1. Introduction

Liver is the sixth most common site of primary malignancies with nearly 1 million new cases diagnosed each year (4,7% of all sites); liver cancer is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths following lung and colorectal cancers ([

1]). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer, comprising more than 70% of primary liver malignancies, with risk factors widely dependent on geographic and ethnic variations. The most common risk factors are viral hepatitis (HBV, HCV), as well as other known risk factors including aflatoxin, alcohol abuse and smoking, or metabolic disorders such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), obesity and type 2 diabetes ([

1,

2]).

The most common sites of HCC metastasis are lungs, abdominal lymph nodes, adrenal glands and bones, while brain, peritoneum, skin and muscle are rarely affected. ([

3]) Head and neck metastases are extremely rare, with 103 reported cases in the largest literature review so far, from 2007 until now ([

4,

5]). Moreover, the solitary orofacial HCC metastases are extremely rare and they are considered to occur by an alternative hematogenous route and may present the initial symptom of the disease.

We present a rare case of a solitary extrahepatic metastasis of a known HCC in the mandible, confirmed after the core biopsy of the lesion.

2. Case Report

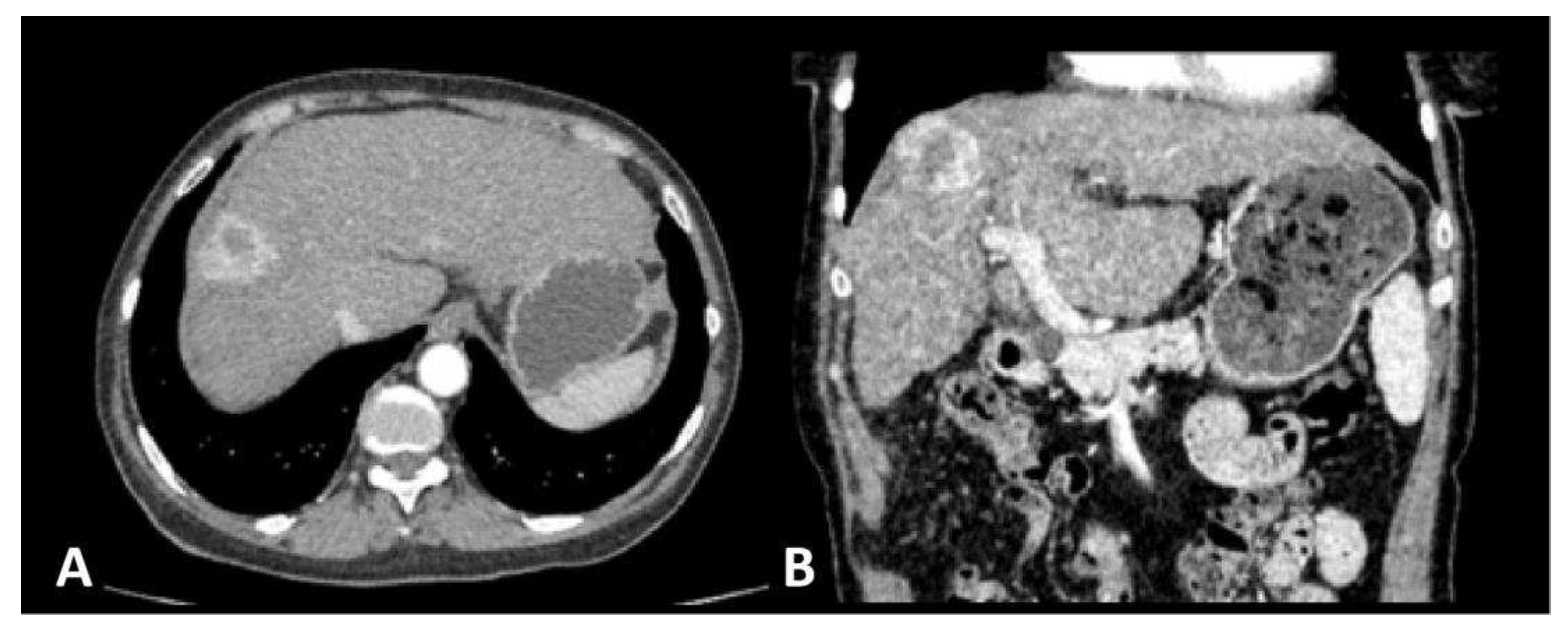

A 65-year old female patient was admitted to the surgical clinic with previously detected Computed Tomography (CT) presentation of a subcapsular 3 cm solitary,

