Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Sample

2.2.1. HPs

2.2.2. Parents

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Materials and Measures

2.4.1. Social-structural aspects

2.4.2. Psychological dispositions

2.4.3. Vaccine-specific factors

2.4.4. Trust-related measures

2.4.5. Vaccination intention

2.5. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

3.2. Do psychological dispositions moderate the relationships between negative attitudes toward immunization and vaccination intention?

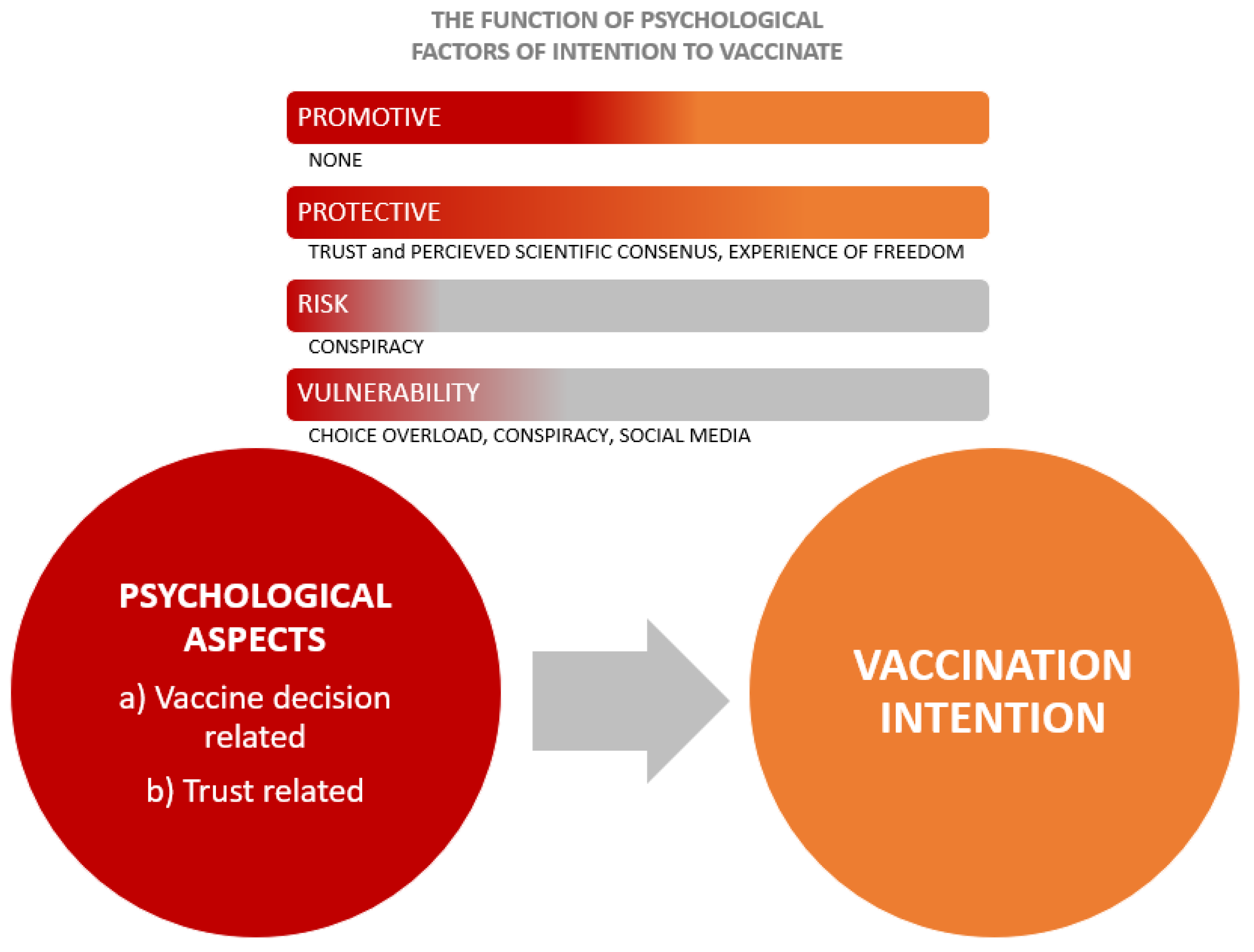

- passive risk-taking is a vulnerability factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in a sub-sample of health professionals;

- epistemic credulity is a vulnerability factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in the parents sub-sample;

- open-minded thinking is a protective factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in the lay people sub-sample.

