1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorders affect around 1% of the population worldwide and are usually highly impairing, underscoring the need for early and adequate treatment at target abilities (Lord et al., 2018). Socio-Communication impairments are a core feature required for the diagnosis of ASD, and one of the earliest signs (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). Moreover, eye contact and joint attention skills are the base for socio-communication abilities, and essential to the early brain development process (Mundy, 2018).

Most early treatment programs for children with ASD are based on the acquisition of eye contact and joint attention as prerequisites for other socio-communicative skills and spoken language (Mundy, 2018). Early intervention is critical to address early social deficits and avoid a cascade of impairments in learning and development (Dawson et al., 2012; Mundy & Burnette, 2005). For these skills to be installed and generalized, it is essential that this training is individualized, early and intensive, affecting all the child's social contexts. One of the most effective treatments for ASD is Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) (Peters-Scheffer et al., 2011; Reichow et al., 2013; Steinbrenner et al., 2020; Virues-Ortega, 2010; Warren et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2015). However, due to its cost and the need for specialist professionals, it is inaccessible to most of the population (Beaudoin et al., 2014).

Discrete Trial Training (DTT), Prompting, Parental Training, and Video Modelling are some evidence-based practices derived from ABA (Steinbrenner et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2015). These strategies allow the use of interventions designed to avoid errors or incorrect answers, which is known as errorless learning. The contents are presented in a controlled and systematic way, being broken down into small “discrete” components in the case of DTT, and into a hierarchy of “tips” in Prompting (Green, 2001). ABA requires that the learned behavior must be recorded through direct and continuous observation by those delivering it, whether they be specialists or parents/caregivers (Green & Johnston, 2009; Johnston, 1979; Johnston & Pennypacker, 1993; Johnston et al., 2020).

Good outcomes through ABA interventions requires high intensity (number of hours per week) and the long durations (in years, for example) (Linstead et al., 2017), CASP, 2020. However, it can be expensive for implementation in low and middle income countries (Lee & Meadan, 2021). Therefore, the use of parental training has emerged as a method to ensure the stimulation of children with ASD in a natural environment, and to guarantee the maximum exposure to ABA therapy (Dawson-Squibb et al., 2020; Schultz et al., 2011). Parents have many opportunities to train these skills throughout the day in different contexts, facilitating generalization. There are an increasing number of studies in the literature related to the effectiveness of parental training in respect of the main symptoms of autism, but the results could be conflicting (Beaudoin et al., 2014; Green et al., 2010; Nevill et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2012). In addition, most of them do not describe performance through the entire process, making it difficult to understand the factors related to the acquisition of new behaviors. Consequently, the ABA’s analytic dimension is unable to be evaluated (Baer et al., 1968, 1987; Green & Johnston, 2009; Johnston, 1979; Johnston & Pennypacker, 1993; Johnston et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, parental training studies based on ABA have been growing along with the importance and scope of treatment models using technological resources like video modelling (Dai et al., 2018; Law et al., 2018; McGarry et al., 2020; Vismara et al., 2013; Wainer & Ingersoll, 2015). Its use can promote the assistance of patients with ASD, making it easier for families to deliver effective care and decrease treatment costs.

There is a need to facilitate access to less costly evidence-based intervention for this population (Wetherby et al., 2018), especially for the most severe profile associated with intellectual disability. This study aimed to test the feasibility and efficacy of an intervention model to acquire eye contact and joint attention in children with ASD by means of a parental intervention using video modelling, and to investigate the clinical factors related to the results.

2. Materials and Methods

This study data was extracted from a pilot, multicenter, single-blinded 22-week randomized clinical trial of a parent-mediated intervention group using Video Modelling conducted between January and November 2014. Further methods details can be found elsewhere (citation removed for blind review).

Participants were sixty-seven families with children aged between 3 and 6 years and 11 months with ASD and ID and were enrolled in the RCT from three ASD centers: i) the Social Cognition Clinic of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (TEAMM/UNIFESP); ii) the ASD Program of the Universidade de São Paulo (PROTEA/HC), and iii) the Developmental Disorders Post-Graduation Program of the Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie (TEA-MACK). Randomization: Sixty-seven families were randomized, and thirty-four families were allocated to the intervention group and thirty-three to the control group. However, one case from the control group had to be ruled out later due to an error in counting ADI-R's diagnostic criteria. In this study only the intervention group (34 participants) was analyzed.

The inclusion criteria for the study were: children with an ASD diagnosis according to the Brazilian version of the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R), IQ between 50 and 70, and the caregiver should have at least eight years of schooling and be able to read the intervention material. The exclusion criteria were children with uncontrolled epilepsy, those receiving intensive behavioral intervention (>10 hours per week), children whose main caregiver had an ASD diagnosis, or those who did not have a DVD player at home. Before data collection, a parent or legal guardian signed a written informed consent, and all participants received help to attend all intervention and evaluation sessions during the training. The study was approved for the Ethical Committee of Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo (UNIFESP) under protocol number (information removed for blind review).

2.1. Professional Training and Development of Materials for Parental Training

All the professionals involved in the evaluation were trained to apply the specific instruments and were blind to the outcome assessments. The supervisory team was composed only by behavior analysis experts and produced all the training material, as described in (citation removed for blind review).

2.2. Measurements

1. The Brazilian version of the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R) was used as the diagnostic instrument for all children at baseline. The ADI-R is a 93-item structured interview conducted with parents to measure four domains: reciprocal social interaction, communication, language, and patterns of behavior. The Brazilian version of the ADI-R was adapted and validated by Becker et al. (2012). A trained psychologist supervised the administration of all interviews.

2. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP): Socioeconomic level (SES) was assessed by a questionnaire developed by the Brazilian Association of Research Companies to evaluate a families’ socioeconomic level (SES). This instrument was applied at baseline and is one of the most used in Brazil and considers, among other factors, the number of home appliances and the education level of the head of the household. Total scores determine the socioeconomic status of families: social class A: scores 100-45; B: 44-29; C: 28-17 and D/E: 16-0, where the higher the score, the higher the socioeconomic level (Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa, 2014).

The following two instruments were applied before and after (at week 28) the intervention by independent evaluators who were blind to the outcome assessments. Parents were aware of the treatment assignment.

1. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale – First Edition (VABS): a structured interview was applied to the caregivers to assess the following domains: socialization, communication, daily living, and motor skills. Age equivalent scores and standard scores (M=100; SD=15) are provided for each domain, and scores across domains can be combined to create an overall Adaptive Behavior Composite Score (Sparrow et al., 1984). In this study, adaptive skills were assessed using age equivalent scores because they had more sensitivity in young children with ASD and ID during the progression of the intervention (Gabriels et al., 2007).

2. The Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Test (SON 2½-7): a non-verbal measure of IQ comprising six tests (categories, analogies, scenarios, stories, mosaics, and patterns). This battery was standardized and validated for the Brazilian social and cultural context (Laros et al., 2010).

2.3. Parental Training by Video Modelling Based on ABA

Three parental training groups with around eleven participants in each center, received 22 weeks, 90-minute sessions. Two of them together with their children, to make corrections, if necessary, to the procedures to be followed and the remaining only with the caregiver. All procedures described below took place simultaneously and identically at the three sites.

The data was collected by the

Record Sheets which were developed specifically for this study by the research team specialized in behavior analysis. It allowed caregivers to record all attempts to produce eye contact and joint attention behaviors, and what level of help was used in each trial. Each training level used a different sheet. The sheet contained two blocks with space to record the details for 18 attempts totalizing 36 attempts in a day (Examples of these sheets are contained in the

supplementary materials). For each attempt, caregivers were instructed to record the level of help used. The levels followed a prompting hierarchy starting with a high level of prompting. They were: full physical prompt (FPP); partial physical prompt (PPP); gestural prompt (GP); and independent (I).

Each parental training sessions was organized as follows: 1) the video was presented to the groups of parents; 2) the record sheets from the previous week were analyzed and checked; 3) the DVD and record sheet for the next level of training were handed out or doubts about the videos were clarified with the parents through the previous videos and 4) participants signed the attendance list at the end of the session. Any caregiver who had missed the previous week’s session was given the audio-visual material and the record sheets in addition to that week's material.

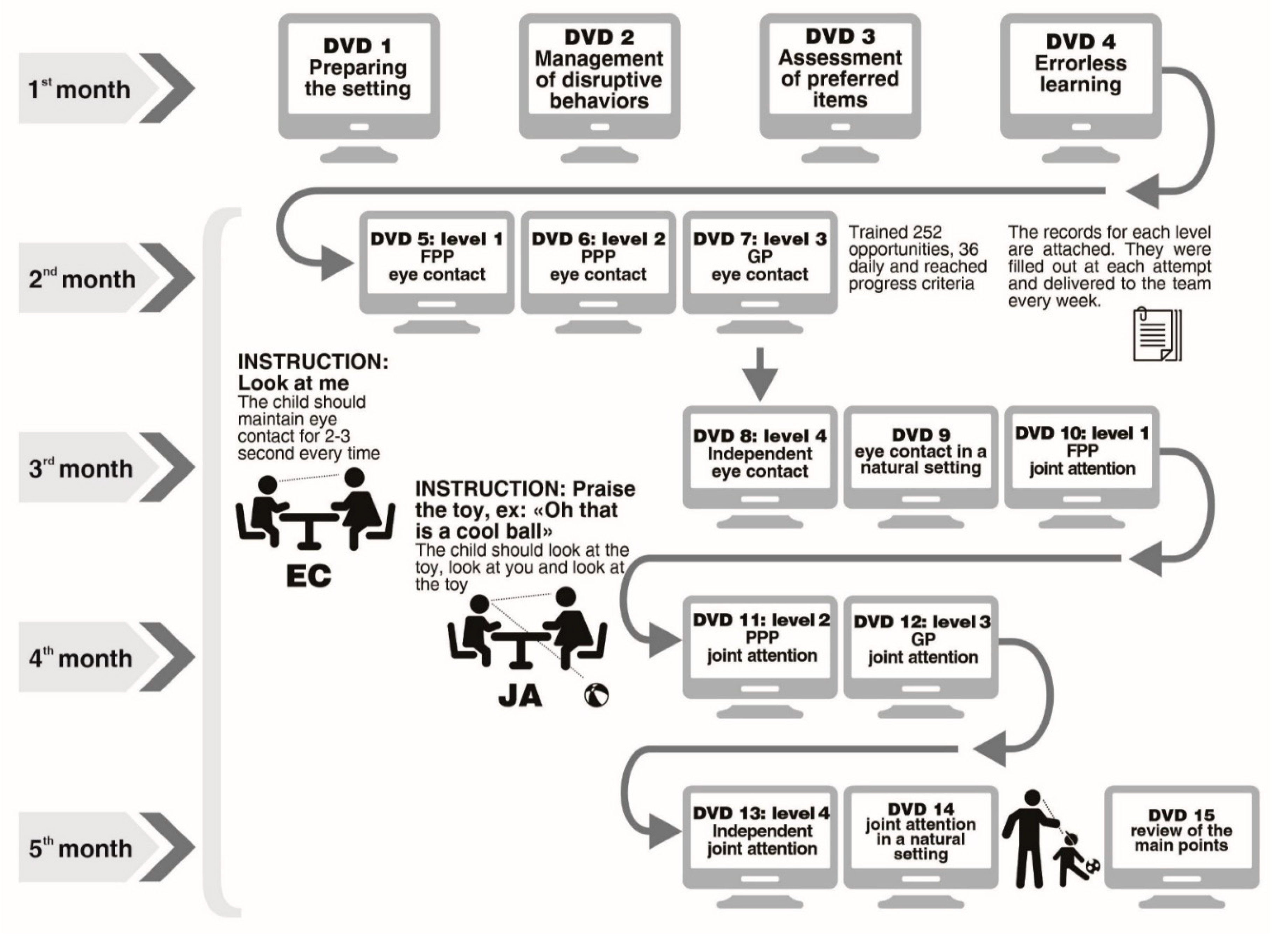

The ABA specialized professionals produced 15 videos for this clinical trial. In respect of the video modelling methods applied in this study, we delineated structured and hierarchical prompts to be taught to the parents. The first four videos offered the theoretical-practical basis for the training itself. All of them contained objectives and descriptions of procedures, instructions to complete the registration sheets, and how to apply the activities to the children. The remaining 10 videos contained the sequence of prompt to teach eye contact and joint attention, and the last one was a review. At each session, the families received a copy of the video shown that day to practice at home. More details about videos contents were described elsewhere (citation removed for blind review).

