Submitted:

29 September 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

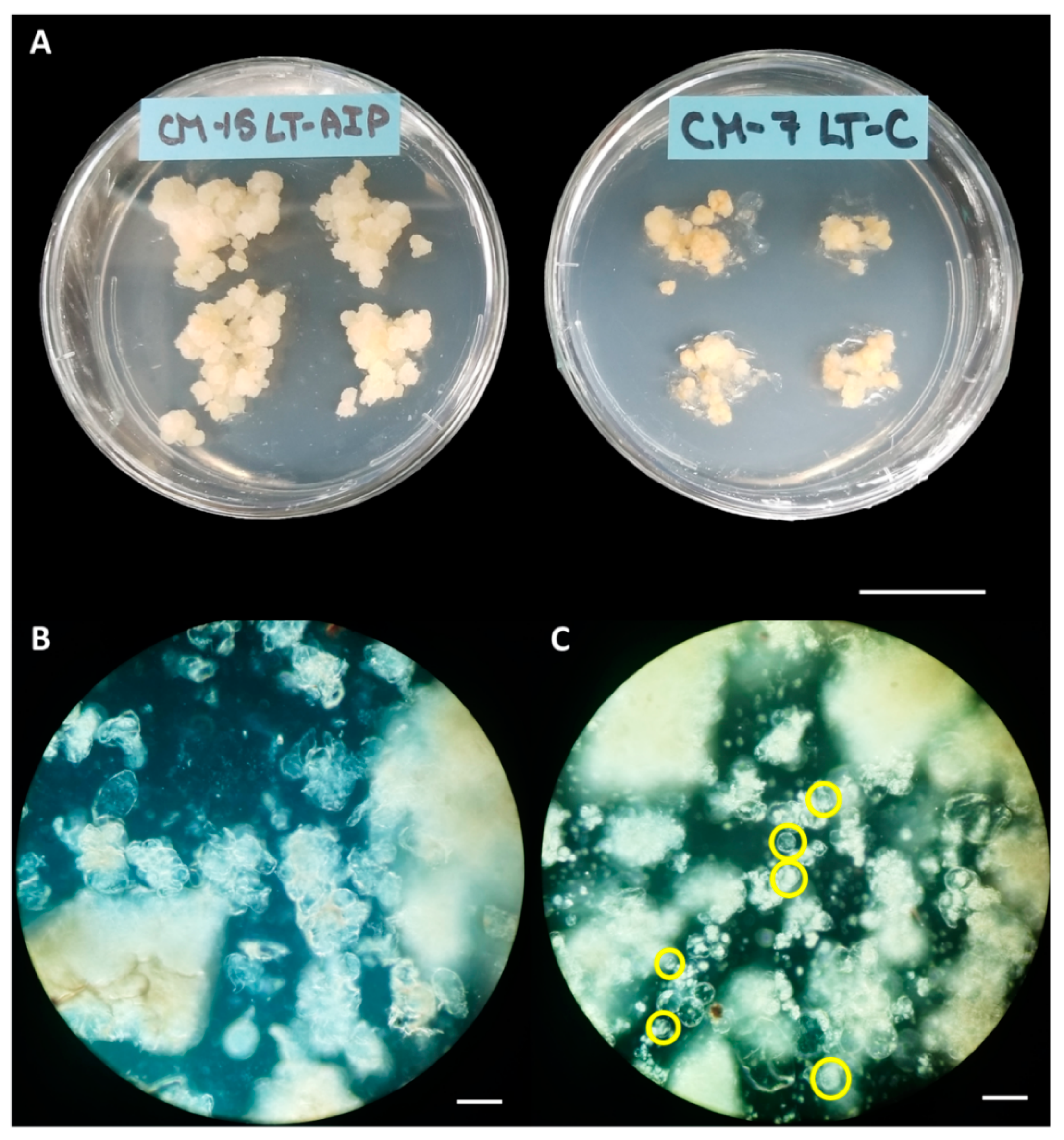

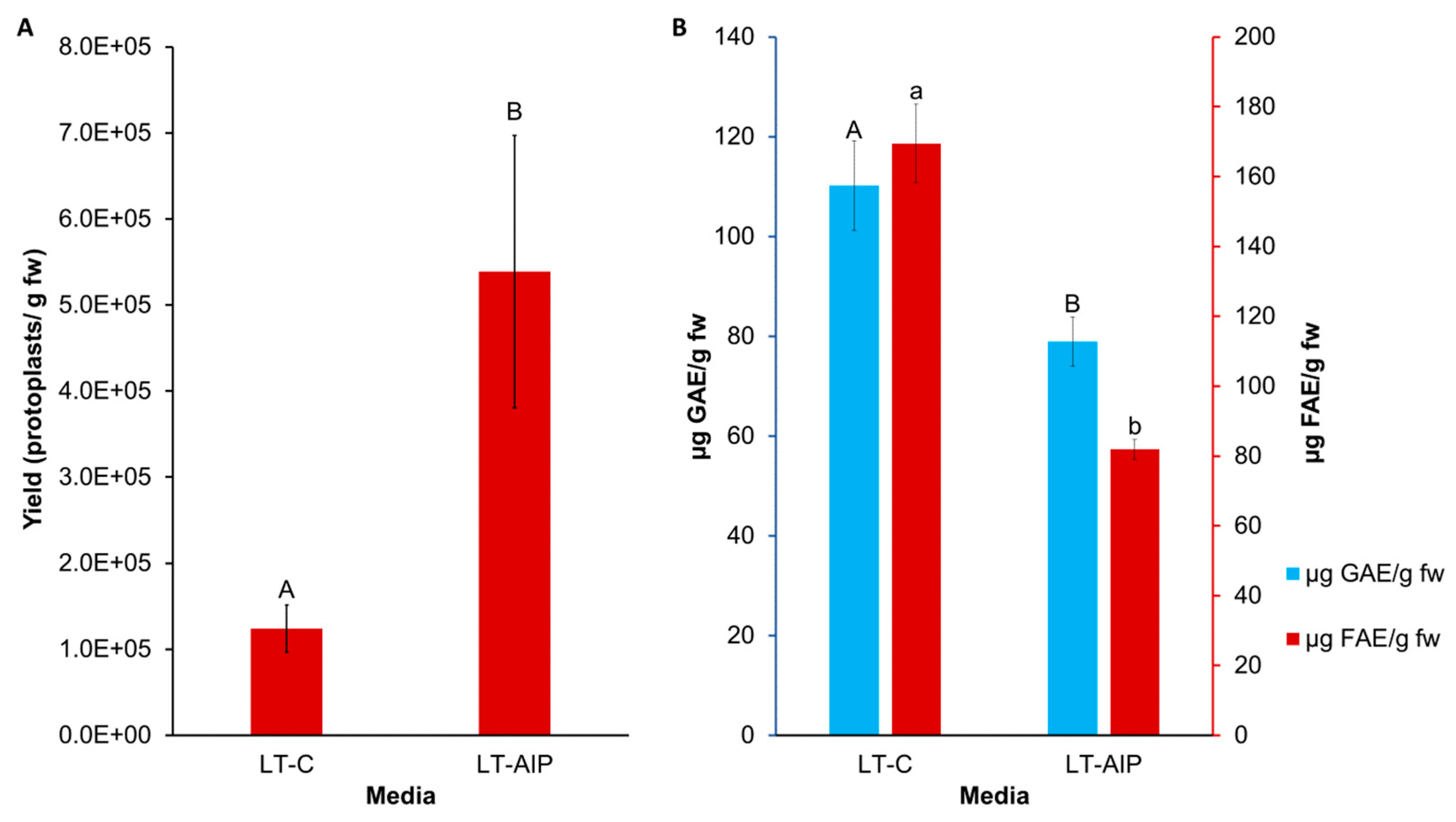

Callus Culture Initiation, Digestibility and Protoplast Yield

Total Soluble Phenolics and Tissue Browning

