Submitted:

28 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

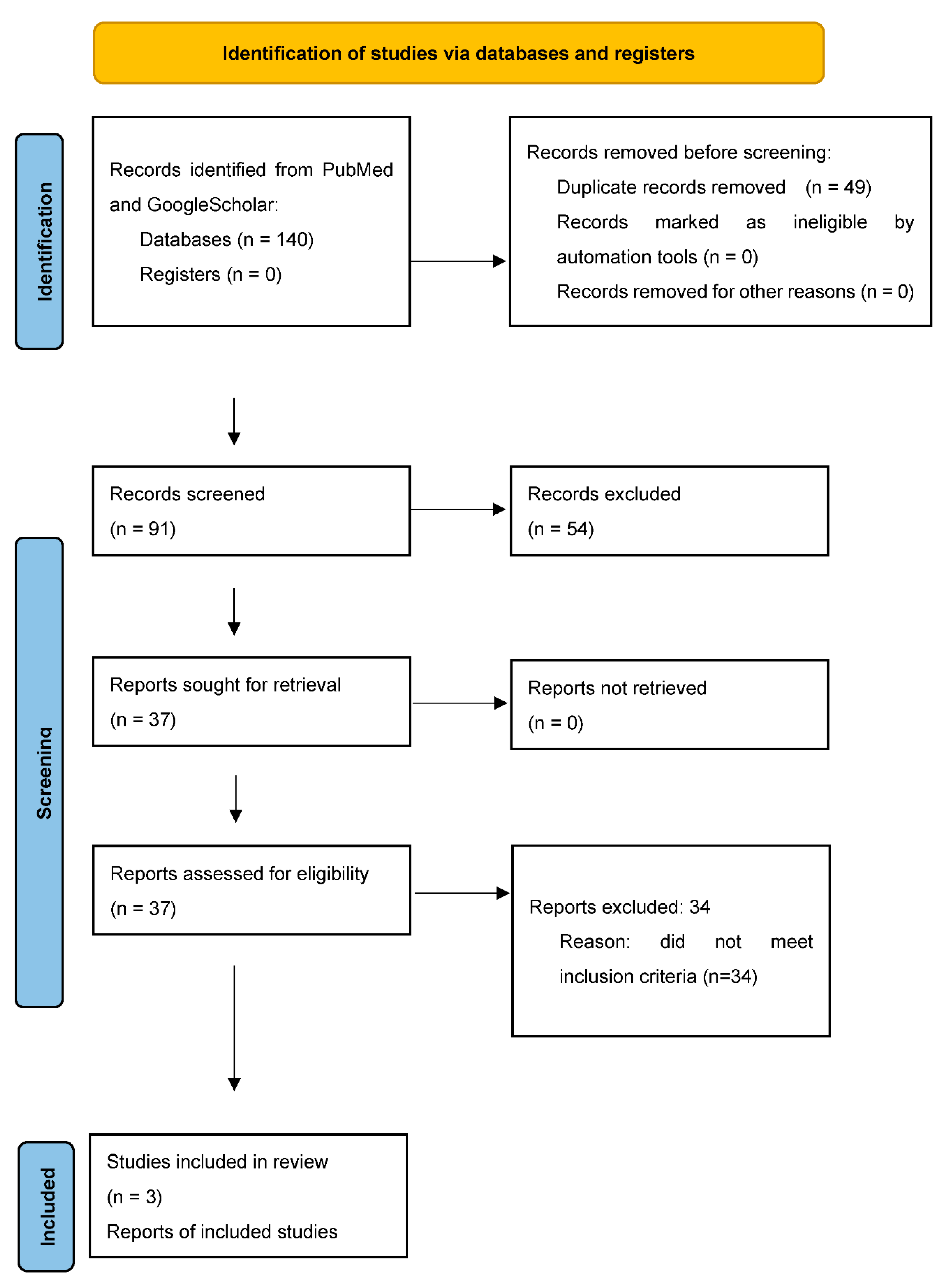

2. Materials and methods

Search strategy

Selection process and criteria

Inclusion criteria

Data extraction and synthesis

