Submitted:

30 September 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

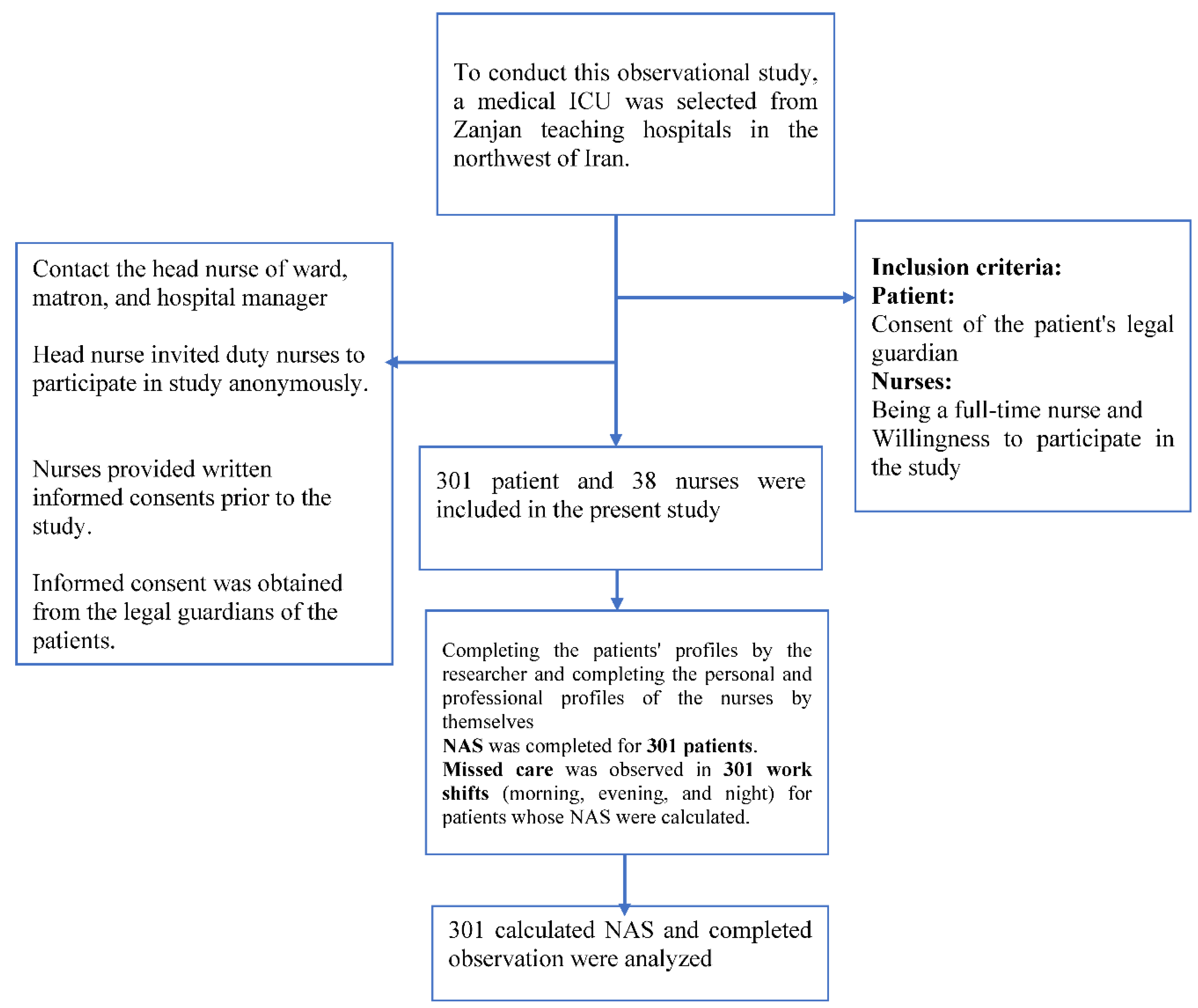

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

6. Strength and limitation

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereira Lima Silva R, Gonçalves Menegueti M, Dias Castilho Siqueira L, de Araújo TR, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Mantovani Silva Andrade L, Laus AM. Omission of nursing care, professional practice environment and workload in intensive care units. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(8):1986-96. [CrossRef]

