1. Introduction

The examination of the outcomes obtained from the three courses, both in the pretest and post-test stages, involved rigorous analysis. By reversing the scoring of negative statements and performing meticulous calculations, we sought to unveil the substantial changes that unfolded in the realms of skills, sub-skills, and dispositions. Predominantly, the most remarkable enhancements transpired within the domain of skills, with comparatively limited advancements observed within dispositions. This distinction underscores our partial affirmative response to the primary research question (Q1: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships for all students from all three classes considered together?).

The detailed examination of the results, as depicted in the presented table, elucidates the most prominent shifts within the skills sphere. Both the overarching categories of interpretation and explanation, and their corresponding subcategories—such as clarifying meaning, assessing claims, stating results, justifying procedures, and presenting arguments—revealed significant changes. This robust progression was notably attributed to the comprehensive exposure that students encountered during the courses. They engaged not only with theoretical content but also grappled with diverse real-life cases, amplified by the inclusion of perspectives from labor market representatives. Consequently, their proficiency in interpreting data and information, assessing claims, and presenting coherent arguments demonstrated substantial growth.

The intricate nature of critical thinking, a psychological phenomenon, renders its enhancement challenging to attribute solely to specific methods or pedagogical approaches. The courses embraced an inquiry-based, constructivist approach, enriched with a diverse array of teaching methods and case studies—attributes intrinsic to labor market-oriented pedagogy. This comprehensive strategy aimed at fostering both skills and dispositions, yielding discernible improvements in selected facets.

However, it is noteworthy that despite these targeted endeavors, not all dispositions exhibited significant progress. This could be attributed to the intricate nature of these traits, resembling personality facets that necessitate sustained cultivation over an extended duration. The essence of Aristotle’s critical spirit, encompassed within these dispositions, requires substantial and prolonged efforts for full development.

Deeper scrutiny of the three pilot courses unraveled distinct disparities in initial scores among students. Notably, disparities were observed in the “Interpretation” skill and “Perseverance” disposition. Post hoc testing using the Bonferroni method confirmed these differences between the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course and the Virtual Learning Environments in Economics course. Remarkably, participants in the Virtual Learning course consistently exhibited higher average scores in both “Interpretation” and “Perseverance” when compared to their counterparts in the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course. The progression analysis for the three pilot courses—Business Communication (n=31), Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting (n=32), and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics (n=18)—employed the GLM-Univariate ANCOVA test. However, it’s crucial to exercise caution while interpreting these findings, as the assumption of prior equality among groups in the covariate was not consistently met for “Interpretation” and “Perseverance”. In essence, while no substantial divergences in critical thinking skills emerged across the three pilot courses, notable variations surfaced within the integrated scores of CT dispositions. This variation was particularly apparent in the Business Communication and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics courses, indicating higher dispositions scores. This discrepancy was further reflected in specific dispositions like “Attentiveness,” “Open-Mindedness,” and “Intrinsic Goal Motivation,” delineating unique trajectories in different courses. In sum, the application of the GLM-Univariate ANCOVA test shed light on the cohesive gains in critical thinking skills across the pilot courses. However, noteworthy differences emerged in the composite dispositions scores, showcasing higher scores in Business Communication and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics courses. This distinction was further highlighted in specific dispositions, emphasizing the diversity of outcomes across the courses.

These findings pave the way for a deeper exploration of research questions 2, 3, and 4. As we delve into an individual course analysis, thorough examination of the data and its interpretation reveals substantial advancements in both skills and dispositions (

Table 2. Collectively, our responses to the research questions remain partially affirmative, as statistically significant improvements were witnessed in skills but not consistently in dispositions for all three courses—excluding a few significant differences in Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting, notably in “Open-Mindedness” and the total dispositions score.

This transformative outcome can be attributed to the immersive nature of labor market-oriented interventions. These interventions capitalized on an array of interactive teaching methods, harnessed the potential of diverse learning resources, and actively engaged students in discovery-based processes. A striking exemplification of this approach can be observed in the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course. Here, students were immersed in multifaceted practical situations, including role transitions from participants to trainers. The integration of interactive tools like Google Drive facilitated metacognition, interpretation, and explanation. The instructor’s guidance in discerning pedagogical actions bolstered awareness and open-mindedness, ultimately culminating in enriched interpretation and explanation skills.

The critical thinking journey across these experimental courses mirrored a gradual yet impactful transformation. As the integration of labor market perspectives, interactive techniques, and engaging learning platforms converged, students’ interpretive prowess and explanatory skills flourished. This journey illuminated the potential of innovative pedagogical paradigms in fostering critical thinking competencies, underscoring the symbiotic relationship between education and real-world application.

3. Critical thinking in Business of Economics. Teaching together with labour market organizations

In the context of a constantly changing labour market, a new attitude is emerging that the success of an organisation is ensured by its human resources, so the voice of employers calling for the importance of CT skills among employers is being increasingly heard [

12]. According to Elicor [

13], CT can be an essential tool for the management of organizations, contributing in a fundamental way to the identification of the best practical solutions, given the conditions of the business environment that require a high and constant level of effectiveness and competitiveness. Today’s employees need to be able to generate new ideas and ways of working, while also embracing old techniques and systems of working to ensure competitive advantage [12, 14].

