Introduction

Emerging adulthood is a newly recognized concept in the study of the life span, encompassing the period from the end of adolescence to the early stages of adulthood. This age range typically spans from 18 to 25 years old (Arnett & Mitra, 2020) and is characterized by identity exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between, and possibilities (Murray & Arnett, 2020). It is rare for someone not to be involved in intimate relationships with others during emerging adulthood. Multiple relationships, transient in nature, lacking commitment and intimacy, or difficulty initiating and maintaining long-lasting and meaningful relationships are prevalent during this stage. Therefore, relationship engagement can be considered a pivotal aspect of emerging adulthood (Shulman et al., 2014). Erik Erikson's (1968) psychosocial development theory proposes that the crisis of emerging adulthood is conceptualized as intimacy versus isolation. At this stage, individuals strive to establish intimate relationships with others. Successfully resolving this crisis can lead to the creation of satisfying relationships characterized by commitment, security, and care. Conversely, avoiding intimacy, fear of commitment, and relationships can lead to isolation and loneliness. Ratelle et al. (2013) believed that after the childhood period, during which relationships with parents hold particular importance, the role of friends as a supportive resource in emotional challenges increases during adolescence and emerging adulthood. It is during this time that the quantity and quality of friendships assist individuals in overcoming academic and personal challenges and facilitate their well-being.

Relationship well-being refers to the establishment of warm, empathetic, and intimate relationships accompanied by commitment, satisfaction, vitality, and trust (Gaine & La Guardia, 2009; Matud et al., 2022). Low levels of relationship well-being with friends during emerging adulthood have been associated with depression (Kopala-Sibley et al., 2012), loneliness (Doumen et al., 2012), and low self-esteem (Özabacı & Eryılmaz, 2015). On the other hand, high-quality interpersonal relationships at this age are accompanied by happiness (Demir, 2010), hope (Booker et al., 2021), and life satisfaction (Crocetti & Meeus, 2014).

One of the contemporary theories that has been able to address well-being from an organismic, contextual, and motivational perspective and examine the role of basic psychological needs is Self-determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2020). This theory refers to the eudemonistic approach in investigating well-being, contrasting hedonistic views that consider increasing pleasure and reducing pain as the essence of well-being, emphasizing happiness and the pursuit of it. In contrast, the eudemonistic approach focuses on the realization of personal goals, striving for excellence, and the actualization of individual potential (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Self-determination theory (SDT) assumes that human beings have an inherent motivation for growth and actualization. When individuals are intrinsically motivated, they autonomously move towards experiencing new challenges. This theory aims to understand why individuals engage in various activities (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Self-determination theory (SDT) encompasses several sub-theories. According to the Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), intrinsic motivation is influenced by supportive environments and contexts. Thus, in addition to interactions with parents during childhood (Grolnick, 2009), educational (Sjöblom et al., 2016) and occupational (Van den Broeck et al., 2016) settings can play a role in fostering and nurturing intrinsic motivation in individuals. The impact of environments on intrinsic motivation and individual well-being occurs through basic psychological needs satisfaction. Based on the Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT), intrinsic motivation and individual well-being are associated with the satisfaction of three inherent and universal needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2021). Autonomy refers to an individual's basic inclination towards being the cause or agent of their actions: competence involves the perception of mastery over actions and the achievement of goals, and relatedness indicates that inherent exploratory behavior in all humans becomes potentiated when individuals act based on a sense of basic security or connectedness. Family, friends, educational, and occupational contexts, by providing a supportive environment for fulfilling basic psychological needs, can contribute to positive individual development (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Furthermore, the lack of interpersonal need satisfaction can have seriously affect individuals' well-being. In this regard, the Interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (IPTS) considers perceived burdensomeness as the individual's perception of being a burden to others, lacking contribution to the welfare and well-being of the group, and thwarted belongingness as the sense of lacking connection with others and experiencing the weakening or loss of previously meaningful relationships (Joiner, 2005). Suicidal tendencies arise from unmet needs for relatedness and competence, as well as perceived burdensomeness (Batterham & Calear, 2021). Research indicates that basic psychological needs satisfaction is positively associated with happiness (Ren & Jiang, 2021; Bahraei et al., 2022), vitality (Carmignola et al., 2021), positive relationships with others (Koh et al., 2012), relationship quality (Philippe et al., 2013), subjective well-being (Wang et al., 2017), and negatively associated with stress and social deprivation (Koh et al., 2012) and depression (Wang et al., 2017).

According to the Goal Contents Theory (GCT), individuals who base their life goals on intrinsic orientation, emphasizing relatedness, personal growth, meaningful relationships, and social contributions, will experience positive psychological outcomes (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). In the context of friendships, compassionate and self-image goals are introduced (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). Compassionate goals involve supporting others unconditionally, including overlooking the mistakes of others, striving for positive change in their lives, and avoiding selfishness in interactions. Self-image goals encompass planning, effort, and focus on gaining attention and approval from others, seeking validation and affirmation. Intrinsic goals (compassionate goals) are associated with high well-being, while extrinsic goals (self-image goals) are associated with lower well-being (Hope et al., 2019).

