INTRODUCTION

‘Bystanderism’ is social psychological theory that examines determinants that promote or inhibit a person's willingness to help someone in an emergency situation. [

1] It has become a predominant phenomenon used to explain how behavioural tendencies to act prosocially are influenced by a particular situation. [

2,

3] One of the most important areas in which the concept of bystanderism has been applied is out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). A cardiac arrest is a life-threatening medical event in which a person’s heart stops beating, and the person becomes unconscious and collapses. [

4] The chances of a victim surviving drop by 10% for every minute they do not receive help. [

5] The probability of surviving a cardiac arrest improves substantially if someone who witnesses the collapse performs cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). [

6,

7] CPR provides some degree of systemic circulatory flow, mitigating irreversible organ and neurological injury until normal circulation can be restored. [

8]

A “bystander” or “lay responder”, is defined as “anyone who responds in any way to aid a victim of cardiac arrest (calling 9-1-1, retrieving an AED, performing CPR) and is not responding as part of an organized emergency medical response”. [

9] Several organizations around the world have devoted substantial resources to innovate training and education to increase lay responder interventions in OHCA. [

10,

11,

12] Bystander CPR rates have increase from 15% to 30% in many countries over the last 20 years [

13], however, these gains are at risk of being lost in the face of fear of transmission of the SARS-COV-2 virus during the recent global COVID-19 pandemic. [

14,

15] The COVID-19 pandemic was not the only time bystander CPR rates have been at risk of decline. During the SARS outbreak in 2007, several studies were published looking at the impact of transmission risk on public willingness to respond to an OHCA. Lam et al. reported a statistically significant drop in the willingness of people to do CPR between the pre-SARS and post-SARS era. [

16] Previous qualitative studies have identified general fear of disease transmission as a key barrier to bystander CPR however none have been conducted during a global pandemic. [

17,

18] Previous goals to improve rates of bystander CPR in the community are in jeopardy as our new normal threatens to reduce current bystander CPR rates in Canada and abroad.

Our task as health services researchers is to understand the current public perception of CPR and the associated risk, and how we can best modify our messaging, social media and education to address those perceptions. [

19] This survey study was designed to examine the opinions and perceptions of the Canadian public on bystanderism as it relates to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic with a view to understanding the implications of those opinions on our expectations of bystanders during, and after the pandemic.

METHODS

Survey Design

In order to capture a pan-Canadian sample of the general public, we engaged with a well-established public opinion polling vendor, IPSOS (

www.ipsos.com), to conduct a robust survey on public willingness to do bystander CPR in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic. This study was approved by the [insert name here after peer review] Research Ethics Board (#21-0037).

The survey was designed by the research team and was based on previous surveys done regarding public willingness to do bystander CPR. [

20] A total of 19 closed ended and 2 open ended questions were included to capture concepts related to willingness to perform bystander CPR, barriers, and facilitators to doing bystander CPR given COVID-19 pandemic and future needs for CPR training. Respondents were presented with a single concept definition of cardiac arrest and CPR in text format. The survey was pilot tested with 5 potential public respondents, with feedback incorporated into the final survey design. A copy of the full survey as delivered is included in Appendix A.

Study Context, Sampling & Recruitment

This survey was conducted in March 2022. At that time, the COVID-19 Pandemic had been surging in Canada for a full two years and the Omicron variant which caused an uptick in cases and concern across the world had just passed its peak. At that time, there were approximately 6,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported daily in Canada (

Figure 1 [

21]) and in February 2022, the Government of Canada as well as provincial and territorial governments announced adjustments to public health measures and easing of travel restrictions as they looked to transition away from the crisis phase of the pandemic. [

22]

IPSOS facilitated nation-wide sampling and recruitment for the survey via the Ipsos eNation Canadian Online Omnibus survey platform. Data was collected through random sampling of their 800,000+ member online panel. The IPSOS online panel is recruited and maintained utilizing double and triple opt-in screening processes to ensure maximum return from an engaged and representative audience. The panel is updated regularly, and non-responders are removed. Applicants are rigorously vetted during a 30-day trial period to ensure quality of respondents. [

23]

The study sample was designed to be nationally representative of the adult Canadian population. Data were weighted on gender, age, region, and income, based on census information, to ensure that the sample’s composition reflected that of the reference population. The Canadian sampling process included an additional sampling of French-speaking respondents in Canada to provide a base for analysis within that group. The margin of error associated with this technique on a sample size of 1000 adults is <±3.1% relative to the result that would be attained after polling the entire population, 19 times out of 20. [

23]

Sample Size and Inclusion Criteria

The goal sample size was n=1000 respondents based on IPSOS’ experience with similar surveys and resources available for the study. To be eligible for inclusion in this survey, all potential respondents had to be 18 years of age or older. Surveys were available in both English and French; respondents selected their preferred language at the beginning of the survey.