The ability to think critically enables employees to think creatively, independently, adopt decisions and take the necessary measures to counteract the negative effects of dysfunctions that occur [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 12] as well as to analyse the most complex problems in order to achieve the desired results [

20]. In fact, in 2006 a consortium of American universities surveyed ranked CT higher than “innovation” and “application of information technology” as skills [

21]. Thus, although it is well known that critical thinking should occupy an important place in education systems [22, 23], since the earliest times, from the time of John Dewey, when reflective thinking was promoted [

24], today more and more labour market organisations are highlighting this. These new educational approaches are designed to facilitate interdisciplinary thinking and lead to the cultivation of the capacity to act, self-determination and the ability to reflect.

Indrasiene and colleagues [

12] consider that in the context of the labour market, the ability to think critically helps employees to understand new concepts, to adopt decisions in critical situations, to engage positively and productively in activities, making the connection between theoretical topics and practical situations.

In this process, teachers have a very important role to assume, as it has been demonstrated that the development of students’ ability to think critically is not a direct result of higher education [25, 26, 27], they need explicit and specialised instruction to improve their critical thinking skills [28, 29, 27]. Regarding the academic level it is already known that the development of critical thinking skills should be integrated as part of formal education. At the educational level the ability to think critically is not only considered from a competitive point of view [

30], but also because it ensures the mature development of a person’s, of the way of thinking so that he or she becomes independent, proactive, creative and capable of adapting to a wide range of social, economic, political and social circumstances [31, 32, 33, 12]. Consequently, critical thinking skills are an outcome of the knowledge accumulated in higher education, reflected in the missions and government policies of universities, textbooks, assessment forms and grading criteria [

34].

Often teachers’ lack of knowledge as well as lack of experience in CT is one of the main reasons why the concept of critical thinking is often not included in different parts of teaching [35, 36]. In the area of education, there is still much debate about whether the concept should be included in other courses that are designed to develop certain professional skills among students or whether a course should be made exclusively dedicated to developing critical thinking skills among students [

37]. Regardless of how the concept of critical thinking is approached, it is a skill that should be mastered by every student, so every teacher should be encouraged to see CT as part of the learning outcomes of every subject, the use of this skill representing a ‘thinking tool’ for students, respectively for the future period when they will face different business problems [

21]. In teaching disciplines from the economics field as well as other fields, however, it is difficult to develop guidelines on how critical thinking should be stimulated throughout the curriculum based on current research findings [38, 28]. Anyway, most economists consider critical thinking skills to be an objective that should be pursued in economics courses [

28], in response to employers’ demands that universities and colleges train graduates who are able to make connections in order to solve complex problems [

39]. Also, The OECD also considers CT to be an economic, political and psychological issue, being a higher-order skill whose main purpose is to evaluate a theory, statement or idea through a whole process of questioning and analysis [

40].

