1. Introduction

Normal human physiology has an absolute requirement for essential micronutrients (vitamins and trace elements) for adequate functioning of enzymes that rely on these micronutrients for their various activities. Vitamin C is one such essential micronutrient which is required through our diet, primarily from fresh fruits and vegetables [

1], due to genetic mutations resulting in loss of our ability to synthesise the nutrient in our livers [

2]. Although best known for its antioxidant activities, being able to scavenge a wide range reactive oxygen species [

3], the vitamin has pleiotropic functions in human physiology through acting as a cofactor for a family of metalloenzymes with numerous biosynthetic and regulatory functions [

4,

5,

6]. As such, there has been significant interest in the role of vitamin C in both the prevention and treatment of various conditions, particularly those potentially modifiable by lifestyle and dietary changes, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [

7,

8,

9,

10].

T2DM is a chronic health condition characterised by severe metabolic dysregulation and elevated morbidity and mortality [

11,

12]. Compared to healthy controls, vitamin C status is lower in people with T2DM, and the status of those with prediabetes and T1DM tends to be intermediate between that of healthy controls and those with T2DM [

13,

14]. There are several factors that could account for this observation in people with T2DM. Lower dietary intake of the vitamin may be anticipated, through avoidance of high sugar content fruit for example, however, there is generally a trend towards improved dietary intake of the vitamin following a diagnosis of T2DM [

15,

16], thus lower dietary intake does not appear to account for the lower vitamin C status observed [

13,

17]. Instead, likely factors include enhanced oxidative stress related to abdominal fat-related inflammation [

18], and a generally higher body weight resulting in a volumetric dilution of the vitamin [

19]. Furthermore, enhanced renal leak of the vitamin is more prevalent in people with T2DM and may be related to diabetic kidney dysfunction [

20,

21].

What is yet to be determined is how much extra vitamin C people with diabetes need to consume to compensate for the enhanced metabolic turnover, volumetric dilution and urinary loss of the vitamin. Recently, analysis of vitamin C dose-concentration relationships has allowed for the estimation of vitamin C requirements based on various demographic and lifestyle factors, such smoking and body weight [

22]. Therefore, in the current study we analysed data from two large international cohorts, the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017/2018 and the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC)-Norfolk study, to assess vitamin C dose-concentration relationships in people with diabetes to estimate how much extra vitamin C is required to reach an equivalent adequate circulating status (≥50 µmol/L) to those without diabetes. Due to close associations of body weight and BMI with the inflammatory biomarker and cardiovascular disease risk factor C-reactive protein (CRP), the impact of CRP as a surrogate biomarker for vitamin C requirements was also explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NHANES 2017-2018 Cohort

NHANES uses a complex, multistage, probability sampling design to capture a representative sample of the US non-institutionalized civilian population. NHANES 2017/2018 data was extracted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics site:

www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm, as described previously [

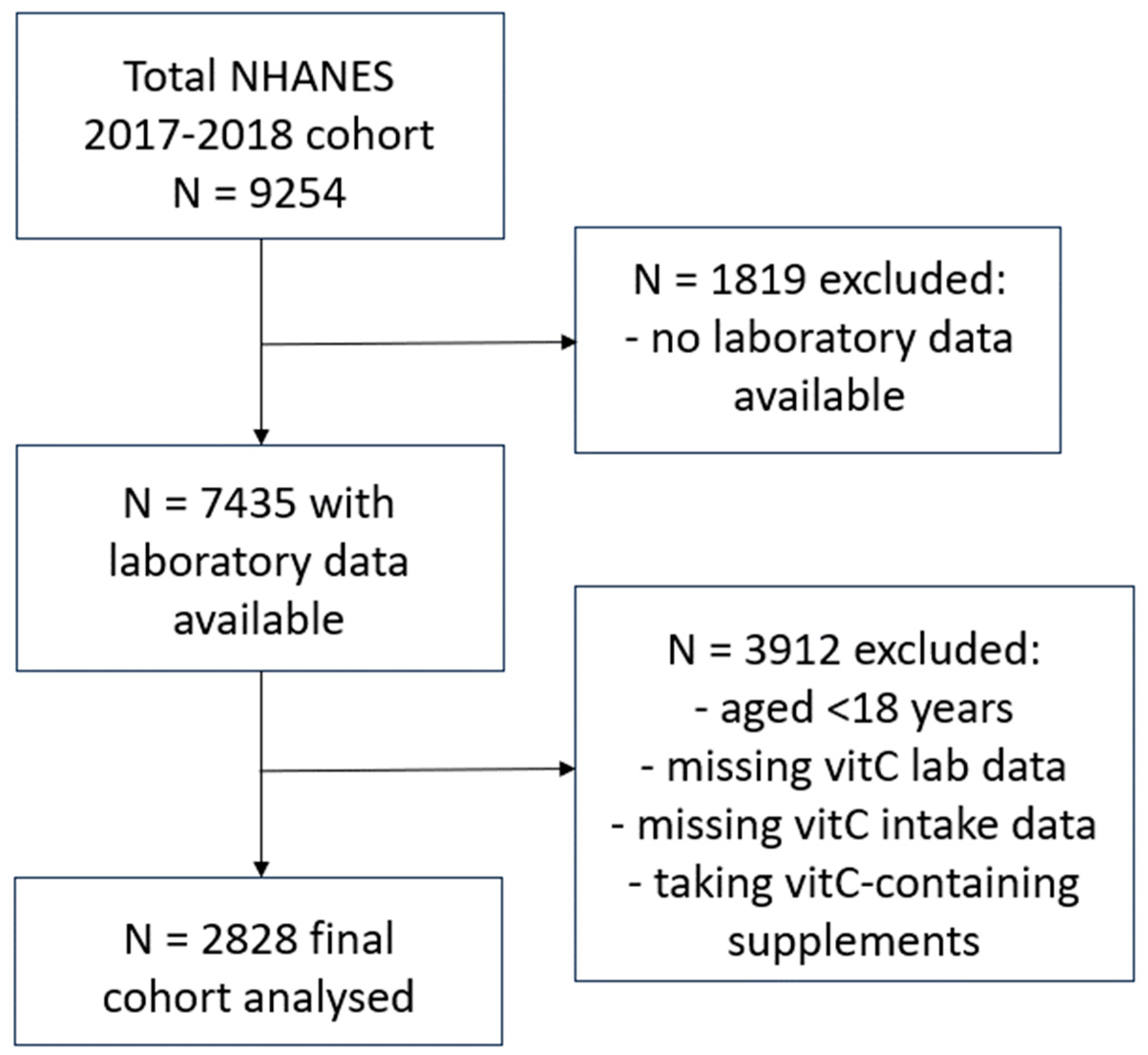

22]. Briefly, the final cohort (n = 2828) comprised adults aged 18 years or older, who had vitamin C laboratory values available, had completed two 24-hour dietary recalls and were not consuming vitamin C containing supplements (