The parents were instructed to watch the DVD at home and apply the procedures twice a day, at different times, during the 22 weeks, from Monday to Sunday. The caregiver registered on the record sheet the level of help (FPP, PPP,GP or I) used in each attempt.

The parental training methodological procedures are summarized in

Figure 1.

Initial training was on acquiring eye contact skills, which is considered a prerequisite for joint attention acquisition, and focused on triangulation and eye-gazing.

The DVD procedures were related to errorless learning and DTT practices with essential components such as reinforcement and prompts to acquire both skills. The most-to-least (MTL) prompt (starting with a high level of prompting) was selected for the acquisition phase due to the sample being composed of ASD children with intellectual disabilities. The prompting hierarchy was: full physical prompt (FPP)→ partial physical prompt (PPP)→ gestural prompt (GP)→ independent (I). This method used a “fading process”, starting with a physical prompt, such as a soft touch on the face; then a gesture, for example indicating where the eye should be directed, until the ability became independent.

During this training period, parents were given the task of performing two blocks of nine trials twice per day, so that the child was exposed to 36 daily opportunities to practice the skills. There was a two-minute interval between each block. The parent/guardian practiced the activity with the child throughout the week, and after mastering the attempts at level 1 (FPP), the family member received the level 2 (PPP) video and record sheet and continued until the child could independently perform these behaviors. Therefore, caregivers first learned about FPP and were instructed to register 36 attempts per day of this level of support. Then, they learned about PPP and registered which type of prompt the child needed for each attempt. From this point on, as caregivers learned about different types of prompts, they were instructed to try to give less support and offer higher levels of support only as needed.

Data analyzed in this study include only the record sheets for DTT practices with most-to-least prompt strategy.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The outcome measures of the study were recorded as follows: eye contact - full physical prompt; eye contact - partial physical prompt; eye contact- gestural prompt; and independent eye contact, as measured by the eye contact record sheets: and joint attention – full physical prompt; joint attention – partial physical prompt; joint attention - gestural prompt; and independent joint attention, as measured by the joint attention record sheets. Sex, age, age equivalent scores of the Vineland Socialization domain, IQ measures, training (total number of completed record sheets for each family, used as a proxy of adherence) and time (days of training) were treated as covariates.

Four generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to evaluate the four graded measures of both eye contact and joint attention (i.e., full physical prompt, partial physical prompt, gestural prompt, and independent). The GEEs’ working correlation matrix used was the first-order autoregressive with a robust estimator. The model underlying the GEEs was linear because the scores for each one of the four assessed parameters were considered as continuous variables. All the covariates were added to the model. All the models were run using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp, 2016) and the adopted significance level was 0.05. In this paper, we will be using only the data of the intervention group because our goal was to analyze the skill’s acquisition progress inside the experimental group.

3. Results

This study comprised 34 children with ASD and ID who received the Intervention Program, 70.6% were males the mean age was 4.76 years old, the mean IQ 60, and the mean socio-economic level 24.91 (ABEP).

The data collected from the eye contact record sheets and joint attention record sheets provided the outcome measures that will be described in the following paragraphs.