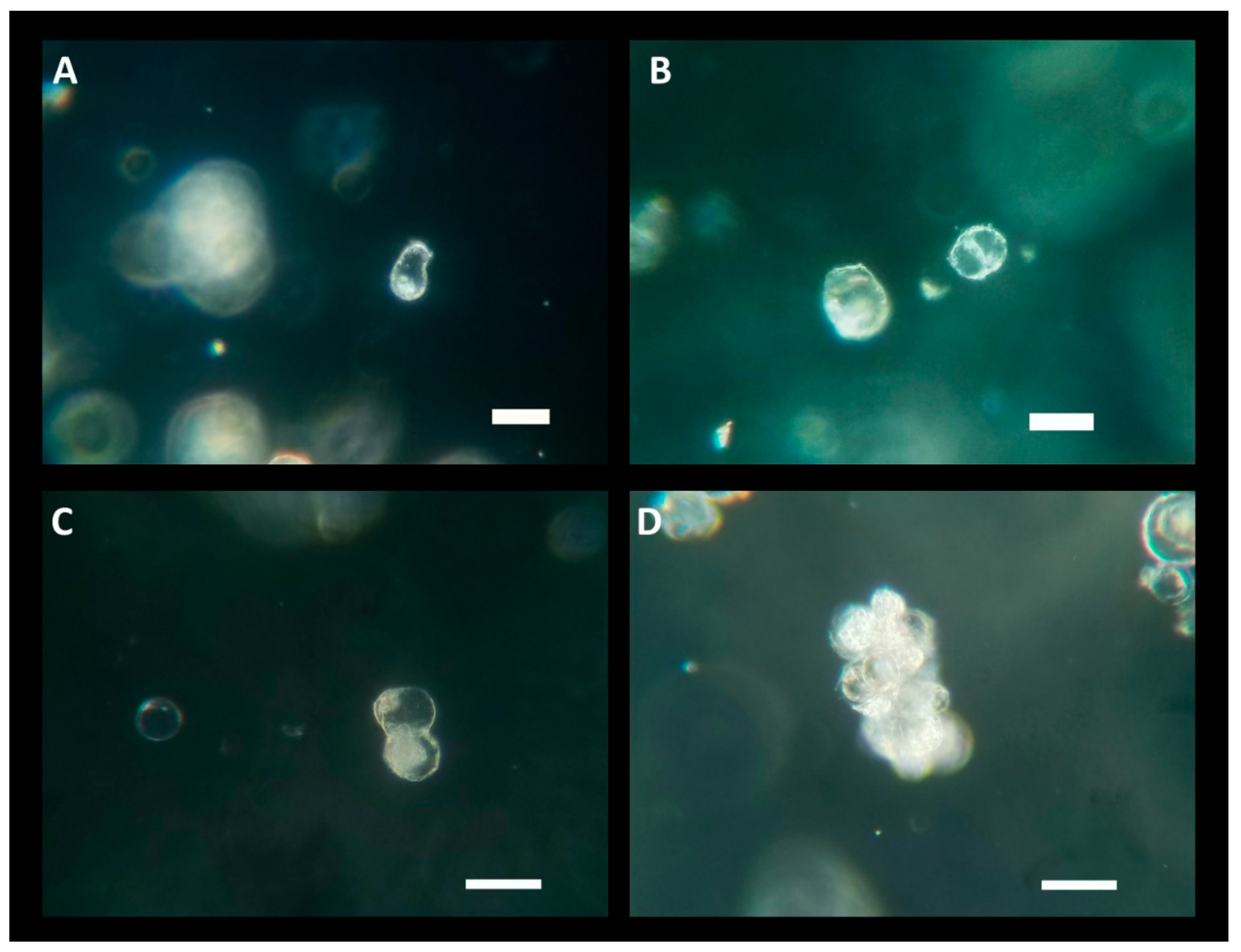

Protoplast Viability and Culture

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Callus Culture Initiation

Enzyme Preparation for Protoplast Isolation

Protoplast Digestion and Assessment

Protoplast Isolation and Culture

Total phenols and Browning Assay Extract Preparation

Total Phenols and Browning Assay

Experimental Design & Statistical Analysis

- y represented the measured response variables (protoplast yield, total soluble phenolics, and browning)

