1. Introduction

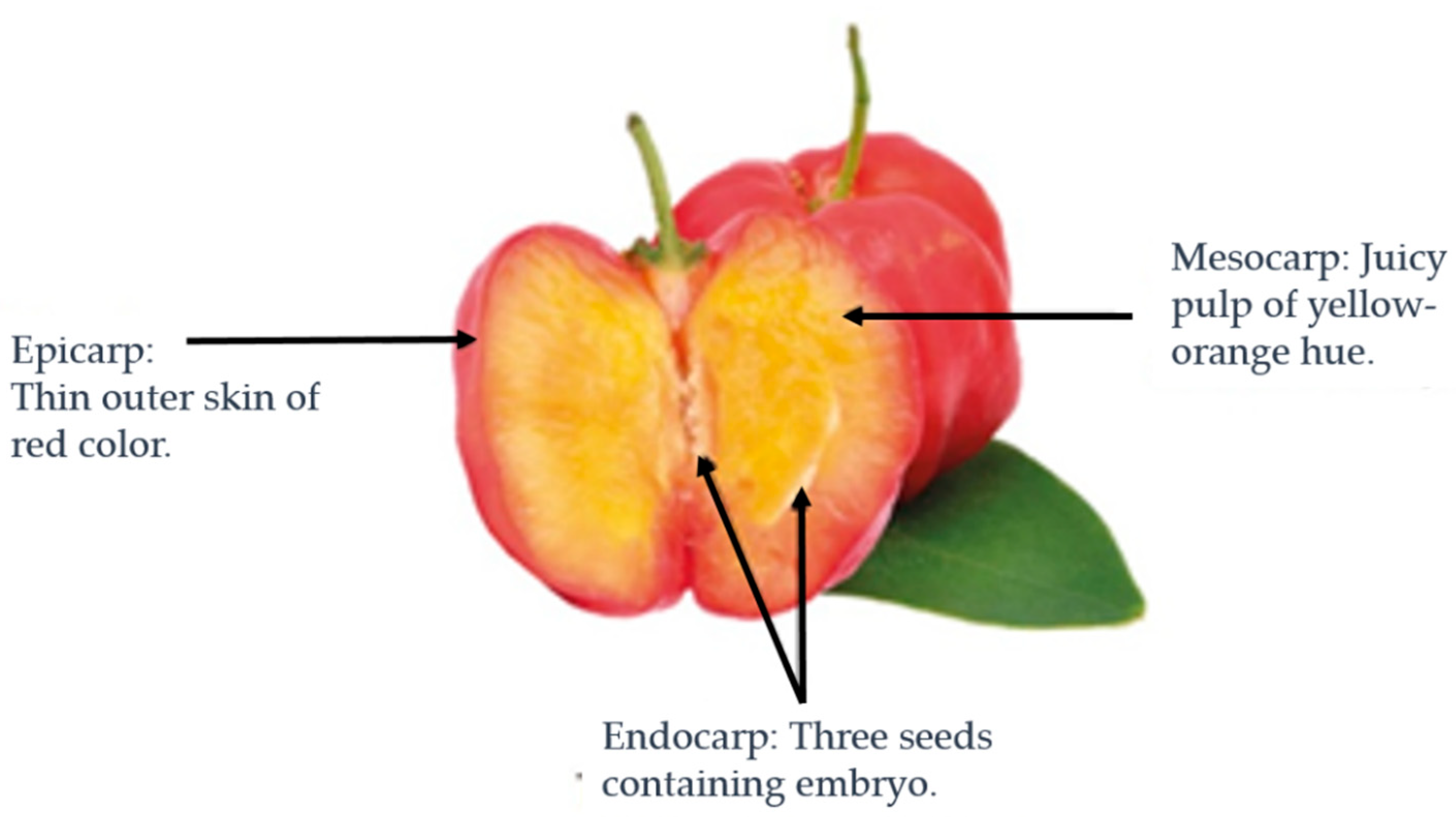

The acerola (

Malpighia punicifolia) (

Figure 1) is an exotic tropical fruit that resembles the cherry. It is a member of the Malpighia genus within the Malpighiaceae family, comprising 45 species of shrubs or small trees. These plants are predominantly indigenous to the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas [

1,

2]. Known for its rich nutrient profile, acerola contains antioxidant compounds, such as vitamins, carotenoids, and polyphenols [

3,

4]. This elevated concentration of antioxidants, especially vitamin C, positions acerola as an economically significant commodity. It finds extensive applications in the food industry, primarily in producing natural preservatives and nutraceutical products. These attributes underscore the fruit's health benefits and enhance its market value and the potential for diverse applications of its bioactive compounds [

5,

6,

7].

As early as 1946, researchers Asenjo and Guzmán identified acerola's exceptional ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content, thereby pioneering scientific interest in its potential health benefits [

8]. This seminal work catalyzed subsequent studies and has cemented the fruit's reputation for its unique compositional attributes and functional significance. In recent decades, Brazil has established itself as the global leader in acerola production, with an estimated annual yield of 61,000 metric tons [

9,

10]. This dominant position has enabled Brazil to control a significant share of the international market for acerola-based products, which range from frozen fruit and juice to jams, frozen concentrates, and liqueurs. Moreover, the cultivation of acerola has been expanding to other parts of the Americas and even Europe, largely to produce ascorbic acid supplements and specialized fruit juices [

4,

11,

12].

