Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model development

2.1. Definition of indicators

2.2. Decomposition by LMDI method

| Item | Definition |

|---|---|

| Annual changes in total operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) | |

| Annual contribution from population changes in Japan to the operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) | |

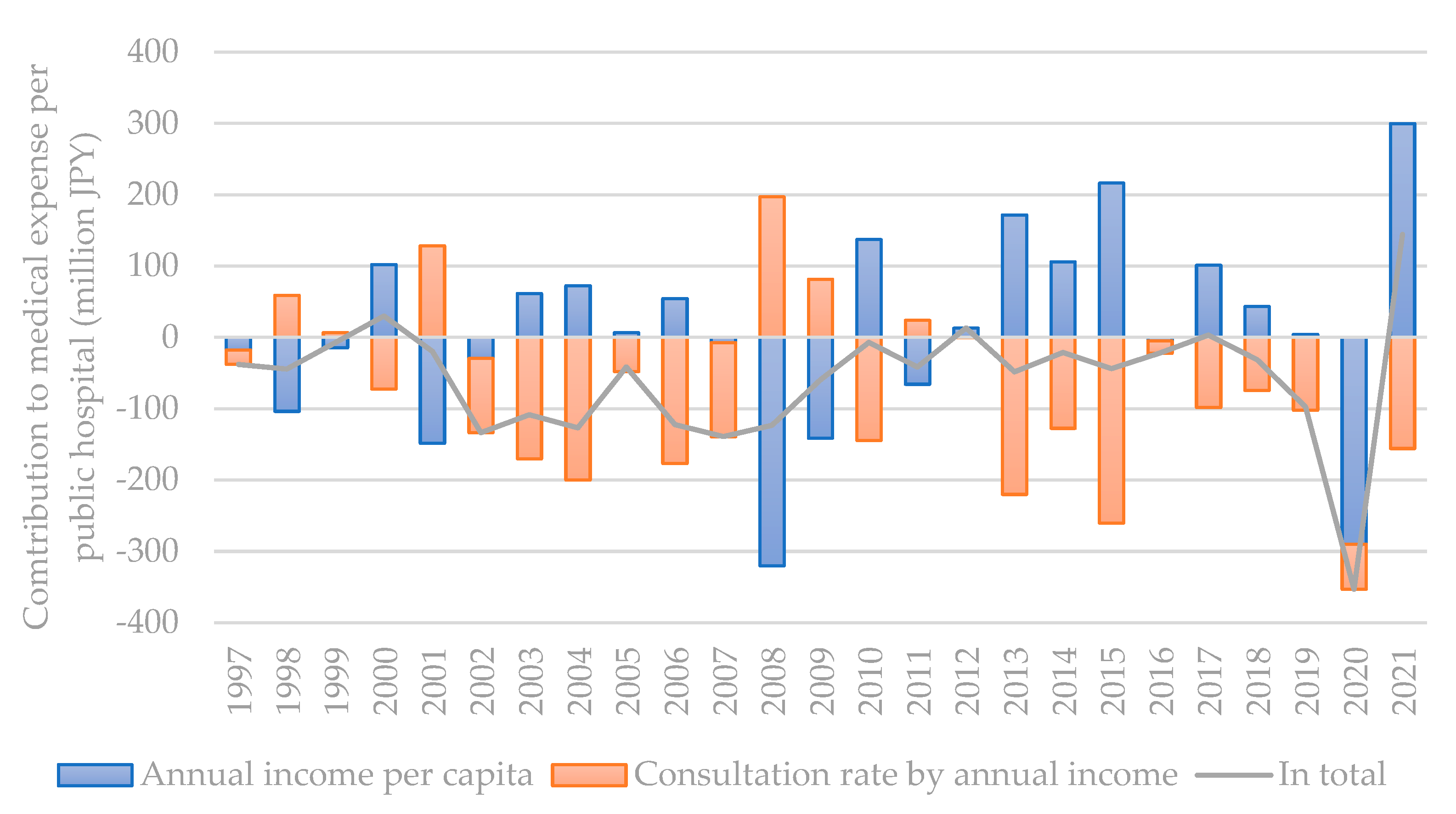

| Annual contribution from income level changes to the operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) | |

| Annual contribution from consultation rate changes to the operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) | |

| Annual contribution from the changes in patient visit duration to the operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) | |

| Annual contribution from the structural changes and cost-efficiency management level to the operating cost of one public hospital (JPY) |

