Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

04 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validation process

3.1.1. Construct validation and understanding

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

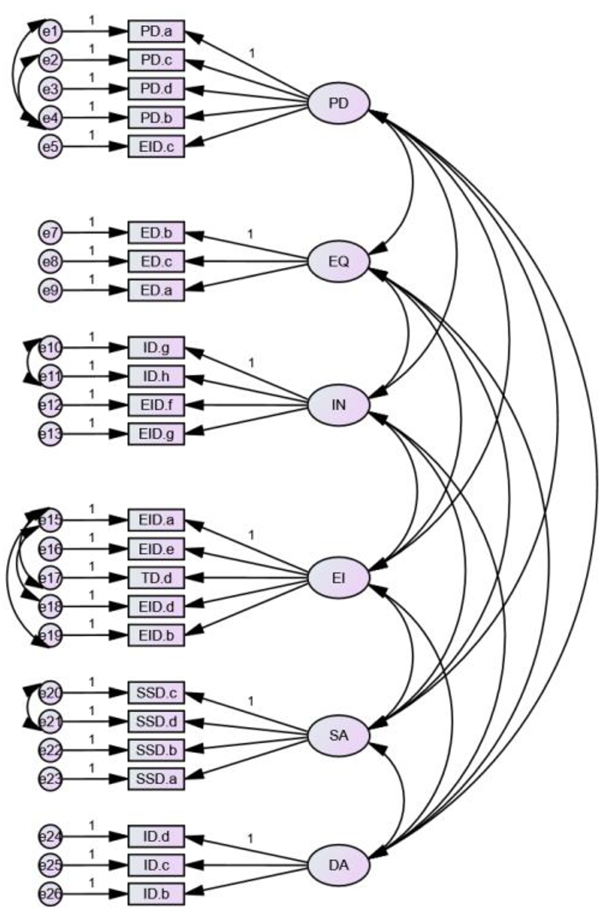

3.2. Confirmatory analysis

| DIMENSIONS | CODES | FACTORIAL LOADINGS | ADJUSTED MODEL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory Empowerment | PD.a | 0.720 |  |

| PD.c | 0.620 | ||

| PD.d | 0.780 | ||

| PD.b | 0.520 | ||

| EID.c | 0.560 | ||

| Equality | ED.b | 0.960 | |

| ED.c | 0.830 | ||

| ED.a | 0.800 | ||

| Independence | ID.g | 0.480 | |

| ID.h | 0.500 | ||

| EID.f | 0.890 | ||

| EID.g | 0.890 | ||

| External Influences | EID.a | 0.430 | |

| EID.e | 0.620 | ||

| TD.d | 0.450 | ||

| EID.d | 0.670 | ||

| EID.b | 0.510 | ||

| Social Satisfaction | SSD.c | 0.510 | |

| SSD.d | 0.450 | ||

| SSD.b | 0.580 | ||

| SSD.a | 0.710 | ||

| Dependant Attitudes | ID.d | 0.780 | |

| ID.c | 0.670 | ||

| ID.b | 0.530 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment Theory. Handbook of Community Psychology, 1984, 43–63.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas. (1995). Declaración y Plataforma de Acción de Beijing. In La Cuarta Conferencia Mundial sobre la Mujer.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas. (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (1999a). Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. [CrossRef]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas. (2019). Informe de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 2019. In Informe de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 2019. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2018-ES.pdf.

- Weldon, S. L. (2019). Power, exclusion and empowerment: Feminist innovation in political science. Women's Studies International Forum, 72(June 2018), 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, S. (1994). Women's Interests and Empowerment: Gender Planning Reconsidered. Development and Change, 25(4), 829–848. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (1997). 'Can buy me love'? Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies ,. IDS Discusion Paper 363, 1–89. http://www.ids.ac.uk/idspublication/money-can-t-buy-me-love-re-evaluating-gender-credit-and-empowerment-in-rural-bangladesh.

- Malhotra, A., & Schuler, S. R. (2005). Women's empowerment as a variable in International Development. World Bank.Org, 71–88. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BzXyApyTGOYC&pgis=1.

- Kabeer, N. (1999b). Resources, Agency, Achievements : Re ¯ ections on the Measurement of Women' s Empowerment. 30(May), 435–464.