The large-scale production of acerola raises environmental concerns, especially concerning waste management. By-products such as seeds, grains, and pulp constitute approximately 40% of the fruit's total volume [

13]. Although these by-products pose potential environmental risks if improperly managed, they also offer untapped opportunities for sustainable development. These residues can be harnessed to produce a range of valuable products, including natural preservatives and dietary supplements, as they are often rich in phenolic compounds and other bioactive substances, sometimes even more so than the edible portions of the fruit [

14,

15].

Emerging studies are starting to examine the potential of acerola in various health-related applications beyond its antioxidant capabilities. For instance, acerola extract has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, suggesting a role in natural medicine and the potential for developing novel pharmaceuticals [

16]. Further research is warranted to explore these bioactive properties in greater depth, including clinical trials that might confirm the translational value of these findings.

Additionally, the fruit has been recognized for its potential in cosmetic applications. With its rich phytonutrient profile, acerola is currently being studied for its anti-aging effects on the skin. Preliminary investigations indicate that its bioactive compounds may protect against UV radiation damage and improve skin hydration, opening new avenues for the cosmetics industry to explore [

17]. Focusing on product development in this sector could add another layer to the fruit's economic significance and further diversify its applications.

While acerola's high ascorbic acid content is well-documented, the fruit also serves as a rich source of other phytonutrients, including carotenoids, phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins [

18,

19]. These phytonutrients endow the fruit with various biofunctional and therapeutic properties that are yet to be comprehensively explored. To fill this gap in our understanding and to potentially broaden the fruit's applications, this review aims to provide an in-depth analysis of the current state of acerola research. It will focus on its compositional attributes, pharmacological properties, and additional value-added uses, thereby helping to pinpoint current challenges and opportunities for its more extensive and economically viable industrial applications.

2. Chemical composition of acerola wastes

Acerola (

Malpighia punicifolia) is a reservoir of multiple macro and micronutrients, encompassing glucose, fructose, sucrose, and various organic acids [

20]. The fruit's physicochemical attributes and nutritional valuation are contingent upon various factors, including geographical origin, environmental conditions, agronomic practices, maturation stage, and post-harvest processing and storage [

21,

22]. The subsequent sections delineate the fruit's composition more exhaustively.

Carbohydrates: Byproducts of acerola are notably rich in carbohydrates, including glucose, fructose, sucrose, and starch as the predominant constituents [

23,

24]. These carbohydrates hold promise for utilization as energy sources or raw materials for producing biofuels and biopolymers [

11].

Organic Acids: Acerola fruit is renowned for its elevated concentrations of organic acids, a feature also found in its byproducts. Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) is the most abundant organic acid, followed by malic, citric, and tartaric acids [

23,

24]. These acids have prospective applications in the food and pharmaceutical sectors, serving as natural preservatives, flavor augmenters, and pH modulators [

25].

Polyphenols: Acerola byproducts offer a potentially rich source of polyphenols known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functionalities [

26]. This category includes anthocyanins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Anthocyanins, water-soluble pigments responsible for the red, blue, and purple hues in fruits, exhibit potential for application as natural colorants and therapeutic agents [

27,

28]. Flavonoids and phenolic acids also present various health benefits, such as protecting against cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [

26].

Carotenoids: Additionally, acerola byproducts are affluent in carotenoids, which confer various health benefits, including shielding against oxidative impairment and minimizing the risk of chronic diseases [

29]. Beta-carotene predominates as the most abundant carotenoid, trailed by lutein and zeaxanthin. Carotenoids are propitious for applications as natural colorants, food additives, and in the formulation of functional foods and dietary supplements [

30].

Fatty Acids: Acerola by-products also contain essential fatty acids like linoleic and oleic acids. These fatty acids are important in cellular function and inflammation modulation for human health. Moreover, these fatty acids could find applications in the cosmetics industry as moisturizing agents [

31].

Pectins: The byproducts also encompass pectins, a class of soluble dietary fibers widely utilized in the food industry as thickening and gelling agents [

32]. Pectins have been ascribed with cholesterol-lowering and prebiotic effects, making them pertinent for developing functional foods and dietary supplements [

33,

34].

The generation of acerola byproducts could contribute to environmental concerns if not managed efficiently. However, the high nutrient content in these byproducts indicates a missed opportunity for resource recovery. Thus, eco-friendly strategies for recycling these byproducts into valuable products are under investigation. The multifaceted chemical composition of acerola byproducts has garnered interest in novel applications. Current research explores their utility in formulating nutraceuticals, skin-care products, and natural dyes in the textile industry [

11].

The diverse chemical constituents of acerola byproducts make them a promising resource for many applications across different industries. Sustainable management strategies and innovative approaches could further elevate their value and utility.

3. Characterization of acerola wastes

The chemical composition of acerola waste is not uniform and can exhibit considerable variability. This variability is influenced by several factors, including but not limited to the maturity stage of the fruit, the processing methodology employed, and the geographical location of cultivation. These factors can result in significant differences in the waste's macronutrients, micronutrients, and bioactive compounds.

Table 1 shows the composition of acerola in 100 g of fresh weight. Acerola is an important source of several macro and micronutrients, such as ascorbic acid. It is one of the most important water-soluble vitamins, essential for collagen, carnitine, and neurotransmitter biosynthesis [

11].

Table 2 shows pulped acerola residues' physical, chemical, and total antioxidant activity [

35].

4. Applications

Due to its composition, the acerola fruit exhibits a set of well-documented properties like antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-hyperglycemic, antitumor, antigenotoxic, and hepatoprotective activity [

1,

22,

36], anti-mutagenic, anti-microbial, anti-obesity [

37], anti-fungal, and free radical scavenging activity [

38]. These bioactive properties have stimulated acerola consumption as fresh fruit or processed products [

4]. For these characteristics, acerola has a great agro-industrial potential in markets that demand products rich in nutrients, which at the same time improve health and prevent degenerative diseases [

21,

39], proving this is a large amount of research published about acerola in the food industry.