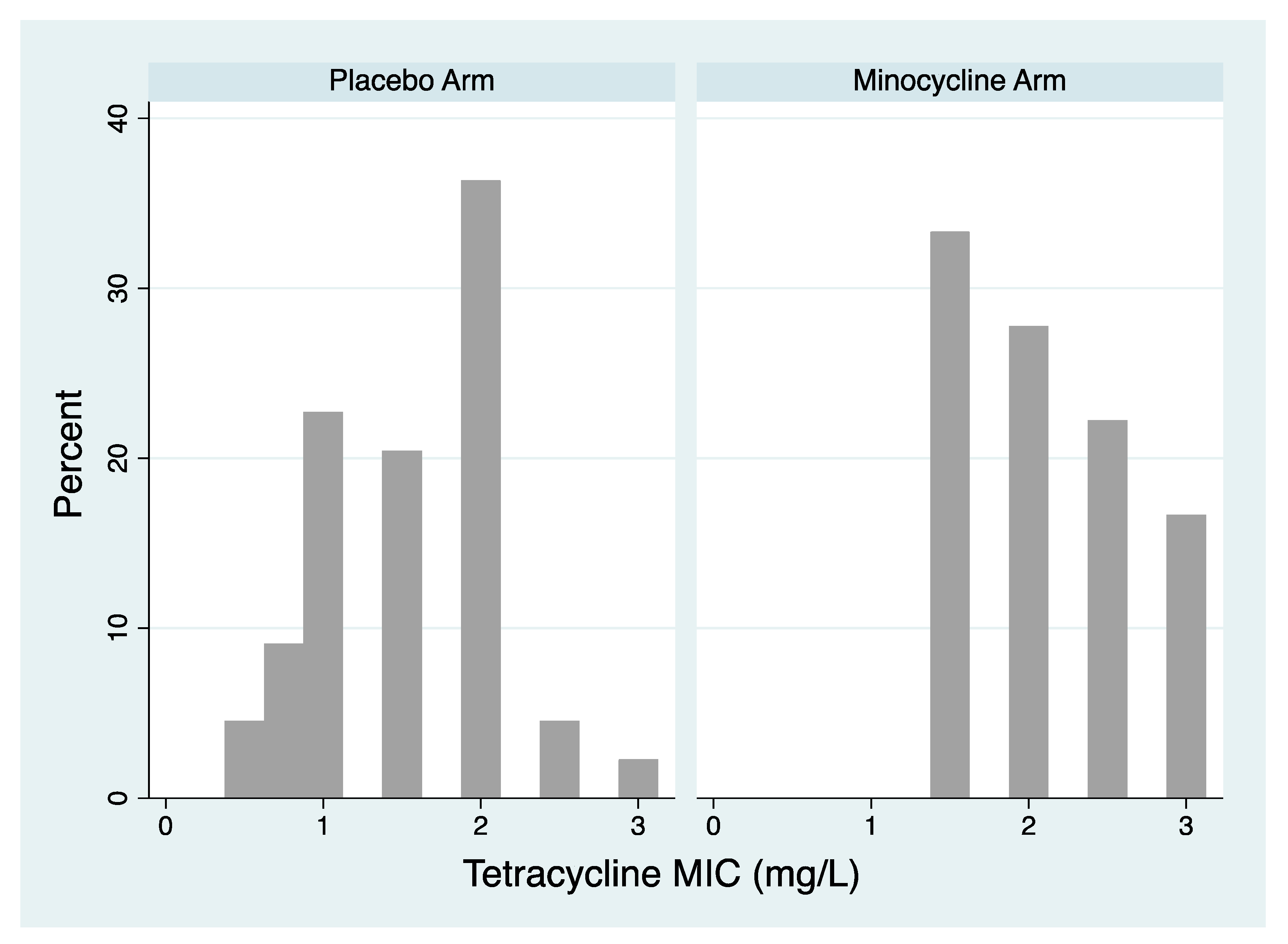

- Tetracycline MIC distribution of isolates. The tetracycline MIC distribution of isolates per species of the two arms post PEP were compared with the Mann-Whitney test.