Analysis

The software package SPSS 6.0.1 was used to conduct all analyses. Descriptive statistics are used to characterize the study sample. Analysis of the survey responses was carried out using descriptive statistics and comparison of groups (age, gender, family situation, and level of education) based on responses to primary questions and we report binary questionnaire answers as percentages.

Responses to the outcome variables, which were reported on a Likert scale, were dichotomized with specified cut-points set a priori. This was done to simplify the interpretation of the weighted-logistic regression analysis. For example, individuals who responded to the comfort-level questions with “very comfortable,” “somewhat comfortable,” or “neither comfortable nor uncomfortable” were coded as having “no objections.” Individuals who responded with “somewhat uncomfortable” and “very uncomfortable” were coded as feeling “uncomfortable”.

Open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively. Due to the large sample size and number of open-ended responses requiring coding, a broad coding framework [

24] was adopted which allowed us to group responses which expressed similar yet not necessarily identical ideas into larger descriptive categories.

RESULTS

A total of n=1,000 surveys were completed by Canadian adults from March 11 to March 14, 2022 using the IPSOS eNation Canadian Online Omnibus survey platform.

Respondent Demographics

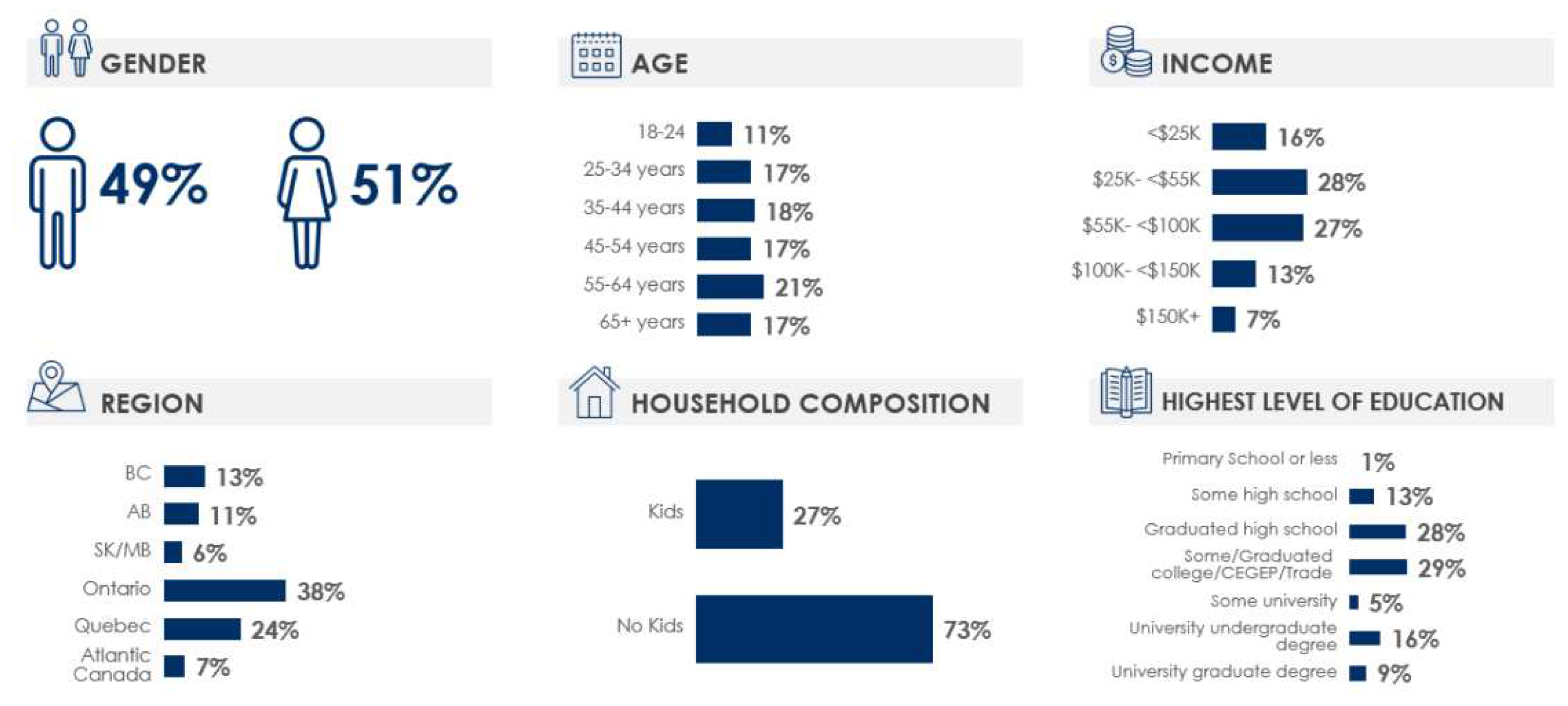

Gender was split very evenly in the respondent sample (49% female) and the majority of respondents were married (73%) with 27% reporting having children. The age of respondents was also split evenly across decades from 18 to 65+ and approximately a third graduated high school, and two-thirds had post-secondary education. Only 49% had previously taken CPR training and among those who had previous CPR training, 36% said it has been longer than 10 years since their last training. Relatively few (25%) who have received CPR training have done so within the last two years. Additional demographics of the respondents are outlined in

Figure 1.

Recognition of Cardiac Arrest

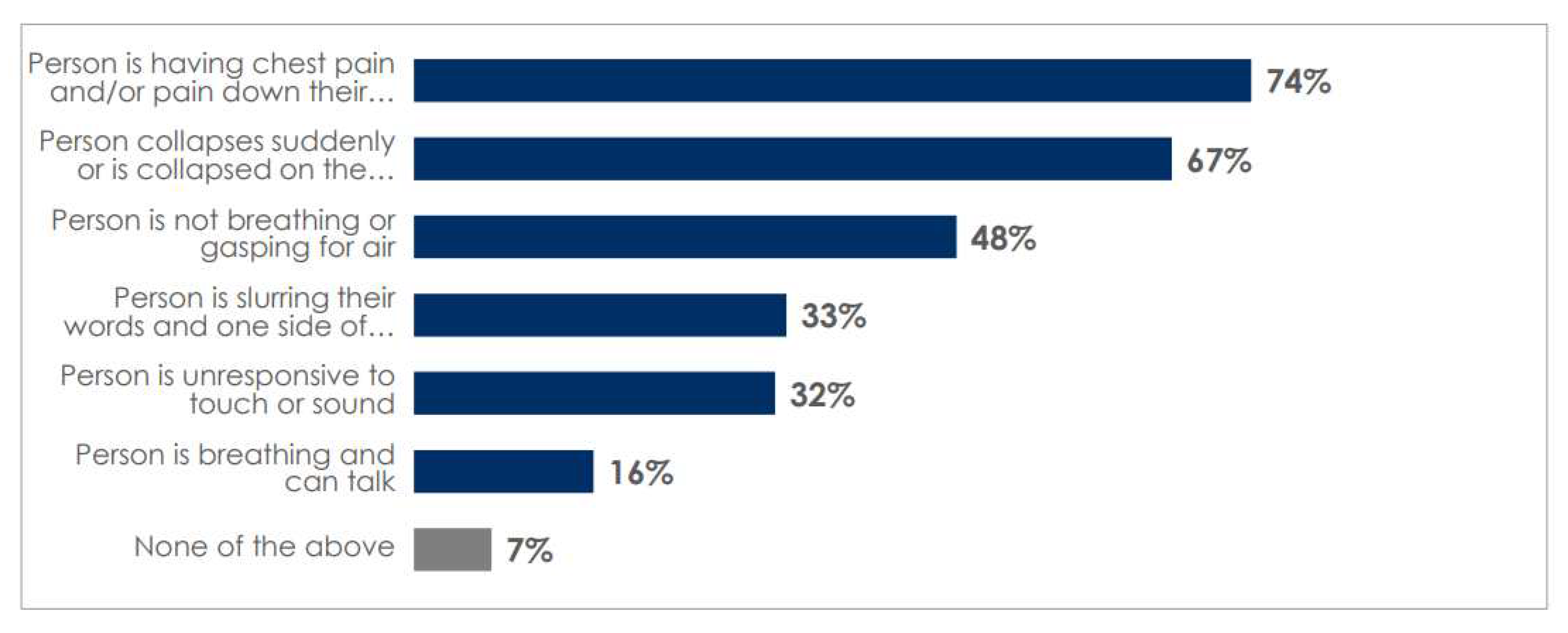

Almost half of Canadians surveyed (43%) personally knew someone who had suffered a sudden cardiac arrest. When provided with a list of possible symptoms, Canadians selected chest pain and/or pain down the arm as the most common symptom of cardiac arrest (74%) which is incorrect (

Figure 2). Men were most likely to recognize the signs of cardiac arrest, as were respondents over age of 35 years. The second most common sign of cardiac arrest selected by respondents was a person suddenly collapsing on the ground (67%) which is accurate.