Furthermore, this fruit has been widely analyzed regarding its phytochemical and physicochemical composition. Some authors, such as [

11], offer a comprehensive literature analysis focusing on the compositional characteristics of the fruit and the biofunctional properties of the present phytonutrients. Chang et al. (2018) and others studied the phytochemical compositions, antioxidant efficacies, and potential health benefits of acerola, among other fruits [

40,

6]. Belwal et al. (2018) reviewed the scientific research on bioactive chemical constituents and the health-beneficial effects of acerola extracts and isolated compounds [

1].

In addition to the fruit, waste by-products and other plant parts have been analyzed for their composition and properties. To mention some examples, Alves et al. (2020) studied the phytochemical and bromatological composition of acerola bagasse flour, which is rich in fiber and antioxidant compounds [

41]. Silva et al. (2020) investigated bioactive compounds' content and extraction techniques from acerola waste, determining their potential in food and pharmaceutical applications [

42]. Da Silva et al. (2020) studied the constituents in acerola leaves; this study proposes a phytochemical, nutritional, and immunostimulatory analysis of aqueous extracts [

42]. Barros et al. (2019) also analyzed the leaves to determine the phytochemical composition of the saline extract from leaves and show the biological activities promoted by this extract [

43]. Vasavilbazo et al. (2018) analyzed the leaves and barks of acerola to determine its phenolic composition, carotenoid content, and antioxidant activity [

37].

However, many published articles were focused on evaluating a specific biological activity, or if a more general investigation is developed, this topic needs to be addressed. This review aims to detail all the reported physical activities associated with acerola fruits, leaves, seeds, peel, and residual by-products, highlighting its possible uses in the biomedical industry.

4.1. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity

Antioxidant activity is one of the widest studied properties in acerola; it is proven that its phytochemicals and compounds represent a powerful source of natural antioxidants, which are health-promoting and disease-preventing activities [

1,

21]. The wide range of phytochemicals present in acerola contributes significantly to its high antioxidant capacity. This activity depends on the synergistic action of the constituents of these different fractions [

44]. Due to the great interest in the antioxidant activity in acerola, the measurement of its capacity was performed by DPPH•, ABTS·+, FRAP, and ORAC assays, and multiple analyses were performed in different matrices;

Table 3 shows some assays applied to other parts of acerola showing promising results on antioxidant capacity tests.

4.2. Anti-inflammatory Activity

Inflammation is a physiological response that triggers a defense mechanism against various stimuli or conditions. The inflammatory response is induced by a sequential release of inflammatory mediators and the recruitment of leukocytes to the inflammation site; once they arrive, they are activated, triggering the release of more mediators, creating a network of connection between the tissue and the cells of the immune system, thus giving the inflammatory response [

50]. The phytochemicals present have been shown to reduce inflammation and related diseases through several points of cellular inflammatory pathways [

51]. Some studies suggest that some metabolites in acerola are related to the modulation of pathways involved in regulating the inflammatory mechanism, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) p38, ERK ½, and JNK [

52]. Different groups have investigated anti-inflammatory effects by performing in vitro assays using LPS-stimulated RAW-264.7 macrophage cell lines. Cabral et al. (2020) studied the anti-inflammatory properties of a blend powder formulation of 80% acerola and 20% green tea extract; their results suggest that co-treatment with blends could modulate the redox parameters in cells during the vitro inflammatory response [

52]. Moreover, the co-treatment with blends modulated inflammatory response by altering the secretion of cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α, causing, as a consequence, an anti-inflammatory effect. Albuquerque et al. (2019) studied 4 different fruit by-products, including acerola (peel and seeds), to evaluate the anti-inflammatory properties of water extracts prepared with this biomass; the results showed that the aqueous extract of acerola does not present NO-reducing activity in the LPS stimulated macrophages experiment [

53]. However, the extract in the presence of fruit fibers promotes the adhesion of beneficial probiotics to the intestinal walls, maintaining a balanced oxidative state in the intestinal environment, thus protecting the epithelium against inflammatory processes. Pereira et al. (2020) studied the anti-inflammatory activity using freeze-dried acerola extracts. Their results show that by evaluating selected inflammation-associated mRNA markers, a 50 ug/mL acerola extract can inhibit the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, and COX-2 genes associated with the in vitro inflammatory process [

54]. A different approach was developed by Milanez et al. (2014); these authors carried out an in vivo study using male Swiss albino mice and food treatments supplemented with commercial acerola juice. After 13 weeks, the histological analysis showed that acerola juice restores metabolic and inflammatory pathways to an average level [

55].

4.3. Anti-hyperglycemic Activity

Hyperglycemia is a condition like type 2 diabetes, characterized by an abnormal postprandial increase of blood glucose level caused by regularly consuming rapidly digestible carbohydrates [

56]. An important therapeutic approach to the treatment of type 2 diabetes is to decrease postprandial hyperglycemia by slowing glucose absorption through inhibition of the enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase in the digestive tract [

56]. Polyphenols have shown some beneficial effects in the prevention and management of diabetes through the inhibition of glucose absorption, inhibition of digestive enzymes, regulation of intestinal microbiota, modification of the inflammation response, and inhibition of the formation of advanced glycation end products [

57]. Barbalho et al. (2011) studied the effects of acerola juice intake on the glycemic and lipid profile of diabetic and non-diabetic Wistar rat offspring [