3.3. Do vaccine-specific factors moderate the relationships between negative attitudes toward immunization and vaccination intention?

- conspiracy beliefs are risk factors in all three sub-samples;

- experience of freedom is a promotive factor in the sub-sample of health professionals;

- perceived consensus is a promotive factor in a parents’ sub-sample.

- conspiracy beliefs and choice overload are vulnerability factors in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in all three sub-samples;

- perceived consensus and experience of freedom are a protective factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in all three sub-samples;

3.4. Do trust-related measures moderate the relationships between negative attitudes toward immunization and vaccination intention??

- trust in corporations and trust in health-care system are promotive factors in the parents’ sub-sample;

- trust in social networks is a risk factor in the sub-sample of lay people.

- trust in corporations, government, and health-care system are a protective factors in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in all three sub-samples;

- trust in scientists is a protective factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in sub-samples of HPs and lay people;

- trust in mainstream and independent media is a protective factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in sub-samples of health providers;

- trust in social networks is a vulnerability factor in the relationship between negative attitudes and vaccination intention in all three sub-samples.

| Moderator (always TA) | Health providers | Parents | Lay people | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E | Β | B | S.E | Β | B | S.E | β | |||

| TA: corporations | R = .608**, ΔR2 = .062** | R = .799**, ΔR2 = .024** | R = .846**, ΔR2 = .021** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.482 | .101 | -.339** | -1.181 | .090 | -.667** | -1.106 | .068 | -.702** | ||

| TA: corporations | .159 | .082 | .111 | .283 | .080 | .149** | .076 | .055 | .052 | ||

| Interaction | .468 | .101 | .317** | .393 | .095 | .133** | .286 | .065 | .193** | ||

| TA: government | R = .619**, ΔR2 = .078** | R = .791**, ΔR2 = .015** | R = .852**, ΔR2 = .029** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.451 | .103 | -.317** | -1.204 | .100 | -.649** | -.892 | .077 | -.616** | ||

| TA: government | .110 | .083 | .077 | .204 | .083 | .110 | .133 | .055 | .092 | ||

| Interaction | .438 | .084 | .351** | .321 | .099 | .164** | .323 | .062 | .251** | ||

| TA: health-care system | R = .665**, ΔR2 = .117** | R = .813**, ΔR2 = .037** | R = .859**, ΔR2 = .038** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.261 | .104 | -.184* | -.882 | .114 | -.475** | -.792 | .082 | -.547** | ||

| TA: health-care system | .090 | .089 | .064 | .319 | .090 | .172** | .106 | .064 | .073 | ||

| Interaction | .390 | .058 | .486** | .377 | .070 | .273** | .271 | .044 | .306** | ||

| TA: scientists | R = .625**, ΔR2 = .070** | R = .786**, ΔR2 = .004 | R = .839**, ΔR2 = .007* | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.520 | .095 | -.366** | -1.281 | .101 | -.690** | -1.112 | .067 | -.768** | ||

| TA: scientists | -.079 | .107 | -.055 | .101 | .099 | .054 | -.038 | .078 | -.027 | ||

| Interaction | .316 | .064 | .382** | .108 | .064 | .088 | .118 | .047 | .132* | ||

| TA: mainstream media | R = .576**, ΔR2 = .024** | R = .781**, ΔR2 = .000 | R = .838**, ΔR2 = .004 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.707 | .084 | -.497** | -1.428 | .083 | -.769** | -1.160 | .064 | -.801** | ||

| TA: mainstream media | .084 | .080 | .059 | .058 | .081 | .031 | -.050 | .053 | -.035 | ||

| Interaction | .246 | .088 | .165** | .031 | .103 | .014 | .118 | .064 | .078 | ||

| TA: independent media | R = .569**, ΔR2 = .017* | R = .780**, ΔR2 = .000 | R = .836**, ΔR2 = .000 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.783 | .080 | -.551** | -1.453 | .074 | -.783** | -1.235 | .055 | -.853** | ||

