1. Introduction

With the rapid advancements in maternal and neonatal healthcare, the primary focus has shifted from merely reducing maternal and neonatal mortality to improving the quality of midwifery services and optimizing the childbirth management, so as to promote natural birth and positive childbirth experience [

1]. The second stage of labour is an important component of the natural labour and plays a vital role on ensuring the health of the women and newborn [

2]. Further, the duration of the second stage of labour usually serves as a core element of the management in this period [

3]. According to The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin, the mean duration of the second stage of labour is 54 minutes for primiparous women and 19 minutes for multiparous women, with an additional 25 minutes for women with epidural analgesia [

4]. A “prolonged second stage” is associated with multiple negative maternal outcomes, such as instrumental assisted birth, conversion to cesarean section [

3]. In addition, it can also result in severe perineal lacerations, haemorrhage and intrauterine fetal distress [

5].

Improved scientific management of maternal positions in the second stage of labour has the potential to influence the duration of the second stage of labour and other maternal and neonatal outcomes [

6]. As recommended by World Health Organization (WHO), women could choose the appropriate upright birth positions of their own free during the second stage of labour for a positive childbirth experience [

7]. Sitting position, as an important upright position [

8], has gained more attention in recent research studies exploring its impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes [

9,

10]. However, the findings of existing studies exploring the effects on the maternal and neonatal outcomes of the sitting position in the second stage of labour remain inconsistent [

11,

12]. A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial compared the duration of the second stage of labour in nulliparous women who gave birth on a birth seat with those in any other position, and the results showed a significant shorter second stage of labour for women in the sitting position [

13]. The result aligns with another study conducted in China that compared the maternal and neonatal outcomes between women assigned to the sitting position group and those in the lithotomy position group during the second stage of labour [

14]. However, Rezaie et al. [

15] conducted a comparative study to investigate the effects of three birth positions (sitting, squatting and supine position) during the second stage of labour on maternal outcomes, and they observed a prolonged phase of the second stage of labour in the sitting group. Additionally, another randomized control trial [

16] reported that no significant difference in the duration of the second stage of labour between women who gave birth in a vertical birth chair and those in the lithotomy position. Studies reported mixed results regarding the effects of sitting position as compared to the lithotomy position on other maternal and neonatal outcomes. Some studies reported that women who gave birth in the sitting position had lower rates of instrumental assisted births, reduced blood loss and higher Apgar scores [

12,

17], but they were more likely to have an episiotomy and perineal laceration compared with those in the lithotomy position [

18]. However, other studies reported that there was no significant difference in terms of the birth mode [

19], perineal laceration and episiotomy as well as mean Apgar scores [

11,

16] between the sitting position group and the lithotomy position group, but a high rate of postpartum haemorrhage between 500 ml and 1000 ml was associated with the sitting position [18-20]. Therefore, it appears that current research regarding the influence of sitting position during the second stage of labour on the maternal and neonatal outcomes remain controversial, underscoring the need for further high-quality studies to investigate this topic.

Childbirth experience has been considered as an important aspect to ensure a high-quality maternal care based on the recent WHO recommendations, which could reflect women’s expectations and feelings across the labour process [

7]. However, there is a lack of studies to explore the effects of maternal positions on the childbirth experience. Ganapathy et al. [

12] randomly allocated 200 primiparous women in the sitting or the lithotomy position and assessed the maternal birthing experiences using a self-designed questionnaire. The findings showed that a higher number of women in the sitting position group reported feeling comfortable and had a positive perception of participation compared to the lithotomy position group. Farahani et al. [

21] conducted a quasi-experimental study to compare the mother’s experiences (feeling of birth, pain, anxiety, and fatigue) of adopting different positions during the second stage of labour, these positions included lithotomy position, squatting position and kneeling position. However, the results showed no significant differences in any aspect of mother’s experience among three groups. Currently, there is an insufficient number of studies comparing the sitting position to the lithotomy position during the second stage of labor in terms of childbirth experience assessed using valid scales. More research in this area is needed in the future. Thus, the aim of our study was to explore the effects of using sitting position versus lithotomy position during the second stage of labour on maternal and neonatal outcomes, as well as women’s childbirth experience. The findings from this study could shed light on birth position management in the clinical practice and help to improve the quality of the maternal care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and Participants

