1. Keap1/Nrf2, a (mostly) metazoan family affair crucial to protect against stress

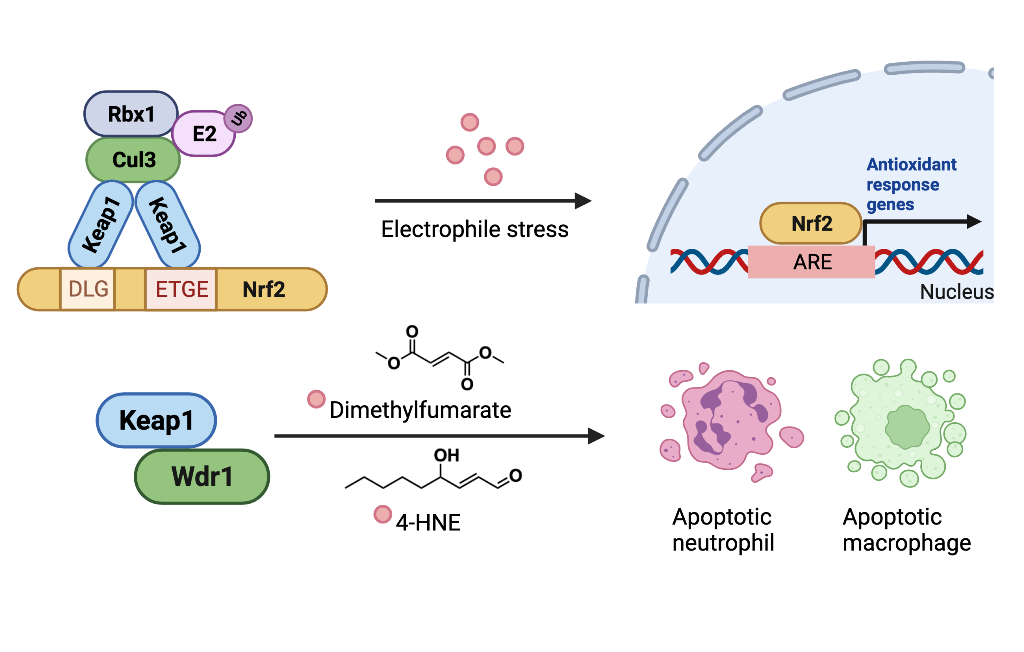

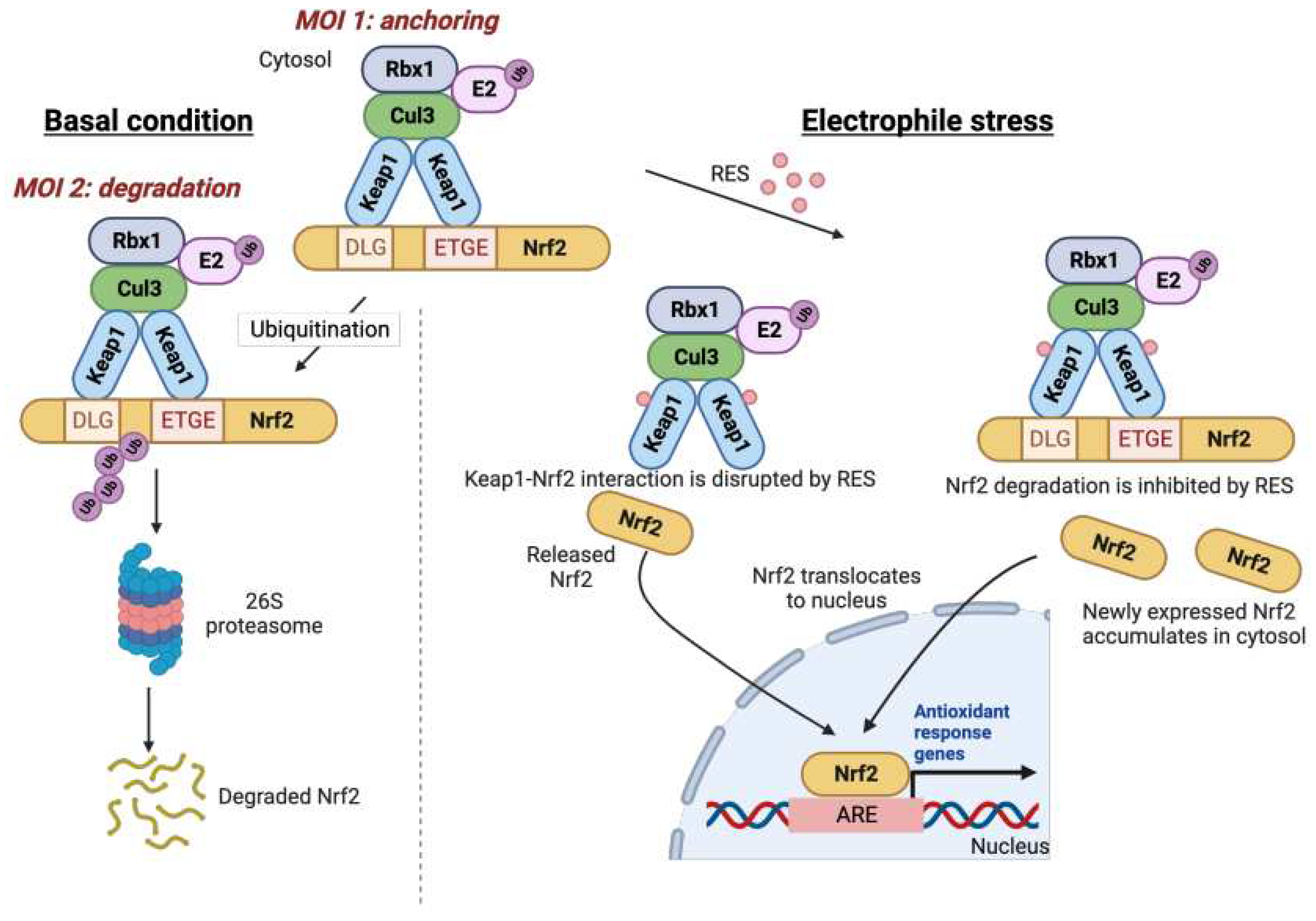

Of the now plentiful examples of signaling pathways susceptible to target-specific RES regulation, including immune response, DNA damage, apoptosis, and transcription, one of the oldest known, the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway remains the best studied and most well-understood. In its simplest form, Nrf2 is a transcription factor that upregulates cytoprotective genes essential for safe-guarding against numerous reactive molecules. Keap1 is an inhibitor of Nrf2. In resting cells, Keap1 and Nrf2 form a cytosolic complex. This complex physically prevents Nrf2 from entering the nucleus [mode of inhibition (MOI) 1]. Moreover, when complexed to Nrf2, Keap1 can also promote Nrf2 degradation (MOI 2). Nonetheless, under conditions where cellular stresses are elevated with associated increased RES production, Keap1 can be modified ultimately augmenting Nrf2 expression, increasing Nrf2 transcriptional activity. The step-wise molecular events of Nrf2 signaling upregulation induced upon reactive small-molecule stress however remains unsettled. Several authors have proposed that Nrf2 is released from Keap1, boosting Nrf2 signaling, although a recent in vitro study indicates RES modification does not cause Nrf2 dissociation from Keap1.

[1] Conversely, inhibition of Nrf2 degradation, and new synthesis of Nrf2 have also been proposed.

[2] (

Figure 1) Regardless of the intricacies, this pathway is almost entirely conserved between numerous non-vertebrate marine species, such as octopuses, as well as frog, fish, and higher vertebrates. Indeed, it is also apparent in relatively simple metazoans such as Drosophila, although

C. elegans and hydra appear to lack a true analog of Keap1, and rely on other Nrf2 regulation methods.

[3] Evidence for the necessity of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway can be found from the fact that Keap1 homozygous knockout (KO) mice show severe hyperkeratosis and die in infancy; Nrf2/Keap1 double KO mice are viable.

