Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- age: 8 and 14 years

- -

- BMI > 5th percentile

- -

- PSQ value ≥ 0.33

3. Results

- Comparison analysis of PSQ between the Obesity Group and in Control Group

- Correlation analysis of PSQ with Z-score BMI and respiratory parameters

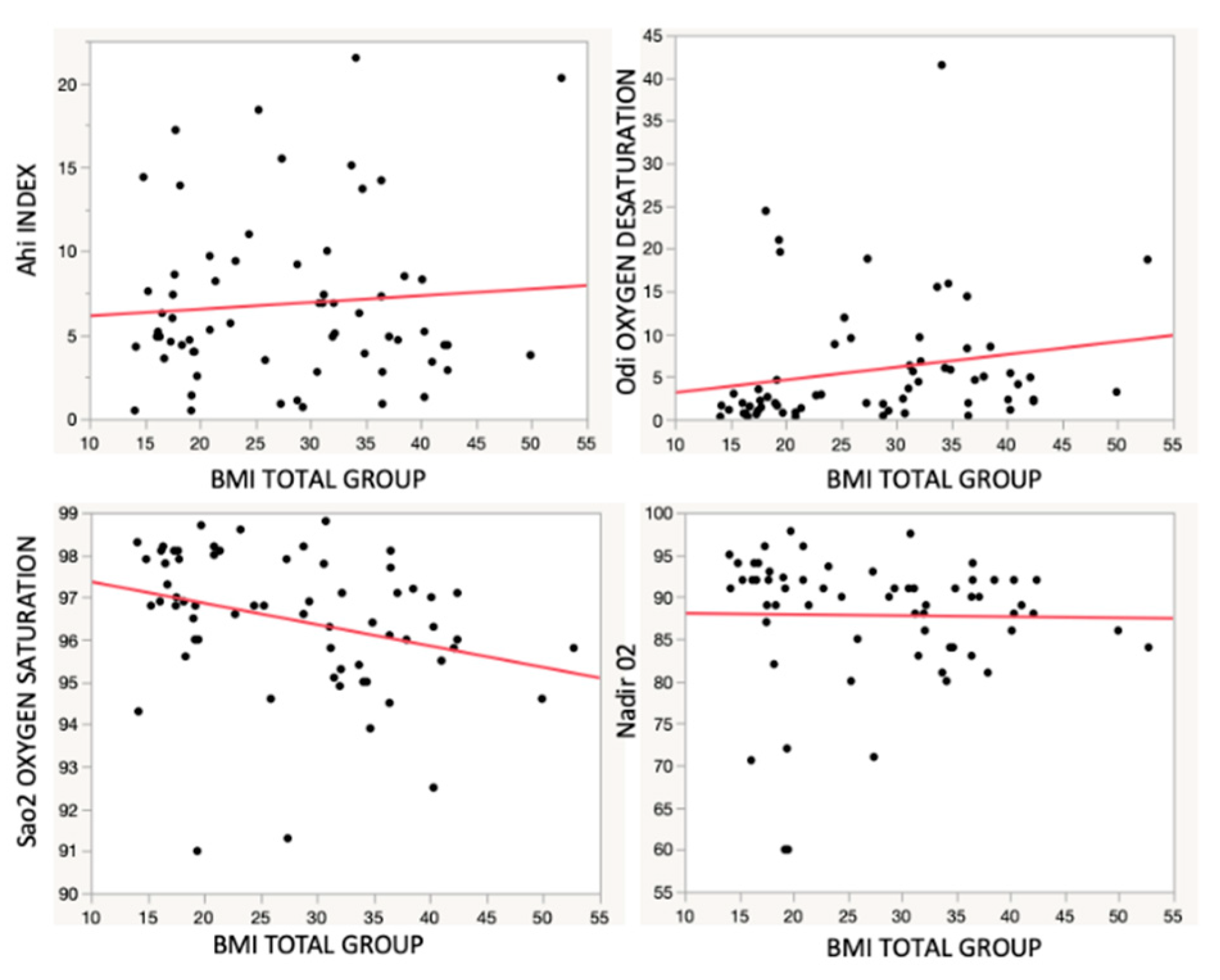

- Correlation analysis between BMI and respiratory parameters

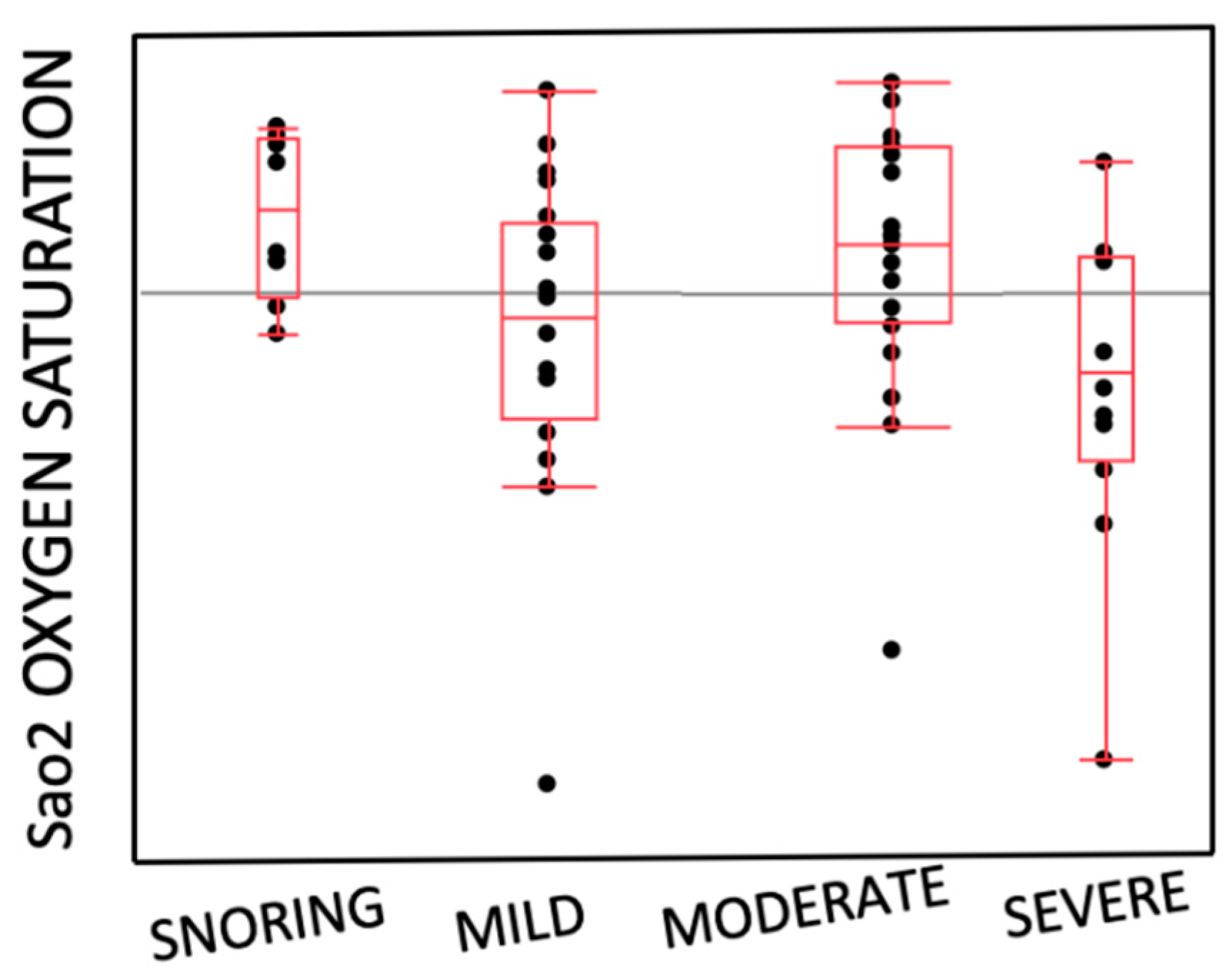

- Distribution of the entity of OSAS and SaO2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- There was no strong correlation between Obesity and OSAS