This was a prospective cohort study conducted from February to June 2023 in Beijing China.Women were eligible if they: (1) intended to have a spontaneous vaginal birth; (2) aged between 20–35 years old; (3) had a gestational age range from 37 + 0 to 41 + 6 weeks; (4) had a singleton cephalic presentation; (5) can communicate normally and participate voluntarily. They were excluded if they had: (1) abnormal fetal position (e.g., persistent occipital-transverse and occipital-posterior position, etc.); (2) severe pregnancy or childbirth complications, such as severe eclampsia, heart disease, cephalic presentation dystocia, etc. (3) pelvic stenosis; (4) precipitate labour. The eligible women were informed the details of our study by the attending midwife and decided whether or not to participate in the study. Finally, the participants were divided into the sitting position cohort and the lithotomy position cohort of their own free will. This study obtained ethical approval from the institutional review board (2022PHB188-001), and obtained written consent from all participants. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for reporting observational studies was adopted to report our study [

22].

2.2. Study Variables

Demographic and clinical baseline data included parity, maternal age, education, gestation weeks, caesarean section history, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain, position of foetus, oxytocin use, labour analgesia, baby’s birth weight and length, position in the first stage of labour, and the complications (low-risk). The primary outcome of this study was the duration of the second stage of labour. Secondary outcomes included the birth mode (including spontaneous vaginal birth, instrumental assisted birth and cesarean section), episiotomy, perineal injuries including the complete and laceration (degree of severity was according to ACOG guideline [

23]), postpartum 2 h-haemorhage(>500 ml), newborn Apgar score at five and ten minutes postpartum, artery pH and the childbirth experience. Refer to previous studies [

10,

24,

25], the identified possible confounders included gestation weeks, age, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain, baby’s birth weight, oxytocin use, epidural analgesia and low-risk complications, which might impact the effects of the maternal positions on maternal and neonatal outcomes.

2.3. Data collection

The information regarding maternal demographic and clinical baseline data was prospectively collected by reviewing hospital records. Data for study outcomes were similarly gathered from hospital records after childbirth and recorded in the pre-designed questionnaire. In addition, women were asked to complete the Chinese version of the Childbirth experience questionnaire (CEQ) within 24 hours of the birth to obtain their childbirth experience [

26]. The Childbirth experience questionnaire (CEQ) [

27] was developed in Swedish by Dr. Dencker et al. it has been wildly used as a reliable instrument to assess the women’s perceptions and experience during childbirth. The adapted Chinese version of the CEQ contained four dimensions with 19 items to evaluate women’s professional support, self-ability, self-perception and the sense of participation. The high scores demonstrate the better childbirth experience.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome-duration of the second labour, was selected to conduct sample size calculations [

28]. According to a similar study [

29], the standard deviation (SD) of the duration of the second stage of labour was defined as 22 minutes, and the mean value of the exposed group was 26.36 minutes, while 35.03 minutes of the control group. Assuming an alpha at 0.05, a power of 90% and two-tailed. Eventually, a total of 216 participants were needed. SPSS version 27.0 software [

30] was used for statistical analysis. Demographic and clinical baseline data were summarized with descriptive statistics. Count data, such as the rates of perineal laceration and episiotomy, etc., were analyzed through the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for comparisons between groups. For continuous variables, such as the duration of the second stage of labour, the student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitne U test were utilized to compare the differences between groups. Multivariate linear regression and logistic regression were employed to control possible confounders [

10,

24,

25] when comparing the difference on primary and secondary outcomes between the two cohorts. The sample of the multiparous women was limited to the multivariate regression analysis of the maternal and neonatal outcomes. All comparative analyses were recognized as statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