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women's empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal 1. Gender & Development, 13(1), 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, E. , & Lamelas, N. (2012). Midiendo el empoderamiento femenino en América Latina. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 12, 153–158. [CrossRef]

- Marinho, P. A. S. , & Gonçalves, H. S. (2016). Práticas de empoderamento feminino na América Latina. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 2016(56), 80–90. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, T. , & Moore, M. (1983). On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India Author ( s ): Tim Dyson and Mick Moore Source : Population and Development Review, Vol. 9, No. 1 ( Mar., 1983 ), pp. 35-60 Published by : Population Council Stable URL : http. Lancet, 09(1), 35–60.

- Jejeebhoy, S. J. , & Sathar, Z. A. (2001). Women's autonomy in India and Pakistan: The influence of religion and region. Population and Development Review, 27(4), 687–712. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A., & Schuler, S. R. (2005). Women's empowerment as a variable in International Development. World Bank.Org, 71–88. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BzXyApyTGOYC&pgis=1.

- Peterman, A. , Pereira, A., Bleck, J., Palermo, T. M., & Yount, K. M. (2017). Women's individual asset ownership and experience of intimate partner violence: Evidence from 28 international surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 107(5), 747–755. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A. L. , & Gottlieb, J. (2021). How to Close the Gender Gap in Political Participation: Lessons from Matrilineal Societies in Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 68–92. [CrossRef]

- Giuri, P., Grimaldi, R., Kochenkova, A., Munari, F., & Toschi, L. (2020). The effects of university-level policies on women's participation in academic patenting in Italy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(1), 122–150. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2001). Discussing Women' s Empowerment: Theory and Practice. SIDA Studies, 136. www.sida.se.

- Vissandjee, B. Apale, A., Wieringa, S., Abdool, S., & Dupéré, S. (2005). Empowerment beyond numbers: Substantiating women's political participation. Journal of International Women's Studies, 7(2), 123–139. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-29144471320&partnerID=tZOtx3y1.

- Jung, D. , & Sosik, J. J. (2002). Transformational leadership in work groups: The role of empowerment, cohesiveness, and collective-efficacy on perceived group performance. Small Group Research, 33(3), 313–336. [CrossRef]

- Bin Bakr, M. , & Alfayez, A. (2021). Transformational leadership and the psychological empowerment of female leaders in Saudi higher education: an empirical study. Higher Education Research and Development, 0(0), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Diehl, A. B. , & Dzubinski, L. M. (2016). Making the invisible visible: A Cross-Sector Anlysis of Gender-Based Leadership Barriers. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 2(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ambri, S., Tahir, L. M., & Alias, R. A. (2018). An Overview of Glass Ceiling, Tiara, Imposter, and Queen Bee Barrier Syndromes on Women in the Upper Echelons. Asian Social Science, 15(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Mavin, S. (2008). Queen bees, wannabees and afraid to bees: No more "best enemies" for women in management? British Journal of Management, 19(SUPPL. 1). [CrossRef]

- Dudău, D. P. (2014). The Relation between Perfectionism and Impostor Phenomenon. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 127, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Albert, C. , & Escardíbul, J.-O. (2017). Education and the empowerment of women in household decision-making in Spain. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(2), 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2012b). Women's economic empowerment and inclusive growth: labour markets and enterprise development. International Development Research Centre, 44(0), 1–70.

- Borghei, N. S. , Taghipour, A., Latifnejad Roudsari, R., & Keramat, A. (2015). Development and validation of a new tool to measure Iranian pregnant women's empowerment. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 21(12), 897–905. [CrossRef]

- Shuja, K. H. , Aqeel, M., & Khan, K. R. (2020). Psychometric development and validation of attitude rating scale towards women empowerment: across male and female university population in Pakistan. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 13(5), 405–420. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1985). The Dewey Lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221.

- Donald, A. , Koolwal, G., Annan, J., Falb, K., & Goldstein, M. (2020). Measuring Women's Agency. Feminist Economics, 26(3), 200–226. [CrossRef]

- Pick, S., Sirkin, J., Ortega, I., Osorio, P., Martínez, R., Xocolotzin, U., & Givaudan, M. (2007). Escala para medir agenda personal y empoderamiento (ESAGE). Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 41(3), 295–304. http://search.proquest.com/docview/622125339?accountid=10422.

