Introduction

The head and neck region, though accounting for approximately 9.0% of the body's surface area, is disproportionately susceptible to malignant melanomas, representing nearly 20% of all cases. This increased prevalence in older individuals can be attributed to the growing life expectancy in recent years. Notably, scalp melanoma, constituting 35% of all head and neck melanomas, carries the highest mortality rate, with a 10-year survival rate of only 60%.[1, 2] NCCN guidelines recommend excising melanomas with a safety margin of 5 mm to 20 mm, and deeper excisions are necessary to reduce local recurrence, especially for lesions greater than 2 mm in depth. [

3]

Scalp defects have limited reconstructive options due to lack of surrounding tissue and tension. Scalp reconstruction, in particular, is hindered by the need to preserve hair follicles and maintain natural skin contours. [

4]

Therefore, the use of a local flap has the advantage of preserving hair follicles and skin contour. However, unlike other parts of the body, there is tension and skin laxity that limits tissue advancement. Here we would like to present the method of local flap for scalp melanoma with surgical technique to show the limitations of free flap or better aesthetic result.

Case report

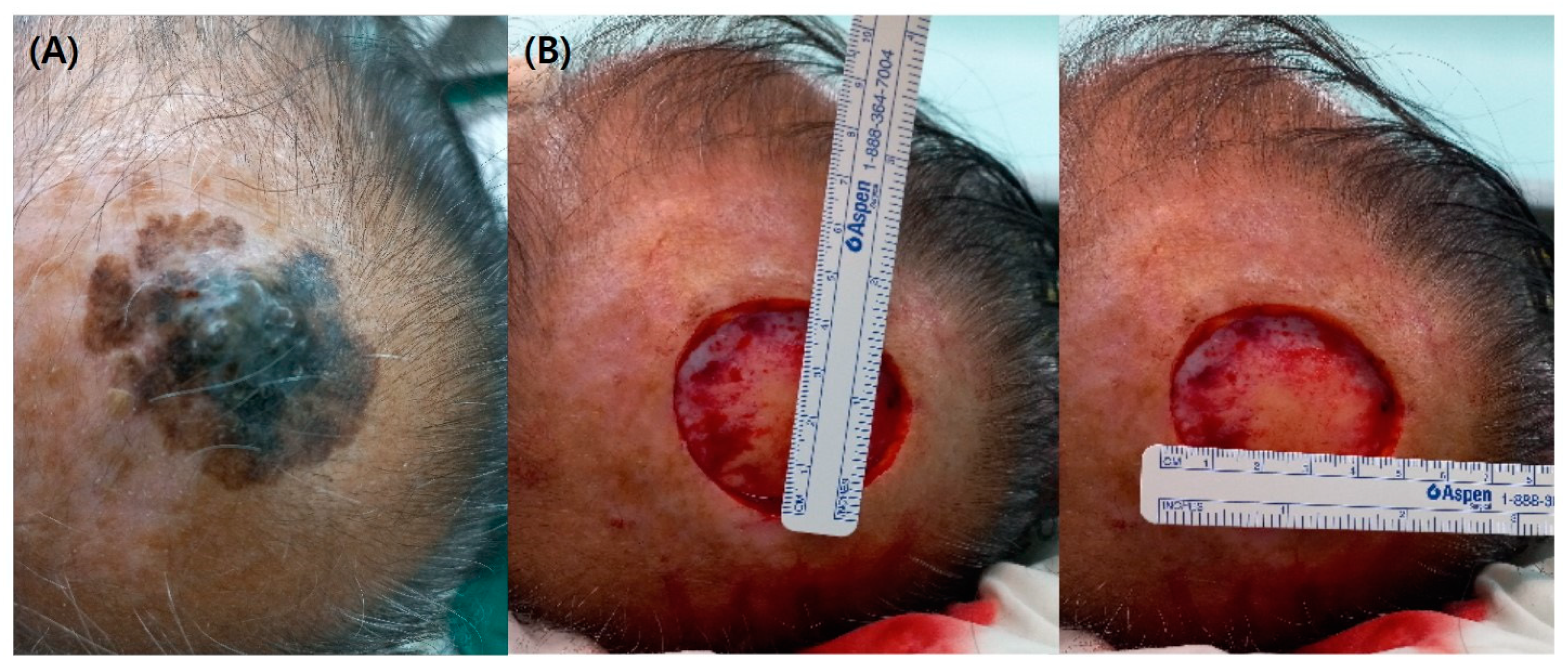

A 77-year-old man with a long history of moles on his scalp, which had increased in size over the past two years. He underwent a biopsy at a local hospital and was diagnosed with a spread of atypical spindle-shaped ovarian cells in the dermis, most likely malignant melanoma. At the time of presentation, the size of the mole was approximately 50 x 45 mm, and a scalp defect of at least 90 x 85 mm was expected if a wide excision was performed. Therefore, a free flap reconstruction was considered to be stable.

However, the patient had a history of angina and was unwilling to undergo a long operation due to his advanced age. In fact, he had reached the stage of refusing surgery and testing, so he needed excision and reconstruction without burdening the patient. According to the NCCN guidelines for malignant melanoma, the surgical margin was 2.0 cm, and the bone needed to be removed with some burr.[

3]

To minimize defects, the actual size of the melanoma was required. So, a staged excision was planned. The first excision was performed along the border of the visually distinguishable mole, and after the biopsy, the resection margin was measured again to plan the post-excision reconstruction. The actual depth was 8 mm, requiring burr holes, so skin graft reconstruction was ruled out. [

5]

The O-Z flap is a local flap often used for scalp defects and the O-Z flap is a modified rotational flap in which the defect is shaped like an 'O' and the incision line is shaped like a 'Z', hence the name O-Z flap. [6, 7] This flap had the advantage of covering a large defect.

The procedure is as follows.

First excision: The excision line was drawn along the margin of the visually distinguishable mass and resected. At that point, the depth including the periosteum was removed. Depending on the results of the biopsy, a second operation would have been performed after the boundaries and margins of the actual mass had been confirmed. (

Figure 1)