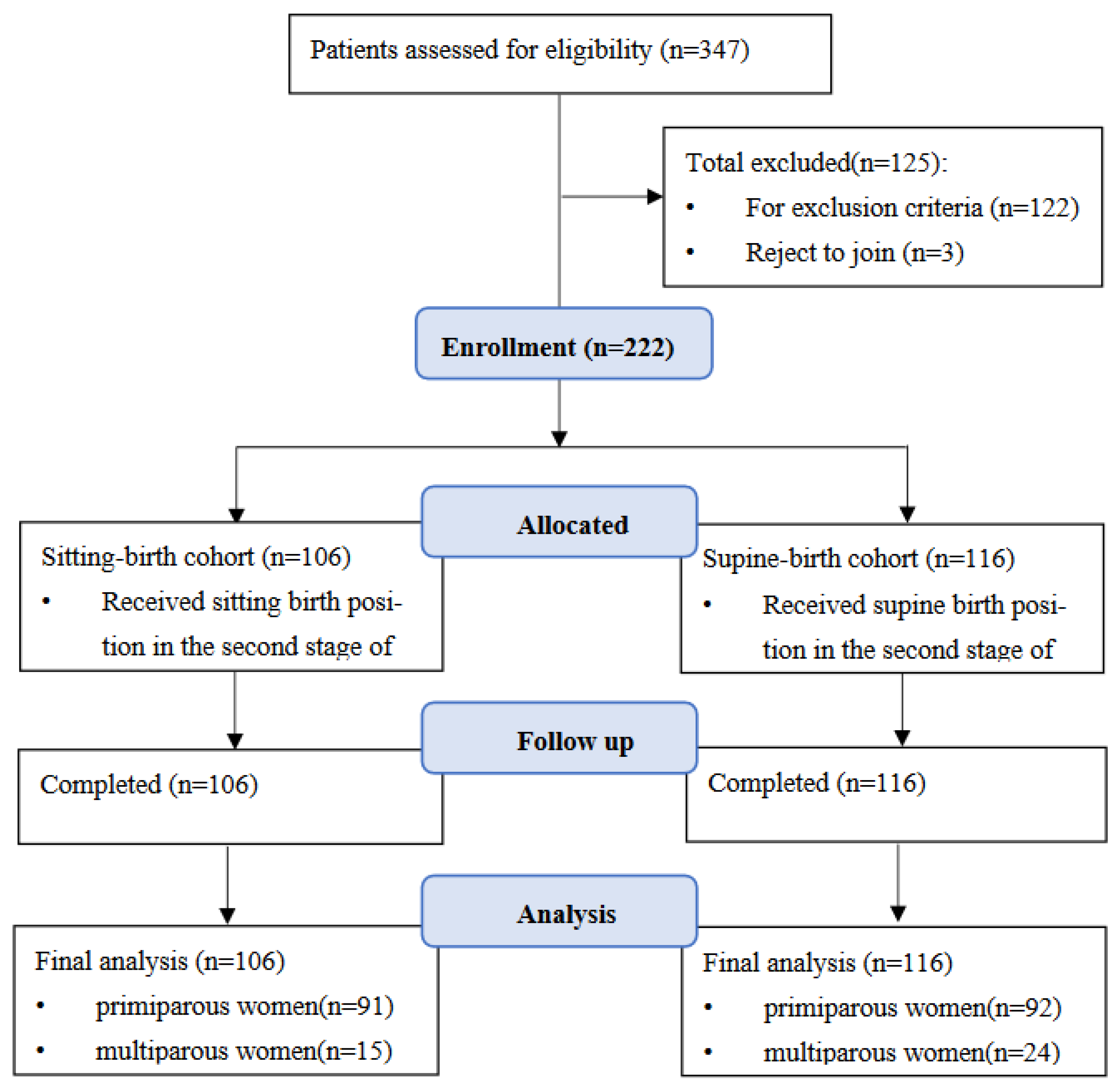

A total of 347 women were approached, of these, 125 women were excluded for not fitting the inclusion criteria or refusing to participate. As a result, 222 women (183 primiparous women, 39 multiparous women) participated in the study, 206 in the sitting position cohort and 216 in the lithotomy position cohort. Among primiparous women, there were 91 women in the sitting position cohort and 92 women in the lithotomy position cohort. For multiparous women, 15 were in the sitting position cohort, and 24 in the lithotomy position cohort. The Flowchart of enrolment is shown in