According to the Organismic Integration Theory (OIT), the inclination for autonomous motivation gradually shifts during internalization from external regulation to introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation, ultimately leading to self-regulation. Initially, behavior regulation is based on external standards and others' judgments, but through internalization, personal standards become the basis for regulating behavior. The process of internalization is strengthened by the need for competence and relatedness. Thus, the basic psychological needs satisfaction leads to self-regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Finally, the Relationships Motivation Theory (RMT) suggests that the satisfaction of relatedness internally motivates individuals to establish close and voluntary relationships, fostering satisfaction and well-being in relationships. According to this sub-theory, the satisfaction of all three psychological needs in the context of relationships contributes to well-being and relationship satisfaction, provided that social support (from family, friends, spouse, etc.) is sufficient for self-regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Overall, according to the self-determination theory (SDT), perceiving well-being in relationships is contingent upon supportive contexts, intrinsic goals for the relationship, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and self-regulation in relationships. Individuals experience satisfaction, happiness, and intrinsic enjoyment in their relationships when the surrounding context facilitates the satisfaction of their basic needs, allowing them to set intrinsic goals for the relationship and autonomously regulate their behaviors. The literature indicates that the roles of these constructs have been explored more extensively in educational and occupational contexts, as well as concerning parents and teachers, rather than in the context of friendships during emerging adulthood. Additionally, the role of individuals' supportive behaviors in meeting the basic psychological needs of others in friendships, their impact on the individual's need satisfaction, and the implications for individuals' well-being have received less attention. Rocchi et al. (2017) in their study demonstrated that individuals' support or thwarting of others' psychological needs is related to the satisfaction or frustration of their own basic psychological needs in relationships. In other words, when individuals create an environment in their relationships that facilitates the satisfaction of others' basic psychological needs, it, in turn, contributes to the satisfaction of their own basic psychological needs.

As mentioned earlier, intimate relationships, especially friendships, pose significant challenges during emerging adulthood. The university environment plays a crucial role in the formation and strengthening of intimate relationships. Entering university is a universal occurrence during emerging adulthood and is a sensitive and influential period in individuals' lives (Dolatshahee et al., 2016). This transition is also significant in terms of interpersonal relationships. On the one hand, it encompasses the first years of independent living away from family, on the other hand, it distances individuals from the intimate relationships of adolescence with friends and introduces them to diverse, more independent, and sometimes unstable and temporary relationships such as roommate relationships, classmates, professors, student organizations, and so on. If intimacy, commitment, trust, and satisfaction are not fostered in these relationships, it can lead to feelings of loneliness and isolation (Tett et al., 2017).