- Yount, K. M. , James-Hawkins, L., & Abdul Rahim, H. F. (2020). The Reproductive Agency Scale (RAS-17): Development and validation in a cross-sectional study of pregnant Qatari and non-Qatari Arab Women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Ruth A, Worthington. Anderson, Wiliam T. & Jennings, G. (1994). The Developtment of an Autonomy Scale. Contemporary Family Therapy, 16(4), 329–345.

- Gram, L. , Morrison, J., Sharma, N., Shrestha, B., Manandhar, D., Costello, A., Saville, N., & Skordis-Worrall, J. (2017). Validating an Agency-based Tool for Measuring Women's Empowerment in a Complex Public Health Trial in Rural Nepal. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 18(1), 107–135. [CrossRef]

- 김안나 & 최승아. (2013). 결혼이주여성 임파워먼트 척도 개발에 관한 연구. 한국여성학, 29(2), 189–229.

- Hernández, J., & Falconi, R. (2008). Instrumento para medir el empoderamiento de la mujer. http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/documentos_download/101158.pdf.

- Solis, U. (2003). El enfoque de derechos: aspectos teóricos y conceptuales (pp. 1–19).

- Padilla, N. , & Cruz, C. (2018). Validación de una escala de empoderamiento y agencia personal en mujeres mexicanas. Revista Digital Internacional de Psicología y Ciencia Social, 4(1), 28–45. [CrossRef]

- Padilla Gámez, N. , Pérez Bautista, Y. Y., & Cruz del Castillo, C. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión corta de la escala de Empoderamiento y Agencia Personal en estudiantes universitarios. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 12(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Canaval, G. E. (1999). Propiedades psicométricas de una escala para medir percepción del empoderamiento comunitario en mujeres. Colombia Medica, 30(2).

- Quijano-Ruiz, A. , & Faytong-Haro, M. (2021). Maternal sexual empowerment and sexual and reproductive outcomes among female adolescents: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in Ecuador. SSM - Population Health, 14, 100782. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, B. F. , Cabrera, L. Y., Maqueda, R. H., Ballesteros, I., & del Moral, F. (2020). Case study on empowerment with women in Ecuador: Elements for a socio-educational intervention. Revista Internacional de Educacion Para La Justicia Social, 9(2), 151–172. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa Romero, D. (2018). Mujeres Indígenas del Ecuador: la larga marcha por el empoderamiento y la formación de liderazgos. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 43(2), 253–276. [CrossRef]

- Morales, P. (2011). El Análisis Factorial en la construcción e interpretación de tests, escalas y cuestionarios.

- George, D. , & Mallery, P. (2018). IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step. In IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step. [CrossRef]

- Gliem, Joserph A.; Gliem, R. R. (2003). Calculating, Interpreting, and Reporting Cronbach's Alpha Reliability Coefficient for Likert-Type Scales. Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education Calculating,. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, H. , & Campo, A. (2005). Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, XXXIV(1), 571–580. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/806/80634409.pdf%0Ahttp://www.redalyc.org/pdf/806/80650839004.pdf.

- Pérez López, C. (2004). Técnicas de Análisis Multivariante de Datos. Aplicaciones con SPSS.

- Henson, R. K. , & Roberts, J. K. (2006). Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(3), 393–416. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J. J. (2020). Structural equation modelling. Application for Research and Practice.

- Tabri, N. , & Elliott, C. M. (2012). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. In Canadian Graduate Journal of Sociology and Criminology (Vol. 1, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Constitución Política del Ecuador, (2008).

- Ley Orgánica Electoral y Código de Democracia, 1 (2020).

- Ley Orgánica de Educación Superior, 1 Registro Oficial No298 Año1 5 (2010).

- Haque, M., Islam, T. M., Tareque, I., & Mostofa, G. (2011). Women Empowerment or Autonomy : A Comparative View in Bangladesh Context. Bangladesh E-Journal of Sociology, 8(2), 17–30. https://www.bangladeshsociology.net/8.2/2BEJS 8.2-3.pdf.

- Doepke, M. y Tertilt, M. l. (2019). Does Women economic empowerment contribute to economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 24(4), 309–343.

- Humanos, D. E. D. (n.d.). Sistema universal de protección de derechos humanos. 91–130.