| TA: independent media | .060 | .080 | .042 | -.016 | .073 | -.009 | -.085 | .052 | -.059 | ||

| Interaction | .184 | .080 | .129* | -.011 | .072 | -.006 | -.004 | .043 | -.003 | ||

| TA: social networks | R = .586**, ΔR2 = .027** | R = .793**, ΔR2 = .011** | R = .848**, ΔR2 = .013** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.683 | .084 | -.481** | -1.357 | .073 | -.741** | -1.185 | .048 | -.819** | ||

| TA: social networks | -.139 | .079 | -.098 | -.153 | .071 | -.082 | -.124 | .049 | -.086* | ||

| Interaction | -.216 | .073 | -.274** | -.167 | .059 | -.110** | -.144 | .041 | -.116** | ||

4. Discussion

4.1. General findings

4.2. Similarities between parents, healthcare providers, and laypeople

4.3. Differences between parents, healthcare providers, and laypeople

4.4. Moderating and direct effects of trust in different sources of information across three samples

4.5. Limitations and future directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Allington, D., Duffy, B., Wessely, S., Dhavan, N., & Rubin, J. (2021). Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency – CORRIGENDUM. Psychological Medicine, 51(10), 1770–1770. [CrossRef]

- Arnesen, S., Bærøe, K., Cappelen, C., & Carlsen, B. (2018). Could information about herd immunity help us achieve herd immunity? Evidence from a population representative survey experiment. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Bangerter, A., Krings, F., Mouton, A., Gilles, I., Green, E. G. T., & Clémence, A. (2012). Longitudinal investigation of public trust in institutions relative to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Switzerland. PloS One, 7(11), e49806. [CrossRef]

- Baron, J. (1993). Why Teach Thinking?-An Essay. Applied Psychology, 42(3), 191–214. [CrossRef]

- Baron, J., Scott, S., Fincher, K., & Emlen Metz, S. (2015). Why does the Cognitive Reflection Test (sometimes) predict utilitarian moral judgment (and other things)? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(3), 265–284. [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, V., Bauer, M., Cahlíková, J., & Chytilová, J. (2022). C ommunicating doctors’ consensus persistently increases COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature, 606(7914), Article 7914. [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. [CrossRef]

- Bedford, H. (2014). Pro-vaccine messages may be counterproductive among vaccine-hesitant parents. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 19(6), 219–219. [CrossRef]

- Bertin, P., Nera, K., & Delouvée, S. (2020). Conspiracy Beliefs, Rejection of Vaccination, and Support for hydroxychloroquine: A Conceptual Replication-Extension in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128.

- Camargo, K., & Grant, R. (2015). Public Health, Science, and Policy Debate: Being Right Is Not Enough. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 232–235. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C., Tanzer, M., Saunders, R., Booker, T., Allison, E., Li, E., O’Dowda, C., Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2021). Development and validation of a self-report measure of epistemic trust. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0250264. [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S., Pizam, A., & Wang, Y. (2021). An Integrated Behavioral Model for Medical Tourism: An American Perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 761–778. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. T., & Orenstein, W. A. (1996). Epidemiologic methods in immunization programs. Epidemiologic Reviews, 18(2), 99–117. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C., & Tse, J. W. (2008). Institutional Trust As a Determinant of Anxiety During the SARS Crisis in Hong Kong. Social Work in Public Health, 23(5), 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Corace, K. M., Srigley, J. A., Hargadon, D. P., Yu, D., MacDonald, T. K., Fabrigar, L. R., & Garber, G. E. (2016). Using behavior change frameworks to improve healthcare worker influenza vaccination rates: A systematic review. Vaccine, 34(28), 3235–3242. [CrossRef]

- Damnjanović, K., Graeber, J., Ilić, S., Lam, W. Y., Lep, Ž., Morales, S., Pulkkinen, T., & Vingerhoets, L. (2018a). Parental Decision-Making on Childhood Vaccination. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 326661. [CrossRef]

- Damnjanović, K., Graeber, J., Ilić, S., Lam, W. Y., Lep, Ž., Morales, S., Pulkkinen, T., & Vingerhoets, L. (2018b). Parental Decision-Making on Childhood Vaccination. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00735.