- Lebet RM, Hasbani NR, Sisko MT, Agus MSD, Nadkarni VM, Wypij D, Curley MAQ. Nurses’ Perceptions of Workload Burden in Pediatric Critical Care. American Journal of Critical Care. 2021;30(1):27-35. [CrossRef]

- Chang LY, Yu HH, Chao YC. The Relationship Between Nursing Workload, Quality of Care, and Nursing Payment in Intensive Care Units. Journal of Nursing Research. 2019;27(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi MG. Nursing workload: a concept analysis. Journal of Nursing Management. 2016;24(4):449-57. [CrossRef]

- Tubbs-Cooley HL, Mara CA, Carle AC, Mark BA, Pickler RH. Association of Nurse Workload With Missed Nursing Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019;173(1):44-51.

- Carvalho DPd, Rocha LP, Pinho ECd, Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, Barlem ELD, Goulart LS. Workloads and burnout of nursing workers. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2019;72(6):1435-41. [CrossRef]

- Pastores SM, Kvetan V, Coopersmith CM, Farmer JC, Sessler C, Christman JW, D’Agostino R, Diaz-Gomez J, Gregg SR, Khan RA, Kapu AN, Masur H, Mehta Gargi, Moore J, Oropello JM, Price K. Workforce, Workload, and Burnout Among Intensivists and Advanced Practice Providers: A Narrative Review. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(4):550-557. [CrossRef]

- Orique SB, Patty CM, Woods E. Missed Nursing Care and Unit-Level Nurse Workload in the Acute and Post-Acute Settings. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2016;31(1):84-9. [CrossRef]

- Chaboyer W, Harbeck E, Lee B-O, Grealish L. Missed nursing care: An overview of reviews. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021;37(2):82-91. [CrossRef]

- Jones TL, Hamilton P, Murry N. Unfinished nursing care, missed care, and implicitly rationed care: State of the science review. International journal of nursing studies. 2015;52(6):1121-37. [CrossRef]

- Juvé-Udina M-E, González-Samartino M, López-Jiménez MM, Planas-Canals M, Rodríguez-Fernández H, Batuecas Duelt IJ, Tapia-Pérez M, Pons Prats M, Jiménez-Martínez E, Barberà Llorca MÀ, Asensio-Flores S, Berbis-Morelló C, Zuriguel-Pérez E, Delgado-Hito P, Rey Luque Ó, Zabalegui A, Fabrellas N, Adamuz J. Acuity, nurse staffing and workforce, missed care and patient outcomes: A cluster-unit-level descriptive comparison. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(8):2216-29. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Wojcik B, Gaworska-Krzemińska A, Owczarek AJ, Kilańska D. In-hospital mortality as the side effect of missed care. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(8):2240-6. [CrossRef]

- Janatolmakan M, Khatony A. Explaining the consequences of missed nursing care from the perspective of nurses: a qualitative descriptive study in Iran. BMC nursing. 2022;21(1):1-7.

- Bae S-H, Kim J, Lee I, Oh SJ, Shin S. Video Recording of Nursing Care Activities in Gerontological Nursing to Compare General Units and Comprehensive Nursing Care Units. Journal of Korean Gerontological Nursing. 2019;21(3):165-72. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh M, Heidari Gorji MA, Khalilian AR, Esmaeili R. Assessment of nursing workload and related factors in intensive care units using the nursing activities score. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2015;24(122):147-57.