Figure 1. Of these 222 participants, the mean age was 30.97 (SD = 2.66) years, and the mean gestation week was 39.69 (SD = 0.97) weeks. Most participants have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and had no caesarean section history. The mean maternal weight gain during pregnancy was 14.02 (SD = 7.58) kg, and all the fetal positions were occiput anterior. Detailed demographic characteristics and birth information by parity and position are shown in

Table 1. The demographic and clinical baseline data were generally similar between the sitting position and supine-birth cohort, regardless of parity.

3.2. The comparison of the primary and secondary outcomes of childbirth between cohorts

Table 2 presents the comparison results of maternal and neonatal outcomes between the two cohorts. Among primiparous women, the duration of the second stage of labour in the sitting position cohort was significantly shorter than that in the lithotomy position cohort (p < 0.00). There was no significant difference on the duration of the first stage of labour between the two cohorts (p = 0.455). A higher rate of spontaneous vaginal birth (p = 0.001) was observed among women in the sitting-birth cohort (93.4%, 85/91) than women in the lithotomy-birth cohort (75%, 69/92). For episiotomy, a significantly lower rate was found in the sitting-birth cohort, compared to the lithotomy-birth cohort (p = 0.001). Perineal injuries among non-episiotomy samples (in terms of complete and laceration) (p = 0.725) and postpartum 2 h-haemorrhage (p = 0.654) were not significantly different in the two cohorts. While among multiparous women, no statistical difference was found in all maternal outcomes between cohorts. None of the infants had an Apgar score of less than 7 at 1 min, 5 min or 10 min after birth, and the cord artery pH of all infants was higher than 7.0. Therefore, there were no cases of neonatal asphyxia in either the sitting position cohort or the lithotomy position cohort.

As shown in

Table 3, among primiparous women, the sitting position cohort reported significantly higher scores on the CEQ questionnaire (p < 0.001) across all four dimensions, including professional support (p = 0.000), self-ability (p = 0.000), self-perception (p = 0.000) and sense of participation (p = 0.000) compared to the lithotomy position cohort. For multiparous women, the CEQ scores did not differ significantly between the two cohorts (p = 0.074), except for the dimension of self-support (p = 0.019). (p = 0.019). Using the multivariate linear regression and the logistic regression analysis for primiparous women to adjust the potential impact of the confounders, including gestation weeks, age, BMI, weight gain, baby’s birth weight, oxytocin uses, epidural analgesia and low-risk complications, we gained the same results as above. We found that the sitting position has an independent impact in term of the duration of the second stage of labour, birth mode, episiotomy and the CEQ scores. The sitting-birth cohort showed a shorter duration of the second stage of labour(p < 0.01), more positive childbirth experience(p < 0.01), higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth(p < 0.01) and episiotomy(p < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference on the perineal injuries(p > 0.05) or postpartum 2h-haemorrhage (p > 0.05). The details are shown in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

In our study, we found that primiparous women who gave birth in sitting birth position had a shorter duration of the second stage of labour, which supported the results of the previous studies. Ganapathy et al. [

12] found a similar reduction of the duration in the second stage of labour in the sitting position group, compared to the lithotomy position group. In addition, a prior study conducted in China [

31] assigned 112 primiparous women into the sitting or the lithotomy position group during the second stage of labour, and reported that the duration of the second stage of labour was reduced by an average of 20 minutes in the sitting group, which were in line with our findings. Several possible explanations for the shortened duration of the second stage of labour in sitting position were proposed [