58]. The biochemical profile determination of blood samples taken from acerola extract-treated rats indicates a significant reduction in glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and increased HDL-c, promising a potential strategy for preventing diabetes and other diseases. Hanamura et al. (2005) performed research to characterize polyphenols from acerola fruits, identifying as a result of 3 different polyphenols (C3R, P3R, and quercitrin) for the first time [

59]. This study proved that three isolated, purified polyphenols and a crude extract of mixed polyphenols have an inhibitory effect on the α-amylase enzyme [

59]. Hanamura et al. (2006) studied the antihyperglycemic effect of a natural ethanol polyphenol fraction, evaluating the impact on the glucose intake of Caco-2 cells. They demonstrate that this extract decreased the glucose uptake level dose-dependently by adding the acerola polyphenol fraction. In this study, the researchers also performed an essay on ICR male mice, analyzing glucose and maltose intake; the results showed that the crude acerola extracts significantly suppressed the plasma glucose level after administering both glucose and maltose, suggesting that this extract had a preventive effect on hyperglycemia in the postprandial state [

60].

4.4. Antitumor Activity

Epidemiological research suggests that a polyphenol-rich diet protects against tumors, inhibiting proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and reducing drug resistance in gastric cancer cells [

61]. The role of phytochemicals has been associated with the modulation of different signaling cascades of the cell division process, which in turn is related to the induction of apoptosis, suppression of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and subsequent metastatic behavior of cancer cells. In addition, studies suggest that different phytochemicals increase the sensitivity of cancer stem cells to chemotherapy drugs [

62]. Motohashi et al. (2004) studied organic solvent extractions of acerola using two human oral tumor cell lines (oral squamous cell carcinoma cells (HSC-2) and submandibular gland carcinoma cells (HSG) and normal oral cells as control; their results suggest that some of the hexane fractions inhibited Pgp function in multidrug-resistant cancer cells more effectively than the control verapamil, highlighting the tumor-specific cytotoxic potential of acerola extract [

63]. Nagamine et al. (2002) studied the capacity of an acerola extract to control cell proliferation and the activation of the Ras signal pathway in the promotion stage of lung tumorigenesis in mice. They injected the mice with 4-(methyl nitrosamine)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), a potent carcinogen, and then fed the mice with acerola extract; the results showed that the pretreatment with acerola inhibited the increase in the levels of proliferating nuclear cell antigen and ornithine decarboxylase at the promotion stage and regulates abnormal cell growth at the promotion stage of lung tumorigenesis in mice [

64]. Ribeiro et al. (2015) demonstrated that some anthocyanins such as cyanidin 3-glucoside and cyanidin 3-rutinoside, lutein, α-carotene and β-carotene present in acai fruit extracts attenuate chemically induced mouse colon carcinogenesis by increasing total GSH and attenuating DNA damage and preneoplastic lesion development; is remarkable to mention that these compounds have been widely identified in acerola [

1,

4,

18,

65].

4.5. Antigenotoxic Activity

Metal ions generate DNA damage directly or indirectly by producing reactive oxygen species; these compounds are closely related to some diseases since some free radicals in an oxidative stress condition are not neutralized by antioxidant compounds or antioxidant cell protective mechanisms [

66]. In their research, Nunes et al. (2016) demonstrated that comparing bone marrow samples from mice groups treated with FeSO4 against groups, in turn, pretreated with acerola juice, it is proven that the juice exerted anti-mutagenic activity by significantly decreasing the mean values of micronuclei in the bone marrow [

66]. Da Silva et al. (2011) studied the antigenotoxic effect of acerola pulp extracts from ripe and unripe fruits. They applied a comet essay in CF-1 male mice blood to establish the protective ability of fruit extracts against the oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide; the results suggest that unripe fruit presented higher DNA protection than ripe fruit extract due to a high content of vitamin C in unripe fruits [

67]. In a similar study, Dimer et al. (2013) analyzed the anti-genotoxic capacity of acerola juice from fruits at different stages of ripening [

68]. Subjecting male mice to a diet high in sugars and fat induced glucose intolerance and DNA damage in the specimens. After 13 weeks, the diet was supplemented with acerola juice, resulting in a partial reversal of the DNA damage in the blood, kidney, liver, and bone marrow caused by the diet. Anti-genotoxic properties of acerola may be affected by genetic diversity as well as environmental factors [

68]. Differences in anti-genotoxic activity exist among acerola varieties grown in different regions of Brazil. Extracts of acerola pulp were evaluated in a comet assay on mouse blood cells in vitro, demonstrating some significant differences in DNA protection against H2O2 damage between two different plantations [

68], as well as between fruits of the same acerola species, same ripening stage, and harvest time, from two different plantations [

69].

4.6. Hepatoprotective Activity

Reactive nitrogen and oxygen species are produced during metabolic reactions and exert many important functions in cellular defense mechanisms; however, these components are overpowered in pathological situations, which can generate adverse effects [

70]. As mentioned, antioxidants play a protective role by inhibiting free radical-induced reactions and reducing oxidative damage, preventing the peroxidative deterioration of the cell membrane lipids and DNA damage [

71]. Nagamine et al. (2004) studied the hepatoprotective effect of dry extract powders of fruit purees and grind leaves of acerola [

72]. Researchers applied different extract powders in a physiological salt solution after the intoxication induced by D-Galactosamine in male Wistar rats. As a result, the components of the extracts diminished the hepatic inflammatory response, decreased hepatocellular injury, and improved liver function in rats under GalN intoxication [

72]. El-Hawary et al. (2021) evaluated a dried ethanol powdered acerola leaf extract on rats induced with hepatic damage by CCL4. Their results showed that all the tested doses showed a higher reduction in serum levels of TNF-α [