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Variables

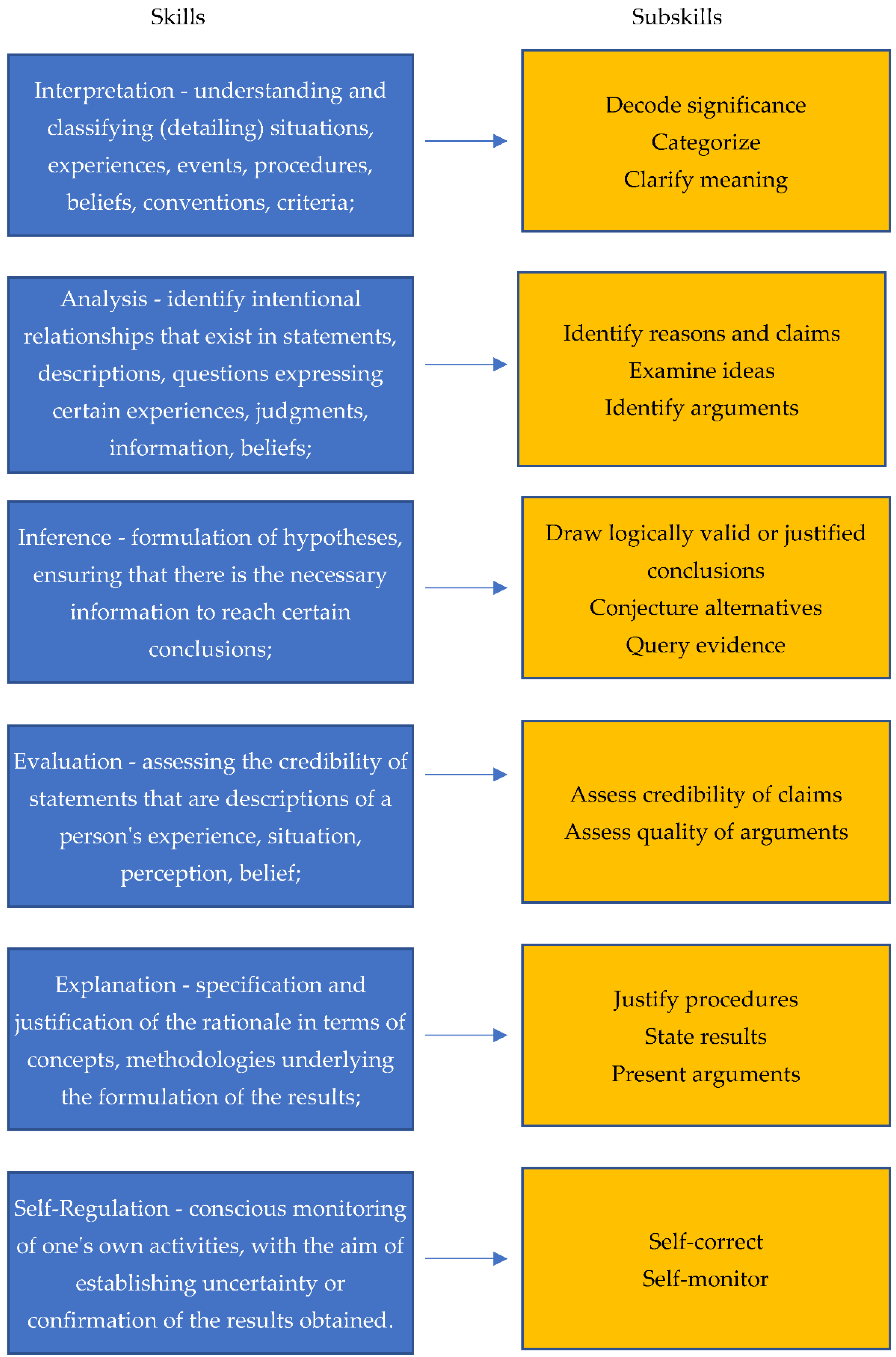

The dependent variable is critical thinking (CT). The definition used for the following research is in line with Peter Facione [

4]. In order to operationalize the CT skills and dispositions we used two tests: a dispositions questionnaire „SENCTDS - The Student-Educator Negotiated Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale”, developed by Quinn and colleagues [

41] and another skills questionnaire designed by Nair [

42] “Critical Thinking Self-Assessment Scale – CTSAS”. Both tests were joined into one single test thus, the final questionnaire consisted of 81 items (21 SENCTDS questions and 60 CTSAS questions). This form of the two combined tests was validated by Payan-Carreira and colleagues [

43]. The two tests are based on Facione’s classification for measuring critical thinking skills (

Figure 1).

Certain elements combine the specific classical dispositions of the Facione CT (inquisitiveness, systematicity, analyticity, truth-seeking, open-mindedness, self-confidence, maturity) [

44] forming new dimensions that are anticipated to play a significant role in achieving success in academia and the labour market [

45]. Thus, the resulting components encompass the six distinct dimensions of these: Reflection, Open-mindedness, Attentiveness, Organisation, Intrinsic Goal Motivation and Perseverance.

The independent variable is represented by three curricula resulted from business-university collaboration. University teachers (one lecturer and two professors) designed three courses in collaboration with two trainers specialized in banking and financial consultations.

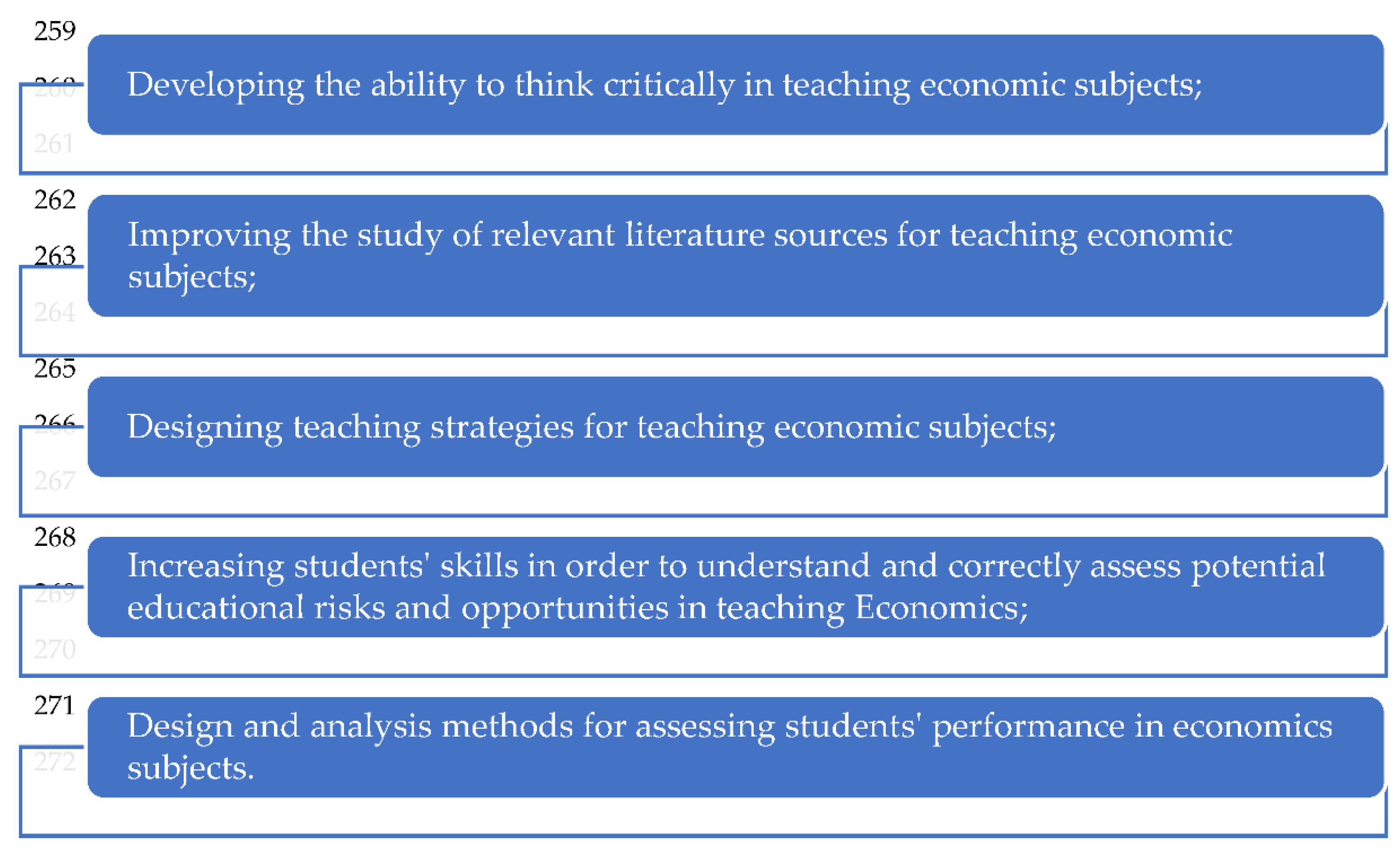

Throughout the first course, Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting students will gain a better understanding of concepts related to Economics and Accounting, as well as information, regarding the educational system and school curriculum [

46]. The main competences that students have developed throughout the course are represented in the figure below [

46].