- The proportion of isolates resistant to tetracycline. This variable was calculated for each bacterial species as the number of individuals with tetracycline resistant isolates cultured per total number of individuals with this same species cultured. If only MIC distribution was available, we calculated the proportion of tetracycline resistance using the resistance thresholds used in the other studies included this review, in order to allow for comparison (≥ 1 or 2 mg/L). The number of events and the number of participants included in the control and intervention groups of each study were extracted. Data was extracted for all bacterial species with available data.

- Tetracycline MIC distribution of isolates. This data was only available for N. gonorrhoeae from a single study. The tetracycline MIC distribution of gonococcal isolates per species of the two arms for the tetracycline and placebo groups post PEP were compared with the Mann-Whitney test.

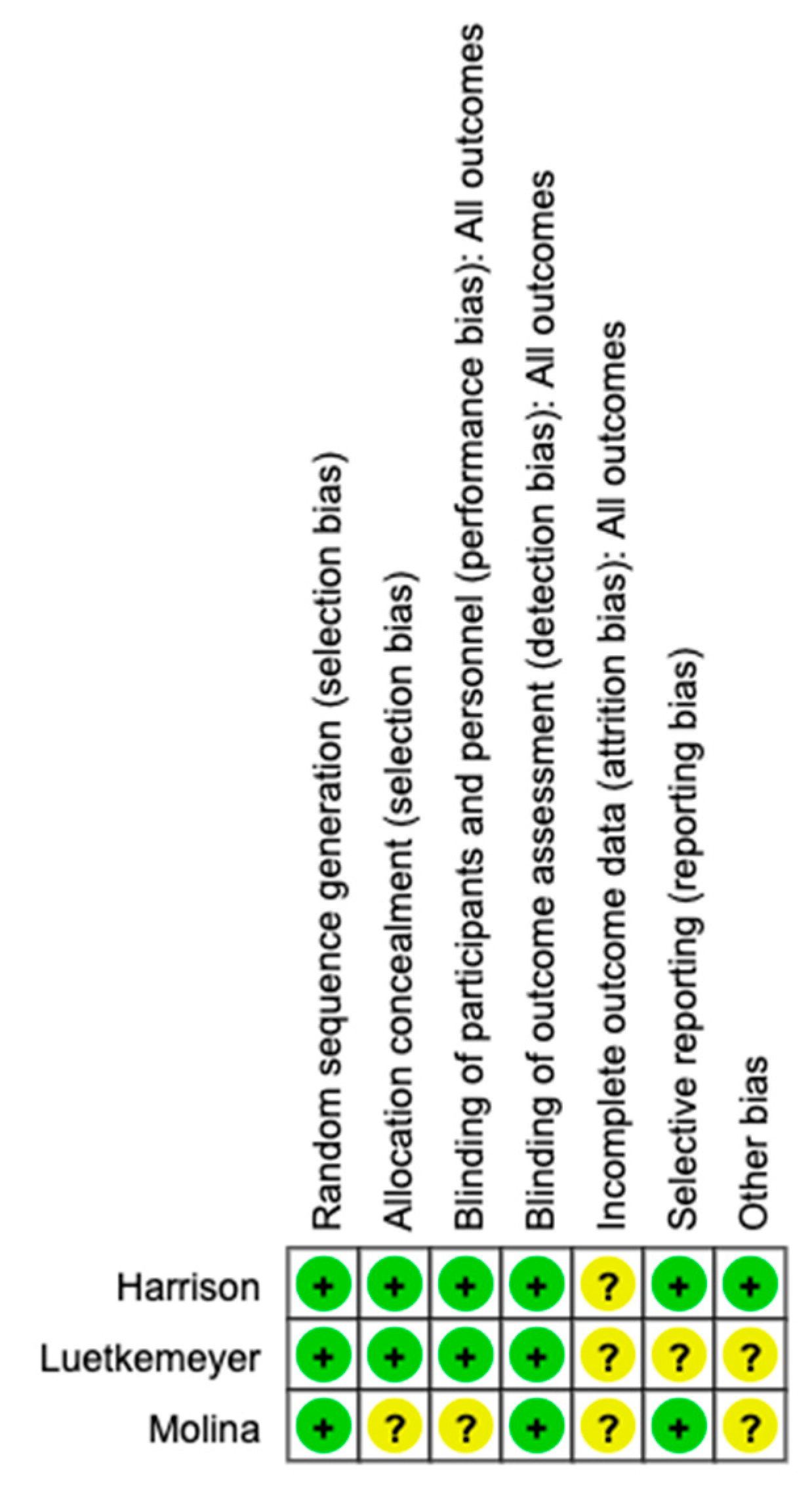

Risk of bias assessment

3. Results

Study characteristics

Assessment of risk of bias

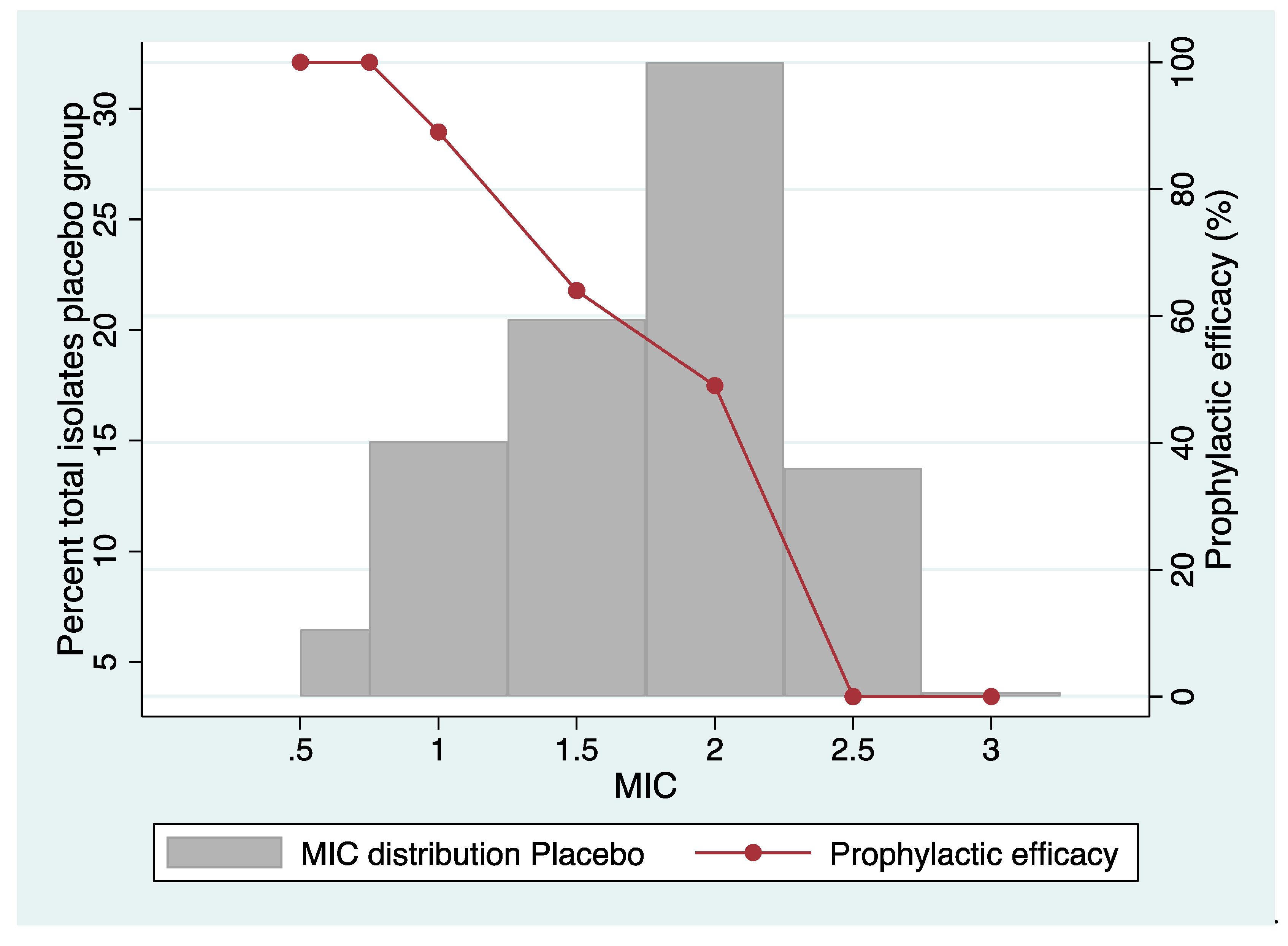

Tetracycline resistance in N. gonorrhoeae

- Proportion resistant

- Effect on MIC distribution

Tetracycline resistance in commensal Neisseria species

Tetracycline resistance in Staphylococccus aureus

Tetracycline resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Consent for publication