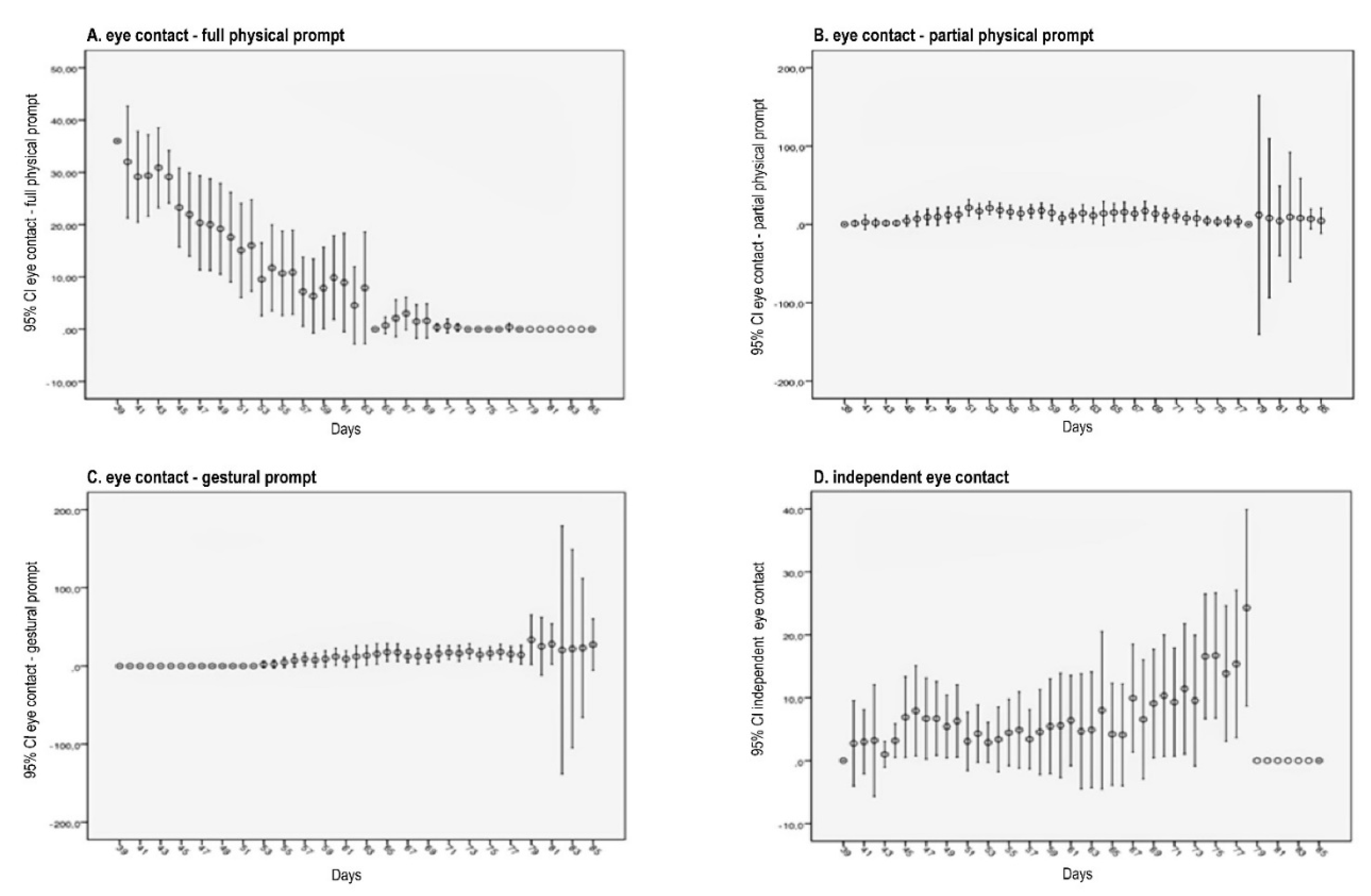

Figure 2 depict the means of attempts (with 95% confidence intervals) across the time (day) for the four outcomes, full physical prompt (FPP), partial physical prompt (PPP), gestural prompt (GP), and independent (I) in respect of eye contact. The number of attempts could vary from zero (if the family didn´t apply the protocol at a given day) to 36 (maximum number of attempts per day).

Table 1 shows the effects of all covariates on the four assessed outcomes. Among the four measures, there was a reduction of 0.862 (p-value <0.001) in total eye contact – full physical prompt over the period of the intervention and an increase in the average number of gestural eye contact prompts across de time of 0.537 (p-value=0.029). In terms of sex, we observed that for eye contact – partial physical prompt, males required, on average, less partial physical eye contact prompt than females across the whole study. For the other outcomes, there was no statistically significant differences between sexes.

There was an association between training received (number of completed record sheets per family) and the number of partial physical prompt. The more sections, the greater number of partial physical prompt (Β=0.132, p-value <0.001).

IQ and age were positive statistically significant predictors of the number of gestural prompts, (Β=0.442, p-value <0.001) and (Β=0.277, p-value <0.001), respectively.

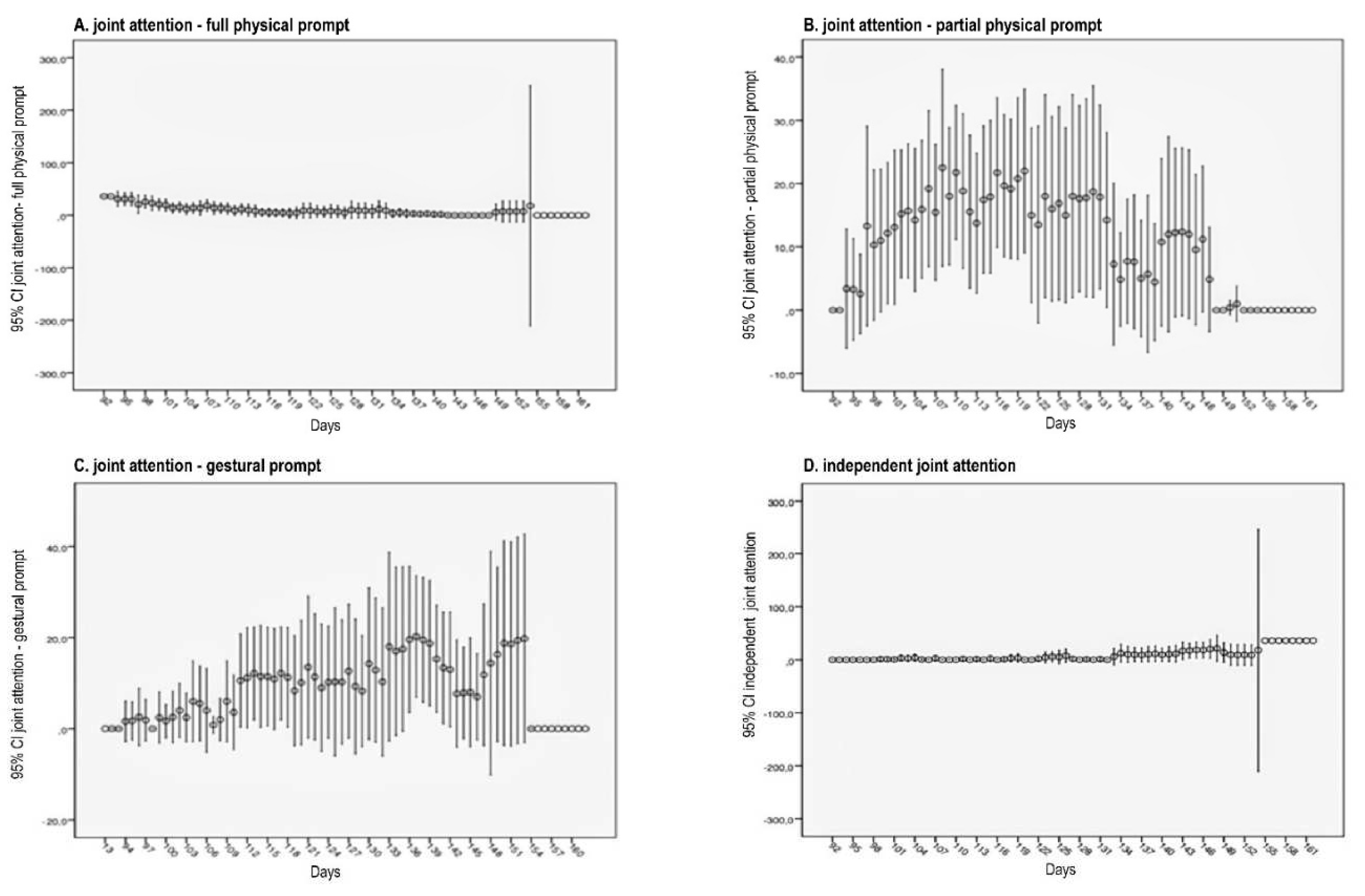

Figure 3 depict the means of attempts (with 95% confidence intervals) across the period of the intervention (days) for the four outcomes in respect of joint attention. The number of attempts could vary from zero (if the family didn´t apply the protocol at a given day) to 36 (maximum number of attempts per day).