2.3. Data preparation

3. Results and discussion

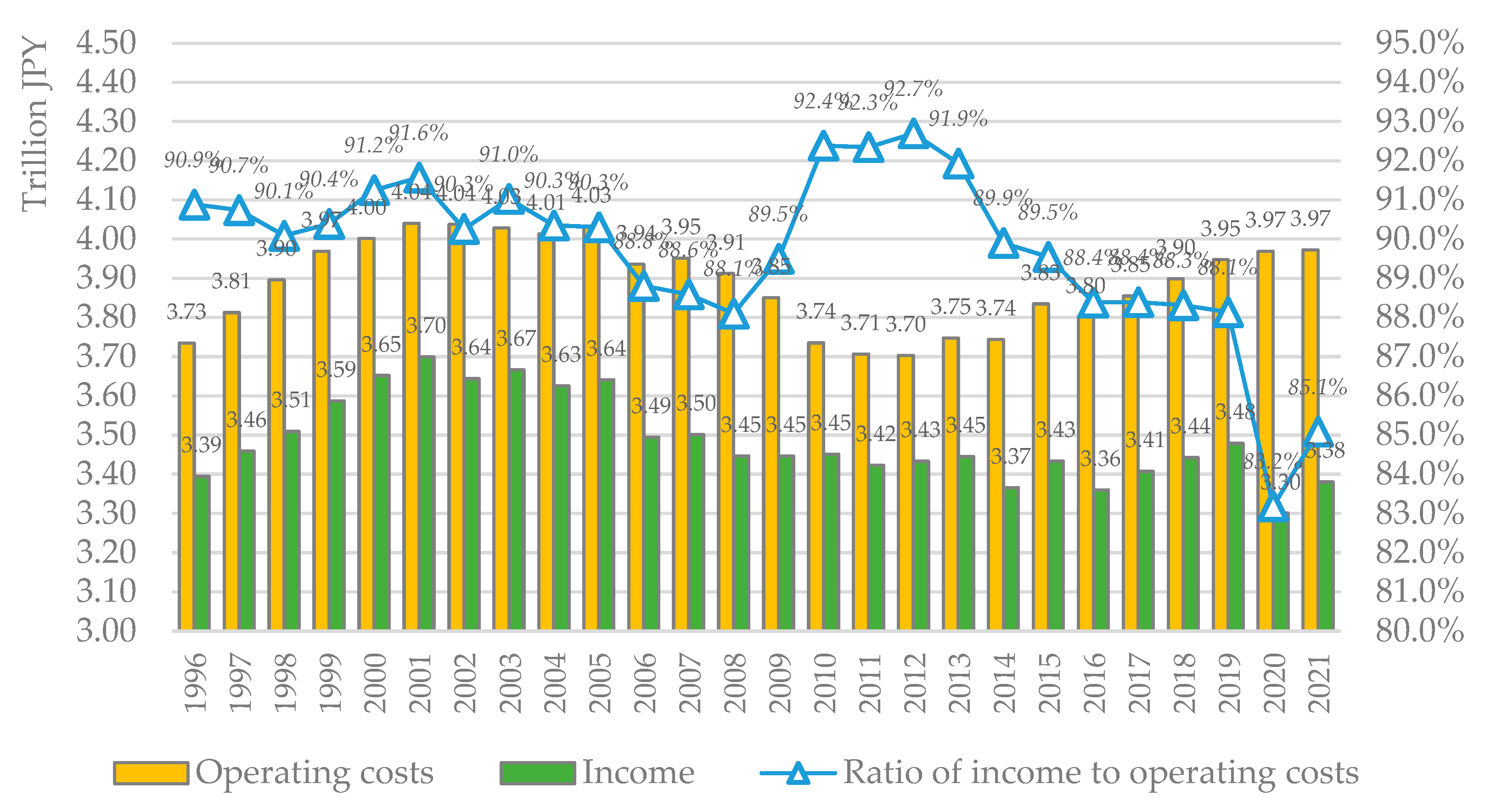

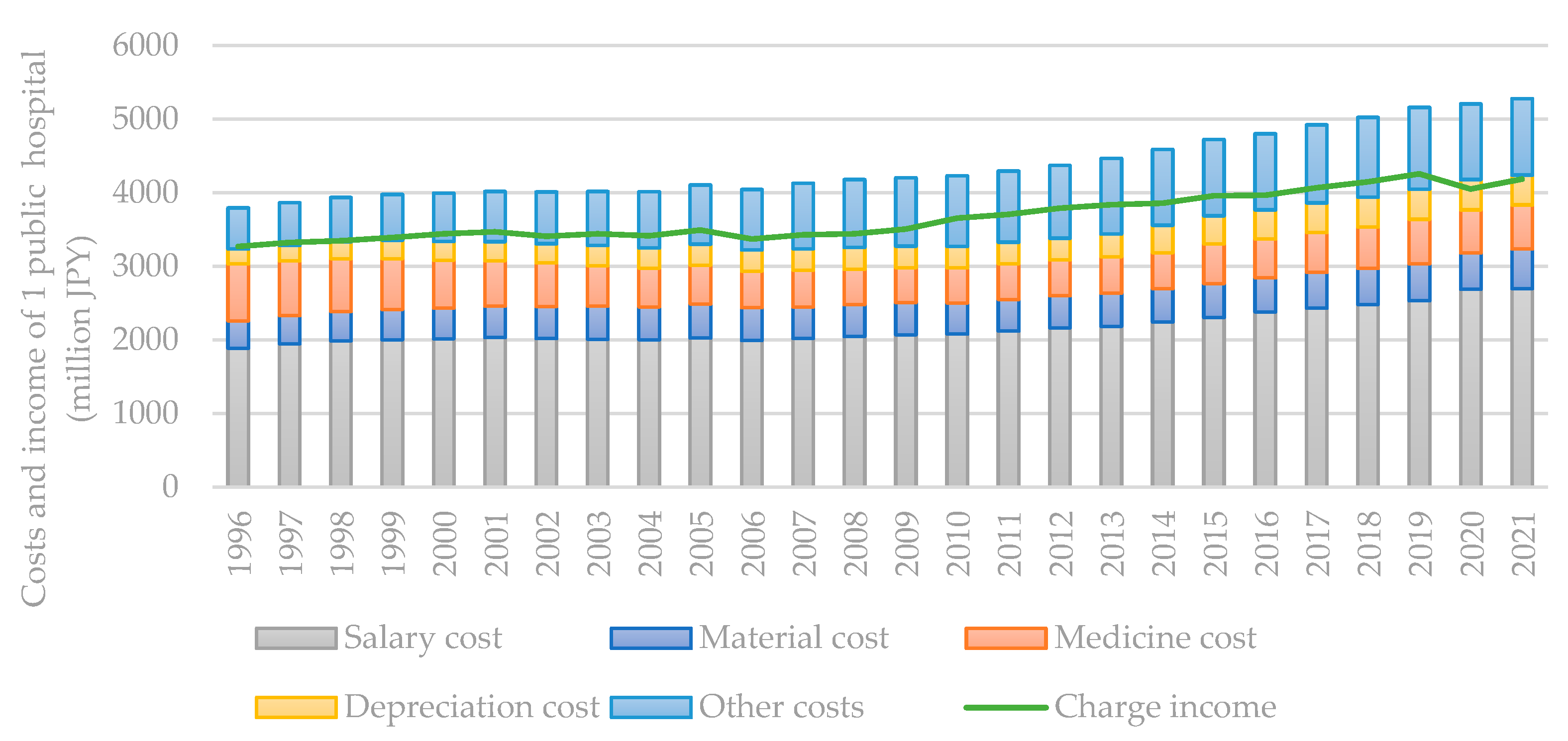