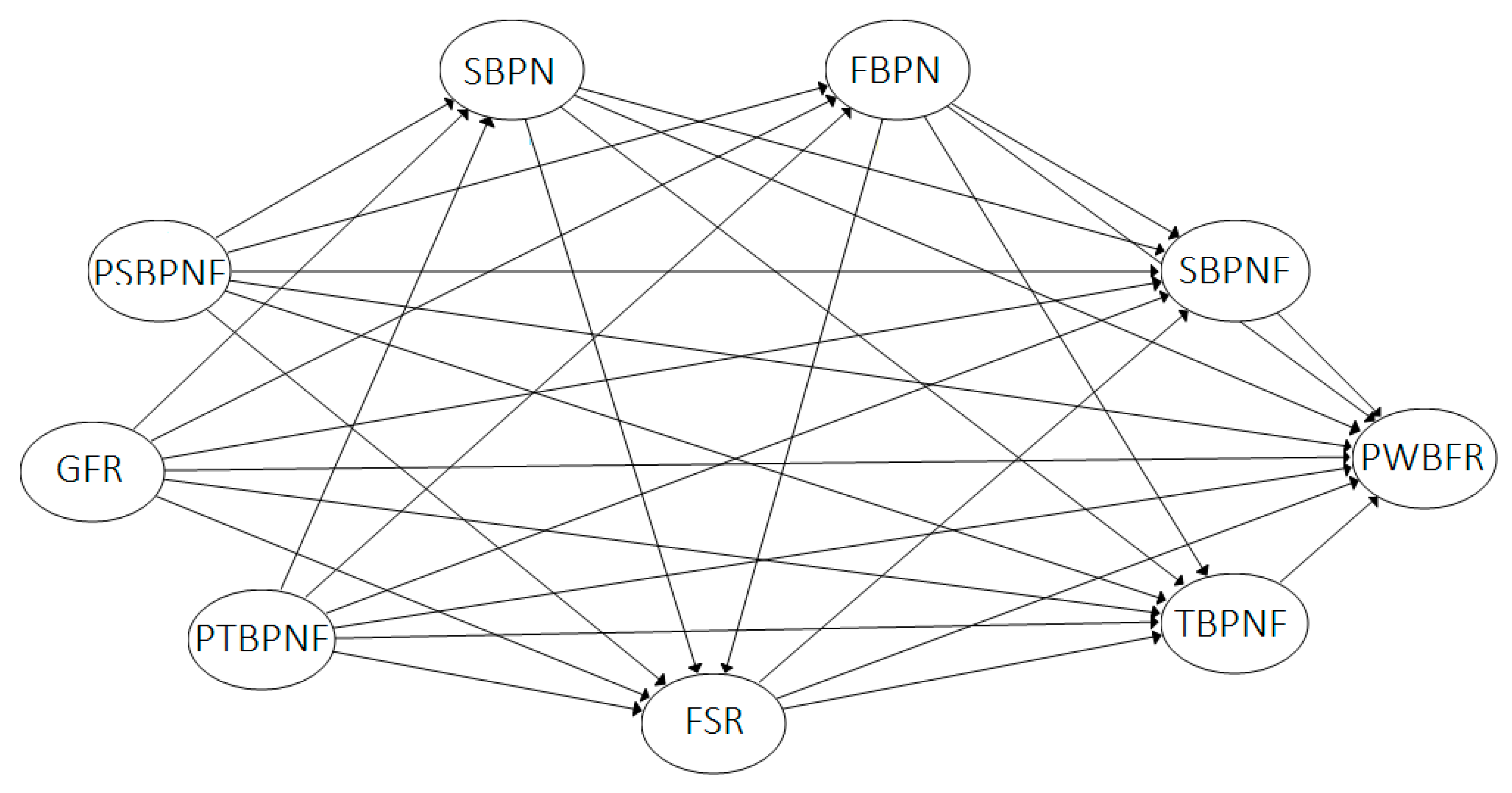

Overall, self-determination theory (SDT) can be utilized as a theoretical framework to describe and explain the perceived well-being in friendship relationships. However, further investigation is needed to examine the mechanisms of context, goals, satisfaction or frustration of basic psychological needs, self-regulation, and individual' behaviors in this domain. It seems that these relationships, as discussed within the framework of self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2020), are of a multidimensional, and certain variables, such as self-regulation, play a mediating role in this context. Therefore, considering the limited research, particularly in Persian culture, on friendships during emerging adulthood from motivational perspectives such as self-determination theory (SDT), the present study aimed to use structural equation modeling to determine the role of the perceived support/thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends and the goals in friendship relationships, with perceived well-being in friendship relationships, with the mediating role of satisfied/ frustrated basic psychological needs, friendship self-regulation, and supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends (

Figure 1).

Method

Participants

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to identify the critical determinants of perceived well-being in friendships. Hair et al. (2021) believed that PLS-SEM is more suitable when the study aims to explore complex relationships within a theoretical framework, especially when the structural model is complex with numerous constructs and indicators. The research population consisted of undergraduate students at the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad. In determining the sample size, Hair et al, (2021), they have believed that in PLS-SEM, the minimum sample size should be ten times the maximum number of indicators related to the constructs in the model (i.e., the construct with the most indicators) or ten times the number of paths that lead to the dependent construct in the model. However, increasing the sample size enhances the accuracy and validity of the model estimates. Based on Tabachnick and Fidell (2019), the formula n=20(X)+150 used, where “x” represents the number of observed variables, and 150 accounts for the number of individuals to consider the likelihood of sample attrition (due to the electronic data collection method). Accordingly, a sample size of 730 individuals considered. Sampling conducted using the convenience method. Initially, four academic groups (humanities, sciences, engineering and technology, agriculture, and arts) were selected. Data collection continued until the desired sample size reached. Finally, after excluding incomplete questionnaires, the data of 726 individuals were analyzed.

Demographic indicators revealed that the mean age was 20.32 (SD=1.67, ranging from 18 to 25 years). Female participants constituted 68.2% of the sample, and 93.7% were single. The distribution of the sample by field of study showed that 35% of the students were in the humanities, 28.9% in the basic sciences, 30% in the technical and engineering fields, and 1.5% in agriculture, veterinary medicine, and art.

Instruments

Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire (IBQ; Rocchi et al., 2017): The Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire (IBQ) used to assess the perceived support/thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends. This questionnaire consists of 24 items measuring six subscales: autonomy support, autonomy thwarting, competence support, competence thwarting, relatedness support, and relatedness thwarting, and answered on 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Rocchi et al. (2017), after questionnaire development, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses conducted to establish the factorial validity, as well as convergent and discriminant validity, of the scale concerning to the measure of perceived satisfaction of psychological needs in friendships. In the current study, confirmatory factor analysis performed to examine the validity. The results indicated a good fit for the six-factor structure (χ2/df=2.45; GFI=.90; CFI=.95; NFI=.92; RMSEA=.07). The Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients for the subscales ranged from .89 to .95, demonstrating high internal consistency.

Compassionate and Self-image Goals Scale (CSIGS; Crocker & Canevello, 2008): This scale, developed consists of 13 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all to 5= always), measuring both Compassionate and self-image goals. In the study of Crocker and Canevello (2008), exploratory factor analysis conducted, confirming the two-factor structure. They reported Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients of .83 for compassionate goals and .90 for self-image goals. In this study, confirmatory factor analysis performed to examine validity. Results showed a good fit for the two-factor structure (χ2/df=1.41; GFI=.95; CFI=.98; NFI=.93; RMSEA=.04). The Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients for compassionate and self-image goals were obtained as .87 and .85, respectively.

Basic Need Satisfaction in Relationships Scale (BNS-RS; La Guardia et al., 2000): The Basic Need Satisfaction in Relationships Scale (BNS-RS) assessed the satisfied basic psychological needs in friendship relationships. This scale measures autonomy, competence, and relatedness with nine items that answered in a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true for me to 7 = very true for me). The reported Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients for this scale range from .85 to .94 (Langdon et al., 2018). In a study conducted among Iranian students, Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2023) examined the psychometric properties of this scale. They reported exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, confirming the desirable three-factor structure. They also examined the scale's reliability using Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients, ranging from .68 to .83. In the present study, these coefficients ranged from .80 to .89.

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ-10; Bryan., 2011): The 10-item Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ-10) was used to measure frustrated basic psychological needs in friendship relationships. This questionnaire consists of 10 items and measures the perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. All items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1= not at all true for me to 7= very true for me). The factorial validity of this questionnaire confirmed. Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients reported in various studies range from .82 to .94 (Ordoñez-Carrasco et al., 2018). In the study of Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2021), confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses supported a two-factor structure. They reported Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients of .93 for perceived burdensomeness and .87 for thwarted belongingness. In the present study, these coefficients were obtained as .81 and .83, respectively.