Figure 2.

Skills developed by students from the Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting course.

Figure 2.

Skills developed by students from the Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting course.

Within this course, instructors devised diverse practical scenarios to engage students. One notable learning scenario entailed students participating in a training session where they were learners, followed by a subsequent meeting in which they assumed the role of the instructor. To support this process, students utilized an interactive tool on Google Drive that facilitated metacognition, interpretation, and explanation. The approach initiated with students delving into their recollection of content, subsequently reconstructing how the instructor conducted the session. This reflective phase aimed to transform the experience into a valuable educational encounter. Once this metacognitive stage concluded, the higher education (HE) teacher introduced various teaching methods and strategies. This step aimed to elucidate the underlying pedagogical intentions of the instructor’s actions, fostering awareness and cultivating open-mindedness. To further develop open-mindedness, dedicated classes conducted by the HE teacher were instrumental. During these sessions, students were tasked with devising multiple didactic scenarios targeting the same operational objectives. These scenarios encompassed varied methods, strategies, learning environments, and instructional materials. The HE teacher employed systematic observation ranking sheets to gauge the progression of open-mindedness [

48].

Throughout this process, both the HE teacher and the trainer specializing in learning management systems (LMO) offered consistent and valuable guidance to students. This collaborative input enabled students to master the art of discerning pertinent information for crafting lesson plans specifically tailored to economics subjects. These lesson plans effectively aligned with the school curriculum, leading to substantial improvements in interpretation and explanation skills.

The second course, Virtual Learning Environments in Economics was aimed at future Economics teachers and focuses on the following areas: writing scientific materials, selecting the most effective teaching strategies through data processing, creating interactive platforms in the virtual environment according to the students’ needs [

46]. At the end of this course, students - future Economics teachers were able to use effectively digital content and communication channels characteristic of the virtual environment such as Canva, Google sites, Microsoft package. Students’ assignment encompassed the creation of virtual learning environments, a process that demanded careful consideration of subject matter and theoretical underpinnings. Drawing from best practice examples and insightful case studies, students embarked on the journey of crafting interactive platforms tailored to optimize educational activities within a virtual setting [

46]. This immersive experience unfolded through a meticulous sequence. Beginning with a meticulous design phase for the chosen IT solution, students meticulously defined objectives and methods for content transmission. They proceeded to formulate and articulate the content, with each step scrutinized and guided by their instructor. From the initial stages to the final implementation of interactive solutions, the teacher remained a constant presence, offering guidance, evaluation, and refining techniques. Simultaneously, students engaged in a parallel endeavour—crafting diverse interactive presentations on various Economics topics. Using the Canva platform, they synthesized the information imparted by their instructors. This approach aimed to bolster their analytical and research skills as they delved into the material, extracting essential data to address the assigned topics.

In a distinct learning avenue, the “Business Communication” course aimed to equip students with comprehensive knowledge about various communication types—verbal, nonverbal, and paraverbal [

49]. Having received the theoretical foundation, students transitioned into the realm of practical application, where they dissected the advantages, drawbacks, and nuances of these communication modes. This process encouraged critical thinking and the synthesis of theoretical insights with real-world scenarios. A significant portion of the course was devoted to exploring cross-cultural communication dynamics. Students embarked on research endeavours, discerning the significance of colour symbolism across different countries and cultures. Their findings culminated in enlightening presentations, highlighting how colours can unwittingly serve as barriers or bridges in diverse global business contexts. Furthermore, students undertook the intricate task of analysing authentic business situations, collaborating with labour market representatives. This involved immersing themselves in multifaceted project scenarios and assuming various roles, including project team members and managers. Through a comprehensive analysis of each stakeholder’s perspective, students discerned problems, identified root causes, and proposed strategic improvements. The curriculum also embraced the critical notion of body language, office layout, and workspace design in shaping collaborative interactions within the business realm. Students received valuable insights from their instructors, enabling them to decipher the nuances of nonverbal cues, office dynamics, and spatial arrangements within an international context. Through thought-provoking exercises, they deepened their comprehension of how these elements influence effective communication and cooperation.

In essence, these courses provided a multi-dimensional learning experience, where theoretical foundations were translated into practical skill sets. Students navigated the complex landscape of virtual learning design, communication dynamics, and real-world problem-solving, emerging with enriched competencies poised for application in their academic and professional journeys.

All three courses had the goal of enhancing critical thinking (CT) skills and attitudes using an inquiry-based, constructivist teaching method. Each module included distinct learning assignments and evaluation tasks.

Based on the needs analysis [

47], it was discovered that students preferred a bottom-up teaching approach, commencing with their own experiences and progressively linking concepts before delving into the theoretical aspects of the lesson. The LM (Lifelong Learning Model) instructor was inclined toward this strategy, with half of the lessons conducted solely by the LM instructor or in collaboration with the HE (Higher Education) teacher. These sessions employed techniques like discovery-based learning, problem-solving, project-based learning, case studies, and role-playing to foster skill development, along with metacognitive strategies to cultivate awareness, open-mindedness, and intellectual humility.