- Damnjanović, K., Ilić, S., Pavlović, I., & Novković, V. (2019). Refinement of Outcome Bias Measurement in the Parental Decision-Making Context. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- De Visser, R., Waites, L., Parikh, C., & Lawrie, A. (2011). The importance of social norms for uptake of catch-up human papillomavirus vaccination in young women. Sexual Health, 8(3), 330. [CrossRef]

- Enea, V., Eisenbeck, N., Carreno, D. F., Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Agostini, M., Bélanger, J. J., Gützkow, B., Kreienkamp, J., Abakoumkin, G., Abdul Khaiyom, J. H., Ahmedi, V., Akkas, H., Almenara, C. A., Atta, M., Bagci, S. C., Basel, S., Berisha Kida, E., Bernardo, A. B. I., … Leander, N. P. (2023). Intentions to be Vaccinated Against COVID-19: The Role of Prosociality and Conspiracy Beliefs across 20 Countries. Health Communication, 38(8), 1530–1539. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Funk, S., Gilad, E., Watkins, C., & Jansen, V. A. A. (2009). The spread of awareness and its impact on epidemic outbreaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(16), 6872–6877. [CrossRef]

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A., & Badarna Keywan, H. (2022). Physicians’ Perspective on Vaccine-Hesitancy at the Beginning of Israel’s COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign and Public’s Perceptions of Physicians’ Knowledge When Recommending the Vaccine to Their Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 855468. [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (n.d.). Theory, Research, and Practice.

- Goldenberg, M. J. (2014). How can Feminist Theories of Evidence Assist Clinical Reasoning and Decision-making? Social Epistemology. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02691728.2013.794871.

- Goldenberg, M. J. (2021). Vaccine Hesitancy: Public Trust, Expertise, and the War on Science. University of Pittsburgh Press. [CrossRef]

- Gowda, C., & Dempsey, A. F. (2013). The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1755–1762. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q., Zheng, B., Cristea, M., Agostini, M., Bélanger, J. J., Gützkow, B., Kreienkamp, J., Collaboration, P., & Leander, N. P. (2023). Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Hobson-West, P. (2007). ‘Trusting blindly can be the biggest risk of all’: Organised resistance to childhood vaccination in the UK. Sociology of Health & Illness, 29(2), 198–215. [CrossRef]

- Horne, Z., Powell, D., Hummel, J. E., & Holyoak, K. J. (2015). Countering antivaccination attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(33), 10321–10324. [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., & Fielding, K. S. (2018). The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychology, 37(4), 307–315. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H. P., & Senger, A. R. (2021). A little shot of humility: Intellectual humility predicts vaccination attitudes and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(4), 449–460. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006. [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2014). The Effects of Anti-Vaccine Conspiracy Theories on Vaccination Intentions. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e89177. [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D. M. (2013). Social science. A risky science communication environment for vaccines. Science (New York, N.Y.), 342(6154), 53–54. [CrossRef]

- Keinan, R., & Bereby-Meyer, Y. (2012). “Leaving it to chance”—Passive risk taking in everyday life. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(6), 705–715. [CrossRef]

- Khodyakov, D. (2007). Trust as a Process: A Three-Dimensional Approach. Sociology, 41(1), 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Kiviniemi, M. T., Ellis, E. M., Hall, M. G., Moss, J. L., Lillie, S. E., Brewer, N. T., & Klein, W. M. P. (2018). Mediation, moderation, and context: Understanding complex relations among cognition, affect, and health behaviour. Psychology & Health, 33(1), 98–116. [CrossRef]

- Kutasi, K., Koltai, J., Szabó-Morvai, Á., Röst, G., Karsai, M., Biró, P., & Lengyel, B. (2022). Understanding hesitancy with revealed preferences across COVID-19 vaccine types. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 13293. [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. (2020). COVID-19: Fighting panic with information. The Lancet, 395(10224), 537. [CrossRef]