- Nieri A-S, Manousaki K, Kalafati M, Padilha KG, Stafseth SK, Katsoulas T, Matziou V, Giannakopoulou M. Validation of the nursing workload scoring systems “Nursing Activities Score” (NAS), and “Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System for Critically Ill Children” (TISS-C) in a Greek Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018;48:3-9. [CrossRef]

- Luiking ML, van Linge R, Bras L, Grypdonck M, Aarts L. Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the American Nursing Activity Scale in an intensive care unit. Journal of advanced nursing. 2012;68(12):2750-5. [CrossRef]

- Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the cross-cultural adaptation of health status measures. New York: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2002;12:1-29.

- Kim KS, Kwon S-H, Kim J-A, Cho S. Nurses’ perceptions of medication errors and their contributing factors in South Korea. Journal of Nursing Management. 2011;19(3):346-53. [CrossRef]

- Taheri HabibAbadi E, Noorian M, Rassouli M, Kavousi A. Nurses' Perspectives on Factors Related to Medication Errors in Neonatal and Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Iran Journal of Nursing (2008-5923). 2013;25(80).

- Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, Morrow E, Griffiths P. ‘Care left undone’ during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2014;23(2):116. [CrossRef]

- Kim K-J, Yoo MS, Seo EJ. Exploring the Influence of Nursing Work Environment and Patient Safety Culture on Missed Nursing Care in Korea. Asian Nursing Research. 2018;12(2):121-6. [CrossRef]

- Joolaee S, Shali M, Hooshmand A, Rahimi S, Haghani H. The relationship between medication errors and nurses’ work environment. Medical-Surgical Nursing Journal. 2016;4(4):e68079.

- Kalisch BJ, Williams RA. Development and Psychometric Testing of a Tool to Measure Missed Nursing Care. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2009;39(5):211-219. [CrossRef]

- Momennasab M, Karimi F, Dehghanrad F, Zarshenas L. Evaluation of Nursing Workload and Efficiency of Staff Allocation in a Trauma Intensive Care Unit. Trauma Monthly. 2018;23(1):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Bruyneel A, Tack J, Droguet M, Maes J, Wittebole X, Miranda DR, Pierdomenico LD, Measuring the nursing workload in intensive care with the Nursing Activities Score (NAS): A prospective study in 16 hospitals in Belgium. Journal of Critical Care. 2019;54:205-11. [CrossRef]

- Camuci MB, Martins JT, Cardeli AAM, Robazzi MLdCC. Nursing Activities Score: nursing workload in a burns Intensive Care Unit. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem. 2014;22(2):325-31. [CrossRef]

- Padilha KG SS, Solms D, Hoogendoom M, Monge FJC, Gomaa OH, Giakoumidakis K, Giannakopoulou M, Gallani MC, Cudak E, Nogueira LS, Santoro C, Sousa RC, Barbosa RL, Miranda DR. Nursing Activities Score: an updated guideline for its application in the Intensive Care Unit. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2015;49(spe):131-7. [CrossRef]

- Chegini Z, Jafari-Koshki T, Kheiri M, Behforoz A, Aliyari S, Mitra U, Islam SMS. Missed nursing care and related factors in Iranian hospitals: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(8):2205-15. [CrossRef]

- Haftu M, Girmay A, Gebremeskel M, Aregawi G, Gebregziabher D, Robles C. Commonly missed nursing cares in the obstetrics and gynecologic wards of Tigray general hospitals; Northern Ethiopia. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0225814. [CrossRef]

- Ball JE, Griffiths P, Rafferty AM, Lindqvist R, Murrells T, Tishelman C. A cross-sectional study of ‘care left undone’ on nursing shifts in hospitals. Journal of advanced nursing. 2016;72(9):2086-97. [CrossRef]

- Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Younger JB, Mark BA. A descriptive study of nurse-reported missed care in neonatal intensive care units. Journal of advanced nursing. 2015;71(4):813-24. [CrossRef]