- -

- No statistically significant correlation was found between the results of PSQ of

- -

- Obesity Group and Control Group and respiratory parameters

- -

- There was correlation between BMI increasing and AHI severity

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Koeler, B. Psych, K. Lushington et al. Obesity and Risk of Sleep Related Upper Airway Obstruction in Caucasian Children. J Clin Sleep Med, 2008, 4(2):129-36. [CrossRef]

- L. Nespoli, A. Caprioglio, L. Brunetti et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in childhood. Early Hum Dev, 2013 , 89 suppl 3:s33/7. [CrossRef]

- IG. Andersen, JC. Holm, P. Homøe. Obstructive sleep apnea in children and adolescents with and without obesity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2019, 276(3):871-878. [CrossRef]

- G. Gulotta, G. Iannella, C. Vicini et al. Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome in Children: State of the Art. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019, 16(18). [CrossRef]

- M. Koeler, Thormaehlen S, Kennedy D et al. Differences in the Association Between Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Among Children and Adolescents. Journal Clinical of Sleep Medicine, 2009, 15;5(6):506-11. [CrossRef]

- MS. Su, HL. Zhang,XH. Cai et al. Obesity in children with different risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea: A community-based study. Eur. J. Pediatr, 2016, 175, 211–220. [CrossRef]

- DW. Beebe. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep, 2006, 29(9):1115-34. [CrossRef]

- RD. Chervin, RA, K.Hedger, J.E.Dillon et al. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ): Validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness and behavioral problems. Sleep Medicine, 2000, 1(1):21-32. [CrossRef]

- RD. Chervin, RA. Weatherly, SL. Garetz et al. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire: Prediction of Sleep Apnea and Outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2007, 133:216-222. [CrossRef]

- CL. Marcus, LJ. Brooks, SD. Ward et al. Technical Report: Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Pediatrics, 2012, 130(3) e714-e755. [CrossRef]

- GR. Umano, G. Rondinelli, M. Luciano et al. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Predicts Moderate-to-Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Children, 2022, 27;9(9):1303. [CrossRef]

- J. Micheal, MD. Sateia. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest, 2014, 146(5):1387-1394. [CrossRef]

- AG. Kaditis, ML. Alonso Alvarez, A. Boudewyns et al. Obstructive sleep disordered breathing in 2- to 18-year-old children: diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J, 2015, 47:69–94. [CrossRef]

- JA.Pena-Zarza, B. Osona-Rodriguez de Torres, JA. Gil-Sanchez et al. Utility of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire and Pulse Oximetry as Screening Tools in Pediatric Patients with Suspected Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Sleep Discord, 2012, 2012:819035. [CrossRef]

- IG. Andersen, JC. Holmb, P. Homøea. Obstructive sleep apnea in children and adolescents with and without obesity. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 2019, 276(3):871-878. [CrossRef]

- YK. Wing, SH Hui, WM Pak et al. A controlled study of sleep related disordered breathing in obese children. Arch Dis Child, 2003, 88:1043-1047. 1047. [CrossRef]

- R. Arens, S. Sin, K. Nandalike et al. Upper airway structure and body fat composition in obese children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med, 2011, 183, 782–787. [CrossRef]

- S. Barlow. Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics, 2007, 120(4):S164-S192. [CrossRef]

- IG. Andersen, JC. Holmb, P. Homøea. Impact of weight-loss management on children and adolescents with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol, 2019, 123, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- S.L Verhulst, H. Franckx, L. Van Gaal, et al. The effect of weight loss on sleep-disordered breathing in obese teenagers. Obesity (silver spring), 2009, 17(6):1178-83. [CrossRef]

- ME. De Felice, L. Nucci, A. Fiori et al. Accuracy of interproximal enamel reduction during clear aligner treatment. Prog Orthod, 2020, Jul 28;21(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, A. Jiaqing, L. Yuchuan et al. A case-control study of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome in obese and nonobese Chinese children. Chest, 2008, 133, 684–689. [CrossRef]