Collaborating with the LM partners, the curriculum employed case studies, trigger scenarios (such as sets of images), and other learning scenarios. These compelled students to analyse specific situations, following the framework commonly used by the LM partners. Each student group received a case study or problem to scrutinize, generate questions, define concepts, make judgments, and engage in discussions regarding their thoughts and decisions. After contemplating and debating the presented topic, students were expected to propose a decision or solution, considering new contextual elements, motivations, and actual client needs. The LM partner occasionally participated by presenting a training section, akin to what they provide in-service training, with students assuming trainee roles. This served to introduce various approaches for activity design or addressing communication challenges.

The university-business collaboration was comprehensive, and all classes were collaboratively designed to ensure a unified perspective on CT development. The total curriculum time was divided between the LM and the university teacher. While the trainer held the primary teaching role, the university teacher was consistently present in the classroom. Due to time constraints, LM trainers were absent from the university teacher’s sessions. The classes were interconnected, with LM trainers and university teachers conducting activities aligned with the scheduled theme. LM teaching primarily employed practical techniques, drawing from real-life examples in banking or training settings. Students were assigned specific tasks and encouraged to think as if they were employees, necessitating the application of various CT skills outlined in earlier sections. University teachers utilized top-down methods in their educational activities, employing concept-driven and concept-building tasks to bridge the experiential knowledge acquired from the LM trainer with current theoretical frameworks.

Considering the scope of the courses and the fact that the research aims to assess dispositions and skills specific to critical thinking, in order to analyse the degree of improvement in CT ability, students were tested before and after the finalisation of the courses.

4.2. Method

The method chosen to check the degree of improvement in students’ ability to think critically was quasi-experiment. We have chosen this method because it is impossible to control the action of all factors which may or might have in the past influenced critical skills and dispositions. Since there might be others sources that influence CT, but also our intervention, we assume that testing students before and after the proposed classes developed together with our labour market partners, there are strong chances the observed difference to be accounted by our intervention. Hence, best solution is to get our research through a quasi-experimental design to test the following research questions:

Q1: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships for all students from all three classes considered together?

Because we may justly think that the three groups are starting from different levels of critical thinking, we propose the following research questions, searching for each group achievement.

We shall check the pretest data to confirm the difference between groups.

Q2: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships in Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting class?

Q3: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships in Virtual Learning Environments for Economics class?

Q4: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships in Business Communication class?

To interpret the data obtained before and after the three courses, Paired Sample T-Test was applied, using Jamovi software. The results obtained in the pre-test stage were noted with T1, while those derived from the final test were marked with T2. The six main categories of skills studied were: analysis, interpretation, explanation, evaluation, inference, self-regulation. The dispositions categories included: intrinsic goal motivation, attentiveness, open mindedness, organization, reflection, perseverance. For skills, the subcategories resulting from the applied questionnaire were also studied: analysis (examining ideas, detecting arguments, analysing arguments), interpretation (categorization, decoding significance, clarifying meaning), explanation (stating results, justifying procedures, presenting arguments), evaluation (assessing claim, assessing arguments), inference (querying evidence, conjecturing alternatives, drawing conclusions), self-regulation (self-examining, self-correction).

4.3. Participants

The final sample consists of 81 students (68 female and 13 male) who participated in the study: 32 students of Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting class – Bachelor level, second year; 18 students of Virtual Learning Environments class – Master level, second year; 31 students of Business Communication class – Master level, second year. The initial sample consisted of 143 students, but only 81 completed both the pre- and post-tests. We planned three test sessions, pre-test, mid-test, and post-test, but we had to exclude the mid-test because the same students did not complete the pre-test and the post-test. A reward was set for students who participated, 30% of the final grade was considered fully completed if a student attended at least 60% of the classes and took the critical thinking tests. Participants in the three courses ranged in age from 21 to 50.

4.4. Procedure

The first course, Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting, had a duration of 14 weeks (2 hours/week) and was held from October 2021 to January 2022. The number of interventions from representatives of labour market organisations was 8 interventions (16 hours in total).

The second course, Virtual Learning Environments in Economics has been conducted from February to May 2022, with a total duration of 14 weeks (2 hours/week). The number of interventions from labour market trainers was 5 interventions (10 h in total).

The last experimental course, Business Communication, has been implemented in the second semester of the school year 2021-2022 (February - May 2022) for a total duration of 13 weeks (2 hours/week). Labour market representatives had 7 interventions (14 hours total). Critical thinking self-assessment tests were administered in the first, the seventh and the last week of the class, on all three classes.

5. Results and discussions

Strictly analysing the results obtained at the level of the three courses in the pretest and in the post test, after scoring the negative statements/items in reverse and after performing the necessary calculations, we shall present the main changes resulted at the level of skills, sub-skills, dispositions.

Table 1.

Skills/dispositions developed by students during the three experimental courses (T1 - pre-test; T2 - post-test).

Table 1.

Skills/dispositions developed by students during the three experimental courses (T1 - pre-test; T2 - post-test).

| Skills/dispositions |

Paired Differences |

t |

df |

Sig.