Willingness to Respond to Cardiac Arrest

Over half of Canadians polled (56%) say they would respond to someone having cardiac arrest at the time of the survey. Canadians over the age of 55 indicated they would be more likely to not wait/stand by for someone else to act compared to those under 55 years of age. Results also indicate that familiarity with the victim impacts willingness to respond to someone experiencing cardiac arrest in public. Canadians are more likely to respond to a familiar person or a family member who has collapsed and might be experiencing cardiac arrest than they are a stranger. Just over 77% of Canadians would perform chest compression only CPR on a familiar person, compared to 56% who would do so for a stranger. A similar proportion (77%) are willing to perform mouth-to-mouth on a familiar person but only 35% would perform it on a stranger and 72% of Canadians are likely to use an AED on a family member/familiar person but only 57% would use one on someone they do not know (57%).

In our survey 61% of men and 52% of women would perform chest compression only CPR on a stranger, as well as check for breathing/pulse on a stranger (73% of men vs. women of 65%). Eighty percent (80%) of male respondents would perform mouth-to-mouth on a family member/familiar person compared to only 73% of female respondents and in the case of a stranger, willingness dropped by almost half in both groups (41% and 29% respectively).

Impact of COVID-19 on Bystanderism during Cardiac Arrest

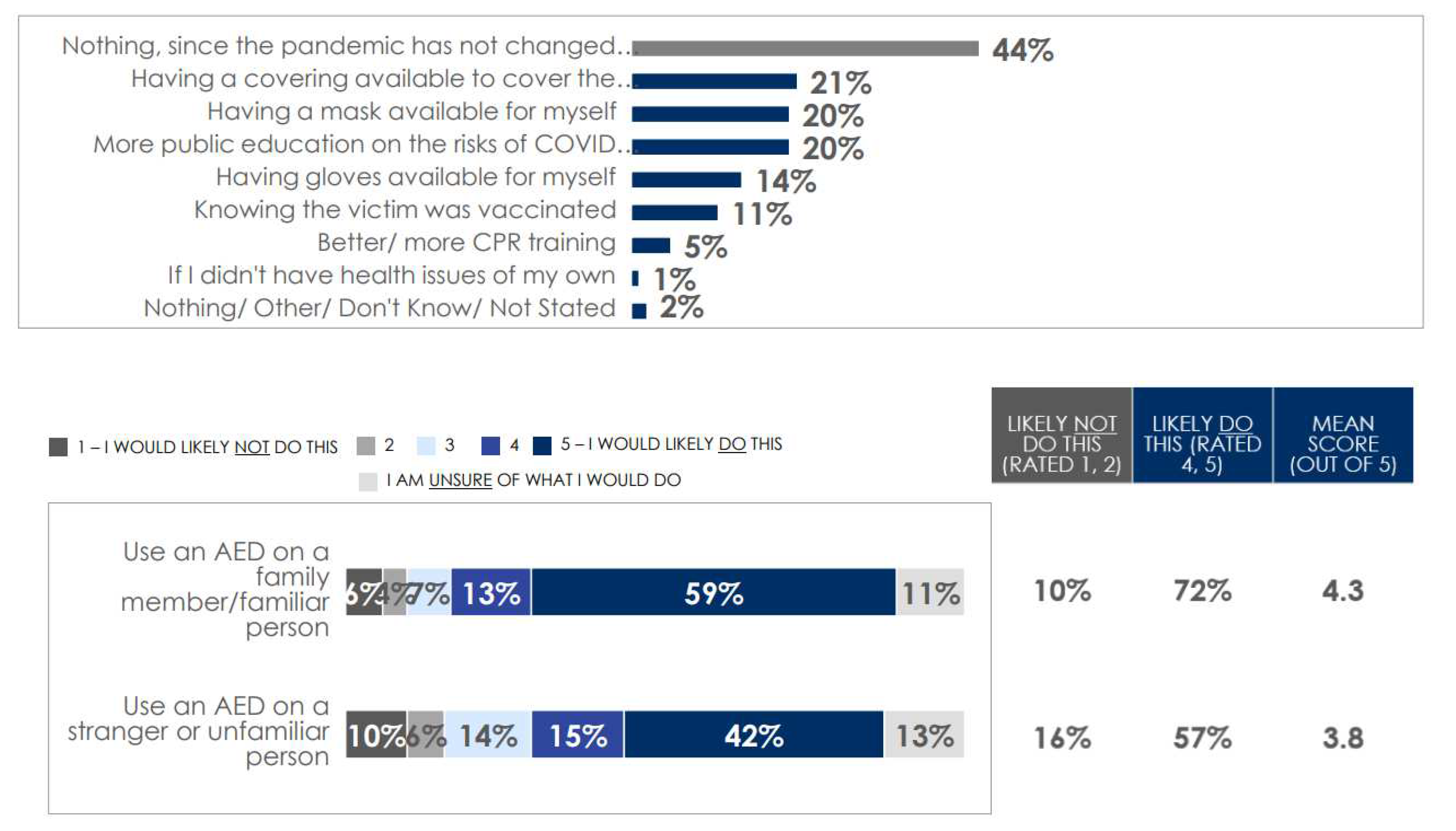

The majority of respondents (56%) said they felt the pandemic has changed their willingness to respond to someone in cardiac arrest. About a third of respondents indicated that having something available to cover the victim’s mouth and nose (21%), having a mask for themselves (20%) and increasing public education about the risks of COVID-19 transmission while performing CPR (20%) would increase their willingness to perform CPR (

Figure 3). More women (24%) and university graduates (27%) would want a covering for the victim’s mouth/nose, have a mask available (24% each), as well as like to see more public education (23% and 26% respectively). Twelve percent (12%) of respondents said that their willingness to respond has definitely changed during the pandemic.

Impact of knowing Vaccination Status

Vaccination status and the presence of the new variants (Omicron was newly identified at the time of the survey) have largely not affected Canadians’ willingness to perform CPR. Just over half of the respondents (57%) stated that knowledge of a victim’s vaccination status would not affect of how they would respond or act. Approximately one in three (32%) responded that it might affect their decision to act/respond with the most common respondents selecting this answer being those aged 55+ (38%). Only 11% of respondents said it would definitely affect their decision to act/respond.

Impact of appearance of new variants

At the time of the survey (March 2022), the Omicron variant had been identified as potentially more virulent strain of COVID-19 [

25]. Over half of Canadians (57%) stated that their willingness to respond did not change with the presence of the Omicron variant; high school graduates (61%) and those with post secondary experience (58%) most commonly stated that their willingness had not changed. Among those with a post-secondary education, 40% said they would respond to someone experiencing cardiac arrest despite the spread of the new variants. Among younger respondents (18–34-year-old) 18% say their willingness to act would be influenced by new variants such as Omicron.