[4] Nrf2 KO mice alone are viable, but show severe issues in response to reactive small-molecule stresses.

2. Duplication aids investigation of function

In our recent work,

[5] we investigated the Keap1/Nrf2 system in zebrafish

D. rerio. Zebrafish is a particularly interesting model system in which to study protein function due to a genome duplication that occurred in teleost fish, meaning that zebrafish contain two copies of many of their genes. This is indeed the case for Keap1 and Nrf2, which express isoforms labeled a and b. In the case of Keap1, on which we will focus here, Keap1b is often considered the paralog closer to human Keap1 than Keap1a, although there is overall good homology between both paralogs and the human protein (~50% identity for Keap1a and ~80% for Keap1b) (

Figure 2a,b). In numerous instances, different paralogs have adopted tissue-specific functions, likely tailored to specific requirements of the particular tissues in which they are expressed.

[6,7] This is indeed often assumed in zebrafish biology. However, different zebrafish paralogs can also be expressed in the same tissues, although expression patterns over development may be different.

[8] In our case, we found that both Keap1 paralogs are expressed in the head and the tail of the fish, albeit at different levels. Thus, both paralogs are likely present at least some of the time in the same tissues. Intriguingly, we found that knockdown of Keap1a and Keap1b caused disparate outcomes in terms of Nrf2 signaling in zebrafish embryos: when embryos were exposed to electrophilic stress, Keap1a depletion led to upregulation of Nrf2 signaling in both the head and the tail of zebrafish. The opposite was observed for Keap1b. These data are consistent with findings reported by others.

[9] These data indicating a dampening effect of RES-induced Nrf2 signaling by Keap1a and a stimulatory action by Keap1b under electrophilic stress, implied that the two paralogs of Keap1 in zebrafish have very different roles. We initially hypothesized that Keap1a and Keap1b sensed electrophiles differently, namely that Keap1a could not sense electrophiles whereas Keap1b could. However, further experiments leveraging precision electrophile-sensitivity interrogation tools revealed that this was not the case for these paralogs against several known Nrf2-inducing native RES. These outcomes indicated that another effect was at play.

Additional experiments examining the two paralogs separately in cultured cells showed that despite being sensitive to electrophiles, electrophile modification of Keap1a does not allow RES-induced upregulation of Nrf2 signaling. However, Keap1b is permissive for this process. Such combination of permissivity and non-permissivity of RES-driven Nrf2 signaling could explain a large amount of our observations from fish, but not all. This is because if this model were true, knockdown of Keap1a should

not increase RES-induced Nrf2 signaling. We thus postulated that Keap1a could function in a dominant-negative manner for RES-induced Nrf2 signaling, through the formation of Keap1a/b heterodimers. Indeed, when Keap1a was co-expressed with Keap1b in cultured cells, suppression of RES-promoted Nrf2 signaling was observed relative to Keap1b expression alone. Thus, Keap1a can prevent RES-driven Nrf2 signaling, even when the permissive paralog, Keap1b, is present. We next considered the mechanism by which such a process could function. In our hands, Nrf2 co-precipitated with both Keap1a and Keap1b paralogs, as well as a 1:1 mixture of the twain. However, only in the case of Keap1b, was there found to be a release of Nrf2 from Keap1(a/b) post electrophilic stress. This model is consistent with RES-induced Nrf2 signaling occurring through Nrf2 release that is possible in Keap1b, but not in Keap1a. Since Keap1b responds similarly to electrophiles as human Keap1, and this outcome is concordant with phylogenetic analyses, we searched for a residue that differs between Keap1b and Keap1a that may be responsible for the latter’s non-canonical behavior. We narrowed down the search to cysteine residues in Keap1b that are mutated to hydrophobic residues in Keap1a. Through this method, we identified C273I as a potential candidate residue. Human Keap1(C273I) indeed showed similar dominant-negative properties for electrophile-triggered Nrf2 signaling (

Figure 2).