(2-tailed) |

| Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

| Lower |

Upper |

| Pair 2 |

Interpretation |

Clarifying meaning_T2 - Clarifying meaning_T1 |

1.827 |

3.768 |

0.419 |

0.994 |

2.660 |

4.365 |

80 |

0.000 |

| Pair 7 |

Evaluation |

Assessing claim_T2 - Assessing claim_T1 |

0.457 |

2.019 |

0.224 |

0.010 |

0.903 |

2.036 |

80 |

0.045 |

| Pair 12 |

Explanation |

Stating results_T2 - Stating results_T1 |

0.802 |

2.182 |

0.242 |

0.320 |

1.285 |

3.310 |

80 |

0.001 |

| Pair 13 |

Explanation |

Justifying procedures_T2 - Justifying procedures_T1 |

0.765 |

2.341 |

0.260 |

0.248 |

1.283 |

2.942 |

80 |

0.004 |

| Pair 14 |

Explanation |

Presenting arguments_T2 - Presenting arguments_T1 |

2.716 |

6.431 |

0.715 |

1.294 |

4.138 |

3.801 |

80 |

0.000 |

| Pair 17 |

Interpretation_T2 - Interpretation_T1 |

2.654 |

6.349 |

0.705 |

1.251 |

4.058 |

3.763 |

80 |

0.000 |

| Pair 21 |

Explanation_T2 - Explanation_T1 |

4.284 |

9.142 |

1.016 |

2.262 |

6.305 |

4.217 |

80 |

0.000 |

| Pair 23 |

CT Skills total score_T2 - CT Skills total score_T1 |

12.519 |

39.353 |

4.373 |

3.817 |

21.220 |

2.863 |

80 |

.005 |

The biggest improvement was in the skills domain, and not at all in the dispositions. It means that we are able to partially respond positively to the first research question (Q1: Is there an improvement of CT self-assessment results after the implementation of CT blended apprenticeships for all students from all three classes considered together?). As can be seen from the table above, the main significant changes were in skills, both in the main categories (interpretation and explanation), subcategories (clarifying meaning, assessing claim, stating results, justifying procedures, presenting arguments) and total CrT score. This is mainly due to the fact that in each course the students had the opportunity to deal with different real-life cases in addition to theoretical information, especially due the participation of representatives from the labour market. Thus, they improved their interpretation skill (t=3.763, p=0.000) and assessing claim, subcategory of evaluation skill (t=2.036, p=0.045) because during the courses students had to interpret a range of data and information according to the topics covered, researching and evaluating each decision option. Students also had to present their final decision on a particular situation/case study and briefly justify the final results and the arguments that led to their choice (improvements in explanation skills, t=4.217, p=0.000).

Being a complex psychological phenomenon, critical thinking is hard to be explained how is improved by one or another method or teaching approach. The classes followed an inquiry-based, constructivist approach, with an increased number of teaching methods and case studies, things specific to labour market pedagogical approaches. We were targeting all skills and dispositions, but it appears that only some improved. However, we can say that a class designed together with labour market, which teaches explicitly critical thinking will have a statistically significant result on critical thinking skills, combined, as showed by the result of the total CrT score (t=2.863, p=0.005).

Regarding dispositions, no significant result was obtained. We assume that there was insufficient time to have a significant impact on something that is like a personality trait. The Aristotle’s critical spirit (and we believe this is the case of the dispositions) necessitates a significant effort over an extended period of time to be cultivated.

The results of the global analysis for all components are presented in

Appendix A.

We have tested the assumption that the groups are not equal in terms of CT skills and dispositions, assumption that led to formulate research questions 2, 3 and 4.

The analysis of the three pilot courses reveals notable variances in the initial scores of students across the distinct courses in terms of the “Interpretation” skill and the “Perseverance” disposition. In either scenario, the Bonferroni post-hoc test affirms the existence of differences between the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course and the Virtual Learning Environments in Economics course [

45]. Moreover, in both instances, students engaged in the Virtual Learning course exhibit higher average scores in “Interpretation” (14.35 vs. 12.67) and “Perseverance” (6.00 vs. 5.20) compared to students enrolled in the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course.

The GLM-Univariate ANCOVA test was utilized to evaluate the progress in three pilot courses: Business Communication (n=31), Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting (n=32), and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics (n=18). However, caution is warranted in interpreting the observed differences, as the assumption of no prior differences among the groups in the covariate was not met for the “Interpretation” skill and the “Perseverance” disposition, as discussed earlier [

45].

In general, there were no notable differences in the gains related to critical thinking (CT) skills resulting from the interventions across the three pilot courses. Yet, when examining the integrated score of CT dispositions, there was a significance (p=.017) favouring higher scores for students in Business Communication and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics (32.45±4.613 and 32.25±3.78, respectively) compared to those in the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course (29.38±4.34).

Regarding the improvements in dispositions, variations between the courses were evident in several aspects:

- Attentiveness: Differences were observed (p=.028), with Business Communication students showing greater gains compared to Virtual Learning Environments in Economics or Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting students (4.45±1.31 vs. 3.73+1.21 vs. 3.89±1.38, respectively).

- Open-Mindedness: Differences were noted (p=.047), with Business Communication and Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting students displaying higher gains than Virtual Learning Environments in Economics students (5.14±1.40 and 5.22±1.30 vs. 4.47±1.33).

- Intrinsic Goal Motivation: A significant difference was observed (p=.009), where Business Communication and Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting students exhibited greater gains (5.92±1.02 and 5.75±.76) compared to Virtual Learning Environments in Economics students (5.11±.91).

In summary, the application of the GLM-Univariate ANCOVA test revealed no substantial discrepancies in the gains of critical thinking skills among the three pilot courses. However, differences emerged in the integrated scores of CT dispositions, highlighting higher scores in Business Communication and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics. Noteworthy variations were also observed in specific dispositions, including “Attentiveness,” “Open-Mindedness,” and “Intrinsic Goal Motivation,” across the different courses.