73]. However, the dose of 800 mg/Kg showed the highest hepatoprotective effect as it reduced the elevated serum levels of ALT, AST, NO, and TNF-α liver content, increasing the serum level of catalase. Marques et al. (2018) studied the protective potential of a lyophilized extract of acerola bagasse against CCL4-induced hepatoxicity in Wistar rats; their results showed that the treatments with this extract presented a decrease in the activity of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase, and an increase in superoxide dismutase, total antioxidant capacity, and albumin content [

70]. Gomes et al. (2013) investigated the effects of ripe acerola juice in vivo using female Swiss mice. The animals were pretreated with acerola juice for 15 consecutive days and then subjected to ethanol-induced stress, evaluating serum enzymes and the degree of lipid peroxidation. Compared to the ethanol-only treated group, the liver of acerola juice-fed animals before acute ethanol administration showed a significant reduction of lipid peroxidation, similar to control levels, proving that acerola juice can prevent hepatic damage [

71].

4.7. Anti-mutagenic Effect

Antimutagenic compounds reduce the frequency of spontaneous or induced mutations; vitamin C, polyphenols, and carotenoids can reduce oxidative stress levels and quench free radicals reducing the damage and promoting the protection of DNA against oxidative damage, showing antioxidant and antimutagenic effects [

67,

68]. Some compounds, such as cyclophosphamide (CP) [

74], iodine-131 [

75], and hydrogen peroxide [

76], may result in undesirable side effects and cause cellular mutations in organisms. Acerola juice mixed with other fruits showed high antiproliferative and antimutagenic activities against alterations induced by cyclophosphamide, possibly attributed to its high content of bioactive compounds [

77]; acerola pulp juice showed potential as an antimutagenic by statistically reduced the percentages of chromosomal alterations induced by this compound [

74]. Research developed by Düsman et al. (2016) also demonstrated that the consumption of acerola showed antimutagenic effects against iodine131 in acute and sub-chronic treatments, mainly by acting in the capture of free radicals produced by radiation [

74]. Research developed by Almeida et al. (2014) also demonstrates the potential of acerola extracts to reduce 131-I-induced damage [

75]. Some in vitro performed in bone marrow cells of mice stated that acerola mixed with different fruits show antimutagenic activity at different concentrations [

77]; juices from ripe and unripe acerola showed a significant decrease in micronucleus in contrast with an animal group treated with FeSO4 [

66]. Using acerola juice as a food supplement can help decrease oxidative stress and protect or repair the damage to the DNA in obese animals [

68]. Spada et al. (2008) studied the antimutagenic effect of different tropical fruits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae; their results suggest that frozen fruit extracts exhibited Antimutagenic effects and CAT-like activity. CAT neutralizes hydrogen peroxide, avoiding hydroxyl radical formation and damage to the DNA [

76].

4.8. Anti-bacterial Activity

Secondary metabolites produced by plants have a defensive function when certain microorganisms, such as viruses, parasites, fungi, or bacteria, attack them. The compounds with antibacterial action are usually terpenoids, phenolic compounds, alkaloids, polypeptides, coumarins, and camphor [

78,

21,

39,

79]. The antimicrobial activity of different acerola extracts has been evaluated using methods such as agar diffusion assay, disc diffusion test, and minimal inhibitory concentration evaluation (MIC) assay. Motohashi et al. (2004) used different solvents to prepare extracts from frozen and fresh acerola fruits, showing relatively high activity against S. epidermidis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa [

63]. Montero et al. (2020) studied the antimicrobial properties of hexane extracts from pulp, barks, and seeds. Their results showed that pulp and seed extracts have the greatest activity against E. coli compared to all the other fruits tested. However, this inhibition was lower than the ampicillin control [

78]. The bark extracts showed a low inhibition against S. Typhimurium and C. albicans. Some research groups proposed alcoholic extractions of phenolic compounds from different parts of the plant and industrial by-products to prove their potential against common bacteria. An ethanol extract of acerola leaves showed the ability to mildly inhibit the growth of B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa when compared to an ampicillin control [

73], methanol extractions of acerola bagasse flour exhibited antimicrobial activity on L. monocytogenes, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. cholerasuis [

12]; besides, methanolic fractions of different phenolic compounds were evaluated, the results suggest that the flavonoid fraction showed moderate antimicrobial properties against S. aureus [

21,

39]. Some research has focused on evaluating the potential of hydroalcoholic extractions. A 30:70 v/v ratio of ethanol: water extract yields strong antimicrobial activity against B. thermophacta, P. fluorescent, and P. fragi, and moderate activity against P. Putida [

80], and 1:1 solutions of ethanol: water showed moderate activity over P. aeruginosa and L. monocytogenes [

81]. A different approach to evaluate antibacterial properties was proposed by Pinheiro et al. (2020), in which the development of nanoparticles from acerola waste products was shown to possess antimicrobial properties against E. coli [

82].