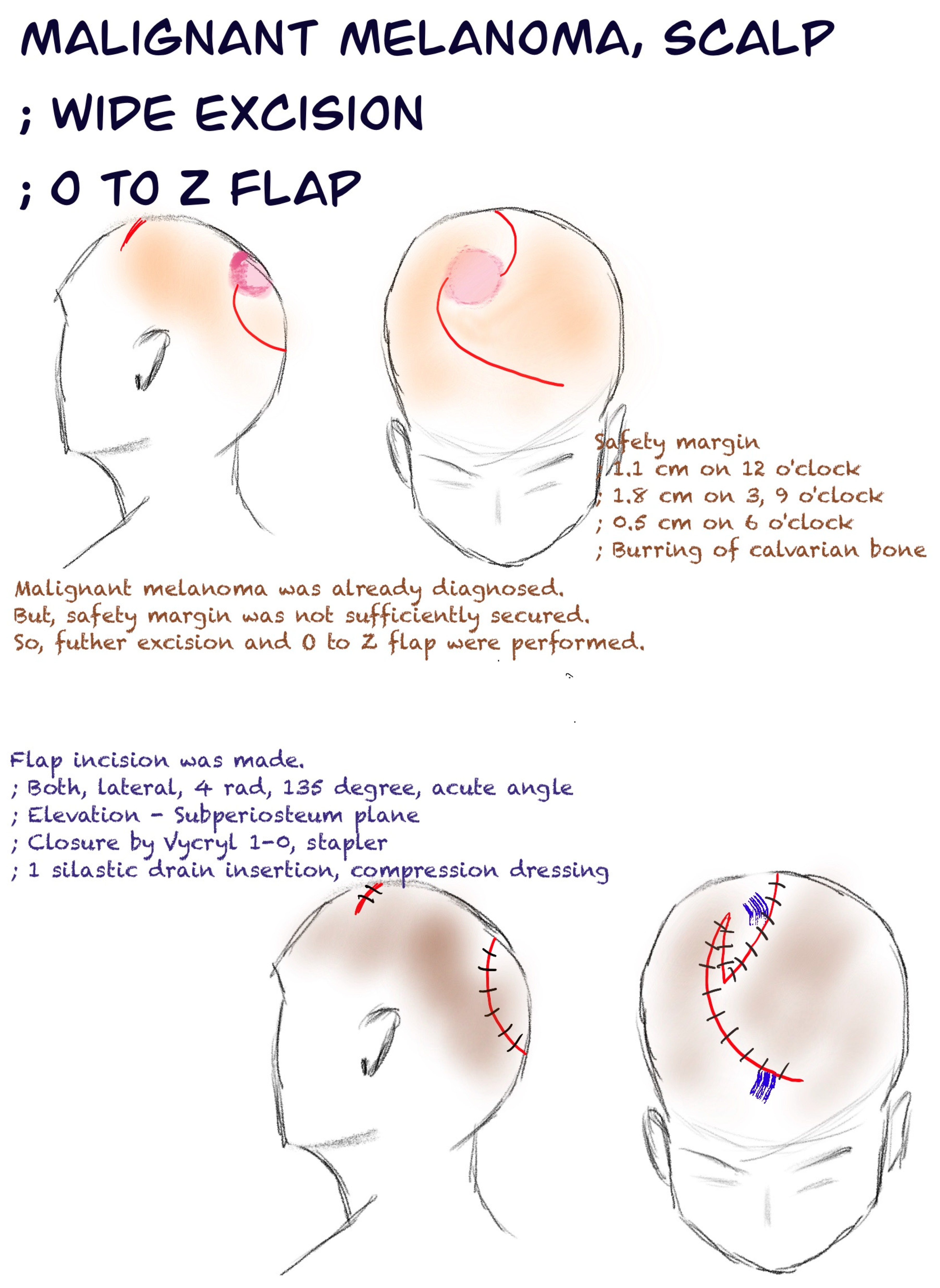

Second excision and flap design: After the biopsy results from the first surgery, the second surgery was started (about 5 days later). At the start of surgery, the first step was to accurately delineate the excision boundaries to ensure an adequate margin of safety. The first postoperative histopathological examination of this patient had shown a safety margin of 0.9 cm at 12 o'clock, 0.2 cm at 3 o'clock and 9 o'clock, and 1.5 cm at 6 o'clock.