hyper vascular, primary liver tumor in the segment VIII, in the setting of a cirrhotic liver caused by chronic HCV infection, highly suggestive of an HCC (

Figure 1). The CT scan demonstrated signs of portal hypertension, such as recanalization of paraumbilical veins, discrete venous collaterals in the omentum and esophageal varices. Additionally, there was no evidence of extrahepatic disease in the thorax, abdomen or pelvis, nor signs of ascites. Upon admission to the hospital and detailed clinical and laboratory work-up, the patient was classified as Child-Pugh class A, with the following values: total bilirubin level of 20.2 mmol/L, albumin level of 39 g/L, INR of 1.16, without signs of ascites or encephalopathy. Furthermore, the patient’s performance status, assessed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) grading system, was 0. Considering the patients favorable performance status, without comorbidities, and Child Pugh class A, the patient met the stage A criteria by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) and curative-intent surgical intervention (open anatomic resection of liver segment VIII) was performed. The pathohistological (PH) report of the resected specimen confirmed the presence of a moderately differentiated G2 trabecular-type HCC, pathological Tumor-Node-Metastasis (pTNM) staging of IB, with no residues of the tumor on the surgical margin – R0 resection. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged from hospital on postoperative day 7. The first follow-up visit was scheduled for one month and further more on 6 months basis. Given the curative R0 resection, no chemo- or radiotherapy was advised.

