Preprint

Article

Printability Properties of Protein Gel Obtained from Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) in the 3D Food Printing of Deep-Space Food

Altmetrics

Downloads

164

Views

107

Comments

0

Submitted:

03 October 2023

Posted:

04 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Increasing the availability of alternative protein from insects is important to solving food shortages. Not only are insects a rich source of protein, the use of insect ingredi-ents can reduce food waste. Insects are thus a potentially valuable ingredient for food industries and even food eaten on deep-space missions. The three-dimensional produc-tion of food on space missions has gained attention owing to its potential to reduce au-tonomous food production and produce sustainable food for long-duration space mis-sions. This study investigated the printability and rheological properties of a high-protein food system derived from mealworms and guar gum used as a stabilizer to im-prove printability. Stability and rheological properties were analyzed for various print-ing parameters. The results indicate that as the guar gum concentration was increased from 0 to 1.75%, the yield stress of the mealworm paste increased from 39 to 1096 Pa. Increasing the guar gum concentration thus resulted in a mealworm paste that was more viscous, exhibited shear thinning behavior, could support itself and was thus more stable. In summary, introducing guar gum resulted in a mealworm paste with rheological properties more suitable for printing in terms of printability and stability.

Keywords:

Subject: Engineering - Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering

1. Introduction

There is a demand for sustainable protein sources owing to concerns about a lack of food resources and the environmental effects of agriculture. Many researchers have thus investigated alternative protein sources, one of which is insect protein. Insects have long been consumed in various cultures worldwide, but their potential as a sustainable protein source is only now being recognized on a global scale [1]. Insects are highly nutritious, require minimal resources for production, and emit lower amounts of greenhouse gases than traditional livestock [2]. Insects, with their rich protein content and high feed conversion efficiency, are thus a viable solution for addressing the increasing demand for protein in a sustainable manner.

The mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) is an insect that is bred and eaten in its larval stage. Mealworms have the potential to be an insect-based protein product owing to their rich protein content and nutrition [3]. Karin et al. [4] reported that mealworms have a nutty flavor acceptable to panelists. Many studies have focused on substituting ingredients in food with mealworm. Anna et al. [5], for example, studied mealworm flour substitution in protein-rich crackers and found that the crackers with substituted mealworm flour had higher protein content than the original crackers. Mealworms thus have potential uses in protein-rich products. In addition, mealworm larvae containing a high level of protein readily develop on the detritus of low-nutrient plants [6]. Mealworms are thus a potential sustainable food source that can be produced on a large scale. In a specific application, mealworms are a potential sustainable food source in the human exploration of distant planets and other long-duration human space missions [7] because their rapid growth and rich nutrition enable efficient food production [8]. Jones [9] suggested that the daily consumption of roasted mealworms on a long-duration space mission could reach 14,720 g or 161,920 mealworms, considering that 11 mealworms of medium size have a combined mass of 100 g. The potential use of mealworms as a source of protein in deep-space exploration could therefore alleviate logistical challenges and provide astronauts with a sustainable and locally producible meat source [10].

Moreover, 3D food printing has the potential to address the challenges posed by the long duration and limited resources of deep-space missions [11]. This technology could enable astronauts to produce customized, nutritious meals on demand using readily available ingredients and to reduce food waste. The adoption of 3D food printing on space missions could reduce the reliance on pre-packaged meals and provide astronauts with diets that are more sustainable and diverse. In addition, 3D food printing enables the creation of intricately designed and personalized meals, catering to specific dietary needs and preferences. Furthermore, 3D food printing can enhance the nutritional content of food through the incorporation of fortified ingredients or alternative protein sources [12]. The technology has the potential to reduce food waste through the efficient use of ingredients and minimization of excess production [13].

The printability of a material is the most important factor affecting 3D food printing [14] and is determined by the rheological properties of the printed material [15]. The rheological properties that affect material behavior are the yield stress, viscosity, shear-thinning behavior, storage modulus, and shear recovery [16]. Hydrocolloids, when mixed with water, form a gel or colloidal structure and improve material printability [17].

Guar gum is a hydrocolloid that originates from the seeds of the Cyamopsis tetragonoloba, which belongs to the Leguminosae family [18]. Guar gum has remarkable properties, including its abilities to form stable gels, enable excellent water binding, enhance viscosity, and improve the shear thinning properties of fluids [19]. These characteristics make guar gum an important ingredient in 3D food printing. In addition, guar gum prevents the structural collapse of the printed food in the deposition stage of printing [20]. Dick et al. [21] reported that the addition of guar gum made from ground pork provided a printed product with mechanical strength and a self-support ability.

The present paper investigates the rheological properties of dried mealworms improved with the addition of guar gum and the effects of 3D printing parameters on the printability of dried mealworm paste (MP) in terms of the yield stress, shear thinning property, and stability after printing. The results provide guidelines for food production from insect protein using 3D food printing technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and preparation