3. Cul3 comes into the fold

Intriguingly, recently it has been reported by Yumimoto et al. in a very thought-provoking paper, that Keap1a (and orthologs) interacts better than Keap1b (and orthologs) with Cul3, the E3 ligase responsible for Keap1-mediated Nrf2 degradation.

[10] This has also been proposed as an explanation for why Keap1a is less responsive to electrophile and oxidant stressors. Indeed, we observed less Nrf2 co-immunoprecipitating with Keap1a than Keap1b, which could readily be explained by such a mechanism. A simple amalgamation of both models leads to the hypothesis that Keap1a is so efficient at degrading bound Nrf2 that it cannot release enough Nrf2 to allow a boost in Nrf2 signaling upon electrophile exposure; Keap1b does build up Nrf2 so it can release Nrf2 upon electrophile labeling. However, in the absence of electrophilic stress, we showed that in a system where Keap1a and Keap1b were equally expressed, Nrf2 co-precipitating with the Keap1 ensemble was similar, albeit lower than Nrf2 co-precipitating with Keap1b alone. Even in that ensemble system, there was no release of Nrf2 upon whole-cell electrophile stress and Nrf2 signaling was compromised. These data indicate that Nrf2 release from electrophile-modified Keap1, is crucial for Nrf2 signaling, at least in the expressing system used in this study. In the case of Yumimoto et al.’s paper, even though an overexpression system was used, similar comparisons were unfortunately not investigated. However, interesting data for heterozygotic Keap1a-like/WT mice are reported, in addition to WT/WT and Keap1a-like/Keap1a-like mice. Although statistical comparisons between Keap1a-like/WT heterozygote and the two homozygotes were not explicitly made, in some instances, including most assays for response to oxidative stress, only modest differences between the heterozygote and the WT homozygote were observed. Such a situation might be explained by the fact that sufficient reduction of Nrf2 occupancy on Keap1 to suppress Nrf2 signaling upon stress can only be obtained in the Keap1a-like/Keap1a-like mutant homozygote. It should also be noted that Keap1a contains the C273I mutation that is known to affect Keap1 activity, and hence it is unlikely that solely increasing affinity to Cul3 would be responsible for all the differences between Keap1a and Keap1b. Nonetheless, Keap1a’s increased affinity to Cul3 could explain, for instance, why human KEAP1(C273I) elicits reduced Nrf2-activity suppression, whereas Keap1a does not in the absence of electrophile treatment (

Figure 2c).

Obviously, future studies of Keap1-mutants should involve careful evaluations of phenotypes associated with heterozygotic states (or co-expression systems) to enable a deeper understanding of specific proteins’ behaviors. Such insights are particularly important to assess the release versus degradation inhibition model of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling. Nonetheless, all data pointing to various subtleties and likely overlapping signaling mechanisms, much of the emerging data, including ours and that of Yumimoto et al., are at least in our opinion, more consistent with a model where RES-induced Keap1/Nrf2 signaling event is dominated by Nrf2 release. Indeed, if Nrf2 signaling upon electrophile stress were solely caused by inhibition of Nrf2 degradation, Keap1a should be more able to upregulate Nrf2 signaling than Keap1b that is less proficient at Nrf2 degradation. In fact, Keap1a is dominant negative for Nrf2 signaling relative to Keap1b.

4. Keap1 plays away from home

That being said, as underscored by studies from several independent laboratories, Keap1 does not only interact with Nrf2. Indeed, a large number of proteins (often those containing an ETGE motif,

Table 1), associated with numerous different cellular functions, are Keap1 interactors. Several of these Keap1 interactions are increased upon electrophilic or reactive oxygen stress.