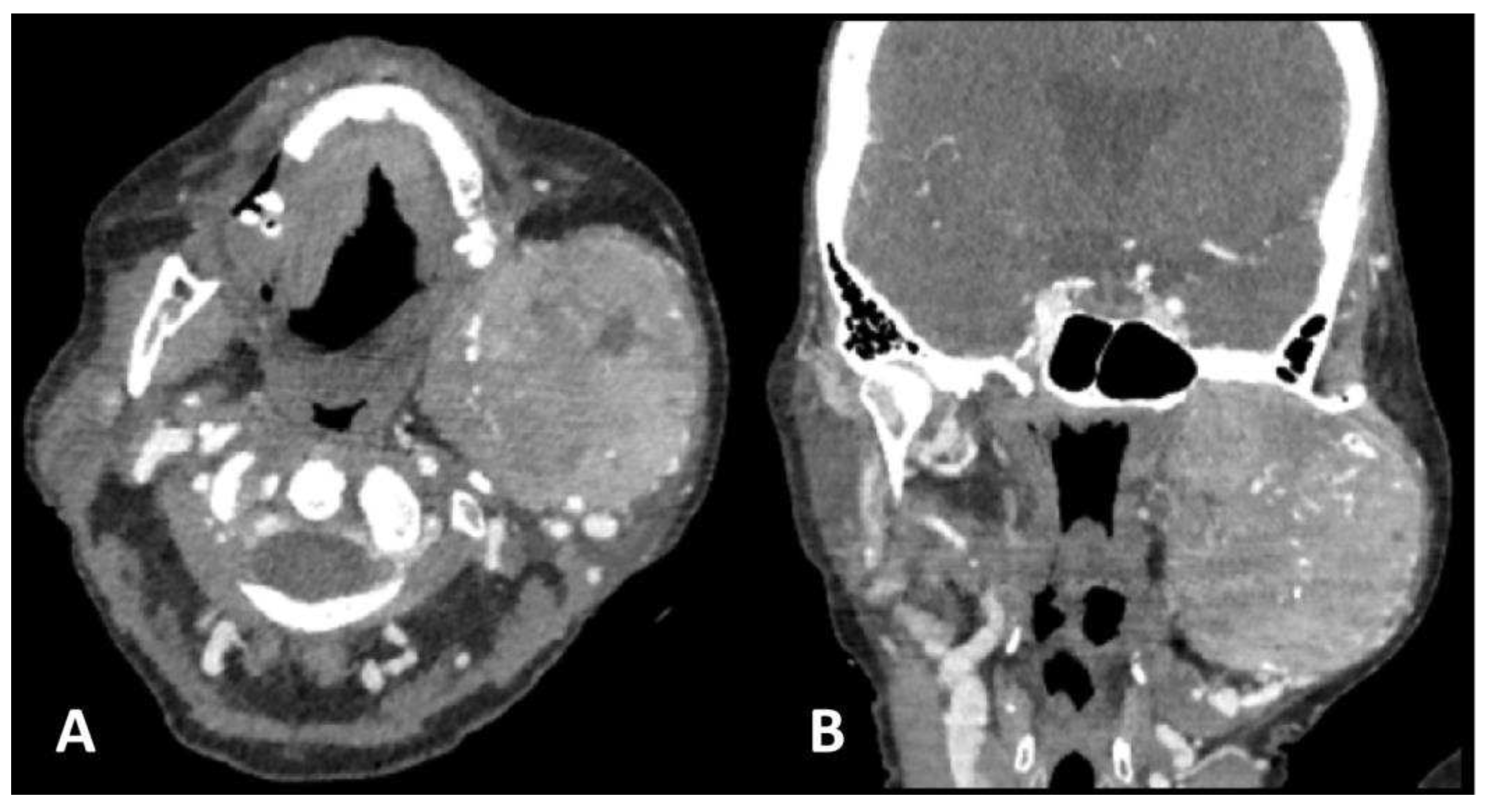

Two months after the initial diagnosis and subsequent liver resection, the patient was admitted to a COVID hospital due to a positive PCR COVID-19 test and the chest X-ray findings of a bilateral pneumonia. At the admission, she reported a diffuse,

firm, and painless swelling of the left jaw which she noticed a week prior to admission and thereafter a neck CT was ordered. The neck CT demonstrated a large osteolytic soft-tissue mass in the left mandibular angle and ramus, spreading to the temporal fossa and parotid area occupying the space from the skull base to the submandibular area. The mass displayed heterogeneous and intense contrast enhancement, along with osteolytic bone changes and infiltration of the masticatory muscles (

Figure 2).