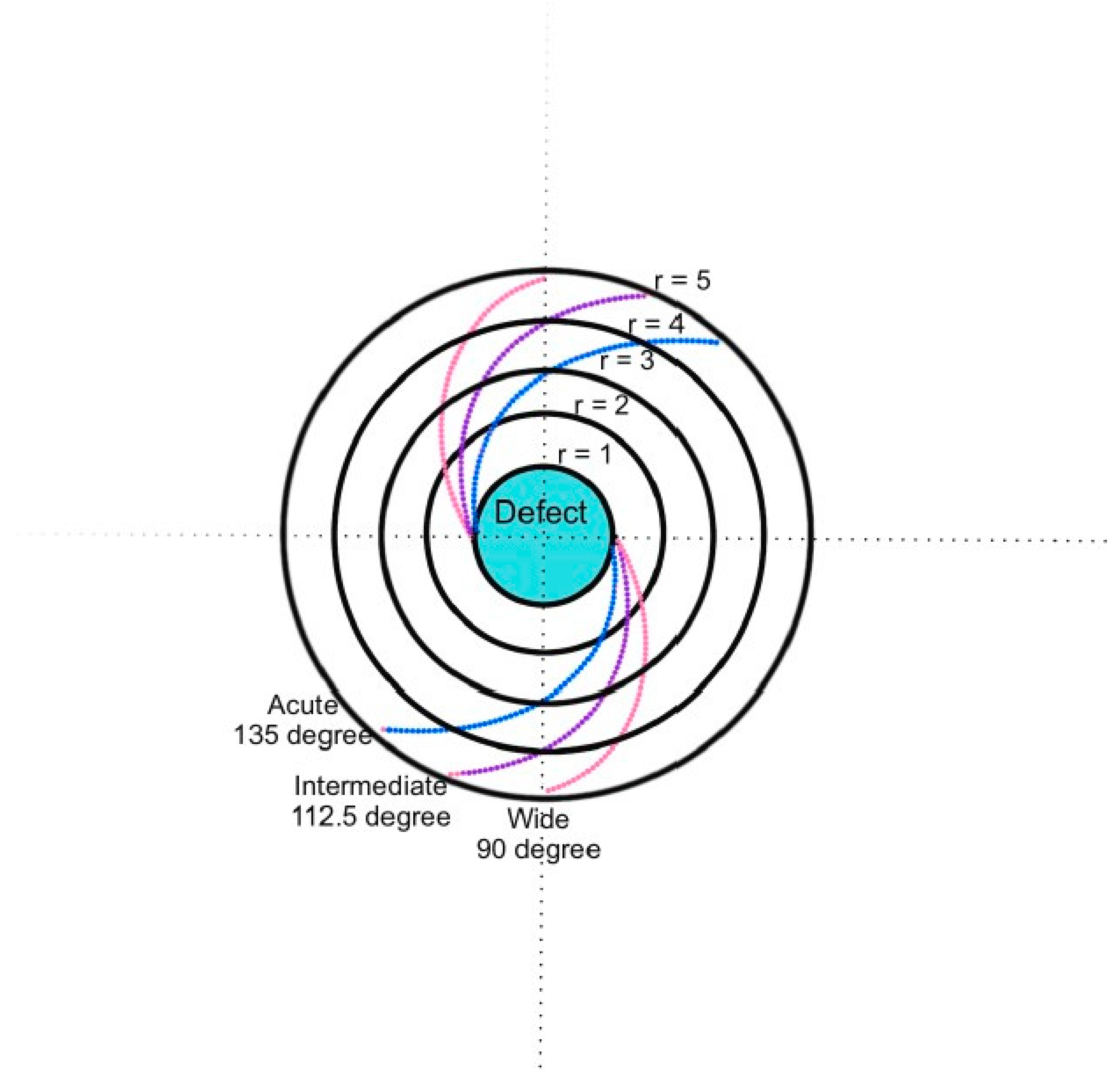

Flap configuration: The flap was then carefully designed, taking into account the expected size of the defect. Careful attention was paid to the angle of flexion and the length of the incision line. (

Figure 2)[

8]

Wide excision: Once the surgical plan had been established, a wide excision of the targeted mass was performed. This included the removal of the superficial portion of the calvarial bone, including the periosteum, facilitated by the use of a burr.

Flap elevation: The flap was then carefully elevated, adhering to the predetermined flap design and encompassing the galea layer.

Flap approximation: Precise approximation of the two ends of the flap followed, culminating in its secure placement to adequately cover the surgical defect.

Suture and fixation: Notably in this particular case, both flaps were created with a 4 Rad, 135-degree acute angle and then anchored in place using Vicryl 1-0 sutures and secure stapler sutures after the insertion of a penrose drain. (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4)

After surgery, the patient's defect was completely covered without flap margin necrosis. (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6)

Discussion

The resection margin guidelines for melanoma provided by NCCN are determined based on tumor thickness. For in-situ melanoma, it is set at 0.5-1.0 cm, for melanoma with a thickness of 1.0 mm or less, it's 1.0 cm, for melanoma with a thickness of 1.0-2.0 mm, it's 1-2 cm, and for melanoma with a thickness of 2.0 mm or more, it's 2.0 cm. Additionally, for melanoma with a thickness of 0.8 mm or greater, sentinel lymph node biopsy is also necessary.[

3]

The O-to-Z flap is a bilobed advancement flap used to close skin defects on the opposite side of the defect. [

6] It is created by making two curved incisions on opposite sides of the roughly circular defect. Each flap is advanced, rotated and secured at a 90° angle from the incision point. The two flaps may be the same length or different lengths, depending on the available surrounding tissue. The final closure results in a scar that resembles a zigzag pattern, similar to the letter "Z". [6-8]

Reconstruction options for scalp defects include primary closure, skin graft (full-thickness or split-thickness), local flap and free flap. In this particular case, skin grafting was not considered due to the lack of periosteum, leaving a choice between local flap and free flap reconstruction.