[11] This has led various propositions that several proteins compete with Nrf2 for a similar Keap1 binding site,

[12] although the response to stressors indicates that regulation of these interactions must be different from the canonical Nrf2/Keap1 interaction. How this could factor into endogenous electrophile signaling systems in a specific biological context is poorly understood. Of course such concerns are particularly relevant to tissue-/cell-type-specific signaling differences. To some extent such concerns are mitigated in many of the systems used to study Keap1 and Nrf2, as they use overexpression, winnowing the contribution of these competitors. However, such contributions may be severely misregulated in cancer cells, that are the most common system studied. Thus, Keap1-Nrf2-signaling / regulation is best assayed in close-to-physiological systems such as zebrafish and mice. This point further underlines the need to incorporate a broad range of model systems for better understanding of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling modalities.

5. Nrf2 – the black sheep of the family?

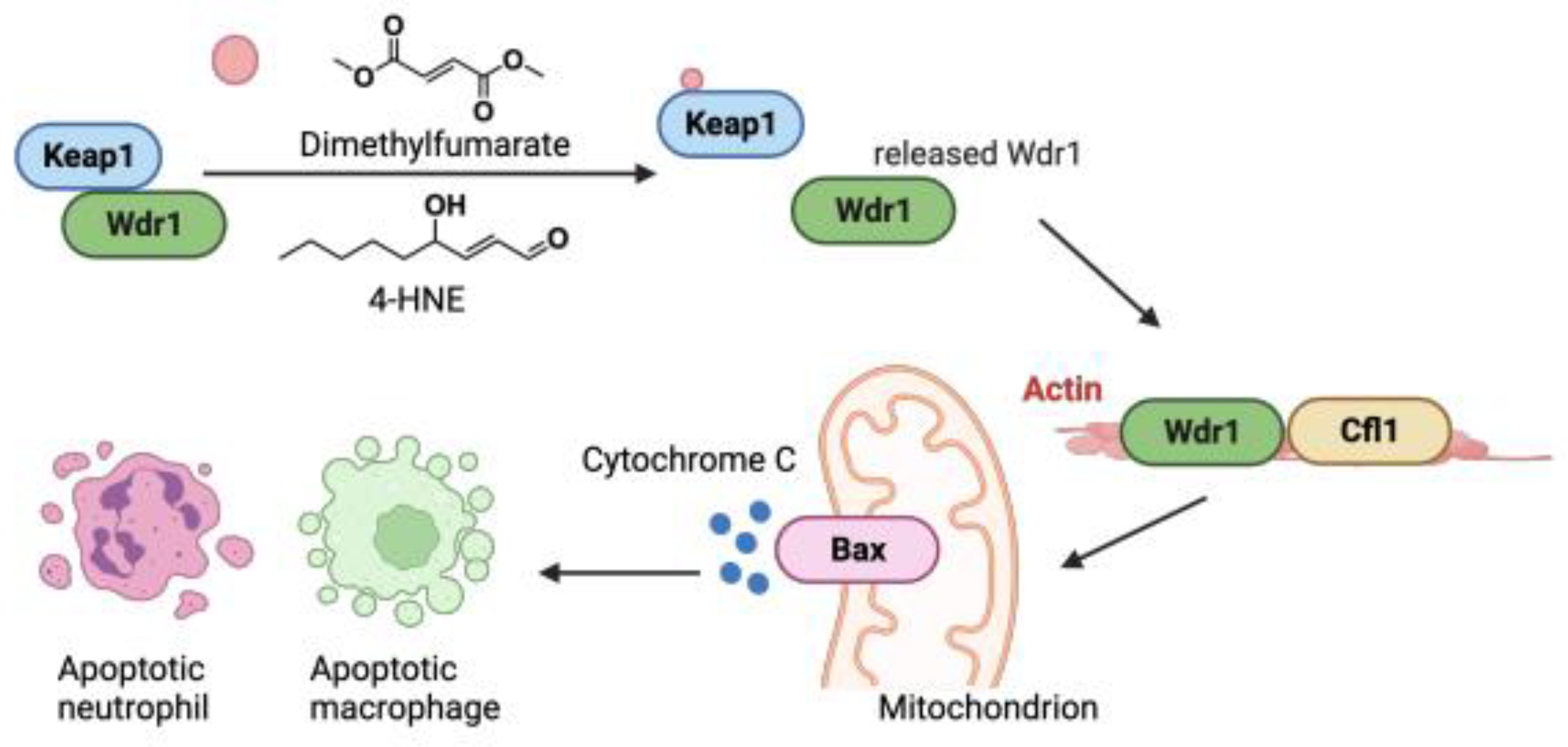

Using a co-immunoprecipitation strategy comparing Keap1 associators before and after electrophile treatment, we recently uncovered that Keap1 can interact with Wdr1 in a manner that, similar to the interactions outlined above, appeared to be competitive with Nrf2. However, contrary to Nrf2-inhibitory proteins, the Keap1/Wdr1 interaction was decreased upon electrophile treatment. Wdr1 release from electrophile-modified Keap1 triggered apoptosis in immune cells in live zebrafish embryos (

Figure 3). No apoptosis was detected elsewhere in other cells in the embryos. These data, that were used to explain how the approved multiple sclerosis drug Tecfidera, and presumably its emerging congeners such as Vumerity and Bafiertam, lower neutrophil counts, potentially explaining the mode of action of such drugs.

[13] These findings also indicate that Keap1 electrophile engagement can radically rewire cellular signaling pathways in a cell-type-specific manner. Indeed, we identified several proteins in addition to Wdr1 whose Keap1 interaction was impeded by electrophile treatment. These proteins could play similarly important contextual roles in marshaling electrophile stress, through a unified electrophile-induced release mechanism. The role of Cul3 (affinity to /expression of) and other competing protein factors could readily help tune the context dependence of such signaling modes.

6. Letting go to relieve stress