Table 2 shows that the number of joint attention full physical prompts decreased over the period of the intervention (Β=-0.449, p-value<0.001), and the number of independent joint attention increased (Β=0.251, p-value<0.001). Other statistically significant effects were the VABS scores (Β=0.218, p-value=0.006), IQ (Β=0.354, p-value = 0.008), and age (Β=0.242, p-value = 0.005), which were all positively correlated with independent joint attention. This means that the higher the VABS scores, the more independent behavior was observed. In the same way, we found that the higher the IQ, the more independence and, lastly, the older, the more independence. The number of joint attention partial physical prompts and gestural prompts was not statistically significant, (Β=-0.066, p-value = 0.258, B=0.162, p-value=0.107, respectively).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the process of children with ASD and ID acquiring eye contact and joint attention through video modelling in a parental intervention group. Overall, we found a progressive reduction in the level of prompt required over the period of the intervention for both target skills, eye contact and joint attention.

This demonstrates that parents can be transformative agents and have a significant role in the treatment of their children with ASD. Their ability to implement therapies (under experienced supervision) and to achieve changes in their children's abilities have increasingly been documented in recent years (Bearss et al., 2015; Beaudoin et al., 2014; Dawson-Squibb et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2017; Hardan et al., 2015; Karst & Van Hecke, 2012; O’Donovan et al., 2019; Parsons et al., 2017; Stahmer et al., 2019; Tellegen & Sanders, 2014). This is particularly important in situations in which there is a lack of trained professionals (Beaudoin et al., 2014; Dawson-Squibb et al., 2020).

Eye contact is considered a prerequisite skill for joint attention (Clifford & Dissanayake, 2008), so it is essential that it is learned well, so that more complex derived skills can be acquired more quickly and at the highest possible level (Bosch & Hixson, 2004; Monlux et al., 2019; Pelaez & Monlux, 2018; Rosales-Ruiz & Baer, 1997). During the process of acquiring the skill of eye contact, there was a gradual, statistically significant reduction in the need for physical prompts, and an increase in gestural prompts. This can be regarded as a reflection of progress as gestural prompts are more difficult to execute and are less invasive than physical prompts. It allows the child to respond following only a gesture and, therefore, generates an increase in independence. As our sample comprised children with ASD and ID, the most-to-least procedure was especially useful in teaching skills, maximizing learning capacity (Cengher et al., 2016). The Gulsrud hypothesis states that early interventions focused on prelinguistic and gesture repertoires for children with ASD may change the joint attention trajectory over time (Gulsrud et al., 2014). In this sense, the intervention model described in this study seems to produce this type of long-term benefit.

A robust finding in this study was a positive association between the intervention and joint attention ability. Although ABA is considered the most effective treatment for children with ASD, there is still a great deal of debate about the ideal treatment dosage, that is, its intensity and duration, to achieve the best results. Linstead et al. (2017) assessed the influence of these two factors separately on eight main outcomes (academic, adaptive, cognitive, executive function, language, motor, play, and social skills) in children with ASD. A robust linear relationship between skill acquisition and both treatment duration and intensity were demonstrated for all the factors, although the dose-response relationships were greatest in academic and language domains (Linstead et al., 2017).

Families can have an important role in increasing treatment dosage, with many developmental and behavioral studies reinforcing the central role of the family in the treatment of children with ASD (Magan-Maganto et al., 2017; Narzisi et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2019; Steinbrenner et al., 2020; Wetherby et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2015). Parental training increases the number of hours of treatment the children receive by incorporating stimulation strategies into routine activities. This decreases the need for a sizeable, specialized team, making treatment less costly and easier to apply. These studies, like ours, show the potential for improving the developmental trajectory of children with ASD by involving parents at an early stage in the use of stimulation techniques to develop socio-communicative engagement (Wetherby et al., 2018).

Our findings also show that the acquisition of independent joint attention was positively associated with higher IQ levels, older age, and better social functionality. Overall, the most documented predictors of better prognosis in children with ASD are IQ level, social functionality, and communicative ability (Billstedt et al., 2005; Farley et al., 2009; Fountain et al., 2012; Howlin et al., 2004; Howlin et al., 2013; Kirby et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2014).

It is known that individual abilities at baseline to some extent predict outcomes in early intensive interventions in ASD (Ben-Itzchak & Zachor, 2007). Higher initial cognitive levels and fewer measured early social interaction deficits promote better acquisition of skills in developmental areas, receptive and expressive language, and play skills. Moreover, the cognitive functioning profile of children with ASD before intervention programs predicts the growth rates of the participants (Tiura et al., 2017). A recent clinical trial with parental training in children with ASD and disruptive behaviors identified levels of cognitive potential (an IQ greater than or less than 70) as one of the determining factors for functional improvement (Scahill et al., 2016). One of the most consistent findings in longitudinal studies about childhood predictors of better outcomes in ASD adulthood is intellectual functioning (Farley et al., 2009; Howlin et al., 2013).

Despite the great number of studies in the literature showing better results from early interventions (Ben-Itzchak & Zachor, 2007; Eikeseth et al., 2007; Gabriels et al., 2007; Granpeesheh et al., 2009) we found a controversial positive association between age and joint attention acquisition. This finding is not in line with most of the literature. We hypothesize that this may be explained because older children are more likely to learn due to the neuronal maturation process itself (Piven et al., 2017) or that they may be benefitting from repetition of the experiences in their longer lives. Further studies need to be undertaken to better understand the issue of age.

In our study, males required, on average, fewer partial physical prompts in respect of eye contact, than females. Findings on this subject are contradictory, with some studies reporting that ASD is more severe cases in girls than boys, while do not confirm these results (Hartley & Sikora, 2009; Idring et al., 2012; Lord & Schopler, 1985; Mattila et al., 2011; Volkmar et al., 1993; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2012). However, there was no statistically significant difference between sex in our data concerning initial IQ. Further investigation is required to understand if sex, regardless of severity, can impact skills acquisitions.

According to Wetherby et al. (2018) the main gaps in the evidence base of interventions for toddlers with ASD were in respect of: (1) the level of intensity needed to change development trajectory. Current recommendations are for intervention of 15-25h per week, but this is unfeasible for any public system, especially in LMIC; (2) the need to increase the number and intensity of parental training sessions to achieve results in children, thereby reducing the need for more intensive interventions in the future; and (3) reliable and meaningful outcome measures for toddlers with ASD, particularly in respect of documenting changes in the natural environment. All these factors were considered in the current study, since it is a multicenter controlled clinical trial using parental training, an intensive model, and direct assessments to measure outcomes in the children, as well as using a group format. The advantages of training parents in group sessions are that they provide an opportunity for the participants to share their experiences and offer emotional support to people with similar problems, and they also optimize the use of resources and time of the specialized professionals.