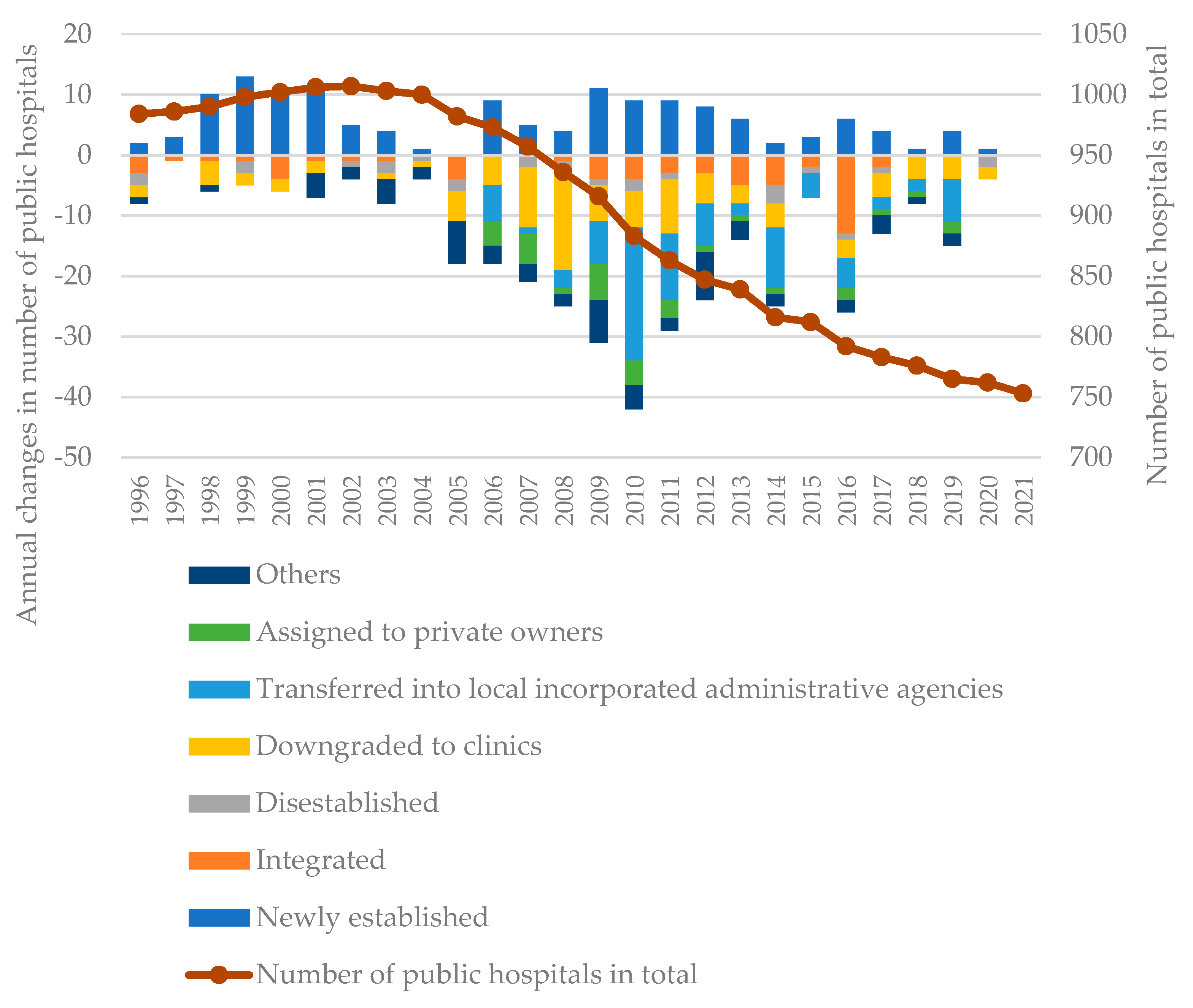

3.1. Historical changes in influencing factors

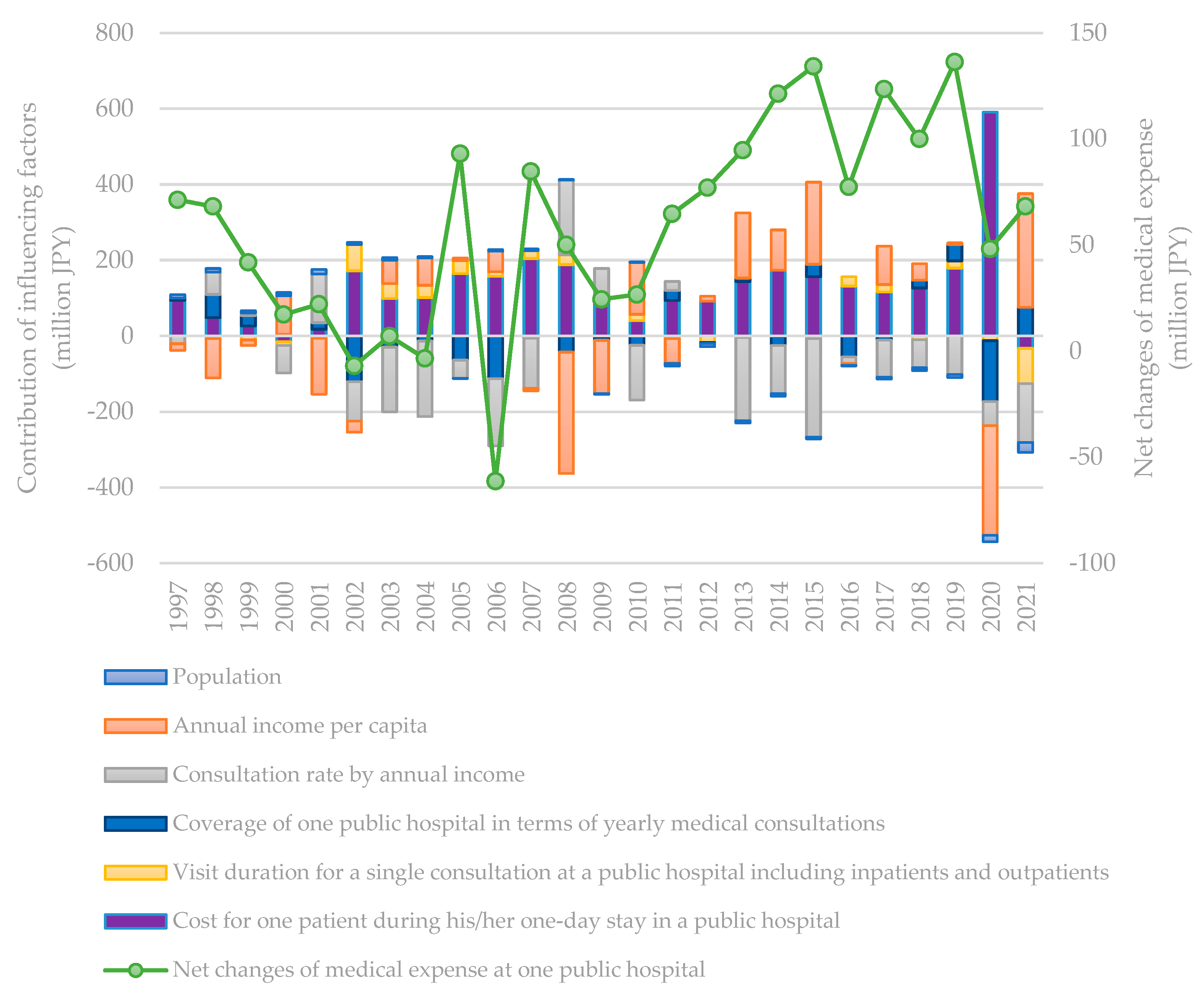

3.2. Contribution of influencing factors based on decomposition results

3.3. Discussion

- Impact from the institutional integration of public hospitals

- 2.