Friendship Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-F; Ryan & Connell, 1989): The Friendship Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-F) was used to measure friendship self-regulation. It consists of 20 items that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1= not at all true to 7= very true). The items measure four subscales: external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and intrinsic motivation. Shea et al. (2013) reported a Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient of .87 for this questionnaire. Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2021), confirmed a four-factor structure through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. They reported Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients ranging from .84 to .86. In the present study, these coefficients ranged from .72 to .78.

Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire-Self (IBQ-self; Rocchi et al., 2017): The Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire-Self (IBQ-self) used to measure a person's supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. This questionnaire consists of 24 items measuring six subscales: autonomy support, autonomy thwarting, competence support, competence thwarting, relatedness support, and relatedness thwarting, and answered in a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Rocchi et al. (2017) examined and confirmed the factorial, convergent, and divergent validity in connection with the Basic Psychological Needs Scale in Relationships. In this study, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire assessed in the context of friendships. Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated a good fit for the six-factor structure (χ2/df=2.03; GFI=.90; CFI=.95; NFI=.90; RMSEA=.07). Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients ranged from .83 to .91.

State Level Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS-SL; Ryan & Frederick, 1997): To measure vitality in friendship relationships, the State Level Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS-SL), was used. The original version of this scale consists of seven items that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1= not at all true to 7= completely true). Ryan and Frederick (1997) examined and confirmed the factorial validity, and a one-factor structure accounted for 70% of the variance. They also reported a Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient of .92. Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2019), confirmed the exploratory and confirmatory factorial validity of a six-item version. This structure accounted for 75.04% of the variance. The Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients were .93 and .92, respectively. In the present study, the Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient obtained as .93.

The Perceived Relationship Quality Component (PRQC; Fletcher et al., 2000): The Perceived Relationship Quality Component (PRQC) used to measure satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, and trust in friendship relationships. The responses are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1= not at all to 7= very much). Fletcher et al. (2000) confirmed the six-factor structure and reported Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients ranging from .74 to .96. In another study, Sarhadi et al. (2013) confirmed the six-factor structure and obtained a Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient of .86. In this study, the subscales of satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, and trust were used. The Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients were .97, .92, .93, and .95, respectively.

The Basic Empathy Scale (BES; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006): Empathy in friendship relationships was examined using the Basic Empathy Scale (BES). This scale measures cognitive and affective empathy with 20 items. The scoring is done on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). In the original study, the Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients were .66 for the total scale and .79 to .85 for the subscales, respectively. Jafari et al. (2017), in the assessment of psychometric properties among high school students, obtained a two-factor structure by removing three items and Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients of .74 to .85 and test-retest coefficients of .72 to .80 reported. In the present study, the affective empathy subscale used, and Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient was .84.

Procedure

Instruments were digitized using the Google Docs platform with prior authorization from the authors. The link to the instruments shared in social networks for easy access, and the participation was utterly anonymous. The research was regulated by the ethical norms in Iran and the American Psychology Association guidelines on human research. This study obtained ethical approval from the committee with code number IR.UM.REC.1399.098. In the electronic forms, explanations given to the participants about the objectives of the project, while assuring them about the confidentiality of the information, the voluntary participation in the research emphasized.

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient were used to examined the reliability and validity of the questionnaires. All statistical analyses conducted with SPSS (version 25.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) and AMOS (version 24.0; IBM SPSS, Wexford, PA).

In the following, PLS-SEM was used. PLS-SEM models involve two elements according to Hair et al. (2021): a measurement model, which assesses the association between items and variables (validity and reliability), and a structural model, which assesses the predictive capability of the variables proposed in the model. PLS-SEM analyses for the two elements conducted using SmartPLS 3.3.3 (Ringle & Wende, 2015). Reliability tested using the rho_A coefficient and composite reliability (CR), convergent validity using outer loads and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations method (HTMT) as proposed by Henseler et al. (2015). The structural model included the analysis of the explained variance, the effect size, the predictive effect size, and the magnitude and statistical significance of the coefficients for each path proposed in

Figure 1. Importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) used to determine priorities in the critical determinants of perceived well-being in friendship relationships.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Main Study Variables

Prior to statistical analysis, data screening performed, and missing values replaced with the series mean. Univariate outliers examined using box plots and adjusted based on the mean and standard deviation (M±1SD). Multivariate outliers assessed using the Mahalanobis distances. The results indicated the presence of 13 multivariate outliers in the data, which subsequently removed. Reanalysis did not reveal any further multivariate outliers, and the analyses proceeded with data from 713 participants. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix presented in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows that the dimensions of perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends, compassionate goals, satisfied basic psychological needs, intrinsic motivation, and intergrated regulation, as well as supporting the basic psychological needs of friends, have significant and positive correlations with perceived well-being in friendship relationships (

p<.01). Other results indicate that perceived thwarting of autonomy and relatedness are not significantly related to commitment and competence (

p>0.05), but other suscales are negative and significant (

p<.05). Self-images goals, external regulation, and thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends have negative and significant relationships with perceived well-being in friendship relationships (

p<.05). The relationship between perceived burdensomeness and vitality is not significant (

r=-.05). Introjected regulation has no significant relationship with satisfaction (

r=-.06), commitment (

r=.02), and trust (

r=-.07), but it has a negative and significant corelation with vitality (

r=-.08,

p<.05), intimacy (

r=-.26,

p<.01), and empathy (

r=-.18,

p<.01).