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molina, J.-M.; Charreau, I.; Chidiac, C.; Pialoux, G.; Cua, E.; Delaugerre, C.; Capitant, C.; Rojas-Castro, D.; Fonsart, J.; Bercot, B.; et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 308–317. [CrossRef]

- Bolan RK, Beymer MR, Weiss RE, et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis to reduce incident syphilis among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who continue to engage in high risk sex: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2015;42(2):98. [CrossRef]

- Luetkemeyer, A.F.; Donnell, D.; Dombrowski, J.C.; Cohen, S.; Grabow, C.; Brown, C.E.; Malinski, C.; Perkins, R.; Nasser, M.; Lopez, C.; et al. Postexposure Doxycycline to Prevent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1296–1306. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Michel Molina BB, Lambert Assoumou, Algarte-Genin Michele, et al,. ANRS 174 DOXYVAC: an open-label randomized trial to prevent STIs in MSM on PrEP. CROI 2023, Seattle, Washington.

- Kong, F.Y.S.; Kenyon, C.; Unemo, M. Important considerations regarding the widespread use of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis against sexually transmitted infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1561–1568. [CrossRef]

- Luetkemeyer AF, Donnell D, Dombrowski JC, et al. DoxyPEP and antimicrobial resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, commensal Neisseria and S. aureus. CROI 2023, Seattle, Washington.