- Zang K, Chen B, Wang M, Chen D, Hui L, Guo S, Ji T, Shang F. The effect of early mobilization in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Nursing in Critical Care. 2020;25(6):360-7. [CrossRef]

- Biswas A, Bhattacharya SD, Singh AK, Saha M. Addressing Hand Hygiene Compliance in a Low-Resource Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: a Quality Improvement Project. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2019;8(5):408-13. [CrossRef]

- Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Mark BA, Carle AC. A research protocol for testing relationships between nurse workload missed nursing care and neonatal outcomes: the neonatal nursing care quality study. Journal of advanced nursing. 2015;71(3):632-41. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths P, Recio-Saucedo A, Dall'Ora C, Briggs J, Maruotti A, Meredith P, Smith GB, Ball J. The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: A systematic review. Journal of advanced nursing. 2018;74(7):1474-87. [CrossRef]

- Ogboenyiya AA, Tubbs-Cooley HL, Miller E, Johnson K, Bakas T. Missed Nursing Care in Pediatric and Neonatal Care Settings: An Integrative Review. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2020;45(5). [CrossRef]

- Tajabadi A, Ahmadi F, Sadooghi Asl A, Vaismoradi M. Unsafe nursing documentation: A qualitative content analysis. Nursing Ethics. 2019;27(5):1213-24. [CrossRef]

- De Marinis MG, Piredda M, Pascarella MC, Vincenzi B, Spiga F, Tartaglini D, Alvaro R, Matarese M. ‘If it is not recorded, it has not been done!’? consistency between nursing records and observed nursing care in an Italian hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(11-12):1544-52. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei S, Noorihekmat S, Oroomiei N, Vali L. Administrative challenges of clinical governance in military and university hospitals of Kerman/Iran. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2019;34(2):e1293-e301. [CrossRef]

- Hessels AJ, Paliwal M, Weaver SH, Siddiqui D, Wurmser TA. Impact of Patient Safety Culture on Missed Nursing Care and Adverse Patient Events. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2019;34(4):287-94. [CrossRef]

- Reis CT, Paiva SG, Sousa P. The patient safety culture: a systematic review by characteristics of Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture dimensions. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2018;30(9):660-77. [CrossRef]

- Phelan A, McCarthy S, Adams E. Examining missed care in community nursing: A cross-section survey design. Journal of advanced nursing. 2018;74(3):626-36. [CrossRef]

- Lake ET, French R, O'Rourke K, Sanders J, Srinivas SK. Linking the work environment to missed nursing care in labour and delivery. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(8):1901-8. [CrossRef]

- Smith JG, Morin KH, Wallace LE, Lake ET. Association of the Nurse Work Environment, Collective Efficacy, and Missed Care. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2017;40(6):779-98. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Hoben M, Norton P, Estabrooks CA. Association of Work Environment With Missed and Rushed Care Tasks Among Care Aides in Nursing Homes. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):e1920092-e. [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) | Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Employment status | ||

| Female | 31 (81.58) | Casual employees | 24 (68.16) |

| Male | 7 (18.42) | Fixed employment contracts | 5 (13.16) |

| Age (years) | Permanent full-time employment | 9 (23.98) | |

| 22-30 | 25 (65.78) | Work experiences (years) | |

| 31-40 | 13 (34.21) | 6 month-2 years | 10 (26.32) |

| Marital status | 3 years-5 years | 19 (50) | |

| Single | 8 (21.05) | 6 years- 10 years | 7 (18.42) |

| Married | 30 (78.95) | 11 years-15 years | 2 (5.26) |

| Educational level | Number of working hours/months | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 35 (92.11) | >200 hours | 2 (5.3) |