- Larson, H., Leask, J., Aggett, S., Sevdalis, N., & Thomson, A. (2013). A Multidisciplinary Research Agenda for Understanding Vaccine-Related Decisions. Vaccines, 1(3), 293–304. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S., Hiemisch, A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2015). The experience of freedom in decisions—Questioning philosophical beliefs in favor of psychological determinants. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 33, 30–46. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J. V., Wyka, K., White, T. M., Picchio, C. A., Rabin, K., Ratzan, S. C., Parsons Leigh, J., Hu, J., & El-Mohandes, A. (2022). Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nature Communications, 13(1), 3801. [CrossRef]

- Lazić, A., & Zezelj, I. (2021). A systematic review of narrative interventions: Lessons for countering anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and misinformation. PsyArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Lep, Ž., Ilić, S., Teovanović, P., Hacin Beyazoglu, K., & Damnjanović, K. (2021). One Hundred and Sixty-One Days in the Life of the Homopandemicus in Serbia: The Contribution of Information Credibility and Alertness in Predicting Engagement in Protective Behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631791.

- Lewandowsky, S., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(2), 348–384. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. A., & Lagoe, C. (2013). Effects of News Media and Interpersonal Interactions on H1N1 Risk Perception and Vaccination Intent. Communication Research Reports, 30(2), 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Managing epidemics: Key facts about major deadly diseases. (n.d.). Retrieved 17 September 2023, from https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/managing-epidemics-key-facts-about-major-deadly-diseases.

- McClure, C. C., Cataldi, J. R., & O’Leary, S. T. (2017). Vaccine Hesitancy: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Clinical Therapeutics, 39(8), 1550–1562. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Board on Children, Y., Fischhoff, B., Nightingale, E. O., & Iannotta, J. G. (2001). Vulnerability, Risk, and Protection. In Adolescent Risk and Vulnerability: Concepts and Measurement. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223737/.

- Newton, C., Feeney, J., & Pennycook, G. (2023). On the Disposition to Think Analytically: Four Distinct Intuitive-Analytic Thinking Styles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672231154886. [CrossRef]

- Nikic, P., Stankovic, B., Santric, V., Vukovic, I., Babic, U., Radovanovic, M., Bojanic, N., Acimovic, M., Kovacevic, L., & Prijovic, N. (2023). Role of Healthcare Professionals and Sociodemographic Characteristics in COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance among Uro-Oncology Patients: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Vaccines, 11(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Ninković, M., Damnjanović, K., & Ilić, S. (2022). Structure and Misuse of Women’s Trust in the Healthcare System in Serbia. PsyArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Opel, D. J., Heritage, J., Taylor, J. A., Mangione-Smith, R., Salas, H. S., DeVere, V., Zhou, C., & Robinson, J. D. (2013). The Architecture of Provider-Parent Vaccine Discussions at Health Supervision Visits. Pediatrics, 132(6), 1037–1046. [CrossRef]

- Oraby, T., Thampi, V., & Bauch, C. T. (2014). The influence of social norms on the dynamics of vaccinating behaviour for paediatric infectious diseases. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 281(1780), 20133172. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S. A., & Goodman, R. A. (2020). Field epidemiology and COVID-19: Always more lessons to be learned. International Journal of Epidemiology, dyaa221. [CrossRef]

- Reyna, V. F. (2012). Risk perception and communication in vaccination decisions: A fuzzy-trace theory approach. Vaccine, 30(25), 3790–3797. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 354–386. [CrossRef]

- Rosental, H., & Shmueli, L. (2021). Integrating Health Behavior Theories to Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: Differences between Medical Students and Nursing Students. Vaccines, 9(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K., Stock, F., Haslam, S. A., Capraro, V., Boggio, P., Ellemers, N., Cichocka, A., Douglas, K., Rand, D. G., Cikara, M., Finkel, E., Linden, S. V. D., Druckman, J., Wohl, M. J. A., Petty, R., Tucker, J. A., Peters, E., Shariff, A., Gelfand, M., … Willer, R. (2022). Evaluating expectations from social and behavioral science about COVID-19 and lessons for the next pandemic [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N., McIntosh, R. C., & Antoni, M. H. (2019). Psychosocial risk and management of physical diseases. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42(1), 16–33. [CrossRef]

- Schumpe, B. M., Van Lissa, C. J., Bélanger, J. J., Ruggeri, K., Mierau, J., Nisa, C. F., Molinario, E., Gelfand, M. J., Stroebe, W., Agostini, M., Gützkow, B., Jeronimus, B. F., Kreienkamp, J., Kutlaca, M., Lemay, E. P., Reitsema, A. M., vanDellen, M. R., Abakoumkin, G., Abdul Khaiyom, J. H., … Leander, N. P. (2022). Predictors of adherence to public health behaviors for fighting COVID-19 derived from longitudinal data. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Seddig, D., Maskileyson, D., Davidov, E., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2022). Correlates of COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Attitudes, institutional trust, fear, conspiracy beliefs, and vaccine skepticism. Social Science & Medicine, 302, 114981. [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, S., Holur, P., Wang, T., Tangherlini, T. R., & Roychowdhury, V. (2020). Conspiracy in the time of corona: Automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. Journal of Computational Social Science, 3(2), 279–317. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, G. K., Holding, A., Perez, S., Amsel, R., & Rosberger, Z. (2016). Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Research (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. (2021). Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Stankovic, B. (2017). Women’s Experiences of Childbirth in Serbian Public Healthcare Institutions: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24(6), 803–814. [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K. E., & Toplak, M. E. (2023). Actively Open-Minded Thinking and Its Measurement. Journal of Intelligence, 11(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, A., Hoffmann, J., Mause, L., Neufeind, J., Ohnhäuser, T., & Scholten, N. (2023). What impact does the attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination have on physicians as vaccine providers? A cross sectional study from the German outpatient sector. Vaccine, 41(1), 263–273. [CrossRef]

- Teovanović, P., Lukić, P., Zupan, Z., Lazić, A., Ninković, M., & Žeželj, I. (2021). Irrational beliefs differentially predict adherence to guidelines and pseudoscientific practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(2), 486–496. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K., Nilsson, E., Festin, K., Henriksson, P., Lowén, M., Löf, M., & Kristenson, M. (2020). Associations of Psychosocial Factors with Multiple Health Behaviors: A Population-Based Study of Middle-Aged Men and Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1239. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A. G. H. (2007). The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: A taxonomy. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64(6), 1297–1310. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S. (2011). Charitable Intent: A Moral or Social Construct? A Revised Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Current Psychology, 30(4), 355–374. [CrossRef]

- Wicaksana, B., Yunihastuti, E., Shatri, H., Pelupessy, D. C., Koesnoe, S., Djauzi, S., Mahdi, H. I. S., Waluyo, D. A., Djoerban, Z., & Siddiq, T. H. (2023). Predicting Intention to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination in People Living with HIV using an Integrated Behavior Model. Vaccines, 11(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Zingg, A., & Siegrist, M. (2012). Measuring people’s knowledge about vaccination: Developing a one-dimensional scale. Vaccine, 30(25), 3771–3777. [CrossRef]

| Moderator: | Health providers | Parents | Lay people | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E | β | B | S.E | β | B | S.E | β | |||

| Passive risk-taking | R = .565**, ΔR2 = .013* | R = .782**, ΔR2 = .002 | R = .835**, ΔR2 = .000 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.755 | .082 | -.531** | -1.439 | .073 | -.775** | -1.229 | .055 | -.849** | ||

| Passive risk taking | -.028 | .081 | -.020 | .014 | .073 | .008 | .054 | .052 | .037 | ||

| Interaction | -.137 | .068 | -.115* | -.073 | .066 | -.043 | .016 | .054 | .011 | ||

| AOT | R = .556**, ΔR2 = .004 | R = .781**, ΔR2 = .000 | R = .850**, ΔR2 = .022** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.776 | .082 | -.546** | -1.439 | .073 | -.775** | -1.002 | .063 | -.692** | ||

| AOT | .005 | .082 | -.004 | .047 | .073 | .025 | .084 | .055 | .058 | ||

| Interaction | -.090 | .082 | -.063 | .038 | .067 | .022 | .189 | .042 | .187** | ||