In sum, by (re)appreciating that at least to some extent Nrf2 signaling functions through Nrf2 release, we believe that new insights into Keap1-mediated regulation are possible. We do not believe that this is the sole way Keap1 can regulate its targets, but application of this postulate provides a simple screening regimen to identify candidates involved in specific responses to specific small-molecule stress stimuli. Regardless of how various models are reached, performing experiments in live model organisms as much as possible is often proven helpful, with strong back up from results in cell culture models. Furthermore, mounting evidence has shown that using approaches that trigger controlled protein-specific RES modification, in addition to conventional bulk-treatement procedures or approaches that broadly upregulate endogenous stress signaling, proffers new avenues to uncover such nuanced regulatory mechanisms. After all, in light of the (semi)-indiscriminate reactivity of RES as outlined in the beginning of our opinion piece, the unique advantage of precision tools – when deployed alongside appropriate suite of technical and biological controls – is unsurprising.

Author Biographies

Marcus J. C. Long was born in Yorkshire, UK. He was a chemistry scholar at Oxford University, and performed his PhD thesis research at Brandeis University, USA. He subsequently performed postdoctoral research in the Aye research group. He is now a senior postdoctoral researcher at the University of Lausanne. Kuan-Ting Huang was born and raised in Taiwan. He developed methods for chemical labeling of intact antibodies in his BSc and MSc study under the supervision of Prof. Chun-Cheng Lin, and received degrees in Chemistry from National Tsing Hua University. In 2019, he joined the Aye laboratory at EPFL, Switzerland, to study electrophile-regulated signaling pathways and ligand-protein interactions, and to pursue his PhD degree in chemical biology. Yimon Aye was born and raised in Burma. She studied Chemistry at Oxford University (2000-2004), and achieved her doctoral degree in Organic Chemistry at Harvard University in 2009. Her postdoctoral resesarch at MIT focused on the mechanism and regulation of the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase. The Aye laboratory, established in mid-2012, pioneered the use of photocaged electrophiles (REX technologies) as a unique means to map and mine the precision ramifications of protein-electrophile modifications and ensuing signaling in multiple living systems. Contributions made by her laboratory (

https://leago.epfl.ch) have been recognized by international accolades, both from the US and European research communities.

Acknowledgement

Concept and writing: M. J. C. L., Y. A.; figures: K.-T. H. All authors agree to the final version of the manuscript. Funding: EPFL (Y. A.), Novartis (M. J. C. L.).