CPR Training & AED Use

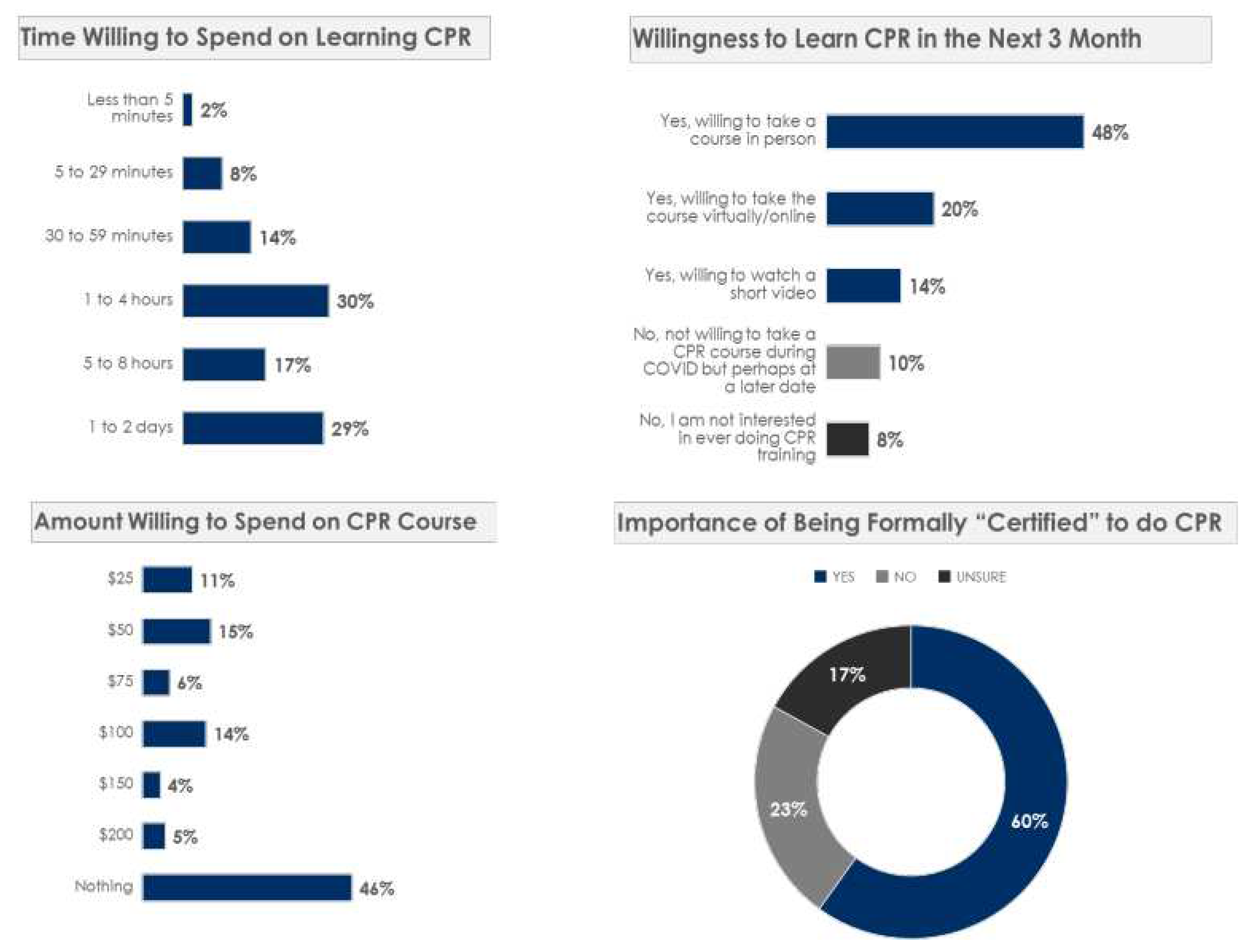

When asked about CPR certification, 60% of Canadians feel that certification is important and half of those polled (49%) have taken CPR training in the past. One in three (28%) have never taken any type of CPR training before. Almost half (48%) were willing to take a course in person in the next three months, 20% would prefer to take it online.

While most respondents said it is important to be certified in CPR and are willing to take a CPR training course, half indicated they did not know where they can go to take a course. Moreover, while most Canadians prefer to take training in person, roughly half (46%) are not willing to pay for it. Younger generations prefer to take a virtual course than those over the age of 55 years. Over one quarter know that the Canadian Red Cross offers CPR training, and one-fifth know that St. John Ambulance also offers courses on CPR.

When asked about their comfort with using an automatic external defibrillator (AED), 46% reported that a lack of experience and/or knowledge about the device was a substantial barrier to them using an AED. Nearly three quarters (72%) of Canadians would use an AED on a familiar person/family member. However, this proportion decreases to 57% when helping a stranger or unfamiliar person. Results are summarized in

Figure 4.

Discussion

In summary there were five key findings from this pan-Canadian survey: 1) the ability to recognize cardiac arrest remains a point of confusion for the lay public, 2) at the time of the survey only about half of respondents said they would respond to someone having cardiac arrest, 3) the majority of respondents said the pandemic has changed their willingness to respond to someone in cardiac arrest, 4) willingness to use an AED is low and the greatest barrier was reported as lack of experience, and lastly 5) most Canadians say it is important to be certified in CPR and are willing to take a CPR training course, however only half are willing to pay for it and half do not know where to find a course.