Measurement Model Statistics

The measurement models were derived from bootstrapping with 5000 samples.

Table 2 indicates that the factor loadings are more excellent than .49 for all indicators and are statistically significant (

p<.05). The internal consistency method showed appropriate reliability levels of the study predictors, with rho_A coefficients over .50, and composite reliability over .75. Convergent validity using AVE allowed the identification of the items that do not meet the criteria of outer loads of .50 or above and a Variance Inflator Factor (VIF) of 5.0 or below (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), showing poor validity and collinearity effects.

Table 2 shows that the CR>AVE criterion met. Therefore, the convergent validity of the measurement models can be confirmed. HTMT method showed that study variables included in the model had appropriate discriminant validity, with values below .86 and confidence intervals not including zero, indicating that each variable assesses a specific construct (

Table 3).

Structural Model Statistics

The significant path coefficients between latent variables examined to evaluate the fit of the structural model. Results of the primary model indicate that the direct effect from perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends to friendship self-regulation, the direct effect from perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends to frustrated psychological needs, and supporting/thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends, direct effect from goals in friendship relationships to frustrated psychological needs, and direct effect from frustrated psychological needs to supporting/thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends, are non-significant (p>0.05).

Accordingly, to improve the model fit and identify critical determinants, non-significant paths were removed, and the model was revised. The revised model shows that all path coefficients are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Results for the structural model (

Table 4) show that all direct effects have a significant effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (

p<0.05). Indirect effects revealed that perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends has significant indirect effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β=.204, [95% CI: .156, .258) by mediating the effect of satisfied/ frustrated basic psychological needs, supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. Perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends has significant indirect effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β=-.147, [95% CI: -.197, -.103) by mediating the effect of frustrated psychological needs, friendship self-regulation, and supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. The goal in friendship relationships has significant indirect effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β=.234, [95% CI:.188, .282) by mediating the effect of satisfied basic psychological needs, friendship self-regulation, and supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. Satisfied basic psychological needs have significant indirect effects to perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β=.124, [95% CI:.092, .116) by mediating the effect of friendship self-regulation and supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. Frustrated psychological needs have significant indirect effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β=-.116, [95% CI: -.158, -.082) by mediating the effect of friendship self-regulation and thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends. Friendship self-regulation has significant indirect effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships (β= .023, [95% CI: .01, .039) by mediating the effect of supporting/ thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends.

Table 4 demonstrates that perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends, frustrated psychological needs, and thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends have adverse effects. In contrast, the other constructs have positive effects on perceived well-being in friendship relationships.