- Population Health Division San Francisco Department of Health. Doxycycline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Reduces Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2022.

- Stewart J, Bukusi E, Sesay FA, et al. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis for prevention of stis among cisgender women. CROI 2023, Seattle, Washington. 2022;23(1):495. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, W.O.; Hooper, R.R.; Wiesner, P.J.; Campbell, A.F.; Karney, W.W.; Reynolds, G.H.; Jones, O.G.; Holmes, K.K. A Trial of Minocycline Given after Exposure to Prevent Gonorrhea. New Engl. J. Med. 1979, 300, 1074–1078. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88. [CrossRef]

- Torgerson DJ. Contamination in trials: is cluster randomisation the answer? Bmj. 2001;322(7282):355-7. [CrossRef]

- Berçot, B.; Charreau, I.; Rousseau, C.; Delaugerre, C.; Chidiac, C.; Pialoux, G.; Capitant, C.; Bourgeois-Nicolaos, N.; Raffi, F.; Pereyre, S.; et al. High Prevalence and High Rate of Antibiotic Resistance of Mycoplasma genitalium Infections in Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e2127–e2133. [CrossRef]

- Fedorov V, Mannino F, Zhang R. Consequences of dichotomization. Pharmaceutical Statistics: The Journal of Applied Statistics in the Pharmaceutical Industry. 2009;8(1):50-61. [CrossRef]