32,

33]. Firstly, the intensity of uterine contractions was stronger when women gave birth in a sitting position. Additionally, the sitting position could take advantage of the gravity and facilitate the descent of the fetal head; thereby shortening the duration of the second stage of labour. A prolonged second stage of labour may lead to adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes and other delivery complications, and thus it was necessary to take effective interventions to shorten the duration of the second stage of labour [

5]. Moreover, the available evidence also suggested the sitting position, which has the potential to promote the labour progression and decrease the adverse complications, as a preferable birth position option during the second stage of labour, especially for primiparous women [

25,

33].

In addition, our results suggested that the sitting position could promote spontaneous vaginal births and reduce episiotomies for primiparous women. Some studies also reported similar results, the findings indicated that women who adopted a sitting position were less likely to have instrumental birth and an episiotomy, and were more likely to have spontaneous vaginal births, which also lead to a lower perineal pain scores compared with women in the lithotomy position [

12,

17]. The findings from the current study indicated that the sitting position could potenrial enhance the natural progression of labour, minimize unnecessary interventions, lead to improved maternal outcomes, and also contribute to a great childbirth satisfaction among childbearing women. This also aligns with the ACOG committee’s recommendations that reducing unnecessary interventions during childbirth and promoting a more positive childbirth experience [

34]. Therefore, it is recommended that the sitting position may be a favourable birth position option during the second stage of labour for women. Additionally, regardless of parity, we did not find any significant difference in terms of the perineal injuries, postpartum 2h-haemorrhage, Apgar scores at 5 min and 10 min as well as the cord artery pH between the cohorts. It also indicated that the sitting position did not increase the risk of perineal injuries among multiparous women, which was consistent with the previous results [

10]. In general, the perineal injuries, as a common complication after vaginal birth, was associated with multiple negative maternal outcomes such as perineal pain, more blood loss during labour, pelvic floor injury and urinary incontinence [

23,

35]. However, the existing studies did not differentiate the effects of maternal positions on these outcomes; thus, more related research is warranted.

For the primiparas in our study, we found that women in the sitting position cohort reported a higher overall CEQ scores, which indicated a more positive childbirth experience in comparison to women in the lithotomy position. Further, based on the higher scores at all four dimensions of the CEQ for women who gave birth in the sitting position, the results showed that the sitting position could help women have a more satisfied professional support, gained the better self-ability, self-perception and the sense of participation. The results were similar to a prior study which aimed to compare the effects of maternal birthing experience in the sitting versus the lithotomy position during the second stage of labour [

12]. They found that women who adopted the sitting position reported a favorable birthing experience, as indicated by the lower intensity of labor pain measured by Visual Analogue Pain Scale. Thus, the fact that sitting position could reduce the women’s pain level may be a potential reason for a more positive childbirth experience. Another study also indicated that the freedom of movement and birth in the upright positions during the labour could increase the birth comfort of women, and result in a better experience [

16]. In recent years, the positive childbirth experience has become an essential indicator to assess the high-quality maternal care in the clinical practice [

36]. A positive childbirth experience can enhance women’s satisfaction of labour, promote neonatal growth and support postpartum recovery [

37]. However, the negative childbirth experience can lead to postpartum depression, fear of subsequent childbirth, and other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [

38]. Thus, it is necessary to adopt the effective interventions to improve the women’s childbirth experience. Based on our findings, it is recommended that women could assume the sitting position during the second stage of labour for a positive childbirth experience. Healthcare providers are also encouraged to consider the sitting position into present management of maternal positions in the clinical practice to improve the quality of maternal care.

4.1. Strengthens and limitations

Our study not only examined the effects of sitting position on maternal and neonatal outcomes, but also assessed the childbirth experience using a valid instrument, offering a comprehensive overview of the effects of sitting position during the second stage of labour. Given this, our results could provide a reference for both healthcare providers and women to choose the appropriate birth position during the second stage of labour for a positive childbirth experience and better maternal and neonatal outcomes, especially for primiparous women. There are also several limitations in our study. First, our findings were derived from a single-center study, which could potentially limit the generalization the results. Nevertheless, this study may facilitate improved planning for the future multicenter trials. Second, the sample of multiparous women is small, which may affect the reliability of results. Thus, we suggest that future studies with larger samples could be conducted. In addition, the childbirth experience was evaluated by questionnaire, lacking in-depth exploration of mothers’ perceptions regarding sitting positions. Consequently, there is a need for additional qualitative study or mixed-method studies in the future.

5. Conclusions

The results in our study indicated that primiparous women who gave birth in the sitting birth position in the second stage of labour had a shorter duration of the second stage of labour, higher rates of spontaneous vaginal births, fewer episiotomies and a more positive childbirth experience compared with those who assumed the lithotomy position. In addition, there was not any significance among the maternal and neonatal outcomes for multiparous women to adopt the sitting position in the second stage of labour. Thus, our findings provided an important reference for women to choose the sitting position in the second stage of labour for a positive childbirth experience. For healthcare providers, they could also give advice for women based on our findings, which could also provide an innovative value for clinical management of childbirth positions. We believed it will be also useful for healthcare providers to offer a high-quality maternal service for women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F., D.-X.L., H.-D.W. and T.W.; methodology, L.F., J.H., R.H. and H.L.; validation, L.F. and H.L.; formal analysis, L.F., J.H. and H.L.; investigation, D.-X.L., H.-D.W., L.-L.X. and T.W.; data curation, L.F., D.-X.L. and L.-L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.; writing—review and editing, L.F., J.H., R.H. and H.L.; visualization, L.F.; supervision, R.H. and H.L.; project administration, R.H. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing Natural Science Foundation, grant number 7222106.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study obtained ethical approval from the institutional review board (2022PHB188-001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Fu, W.; Pang, R.; et al. A Lancet Commission on 70 years of women’s reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in China. Lancet 2021, 397, 2497–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopas, M.L. A Review of Evidence-Based Practices for Management of the Second Stage of Labor. J. Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2014, 59, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Caughey, A.B. Defining and Managing Normal and Abnormal Second Stage of Labor. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2017, 44, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acog ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and Augmentation of Labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2003, 102, 1445–1454. [CrossRef]

- Pergialiotis, V.; Bellos, I.; Antsaklis, A.; Papapanagiotou, A.; Loutradis, D.; Daskalakis, G. Maternal and neonatal outcomes following a prolonged second stage of labor: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.K.; Sood, A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Vogel, J.P. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD002006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience [EB/OL].

- Zang, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhang, H.; Hou, R.; Lu, H. Practice Programme for Upright Positions in the Second Stage of Labour: The development of a complex intervention based on the Medical Research Council framework. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3608–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Lu, H. A literature review of application status of upright positions in the second stage of labour and prospects for future research. Chinese Nursing Management 2022, 22, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Elvander, C.; Ahlberg, M.; Thies-Lagergren, L.; Cnattingius, S.; Stephansson, O. Birth position and obstetric anal sphincter injury: a population-based study of 113 000 spontaneous births. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim-Hyppólito, S. Influence of the position of the mother at delivery over some maternal and neonatal outcomes. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1998, 63, S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagavathy, G.; Childbirth in Supported Sitting Maternal Position. International Journal of Nursing Education, 2012, Vol. 4, No. 2.