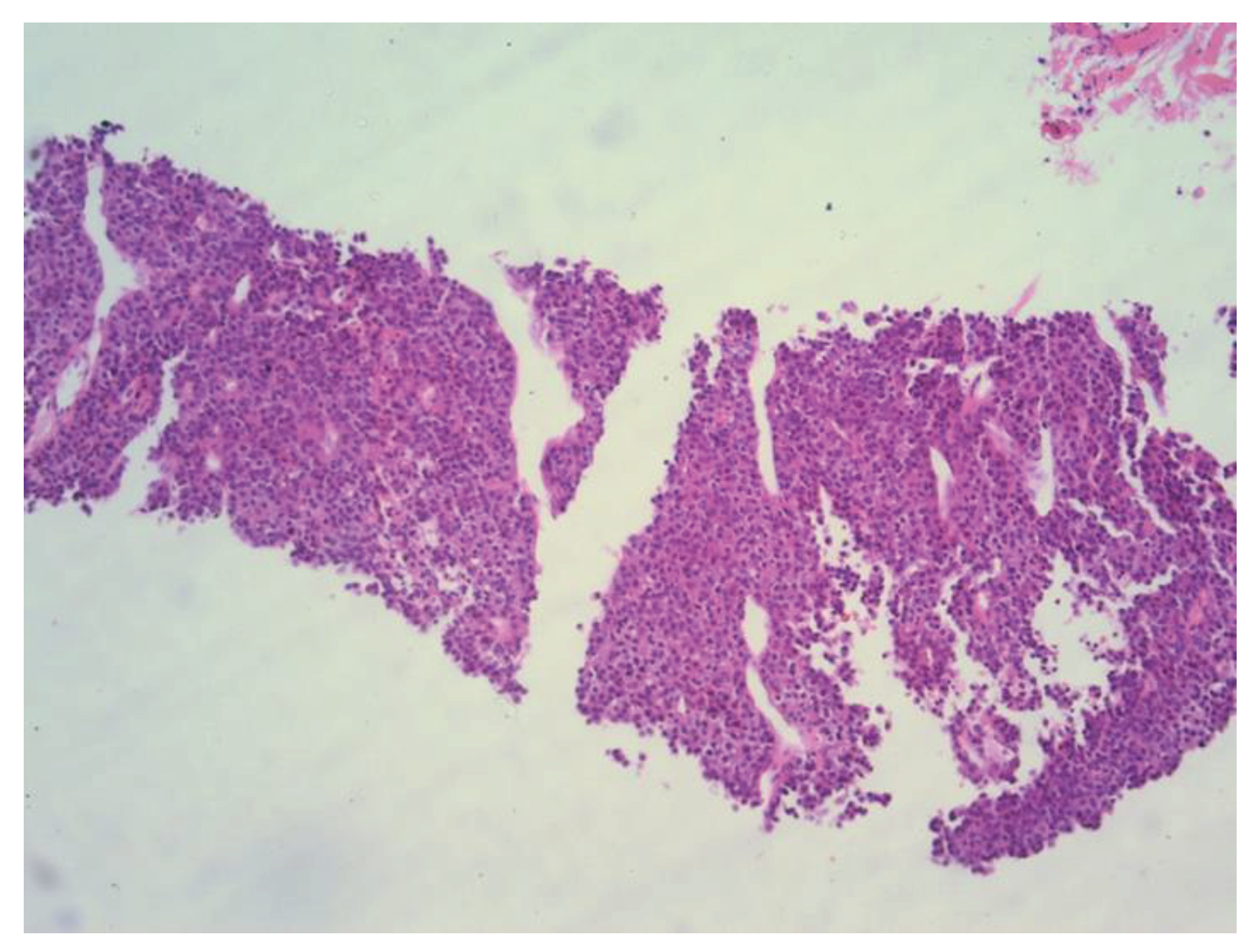

The patient was referred to the Department of Interventional Radiology in consideration of a percutaneous biopsy of the mass. The core biopsy was performed (

Figure 3), and PH findings indicated a metastatic carcinoma in the left mandible, completely consistent with previously diagnosed trabecular type of hepatocellular carcinoma (

Figure 4). There were no other sites of disease dissemination upon an endocranial, neck, chest, abdominal and pelvic CT performed shortly after. The maxillofacial oncological team concluded that due to the prolonged recovery from COVID 19 disease, as well as due to the accelerated disease progression and poor prognosis of the patients with extrahepatic disease, the surgical treatment of mandible lesion was not indicated and the treatment was continued with symptomatic and palliative treatment. Ten months later the patient died due to hepatic decompensation and local spread of the metastatic disease. However, there were no clinical or radiological signs of recurrent disease in the liver.