- Impact of a decreasing population and an ageing society

- 3.

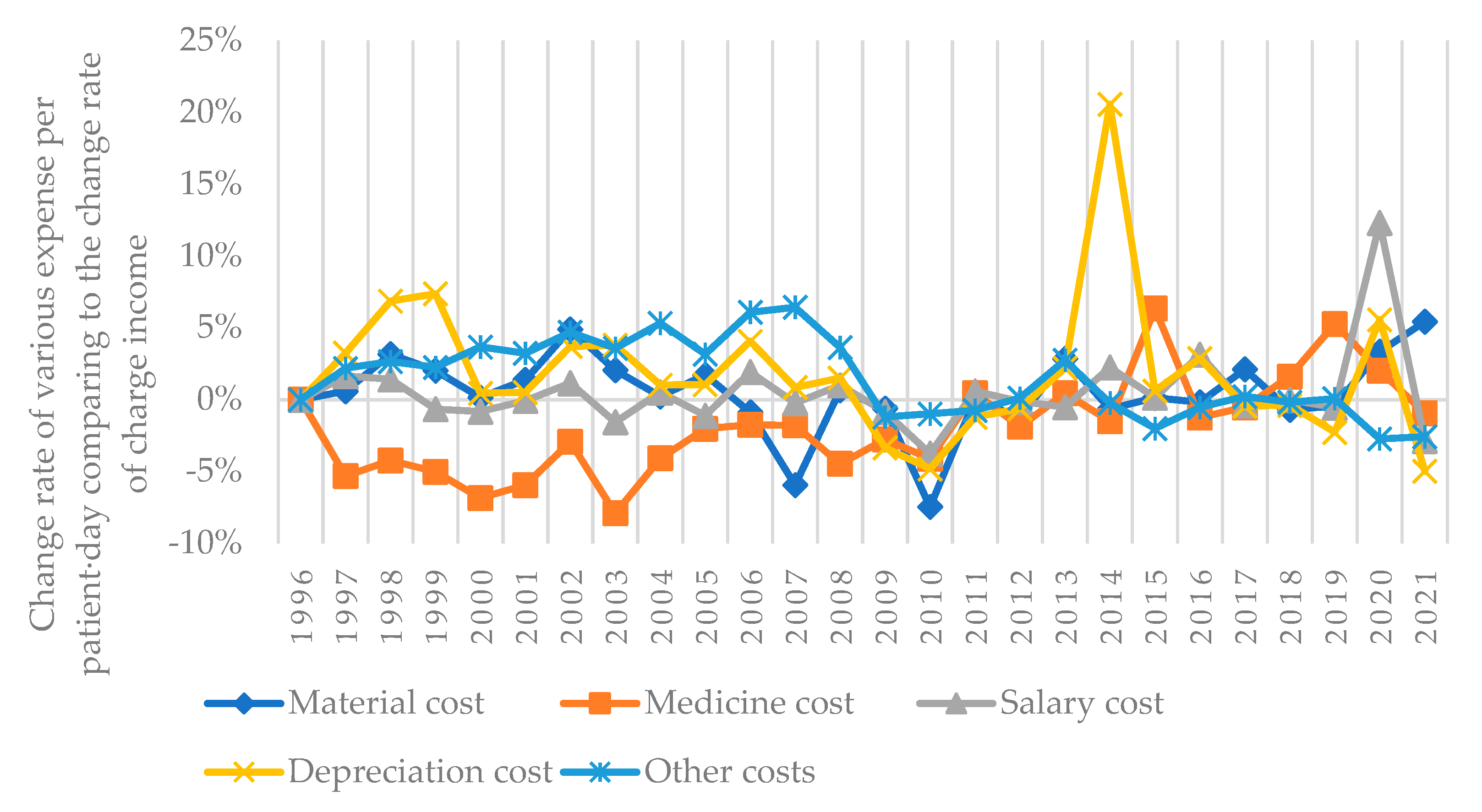

- Operating cost level changes compared with charge income level

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, Y. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a tertiary care public hospital in Singapore: resources and economic costs. J Hosp Infect 121, 1-8 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Q., Cai, M., Li, Z. P., Lin, X. J. & Wang, L. A. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Hospitals of Different Levels: Six-Month Evidence from Shanghai, China. Risk Manag Healthc P 14, 3635-3651 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Barber, S. L., Borowitz, M., Bekedam, H. & Ma, J. The hospital of the future in China: China's reform of public hospitals and trends from industrialized countries. Health Policy Plann 29, 367-378 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Fidler, A. H., Haslinger, R. R., Hofmarcher, M. M., Jesse, M. & Palu, T. Incorporation of public hospitals: A "silver bullet" against overcapacity, managerial bottlenecks and resource constraints? Case studies from Austria and Estonia. Health Policy 81, 328-338 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Besstremyannaya, G. The Impact of Japanese Hospital Financing Reform on Hospital Efficiency: A Difference-in-Difference Approach. Jpn Econ Rev 64, 337-362 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Han, A., Lee, K. H. & Park, J. The impact of price transparency and competition on hospital costs: a research on all-payer claims databases. Bmc Health Serv Res 22 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. C., Gong, X., Yao, Q. H. & Liu, Q. Impacts of the medical arms race on medical expenses: a public hospital-based study in Shenzhen, China, during 2009-2013. Cost Effect Resour A 20 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ramamonjiarivelo, Z. et al. Public hospitals in financial distress: Is privatization a strategic choice? Health Care Manage R 40, 337-347 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D. J. & Link, C. R. Better outcomes at lower costs? The effect of public health expenditures on hospital efficiency. Appl Econ 52, 400-414 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadakis, G., Doumpos, M., Zopounidis, C. & Germain, C. Operational and economic efficiency analysis of public hospitals in Greece. Ann Oper Res 247, 787-806 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, H., Tone, K. & Tsutsui, M. Estimation of the efficiency of Japanese hospitals using a dynamic and network data envelopment analysis model. Health Care Manag Sc 17, 101-112 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. L., Jia, M. Y., Lin, Q., Zhu, J. W. & Wang, D. Effects of Chinese medical pricing reform on the structure of hospital revenue and healthcare expenditure in county hospital: an interrupted time series analysis. Bmc Health Serv Res 21 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, H. et al. Japan: Universal Health Care at 50 years 3 Cost containment and quality of care in Japan: is there a trade-off? Lancet 378, 1174-1182 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Iseki, T. Recent Municipal Hospital Policy Transition and Municipal Hospital Reform Guidelines (in Japanese). Journal of Social Security Research 1, 778-796 (2017).

- .

- Taniguchi, K., Nozawa, R., Koike, D., Ninomiya, T. & Ueda, S. Risk factors analysis of hospital management which points to extract part system. Kawasaki Journal of Medical Welfare 14, 109-123 (2004).