- Archenti, N. , & Tula, M. I. (2014). Cambios normativos y equidad de género. De las cuotas a la paridad en América Latina: los casos de Bolivia y Ecuador. América Latina Hoy, 66, 47-68.

- Lagarde, M. (2009). La política feminista de la sororidad. Mujeres En Red. El Peródico Feminsta, 1–5. http://www.mujeresenred.net/spip.php?article1771.

- Segovia-Pérez, M. , Laguna-Sánchez, P., & de la Fuente-Cabrero, C. (2019). Education for Sustainable Leadership: Fostering Women's Empowerment at the University Level Mónica. Sustainability (Switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Arestoff, F. , & Djemai, E. (2016). Women's Empowerment Across the Life Cycle and Generations: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 87, 70–87. [CrossRef]

- Merma-Molina, G. , Urrea-Solano, M., Baena-Morales, S., & Gavilán-Martín, D. (2022). The Satisfactions, Contributions, and Opportunities of Women Academics in the Framework of Sustainable Leadership: A Case Study. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(14). [CrossRef]

- Loor, J. S. , & Rodríguez, M. O. (2018). Representatividad de las mujeres en los organismos de cogobierno de las instituciones de Educación Superior de Ecuador. El caso de la Universidad Laica Eloy Alfaro de Manabí. International Journal for 21st Century Education, 5(1), 52-62. [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, T. T. P. , Sevillano, L. M. C., Mejía, Z. E. H., & Burga, R. E. C. (2022). Liderazgo y empoderamiento en las mujeres empresarias en el Perú. Revista de ciencias sociales, 28(5), 234-245.

- Bel Bravo, M. A. (1998). La mujer en la historia (Ediciones).

- De Beauvoir, S. (1967). Memorias de una joven formal. 187.

| Nº | CODES | ITEMS | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PD.a | To exercise good leadership, I have to be persistent. | 0.736 | |||||

| 2 | PD.c | To exercise good leadership, I have to be very active | 0.729 | |||||

| 3 | PD.d | Do you think it is essential that women have their economic income? | 0.694 | |||||

| 4 | PD.b | To exercise good leadership, I have to be an entrepreneur. | 0.638 | |||||

| 5 | EID.c | Women have the knowledge and skills to participate in positions of power. | 0.498 | |||||

| 6 | TD.c | To exercise political leadership, I need to have the right qualities | 0.421 | |||||

| 7 | ED.b | Women have the same opportunities as men in accessing decision-making positions. | 0.919 | |||||

| 8 | ED.c | Women have the same opportunities to access jobs of all kinds. | 0.864 | |||||

| 9 | ED.a | Women enjoy the same rights as men to obtain positions of power and leadership. | 0.859 | |||||

| 10 | ID.g | I decide when and how to have sex* | 0.799 | |||||

| 11 | ID.h | I decide when and how many children to have. * | 0.798 | |||||

| 12 | EID.f | Women can occupy positions of power and leadership. | 0.595 | |||||

| 13 | EID.g | I want more women to access positions of power. | 0.565 | |||||

| 14 | ID.e | I make decisions about the use and expense of my monthly salary | 0.421 | |||||

| 15 | EID.a | The cultural level influences women to function in positions of power and leadership. | 0.650 | |||||

| 16 | EID.e | The school influences women to be able to function in a position of power or politics. | 0.649 | |||||

| 17 | TD.d | It is better for important decisions to be made by women. | 0.598 | |||||

| 18 | EID.d | The family educates women to have positions of power and leadership. | 0.552 | |||||

| 19 | EID.b | I feel comfortable when I am the object of praise or awards. | 0.535 | |||||

| 20 | SSD.c | I chose my current career or activity without pressure. | 0.681 | |||||

| 21 | SSD.d | My family sees it as good that I participate socially, even though I spend less time with them. | 0.666 | |||||

| 22 | SSD.b | My work is valued and recognized. | 0.661 | |||||

| 23 | SSD.a | I have the necessary skills to participate socially. | 0.530 | |||||

| 24 | ID.d | I try to meet the expectations or desires that my loved ones have for me. | 0.794 | |||||

| 25 | ID.c | My happiness depends on the happiness of those close to me. | 0.794 | |||||

| 26 | ID.b | My parents always have to know where I am. | 0.670 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).