4.9. Anti-obesity

Obesity is excessive fat accumulation in body tissues, influenced by genetics, energy-dense intake, high-fat foods, and the absence of physical activity [

83,

84]. Excessive body fat gain promotes inflammatory conditions associated with producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased production of reactive oxygen species, and decreased antioxidant defenses [

83]. Studies have shown the beneficial effects of antioxidant supplementation in the diet of obesity-related diseases [

85] and the consumption of phytochemicals, which can help to reduce body weight, decrease white adipose tissue, and regulate the appetite hormone [

83]. Milanez et al. (2014) studied the effect of unripe and ripe acerola juice on male Swiss mice fed with a cafeteria diet [

55]. Their results showed a reduction in weight gain, a reduction in (TAG) levels, and an increase in important anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TNF-α in adipose tissue. These results suggest that acerola juice reduces inflammation and diminishes obesity-associated defects in lipolytic processes. Vital et al. (2021) investigated the effects of acerola-derived products in the diet of male Wistar rats [

83]. Treatment with acerola did not alter weight gain, energy efficiency, and body weight. In addition, it was shown to increase antioxidant activity and reduce adiposity, showing a novel alternative to treating obesity. The role of antioxidant activity is reinforced by research such as that of Dimer et al. (2017), showing that acerola juice can reduce oxidative stress caused by obesity on energy metabolism enzymes [

85]. Marques et al. (2016) evaluated acerola bagasse flour methanol extracts to investigate the effects of -amylase and -glycosidase enzymes. Due to the content of phenolic compounds, the methanol extract inhibited these enzymes on in vitro assays; these results suggest that this extract may represent a good source of inhibitors and can be used as an auxiliary in the treatment of obesity [

84].

4.10. Anti-fungal Activity

Antifungal activity has been evaluated using the same techniques applied in antimicrobial assays. Motohashi et al. (2004) proved butanol and methanol extracts of acerola against yeast C. albicans and C. glabrata; their results showed a high inhibitory zone in contrast with X and X as positive controls [

63]. Different studies evaluate the effects of acerola leaf extracts against different fungal species. Schmourlo et al. (2007) studied an aqueous extract, proving that this extract has antibacterial effects over T. rubrum through MIC and agar diffusion assay [

79]. Besides, Barros et al. (2019) tested aqueous saline extracts from dry leaves on different species of Candida. The saline extract proved effective by inhibiting 90% of C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis but ineffective against C. glabrata [

43]. El-Hawary et al. (2022) studied the potential of ethanol extracts, showing a low response over C. albicans in contrast with the inhibition zone caused by the antibiotic amphotericin B [

73].

5. Conclusions

Acerola is an economically important tropical fruit known for its high concentration of antioxidants like vitamin C. Its versatile applications range from natural preservatives to nutraceutical products, positioning it as a valuable commodity in the food industry. Brazil has established itself as the global leader in acerola production, with the production scale expanding even to other parts of the Americas and Europe, mostly for producing ascorbic acid supplements and specialized fruit juices.

The large-scale production of acerola generates significant waste, including seeds, grains, and pulp, which constitute about 40% of the fruit's total volume. If not properly managed, these by-products could pose potential environmental risks. However, these waste products also represent an untapped opportunity for sustainable development. They are rich in phenolic compounds and other bioactive substances, sometimes even more than the edible portions of the fruit. This suggests they could be harnessed to produce valuable products, such as natural preservatives and dietary supplements.

Emerging research explores acerola's health benefits beyond its antioxidant capabilities, including its anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects. This indicates its potential role in natural medicine and the possibility of developing novel pharmaceuticals. Preliminary studies have suggested that acerola has potential anti-aging effects on the skin and can protect against UV radiation damage. This could open new avenues in cosmetic applications, further diversifying its economic significance. Besides ascorbic acid, acerola is a rich source of other phytonutrients like carotenoids, phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins. These compounds endow the fruit with various biofunctional and therapeutic properties that are yet to be comprehensively explored.

The paper underscores the need for more research to explore the diverse applications of acerola, including its waste products. It points to the challenges and opportunities in utilizing acerola waste as a sustainable source of raw materials and energy. The review aims to bridge the gaps in our understanding of acerola's compositional attributes, pharmacological properties, and additional value-added uses. It provides a valuable resource for future research to realize the fruit's full economic and therapeutic potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.V. and D.B.; investigation, J.V.; Y.C.; D.B; M.L.; M.C; A.M.; N.L.; J.Z.; L.C.H., writing—original draft preparation, J.V.; D.B. writing—review and editing, J.V.; D.B.; supervision, J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Belwal, T.; Prasad, H.; Hassan, H.; Ahluwalia, S.; Fawzy, M.; Mocan, A.; Atanasov, A. Phytopharmacology of acerola (Malpighia spp.) and its potential as functional food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 74(1), 99-106.

- De Assis, S.; Fernandes, P.; Martins, A.; Faria, O. Acerola: importance, culture conditions, production, and biochemical aspects. Fruits 2008, 63(1), 93-101.

- Farinelli, D.; Portarena, S.; Da Silva, D. F.; Traini, C.; Da Silva, G. M.; Da Silva, E. C.; Da Veiga, J. F.; Pollegioni, P.; Villa, F. Variability of Fruit Quality among 103 Acerola (Malpighia emarginata D.C.) Phenotypes from the Subtropical Region of Brazil. Agriculture, 2021, 11(11), 1078.

- Carneiro, I.; Pereira, V.; Claudio, J.; de França, F.; Tonetto, S.; & dos Santos, M. Brazilian varieties of acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) produced under tropical semi-arid conditions: Bioactive phenolic compounds, sugars, organic acids, and antioxidant capacity. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45(8), 1-12.

- Silva, P.: Mendes, L.; Rehder, A.; Duarte, C.; Barrozo, M. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from acerola waste. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57(12), 4627-4636. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, V., Borges, J., Chagas, E., Yoshida, C., Vanin, F., Laurindo, J., & Carvalho, R. Production and Characterization of Dehydrated Acerola Pulp: A Comparative Study of Freeze and Refractance Window Drying. Food Sci. Eng. 2022, 4(1), 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Ellong, E.; Billard, C.; Adenet, S.; Rochefort, K. Polyphenols, Carotenoids, Vitamin C Content in Tropical Fruits and Vegetables and Impact of Processing Methods. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 299-313. [CrossRef]

- Asenjo, C.F.; Freire De Guzmán, A.R. The high ascorbic acid content of the West Indian cherry. Science 1946; 103 (2669), 219.