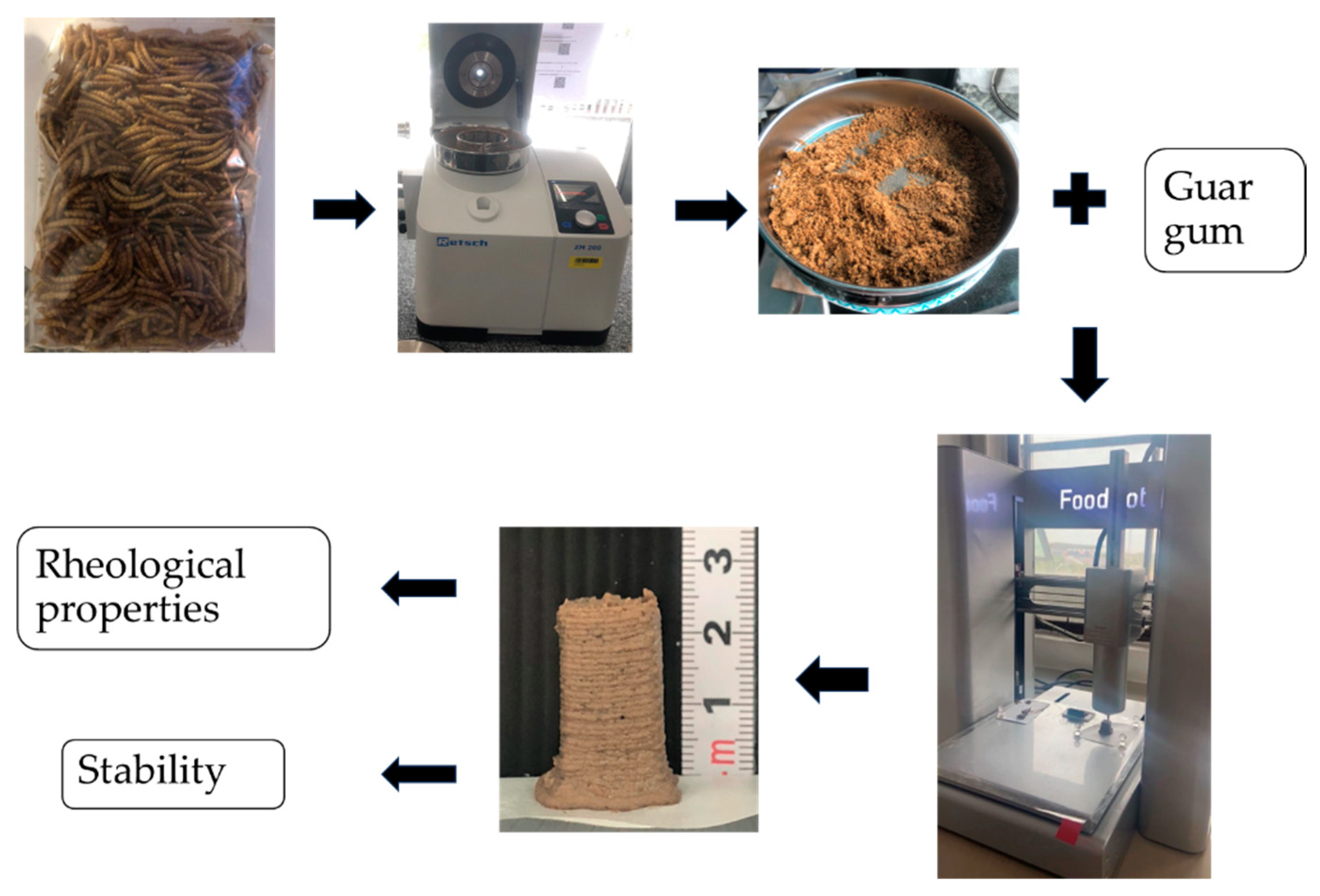

Dried mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) was finely ground into powder using an Ultra Centrifugal Mill (Retsch Ultra Centrifugal Mill ZM 200, Haan, Germany) with a stainless-steel ring sieve having a pore size of 1.0 mm as shown in Figure 1. The original dried mealworm is shown in Figure 2a. The ground dried mealworm powder was sealed in a zip-lock plastic bag and kept at 4 °C.

2.2. MP preparation

The dried powdered mealworm was mixed with hot water at a ratio of 1:1 w/w and then blended in a blender (PHILIPS HR2221/00, Eindhoven, Netherlands). A hand homogenizer was used for subsequent blending until the sample was well mixed into MP. The MP was then mixed with guar gum at concentrations of 0, 1, 1.25, 1.5, and 1.75% w/w and labeled as MP 0, MP 1, MP 1.25, MP 1.5, and MP 1.75, respectively. The samples were kept at 4 °C overnight before printing, as shown in Figure 1.

2.3. 3D printing

The 3D printer (Shinnove-S2, China) was the extrusion-based printer shown in Figure 2b. The MPs prepared with different concentrations of guar gum were inserted into a syringe manually, and the syringe was inserted into the barrel of the 3D printer. The MP was printed into a square sample having dimensions of 12.5 mm × 12.5 mm × 25 mm with a printing speed of 17.5 mm/s, nozzle size of 1.0 mm, layer height of 0.7 mm, and infill percentage of 50% as printing parameters.

2.4. Proximate analysis

Proximate analysis was performed by adopting the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) methods. Specifically, the water content was evaluated through drying, the protein content was evaluated adopting the Kjeldahl method, the total fat content was evaluated through acid hydrolysis and solvent extraction, the carbohydrate content was evaluated adopting the difference method, and the ash and mineral contents were evaluated through dry ashing [22].

2.5. Rheological properties

A HAAKE MAR III rheometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to measure the rheological properties of the MPs, adopting two parallel plates (P35 Ti L) [23]. Approximately 5 grams of each MP was placed on the bottom plate. The measurement was performed at 25 °C.