- µ denoted the overall mean of the response variable

- frequency of subculture and AIP were considered as the fixed effects

- e is the residual error

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monthony, A.S.; Page, S.R.; Hesami, M.; Jones, A.M.P. The Past, Present and Future of Cannabis sativa Tissue Culture. Plants 2021, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monthony, A.S.; Kyne, S.T.; Grainger, C.M.; Jones, A.M.P. Recalcitrance of Cannabis sativa to de novo regeneration; a multi-genotype replication study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0235525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.R.G.; Monthony, A.S.; Jones, A.M.P. DKW basal salts improve micropropagation and callogenesis compared with MS basal salts in multiple commercial cultivars of Cannabis sativa. Botany 2021, 99, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, H.; Chandra, S.; Khan, I.A.; Elsohly, M.A. Propagation through alginate encapsulation of axillary buds of Cannabis sativa L. - An important medicinal plant. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2009, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lata, H.; Chandra, S.; Techen, N.; Khan, I.A.; ElSohly, M.A. In vitro mass propagation of Cannabis sativa L.: A protocol refinement using novel aromatic cytokinin meta-topolin and the assessment of eco-physiological, biochemical and genetic fidelity of micropropagated plants. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2016, 3, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, T.; Dreger, M.; Wielgus, K.; Słomski, R. Modified nodal cuttings and shoot tips protocol for rapid regeneration of Cannabis sativa L. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbas, L.N.; Kurtz, L.E.; Lubell-Brand, J.D. A Comparison of Two Media Formulations and Two Vented Culture Vessels for Shoot Multiplication and Rooting of Hemp Shoot Tip Cultures. Horttechnology 2023, 33, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Bidwell, L.C.; Gaudino, R.; Torres, A.; Du, G.; Ruthenburg, T.C.; Decesare, K.; Land, D.P.; Hutchison, K.E.; Kane, N.C. Compromised External Validity: Federally Produced Cannabis Does Not Reflect Legal Markets. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, A.L.; McGlaughlin, M.E. Genetic tools weed out misconceptions of strain reliability in Cannabis sativa: implications for a budding industry. J. Cannabis Res. 2019, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, A.L.; Hansen, C.J.; Hyslop, R.M.; McGlaughlin, M.E. Research grade marijuana supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse is genetically divergent from commercially available Cannabis. bioRxiv 2019, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Huscher, E.L.; Keepers, K.G.; Pisupati, R.; Schwabe, A.L.; Mcglaughlin, M.E.; Kane, N.C. Genomic evidence that governmentally produced Cannabis sativa poorly represents genetic variation available in state markets. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissinot, J.; Adamek, K.; Jones, A.M.P.; Normandeau, E.; Boyle, B.; Torkamaneh, D. Comparative Restriction Enzyme Analysis of Methylation (CREAM) Reveals Methylome Variability Within a Clonal In Vitro Cannabis Population. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesami, M.; Jones, A.M.P. Modeling and optimizing callus growth and development in Cannabis sativa using random forest and support vector machine in combination with a genetic algorithm. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, K.M.; Boling, A.W.H.; Bargmann, B.O.R. Protoplast isolation, transient transformation, and flow-cytometric analysis of reporter-gene activation in Cannabis sativa L. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 164, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K.M.; Gunn, H.; Moretti, N.; Zemetra, R.S. A streamlined protocol for wheat (Triticum aestivum) protoplast isolation and transformation with CRISPR-Cas ribonucleoprotein complexes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnoy, M.; Viola, R.; Jung, M.H.; Koo, O.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.S.; Velasco, R.; Kanchiswamy, C.N. DNA-free genetically edited grapevine and apple protoplast using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.S.; Hsu, C.T.; Yang, L.H.; Lee, L.Y.; Fu, J.Y.; Cheng, Q.W.; Wu, F.H.; Hsiao, H.C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Application of protoplast technology to CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis: from single-cell mutation detection to mutant plant regeneration. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, J.W.; Gmitter, F.G. Protoplast Fusion and Citrus Improvement. In Plant Breeding Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 339–374. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Tanaka, H.; Fukamizu, T.; Shoyama, Y.; Shoyama, Y.; Taura, F. Identification and characterization of cannabinoids that induce cell death through mitochondrial permeability transition in cannabis leaf cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20739–20751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazič, S. Isolation of Protoplasts from Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.), University of Ljubljana, 2020.