- Leonarski, E.; Guimarães, A. C.; Cesca, K.; Poletto, P. Production process and characteristics of kombucha fermented from alternative raw materials. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101841. [CrossRef]

- IBGE. 2017. Produção de Acerola. https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/producao-agropecuaria/acerola/br.

- Prakash, A.; Baskaran, R. Acerola, an untapped functional superfruit: A review on latest frontiers. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55(9), 3373-3384. [CrossRef]

- Rezende, T.; Caetano, A.; Avelar, L.; Simão, A.; Andrade, G.; Duarte, A. Characterization of phenolic compounds, antioxidant, and antibacterial potential the extract of acerola bagasse flour. Acta Sci. Technol. 2017, 39(2), 143-148.

- Duzzioni, A. G.; Lenton, V. M.; S. Silva, D. I.; S. Barrozo, M. A. Effect of drying kinetics on main bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of acerola (Malpighia emarginata D.C.) residue. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48(5), 1041-1047.

- Bortolotti, C. T.; Santos, K. G.; Francisquetti, M. C.; Duarte, C. R.; Barrozo, M. A. Hydrodynamic study of a mixture of West Indian Cherry Residue and Soybean Grains in a spouted bed. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 91(11), 1871-1880. [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Da Silva, M.; Da Silva, R.; Ritcher, M.; Falcao, A.; Da Silva, J. A influência da origem geografica de amostras de acerola (Malpighia glabra L.) em relação ao seu potencial genotóxico e antigenotóxico. Rev. Inic. Cient. ULBRA 2008, 7(1), 37-45.

- Souza NC, de Oliveira Nascimento EN, de Oliveira IB, Oliveira HML, Santos EGP, Moreira Cavalcanti Mata MER, Gelain DP, Moreira JCF, Dalmolin RJS, de Bittencourt Pasquali MA. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of blend formulated with compounds of Malpighia emarginata D.C (acerola) and Camellia sinensis L. (green tea) in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110277.

- Zerbinati, N.; Sommatis, S.; Maccario, C.; Di Francesco, S.; Capillo, M.C.; Rauso, R.; Herrera, M.; Bencini, P.L.; Guida, S.; Mocchi.; R. The Anti-Ageing and Whitening Potential of a Cosmetic Serum Containing 3-O-ethyl-l-ascorbic Acid. Life (Basel). 2021, 11(5), 406.

- Mezadri, T.; Villaño, D.; Fernández, M.; García, M.; Troncoso, A. Antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity in acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) fruits and derivatives. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21(4), 282-290. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; Belorio, M.; Gómez, M. Assessing Acerola Powder as Substitute for Ascorbic Acid as a Bread Improver. Foods 2022, 11(9), 1366. [CrossRef]

- Righetto, A.M.; Netto, F.M., Carraro, F. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Juices from Mature and Immature Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC). Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2005, 11(4), 315-321. [CrossRef]

- Delva, L.; Goodrich, R. Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC): Production, Postharvest Handling, Nutrition, and Biological Activity. Food Rev. Int., 2013a, 29(2), 107–126.

- Hoang, Q. B.; Pham, N.T.; Le, T.T.; Duong, T.N.D. Bioactive compounds and strategy processing for acerola: A review. CTU J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 14(2), 46-60. [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Pintado, M.; Oliveira, A.L.S. Natural Bioactive Compounds from Food Waste: Toxicity and Safety Concerns. Foods 2021, 10, 1564. [CrossRef]

- Hrelia, S.; Angeloni, C.; Barbalace, M. C. Agri-Food Wastes as Natural Source of Bioactive Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2023, 12 (2), 351. [CrossRef]

- Teshome, E.; Forsido, S. F.; Vasantha Rupasinghe, H. P.; Keyata, E. O. Potentials of Natural Preservatives to Enhance Food Safety and Shelf Life: A Review. Sci. World J. 2021, 2022, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.S.M.; Alves, R.E.; de Brito, E.S.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F.; Mancini-Filho, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities of 18 non-traditional tropical fruits from Brazil. Food Chem. 2010, 121(4), 996-1002. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Nunes, A.R.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Dietary Effects of Anthocyanins in Human Health: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14(7), 690. [CrossRef]

- Câmara, J.S.; Locatelli, M.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Oliveira, H.; Arlorio, M.; Fernandes, I.; Perestrelo, R.; Freitas, V.; Bordiga, M. Behind the Scenes of Anthocyanins—From the Health Benefits to Potential Applications in Food, Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Fields. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5133.

- Saini, R. K.; Nile, S. H.; Park, S. W. Carotenoids from fruits and vegetables: Chemistry, analysis, occurrence, bioavailability and biological activities. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 735–750. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A. J.; Mandić, A. I.; Bantis, F.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G. I. A.; Brnčić, M.; Bysted, A.; Cano, M. P.; Dias, M. G.; Elgersma, A.; Fikselová, M.; García-Alonso, J.; Giuffrida, D.; Gonçalves, V. S. S.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Kljak, K.; Lavelli, V.; Manganaris, G. A.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Marounek, M.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Periago-Castón, M. J.; Pintea, A.; Sheehan, J. J.; Šaponjac, V. T.; Valšíková-Frey, M.; Van Meulebroek, L.; O’Brien, N. A Comprehensive Review on Carotenoids in Foods and Feeds: Status Quo, Applications, Patents, and Research Needs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62 (8), 1999-2049.