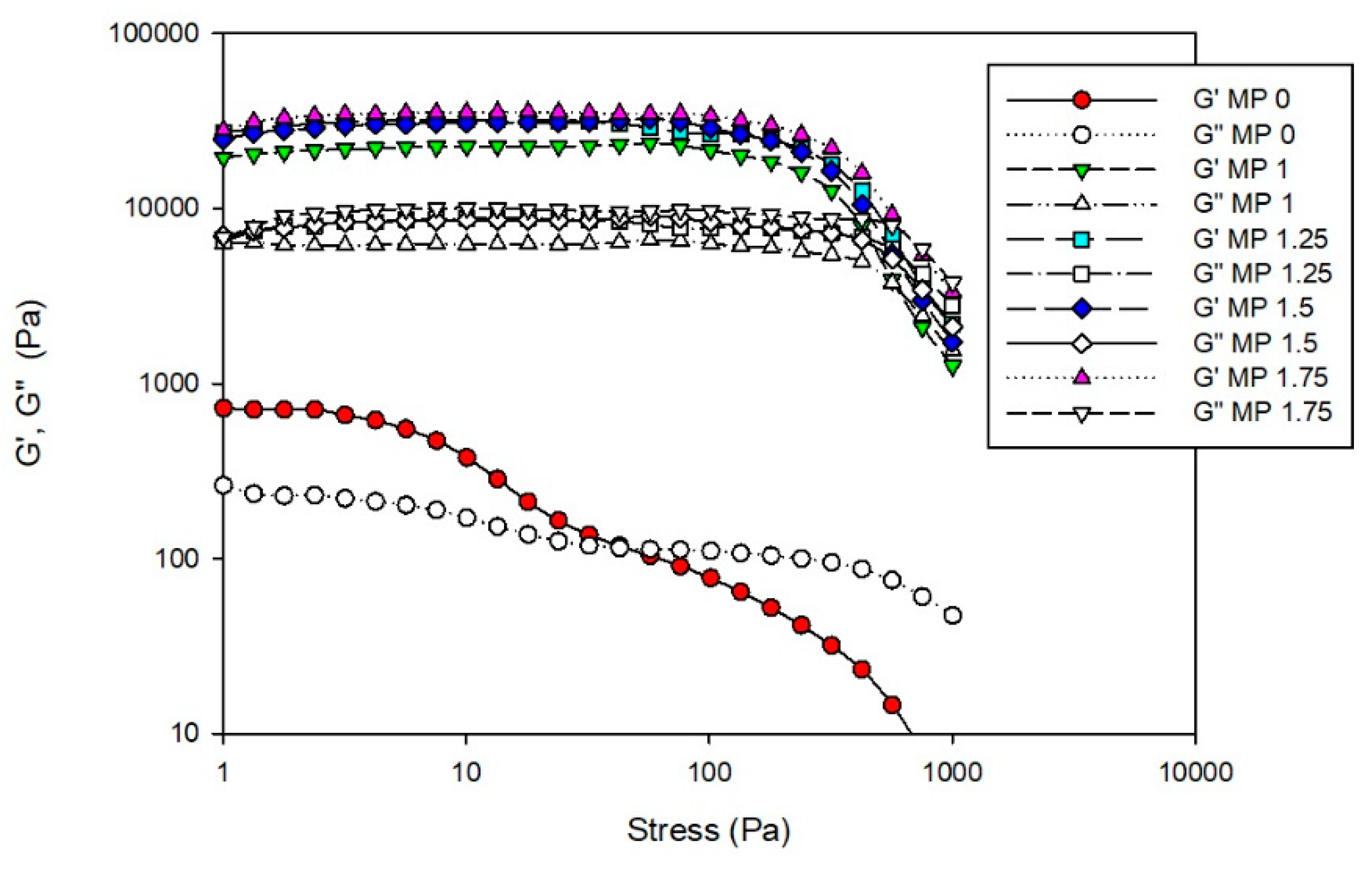

2.5.1. Yield stress

The yield stress was obtained by applying an oscillatory shear stress having a frequency of 1 Hz and increasing from 1 to 1500 Pa at a temperature of 25 °C. The cross-over point between G′ and G” was taken as the yield stress of the MP [24].