References

- Horie, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Inoue, J.; Iso, T.; Wells, G.; Moore, T.W.; Mizushima, T.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kasai, T.; Kamei, T.; Koshiba, S.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular basis for the disruption of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction via Hinge & Latch mechanism. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 576. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, L.; Lleres, D.; Swift, S.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Regulatory flexibility in the Nrf2-mediated stress response is conferred by conformational cycling of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 15259–15264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, Y.; Kobayashi, M. Conservation of the Keap1-Nrf2 System: An Evolutionary Journey through Stressful Space and Time. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, J.; Motohashi, H.; Noda, S.; Takahashi, S.; Imakado, S.; Kotsuji, T.; Otsuka, F.; Roop, D.R.; Harada, T.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1-null mutation leads to postnatal lethality due to constitutive Nrf2 activation. Nat Genet 2003, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hall-Beauvais, A.; Poganik, J.R.; Huang, K.T.; Parvez, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Liu, X.; Long, M.J.C.; Aye, Y. Z-REX uncovers a bifurcation in function of Keap1 paralogs. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guschanski, K.; Warnefors, M.; Kaessmann, H. The evolution of duplicate gene expression in mammalian organs. Genome Res 2017, 27, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Wu, J.; Hou, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhong, X. Gene duplication; conservation, and divergence of activating transcription factor 5 gene in zebrafish. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol 2022, 338, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huning, L.; Kunkel, G.R. Two paralogous znf143 genes in zebrafish encode transcriptional activator proteins with similar functions but expressed at different levels during early development. BMC Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Li, L.; Iwamoto, N.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Kaneko, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Eguchi, M.; Wada, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Yamamoto, M. The antioxidant defense system Keap1-Nrf2 comprises a multiple sensing mechanism for responding to a wide range of chemical compounds. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumimoto, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Motomura, S.; Takahashi, D.; Nakayama, K.I. Molecular evolution of Keap1 was essential for adaptation of vertebrates to terrestrial life. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopacz, A.; Kloska, D.; Forman, H.J.; Jozkowicz, A.; Grochot-Przeczek, A. Beyond repression of Nrf2: An update on Keap1. Free Radic Biol Med 2020, 157, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Zhao, K.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Yu, M.; He, M.; Xue, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hu, Y. iASPP Is an Antioxidative Factor and Drives Cancer Growth and Drug Resistance by Competing with Nrf2 for Keap1 Binding. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 561–573 e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, J.R.; Huang, K.T.; Parvez, S.; Zhao, Y.; Raja, S.; Long, M.J.C.; Aye, Y. Wdr1 and cofilin are necessary mediators of immune-cell-specific apoptosis triggered by Tecfidera. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hast, B.E.; Goldfarb, D.; Mulvaney, K.M.; Hast, M.A.; Siesser, P.F.; Yan, F.; Hayes, D.N.; Major, M.B. Proteomic analysis of ubiquitin ligase KEAP1 reveals associated proteins that inhibit NRF2 ubiquitination. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisman, E.; Duarte, P.; Dauden, E.; Cuadrado, A.; Rodriguez-Franco, M.I.; Lopez, M.G.; Leon, R.; KEAP1-NRF2 protein-protein interaction, inhibitors. Design, pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential. Med Res Rev 2023, 43, 237–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hushpulian, D.M.; Kaidery, N.A.; Ahuja, M.; Poloznikov, A.A.; Sharma, S.M.; Gazaryan, I.G.; Thomas, B. Challenges and Limitations of Targeting the Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway for Neurotherapeutics: Bach1 De-Repression to the Rescue. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 673205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamberg, N.; Tahk, S.; Koit, S.; Kristjuhan, K.; Kasvandik, S.; Kristjuhan, A.; Ilves, I. Keap1-MCM3 interaction is a potential coordinator of molecular machineries of antioxidant response and genomic DNA replication in metazoa. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cai, H.; Wu, T.; Sobhian, B.; Huo, Y.; Alcivar, A.; Mehta, M.; Cheung, K.L.; Ganesan, S.; Kong, A.N.; Zhang, D.D.; Xia, B. PALB2 interacts with KEAP1 to promote NRF2 nuclear accumulation and function. Mol Cell Biol 2012, 32, 1506–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Alcivar, A.L.; Ma, J.; Foo, T.K.; Zywea, S.; Mahdi, A.; Huo, Y.; Kensler, T.W.; Gatza, M.L.; Xia, B. NRF2 Induction Supporting Breast Cancer Cell Survival Is Enabled by Oxidative Stress-Induced DPP3-KEAP1 Interaction. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 2881–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Bei, J.X.; Yang, K.; Wu, G.; Huang, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, S. CDK20 interacts with KEAP1 to activate NRF2 and promotes radiochemoresistance in lung cancer cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5321–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, L.; Tan, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J.; Hu, R. FAM117B promotes gastric cancer growth and drug resistance by targeting the KEAP1/NRF2 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camp, N.D.; James, R.G.; Dawson, D.W.; Yan, F.; Davison, J.M.; Houck, S.A.; Tang, X.; Zheng, N.; Major, M.B.; Moon, R.T. Wilms tumor gene on X chromosome (WTX) inhibits degradation of NRF2 protein through competitive binding to KEAP1 protein. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 6539–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.C.; Lin, R.J.; Cheng, J.Y.; Wang, S.H.; Yu, J.C.; Wu, J.C.; Liang, Y.J.; Hsu, H.M.; Yu, J.; Yu, A.L. FAM129B; an antioxidative protein, reduces chemosensitivity by competing with Nrf2 for Keap1 binding. EBioMedicine 2019, 45, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, B.; Nakamura, Y.; Yokoyama, S. Structural analysis of the complex of Keap1 with a prothymosin alpha peptide. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2008, 64, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, S.; Saito, T.; Obata, M.; Koide, R.H.; Ichimura, Y.; Komatsu, M. Negative Regulation of the Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway by a p62/Sqstm1 Splicing Variant. Mol Cell Biol 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.L.; Zhu, C.Y.; Wu, Z.G.; Guo, X.; Zou, W. The oncoprotein HBXIP competitively binds KEAP1 to activate NRF2 and enhance breast cancer cell growth and metastasis. Oncogene 2019, 38, 4028–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, G.D.; Morgan, K.L.; Otis, L.L.; Caltagarone, J.; Gittis, A.; Bowser, R.; Jordan-Sciutto, K.L. Fetal Alz-50 clone 1 interacts with the human orthologue of the Kelch-like Ech-associated protein. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 12113–12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, K.L.; Pikor, L.A.; Chari, R.; Wilson, I.M.; Macaulay, C.E.; English, J.C.; Tsao, M.S.; Gazdar, A.F.; Lam, S.; Lam, W.L.; Lockwood, W.W. Genetic disruption of KEAP1/CUL3 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex components is a key mechanism of NF-kappaB pathway activation in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011, 6, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mealey, G.B.; Plafker, K.S.; Berry, W.L.; Janknecht, R.; Chan, J.Y.; Plafker, S.M. A PGAM5-KEAP1-Nrf2 complex is required for stress-induced mitochondrial retrograde trafficking. J Cell Sci 2017, 130, 3467–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Tang, L.; Li, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Ge, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Nuclear factor p65 interacts with Keap1 to repress the Nrf2-ARE pathway. Cell Signal 2011, 23, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, L.; Li, C.W.; Huang, T.H.; Lam, Y.C.; Xia, W.; Tu, C.; Chang, W.C.; Hsu, J.L.; Lee, D.F.; Nie, L.; Yamaguchi, H.; Wang, Y.; Lang, J.; Li, L.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Mishra, L.; Hung, M.C. Activation of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway by nuclear epidermal growth factor receptor in cancer cells. Am J Transl Res 2014, 6, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Dai, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y. Serine/threonine kinase 3 promotes oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in septic cardiomyopathy through inducing Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 phosphorylation and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 degradation. Int J Biol Sci 2023, 19, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).