Recorded material can be a valuable resource to help families of children with ASD, especially in the current pandemic context. In the last few years, the advance of videos and other techniques has been used to offer greater support and information to parents, especially those who do not have easy access to services (Dai et al., 2018; Law et al., 2018; McGarry et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2017; Steinbrenner et al., 2020; Vismara et al., 2013; Wainer & Ingersoll, 2015; Wong et al., 2015). In 2016, a review of the use of video modelling demonstrated preliminary positive findings in the treatment of people with ASD but suggested that more extensive studies with more cases were needed to confirm the effectiveness of this technique (Hong et al., 2016).

The use of record sheets to constantly monitor the participants’ performance is standard practice in ABA research, but usually only in single-subject studies or series of few cases. This study used a randomized clinical trial, a research methodology traditionally used with larger samples and pre- and post-intervention measurements. This allowed the use of methods already tested in single case/small groups to be assessed in larger groups, to develop evidence-based practices and answer a number of questions in respect of the methodology for this patient profile (Smith, 2013). The five practices used in this study - Discrete Trial Training, Parent-Implemented Interventions, Prompting, Reinforcement, and Video Modeling (Steinbrenner et al., 2020) are all practices that are possible to implement in low-income families and the public health sector. This gives a more robust scientific and methodological relevance to the findings, increasing confidence in the use of this type of therapy for this profile of participants.

Finally, most studies stress the need for behavioral interventions with a long duration and a great number of hours in more severe cases of ASD, especially with associated ID (de Vries, 2016; Tiura et al., 2017; Volkmar et al., 2014). One of our study's strongest points is to demonstrate that children with ASD and ID were able to acquire the target behaviors through a relatively short-term parental intervention even though their children had IQs in the lower range.

Despite of the strengths of the study, some limitations should be mentioned: (1) lack of direct evaluation of the children, ideally using the ADOS; (2) absence of an active control group, and (3) of the confirmation that the parents followed the procedures because data was based on analysis of sheets.

In conclusion, this is an original study carried out in a family-centered, group format with patients with ASD and ID in need of treatment that produced positive results. Because it is relatively short term and free, it can be used in low- and middle-income countries and communities with limited access to health services and make a valuable contribution to improving public health care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Daniela Bordini, Ana Moya and Cristiane Paula; Formal analysis, Cristiane Paula and Leila Bagaiolo; Methodology, Daniela Bordini, Ana Moya and Leila Bagaiolo; Project administration, Cristiane Paula; Writing – review & editing, Daniela Bordini, Ana Moya, Graccielle Cunha, Cristiane Paula, Décio Brunoni, Helena Brentani, Sheila Caetano, Jair Mari and Leila Bagaiolo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Agency FAPESP and Maria Cecília Souto Vidigal Foundation [Grant number 2012/51584-0]; the NGO Autismo & Realidade that gave support for the administration of the grant; and all the TEAMM, HC and Mackenzie staff who worked on data collection, as well as the participating families and patients. JJM is a senior researcher from the National Research Council (CNPq). We also thank Professor Hugo Cogo-Moreira PhD for his support in the statistical analysis.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2014). DSM-5: Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais (5 ed.). Artmed.

- Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. (2014). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil. http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil.

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal, 1(1), 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1987). Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal, 20(4), 313-327. [CrossRef]

- Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., McAdam, D. B., Butter, E., Stillitano, C., Minshawi, N., Sukhodolsky, D. G., Mruzek, D. W., Turner, K., Neal, T., Hallett, V., Mulick, J. A., Green, B., Handen, B., Deng, Y., Dziura, J., & Scahill, L. (2015). Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(15), 1524-1533. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, A. J., Sebire, G., & Couture, M. (2014). Parent training interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res Treat, 2014, 839890. [CrossRef]

- Becker, M. M., Wagner, M. B., Bosa, C. A., Schmidt, C., Longo, D., Papaleo, C., & Riesgo, R. S. (2012). Translation and validation of Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) for autism diagnosis in Brazil. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 70, 185-190. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-282X2012000300006&nrm=iso.

- Ben-Itzchak, E., & Zachor, D. A. (2007). The effects of intellectual functioning and autism severity on outcome of early behavioral intervention for children with autism. Res Dev Disabil, 28(3), 287-303. [CrossRef]

- Billstedt, E., Gillberg, I. C., & Gillberg, C. (2005). Autism after adolescence: population-based 13- to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. J Autism Dev Disord, 35(3), 351-360. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, S., & Hixson, M. D. (2004). The final piece to a complete science of behavior: Behavior development and behavioral cusps. The Behavior Analyst Today, 5(3), 244-254. [CrossRef]

- Cengher, M., Shamoun, K., Moss, P., Roll, D., Feliciano, G., & Fienup, D. M. (2016). A Comparison of the Effects of Two Prompt-Fading Strategies on Skill Acquisition in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Behav Anal Pract, 9(2), 115-125. [CrossRef]

- Clifford, S. M., & Dissanayake, C. (2008). The early development of joint attention in infants with autistic disorder using home video observations and parental interview. J Autism Dev Disord, 38(5), 791-805. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y. G., Brennan, L., Como, A., Hughes-Lika, J., Dumont-Mathieu, T., Rathwell, I. C., Minxhozi, O., Aliaj, B., & Fein, D. A. (2018). A Video Parent-Training Program for Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Albania. Res Autism Spectr Disord, 56, 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Squibb, J. J., Davids, E. L., Harrison, A. J., Molony, M. A., & de Vries, P. J. (2020). Parent Education and Training for autism spectrum disorders: Scoping the evidence. Autism, 24(1), 7-25. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G., Bernier, R., & Ring, R. H. (2012). Social attention: a possible early indicator of efficacy in autism clinical trials. J Neurodev Disord, 4(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- de Vries, P. J. (2016). Thinking globally to meet local needs: autism spectrum disorders in Africa and other low-resource environments. Curr Opin Neurol, 29(2), 130-136. [CrossRef]

- Eikeseth, S., Smith, T., Jahr, E., & Eldevik, S. (2007). Outcome for children with autism who began intensive behavioral treatment between ages 4 and 7: a comparison controlled study. Behav Modif, 31(3), 264-278. [CrossRef]