- Shimomura, K. & Kubo, R. Quantitative Analysis of Cost Structures in Hospital Management --Comparison between groups of surplus and deficit hospitals belonging to the National Hospital Organization--. Journal of the Japan Society for Healthcare Administration 48, 129-136 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M. Factor Analyses Regarding Transition in Hospital Profit Before and After Public Hospital Reform at Public Hospitals Mainly Providing Acute Medical Services. Journal of Japanese Association for Health Care Administrators 13, 11-17 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K. Factors influencing the optimization of management in the public hospital reform plan─Focusing on hospitals directly managed by local governments. Journal of the Japan Society for Healthcare Administration 53, 7-18 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, T. & Imanaka, Y. Determinants of change in the revenue to cost ratio of municipal hospitals by scale in Japan. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi(JAPANESE JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH) 55, 761-767 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, H. Study for Development of a Benchmarking Method in Hospital Management Using a Multivariate Statistical Technique subtitle_in_Japanese. Iryo To Shakai 15, 2_23-22_37 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. & Guo, F. Y. Analysis of rural residential commercial energy consumption in China. Energy 52, 222-229 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P. F., Landajo, M. & Presno, M. J. Multilevel LMDI decomposition of changes in aggregate energy consumption. A cross country analysis in the EU-27. Energ Policy 68, 576-584 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Goh, T. & Ang, B. W. Tracking economy-wide energy efficiency using LMDI: approach and practices. Energ Effic 12, 829-847 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. C., He, Z. X. & Long, R. Y. Factors that influence carbon emissions due to energy consumption in China: Decomposition analysis using LMDI. Appl Energ 127, 182-193 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. et al. Regional disparity analysis of Chinese freight transport CO2 emissions from 1990 to 2007: Driving forces and policy challenges. J Transp Geogr 56, 1-14 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. & Kong, Q. Y. Analysis on the influencing factors of carbon emissions from energy consumption in China based on LMDI method. Nat Hazards 88, 1691-1707 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, V., Moreira, A. C. & Silva, P. M. The driving forces of change in energy-related CO2 emissions in Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern Europe: The LMDI approach to decomposition analysis. Renew Sust Energ Rev 50, 1485-1499 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Li, H. A., Zhou, M. & Mu, H. L. Decomposition analysis of energy consumption in Chinese transportation sector. Appl Energ 88, 2279-2285 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. et al. Factor decomposition analysis and causal mechanism investigation on urban transport CO2 emissions: Comparative study on Shanghai and Tokyo. Energ Policy 107, 658-668 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ang, B. W. The LMDI approach to decomposition analysis: a practical guide. Energ Policy 33, 867-871 (2005). [CrossRef]

- MHLWJ. Survey of Medical Institutions. (The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (MHLWJ), Tokyo, Japan, 1996-2021).