Figure 1). Variables collected for the current study included: age, sex, ethnicity, poverty income ratio, smoking status (including number of years smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day), body weight and BMI, waist to hip ratio, blood pressure and vitamin C intake (derived from the mean of the two 24-hour dietary recalls). Laboratory variables included: non-fasting serum vitamin C concentrations (measured using isocratic ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection [

23]), C-reactive protein concentrations, glycaemic indices (e.g. HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, insulin), lipid markers (e.g. triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol) and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR).

2.2. Assessment of Diabetes

The diabetes-related information comprised personal interview data on diabetes and use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications. The diabetes-related questions were asked, in the home, by trained interviewers using a Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) system. Those with self-reported diabetes at baseline answered “yes” to the following question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” People with undiagnosed diabetes were identified using HbA1c concentrations ≥6.5%. The group with self-reported diabetes was further stratified into those with T2DM vs T1DM using the treatment-based algorithm developed by Mosslemi et al [

24], which utilises the following questions: “Are you now taking insulin?”, “For how long have you been taking insulin?”, and “Are you now taking diabetic pills to lower your blood sugar?”, as well as the time since diagnosis to distinguish between T1DM and T2DM. People with prediabetes were identified using circulating HbA1c values between 5.7 and 6.4%.

2.3. EPIC-Norfolk Cohort

The EPIC-Norfolk study is a population-based prospective cohort study that recruited over 30,000 men and women aged 40-79 years at baseline between 1993 and 1997 from 35 participating general practices in Norfolk (

https://www.epic-norfolk.org.uk). Individuals provided information about lifestyle behaviours, including diet and physical activity, and attended a baseline health check including the provision of blood samples and the collection of anthropometric data. The final cohort (n = 20692) comprised participants who were not consuming vitamin C supplements; these had vitamin C laboratory values and complete 7-day food diary data available. Variables collected for the current study included: age, sex, smoking status (never, current, former), weight and BMI, vitamin C intake (derived from baseline 7-day food diaries [

25,

26]) and non-fasting plasma vitamin concentrations (analysed using a fluorometric assay [

27]). People with established diabetes at baseline were defined as those who responded “yes” to the diabetes option of the question: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following?” followed by a list of conditions including diabetes, heart attack, and stroke [

28].

2.4. Data Analyses

Median and interquartile range (Q1, Q3) were used for continuous variables and counts with percentages were used for categorical variables. Group differences were assessed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests with p values < 0.05 signifying statistical significance. Linear regressions were determined using Pearson coefficient and correlations using Spearman r. To estimate the vitamin C intakes required to reach ‘adequate’ serum vitamin C concentrations of 50 µmol/L and maximal steady-state serum concentrations attained at intakes of 200 mg/d, sigmoidal (four parameter logistic) curves with asymmetrical 95% confidence intervals were fitted to vitamin C dose-concentration data. To calculate intake differences and relative requirements, the upper 95% CI of the first curve was related to the lower 95% CI of the second curve. Data were missing for smoking status for n = 79 (2.8%) participants in the NHANES cohort and n = 162 (0.8%) in the EPIC cohort; these participants were excluded from subgroup analyses stratified by smoking status. Data analyses and graphical presentations were carried out using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the NHANES Cohort Relative to Diabetes Status

The total NHANES cohort comprised 2828 non-supplementing adults with a median (IQR) age of 48 (32, 62) years. The cohort was further stratified relative to diabetes status. Those who answered “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” (n = 393) or their HbA1c concentration was ≥6.5% if they had answered “no” to this question (n = 95), giving a total of 488 (17%) people with diabetes and 2340 (83%) without. Internationally, the prevalence of T2DM is much higher than that of T1DM and this difference is confirmed in the NHANES data. The group with self-reported diabetes (n = 393) was further stratified into those with T2DM vs T1DM using the treatment-based algorithm developed by Mosslemi et al [

24]. Only a small number were identified as T1DM (n = 17; 0.6% of the total cohort), whereas 370 were identified as T2DM (with n = 24 of these being possible T2DM). The current study has therefore combined data from those with T1DM and T2DM into a single category of diabetes. The median age of diabetes diagnosis was 50 (40, 58) years. The diabetes group was significantly older than the no diabetes cohort (62 [52, 69] years vs 43 [29, 60] years, respectively; p < 0.0001), and although fewer smoked in the diabetes group, those who smoked had been smoking for significantly longer (

Table 1). The participants in the diabetes group were also significantly heavier and had larger waist to hip ratio, and a higher systolic blood pressure than those in the no diabetes group (p < 0.0001).

Blood parameters also indicated significant differences between the diabetes and no diabetes groups (

Table 2). Participants with diabetes had significantly higher C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations, with the median value being in the high clinical risk category, i.e. >3 mg/L, as well as a higher percentage of HbA1c, and fasting blood glucose and fasting insulin concentrations (p < 0.0001). Significant differences were also observed with blood lipids (triglycerides and cholesterol) between the two groups (

Table 2), as well as a higher urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), with >30% of the participants in the diabetes group exhibiting microalbuminuria (i.e. ACR >30 mg/g).