- Farley, M. A., McMahon, W. M., Fombonne, E., Jenson, W. R., Miller, J., Gardner, M., Block, H., Pingree, C. B., Ritvo, E. R., Ritvo, R. A., & Coon, H. (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Res, 2(2), 109-118. [CrossRef]

- Fountain, C., Winter, A. S., & Bearman, P. S. (2012). Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. PEDIATRICS, 129(5), e1112-1120. [CrossRef]

- Gabriels, R. L., Ivers, B. J., Hill, D. E., Agnew, J. A., & McNeill, J. (2007). Stability of adaptive behaviors in middle-school children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(4), 291-303. [CrossRef]

- Granpeesheh, D., Dixon, D. R., Tarbox, J., Kaplan, A. M., & Wilke, A. E. (2009). The effects of age and treatment intensity on behavioral intervention outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(4), 1014-1022. [CrossRef]

- Green, G. (2001). Behavior Analytic Instruction for Learners with Autism: Advances in Stimulus Control Technology. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16(2), 72-85. [CrossRef]

- Green, G., & Johnston, J. M. (2009). Licensing behavior analysts: risks and alternatives. Behav Anal Pract, 2(1), 59-64. [CrossRef]

- Green, J., Charman, T., McConachie, H., Aldred, C., Slonims, V., Howlin, P., Le Couteur, A., Leadbitter, K., Hudry, K., Byford, S., Barrett, B., Temple, K., Macdonald, W., Pickles, A., & Consortium, P. (2010). Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 375(9732), 2152-2160. [CrossRef]

- Gulsrud, A. C., Hellemann, G. S., Freeman, S. F., & Kasari, C. (2014). Two to ten years: developmental trajectories of joint attention in children with ASD who received targeted social communication interventions. Autism Res, 7(2), 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B. D., Orton, E. L., Adams, C., Knecht, L., Rindlisbaker, S., Jurtoski, F., & Trajkovski, V. (2017). A Pilot Study of a Behavioral Parent Training in the Republic of Macedonia. J Autism Dev Disord, 47(6), 1878-1889. [CrossRef]

- Hardan, A. Y., Gengoux, G. W., Berquist, K. L., Libove, R. A., Ardel, C. M., Phillips, J., Frazier, T. W., & Minjarez, M. B. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of Pivotal Response Treatment Group for parents of children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 56(8), 884-892. [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S. L., & Sikora, D. M. (2009). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: an examination of developmental functioning, autistic symptoms, and coexisting behavior problems in toddlers. J Autism Dev Disord, 39(12), 1715-1722. [CrossRef]

- Hong, E. R., Ganz, J. B., Mason, R., Morin, K., Davis, J. L., Ninci, J., Neely, L. C., Boles, M. B., & Gilliland, W. D. (2016). The effects of video modeling in teaching functional living skills to persons with ASD: A meta-analysis of single-case studies. Res Dev Disabil, 57, 158-169. [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 45(2), 212-229. [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P., Moss, P., Savage, S., & Rutter, M. (2013). Social outcomes in mid- to later adulthood among individuals diagnosed with autism and average nonverbal IQ as children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 52(6), 572-581 e571. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24. In.

- Idring, S., Rai, D., Dal, H., Dalman, C., Sturm, H., Zander, E., Lee, B. K., Serlachius, E., & Magnusson, C. (2012). Autism spectrum disorders in the Stockholm Youth Cohort: design, prevalence and validity. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e41280. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. M. (1979). On the relation between generalization and generality. Behav Anal, 2(2), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. M., & Pennypacker, H. S. (1993). Why behavior analysis is a natural science. In Readings for strategies and tactics of behavioral research (2nd ed., pp. xii, 210-xii, 210). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Johnston, J. M., Pennypacker, H. S., & Green, G. (2020). Strategies and tactics of behavioral research and practice. (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Karst, J. S., & Van Hecke, A. V. (2012). Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: a review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev, 15(3), 247-277. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. V., Baranek, G. T., & Fox, L. (2016). Longitudinal Predictors of Outcomes for Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review. OTJR (Thorofare N J), 36(2), 55-64. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. The Lancet, 383(9920), 896-910. [CrossRef]

- Laros, J. A., Reis, R. F., & Tellegen, P. J. (2010). Indicações da validade convergente do teste Não-Verbal de Inteligência Son-R 2½-7[A]. Avaliação Psicológica, 9, 43-52. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712010000100006&nrm=iso.

- Law, G. C., Neihart, M., & Dutt, A. (2018). The use of behavior modeling training in a mobile app parent training program to improve functional communication of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(4), 424-439. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D., & Meadan, H. (2021). Parent-Mediated Interventions for Children with ASD in Low-Resource Settings: a Scoping Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(3), 285-298. [CrossRef]

- Linstead, E., Dixon, D. R., Hong, E., Burns, C. O., French, R., Novack, M. N., & Granpeesheh, D. (2017). An evaluation of the effects of intensity and duration on outcomes across treatment domains for children with autism spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry, 7(9), e1234. [CrossRef]

- Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G., & Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet, 392(10146), 508-520. [CrossRef]

- Lord, C., & Schopler, E. (1985). Differences in sex ratios in autism as a function of measured intelligence. J Autism Dev Disord, 15(2), 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Magan-Maganto, M., Bejarano-Martin, A., Fernandez-Alvarez, C., Narzisi, A., Garcia-Primo, P., Kawa, R., Posada, M., & Canal-Bedia, R. (2017). Early Detection and Intervention of ASD: A European Overview. Brain Sci, 7(12). [CrossRef]

- Mattila, M. L., Kielinen, M., Linna, S. L., Jussila, K., Ebeling, H., Bloigu, R., Joseph, R. M., & Moilanen, I. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders according to DSM-IV-TR and comparison with DSM-5 draft criteria: an epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 50(6), 583-592 e511. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, E., Vernon, T., & Baktha, A. (2020). Brief Report: A Pilot Online Pivotal Response Treatment Training Program for Parents of Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 50(9), 3424-3431. [CrossRef]

- Monlux, K., Pelaez, M., & Holth, P. (2019). Joint attention and social referencing in children with autism: a behavior-analytic approach. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 20(2), 186-203. [CrossRef]

- Mundy, P. (2018). A review of joint attention and social-cognitive brain systems in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Eur J Neurosci, 47(6), 497-514. [CrossRef]

- Mundy, P., & Burnette, C. (2005). Joint attention and neurodevelopmental models of autism. In F. R. Volkmar, R. Paul, A. J. Klin, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (3rd ed., pp. 650–681). Wiley.