We shall proceed to search data for the research questions 2, 3 and 4.

With regard to the analysis of each individual course, the main significant scores, following statistical analysis and interpretation of the data obtained, were observed in both categories: skills and dispositions (

Table 2). All the results obtained after applying the Paired Sample T-Test at the level of each course are presented in

Appendix B. Hence, also can respond only partially positively to all research questions, since there were statistically significant changes in skills but not in dispositions, to all three courses, with the exception of Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting which had significant differenced before and after the intervention on Open-mindedness (t=28.525, p=0.008) and on total dispositions score (t=22.090, p=0.035).

Table 2.

Skills and dispositions developed by students in each experimental course – Paired Sample T-Test.

Table 2.

Skills and dispositions developed by students in each experimental course – Paired Sample T-Test.

| Skills/dispositions |

Paired Samples T-Test |

| Statistic |

df |

p |

| Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting |

| Clarifying meaning_T1 |

Clarifying meaning_T2 |

-32.059 |

31.0 |

0.003 |

| Stating results_T1 |

Stating results_T2 |

-48.237 |

31.0 |

< .001 |

| Presenting arguments_T1 |

Presenting arguments_T2 |

-26.692 |

31.0 |

0.012 |

| Interpretation_T1 |

Interpretation_T2 |

-31.977 |

31.0 |

0.003 |

| Explanation_T1 |

Explanation_T2 |

-35.008 |

31.0 |

0.001 |

| Open-mindedness_T1 |

Open-mindedness_T2 |

28.525 |

31.0 |

0.008 |

| CrT Skills total score_T1 |

CrT Skills total score_T2 |

-23.154 |

31.0 |

0.027 |

| CrT Dispositions total score_T1 |

CrT Dispositions total score_T2 |

22.090 |

31.0 |

0.035 |

| Virtual Learning Environments in Economics |

| Analysing arguments_T1 |

Analysing arguments_T2 |

-60.592 |

17.0 |

< .001 |

| Business Communication |

| Clarifying meaning_T1 |

Clarifying meaning_T2 |

-26.859 |

30.0 |

0.012 |

| Justifying procedures_T1 |

Justifying procedures_T2 |

-25.403 |

30.0 |

0.016 |

| Presenting arguments_T1 |

Presenting arguments_T2 |

-25.086 |

30.0 |

0.018 |

| Interpretation_T1 |

Interpretation_T2 |

-23.039 |

30.0 |

0.028 |

| Explanation_T1 |

Explanation_T1 |

-23.360 |

30.0 |

0.026 |

Regarding the previously formulated research questions, as the results show, the intervention of the instructors in the labour market and changing teaching approach contributed to the development and improvement of critical thinking skills among the students: improved results were registered at the level of interpretation and explanation skills, with related subcategories, as well as at the level of the subcategory analysing arguments characteristic of the evaluation skill. Significant changes were also obtained for the open-mindedness disposition.

This is mainly because labour market organizations use a range of textbooks, practical exercises, case studies, platforms, websites that can be accessed by learners compared to higher education institutions. Thus, participants have the opportunity to learn everything through e-learning games/sessions/tutorials [

47]. Also, during the interventions, trainers from labour market organisations used different interactive images, short videos adapted, of course, to the topics addressed in each course. As a result, the students’ interpretation and explanation skills improved significantly.

At the level of

Pedagogy and didactics of financial accounting course, students were put by the trainers in different practical situations. One learning scenario addressed by the trainers consisted of presenting a training session in which the students were participants, and in the next meeting they acted from the teacher’s perspective. Students had an interactive instrument in Google Drive which facilitated

metacognition, interpretation, and explanation. Students were asked to start from content they remember and then to recall how the trainer acted in that moment, how the strategy looked. How was that moment a valid educational experience? After the metacognitive stage, the HE teacher named teaching methods and strategies in order to

clarify the meaning of the trainer’s pedagogical actions. This step was necessary for obtaining awareness and enhancing

open-mindedness. The latter was also developed in the classes held exclusively by the HE teacher. Students had to create multiple didactical scenarios for the same set of operational objectives, using different methods, strategies, environment and materials. Open-mindedness was monitored by the teacher using

systematic observation ranking sheets [

48]. The HE teacher and LMO trainer continuous provided valuable input to the students, who were able to learn how to select the information needed to teach a lesson specific to Economics subjects, taking into account the school curriculum, and thus significant results were achieved in improving interpretation and explanation skills. A great deal was invested in open-mindedness, with metacognition as driving tool. The higher education teacher monitored through observational sheets the progress of the students.

Overall skills scores increase. We can assume that an inquiry-based, constructivist approach, with an increased number of teaching methods and case studies, things specific to labour market pedagogical approaches improve critical thinking skills. But we cannot know or explain or account that a new intervention will improve the same skills. However, we can say that a class designed together with labour market, which teaches explicitly critical thinking will have a statistically significant result on critical thinking skills, combined, as showed by the result of the total CrT score (t=2.863, p=0.005).

In comparison to dispositions, skills develop faster, meaning it is feasible to propose a semester class and to tackle skills, but is increasingly problematic to aim for the dispositions in such short time.

For the second course, Virtual Learning Environments in Economics, the students were assigned to develop a virtual learning environment using various IT solutions such as Google sites and other solutions for a discipline chosen by them. Considering the theoretical information transmitted, through the use of best practice examples and case studies, students have developed various interactive platforms that will ensure the best conditions for educational activities in the virtual environment [

46]. The entire process of creating interactive learning solutions in the virtual environment created by the students was permanently monitored and moderated by the teacher. From the stage of designing the IT solution, establishing the objectives and the methods by which the content will be transmitted, designing and writing the content and up to the implementation of the interactive solutions created by the students, the teacher analysed their evolution, discussed with the students and showed them the best ways to maximize the effectiveness of the interactive learning solutions in the virtual environment created. At the same time, they had to create different interactive presentations on various Economics topics using the Canva platform, according to the information presented by the trainers in the courses. In this way, after analyzing and researching the information, in order to determine the most important data for solving the assigned topics, the students especially developed their

analysing arguments skills (p<0.001).

In the Business Communication course students have acquired a series of theoretical information on the main types of communication (verbal, nonverbal, paraverbal) [

49]. After delivery of the information by the teachers the students interpreted the information and presented their arguments on the main advantages, disadvantages, differences/similarities of the types of communication. Another topic discussed with the students in regard to types of communication was about the mission and vision of the organizations. After the presentation of the information, the students had to

analyse and

interpret different missions and visions of well-known companies, trying to identify what information is intended to be communicated by the organization to its end-users, as well as the moods/emotions/feelings that these missions and visions create on an unconscious level in people.

They also had to analyse different business situations. A case study addressed by the labour market representatives together with the students aimed at identifying the main dysfunctions occurring in the implementation of the projects, so the students had to transpose themselves one by one, both in the role of the project team members and in the role of the project manager trying to find the best solution to improve the problematic situations. The students had to analyse each party involved in the project in order to identify the problems that had occurred and clarify the issues, and then interpret all the data obtained in order to design a successful project. In transforming a failed project into a successful one, students had to justify the main methods and procedures used and specify which activities/sub-activities would be changed/updated.

At the same time, the course addressed issues related to the main barriers encountered in the communication process in the business environment. Students had to work in teams to find the meaning of certain colours in different countries and to explain in a presentation how colours are considered by different cultures (e.g. the colour yellow represents the colour of mourning in Egypt while in Japan it represents courage etc.). After all the presentations students worked on a common presentation concluding which colours could represent a barrier in a business meeting. Also related to business meetings, students were presented by teachers, information regarding the body language, worktables, office layout, in order to promote a cooperative relationship, analysing and interpreting several situations from official international meetings.

As it is also evident from the presentation of the main themes addressed with the students throughout the Business Communication course, the students as a result of analysing and interpreting certain data/situations/case studies, as well as due to all the activities they took part in, improved their critical thinking skills, respectively the skills of explanation (p=0.001) and interpretation (p=0.003), as well as the subcategories of clarifying meaning (p=0.012), justifying procedures (p=0.016) and presenting arguments (p=0.018).

Throughout the three experimental courses, the labour market trainers used different interactive teaching methods and it was also their responsibility to arouse the students’ curiosity and get them actively involved during the sessions, directing them towards discovering the results.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, the meticulous analysis of the outcomes stemming from the comprehensive study on critical thinking has provided a multifaceted perspective on the intricacies of skill and disposition development within educational contexts. The journey traversed through the three distinct courses—Business Communication, Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting, and Virtual Learning Environments in Economics—unveiled intriguing patterns of improvement and transformation.

A recurring theme that emerged from the data is the robust nature of skill enhancement, a facet that responded more readily to the interventions. The progressive shifts within the interpretation, explanation, and evaluation skills were undeniably influenced by the dynamic blend of labour market insights and innovative teaching methods. The engagement of students in real-world scenarios, the integration of diverse learning platforms, and the facilitation of metacognitive processes collectively underscored the potency of these pedagogical strategies in honing critical thinking skills. The interactive nature of these courses, guided by labour market expertise, not only imparted theoretical knowledge but also kindled curiosity, nurturing an environment where students actively constructed their own understanding and applied their learning to practical scenarios.

While skills demonstrated notable advancements, the journey of disposition development posed distinct challenges. The intricacies of dispositions, akin to personality traits, proved more resistant to change within the relatively short timeframe of the courses. Nevertheless, the observation of variations in certain dispositions—attentiveness, open-mindedness, and intrinsic goal motivation—across different courses shed light on the nuances of disposition enhancement. It is clear that these traits, reflective of Aristotle’s critical spirit, demand a prolonged and sustained effort to cultivate. The journey to foster open-mindedness, in particular, highlights the importance of metacognition and the creation of multiple didactical scenarios, as seen in the Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting course.

The findings underscore the intrinsic value of labour market perspectives in shaping contemporary education. The infusion of real-world relevance not only kindles students’ enthusiasm but also augments their critical thinking competencies. The inquiry-based, constructivist approach employed across the courses presents a promising avenue for skill and disposition development. This approach, characterized by interactive learning, collaborative problem-solving, and experiential engagement, aligns closely with labour market pedagogical paradigms, fostering a seamless transition from academia to the professional sphere.

The study’s limitations warrant acknowledgment. The short duration of the courses limited the extent of disposition development, emphasizing the need for sustained interventions to instil lasting change in these personality traits. Additionally, the study’s focus on specific courses and contexts necessitates cautious generalization to other educational settings.

In conclusion, this comprehensive exploration illuminates the multifaceted nature of critical thinking enhancement within diverse educational contexts. The amalgamation of labour market insights, innovative pedagogical techniques, and immersive learning experiences provides a holistic framework to nurture both skills and dispositions. The journey transcends the boundaries of traditional education, embracing the transformative potential of dynamic learning environments that mirror the complexities of the real world. As we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of education, the insights garnered from this study inspire us to continually refine our pedagogical approaches, catalysing critical thinking prowess and nurturing future-ready individuals.