3.2. Vitamin C Status and Intake Relative to Diabetes Status in the NHANES Cohort

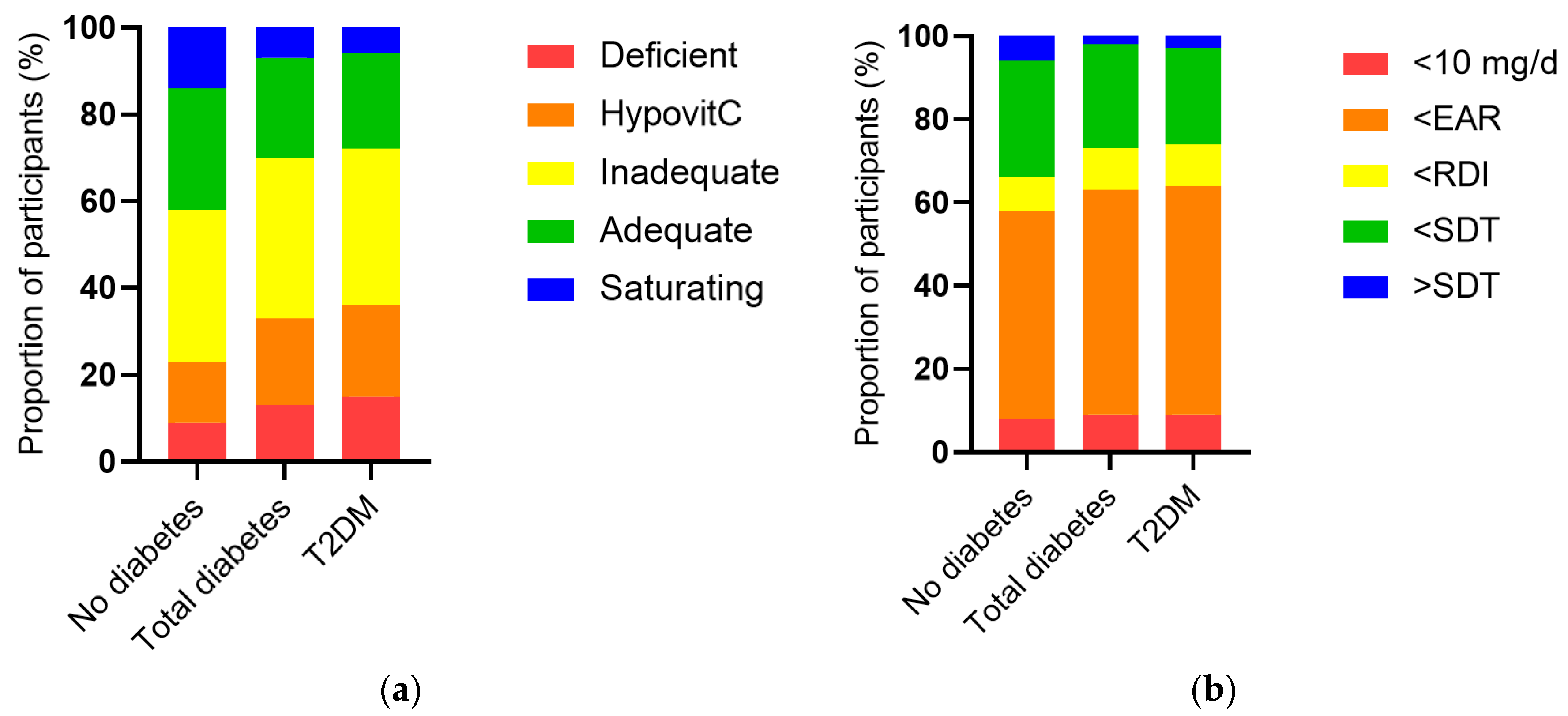

The vitamin C intake of the cohort was a median of 53 (24, 102) mg/d and was associated with a less than adequate median vitamin C status of 43 (23, 60) µmol/L. When the cohort was stratified by diabetes status, the group with diabetes had significantly lower vitamin C status than the group without diabetes (38 [17, 52] µmol/L vs 44 [25, 61] µmol/L, p < 0.0001), as well as a higher proportion of hypovitaminosis C and vitamin C deficiency (p < 0.0001,

Figure 2a). This was despite a comparable dietary intake to the group without diabetes (51 [26, 93] mg/d vs 53 [24, 104] mg/d, p = 0.5). The proportion of participants with an intake less than the estimated average requirement (EAR) was slightly higher in the group with diabetes (p = 0.04;

Figure 2b). Comparable results were observed for the T2DM subgroup (

Figure 2). Of note, there were significant inverse correlations between serum vitamin C and the blood biomarkers CRP (r = -0.190, p <0.0001), HbA1c (r = -0.093, p < 0.0001) and ACR (r = -0.077, p <0.0001), as well as other glycaemic and lipid markers (

Table 3).