- MOF. Trade Statistics of Japan. (Ministry of Finance (MOF), Tokyo, Japan, 2022).

| Studies | Analysis tools | Identified key influencing factors |

| Ishikawa, 2019 | Multivariate regression analysis | Number of outpatients and average stay duration of inpatients contribute to operating profit, material cost and salary cost contribute to operating deficit |

| Ishibashi, 2016 | Multivariate regression analysis | Charge income from inpatients, number of inpatients per day, and charge income from outpatients contribute to operating profit, retirement bonus and depreciation cost contribute to operating deficit |

| Shimomura and Kubo, 2011 | t-test analysis | Insurance appraisal, salary cost, material cost, medical consumables cost, equipment-related cost, depreciation cost, etc. |

| Otsubo and Imanaka, 2008 | Multivariate multiple regression analysis | Number of outpatients and charge income from outpatients per person·day contribute to operating profit, depreciation cost contributes to operating deficit |

| Kawaguchi, 2005 | Cluster analysis | Ratio of salary cost and material cost to the total operating costs is the main factor influencing operating efficiency |

| Taniguchi et al., 2004 | Risk factor analysis | Salary cost, charge income from outpatients, material cost, depreciation cost, etc. |

| Item | Definition |

|---|---|

| Average total operating costs of one public hospital in Japan in year t (JPY) | |

| Population of Japan in year t (person) | |

| Annual income per capita in year t (JPY/person) | |

| Consultation rate by annual income in the year t (times/JPY) | |

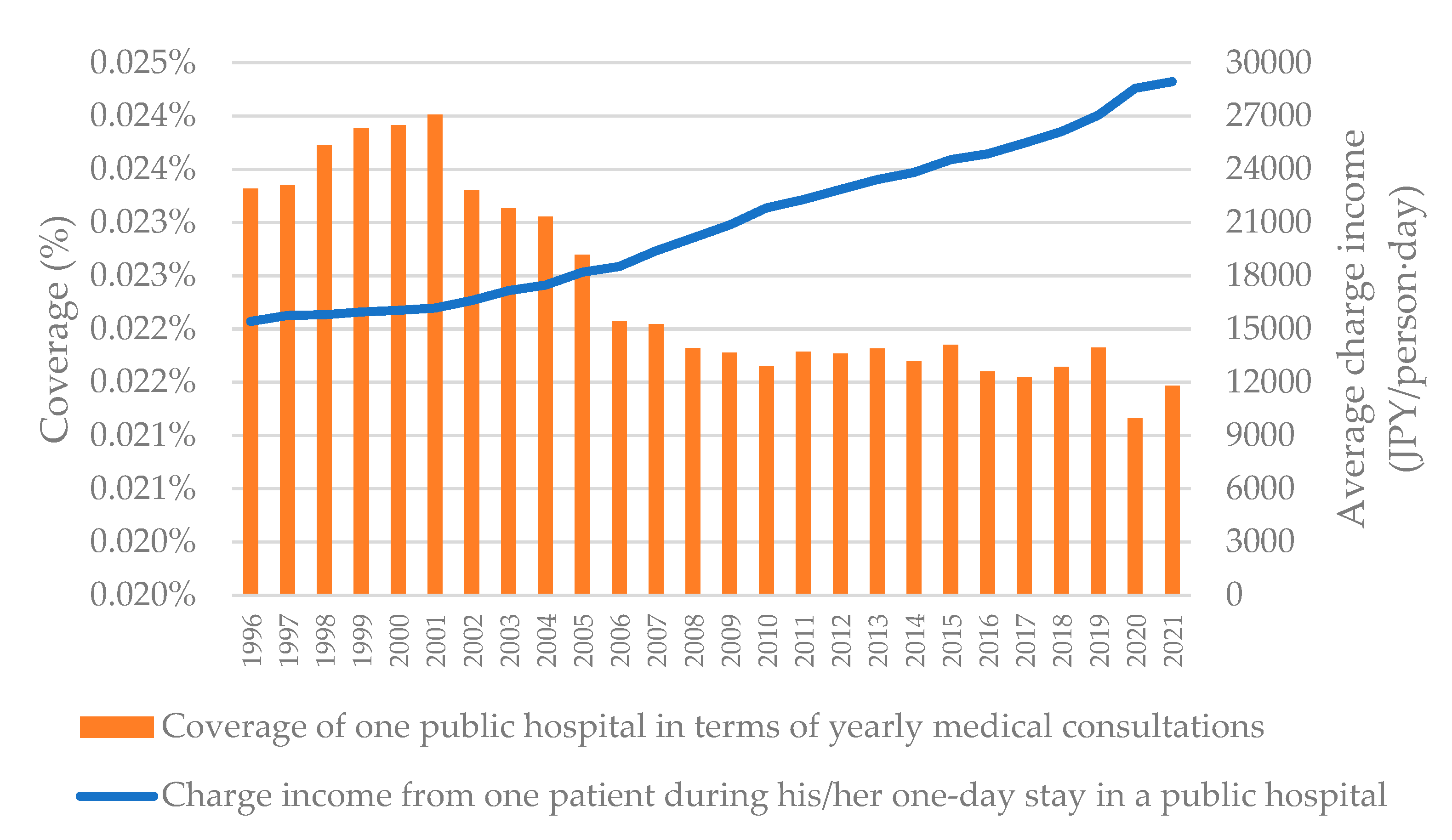

| Coverage of one public hospital in terms of total annual medical consultations in year t (%) | |