| Epistemic trust | R = .558**, ΔR2 = .003 | R = .780**, ΔR2 = .000 | R = .834**, ΔR2 = .000 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.798 | .082 | -.561** | -1.448 | .074 | -.780** | -1.201 | .051 | -.829** | ||

| Epistemic trust | -.079 | .081 | -.056 | -.008 | .074 | -.004 | .018 | .050 | .050 | ||

| Interaction | .079 | .084 | .054 | .008 | .063 | .005 | .021 | .045 | .045 | ||

| Epistemic mistrust | R = .564**, ΔR2 = .002 | R = .781**, ΔR2 = .000 | R = .834**, ΔR2 = .000 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.796 | .080 | -.560** | -1.449 | .072 | -.781** | -1.211 | .050 | -.836** | ||

| Epistemic mistrust | .146 | .080 | .103 | .067 | .073 | .036 | -.002 | .050 | -.002 | ||

| Interaction | -.063 | .086 | -.042 | .022 | .087 | .010 | .019 | .043 | .043 | ||

| Epistemic credulity | R = .557**, ΔR2 = .001 | R = .785**, ΔR2 = .006* | R = .834**, ΔR2 = .001 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.773 | .083 | -.543** | -1.461 | .072 | -.787** | -1.207 | .051 | -.831** | ||

| Epistemic credulity | .078 | .081 | .055 | -.039 | .072 | -.021 | .008 | .052 | .006 | ||

| Interaction | .052 | .078 | .039 | -.161 | .078 | -.079* | -.041 | .046 | -.031 | ||

| Moderator: | Health providers | Parents | Lay people | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E | β | B | S.E | β | B | S.E | β | |||

| Experience of freedom | R = .608**, ΔR2 = .036** | R = .788**, ΔR2 = .008* | R = .847**, ΔR2 = .022** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.564 | .091 | -.397** | -1.323 | .086 | -.713** | -1.072 | .058 | -.740** | ||

| Experience of freedom | .238 | .081 | .167** | .085 | .084 | .046 | .055 | .050 | .038 | ||

| Interaction | .236 | .068 | .216** | .148 | .064 | .102* | .242 | .054 | .170** | ||

| Choice overload | R = .598**, ΔR2 = .048** | R = .792**, ΔR2 = .008* | R = .838**, ΔR2 = .005* | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.548 | .096 | -.385** | -1.231 | .093 | -.663** | -1.141 | .057 | -.788** | ||

| Choice overload | -.126 | .080 | -.089 | -.163 | .069 | -.088 | -.075 | .052 | -.052 | ||

| Interaction | -.322 | .081 | -.264** | -.166 | .069 | -.116* | -.117 | .058 | -.077* | ||

| Perceived consensus | R = .678**, ΔR2 = .128** | R = .794**, ΔR2 = .017** | R = .848**, ΔR2 = .023** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.340 | .092 | -.239** | -1.137 | .107 | -.612** | -.913 | .085 | -.621** | ||

| Perceived consensus | .110 | .083 | .077 | .185 | .085 | .100* | -.030 | .066 | -.021 | ||

| Interaction | .388 | .054 | .463** | .243 | .072 | .171** | .207 | .045 | .242** | ||

| Subjective norms | R = .560**, ΔR2 = .004 | R = .785**, ΔR2 = .005 | R = .836**, ΔR2 = .003 | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.783 | .081 | -.550** | -1.381 | .078 | -.744** | -1.424 | .146 | -.983** | ||

| Subjective norms | .105 | .081 | .074 | .068 | .077 | .037 | .024 | .051 | .017 | ||

| Interaction | -.087 | .082 | -.061 | .125 | .065 | .078 | .047 | .029 | .163 | ||

| Conspiracy beliefs | R = .656**, ΔR2 = .094** | R = .825**, ΔR2 = .039** | R = .874**, ΔR2 = .040** | ||||||||

| Negative attitudes | -.182 | .119 | -.128* | -.582 | .131 | -.314** | -.561 | .091 | -.387** | ||

| Conspiracy beliefs | -.170 | .107 | -.119* | -.547 | .106 | -.295** | -.318 | .085 | -.220** | ||

| Interaction | -.307 | .051 | -.466** | -.368 | .065 | -.306** | -.236 | .036 | -.332** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).