This pan-Canadian survey provides a robust look at the mindset of the general public with regard to willingness to performing bystander CPR in a pandemic context. Since the onset of the pandemic, bystanders' willingness to perform CPR has been a debated topic in the scientific community, especially among those involved in lay education. [

26,

27] Recognizing the potential for chest compressions to produce aerosolized matter, CPR instructions all over the world were modified to include safety measures for bystanders while still encouraging the lay public to respond to the life-threatening emergency before them. Despite new guidance and reassurance, there has still been a significant reduction in bystanders providing CPR and in the use of public access to defibrillation (PAD) in many parts of the world. [

28,

29,

30] Given that bystander CPR is significantly associated with improved OHCA survival, this may translate into increased mortality after OHCA and a worst neurologic outcome for survivors—a devastating downstream effect.

Data on attitudes towards bystander CPR during the COVID-19 pandemic has been published previously. [

20,

31,

32,

33] Grunau et al. [

20] published the results of a large international social media survey to investigate the effect of the current COVID-19 pandemic on the willingness of bystanders to provide CPR to OHCA victims in 2020. A total of 1360 participants responded from 26 countries and the results indicated a significant decrease in the willingness to provide CPR during the pandemic across all resuscitation steps especially, but not surprisingly, providing rescue breaths to a stranger. However, basic personal protective equipment (e.g. facemask or mouth-covering) being made available increased willingness to respond. In a similar internet-based, social media survey study conducted in Taiwan also early in the pandemic (2021), 61% (n-822) of respondents had negative attitudes toward performing bystander CPR. [