- Batista, K. S.; Soares, N. L.; Dorand, V. A. M.; Alves, A. F.; Dos Santos Lima, M.; de Alencar Pereira, R.; Leite de Souza, E.; Magnani, M.; Persuhn, D. C.; de Souza Aquino, J. Acerola Fruit By-Product Alleviates Lipid, Glucose, and Inflammatory Changes in the Enterohepatic Axis of Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134322. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Espinoza, C.; Carvajal-Millán, E.; Balandrán-Quintana, R.; López-Franco, Y.; Rascón-Chu, A. Pectin and Pectin-Based Composite Materials: Beyond Food Texture. Molecules 2018, 23 (4), 942.

- Gullón, B.; Gómez, B.; Martínez-Sabajanes, M.; Yáñez, R.; Parajó, J.; Alonso, J. Pectic oligosaccharides: Manufacture and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30 (2), 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Niu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y. Emerging trends in functional pectin processing and its fortification for synbiotics: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 80-97. [CrossRef]

- Carmo, J.; Nazareno, L.; Rufino, M. Characterization of the Acerola Industrial Residues and Prospection of Their Potential Application as Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Source. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 236–241. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Andrade, J.; Rajan, M.; Narain, N. Influence of the Phytochemical Profile on the Peel, Seed and Pulp of Margarida, Breda and Geada Varieties of Avocado (Persea Americana Mill) Associated with Their Antioxidant Potential. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e25822. [CrossRef]

- Vasavilbazo, A.; Almaraz, N.; González, H.; Ávila, J.; González, A.; Delgado, E.; Torres, R. Caracterización Fitoquímica y Propiedades Antioxidantes de la Acerola Silvestre Malpighia umbellata Rose. CyTA J. Food 2018, 16 (1), 698-706.

- El-Hawary, S.; El-Fitiany, R.; Mousa, O.; Salama, A.; Gedaily, R. Metabolic Profiling and In Vivo Hepatoprotective Activity of Malpighia glabra L. Leaves. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45 (2), 1-16.

- Delva, L.; Goodrich, R. Antioxidant Activity and Antimicrobial Properties of Phenolic Extracts from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) Fruit. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48 (1), 1048–1056.

- Chang, S.; Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F. Superfruits: Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Efficacies, and Health Effects – A Comprehensive Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 59 (10), 1–26.

- Alves, S.; Macedo, M.; Maia, F.; Fernandes, R.; da Silva, K. Preparation, Phytochemical, and Bromatological Evaluation of Flour Obtained from the Acerola (Malpighia punicifolia) Agroindustrial Residue with Potential Use as a Fiber Source. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 134, 1–7.

- Da Silva, B.; Dias, D.; Cavalcante, D.; da Costa, F.; Nunes, A.; da Cruz, I.; de Oliveira, M.; Lagos, C. Phytochemical Analysis, Nutritional Profile and Immunostimulatory Activity of Aqueous Extract from Malpighia emarginata DC Leaves. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23(1), 1–8.

- Barros, B.; Barboza, B.; Ramos, B.; de Moura, M.; Coelho, L.; Napoleao, T.; Correia, T.; Paiva, P.; da Cruz, I.; Da Silva, T.; Lima, C.; de Melo, C. Saline Extract from Malpighia emarginata DC Leaves Showed Higher Polyphenol Presence, Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity and Promoted Cell Proliferation in Mice Splenocytes. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Mezadri, T.; Pérez, A.; Hornero, D. Carotenoid Pigments in Acerola Fruits (Malpighia emarginata DC.) and Derived Products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 220(1), 63–69.

- Guedes, T.; Rajan, M.; Barbosa, P.; Silva, E.; Machado, T.; Narain, N. Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Different Varieties viz. Flor Branca, Costa Rica and Junco of Green Unripe Acerola (Malphigia emarginata D.C.) Fruits. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Dala, B.; Pereira, T.; de Souza, L.; Andrade, R.; de Oliveira, J.; Carbonera, N. Domestic Processing and Storage on the Physical-Chemical Characteristics of Acerola Juice (Malpighia glabra L.). Sci. Agrotechnol. 2019, 43(1), 1–8.

- Stafussa, A. P.; Maciel, G. M.; Rampazzo, V.; Bona, E.; Makara, C.; Demczuk, B.; Isidoro Haminiuk, C. W. Bioactive Compounds of 44 Traditional and Exotic Brazilian Fruit Pulps: Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21(1), 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, C.; Brito, K.; Nayara, F.; da Cruz, E.; dos Santos, M.; Bordin, V.; Fernandes, E.; Gómez, A.; Leite, E.; Gomes, M. Protective Effects of Tropical Fruit Processing Coproducts on Probiotic Lactobacillus Strains During Freeze-Drying and Storage. Microorganisms 2020, 8(1), 1–15.

- Duarte, S.; Mesquita, C.; Da Silva, G.; dos Santos, M.; Bordin, V.; Fernandes, E.; Leite, E.; Gomes, M. Improvement in Physicochemical Characteristics, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Acerola (Malpighia emarginata D.C.) and Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Fruit By-products Fermented with Potentially Probiotic Lactobacilli. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 134(1), 1–9.

- Hanada, T.; Yoshimura, A. Regulation of Cytokine Signaling and Inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002, 13(4), 413–421. [CrossRef]

- Bellik, Y.; Boukraâ, L.; Alzahari, H.; Bakhotmah, B.; Abdellah, F.; Hammoudi, S.; Iguer, M. Molecular Mechanism Underlying Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Allergic Activities of Phytochemicals: An Update. Molecules 2012, 18(1), 322–353. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, N.; de Oliveira, E.; Bezerra, I.; