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, C.E.; SenGupta, D.; Tandon, R.; Deeks, S.G.; Martin, J.N.; Jones, R.B.; Ostrowski, M.A.; Garrison, K.E.; Vázquez-Pérez, J.A.; Reyes-Terán, G.; et al. Human Endogenous Retrovirus Expression Is Inversely Associated with Chronic Immune Activation in HIV-1 Infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041021. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Galindo, R.; Kaplan, M.H.; Markovitz, D.M.; Lorenzo, E.; Yamamura, Y. Detection of HERV-K(HML-2) Viral RNA in Plasma of HIV Type 1-Infected Individuals. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2006, 22, 979–984. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2006.22.979. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Galindo, R.; Almodóvar-Camacho, S.; González-Ramírez, S.; Lorenzo, E.; Yamamura, Y. Short Communication: Comparative Longitudinal Studies of HERV-K and HIV-1 RNA Titers in HIV-1-Infected Patients Receiving Successful versus Unsuccessful Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2007, 23, 1083–1086. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2007.0054. [CrossRef]

- Garrison, K.E.; Jones, R.B.; Meiklejohn, D.A.; Anwar, N.; Ndhlovu, L.C.; Chapman, J.M.; Erickson, A.L.; Agrawal, A.; Spotts, G.; Hecht, F.M.; et al. T Cell Responses to Human Endogenous Retroviruses in HIV-1 Infection. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3, e165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030165. [CrossRef]

- De Mulder, M.; SenGupta, D.; Deeks, S.G.; Martin, J.N.; Pilcher, C.D.; Hecht, F.M.; Sacha, J.B.; Nixon, D.F.; Michaud, H.-A. Anti-HERV-K (HML-2) Capsid Antibody Responses in HIV Elite Controllers. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-017-0365-2. [CrossRef]

- SenGupta, D.; Tandon, R.; Vieira, R.G.S.; Ndhlovu, L.C.; Lown-Hecht, R.; Ormsby, C.E.; Loh, L.; Jones, R.B.; Garrison, K.E.; Martin, J.N.; et al. Strong Human Endogenous Retrovirus-Specific T Cell Responses Are Associated with Control of HIV-1 in Chronic Infection. J Virol 2011, 85, 6977–6985. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00179-11. [CrossRef]

- Michaud, H.-A.; De Mulder, M.; SenGupta, D.; Deeks, S.G.; Martin, J.N.; Pilcher, C.D.; Hecht, F.M.; Sacha, J.B.; Nixon, D.F. Trans-Activation, Post-Transcriptional Maturation, and Induction of Antibodies to HERV-K (HML-2) Envelope Transmembrane Protein in HIV-1 Infection. Retrovirology 2014, 11, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-11-10. [CrossRef]

- Russ, E.; Mikhalkevich, N.; Iordanskiy, S. Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Group K (HERV-K) HML-2 Correlates with Immune Activation of Macrophages and Type I Interferon Response. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e04438-22. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.04438-22. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; SenGupta, D.; Ndhlovu, L.C.; Vieira, R.G.S.; Jones, R.B.; York, V.A.; Vieira, V.A.; Sharp, E.R.; Wiznia, A.A.; Ostrowski, M.A.; et al. Identification of Human Endogenous Retrovirus-Specific T Cell Responses in Vertically HIV-1-Infected Subjects. J Virol 2011, 85, 11526–11531. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.05418-11. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez, M.J.; Swanson, M.D.; Contreras-Galindo, R.; Cookinham, S.; King, S.R.; Noel, R.J.; Kaplan, M.H.; Markovitz, D.M. Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Type K (HML-2) Is Activated by the Tat Protein of HIV-1. J Virol 2012, 86, 7790–7805. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.07215-11. [CrossRef]

- Hurst, T.; Magiorkinis, G. Epigenetic Control of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Expression: Focus on Regulation of Long-Terminal Repeats (LTRs). Viruses 2017, 9, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9060130. [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, S.S.D.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; Côrtes, F.H.; Delatorre, E.; Spangenberg, L.; Naya, H.; Seito, L.N.; Hoagland, B.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.G.; et al. Increased Expression of CDKN1A/P21 in HIV-1 Controllers Is Correlated with Upregulation of ZC3H12A/MCPIP1. Retrovirology 2020, 17, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-020-00522-4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Scadden, D.T.; Crumpacker, C.S. Primitive Hematopoietic Cells Resist HIV-1 Infection via p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI28971. [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, A.; David, A.; Le Rouzic, E.; Nisole, S.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Pancino, G. The CDK Inhibitor P21 Cip1/WAF1 Is Induced by FcγR Activation and Restricts the Replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 and Related Primate Lentiviruses in Human Macrophages. J Virol 2009, 83, 12253–12265. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01395-09. [CrossRef]

- Valle-Casuso, J.C.; Allouch, A.; David, A.; Lenzi, G.M.; Studdard, L.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Müller-Trutwin, M.; Kim, B.; Pancino, G.; Sáez-Cirión, A. P21 Restricts HIV-1 in Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells through the Reduction of Deoxynucleoside Triphosphate Biosynthesis and Regulation of SAMHD1 Antiviral Activity. J Virol 2017, 91, e01324-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01324-17. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Cung, T.; Seiss, K.; Beamon, J.; Carrington, M.F.; Porter, L.C.; Burke, P.S.; Yang, Y.; et al. CD4+ T Cells from Elite Controllers Resist HIV-1 Infection by Selective Upregulation of P21. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 1549–1560. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI44539. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Weiss, R.H.; Merani, S. Atorvastatin Restricts HIV Replication in CD4+ T Cells by Upregulation of P21. AIDS 2016, 30, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000917. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qiu, C.; Miao, R.; Zhou, J.; Lee, A.; Liu, B.; Lester, S.N.; Fu, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. MCPIP1 Restricts HIV Infection and Is Rapidly Degraded in Activated CD4+ T Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 19083–19088. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316208110. [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Blackshear, P.J. RNA-Binding Proteins in Immune Regulation: A Focus on CCCH Zinc Finger Proteins. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.129. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Feng, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, C.; Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.; Duan, M. MCPIP1 Attenuates the Innate Immune Response to Influenza A Virus by Suppressing RIG-I Expression in Lung Epithelial Cells. J Med Virol 2018, 90, 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24944. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, Q.; Xing, Y.; Chen, Z. MCPIP1 Negatively Regulate Cellular Antiviral Innate Immune Responses through DUB and Disruption of TRAF3-TBK1-IKKε Complex. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2018, 503, 830–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.083. [CrossRef]

- Lloberas, J.; Celada, A. P21 waf1/CIP1 , a CDK Inhibitor and a Negative Feedback System That Controls Macrophage Activation: HIGHLIGHTS. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 691–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200939262. [CrossRef]

- Scatizzi, J.C.; Mavers, M.; Hutcheson, J.; Young, B.; Shi, B.; Pope, R.M.; Ruderman, E.M.; Samways, D.S.K.; Corbett, J.A.; Egan, T.M.; et al. The CDK Domain of P21 Is a Suppressor of IL-1β-Mediated Inflammation in Activated Macrophages: Innate Immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 820–825. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200838683. [CrossRef]

- Trakala, M.; Arias, C.F.; García, M.I.; Moreno-Ortiz, M.C.; Tsilingiri, K.; Fernández, P.J.; Mellado, M.; Díaz-Meco, M.T.; Moscat, J.; Serrano, M.; et al. Regulation of Macrophage Activation and Septic Shock Susceptibility via P21(WAF1/CIP1): Innate Immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200838676. [CrossRef]

- Côrtes, F.H.; De Paula, H.H.S.; Bello, G.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; De Azevedo, S.S.D.; Caetano, D.G.; Teixeira, S.L.M.; Hoagland, B.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.G.; et al. Plasmatic Levels of IL-18, IP-10, and Activated CD8+ T Cells Are Potential Biomarkers to Identify HIV-1 Elite Controllers With a True Functional Cure Profile. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01576. [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, S.S.D.; Caetano, D.G.; Côrtes, F.H.; Teixeira, S.L.M.; Dos Santos Silva, K.; Hoagland, B.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.G.; Morgado, M.G.; Bello, G. Highly Divergent Patterns of Genetic Diversity and Evolution in Proviral Quasispecies from HIV Controllers. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-017-0354-5. [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Data by Geometric Averaging of Multiple Internal Control Genes. Genome Biol 2002, 3, research0034.1. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [CrossRef]

- Basso, D.; Pesarin, F.; Salmaso, L.; Solari, A. Nonparametric One-Way ANOVA. In Permutation Tests for Stochastic Ordering and ANOVA; Lecture Notes in Statistics; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009; Vol. 194, pp. 105–132 ISBN 978-0-387-85955-2.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2021.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR : An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Soft. 2008, 25. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01. [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. and Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7.; 2020.

- Allouch, A.; David, A.; Amie, S.M.; Lahouassa, H.; Chartier, L.; Margottin-Goguet, F.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Kim, B.; Sáez-Cirión, A.; Pancino, G. P21-Mediated RNR2 Repression Restricts HIV-1 Replication in Macrophages by Inhibiting dNTP Biosynthesis Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1306719110. [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.-J.; Chien, H.-L.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, B.-L.; Yu, H.-P.; Tang, W.-C.; Lin, Y.-L. MCPIP1 Ribonuclease Exhibits Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Effects through Viral RNA Binding and Degradation. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, 3314–3326. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt019. [CrossRef]

- Jura, J.; Skalniak, L.; Koj, A. Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1-Induced Protein-1 (MCPIP1) Is a Novel Multifunctional Modulator of Inflammatory Reactions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2012, 1823, 1905–1913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.06.029. [CrossRef]

- Uehata, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Vandenbon, A.; Matsushita, K.; Hernandez-Cuellar, E.; Kuniyoshi, K.; Satoh, T.; Mino, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Standley, D.M.; et al. Malt1-Induced Cleavage of Regnase-1 in CD4+ Helper T Cells Regulates Immune Activation. Cell 2013, 153, 1036–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.034. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Greene, W.C. Dynamic Roles for NF-κB in HTLV-I and HIV-1 Retroviral Pathogenesis: Pathogenic Human Retroviruses Subvert NF-κB. Immunological Reviews 2012, 246, 286–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01094.x. [CrossRef]

- Manghera, M.; Douville, R.N. Endogenous Retrovirus-K Promoter: A Landing Strip for Inflammatory Transcription Factors? Retrovirology 2013, 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-10-16. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Chande, A.; Ziglio, S.; De Sanctis, V.; Bertorelli, R.; Goh, S.L.; McCauley, S.M.; Nowosielska, A.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Luban, J.; et al. HIV-1 Nef Promotes Infection by Excluding SERINC5 from Virion Incorporation. Nature 2015, 526, 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15399. [CrossRef]

- Usami, Y.; Wu, Y.; Göttlinger, H.G. SERINC3 and SERINC5 Restrict HIV-1 Infectivity and Are Counteracted by Nef. Nature 2015, 526, 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15400. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Waheed, A.A.; Li, T.; Yu, J.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Yount, J.S.; Wen, H.; Freed, E.O.; Liu, S.-L. SERINC Proteins Potentiate Antiviral Type I IFN Production and Proinflammatory Signaling Pathways. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabc7611. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.abc7611. [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Xodo, L.E. Endogenous Retroviruses (ERVs): Does RLR (RIG-I-Like Receptors)-MAVS Pathway Directly Control Senescence and Aging as a Consequence of ERV De-Repression? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 917998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.917998. [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Zheng, M.; Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Kuang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Ouyang, L.; Lu, S.; Zhao, M. Ultraviolet Light Induces HERV Expression to Activate RIG-I Signalling Pathway in Keratinocytes. Experimental Dermatology 2022, exd.14568. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.14568. [CrossRef]

- Mikhalkevich, N.; O’Carroll, I.P.; Tkavc, R.; Lund, K.; Sukumar, G.; Dalgard, C.L.; Johnson, K.R.; Li, W.; Wang, T.; Nath, A.; et al. Response of Human Macrophages to Gamma Radiation Is Mediated via Expression of Endogenous Retroviruses. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009305. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009305. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Ren, J.; Fan, Y.; Sun, L.; Cao, G.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ji, Q.; et al. Resurrection of Endogenous Retroviruses during Aging Reinforces Senescence. Cell 2023, 186, 287-304.e26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.017. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kao, E.; Gao, X.; Sandig, H.; Limmer, K.; Pavon-Eternod, M.; Jones, T.E.; Landry, S.; Pan, T.; Weitzman, M.D.; et al. Codon-Usage-Based Inhibition of HIV Protein Synthesis by Human Schlafen 11. Nature 2012, 491, 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11433. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yu, L.; Tong, W.; Gao, F.; Li, L.; Huang, Q.; et al. Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 Is a Key Regulation Factor for Inducing the Expression of SAMHD1 in Antiviral Innate Immunity. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29665. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29665. [CrossRef]

- Pauli, E.-K.; Schmolke, M.; Hofmann, H.; Ehrhardt, C.; Flory, E.; Münk, C.; Ludwig, S. High Level Expression of the Anti-Retroviral Protein APOBEC3G Is Induced by Influenza A Virus but Does Not Confer Antiviral Activity. Retrovirology 2009, 6, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-6-38. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.R.; Williams, T.M.; Siliciano, R.F.; Blankson, J.N. Maintenance of Viral Suppression in HIV-1–Infected HLA-B*57+ Elite Suppressors despite CTL Escape Mutations. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2006, 203, 1357–1369. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20052319. [CrossRef]

- Mens, H.; Kearney, M.; Wiegand, A.; Shao, W.; Schønning, K.; Gerstoft, J.; Obel, N.; Maldarelli, F.; Mellors, J.W.; Benfield, T.; et al. HIV-1 Continues To Replicate and Evolve in Patients with Natural Control of HIV Infection. J Virol 2010, 84, 12971–12981. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00387-10. [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.; Brennan, T.P.; O’Connell, K.A.; Bailey, J.R.; Ray, S.C.; Siliciano, R.F.; Blankson, J.N. Evolution of the HIV-1 Nefgene in HLA-B*57 Positive Elite Suppressors. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-7-94. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.A.; Brennan, T.P.; Bailey, J.R.; Ray, S.C.; Siliciano, R.F.; Blankson, J.N. Control of HIV-1 in Elite Suppressors despite Ongoing Replication and Evolution in Plasma Virus. J Virol 2010, 84, 7018–7028. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00548-10. [CrossRef]

- Pernas, M.; Tarancón-Diez, L.; Rodríguez-Gallego, E.; Gómez, J.; Prado, J.G.; Casado, C.; Dominguez-Molina, B.; Olivares, I.; Coiras, M.; León, A.; et al. Factors Leading to the Loss of Natural Elite Control of HIV-1 Infection. J Virol 2018, 92, e01805-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01805-17. [CrossRef]

- Boritz, E.A.; Darko, S.; Swaszek, L.; Wolf, G.; Wells, D.; Wu, X.; Henry, A.R.; Laboune, F.; Hu, J.; Ambrozak, D.; et al. Multiple Origins of Virus Persistence during Natural Control of HIV Infection. Cell 2016, 166, 1004–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.039. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.; Goujon, C.; Malim, M.H. HIV-1 and Interferons: Who’s Interfering with Whom? Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3449. [CrossRef]