31] The adjusted predictors in that sample were younger age, being a man, and being a health care provider and 23.5% said they would perform CPR if they wore facemasks. Although our results are similar quantitatively, the breadth and timing of our data collection much further along in the pandemic context, allows us to speak directly to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across a potentially more representative sample of the Canadian population. Our results show similar differences in perception across age and gender demographics and the rise in concern about responding with new, more potent variants are notable. The ideas of providing mask coverings for victims and responders and increased public education about the risk of COVID-19 transmissions in the context of CPR persist and may be the way to encourage more Canadians to perform CPR. Based on the results presented here we feel confident in our ability to recommend more demographically tailored and contextually relevant improvements in CPR & AED training, communication about bystander CPR in the COVID-era and public health approaches to decreasing fear and anxiety about disease transmission. In terms of CPR and AED training, our results support the overall move to compression-only CPR however CPR training needs to be free, accessible in more formats (both in-person and virtual) and include more focus on recognition of cardiac arrest and experience with AEDs.

Our results represent data on a more current state of the union given the status quo with which the pandemic condition now exists. In the COVID-19 pandemic, as in other pandemics, fear, anxiety, and worries have been the major psychological consequences. [

34,

35] Now that COVID-19 is appearing to be more endemic [

36,

37], fear of disease transmission during CPR may become more common [

25] and therefore investment in combatting its impact is crucial.

Strengths & Limitations

The strengths of this study include the large sample size and a robust sampling strategy that was pan-Canadian and weighted according to Canadian population census. We also were able to provide the survey in both official languages.

That said, our study is has limitations, most of which are common with survey research. All sample surveys and polls are subject to sources of error, including, but not limited to coverage error, measurement error and volunteer bias. Although participants who volunteer to be part of the Ipsos Omnibus may be systematically different than the true general public, we did our best to reduce the impact of this bias with a large and diversified sample size. Our survey was also conducted using a Web-based survey platform, which may create a bias toward individuals with computer literacy and access to the Internet. Due to the nature of the panel survey approach, we were unable to calculate the traditional response rate. Naturally, opinions may differ between responders and non-responders to the survey, so our results may have been subject to selection bias.

Finally, the pandemic circumstances are ever changing and so it is difficult to continuously monitor changes that may be happening in public opinion. We also do not have a direct comparison group of pre-pandemic attitudes toward bystander CPR and therefore we cannot comment on changes in attitudes over time. That said, the pandemic is still very present in the day-to-day life of Canadians and so we feel that our results remain relevant and provide insight for future planning and educational design.

Conclusion

Bystander CPR is an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victim’s best chance of survival and so our understanding of how we encourage more citizens to respond given the current realities is more crucial than ever. Wider dissemination of the growing evidence on the safety of CPR in the context of COVID-19 and resuscitation training courses implemented with specific CPR manoeuvres to reduce the risk of infection should be implemented to continued uncertainty and erosion in bystander CPR culture.

References

- Darley, J.M.; Latane, B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 8, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latané, B.; Rodin, J. A lady in distress: Inhibiting effects of friends and strangers on bystander intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 5, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B.; Nida, S. Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 89, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiac Arrest - https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/cardiac-arrest#:~:text=Cardiac%20arrest%20occurs%20when%20the,the%20heart%20from%20pumping%20blood. Last accessed September 26, 2023.

- Larsen, M.P.; Eisenberg, M.S.; O Cummins, R.; Hallstrom, A.P. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A graphic model. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1993, 22, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragholm, K.; Wissenberg, M.; Mortensen, R.N.; Hansen, S.M.; Hansen, C.M.; Thorsteinsson, K.; Rajan, S.; Lippert, F.; Folke, F.; Gislason, G.; et al. Bystander Efforts and 1-Year Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiguchi, T.; Okubo, M.; Nishiyama, C.; Maconochie, I.; Ong, M.E.H.; Kern, K.B.; Wyckoff, M.H.; McNally, B.; Christensen, E.F.; Tjelmeland, I.; et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest across the World: First report from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Resuscitation 2020, 152, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipani S, Bartolozzi C, Ballo P, Sarti A. (2019) Blood flow maintenance by cardiac massage during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Classical theories, newer hypotheses, and clinical utility of mechanical devices. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 20(1):2-10.

- Dainty, K.N.; Colquitt, B.; Bhanji, F.; Hunt, E.A.; Jefkins, T.; Leary, M.; Ornato, J.P.; Swor, R.A.; Panchal, A. ; on behalf of the Science Subcommittee of the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee Understanding the Importance of the Lay Responder Experience in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E852–E867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada - https://www.heartandstroke.ca/how-you-can-help/learn-cpr. Last accessed September 26, 2023.

- Red Cross - https://www.redcross.org/take-a-class/cpr Last accessed September 26, 2023.