- Kim, A.L.; Yun, Y.J.; Choi, H.W.; Hong, C.H.; Shim, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.C. Establishment of efficient Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) protoplast isolation and transient expression condition. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 16, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhao, Y.; You, X.; Zhang, Y.J.; Vasseur, L.; Haughn, G.; Liu, Y. A versatile protoplast system and its application in Cannabis sativa L. Botany 2023, 101, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Ávila, A.; García-Fortea, E.; Prohens, J.; Herraiz, F.J. Development of a Direct in vitro Plant Regeneration Protocol From Cannabis sativa L. Seedling Explants: Developmental Morphology of Shoot Regeneration and Ploidy Level of Regenerated Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, G.; Cheng, C.; Lei, L.; Sun, J.; Xu, Y.; Deng, C.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Establishment of an Agrobacterium -mediated genetic transformation and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Hemp ( Cannabis Sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.K.; Chapple, C. The origin and evolution of lignin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2010, 187, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chantreau, M.; Sibout, R.; Hawkins, S. Plant cell wall lignification and monolignol metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornalé, S.; Rencoret, J.; García-Calvo, L.; Encina, A.; Rigau, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; del Río, J.C.; Caparros-Ruiz, D. Changes In Cell Wall Polymers And Degradability In Maize Mutants Lacking 3′- And 5′- O -Methyltransferases Involved In Lignin Biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, pcw198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.D. A general method for the high-yield isolation of mesophyll protoplasts from deciduous tree species. Plant Sci. 1985, 42, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.P.; Shukla, M.R.; Biswas, G.C.G.; Saxena, P.K. Protoplast-to-plant regeneration of American elm (Ulmus americana). Protoplasma 2015, 252, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.P.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Shukla, M.; Zoń, J.; Saxena, P.K. Inhibition of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis increases cell wall digestibility, protoplast isolation, and facilitates sustained cell division in American elm (Ulmus americana). BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.P.; Saxena, P.K. Inhibition of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L.: A novel approach to reduce oxidative browning in plant tissue culture. PLoS One 2013, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.D.; Karnosky, D.F. Techniques for high-frequency isolation of elm protoplasts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Northeastern Forest Tree Improvement Conference; 1981; pp. 213–222.

- Redenbaugh, K.; Karnosky, D.F.; Westfall, R.D. Protoplast isolation and fusion in three Ulmus species. Can. J. Bot. 1981, 59, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, H.; Chandra, S.; Khan, I.A.; Elsohly, M.A. High Frequency Plant Regeneration from Leaf Derived Callus of High Δ 9 -Tetrahydrocannabinol Yielding Cannabis sativa L. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-D.; Cho, Y.-H.; Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1565–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, K.N.; Michayluk, M.R. Nutritional requirements for growth of Vicia hajastana cells and protoplasts at a very low population density in liquid media. Planta 1975, 126, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. In Methods; 1999; Vol. 299, pp. 152–178.

- Kupina, S.; Fields, C.; Roman, M.C.; Brunelle, S.L. Determination of total phenolic content using the Folin-C assay: Single-laboratory validation, first action 2017.13. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, B.O.R.; Birnbaum, K.D. Positive fluorescent selection permits precise, rapid, and in-depth overexpression analysis in plant protoplasts. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaohua, C.; Gonggu, Z.; Lining, Z.; Chunsheng, G.; Qing, T.; Jianhua, C.; Xinbo, G.; Dingxiang, P.; Jianguang, S. A rapid shoot regeneration protocol from the cotyledons of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiser, G.; López-Gálvez, G.; Cantwell, M.; Saltveit, M.E. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase inhibitors control browning of cut lettuce. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1998, 14, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, C.D.; Zoń, J.; Jones, A.M.P. Improving callus regeneration of Miscanthus × giganteus J.M.Greef, Deuter ex Hodk., Renvoize ‘M161′ callus by inhibition of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. - Plant 2019, 55, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, G.E.; Lewers, K.S.; Medina, M.B.; Saftner, R.A. Comparative analysis of strawberry total phenolics via Fast Blue BB vs. Folin-Ciocalteu: Assay interference by ascorbic acid. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 27, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lörz, H.; Larkin, P.J.; Thomson, J.; Scowcroft, W.R. Improved protoplast culture and agarose media. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 1983, 2, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schween, G.; Hohe, A.; Koprivova, A.; Reski, R. Effects of nutrients, cell density and culture techniques on protoplast regeneration and early protonema development in a moss,Physcomitrella patens. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khentry, Y.; Paradornuvat, A.; Tantiwiwat, S.; Phansiri, S.; Thaveechai, N. Protoplast isolation and culture of Dendrobium Sonia “Bom 17. ” Kasetsart J. - Nat. Sci. 2006, 40, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

| Media | Yield (protoplasts/g fw) | Viability (%) |

|---|---|---|

| LT-C | 2.87×104 ± 1.10×104 | 95.5 ± 2.6 |

| LT-AIP | 8.78×104 ± 3.9×104 | 92.1 ± 5.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).