3.3. Vitamin C requirements Stratified by Diabetes in the NHANES and EPIC-Norfolk Cohorts

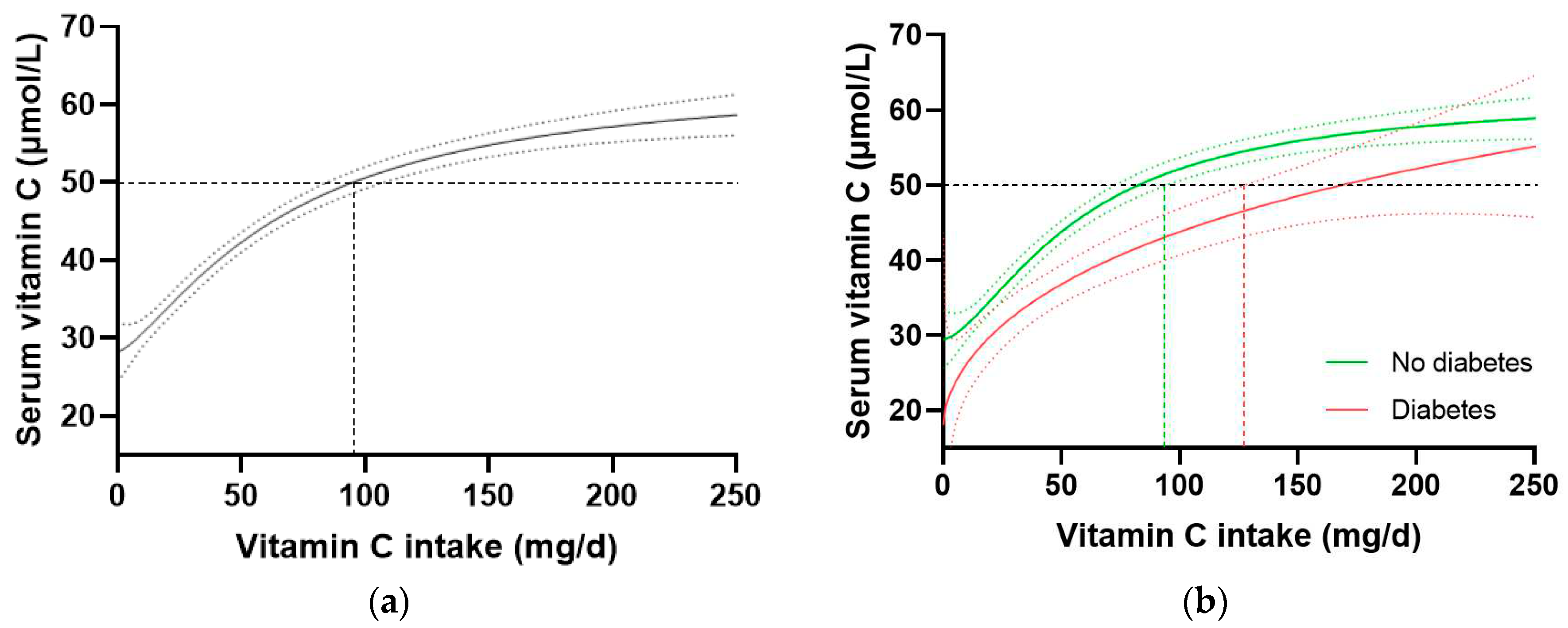

In the total NHANES cohort (n = 2828), the intake of vitamin C required to reach ‘adequate’ serum concentrations (i.e. 50 µmol/L) was 97 (85, 106) mg/d (

Figure 3a). When the cohort was stratified by diabetes status, the group without diabetes (n = 2340) reached 50 µmol/L at an intake of 81 (72, 93) mg/d, whilst the group with diabetes (n = 488) required an intake of 166 (126, NA) mg/d (

Figure 3b). Comparable results were observed when the T2DM subgroup was compared with the no diabetes cohort. No difference in vitamin C requirements was observed for those with prediabetes (80 [63, 100] mg/d, n = 707) relative to those without prediabetes (81 [69, 96] mg/d, n = 1629). Since smoking is known to negatively affect the vitamin C dose-concentration relationship, resulting in higher vitamin C requirements in smokers, the participants who were current smokers (n = 681) and those without smoking status information (n = 79) were excluded and the dose-concentration curves of non-smokers (n = 2069) were compared (

Table 4). Although the curves were shifted to the left (i.e. requiring lower intakes to reach 50 µmol/L serum vitamin C), the higher requirement for vitamin C to reach adequate serum concentrations was still evident in the non-smoking participants with diabetes (n = 378) relative to the non-smoking participants without diabetes (n = 1960;

Table 4). Overall, the participants with diabetes had a 1.4-fold higher requirement for vitamin C than those without diabetes, corresponding to an additional intake required to reach adequate vitamin C status being ~30 mg/d (the difference between the 95% CIs of the two curves).

To confirm these findings in another cohort, we interrogated the EPIC-Norfolk dataset. This cohort was significantly larger (n = 20692) than the NHANES cohort, but had a relatively lower proportion of participants with self-reported diabetes (n = 475, i.e. 2.3%). A number of other differences were apparent between the two cohorts. For example, the EPIC-Norfolk cohort was older (59 [51, 67] years), comprised a slightly higher proportion of females (53%), had a much lower prevalence of current smoking (11%), and a lower median weight (73 [64, 82] kg), BMI (26 [24, 28] kg/m

2), and waist to hip ratio (0.86 [0.78, 0.93]), as well as a higher median vitamin C intake (76 [51, 112) mg/d) and correspondingly higher vitamin C status (53 [40, 64] µmol/L) than the NHANES cohort (

Table 1; all p < 0.0001). Nevertheless, comparable trends in vitamin C requirements were observed in this cohort (

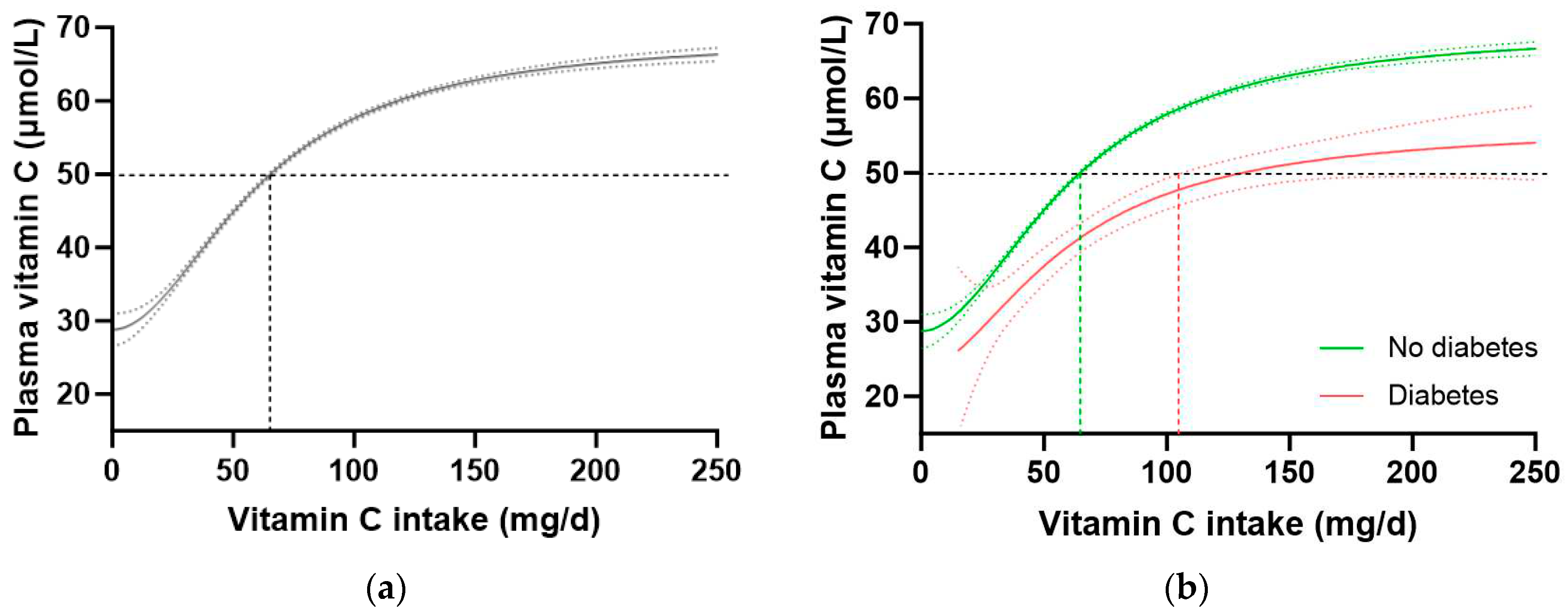

Table 4). The total cohort required a vitamin C intake of 65 (64, 66) mg/d to reach adequate serum status (