4. Discussion

Advances in imaging techniques and in the treatment of HCC patients with subsequent prolonged survival allow us to observe the extrahepatic metastases more frequently and earlier than we did before [

3]. The incidence of extrahepatic metastases is estimated to 13-36% [

6], with the most frequent sites being the lungs (18-55%), lymph nodes (26,7-53%), bones most commonly including axial sceleton (5,8-38%) and adrenals (8,4-15,4%) [

3], while mandibular metastasis is estimated to occur in 0,6% of cases [

7]. According to a literature review the mandible is an extremely rare site for HCC metastasis with around 70 cases reported from 1957, when it was first described [

8,

9].

HCC metastasizes hematogenously by tumor cell invasion of hepatic artery or portal venous branches, with subsequent seeding of the lungs as the most common site of metastatic disease. Therefore, the oral metastases are mostly associated with lung metastases, probably occuring by the same hematogenous route [

10]. Nevertheless, an isolated metastases in the orofacial region, as it occurred in the presented patient, require another explanation of the spread of the disease. In these cases, Batson’s valveless venous vertebral plexus was suggested as an alternative route of hematogenous disease spread. This plexus with various anastomoses allows the tumor cells to bypass the caval veins and reach vertebral and even bones of head and neck before reaching the right heart and the lungs. This route of metastatic disease was first suggested by Batson in 1940, who explained this vertebral venous plexus as the route for the “aberrant” or “paradoxical” metastases of the prostate or breast cancers by performing a series of experiments on cadavers [

11]. This is the most probable explanation for the vertebral metastases which are, as opposed to the orofacial, quite common.

Commonly reported clinical findings in patients with a mandibular metastasis of an HCC are those of a diffuse, firm and painless swelling in the temporal region [

12], that was consistent in our patient. Additionally, symptoms including difficulty in opening of the mouth, numbness of the surrounding regions, as well as toothache are observed [

4,

7,

8,

13,

14]. Since there have been various reports of initial presentation of a metastatic HCC with a solitary orofacial metastasis [

13,

14], even more commonly than after an HCC diagnosis is established [

7,

14,

15], we emphasize the need to consider this possibility in patients with known risk factors for HCC (liver cirrhosis, viral hepatitis and others). However, metastatic disease represents ~1% of all malignancies of the oral area [

4].

Typically, the radiologic presentation of HCC bone metastasis is an osteolytic soft-tissue mass, commonly hypervascular as the primary HCC itself [

16]. In that respect it is understandable why the lesion itself is prone to bleeding [

15,

17]. Due to the afore mentioned bone metastasis of HCC characteristics, special care needs to be taken while performing biopsy, therefore, percutaneous core biopsy or fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies are favorable compared to incisional biopsies [

7]. This characteristic imaging presentation of bone HCC metastasis was consistent in the presented patient, as evidenced by CT performed in the investigation of a painless jaw swelling. The neck CT demonstrated a large, infiltrative, hypervascular, osteolytic lesion in the left mandible ramus. Subsequently, percutaneous core biopsy of the left jaw mass, as well as PH report proved it to be the HCC metastasis in the left mandibular bone.

Considering the general conditions of these patients, their liver disease, the proneness to bleeding of these mandibular lesions, as well as their infiltrative nature, it is challenging to undertake radical procedures and complete resection, therefore the probability of complete removal of both the primary and metastatic lesions is low [

7,

18]. In such cases, the only reasonable approach is a palliative treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or different combinations [

7,

18]. Radiotherapy was considered in the presented patients however abandoned due to the size of the lesion.

5. Conclusions

Despite that HCC rarely metastasizes to the orofacial region, these metastases are more commonly presented as the initial symptoms of the disease, before even the primary tumor has been diagnosed. This possibility should be considered in any patient with a recent swelling in the orofacial and sinonasal area, especially when there is a history of a liver disease or other well-known risk factor for HCC development. Biopsy is indispensable in these cases and should not be delayed based solely on clinical grounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., A.I., K.M., A.F. and D.G.; methodology, D.M. , K.M. and A.I.; investigation, D.M., A.I., K.M., A.F.; resources, D.M., K.M., A.F. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., A.I., K.M., and D.B.; writing—review and editing, D.M.; M.Z. and D.B.; visualization, A.I. and K.M.; supervision, D.M., A.F. and D.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external founding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained the patient involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.fv.