Opting for free flap reconstruction has the advantage of ensuring a sufficiently large flap size to effectively cover extensive defects. However, it is important to consider the potential differences in skin contour, texture, and hair distribution that may be seen postoperatively. There is also a risk of partial or total flap necrosis in certain cases. And this option requires skilled microsurgical techniques and prolonged operation times. [4, 9, 10]

The scalp is a tissue area characterized by a limited donor site selection, in particular including hair follicles. When reconstructing, it is imperative to ensure that the skin contour remains congruent with the adjacent tissue and that the integrity of the hair follicles is meticulously preserved. It is characterized by high tensile strength, which presents a challenge in achieving effective approximation during reconstructive surgery. However, the scalp has a rich blood supply, is less likely to have marginal necrosis, and has significant advantages in skin texture and contour and hair distribution using local flap. It can also be seen that wrinkle deformity is sufficiently improved by scalp remodeling.[11-13]

Limitations

Due to the long length of the scar, some patients complain of cosmetic discomfort. However, compared to a skin graft or free flap, the hair follicles are preserved and the skin contour is not different, so it can be seen that it is a much better cosmetic improvement than other reconstruction methods. In addition, due to the tension of the scalp flap, patients complained of headaches during the recovery period, but this issue tends to improve in the later stages of recovery and can be effectively addressed by proactive pain management strategies implemented during the period of discomfort.

Conclusion

Through the method of scalp reconstruction using the O-Z flap, it is a flap that can be considered for patients who cannot afford a free flap due to age, general condition. In addition, it can be used for scalp skin cancer, including melanoma, by providing a safety margin and a surgical plan through staged excision for cancer.

References

- de Giorgi, V.; Rossari, S.; Gori, A.; Grazzini, M.; Savarese, I.; Crocetti, E.; et al. The prognostic impact of the anatomical sites in the 'head and neck melanoma': scalp versus face and neck. Melanoma Res 2012, 22, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.S.; Read, T.; Lonne, M.; Barbour, A.P.; Wagels, M.; Bayley, G.J.; et al. Primary cutaneous melanoma of the scalp: Patterns of recurrence. J Surg Oncol 2017, 115, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetter, S.M.; Thompson, J.A.; Albertini, M.R.; Barker, C.A.; Baumgartner, J.; Boland, G.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Melanoma: Cutaneous, Version 2. 2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021, 19, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seline, P.C.; Siegle, R.J. Scalp reconstruction. Dermatol Clin 2005, 23, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.I.; Balch, C.M. Excision Margins of Melanoma Make a Difference: New Data Support an Old Paradigm. Ann Surg Oncol 2016, 23, 1053–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wei, P.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, K.; Lin, B.; et al. Use of the O-Z Flap to Repair Scalp Defects After Cancer Tumor Resection. J Craniofac Surg 2022, 33, 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regula, C.G.; Liu, A.; Lawrence, N. Versatility of the O-Z Flap in the Reconstruction of Facial Defects. Dermatol Surg 2016, 42, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, E.D.; Quinn, F.B.; Calhoun, K.H. Optimal design of O-to-Z flaps for closure of facial skin defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003, 5, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.K.; Bader, R.D.; Ewald, C.; Kalff, R.; Schultze-Mosgau, S. Scalp defect repair: a comparative analysis of different surgical techniques. Ann Plast Surg 2012, 68, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Wan, H.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. Pre-Expanded Latissimus Dorsi Myocutaneous Flap for Total Scalp Defect Reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg 2020, 31, e151–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachiewicz, A.M.; Berwick, M.; Wiggins, C.L.; Thomas, N.E. Survival differences between patients with scalp or neck melanoma and those with melanoma of other sites in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Arch Dermatol 2008, 144, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladden, M.J.; Nieweg, O.E.; Howle, J.; Coventry, B.J.; Thompson, J.F. Updated evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma: definitive excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma. Med J Aust 2018, 208, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, D.; Hubertus, A.; Arkudas, A.; Taeger, C.D.; Ludolph, I.; Boos, A.M.; et al. Scalp reconstruction: A 10-year retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017, 45, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).