- Narzisi, A., Costanza, C., Umberto, B., & Filippo, M. (2014). Non-pharmacological treatments in autism spectrum disorders: an overview on early interventions for pre-schoolers. Curr Clin Pharmacol, 9(1), 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Nevill, R. E., Lecavalier, L., & Stratis, E. A. (2018). Meta-analysis of parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(2), 84-98. [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, K. L., Armitage, S., Featherstone, J., McQuillin, L., Longley, S., & Pollard, N. (2019). Group-Based Parent Training Interventions for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: a Literature Review [journal article]. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(1), 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., & Lee, H. C. (2017). Parent-Mediated Intervention Training Delivered Remotely for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Living Outside of Urban Areas: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 19(8), e198. [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M., & Monlux, K. (2018). Development of Communication in Infants: Implications for Stimulus Relations Research. Perspect Behav Sci, 41(1), 175-188. [CrossRef]

- Peters-Scheffer, N., Didden, R., Korzilius, H., & Sturmey, P. (2011). A meta-analytic study on the effectiveness of comprehensive ABA-based early intervention programs for children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 60-69. [CrossRef]

- Piven, J., Elison, J. T., & Zylka, M. J. (2017). Toward a conceptual framework for early brain and behavior development in autism. Mol Psychiatry, 22(10), 1385-1394. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A., Divan, G., Hamdani, S. U., Vajaratkar, V., Taylor, C., Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., Minhas, A., Cardozo, P., Emsley, R., Patel, V., & Green, J. (2016). Effectiveness of the parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder in south Asia in India and Pakistan (PASS): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(2), 128-136. [CrossRef]

- Reichow, B., Servili, C., Yasamy, M. T., Barbui, C., & Saxena, S. (2013). Non-specialist psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents with intellectual disability or lower-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. PLoS Med, 10(12), e1001572; discussion e1001572. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., Guo, M., & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a brief Early Start Denver model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 51(10), 1052-1065. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Vismara, L., Munson, J., Zierhut, C., Greenson, J., Dawson, G., Rocha, M., Sugar, C., Senturk, D., Whelan, F., & Talbott, M. (2019). Enhancing Low-Intensity Coaching in Parent Implemented Early Start Denver Model Intervention for Early Autism: A Randomized Comparison Treatment Trial. J Autism Dev Disord, 49(2), 632-646. [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Ruiz, J., & Baer, D. M. (1997). Behavioral cusps: a developmental and pragmatic concept for behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal, 30(3), 533-544. [CrossRef]

- Scahill, L., Bearss, K., Lecavalier, L., Smith, T., Swiezy, N., Aman, M. G., Sukhodolsky, D. G., McCracken, C., Minshawi, N., Turner, K., Levato, L., Saulnier, C., Dziura, J., & Johnson, C. (2016). Effect of Parent Training on Adaptive Behavior in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Disruptive Behavior: Results of a Randomized Trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 55(7), 602-609 e603. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T. R., Schmidt, C. T., & Stichter, J. P. (2011). A Review of Parent Education Programs for Parents of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 96-104. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. (2013). What is evidence-based behavior analysis? Behav Anal, 36(1), 7-33. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales: Interview edition, survey form manual. American Guidance Service.

- Stahmer, A. C., Dababnah, S., & Rieth, S. R. (2019). Considerations in implementing evidence-based early autism spectrum disorder interventions in community settings. Pediatr Med, 2. [CrossRef]

- Steinbrenner, J. R., Hume, K., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2020). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism. . The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team. https://ncaep.fpg.unc.edu/sites/ncaep.fpg.unc.edu/files/imce/documents/EBP%20Report%202020.pdf.

- Tellegen, C. L., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial evaluating a brief parenting program with children with autism spectrum disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol, 82(6), 1193-1200. [CrossRef]

- Tiura, M., Kim, J., Detmers, D., & Baldi, H. (2017). Predictors of longitudinal ABA treatment outcomes for children with autism: A growth curve analysis. Res Dev Disabil, 70, 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Virues-Ortega, J. (2010). Applied behavior analytic intervention for autism in early childhood: meta-analysis, meta-regression and dose-response meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev, 30(4), 387-399. [CrossRef]

- Vismara, L. A., McCormick, C., Young, G. S., Nadhan, A., & Monlux, K. (2013). Preliminary findings of a telehealth approach to parent training in autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 43(12), 2953-2969. [CrossRef]

- Volkmar, F., Siegel, M., Woodbury-Smith, M., King, B., McCracken, J., State, M., American Academy of, C., & Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality, I. (2014). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 53(2), 237-257. [CrossRef]

- Volkmar, F. R., Szatmari, P., & Sparrow, S. S. (1993). Sex differences in pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 23(4), 579-591. [CrossRef]

- Wainer, A. L., & Ingersoll, B. R. (2015). Increasing Access to an ASD Imitation Intervention Via a Telehealth Parent Training Program. J Autism Dev Disord, 45(12), 3877-3890. [CrossRef]

- Warren, Z., Veenstra-VanderWeele, J., Stone, W., Bruzek, J. L., Nahmias, A. S., Foss-Feig, J. H., Jerome, R. N., Krishnaswami, S., Sathe, N. A., Glasser, A. M., Surawicz, T., & McPheeters, M. L. (2011). Therapies for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. In Comparative Effectiveness Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

- Wetherby, A. M., Woods, J., Guthrie, W., Delehanty, A., Brown, J. A., Morgan, L., Holland, R. D., Schatschneider, C., & Lord, C. (2018). Changing Developmental Trajectories of Toddlers With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Strategies for Bridging Research to Community Practice. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 61(11), 2615-2628. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., Brock, M. E., Plavnick, J. B., Fleury, V. P., & Schultz, T. R. (2015). Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Review. J Autism Dev Disord, 45(7), 1951-1966. [CrossRef]

- Zwaigenbaum, L., Bryson, S. E., Szatmari, P., Brian, J., Smith, I. M., Roberts, W., Vaillancourt, T., & Roncadin, C. (2012). Sex differences in children with autism spectrum disorder identified within a high-risk infant cohort. J Autism Dev Disord, 42(12), 2585-2596. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).