- Utay, N.S.; Douek, D.C. Interferons and HIV Infection: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. PAI 2016, 1, 107. https://doi.org/10.20411/pai.v1i1.125. [CrossRef]

- Russ, E.; Iordanskiy, S. Endogenous Retroviruses as Modulators of Innate Immunity. Pathogens 2023, 12, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12020162. [CrossRef]

- Côrtes, F.H.; Passaes, C.P.B.; Bello, G.; Teixeira, S.L.M.; Vorsatz, C.; Babic, D.; Sharkey, M.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.; Stevenson, M.; et al. HIV Controllers With Different Viral Load Cutoff Levels Have Distinct Virologic and Immunologic Profiles. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2015, 68, 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000500. [CrossRef]

- Caetano, D.G.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; Hottz, E.D.; Vilela, L.M.; Cardoso, S.W.; Hoagland, B.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.G.; Morgado, M.G.; Bozza, P.T.; et al. Increased Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Risk in HIV-1 Viremic Controllers and Low Persistent Inflammation in Elite Controllers and Art-Suppressed Individuals. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6569. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10330-9. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.W.; Brenchley, J.; Sinclair, E.; McCune, J.M.; Roland, M.; Page-Shafer, K.; Hsue, P.; Emu, B.; Krone, M.; Lampiris, H.; et al. Relationship between T Cell Activation and CD4 + T Cell Count in HIV-Seropositive Individuals with Undetectable Plasma HIV RNA Levels in the Absence of Therapy. J INFECT DIS 2008, 197, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1086/524143. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Wilson, E.M.P.; Sheikh, V.; Rupert, A.; Mendoza, D.; Yang, J.; Lempicki, R.; Migueles, S.A.; Sereti, I. Evidence for Innate Immune System Activation in HIV Type 1–Infected Elite Controllers. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 209, 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit581. [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, F.; Lo, J.; Triant, V.A.; Wei, J.; Buzon, M.J.; Fitch, K.V.; Hwang, J.; Campbell, J.H.; Burdo, T.H.; Williams, K.C.; et al. Increased Coronary Atherosclerosis and Immune Activation in HIV-1 Elite Controllers. AIDS 2012, 26, 2409–2412. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835a9950. [CrossRef]

- Noel, N.; Boufassa, F.; Lécuroux, C.; Saez-Cirion, A.; Bourgeois, C.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Goujard, C.; Rouzioux, C.; Meyer, L.; Pancino, G.; et al. Elevated IP10 Levels Are Associated with Immune Activation and Low CD4+ T-Cell Counts in HIV Controller Patients. AIDS 2014, 28, 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000174. [CrossRef]

- Platten, M.; Jung, N.; Trapp, S.; Flossdorf, P.; Meyer-Olson, D.; Schulze Zur Wiesch, J.; Stephan, C.; Mauss, S.; Weiss, V.; Von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; et al. Cytokine and Chemokine Signature in Elite Versus Viremic Controllers Infected with HIV. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2016, 32, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2015.0226. [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, J.; Jacobs, Jr, D.R.; Baker, J.V.; Calmy, A.; Duprez, D.; La Rosa, A.; Kuller, L.H.; Pett, S.L.; Ristola, M.; Ross, M.J.; et al. Markers of Inflammation, Coagulation, and Renal Function Are Elevated in Adults with HIV Infection. J INFECT DIS 2010, 201, 1788–1795. https://doi.org/10.1086/652749. [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G. HIV Infection, Inflammation, Immunosenescence, and Aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [CrossRef]

- Hocini, H.; Bonnabau, H.; Lacabaratz, C.; Lefebvre, C.; Tisserand, P.; Foucat, E.; Lelièvre, J.-D.; Lambotte, O.; Saez–Cirion, A.; Versmisse, P.; et al. HIV Controllers Have Low Inflammation Associated with a Strong HIV-Specific Immune Response in Blood. J Virol 2019, 93, e01690-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01690-18. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).