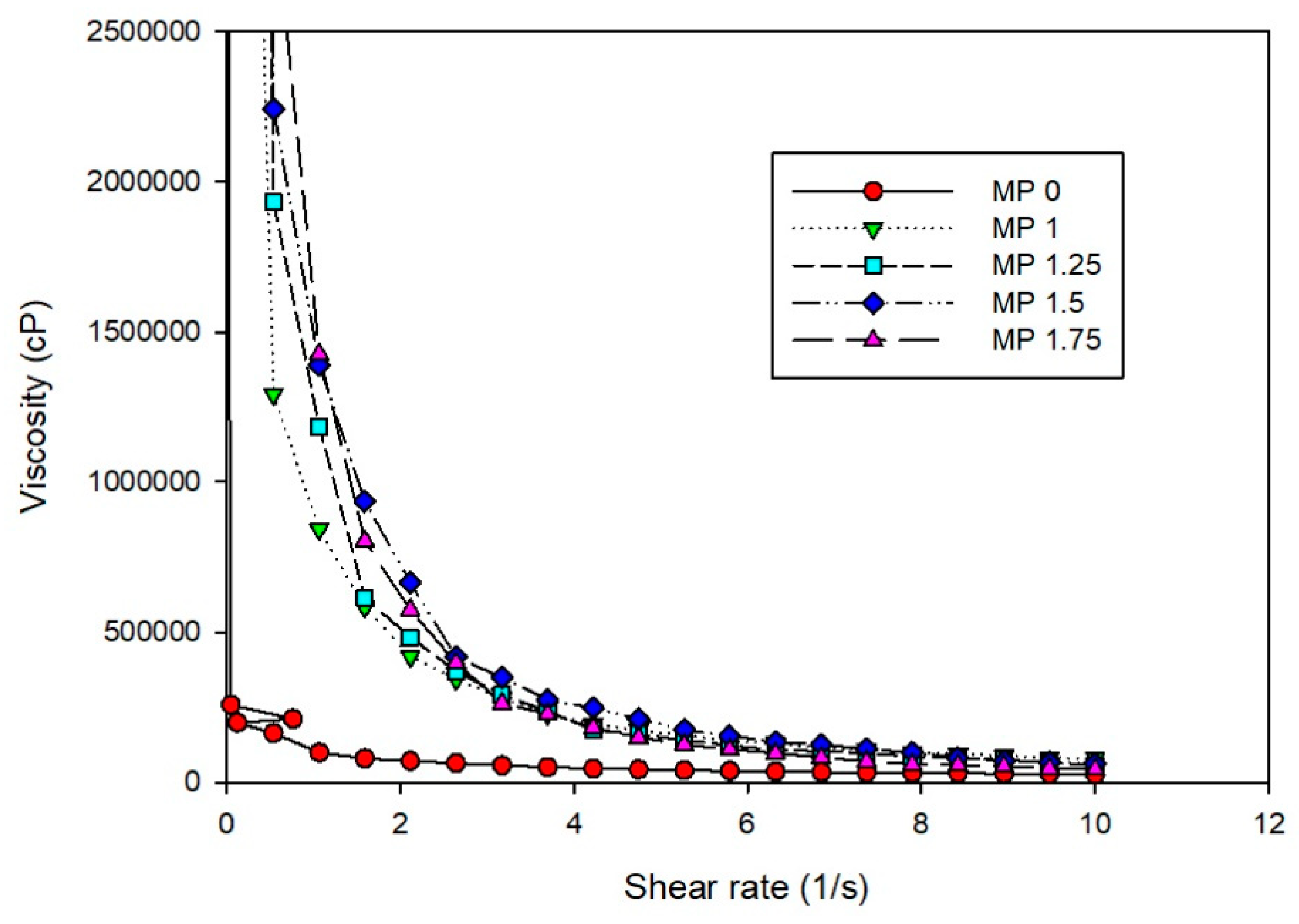

2.5.2. Shear thinning behavior

The shear thinning behavior was measured by adopting a shear rate ranging from 0.01 to 10/s at a temperature of 25 °C to estimate the viscosity of the MP during the printing process. The relationship between the shear rate and viscosity follows the equation of the Ostwald de Waale model [25]:

where η is the viscosity (Pa⋅s), Κ is the consistency index (Pa⋅sn), γ is the shear rate (1/s), and n is the flow behavior index. The correlation coefficient (R2) of the model exceeded 0.99.