- Eagle, H.; Gude, A.V.; Beckmann, G.E.; Mast, G.; Sapero, J.J.; Shindledecker, J.B. PREVENTION OF GONORRHEA WITH PENICILLIN TABLETS. JAMA 1949, 140, 940–3. [CrossRef]

- Loveless JA, Denton W. The oral use of sulfathiazole as a prophylaxis for gonorrhea Journal of the American Medical Association. 1943;121(11):827-8. [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, C.; Laumen, J.; Van Dijck, C. Could Intensive Screening for Gonorrhea/Chlamydia in Preexposure Prophylaxis Cohorts Select for Resistance? Historical Lessons From a Mass Treatment Campaign in Greenland. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 47, 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Millar, J.W.; Siess, E.E.; Feldman, H.A.; Silverman, C.; Frank, P. In Vivo and In Vitro Resistance to Sulfadiazine in Strains of Neisseria Meningitidis. JAMA 1963, 186, 139–141. [CrossRef]

- DA S, DC K, Sack R. Prophylactic doxycycline for travelers diarrhea. Results of a prospective double-blind study of Peace Corps volunteers in Kenya. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:758-63. [CrossRef]

- Sack, R.B.; Santosham, M.; Froehlich, J.L.; Medina, C.; Orskov, F.; Orskov, I. Doxycycline Prophylaxis of Travelers' Diarrhea in Honduras, an Area where Resistance to Doxycycline is Common among Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli *. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1984, 33, 460–466. [CrossRef]

- Kantele, A.; Laaveri, T.; Mero, S.; Vilkman, K.; Pakkanen, S.H.; Ollgren, J.; Antikainen, J.; Kirveskari, J. Antimicrobials Increase Travelers' Risk of Colonization by Extended-Spectrum Betalactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 837–846. [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M.S.; Connor, B.A.; Beeching, N.J.; DuPont, H.L.; Hamer, D.H.; Kozarsky, P.; Libman, M.; Steffen, R.; Taylor, D.; Tribble, D.R.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, S63–S80. [CrossRef]

- Sanders CC, Sanders Jr WE, Goering RV, et al. Selection of multiple antibiotic resistance by quinolones, beta-lactams, and aminoglycosides with special reference to cross-resistance between unrelated drug classes. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1984;26(6):797-801. [CrossRef]

- Tedijanto, C.; Olesen, S.W.; Grad, Y.H.; Lipsitch, M. Estimating the proportion of bystander selection for antibiotic resistance among potentially pathogenic bacterial flora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 201810840–E11995. [CrossRef]

- Vanbaelen T, Manoharan-Basil SS, Kenyon C. Doxycycline Post Exposure Prophylaxis could induce cross-resistance to other classes of antimicrobials in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: an in-silico analysis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2023.

- Kenyon, C.R.; Schwartz, I.S. Effects of Sexual Network Connectivity and Antimicrobial Drug Use on Antimicrobial Resistance inNeisseria gonorrhoeae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1195–1203. [CrossRef]

- Lipsitch, M.; Samore, M.H. Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Population Perspective. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 347–354. [CrossRef]

- Truong, R.; Tang, V.; Grennan, T.; Tan, D.H.S. A systematic review of the impacts of oral tetracycline class antibiotics on antimicrobial resistance in normal human flora. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022, 4, dlac009. [CrossRef]

| Study, Year of publication, references | Target bacterial species assessed for tetracycline susceptibility | Country | Study Population/method | PEP protocol | MIC testing methodology | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrison 1979 (9) |

N. gonorrhoeae | USA | 1080 men from a US Navy ship after sexual exposure during 2 periods of leave in a port in East Asia randomized to either 200mg minocycline or placebo after each sexual exposure, but maximum 200mg per 18 hour period. 815 of these men were reinterviewed and had urethral samples taken at a single time point. MIC results available for 62 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae out of 81 incident N. gonorrhoeae infections. | 200mg minocycline after each sexual exposure (median time between sex and PEP 8 hours, range 30min-36 hours) | Agar dilution with tetracycline. MICs of each isolate reported. Threshold for definition of tetracycline resistance not defined |