- Thies-Lagergren, L.; Kvist, L.J.; Sandin-Bojö, A.-K.; Christensson, K.; Hildingsson, I. Labour augmentation and fetal outcomes in relation to birth positions: A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluating birth seat births. Midwifery 2013, 29, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.Y.; Chen, L.H.; Zeng, L.L.; Ye, X.L. An analysis of the effect of the use of a birthing stool in conjunction with seated pushing for primiparous women in the second stage of labour. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 17, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, M.; Dakhesh, S.; Kalavani, L.; Valiani, M. A Comparative Study on the Effect of Using Three Maternal Positions on Postpartum Bleeding, Perineum Status and Some of the Birth Outcomes During Lathent and Active phase of the Second Stage of Labor. Cyprus J. Med Sci. 2021, 5, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacıvelioğlu, D.; Tavşanlı, N.G.; Şenyuva, I.; Kosova, F. Delivery in a vertical birth chair supported by freedom of movement during labor: A randomized control trial. Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.X.; Effect of modified semi-recumbent delivery on maternal and infant outcomes in the second stage of labor. Master’s degree, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2020.

- Turner, M.J.; Romney, M.L.; Webb, J.B.; Gordon, H. The birthing chair: an obstetric hazard? Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1986, 6, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies-Lagergren, L.; Kvist, L.J.; Christensson, K.; Hildingsson, I. No reduction in instrumental vaginal births and no increased risk for adverse perineal outcome in nulliparous women giving birth on a birth seat: results of a Swedish randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, L.A.; Ali Pour, F.R.; Shirazi, V. Effect of different birthing positions during the second stage of labor on mother’s experiences regarding birth, pain, anxiety and fatigue. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences 2012, 22, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 198: Prevention and Management of Obstetric Lacerations at Vaginal Delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018, 132, e87–e102. [CrossRef]

- Lipschuetz, M.; Cohen, S.M.; Lewkowicz, A.A.; Amsalem, H.; Haj Yahya, R.; Levitt, L.; Yagel, S.L. [PROLONGED SECOND STAGE OF LABOR: CAUSES AND OUTCOMES]. Harefuah 2018, 157, 685–690. [Google Scholar]

- Gimovsky, A.C.; Berghella, V. Evidence-based labor management: second stage of labor (part 4). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 4, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, L.; Pang, R. Adaptation of the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) in China: A multisite cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0215373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dencker, A.; Taft, C.; Bergqvist, L.; Lilja, H.; Berg, M. Childbirth experience questionnaire (CEQ): development and evaluation of a multidimensional instrument. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.P. The methods of sample size estimation in clinical study. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2003, 1569–157. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, A.O.; Flores Romero, A.L.; Morales García, V.E. [Comparison of obstetric and perinatal results of childbirth vertical position vs. childbirth supine position]. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2013, 81, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. IBM Corp; 2020.

- Liu, S.S.; Shen, L.L.; Tu, L.; Lu, L.H. A study of the effects of semi-sedentary labour in the second stage of labour. Electronic Journal of Practical Clinical Nursing Science 2018, 3, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Desseauve, D.; Fradet, L.; Lacouture, P.; Pierre, F. Position for labor and birth: State of knowledge and biomechanical perspectives. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 208, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Zang, Y.; Ren, L.-H.; Li, F.-J.; Lu, H. A review and comparison of common maternal positions during the second-stage of labor. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee Opinion, No. 766: Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2019, 133, e164–e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.J.; Sadler, K.; Leli, K. Obstetric Lacerations: Prevention and Repair. 2021, 103, 745–752.

- Donate-Manzanares, M.; Rodríguez-Cano, T.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Santos-Hernández, G.; Beato-Fernández, L. Mixed-method study of women’s assessment and experience of childbirth care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4195–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari-Homaie, S.; Meedya, S.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Mohammadi, E.; Mirghafourvand, M. Recommendations for improving primiparous women’s childbirth experience: results from a multiphase study in Iran. Reprod. Heal. 2021, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coo, S.; García, M.I.; Mira, A. Examining the association between subjective childbirth experience and maternal mental health at six months postpartum. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2021, 41, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joensuu, J.M.; Joensuu, J.M.; Saarijärvi, H.; Saarijärvi, H.; Rouhe, H.; Rouhe, H.; Gissler, M.; Gissler, M.; Ulander, V.-M.; Ulander, V.-M.; et al. Effect of the maternal childbirth experience on a subsequent birth: a retrospective 7-year cohort study of primiparas in Finland. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).