| Master’s degree | 3 (7.89) | 208-240 hours | 20 (52.6) |

| Nurse-to-patient ratio | < 240 hours | 16 (42.1) | |

| 1:1 | 4 (10.5) | working hours / months | |

| 1:2 | 27 (71.1) | 200 hours/month | 2 (5.3) |

| 1:3 | 7 (18.4) | 200-240 hours/month | 20 (52.6) |

| >240 hours/month | 16 (42.1) |

| Missed cares | Not applicable N (%) |

Not done N (%) |

Done incompletely N (%) |

Don completely N (%) |

| Assessment | ||||

| Patient Identification with patient bracelet during shift delivery | 13 (4.3) | 288 (95.7) | ||

| Attention to ventilator settings at the beginning of the shift | 140 (46.5) | 149 (49.5) | 12 (4.0) | |

| Assessment and recording the patient’s mental state (delirium, depression and anxiety) | 120 (39.9) | 107 (35.5) | 64 (21.3) | 10 (3.3) |

| Control vital signs and record them in time according to the order | 25 (8.3) | 8 (2.7) | 167 (55.5) | 101 (33.6) |

| Report abnormal vital signs immediately after being notified | 282 (93.7) | 9 (3.0) | 6 (2.0) | 4 (1.3) |

| Assessment and evaluation and re-recording if the patient’s condition changes | 292 (97.0) | 7 (2.3) | 1 (.3) | 1 (.3) |

| Control and record blood sugar according to the order | 159 (52.8) | 92 (30.6) | 12 (4.0) | 38 (12.6) |

| Taking appropriate treatment in case of abnormal blood sugar within 15 minutes | 300 (99.7) | 1 (.3) | ||

| Checking the correct location of the endotracheal tube and measuring endotracheal tube cuff pressure at least once per shift | 208 (69.1) | 78 (25.9) | 4 (1.3) | 11 (3.7) |

| Skin and vascular assessment of the upper and lower limbs at the place of restriction | 142 (47.2) | 149 (49.5) | 3 (1.0) | 7 (2.3) |

| Assessment and recording of SPO 2 of the patient | 67 (22.3) | 104 (34.6) | 21 (7.0) | 109 (36.2) |

| Treatment for abnormal SPO2 within 5 minutes | 236 (78.4) | 7 (2.3) | 56 (18.6) | 2 (.7) |

| Assessment the need for suction and performing it on time | 108 (35.9) | 123 (40.9) | 59 (19.6) | 11 (3.7) |

| Recording of endotracheal tube secretions volume and its characteristics | 217 (72.1) | 1 (.3) | 1 (.3) | 82 (27.2) |

| Checking and recording the content characteristics of the bag connected to the nasogastric tube | 291 (96.7) | 5 (1.7) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Reporting the abnormal content of nasogastric tube secretions | 293 (97.3) | 6 (2.0) | 2 (.7) | |

| Measuring the volume and color of urine and recording it | 1 (.3) | 1 (.3) | 2 (19) | 280 (93) |

| Reporting the abnormal the volume and color of urine | 281 (93.4) | 16 (5.3) | 1 (.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Assessment and recording the volume and color of chest tube discharges | 292 (97.0) | 3 (1.0) | 6 (2.0) | |

| Reporting abnormal the volume and color of chest tube discharges | 296b (98.3) | 1 (.3) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Assessment and recording the status of any kind of drain or wound | 290 (96.3) | 1 (.3) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Reporting the abnormal discharge of any type of drain or wound | 294 (97.7) | 5 (1.7) | 1 (.3) | 1 (.3) |

| Mobility and motion | ||||

| Change position every 2 hours | 300 (99.7) | 1 (.3) | ||

| Moving and walking the patient according to the order | 296 (98.3) | 5 (1.7) | ||

| Applying deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prevention: intermittent bandaging or Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) | 137 (45.5) | 162 (53.8) | 2 (.7) | |

| Using proper protection and restraint (bed side rail and bed harness) | 31 (10.3) | 21 (7.0) | 140 (46.5) | 109 (36.2) |

| Response to patient’s needs and devices alarmwithin 5 min | ||||

| Response to the rational request of the patient (defecation, thirst, hunger, movement, etc.) within 5 minutes of the request | 266 (88.4) | 1 (.3) | 29 (9.6) | 5 (1.7) |

| Responding to device alarms within 1 to 5 minutes of its start | 23 (7.6) | 43 (14.3) | 144 (47.8) | 91 (30.2) |

| Patient education | ||||

| Explaining and education to the conscious patient before performing the procedures |