Overall, 54% reduction in culture positive urethral gonorrhoea. No effect on infections with elevated minocycline MIC |

| Molina 2018 (1, 12) |

N. gonorrhoeae, M. genitalium | France | 232 MSM randomized 1:1 to doxycycline (200mg) or no prophylaxis within 24 hours post each episode of condomless sex. Follow up was 10 months. NG tested for via quarterly NG PCR of the pharynx/rectum/urine. Primary analysis mITT. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a first STI, defined as first episode of syphilis, chlamydia, or gonorrhoea infection. MIC results were provided for 9 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae out of 57 incident N. gonorrhoeae infections. Culture was only attempted in 28 of the infections. | 200mg doxycycline within 24 hours after condomless sex | Agar dilution with tetracycline. Resistance defined as ≥1mg/L. Only proportion of resistant isolates were reported (MICs of each isolate were not reported) | Occurrence of a first STI was lower in the doxyPEP arm than in the placebo arm (HR 0.53). Doxycycline reduced the occurrence of a first episode of chlamydia (HR 0.3) and syphilis (HR 0.27). The effect on gonorrhoea was not significant. |

| Luetkemeyer 2023 (3, 6) | N. gonorrhoeae, commensal Neisseria species, S. aureus | USA | 501 MSM and transgender women (327 in the PrEP cohort and 174 in the PLWH cohort), with a history of chlamydia, gonorrhoea or syphilis in the past 12 months were randomized 2:1 to doxycycline (200mg) or placebo within 72 hours post each episode of condomless sex. Followed up quarterly for 12 months. NG tested for via quarterly NG PCR of the pharynx/rectum/urine. The primary analysis was mITT. The primary outcome was the incidence of at least one bacterial STI (gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis) each quarter. cumulative incidence of each STI over 12 months. Tetracycline susceptibility data available for 29 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae out of 157 incident N. gonorrhoeae infections, for 162 isolates of S. Aureus and for 178 isolates of commensal Neisseria spp. | 200mg doxycycline within 72 hours after condomless sex | Agar dilution with tetracycline. Resistance defined as ≥2mg/L. Only proportion of resistant isolates were reported (MICs of each isolate were not reported) | Doxycycline reduced the incidence of at least one diagnosed STI (RR 0.34 in PrEP cohort and 0.38 PLWHIV), of gonorrhoea (RR 4.5/0.43 respectively), chlamydia (RR 0.12/0.26, respectively) and syphilis (0.13/0.23, respectively) |

| Study, Year of publication | Target bacterial species | Tetracycline breakpoint (mg/L) |

Baseline | Month 12 (During follow up for N. gonorrhoeae) | ||

| Tetracycline arm N resistant/N tested (% resistant to tetracycline) | Placebo arm N resistant/N tested (% resistant to tetracycline) | Tetracycline arm N resistant/N tested (% resistant to tetracycline) | Placebo arm N resistant/N tested (% resistant to tetracycline) | |||

| Harrison 1979 | N. gonorrhoeae | ≥1mg/L | NA | NA | 18/18 (100%) | 38/44 (86.4%) |

| Harrison 1979 | N. gonorrhoeae | ≥2mg/L | NA | NA | 12/18 (66.7%) | 19/44 (43.2%) |

| Molina 2018 | N. gonorrhoeae | ≥1mg/L | NA | NA | 0/2 (0%) | 4/6 (66.7%) |

| Luetkemeyer 2023 | N. gonorrhoeae | ≥2mg/L | 2/7 (28.6%) | 2/8 (25%) | 5/13 (38.5%) | 2/16 (12.5%) |

| Commensal Neisseria spp. | ≥2mg/L | 189/302 (62.6%) | 92/153 (60.1%) | 85/122 (69.7%) | 25/56 (44.6%)* | |

| S. aureus | ≥2mg/L | 12/334 (3.6%) | 19/161 (11.8%) | 16/137 (11.7%) | 3/62 (4.8%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).