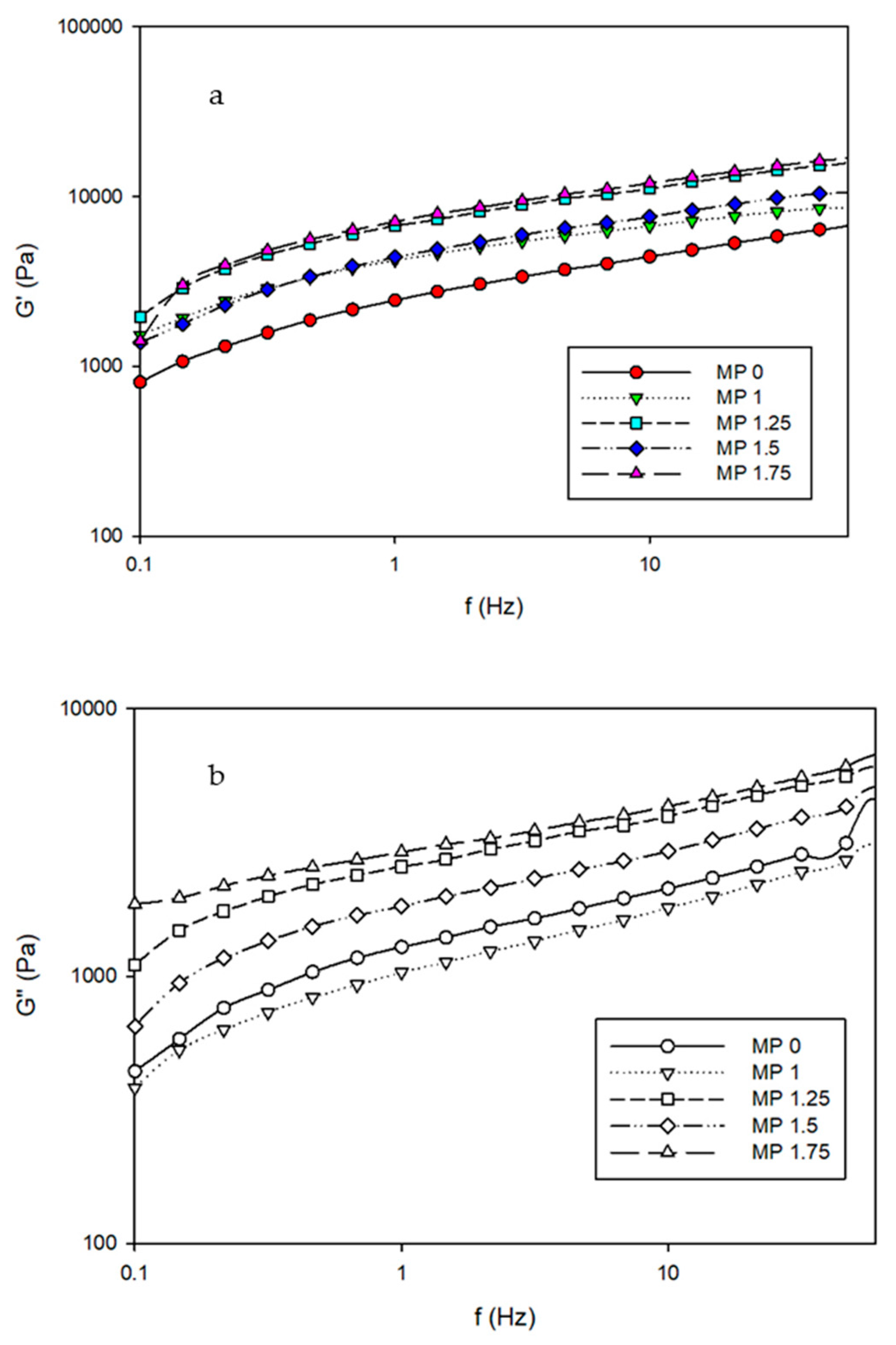

2.5.3. Frequency sweep

A frequency sweep was conducted from 0.1 to 100 rad/s at 1% invariant strain to estimate the linear viscoelastic region of the MPs in the printing process. The G′ and G” values were recorded. A power law model was used to determine the frequency dependence of G′ and G′′ of the sample [26]:

where k′ and k” are model parameters (Pa/sn), f is the frequency (Hz), and m′ and m” are indices of the dimensionless frequency. The correlation coefficient (R2) exceeded 0.99.

2.6. Stability

A square model, with dimensions of 12.5 mm × 12.5 mm × 25 mm, was used in printing. Guar gum concentrations of 0%, 1%, 1.25%, 1.5%, and 1.75% w/w, nozzle sizes of 1.0, 1.3, and 1.6 mm, and infill percentages of 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% were set as the printing parameters affecting stability. The size of the nozzle refers to the width of the hole at the tip of the extruder and the infill percentage refers to the ratio of MP fill inside the printed sample. The sample height was measured immediately after printing using a digital vernier. This moment is considered to be time zero. The height was measured again after the sample had been left at room temperature for 30 minutes. The stability of the MP sample was calculated as [24]

where H30 is sample height (mm) 30 min after printing and H0 is the sample height (mm) 0 min after printing.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate analysis and feasibility for space missions

The results of the proximate analysis of the dried mealworm (Table 1) show that the dried mealworm had a rich protein content. The protein content of the dried mealworm is similar to the crude protein content of mealworm reported by Chewaka et al. [3]. The food system investigated in the present study is thus representative of food systems with high protein contents. The MP contained approximately 24 grams of protein per 100 grams as calculated adopting the Kjeldahl method. Jones [9] calculated the total consumption of protein by 160 crew members on a long-duration space mission as 8160 grams per day. This calculation was based on the Institute of Medicine’s recommended protein intakes for men and women aged 17–90 years of 56 and 46 grams per day, respectively [27]. In that scenario, the consumption of MP would be 34,000 grams per day or 212.5 grams per person, which is approximately 106 grams of dried mealworm per person. Meanwhile, the Deep Space Food Challenge (DSFC) requires four crew members to be fed on a mission lasting 3 years [28]. The requirement of dried mealworm on such a mission would be 446,760 grams according to the DSFC’s criteria. It would thus be possible to design a mealworm farm to be used in space to meet the protein needs of crew members depending on the mission duration and number of crew members.

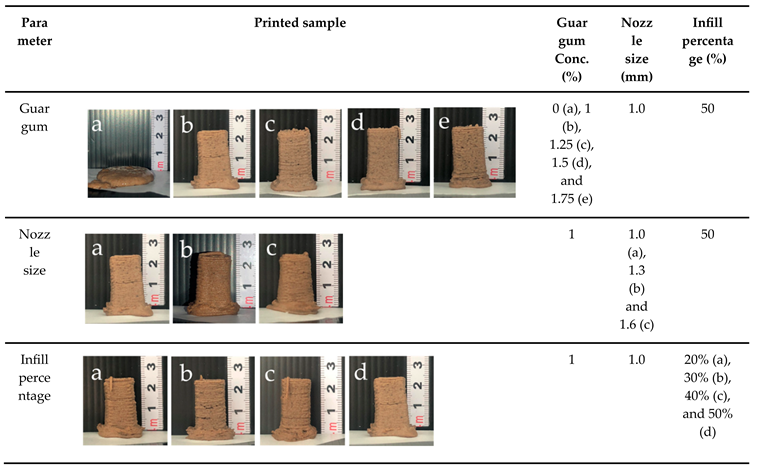

However, through the drying process, some proteins lose their gelling properties [29], causing the MP to lose its abiltity to support itself and maintain its shape, as shown in Table 2. This poses an obstacle to 3D printing. A thickening agent is thus needed to improve printability. It has been suggested that guar gum has the potential to improve rheological properties. Sánchez et al. [30] studied the rheological properties and water binding capacity of food gums mixed with isolated soy protein. They found that soy protein acts synergistically with guar gum, increasing the consistency coefficient of the mixed system by 81% to 139% through shear thinning behavior. They also obtained a high water binding capacity (40 ml/g) owing to the interaction of the soy protein and guar gum. Their results thus show the feasibility of using guar gum to improve the rheological properties of a system having a high protein content.

3.2. Rheological properties

3.2.1. Yield stress

The yield stress represents the minimum force required to initiate fluid flow and thus the carrying capacity of the stacked layer of the filament [31]. Figure 3 presents the cross-over points of G’ and G” (where G’ is equal to G”) of the MPs. It is seen that the yield stress of the MPs increased from 39 Pa for MP 0 to 1096 Pa for MP 1.75. Increasing the guar gum concentration thus resulted in a higher yield stress of the MP and thus a higher minimum force required to extrude the sample from the extruder in the printing process and greater ability to stack layers. In addition, Figure 6 presented later in the paper shows that increasing the guar gum concentration resulted in higher stability. The observed yield stress has a trend similar to that obtained by Lee and Chang [32], who studied the effect of the guar gum concentration on the rheological properties of yogurt made from skim milk, which contains much protein; i.e., Lee and Chang found that increasing the guar gum concentration increased the yield stress. This result may be due to the interaction between protein and guar gum.