- SE. Brietzke, ES Katz, DW Roberson. Cam history and physical examination reliably diagnose pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypoapnea syndrome? A systematic review of the literarure. Otolaringol Head Neck Surg, 2004, 131:827-32. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, Y. Wu, J. Tai et al. Risk factors of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Journal of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2020, 49(1):11. [CrossRef]

- E. Dekel, L Nucci, T. Weill et al. Impaction of maxillary canines and its effect on the position of adjacent teeth and canine development: A cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 2021, 159(2):e135-e147. [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Lin, Y.X. Su, Y.C. Wu et al. Management of paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent, 2019, 00:1–15. [CrossRef]

- C. Guilleminault, R. Korobkin, R. Winkle. A review of 50 children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Lung, 1981, 159(5):275-87. [CrossRef]

- ML. Alonso-Álvarez, JA. Cordero-Guevara, J. Terán-Santos et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Obese Community-Dwelling Children: The NANOS Study. Sleep, 2014, 37(5):943-9. [CrossRef]

- T. Khosla and CR. Lowe. Indices of obesity derived from body weight and heigh. Nihon Rinsho, 53 Suppl:147-53,1995.

- G. Valerio, C. Maffeis, G. Saggese et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of pediatric obesity: consensus position statement of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology Diabetology and the Italian Society of Pediatrics. Ital J Pediatr, 2018, 31;44(1):88. [CrossRef]

- CL. Marcus, “Pathophysiology of childhood obstructive sleep apnea: current concepts. Respir Physiol, 2000, 119:143–54. [CrossRef]

- CL. Marcus, LJ. Brooks, KA Draper et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Pediatrics, 2012, 130;576.

- G. Gudnadottir, L. Hafsten, S. Redfors et al, “Respiratory polygraphy in children with sleep- disordered breathing. J Sleep Res, 2019, 28:12856.

- M. Cozzani, D. Sadri, L. Nucci et al. The effect of Alexander, Gianelly, Roth, and MBT bracket systems on anterior retraction: a 3-dimensional finite element study. Clin Oral Investig, 2020, 24(3):1351-1357. [CrossRef]

- MJ Sateia. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest, 2014, 146(5):1387-1394. 1387.

| Obesity Group | Control Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 33 | 23 | |

| Male | 19 | 11 | |

| Female | 14 | 12 | |

| Mean Age± Sd (yrs) | 10.47 ± 2.93 | 8.72 ± 2.25 | 0.02 |

| BMI± Sd | 34.95 ± 7.27 | 17.69 ± 2.31 | 0.00 |

| Z-score BMI | 3.77 ± 0.87 | 0.63 ± 0.95 | 0.00 |

| Obesity Group | Control Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSAS SEVERITY | 0.97 | ||

| Snoring (14.3%) | 5 (15.2%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Mild (33.9%) | 11 (33.3%) | 8 (34.7%) | |

| Moderate (32.2%) | 10 (30.3%) | 8 (34.7%) | |

| Severe (19.6%) | 7 (21.2%) | 4 (17.6%) | |

| AHI | 7.04 ± 5.80 | 6.23 ± 4.31 | 0.46 |

| ODI | 9.67 ± 10.30 | 3.72 ± 6.29 | 0.02 |

| Nadir O2 | 86.45 ± 6.76 | 88.94 ± 9.40 | 0.36 |

| SaO2 | 92.67 ± 1.27 | 96.2 ± 1.57 | 0.38 |

| Obesity Group | Control Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | p | |

| PSQ | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Z-score BMI | 0.02 | 1.08 |

| AHI | 0.02 | 1.22 |

| SaO2 | 0.01 | 0.61 |

| ODI | 0.03 | 1.45 |

| Nadir O2 | 0.02 | 1.13 |

| r2 | p | |

|---|---|---|

| AHI | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Sa O2 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| ODI | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| NADIR O2 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).