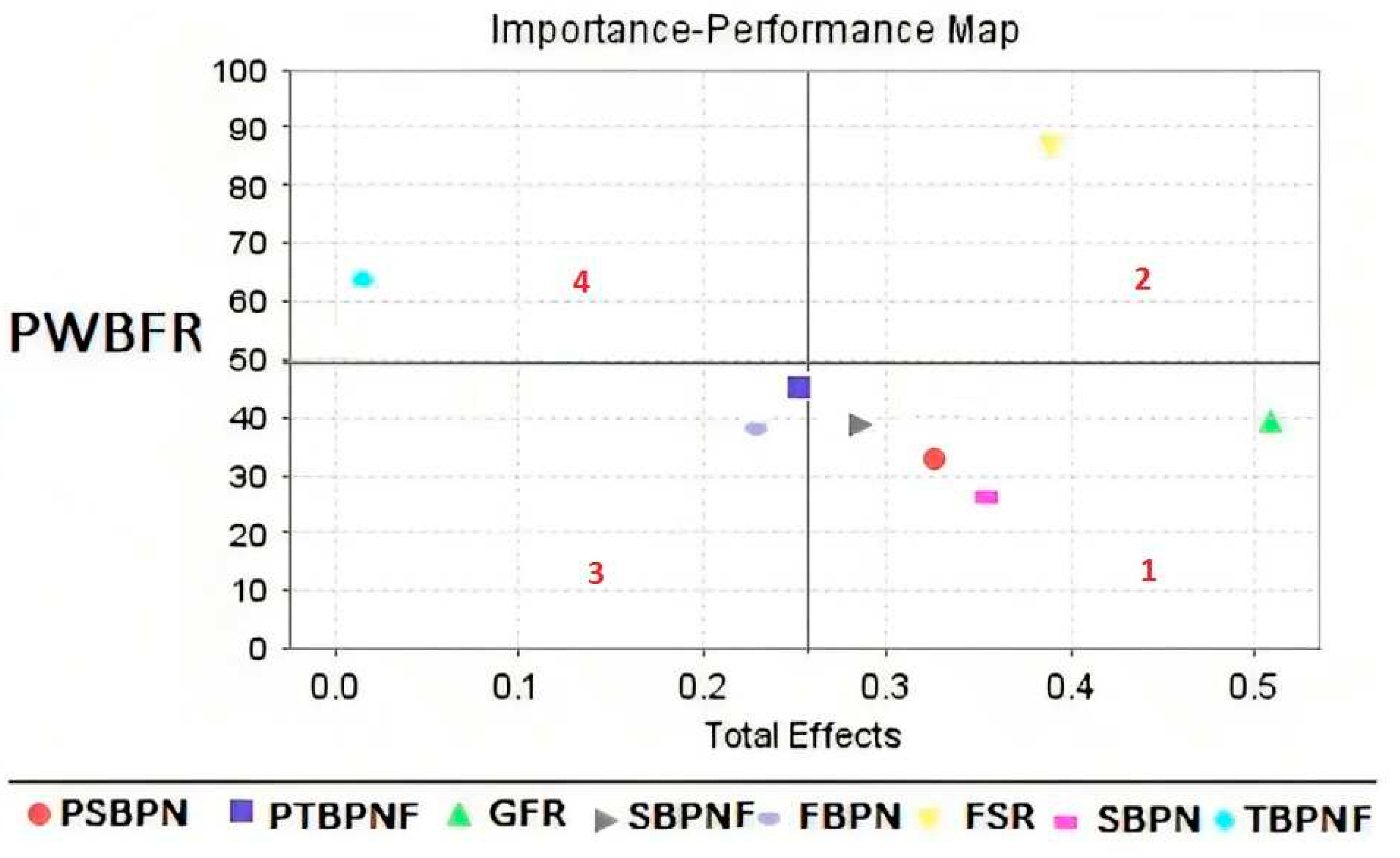

To identify the critical determinants of perceived well-being in friendship relationships, importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) conducted. This analysis identifies constructs that has high importance and low performance, indicating areas that require intervention. The results (

Table 4) showed that goals in friendship relationships have the highest importance, and perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends has the lowest importance (.458 vs. -.001). The constructs with the highest and lowest performance are friendship self-regulation and frustrated psychological needs (174.268 vs. 41.032). The importance-performance map presented in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that goals in friendship relationships, satisfying basic psychological needs, perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends, and supporting the basic psychological needs of friends have the highest importance and lowest performance (First quadrant). Friendship self-regulation is in the second quadrant (high importance, high performance). The examination of the third quadrant (low importance, low performance) reveals that perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends and frustrated psychological needs included. Finally, in the fourth quadrant (low importance, high performance), thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends is situated.

Discussion

In this study, the direct, and indirect effects of predictor variables on perceived well-being in friendship relationships in friendships examined with the aim to identify the critical determinants accurately. The results demonstrated that perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends has a positive effect, while perceived thwarting of basic psychological needs by friends have a negative effect on perceived well-being in friendships. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Rocchi et al. (2017), and Etkin et al. (2022). According to the self-determination theory (SDT), an agent in a social context that diminishes perceived autonomy or self-determination will decrease intrinsic motivation. Conversely, if social feedback supports autonomy and competence, intrinsic motivation will increase (Guay, 2022).

Other results indicated that goals in friendship relationships have a significant effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Gilbert et al. (2017) and Leung and Law (2019). Gilbert et al. (2017) showed a positive relationship between compassionate goals and cognitive empathy. Compassionate goals positively predicted empathy, while self-image goals negatively predicted empathy. Leung and Law (2019) concluded that the perception of the partner's intrinsic goals and the individual's own intrinsic goals are associated with higher relationship satisfaction, while the perception of the partner's extrinsic goals and the individual's own extrinsic goals are associated with lower relationship satisfaction. Crocker and Canevello (2008) believed compassionate goals are associated with positive relationship outcomes such as perceived support from roommates or friends and relationship satisfaction.

Furthermore, the research findings supported the significant effect of satisfied basic psychological needs on perceived well-being in friendship relationships. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Costa et al. (2015) and Kanat-Maymon et al. (2016). Gillison et al. (2019), in a systematic review of research based on the self-determination theory from 1970 to 2017, confirmed the impact of satisfaction of basic psychological needs and increasing intrinsic motivation on various health outcomes. Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT; Ryan, 1995) explains how the satisfaction (or frustration) of basic psychological needs influences well-being and optimal performance.

The results of friendship self-regulation showed that this construct has a positive effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships. Among the critical determinants, friendship self-regulation had the highest direct effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Soenens and Vansteenkiste (2005), Lee (2018), Okada (2007), and Okada (2012). Okada (2007) demonstrated that friendship self-regulation among high school students is related to satisfaction with friendship. Okada (2012) conducted another study on friendship self-regulation among university students and demonstrated that this construct can impact self-esteem by mediating aggression, anger, and hostility.

Results showed that supporting the basic psychological needs of friends has most negligible direct effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships, and this effect is positive. Thwarting the basic psychological needs of friends also has a direct negative effect on perceived well-being in friendship relationships. These findings are consistent with the reciprocal nature of close relationships (Deci, & Ryan, 2014; Ryan, & Deci, 2017) and Rocchi et al. (2017) and Sheldon et al. (2021) studies. Van der Kaap-Deeder et al. (2017) emphasized the importance of friendship relationships supporting autonomy. According to their view, individuals who support autonomy value their friends' perspectives and validate them, which helps them consult with their friends appropriately and stimulate a sense of autonomy. Therefore, the need for autonomy in friendships is satisfied when individuals are free to express their emotions in interactions with friends.

According to the importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA), the critical determinants of perceived well-being in friendship relationships, in order of importance, are goals in friendship relationships, satisfied basic psychological needs, perceived support of basic psychological needs by friends, supporting the basic psychological needs of friends, and friendship self-regulation. In the framework of the self-determination theory (Deci, & Ryan, 1985; Ryan, & Deci, 2020), it seems that when individuals perceive their friendships as supportive of their basic psychological needs and have compassionate goals in their friendships, their well-being in friendship relationships increases. This explanation achieved through satisfying of basic psychological needs, increased self-regulation, and the support of the basic psychological needs of friends. In such conditions, the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied when they consider their friends as valuable beings with human dignity, not merely as tools to achieve other goals. Friends also provide opportunities for them to make free choices in interactions and pay attention to their development of a sense of competence through timely and precise feedback, as well as care and support without conditions. In this way, individuals attain intrinsic motivation to support their friends' basic psychological needs and create a conducive environment through their behaviors to meet the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their friends. This approach, alongside the satisfaction of their friends' needs, contributes to better satisfying their basic psychological needs. Such an atmosphere in friendships enables individuals to feel vitality and energy in their interactions with friends, experience greater satisfaction in the relationship, have greater intimacy and trust in their friends, and move forward with a committed and empathetic approach.