3.2.2. Shear thinning behavior

A shear thinning behavior is important to printability. The printing material should have a viscosity at a high shear rate sufficiently low to allow the material to flow through the nozzle tip. Still, the material has to recover viscosity during the deposition stage to support the structure [33]. Figure 4 shows that all the MP samples in the present study exhibited a non-Newtonian shear thinning behavior, with guar gum supplementation strengthening the behavior. An MP is thus extruded more easily from the nozzle tip by adding guar gum to the formulation. At the same shear rate, an increase in the concentration of guar gum increases the viscosity of the MP. Owing to the increased hydrogen bonding activity of the guar gum due to the hydroxyl group of the guar gum molecule [34], a small amount of guar gum notably affects the electrokinetic properties of the system [35].

3.2.3. Frequency sweep

The viscoelastic properties of the MP samples in the deposition stage were obtained in a frequency sweep. The G’ value of the MPs increased from 803 to 10,761 Pa for MP 0 and from 1407 Pa to 20,028 Pa for MP 1.75 with the frequency increasing from 0.1 to 100 Hz as shown in Figure 5a whereas the G” value increased from 440 to 3313 Pa for MP 0 and from 1861 Pa to 4594 Pa for MP 1.75 as shown in Figure 5b. Continuous molecular interactions result in high values of G’ and G” [36]. MP 0, which did not contain guar gum, had the lowest G’ value, which suggests that MP 0 was the weakest of the MPs. The increases in G’ and G” with frequency indicate that an increase in the guar gum concentration strengthens an MP and enables self-support after the deposition stage. The stability results presented in Figure 6 have a similar trend, in that increasing the guar gum concentration stabilized the MP samples after printing. The results of the present study have a trend similar to the results of Dick et al. [21], who studied the printability and rheological properties of pork for dysphagia patients and found that G’ and G” value with the additional guar gum.

The proximate analysis (Table 1) shows that the MPs had high protein content. The strength of the gel may therefore be due to the interaction between the galactomannan of the guar gum and protein, strengthening the network structure of the system [37]. The frequency sweep results indicate that G’ increased with the concentration of guar gum, possibly owing to the network structure of galactomannan and protein and hydrogen bonds. Lei et al. [38] studied the effect of guar gum on the linear rheological properties of phycocyanin and found that samples containing guar gum had higher G’ and G”. Still, as the concentration increased, G’ and G” decreased owing to the increased entanglement of galactomannan chains, which prevented interaction with proteins. This result is consistent with the results of the present study in that MP 1.5 had a low value of G’, which may be due to less interaction between galactomannan and protein, whereas MP 1.75 had a high value G’, presumably because of greater hydrogen bonding.