References

- Sung H.; Ferlay J.; Siegel R.L.; Laversanne M.;, Soerjomataram I.; Jemal A.; Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 5, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Tang A.; Hallouch O.; Chernyak V.; Kamaya A.; Sirlin C.B. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: target population for surveillance and diagnosis Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018, 1, 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Natsuizaka M.; Omura T.; Akaike T.; Kuwata Y.; Yamazaki K.; Sato T.; Karino Y.; Toyota J.; Suga T.; Asaka M. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005, 11, 1781-7. [CrossRef]

- Cho J. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma in the maxilla and temporal bone: a rare case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 6, 224-228. [CrossRef]

- Huang H.H.; Chang P.H.; Fang T.J. Sinonasal metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007, 7-8, 238-41. [CrossRef]

- Schütte K.; Schinner R.; Fabritius M.P.; Möller M.; Kuhl C.; Iezzi R.; Öcal O.; Pech M.; Peynircioglu B.; Seidensticker M.; Sharma R.; Palmer D.; Bronowicki J.P.; Reimer P.; Malfertheiner P.; Ricke J. Impact of Extrahepatic Metastases on Overall Survival in Patients with Advanced Liver Dominant Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Subanalysis of the SORAMIC Trial. Liver Cancer. 2020, 12, 771-786. [CrossRef]

- Park J.; Yoon S.M. Radiotherapy for mandibular metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: a single institutional experience. Radiat Oncol J. 2019 12, 286-292. [CrossRef]

- Dick A.; Mead S.G.; Mensh M.; Schatten W.E. Primary hepatoma with metastasis to the mandible. Am J Surg. 1957, 12, 846-50. [CrossRef]

- Yu S.; Estess A.; Harris W.; Dillon J. A rare occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the mandible: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 201, 5, 1219-2. [CrossRef]

- Radzi A.B.; Tan S.S. A case report of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma in the mandible and coracoid process: A rare presentation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018, 1, e8884. [CrossRef]

- Batson O.V. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940, 7, 138-49. [CrossRef]

- Liu H.; Xu Q.; Lin F.; Ma J. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the mandibular ramus: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019, 3, 1047-105.

- Du C.; Feng Y.; Li N.; Wang K.; Wang S.; Gao Z. Mandibular metastasis as an initial manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma: A report of two cases. Oncol Lett. 2015, 3, 1213-1216. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ferreira R.; Savage-Leyva R.; Durán-Guerrero L.F.; Carranza-Sevilla M.D.R.;, Zamorano-Vazquez C.; Monroy-Godínez C.F.; Hernández-Ramírez G.R.; Torres-Zazueta J.M.; Ceron-Ibarra E.; Dorantes-Heredia R. Mandibular Metastasis as the First Manifestation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Case Report. Case Rep Oncol. 2023, 2, 88-95. [CrossRef]

- Pires F.R.; Sagarra R.; Corrêa M.E.; Pereira C.M.; Vargas P.A.; Lopes M.A. Oral metastasis of a hepatocellular carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004, 3, 359-68. [CrossRef]

- He J.; Zeng Z.C.; Tang Z.Y.;, Fan J.; Zhou J.; Zeng M.S.; Wang J.H.; Sun J.; Chen B.; Yang P.; Pan B.S. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma receiving external beam radiotherapy. Cancer. 2009, 6, 2710-20. [CrossRef]

- Huang S.F.; Wu R.C.; Chang J.T.; Chan S.C.; Liao C.T.; Chen I.H.; Yeh C.N. Intractable bleeding from solitary mandibular metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 9, 4526-8. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura Y.; Matsuda S.; Naitoh S. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the mandibular ramus and condyle: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997, 3, 297-306. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).