Limitations of the present study include using self reported measures since the report consists of the participants’ perceptions, which can altered by the emotional state in which they answered or because they may manipulate information. Additionally, the data may have influenced by data collection method. It is possible that the random sampling did not indeed occur. Although the researcher attempted to maximize the presence of diverse subgroups of the community by selecting student groups on social networks, individuals who are less active may not have had equal opportunities to participate in this study.

The findings indicate the determinant roles of goals in friendship relationships, friendship self-regulation, and basic psychological needs in perceived well-being in friendship relationships. It appears necessary for individuals to have sufficient awareness and skills regarding identifying their goals and needs in their relationships with friends, as well as self-regulation in relationships. Based on this, it recommended that counselors in university empowerment and counseling centers prioritize these aspects in their educational workshops and individual consultations for students experiencing difficulties in interpersonal relationships.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for research, authorship, and, or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were under the ethical standards of the institutional and, or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Also, this study regulated by the professional law of the psychologist in Iran and the guidelines of research with humans of the American Psychology Association. This study obtained ethical approval from the committee with code number IR.UM.REC.1399.098.

Informed Consent

In the electronic forms, explanations given to the participants about the objectives of the project, while assuring them about the confidentiality of the information, the voluntary participation in the research emphasized, and at the end of the application, the student received information about the free line to obtain professional advice about issues mental health.

Open Practices

The raw data, analysis code, and materials used in this study are not openly available but are available upon request to the corresponding author. The instruments was digitized on the Google Docs platform with prior authorization from the authors. The sample recruited through the publication advertisements and informative comments in different groups of social networks popular among university students.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning to the research, authorship, and, or publication of this article.

References

- Arnett, J.J.; Mitra, D. Are the features of emerging adulthood developmentally distinctive? A comparison of ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerging Adulthood 2020, 8, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahraei, Z.; Hosseini Almadani, S.A.; Baseri, A. The Modeling Family Resilience based on Marital Happiness, Basic Psychological Needs and Spirituality with the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Islamic Life Journal 2022, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L. Incorporating psychopathology into the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior (IPTS). Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2021, 51, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, J.A.; Dunsmore, J.C.; Fivush, R. Adjustment factors of attachment hope and motivation in emerging adult well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2021, 22, 3259–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J. The clinical utility of a brief measure of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness for the detection of suicidal military personnel. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2011, 67, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmignola, M.; Martinek, D.; Hagenauer, G. At first I was overwhelmed but then—I have to say—I did almost enjoy it’. Psychological needs satisfaction and vitality of student teachers during the first Covid-19 lockdown. Social Psychology of Education 2021, 24, 1607–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Ntoumanis, N.; Bartholomew, K.J. Predicting the brighter and darker sides of interpersonal relationships: Does psychological need thwarting matter? Motivation and emotion 2015, 39, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W. “Family comes first!” Relationships with family and friends in Italian emerging adults. Journal of Adolescence 2014, 37, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Canevello, A. Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: the role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of personality and social psychology 2008, 95, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Autonomy and need satisfaction in close relationships: Relationships motivation theory. Human motivation and interpersonal relationships: Theory research and applications 2014, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M. Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies 2010, 11, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatshahee, B.; Yaghubi, H.; Riazi, S.A.; Peyravi, H.; Hassan Abadi, H.R.; Sobhi Ghramaleki, N. Construction and Validation of “National Scale of Students Life Profile”: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Applied Psychological Research 2016, 7, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumen, S.; Smits, I.; Luyckx, K.; Duriez, B.; Vanhalst, J.; Verschueren, K.; Goossens, L. Identity and perceived peer relationship quality in emerging adulthood: The mediating role of attachment-related emotions. Journal of adolescence 2012, 35, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; (No. 7); WW Norton & company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, R.G.; Bowker, J.C.; Simms, L.J. Friend overprotection in emerging adulthood: Associations with autonomy support and psychosocial adjustment. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 2022, 183, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, G.J.; Simpson, J.A.; Thomas, G. The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2000, 26, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaine, G.S.; La Guardia, J.G. The unique contributions of motivations to maintain a relationship and motivations toward relational activities to relationship well-being. Motivation and Emotion 2009, 33, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Catarino, F.; Sousa, J.; Ceresatto, L.; Moore, R.; Basran, J. Measuring competitive self-focus perspective taking submissive compassion and compassion goals. Journal of Compassionate Health Care 2017, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, F.B.; Rouse, P.; Standage, M.; Sebire, S.J.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychology Review 2019, 13, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W.S. The role of parents in facilitating autonomous self-regulation for education. Theory and Research in Education 2009, 7, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F. Applying self-determination theory to education: regulations types psychological needs and autonomy supporting behaviors. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2022, 37, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, N.H.; Holding, A.C.; Verner-Filion, J.; Sheldon, K.M.; Koestner, R. The path from intrinsic aspirations to subjective well-being is mediated by changes in basic psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: A large prospective test. Motivation and Emotion 2019, 43, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.A.; Nooroozi, Z.; Foolad Chang, M. The study of factor structure reliability and validity of basic empathy scale: Persian form. Journal of Educational Psychology Studies 2017, 14, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E., Jr. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of adolescence 2006, 29, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Roth, G.; Assor, A.; Raizer, A. Controlled by love: The harmful relational consequences of perceived conditional positive regard. Journal of Personality 2016, 84, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and social psychology bulletin 1996, 22, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.T.; Wang, J.C.; Erikson, K.; Côté, J. Experience in competitive youth sport and needs satisfaction: The Singapore story. International Journal of Sport Psychology 2012, 43, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kopala-Sibley, D.C.; Zuroff, D.C.; Hermanto, N.; Joyal-Desmarais, K. The development of self-definition and relatedness in emerging adulthood and their role in the development of depressive symptoms. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2016, 40, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.G.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Deci, E.L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment need fulfillment and well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology 2000, 79, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, J.; Sturges, D.; Schlote, R. Flipping the Classroom: Effects on Course Experience Academic Motivation and Performance in an Undergraduate Exercise Science Research Methods Course. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 2018, 18, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The Role of Motivational Resources in Maintaining Psychological Well-Being after Failure Experiences. Unpublished Thesis, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A.N.M.; Law, W. Do extrinsic goals affect romantic relationships? The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Motivation and Emotion 2019, 43, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibáñez, I.; Fortes, D.; Díaz, A. Gender differences in psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2022, 17, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.L.; Arnett J., J. Emerging Adulthood and Higher Education. A New Student Development Paradigm; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, R. Motivational analysis of academic help-seeking: Self-determination in adolescents' freindship. Psychological Reports 2007, 100, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, R. Friendship motivation aggression and self-esteem in Japanese undergraduate students. Psychology 2012, 3, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Carrasco, J.L.; Salgueiro, M.; Sayans-Jiménez, P.; Blanc-Molina, A.; García-Leiva, J.M.; Calandre, E.P.; Rojas, A.J. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the 12-item Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Anales De Psicología/Annals of Psychology 2018, 34, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özabacı, N.; Eryılmaz, A. The sources of self-esteem: Initating and maintaining romantic intimacy at emerging adulthood in Turkey. Journal of Human Sciences 2015, 12, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F.L.; Koestner, R.; Lekes, N. On the directive function of episodic memories in people's lives: A look at romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2013, 104, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratelle, C.F.; Simard, K.; Guay, F. University students’ subjective well-being: The role of autonomy support from parents friends and the romantic partner. Journal of Happiness Studies 2013, 14, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Jiang, S. Acculturation stress satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs and mental health of Chinese migrant children: Perspective from basic psychological needs theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.Y.B.J.M. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. 2015. http://www.smartpls.