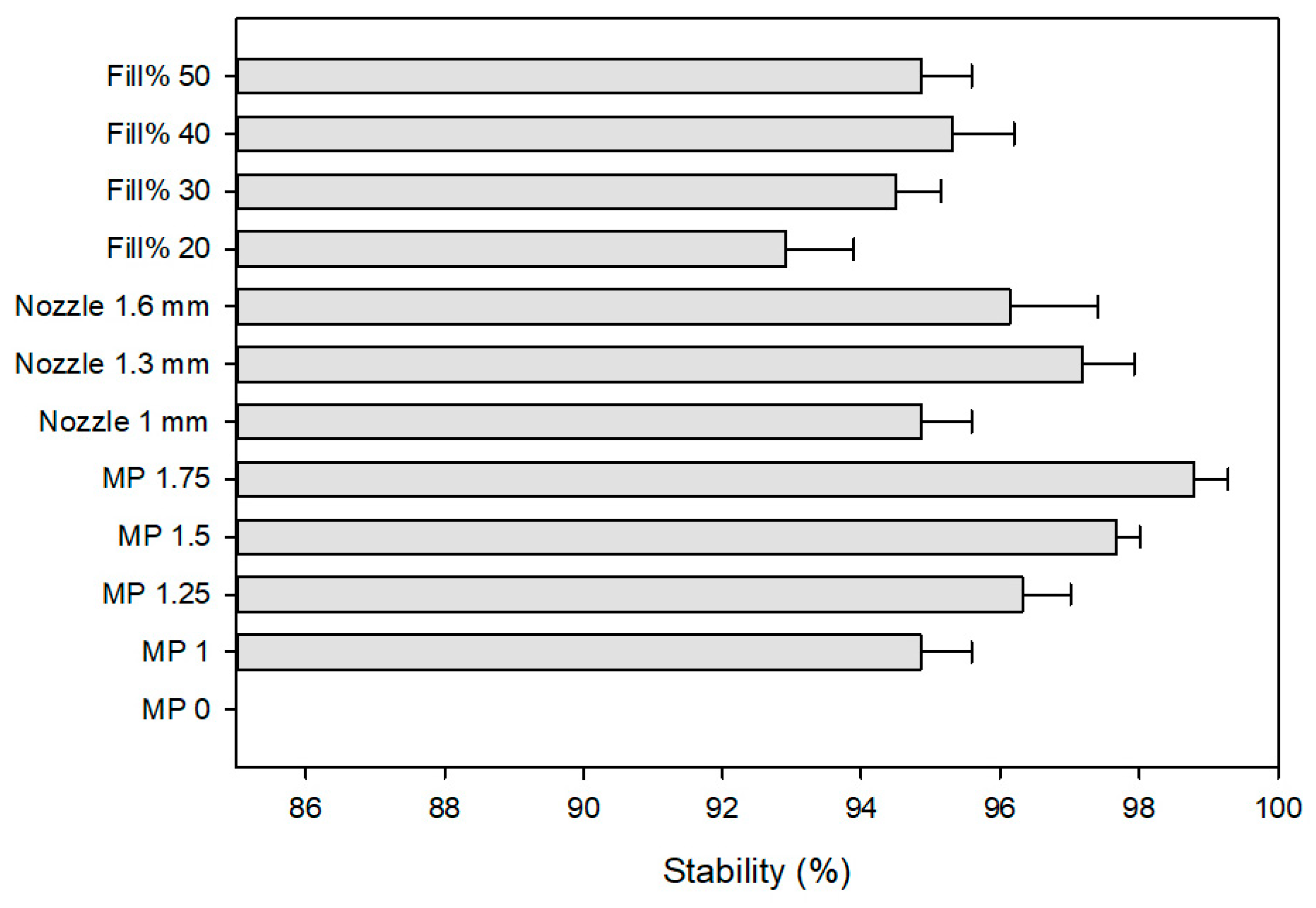

3.3. Stability

Figure 6 shows the stability of the MPs printed and left at room temperature for 30 mins. It is seen that increasing the guar gum concentration resulted in a more stable MP, which relates to the yield stress result that increasing the guar gum concentration made it easier to stack layers of an MP. The printing of MPs using nozzles of different size revealed that the sample printed with a nozzle size of 1.3 mm had the highest stability. The printing of MPs with different infill percentages showed that the sample printed with an infill percentage of 40% had the highest stability. The printed sample without guar gum (MP 0) could not support itself, resulting in the collapse of the structure in the deposition stage. Increasing the guar gum concentration improved the self-support of the MPs. This result is supported by the yield stress and frequency sweep results presented in Figure 3 and Figure 5, which showed that sample MP 0 had the lowest yield stress and lowest G’ and thus the lowest printability.

The above results reveal that the sample printed with a nozzle size of 1.3 mm and infill percentage of 40% had the best stability, and MP 1.75 had the best stability and rheological properties. Thus, MP 1.75 printed with a nozzle size of 1.3 mm and infill percentage of 40% had the best printability.

4. Conclusion

This study found that introducing guar gum enhanced the printability of MP. Increasing the concentration of guar gum increased the MP yield stress, which resulted in a stronger force being required to push the MP out of the extruder and more layers of the MP able to be stacked. Moreover, the addition of guar gum provided the MP with non-Newtonian rheological properties. An additional of guar gum concentration could cause more shear thinning behavior and enhance the viscoelastic properties of the MP such that the MP maintained its shape after printing. In addition, increasing the guar gum concentration increased the MP stability. Furthermore, printing parameters affected the printability of the MPs. The MP printed with a nozzle size of 1.3 mm and infill percentage of 40% was the most stable. In summary, introducing guar gum provided MP rheological properties that were more suitable for printing, such that the MP had better printability and stability.

The high protein contents of MPs means that MPs are suited to the production of deep-space food on long-duration space missions. However, the present study investigated only the printability and feasibility of MP in a model system to understand the rheological behaviors of a food system having a high level of protein. Further research on the properties of mealworm mixed with guar gum and clinical trial tests involving personal nutrition are required to understand the shear recovery rate and texture profile. Furthermore, MP recipes need to be used in complex systems in future 3D food printing and deep-space food research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, War.C., Wan.C. and P.N.; methodology, War.C., Wan.C. and P.N.; investigation, Y.K. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, War.C., Y.K., Wan.C., P.N. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, War.C., Y.K., Wan.C., P.N. and J.W.; supervision, War.C., Wan.C. and P.N.; project administration, War.C.; Funding Acquisition, War.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is supported by the Chulabhorn Royal Academy (Fundamental Fund: Fiscal Year 2023 of the National Science Research and Innovation Fund (FRB660044/0240 Project code 180847)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the KEETA team from Thailand for the Deep Space Food Challenge (DSFC), organized by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), for the initiative’s conceptual idea and for raising funding. We thank Edanz (www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing conflicts of interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Van Huis, A.; Oonincx, D.G.A.B. The environmental sustainability of insects as food and feed. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Nutritional composition and safety aspects of edible insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chewaka, L.S.; Park, C.S.; Cha, Y.-S.; Desta, K.T.; Park, B.-R. Enzymatic hydrolysis of Tenebrio molitor (mealworm) using nuruk extract concentrate and an evaluation of its nutritional, functional, and sensory properties. Foods 2023, 12, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendin, K.; Olsson, V.; Langton, M. Mealworms as food ingredient—Sensory investigation of a model system. Foods 2019, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djouadi, A.; Sales, J.R.; Carvalho, M.O.; Raymundo, A. Development of healthy protein-rich crackers using Tenebrio molitor flour. Foods 2022, 11, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H. Feasibility of feeding yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L. ) in bioregenerative life support systems as a source of animal protein for humans, Acta Astronaut. 2013, 92, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, K. et al. Growth optimization and rearing of mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) as a sustainable food source. Foods 2023, 12, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Piccione, R. et al., Sustaining human life in space. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (España), 2021.