237 (78.7) | 7 (2.3) | 7 (2.3) | 50 (16.6) |

| Explaining and education to the conscious patient after the procedures | 244 (81.1) | 7 (2.3) | 5 (1.7) | 45 (15.0) |

| Hand hygiene | ||||

| Hand hygiene before touching a patient | 100 (33.2) | 201 (66.8) | ||

| Hand hygiene before performing care procedures | 103 (34.2) | 198 (65.8) | ||

| Hand hygiene after performing care procedures | 6 (2.0) | 291 (96.7) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Hand hygiene after body fluid exposures risk | 2 (.7) | 5 (1.7) | 294 (97.7) | |

| Hand hygiene after touching a patient | 1 (.3) | 12 (4.0) | 288 (95.7) | |

| Infection control | ||||

| Eye care based according to hospital policy | 253 (84.1) | 35 (11.6) | 11 (3.7) | 2 (.7) |

| Skin care on ward according to hospital policy | 228 (75.7) | 42 (14.0) | 14 (4.7) | 17 (5.6) |

| Mouthwash based on the needs of the patient in each shift | 241 (80.1) | 34 (11.3) | 13 (4.3) | 13 (4.3) |

| Perineal Care: Washing the perineum based on the ward’s routine | 253 (84.1) | 18 (6.0) | 13 (4.3) | 17 (5.6) |

| Caring for any type of wound on the body (rinsing the wound if necessary and dressing) | 277 (92.0) | 8 (2.7) | 9 (3.0) | 7 (2.3) |

| Central venous catheter dressing | 281 (93.4) | 5 (1.7) | 15 (5.0) | |

| Replacement of venous line within half an hour of phlebitis | 294 (97.7) | 1 (.3) | 2 (.7) | 4 (1.3) |

| Prevention of contact of drains, bags and connections of the patient with the ground | 22 (7.3) | 1 (.3) | 1 (.3) | 277 (92.0) |

| Change the direction of the endotracheal tube to prevent ischemia at least once per shift | 196 (65.1) | 104 (34.6) | 1 (.3) | |

| change of disposable devices according to hospital policy (micro set, serum, serum set, central venous pressure monitor equipment, infusion syringe, extension tube, Foley catheter, nasogastric tube, feeding set, gavage syringe, closed suction, etc.) | 200 (66.4) | 6 (2.0) | 95 (31.6) | |

| Oxygen Therapy | ||||

| Resetting the new ventilator items according to the order within 10 minutes | 301 (100) | |||

| Appropriately providing oxygenation according to the order | 48 (15.6) | 10 (3.3) | 10 (3.3) | 233 (77.4) |

| Implementation of urgency order | ||||

| Execution of STAT medication orders within 15 minutes after the order | 170 (56.5) | 5 (1.7) | 126 (41.9) | |

| Sending emergency samples within 15 minutes after the order | 170 (56.5) | 5 (1.7) | 126 (41.9) | |

| The nutritional care | ||||

| Feeding the patient within 15 minutes after food distribution | 137 (45.5) | 3 (1.0) | 68 (22.6) | 93 (30.9) |

| Measuring gastric residual volume | 193 (64.1) | 85 (28.2) | 6 (2.0) | 17 (5.6) |

| Adjusting the feed pump | It was not evaluated due to the absence of nutritional bag in the ward during the study. | |||

| Filling the bag connected to the feeding pump within 15 minutes after its completion | ||||

| Observing the semi-sitting position during feeding | 134 (44.5) | 2 (.7) | 33 (11.0) | 132 (43.9) |

| Not applicable N (%) |

Very high N (%) |

High N (%) |

Moderate N (%) |

Low N (%) |

Mean (95% CI) (1-10 score) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | - | - | 5 (1.7) | 209 (69.4) | 87 (28.9) | 70.32 (69.05, 71.54) |

| Mobility and motion | 14 (4.7) | 5 (1.7) | 91 (30.2) | 163 (54.2) | 28 (9.3) | 58.88 (56.44, 61.26) |

| Response to patient’s needs and call lightwithin 5 min | 1 (.3) | - | 45 (15) | 159 (52.8) | 96 (31.9) | 71.93 (69.43, 74.47) |

| Patient education | 234 (77.7) | - | 8 (2.7) | 9 (3.0) | 50 (16.6) | 19.49 (34.46, 41.27) |

| Hand hygiene | - | - | 6 (2.0) | 293 (97.3) | 2 (.7) | 68.37 (67.55, 69.15) |

| Infection control | - | - | 20 (6.6) | 105 (34.9) | 176 (58.5) | 80.90 (78.75, 82.92) |

| Oxygen Therapy | 48 (15.9) | - | 10 (3.3) | 10 (3.3) | 233 (77.4) | 80.73 (76.52,84.93) |

| Implementation of urgency order | 178 (59.1) | - | - | 5 (1.7) | 118 (39.2) | 40. 31 (34.77,45.95) |

| The nutritional care | 139 (46.2) | - | 1 (.3) | 64 (21.3) | 97 (32.2) | 42.84 (38.13, 47.80) |

| Total of missed care score | - | - | 114 (37.9) | 184 (61.1) | 3 (1) | 59.31 (58.32, 60.43) |

| Variable | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very high | High | Moderate | Low | Not applicable | df | F | p | |

| Assessment | 67.26 (61.26, 74.37) | 77.70 (75.80,79.42) | 73.49 (70.99,76.63) | 2 | 3.90 | .021 | ||

| Mobility and motion | 75.64 (70.44,80.71) | 73.56 (69.16, 77.96) | 74.46 (71.62, 77.55) | 77.47 (75.23,79.48) | 76.43 (71.77, 80.98) | 4 | .73 | .573 |

| Response to patient’s needs and call lightwithin 5 min | 78.05 (74.34, 82.13) | 74.61 (72.49, 76.86) | 78.31 (75.55,81.03) | 75.40 (75.4, 75.4) | 3 | 1.67 | .174 | |

| Patient education | 82.66 (73.25, 92.73) | 78.33 (65.21,90.23) | 73.62 (70.06,76.96) | 76.59 (74.77, 78.37) | 3 | 1.26 | .289 | |

| Hand hygiene | 82.40 (69.32, 95.73) | 76.02 (74.44,77.48) | 100 (100, 100) | 2 | 3.70 | .026 | ||

| Infection control | 78.55 (71.18, 86.82) | 78.74 (75.98,81.48) | 74.60 (72.80, 76.41) | 2 | 3.19 | .043 | ||

| Oxygen Therapy | 74.07 (64.02, 83.54) | 80.24 (70.98, 90.80) | 76.31 (74.66, 78.14) | 75.96 (72.15,79.67) | 3 | .36 | .79 | |

| Implementation of urgency order | 83.10 (73.46,91.68) | 77.46 (74.72, 80.00) | 75.36 (73.34, 77.23) | 2 | 1.40 | .249 | ||

| The nutritional care | 106.70 (106.70, 106.70) | 75.11 (71.59, 78.39) | 75.45 (72.40, 78.40) | 77.25 (75.10, 79.43) | 3 | 2.08 | .104 | |

| Total of missed care score | 76.24 (73.04, 79.49) | 76.31 (74.52,78.25) | 76.52 (69.05, 83.61) | 2 | .002 | .998 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).