- Rocchi, M.; Pelletier, L.; Cheung, S.; Baxter, D.; Beaudry, S. Assessing need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviours: The Interpersonal Behaviours Questionnaire (IBQ). Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 104, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation social development and well-being. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M. Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality 1995, 63, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of personality and social psychology 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation Development and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions theory practices and future directions. Contemporary educational psychology 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On energy personality and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of wellbeing. Journal of personality 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Curren, R.R.; Deci, E.L. What humans need: Flourishing in Aristotelian philosophy and self-determination theory. In A. S. Waterman (Ed.) The best within us: Positive psychology perspectives on eudaimonia (pp. 57–75). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B. Building a science of motivated persons: Self-determination theory’s empirical approach to human experience and the regulation of behavior. Motivation Science 2021, 7, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhadi, M.; Navidian, A.; Fasihi Harandy, T.; Ansari Moghadam, A. Comparing quality of marital relationship of spouses of patients with and without a history of myocardial infarction. Journal of Health Promotion Management 2013, 2, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, N.M.; Millea, M.A.; Diehl, J.J. Perceived autonomy support in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism-Open Access 2013, 3, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Corcoran, M.; Titova, L. Supporting One’s Own Autonomy May Be More Important Than Feeling Supported by Others. Motivation Science 2021, 7, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, S.; Scharf, M.; Livne, Y.; Barr, T. Patterns of romantic involvement among emerging adults: Psychosocial correlates and precursors. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2013, 37, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, K.; Mälkki, K.; Sandström, N.; Lonka, K. Does Physical Environment Contribute to Basic Psychological Needs? A Self-Determination theory Perspective on Learning in the Chemistry Laboratory. Frontline Learning Research 2016, 4, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M. Antecedents and outcomes of self-determination in 3 life domains: The role of parents' and teachers' autonomy support. Journal of youth and adolescence 2005, 34, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F.; Kareshki, H.; Amin Yazdi, S.A. Psychometric Properties of the Friendship Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-F) at the Emerging Adulthood. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology 2021, 4, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F.; Kareshki, H.; Torkamani, M. Psychometric Properties of State Level Subjective Vitality Scale based on classical test theory and Item-response theory. Rooyesh 2019, 8, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F.; Saeidi Rezvani, T.; Samadiye, H.; Kareshki, H. Psychometric Properties of the Basic Need Satisfaction in Relationships with Friends Scale. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, L.; Cree, V.E.; Christie, H. From further to higher education: transition as an on-going process. Higher Education 2017, 73, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Boone, L.; Brenning, K. Antecedents of provided autonomy support and psychological control within close friendships: The role of evaluative concerns perfectionism and basic psychological needs. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 108, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Song, Y. Will materialism lead to happiness? A longitudinal analysis of the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 105, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).