- St. John’s Ambulance - https://www.sja.org.uk/courses/workplace-first-aid/cpr-certificate/cpr-certificate/. Last accessed September 26, 2023.

- Yan, S.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zong, Q.; Chen, S.; Lv, C. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranata, R.; Lim, M.A.; Yonas, E.; Siswanto, B.B.; Meyer, M. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest prognosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, M.F.; Mohamad, M.H.N.; Sahar, M.A.; Juliana, N.; Abu, I.F.; Das, S. Readiness of Bystander Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (BCPR) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam KK, Lau FL, Chan WK, Wong WN. (2007) Effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on bystander willingness to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)--is compression-only preferred to standard CPR? Prehospital Disaster Med. Jul-Aug;22(4):325-9.

- Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Eigel B, et al (2008). Reducing barriers for implementation of bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association for healthcare providers, policymakers, and community leaders regarding the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2008; 117:704–709.

- Charlton, K.; Blair, L.; Scott, S.; Davidson, T.; Scott, J.; Burrow, E.; McClelland, G.; Mason, A. I don’t want to put myself in harm’s way trying to help somebody: Public knowledge and attitudes towards bystander CPR in North East England – findings from a qualitative interview study. SSM - Qual. Res. Heal. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Using Social Media Platforms for the Greater Good—The Case for Leveraging Social Media for Effective Public Health Messaging. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2319682–e2319682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunau, B.; Bal, J.; Scheuermeyer, F.; Guh, D.; Dainty, K.N.; Helmer, J.; Saini, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Brar, N.; Sidhu, N.; et al. Bystanders are less willing to resuscitate out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims during the COVID-19 pandemic. Resusc. Plus 2020, 4, 100034–100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/canada/.

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2022/02/government-of-canada-lightens-border-measures-as-part-of-transition-of-the-pandemic-response.html.

- ipsosglobaladvisor. IPSOS Global Advisor http://www.ipsosglobaladvisor.com/methodology.aspx. Last accessed September 1, 2023].

- Saldaña J: The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2009, London: Sage.

- Thakur V, Ratho RK. OMICRON (B.1.1.529): A new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern mounting worldwide fear. J Med Virol. 2022 May;94(5):1821-1824.

- Baldi E, Contri E, Savastano S, et al. (2020) The challenge of laypeople cardio-pulmonary resuscitation training during and after COVID-19 pandemic. Resuscitation. 152:3-4.

- Kapoor I, Prabhakar H, Mahajan C. (2020) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in COVID-19 patients - To do or not to? J Clin Anesth. 65:109879.

- Nishiyama, C.; Kiyohara, K.; Iwami, T.; Hayashida, S.; Kiguchi, T.; Matsuyama, T.; Katayama, Y.; Shimazu, T.; Kitamura, T. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on bystander interventions, emergency medical service activities, and patient outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Osaka City, Japan. Resusc. Plus 2021, 5, 100088–100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, E.; Sechi, G.M.; Mare, C.; Canevari, F.; Brancaglione, A.; Primi, R.; Palo, A.; Contri, E.; Ronchi, V.; Beretta, G.; et al. Treatment of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the COVID-19 era: A 100 days experience from the Lombardy region. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0241028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelson DP, Sasson C, Chan PS, et al. (2020) American Heart Association ECC Interim COVID Guidance Authors. Interim guidance for basic and advanced life support in adults, children, and neonates with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: from the Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Get with The Guidelines–Resuscitation Adult and Pediatric Task Forces of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 141:e933–e943.

- Chong, K.-M.; Chen, J.-W.; Lien, W.-C.; Yang, M.-F.; Wang, H.-C.; Liu, S.S.-H.; Chen, Y.-P.; Chi, C.-Y.; Wu, M.C.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; et al. Attitude and behavior toward bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation during COVID-19 outbreak. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0252841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Iio, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Kozai, H.; Tanaka, M.; Aoike, M.; Kawamura, H.; Seguchi, M.; Tsurudome, M.; Ito, M. Willingness and Predictors of Bystander CPR Intervention in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey of Freshmen Enrolled in a Japanese University. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scquizzato, T.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Ristagno, G.; Semeraro, F. The other side of novel coronavirus outbreak: Fear of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2020, 150, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Généreux, M.; Roy, M.; David, M.D.; Carignan, M.; Blouin-Genest, G.; Qadar, S.Z.; Champagne-Poirier, O. Psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: main stressors and assets. Glob. Heal. Promot. 2021, 29, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, R. COVID-19 and mental health: Preserving humanity, maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endemic Covid: Is the pandemic entering its endgame? January 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-59970281. Last accessed September 26, 2023.

- Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. (2020) Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the post-pandemic period. Science. 368(6493):860-868.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).