Figure 4a), and when stratified by diabetes status, the group without diabetes required an intake of 64 (63, 65) mg/d while the group with diabetes required 129 (104, NA) mg/d to reach equivalent status (

Figure 4b). This corresponded to a 1.6-fold higher requirement for vitamin C for people with diabetes, equating to an additional intake requirement of ~39 mg/d to reach adequate serum concentrations of 50 µmol/L (

Table 4). Furthermore, at a dietary intake of 200 mg/d, the people with diabetes did not reach as higher steady state concentration of vitamin C as those without (53 [49, 57] µmol/L vs 65 [66, 64] µmol/L, respectively). Similar values were observed in the non-smoking cohort (n = 18185) stratified by diabetes status (

Table 4).

3.4. CRP as a surrogate Biomarker for the Vitamin C Dose-Concentration Relationship

We have previously shown that body weight (and BMI) have a strong impact on both vitamin C concentrations and intake requirements in the NHANES cohort, with heavier BMI and weight tertiles having, respectively, 1.8- to 2-fold higher vitamin C requirement than the lighter BMI/weight tertiles [

22]. Therefore, we assessed the associations between body weight and BMI with CRP to determine if CRP could be used as a surrogate biomarker for vitamin C intake requirements. There was a strong correlation between body weight and CRP concentrations in the NHANES cohort (r = 0.408, p < 0.0001), corresponding to a 0.84 mg/L increase in CRP for every 10 kg in weight gain. Similarly, a strong correlation was found between BMI and CRP concentrations (r = 0.498, p < 0.0001), corresponding to a 0.78 mg/L increase in CRP for every 2.5 kg/m2 gain in BMI.

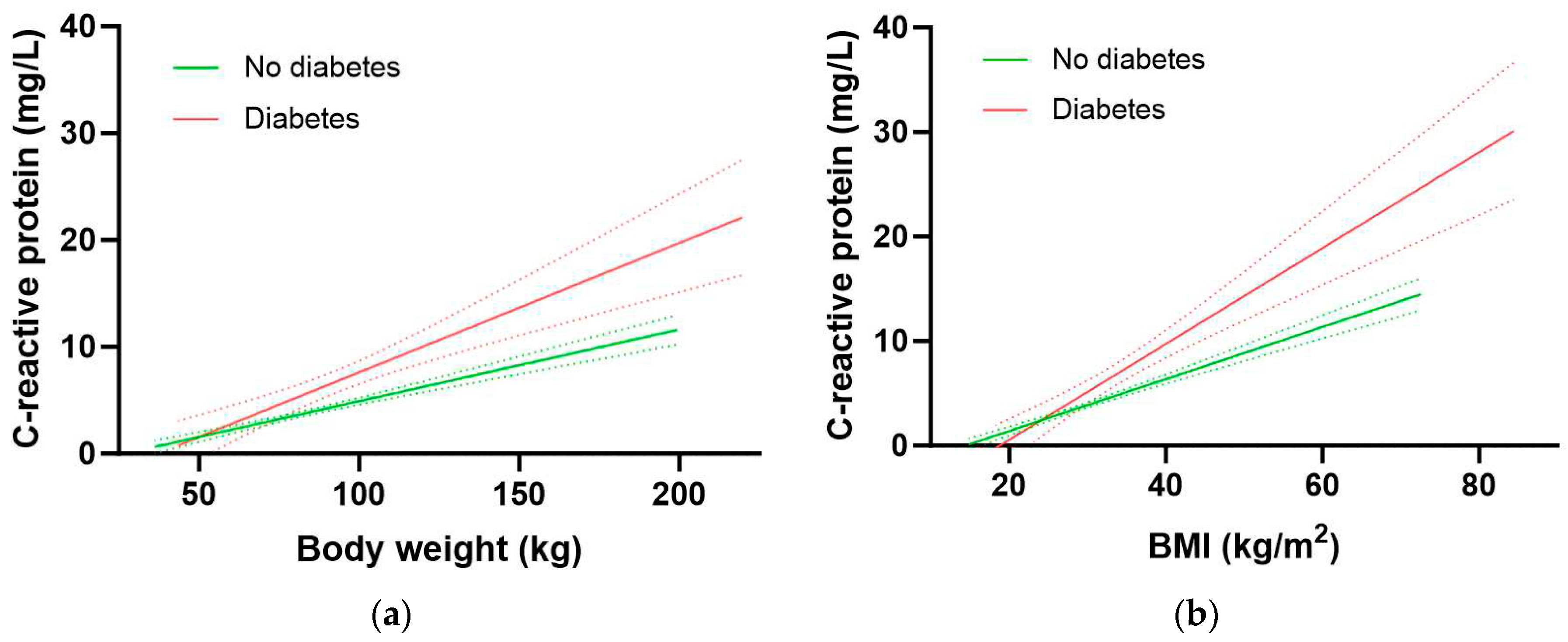

The participants with diabetes had significantly higher inflammation as assessed by CRP concentrations relative to participants without diabetes (3.2 [1.6, 7.1] mg/L vs 1.8 [0.9, 4.3] mg/L, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, the group with diabetes had a significantly higher 1.21 mg/L increase in CRP for every 10 kg in weight gain relative to the group without diabetes (0.67 mg/L CRP per 10 kg weight gain; p = 0.0005;

Figure 5a). Similarly, there was a 1.15 mg/L increase in CRP for every 2.5 kg/m2 gain in BMI in the group with diabetes relative to an increase of 0.63 mg/L CRP for every 2.5 kg/m2 gain in BMI in the group without diabetes (p <0.0001;

Figure 5b). Thus, people with diabetes have higher CRP concentrations at equivalent BMIs (and weights) to those without diabetes. This elevated inflammation could be related to greater central obesity as evidenced by a higher waist to hip ratio in people with diabetes (0.99 [0.94, 1.04]) relative to those without (0.93 [0.87, 0.98]; p > 0.0001).

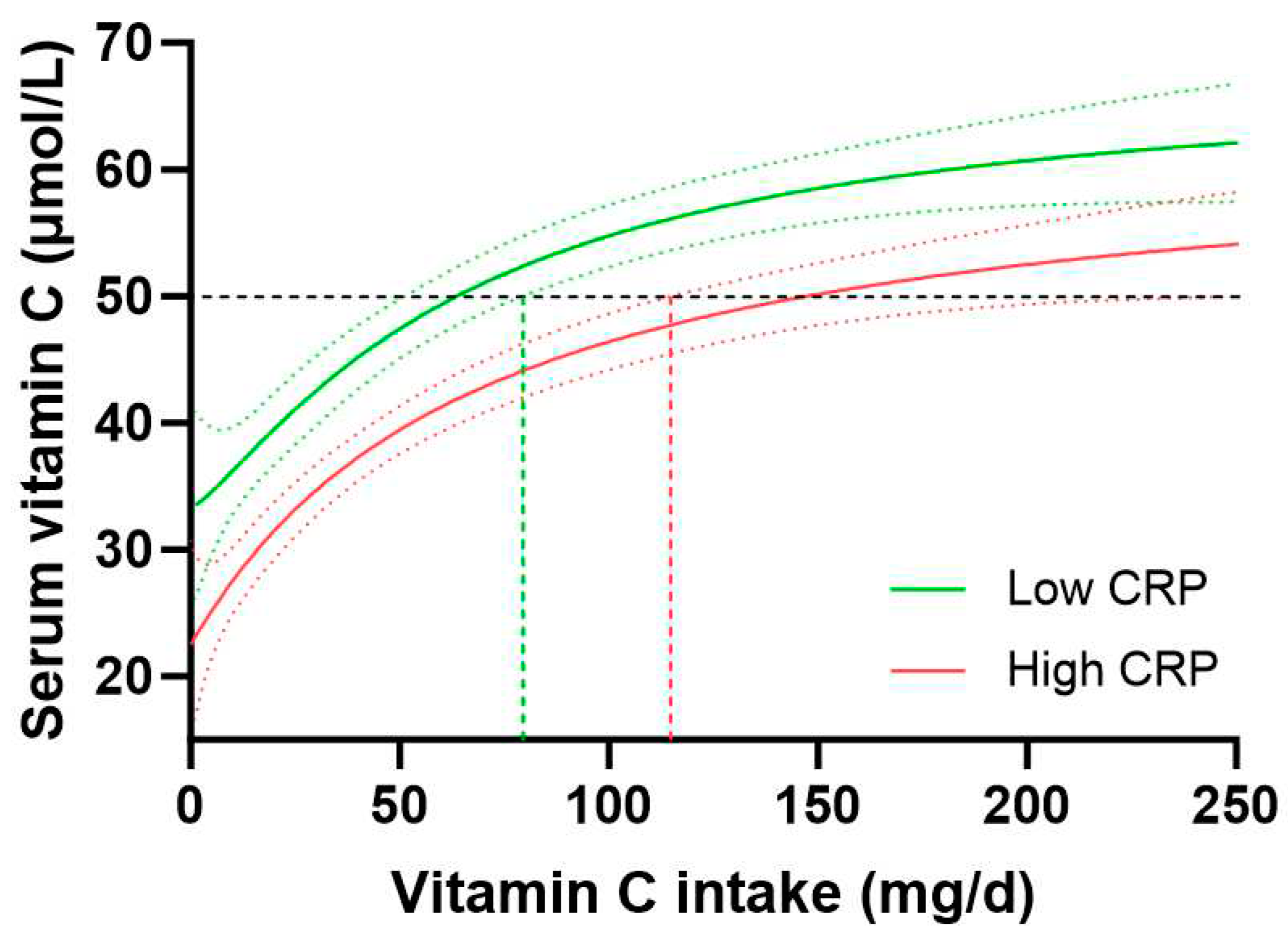

Assessment of the vitamin C dose-concentration relationship for those with low CRP (< 1 mg/L, n = 765) vs high CRP (>3 mg/L, n = 1081) indicated a vitamin C intake of 63 (51, 79) mg/d for people with low CRP to reach 50 µmol/L vitamin C concentrations relative to 146 (114, 229) mg/d for those with high CRP to reach equivalent plasma concentrations of the vitamin (

Figure 6). People with medium CRP concentrations (1-3 mg/L) required vitamin C intakes of 91 (78, 113) mg/d to reach adequate circulating status. Overall, this equated to a 1.4-fold higher vitamin C requirement for people with high CRP vs low CRP, corresponding to an increased vitamin C intake requirement of 35 mg/d in those with high CRP concentrations. Thus, stratifying the vitamin C dose-concentration curve by high vs low CRP concentrations showed a comparable trend to the vitamin C requirements in people with diabetes relative to those without diabetes.

4. Discussion

In this study we interrogated data from the NHANES 2017/2018 cohort and confirmed that people with diabetes had significantly lower vitamin C status than those without, despite consuming an equivalent dietary intake of the vitamin. This suggested that people with diabetes had a higher requirement for the vitamin. We then analysed vitamin C dose-concentration relationships using data from both the NHANES and EPIC-Norfolk cohorts to estimate how much additional vitamin C intake was required by those with diabetes. The data indicated a conservative 1.4- to 1.6-fold higher requirement for vitamin C in people with diabetes to reach comparable adequate vitamin C concentrations to those without diabetes. This corresponded to an additional daily vitamin C intake of ~30-40 mg in people with diabetes. Although smoking is well-known to affect the vitamin C dose-concentration relationship, resulting in higher requirements for smokers [

22], this was accounted for in our study by also assessing non-smokers. Although non-smokers had lower vitamin C requirements in general, the differences in vitamin C requirements between those with and without diabetes were comparable to the total cohorts, i.e. 1.4- to 1.7-fold higher vitamin C requirements for those with diabetes. Despite disparities in the baseline characteristics between the more recent US NHANES cohort and the older UK EPIC-Norfolk cohort, the differences in vitamin C requirements between the groups with and without diabetes were comparable, suggesting a common link between vitamin C requirements and diabetes status.

Body weight has a large impact on vitamin C requirements due to a larger volume requiring a higher dose to reach the same concentration as that observed for a smaller volume [

19]. Vitamin C’s enzyme cofactor and antioxidant functions rely on suitably high concentrations for optimal activity [

32]. The group with diabetes had a significantly higher body weight and BMI than those without diabetes and we have previously shown in the NHANES cohort that higher BMI and body weight tertiles resulted in 1.8- to 2-fold higher requirements for vitamin C than the lower BMI and body weight tertiles [

22]. In the current study, we observed a strong correlation between CRP concentrations and both body weight and BMI, which was even more apparent in the group with diabetes at equivalent weights and BMI. Assessment of the vitamin C dose-concentration relationship stratified by CRP concentrations of low (<1 mg/L) vs high (>3 mg/L) risk for cardiovascular disease indicated a 1.4-fold higher vitamin C requirement for those with high CRP, corresponding to an increased daily vitamin C intake requirement of 35 mg. As such, people with high CRP (>3 mg/L) had comparable vitamin C requirements to people with diabetes, thus, CRP appears to be a suitable surrogate biomarker for determining vitamin C requirements. Of note, inverse associations reported between vitamin C and high-sensitivity CRP [

33], could have BMI or body weight as the common factor, with CRP acting as a proxy biomarker for higher BMI or body weight. Thus, studies showing an impact of vitamin C on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein may be confounded by changes in the participants’ body weight. The associations between vitamin C, high-sensitivity CRP and body weight or BMI need to be investigated in more detail in future studies.

People with greater abdominal fat mass tend to exhibit elevated inflammatory biomarkers and associated oxidative stress [

18]. In the NHANES and EPIC-Norfolk cohorts the people with diabetes had significantly higher waist to hip ratios indicating greater abdominal obesity in this group. Thus, people with diabetes and associated higher abdominal fat mass may be expected to have a greater turnover of vitamin C through its antioxidant activities [

34]. Research has also indicated greater loss of vitamin C in people with diabetes via enhanced renal leak, likely associated with diabetic kidney dysfunction [

20,

21]. We observed a weak inverse correlation between vitamin C concentrations and ACR in the NHANES cohort suggesting possible loss of vitamin C with increasing renal dysfunction. Thus, the enhanced requirements for vitamin C in the group with diabetes likely comprises a combination of higher body weight and enhanced renal dysfunction, with a likely contribution by elevated oxidative stress. Since higher dietary intakes and circulating concentrations of vitamin C have been associated with a lower risk of diabetes morbidity and mortality [

9,

10], increasing vitamin C intake in people with diabetes to account for their higher requirements may help attenuate the progression of the disease to more severe complications. In support of this premise, meta-analyses of intervention studies have indicated that supplementation with vitamin C can improve dysregulated glycaemic and lipid markers and cardiovascular risk factors in people with diabetes [

35,

36,

37]. Furthermore, preliminary research has indicated potential benefit of vitamin C in diabetic foot disease [

38,

39].

Our study findings have important implications for the setting of dietary intake recommendations for vitamin C. The current dietary recommended intake (DRI) for vitamin C in the US is 90 mg/d for men and 75 mg/d for women [

29]. The DRI is meant to meet the vitamin C intake needs of 97.5% of the adult population, with the caveat that there are specific subgroups within the population who have higher intake needs, for example, pregnant and lactating women and smokers [

32]. Although women have a lower DRI based on their lower body weight, there is currently no specific intake category for people with higher body weight, despite the looming twin pandemics of obesity and T2DM [

32]. In the NHANES cohort nearly one in five participants had diabetes, and since body weight/obesity is a factor in the higher vitamin C requirements of people with diabetes, this suggests that a large proportion of the US population is not being catered for by the current US DRIs for vitamin C (which were published more than 20 years ago) [

29]. As such, introduction of a new vitamin C intake category based on higher body weight or higher BMI would better cater for not only those who are overweight/obese, but also those with diabetes.

A limitation of the current research is the non-fasting vitamin C samples. Fasting samples would improve the accuracy of the vitamin C requirement estimates, however, a requirement for fasting samples can be challenging for recruitment of participants to large epidemiological studies. Another limitation is the relatively small size of the diabetes groups in the two cohorts, resulting in relatively large 95% CIs and a more conservative estimate of vitamin C requirements. Thus, larger cohorts of people with diabetes would decrease the 95% CIs and thus increase the difference in requirements between those with and without diabetes, as was observed to a certain extent with the larger EPIC-Norfolk cohort relative to the NHANES cohort. As such, the true vitamin C requirements for people with diabetes may be significantly greater than the 1.6-fold currently estimated.

5. Conclusions

Our research has shown a clear link between diabetes and a higher requirement for vitamin C, with a conservative estimate of 1.4- to 1.6-fold higher vitamin C intake requirement for people with diabetes to reach adequate circulating concentrations of the vitamin. This corresponds to an additional daily vitamin C intake of ~30-40 mg for people with diabetes. These findings have important implications for the setting of global vitamin C dietary intake guidelines. Future dose-finding studies are needed to definitively establish how much vitamin C is required by people with diabetes to compensate for their higher requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.C.; formal analysis, A.C.C.; resources, N.J.W.; data curation, A.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.C.; writing—review and editing, H.L., P.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The EPIC-Norfolk study (DOI 10.22025/2019.10.105.00004) has received funding from the Medical Research Council (MR/N003284/1, MC-UU-12015/1 and MC-UU-00006/1) and Cancer Research UK (C864/A14136).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the NHANES and EPIC-Norfolk studies.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the principal investigators and staff of the EPIC-Norfolk study. We are grateful to all the participants who have been part of the project and to the many members of the study teams at the University of Cambridge who have enabled this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carr, A.C.; Rowe, S. Factors affecting vitamin C status and prevalence of deficiency: A global health perspective. Nutrients 2020, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikimi, M.; Fukuyama, R.; Minoshima, S.; Shimizu, N.; Yagi, K. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of the human nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in man. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 13685–13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.; Frei, B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions? FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englard S, Seifter S. The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid. Annu Rev Nutr. 1986, 6, 365–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young JI, Zuchner S, Wang G. Regulation of the epigenome by vitamin C. Annu Rev Nutr. 2015, 35, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper C, Vissers MC. Ascorbate as a co-factor for Fe- and 2-oxoglutarate dependent dioxygenases: physiological activity in tumor growth and progression. Front Oncol. 2014, 4, 359. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, A.H.; Wareham, N.J.; Bingham, S.A.; Khaw, K.; Luben, R.; Welch, A.; Forouhi, N.G. Plasma vitamin C level, fruit and vegetable consumption, and the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: the European prospective investigation of cancer--Norfolk prospective study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.S.; Sharp, S.J.; Imamura, F.; Chowdhury, R.; Gundersen, T.E.; Steur, M.; Sluijs, I.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Agudo, A.; Aune, D.; et al. Association of plasma biomarkers of fruit and vegetable intake with incident type 2 diabetes: EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study in eight European countries. BMJ 2020, 370, m2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Karp, J.; Sun, K.M.; Weaver, C.M. Decreasing vitamin C intake, low serum vitamin C level and risk for US adults with diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Geng, T.; Lu, Q.; Li, R.; Li, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, S.; et al. Associations of serum vitamin C concentrations with risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with and without type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 Suppl 1, S81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas; Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Wilson, R.; Willis, J.; Gearry, R.; Skidmore, P.; Fleming, E.; Frampton, C.; Carr, A. Inadequate vitamin C status in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Associations with glycaemic control, obesity, and smoking. Nutrients 2017, 9, E997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Spencer, E.; Heenan, H.; Lunt, H.; Vollebregt, M.; Prickett, T.C.R. Vitamin C status in people with Types 1 and 2 Diabetes Mellitus and varying degrees of renal dysfunction: Relationship to body weight. Anitoxidants 2022, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, C.; Discacciati, A.; Åkesson, A.; Orsini, N.; Brismar, K.; Wolk, A. Changes in fruit, vegetable and juice consumption after the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study in men. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.J.; Griffin, S.J.; Sharp, S.J.; Cooper, A.J. Fruit and vegetable intake and cardiovascular risk factors in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Taylor, P.B.; Lunec, J.; Girling, A.J.; Barnett, A.H. Low plasma ascorbate levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus consuming adequate dietary vitamin C. Diabet. Med. 1994, 11, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondia-Pons, I.; Ryan, L.; Martinez, J.A. Oxidative stress and inflammation interactions in human obesity. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 68, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Block, G.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Estimation of vitamin C intake requirements based on body weight: Implications for obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, H.; Carr, A.C.; Heenan, H.F.; Vlasiuk, E.; Zawari, M.; Prickett, T.; Frampton, C. People with diabetes and hypovitaminosis C fail to conserve urinary vitamin C. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2023, 31, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenuwa, I.; Violet, P.C.; Padayatty, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Adhikari, P.; Smith, S.; Tu, H.; Niyyati, M.; et al. Abnormal urinary loss of vitamin C in diabetes: prevalence and clinical characteristics of a vitamin C renal leak. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Factors affecting the vitamin C dose-concentration relationship: implications for global vitamin C dietary recommendations. Nutrients 2023, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkle, J.L. Laboratory Procedure Manual: Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) NHANES 2017-2018. CDC Environmental Health: USA, 2020; p 26 pages.

- Mosslemi, M.; Park, H.L.; McLaren, C.E.; Wong, N.D. A treatment-based algorithm for identification of diabetes type in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab 2020, 9, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentjes, M.A.; McTaggart, A.; Mulligan, A.A.; Powell, N.A.; Parry-Smith, D.; Luben, R.N.; Bhaniani, A.; Welch, A.A.; Khaw, K.T. Dietary intake measurement using 7 d diet diaries in British men and women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer-Norfolk study: a focus on methodological issues. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, A.A.; McTaggart, A.; Mulligan, A.A.; Luben, R.; Walker, N.; Khaw, K.T.; Day, N.E.; Bingham, S.A. DINER (Data Into Nutrients for Epidemiological Research) - a new data-entry program for nutritional analysis in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort and the 7-day diary method. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, J.P.; Keck, E. Fluorometric assay of vitamin C in biological materials using a centrifugal analyser with fluorescence attachment. J Micronutrient Analysis 1989, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.; Luben, R.; Bingham, S.; Oakes, S.; Welch, A.; Day, N. Glycated haemoglobin, diabetes, and mortality in men in Norfolk cohort of european prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition (EPIC-Norfolk). BMJ 2001, 322, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids; National Academies Press: Washington, 2000; p. 529. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand: Executive Summary. Department of Health and Ageing (Ed.) National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, 2006; p 89.

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for vitamin C. EFSA journal. European Food Safety Authority 2013, 11, 3418–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Discrepancies in global vitamin C recommendations: A review of RDA criteria and underlying health perspectives. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021, 61, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarnejad, S.; Boccardi, V.; Hosseini, B.; Taghizadeh, M.; Hamedifard, Z. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials: The impact of vitamin C supplementation on serum CRP and serum hs-CRP concentrations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 3520–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courderot-Masuyer, C.; Lahet, J.J.; Verges, B.; Brun, J.M.; Rochette, L. Ascorbyl free radical release in diabetic patients. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 2000, 46, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Hosseini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Salamat, S.; Nadery, M.; Yarmand, S.; Zamani, M.; Wong, A.; et al. The effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkhah, Z.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Naeini, F.; Clark, C.C.T.; Asbaghi, O. Does vitamin C supplementation exert profitable effects on serum lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes? A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Keske, M.A.; Wadley, G.D. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, K.P.; Intine, R.; Wu, S. Vitamin C and the management of diabetic foot ulcers: a literature review. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, S33–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, J.E.; Girgis, C.M.; Lau, T.; Vicaretti, M.; Begg, L.; Flood, V. Vitamin C improves healing of foot ulcers; A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).