| Visit duration for a single consultation to a public hospital including inpatients and outpatients in year t (days/time), here a single consultation of an outpatient is counted as a one-day stay in a public hospital | |

| Type i operating cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital in year t (JPY/day) |

| Statistics | Mark | Influencing factors | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | ① | Population | ① |

| Number of public hospitals | ② | Annual income per capita | |

| Annual income | ③ | Consultation rate by annual income | |

| Number of outpatients per day in public hospitals | ④ | Coverage of one public hospital in terms of yearly medical consultations | |

| Number of inpatients per day in public hospitals | ⑤ | Visit duration for a single consultation at a public hospital including inpatients and outpatients | |

| Number of outpatients per day in all hospitals | ⑥ | Material cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | ⑪/() |

| Number of inpatients per day in all hospitals | ⑦ | Medicine cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | ⑫/() |

| Annual gross number of outpatients in public hospitals | ⑧ | Salary cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | ⑬/() |

| Annual gross number of inpatients in public hospitals | ⑨ | Depreciation cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | ⑭/() |

| Average visit duration of inpatients in all hospitals | ⑩ | Other costs for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | ⑮/() |

| Material costs Medicine costs Salary costs Depreciation costs Other costs |

⑪ ⑫ ⑬ ⑭ ⑮ |

||

| Based on one public hospital | Year | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | million | 125.9 | 126.2 | 126.5 | 126.7 | 126.9 | 127.3 | 127.5 | 127.7 | 127.8 | 127.8 | 127.9 | 128.0 | 128.1 | 128.0 | 128.1 | 127.8 | 127.6 | 127.4 | 127.2 | 127.1 | 127.0 | 126.9 | 126.7 | 126.6 | 126.1 | 125.5 |

| Annual income per capita | million JPY/capita | 3.37 | 3.35 | 3.27 | 3.25 | 3.34 | 3.22 | 3.19 | 3.24 | 3.30 | 3.31 | 3.35 | 3.35 | 3.10 | 3.00 | 3.09 | 3.05 | 3.06 | 3.18 | 3.25 | 3.41 | 3.40 | 3.48 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.32 | 3.51 |

| Consultation rate by annual income | patient-times/million JPY | 1.43 | 1.42 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.42 | 1.47 | 1.43 | 1.37 | 1.31 | 1.29 | 1.24 | 1.20 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| Coverage of one public hospital in terms of yearly medical consultations | % | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.021 |

| Visit duration for a single consultation at a public hospital including inpatients and outpatients | days/time | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 1.51 | 1.53 | 1.54 | 1.55 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.55 |

| Material cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | JPY/patient-day | 1759 | 1808 | 1870 | 1926 | 1940 | 1981 | 2132 | 2247 | 2293 | 2426 | 2449 | 2420 | 2527 | 2603 | 2529 | 2583 | 2617 | 2756 | 2785 | 2874 | 2907 | 3040 | 3096 | 3190 | 3476 | 3712 |

| Medicine cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | JPY/patient-day | 3642 | 3528 | 3388 | 3250 | 3047 | 2889 | 2882 | 2751 | 2688 | 2744 | 2746 | 2827 | 2806 | 2831 | 2845 | 2919 | 2939 | 3024 | 3030 | 3315 | 3318 | 3381 | 3522 | 3829 | 4122 | 4139 |

| Salary cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | JPY/patient-day | 8912 | 9254 | 9409 | 9436 | 9416 | 9479 | 9844 | 10021 | 10253 | 10559 | 10956 | 11451 | 11992 | 12326 | 12432 | 12769 | 13081 | 13335 | 13859 | 14304 | 14941 | 15250 | 15637 | 16096 | 18981 | 18693 |

| Depreciation cost for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | JPY/patient-day | 955 | 1007 | 1078 | 1168 | 1180 | 1195 | 1272 | 1363 | 1401 | 1473 | 1560 | 1648 | 1734 | 1739 | 1735 | 1751 | 1785 | 1869 | 2284 | 2368 | 2468 | 2517 | 2571 | 2603 | 2894 | 2790 |

| Other costs for one patient during his/her one-day stay in a public hospital | JPY/patient-day | 2642 | 2757 | 2838 | 2928 | 3053 | 3175 | 3409 | 3646 | 3906 | 4190 | 4522 | 5027 | 5397 | 5529 | 5729 | 5809 | 5964 | 6275 | 6367 | 6434 | 6484 | 6658 | 6815 | 7057 | 7262 | 7173 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).