- Jones, R.S. Space diet: daily mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) harvest on a multigenerational spaceship. J. Interdiscip. Sci. Top. 2015, 4, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, R.; Van Huis, A. Insect food in space. J. Insects Food Feed 2021, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terfansky, M.L.; Thangavelu, M. 3D Printing of Food for Space Missions. In AIAA SPACE 2013 Conference and Exposition, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: San Diego, CA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Godoi, F.C.; Prakash, S.; Bhandari, B.R. 3D printing technologies applied for food design: Status and prospects. J. Food Eng. 2016, 179, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.; Srivastava, M. Emerging sustainable supply chain models for 3D food printing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Dong, X. Bhandari, B. Prakash, S. The role of hydrocolloids on the 3D printability of meat products. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 119, 106879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B. Materials properties of printable edible inks and printing parameters optimization during 3D printing: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3074–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Regenstein, J. M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, P. Rheological and mechanical behavior of milk protein composite gel for extrusion-based 3D food printing. LWT 2019, 102, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamipour-Shirazi, A.; Norton, I.T.; Mills, T. Designing hydrocolloid based food-ink formulations for extrusion 3D printing. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whistler, R.L.; Hymowitz, T. Guar: Agronomy, Production, Industrial Use, and Nutrition. Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, Ind, 1979.

- Wu, M. Shear-thinning and viscosity synergism in mixed solution of guar gum and its etherified derivatives. Polym. Bull. 2009, 63, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Bae, H.; Park, H.J. Classification of the printability of selected food for 3D printing: Development of an assessment method using hydrocolloids as reference material. J. Food Eng. 2017, 215, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Bhandari, B.; Dong, X.; Prakash, S. Feasibility study of hydrocolloid incorporated 3D printed pork as dysphagia food. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 107, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuniff, P. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. AOAC International, 1997.

- Dick, A.; Bhandari, B.; Prakash, S. Printability and textural assessment of modified-texture cooked beef pastes for dysphagia patients. Future Foods 2021, 3, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. et al., Improvement of rheological properties and 3D printability of pork pastes by the addition of xanthan gum. LWT 2023, 173, 114325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, R.A.; Bártolo, P.J.; Mendes, A.; Filho, R.M. Rheological behavior of alginate solutions for biomanufacturing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 3866–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Wang, C.; Yuan, D.; Kong, B.; Sun, F.; Liu, Q. Effects of acetylated cassava starch on the physical and rheological properties of multicomponent protein emulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 1459–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine, Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- NASA Begins Final Phase of $3 Million Deep Space Food Challenge | NASA. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/spacetech/centennial_challenges/press-release/nasa-begins-final-phase-of-3-million-deep-space-food-challenge (accessed on Sep. 26, 2023).

- Mauer, L. PROTEIN | Heat treatment for food proteins. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition, Elsevier, 2003, pp. 4868–4872. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, V.E.; Bartholomai, G.B.; Pilosof, A.M.R. Rheological properties of food gums as related to their water binding capacity and to soy protein interaction. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, N.; Smolan, W.; Böck, T.; Melchels, F.; Groll, J.; Jungst, T. Proposal to assess printability of bioinks for extrusion-based bioprinting and evaluation of rheological properties governing bioprintability. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 044107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Chang, Y.H. Influence of guar gum addition on physicochemical, microbial, rheological and sensory properties of stirred yoghurt. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016, 69, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lille, M.; Nurmela, A.; Nordlund, E.; Metsä-Kortelainen, S.; Sozer, N. Applicability of protein and fiber-rich food materials in extrusion-based 3D printing. J. Food Eng. 2018, 220, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhanjan, H.; Gharia, M.M.; Srivastava, H.C. Guar gum derivatives. Part I: Preparation and properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 1989, 11, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glicksman, M. Gum Technology in the Food Industry, 1969.

- Wu, M.; Xiong, Y.L.; Chen, J.; Tang, X.; Zhou, G. Rheological and microstructural properties of porcine myofibrillar protein-lipid emulsion composite gels. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, E207–E217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C.; Monteiro, S.R.; Moreno, N.; Lopes Da Silva, J.A. Does the branching degree of galactomannans influence their effect on whey protein gelation? Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2005, 270–271, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Effects of κ-carrageenan and guar gum on the rheological properties and microstructure of phycocyanin gel. Foods 2022, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mealworm paste preparation and the three-dimensional printing process.

Figure 2.

(a) Dried mealworm and (b) Foodbot Shinnove-S2 three-dimensional printer.

Figure 3.

Effect of the guar gum concentration on the yield stress of MP at 25 °C. The yield stress values are the cross-over points of G′ and G′′.

Figure 3.

Effect of the guar gum concentration on the yield stress of MP at 25 °C. The yield stress values are the cross-over points of G′ and G′′.

Figure 4.

Effect of the guar gum concentration and shear rate on the viscosity of MP at 25 °C.

Figure 5.

Effects of the concentration of guar gum and frequency on G’ for MPs at 25 °C (a). Effects of the concentration of guar gum and frequency on G” for MPs at 25 °C (b).

Figure 5.

Effects of the concentration of guar gum and frequency on G’ for MPs at 25 °C (a). Effects of the concentration of guar gum and frequency on G” for MPs at 25 °C (b).

Figure 6.

Stability of MP 0, MP 1, MP 1.25, MP 1.5, and MP 1.75 and the effects of the nozzle size (1, 1.3, and 1.6 mm) and infill percentage (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%) on stability.

Figure 6.

Stability of MP 0, MP 1, MP 1.25, MP 1.5, and MP 1.75 and the effects of the nozzle size (1, 1.3, and 1.6 mm) and infill percentage (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%) on stability.

Table 1.

Proximate analysis of dried mealworm.

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Moisture (% wet basis) | 6.07 ± 0.04 |

| Crude protein (g/100 g) | 47.70 ± .0.38 |

| Crude fat (g/100 g) | 30.50 ± 0.39 |

| Crude fiber (g/100 g) | 6.02 ± 0.07 |

| Ash (g/100 g) | 3.47 ± 0.09 |

| Carbohydrate (g/100 g) | 6.24 |

Table 2.

Summary of MPs printed with dimensions of 12.5 mm × 12.5 mm × 25 mm.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated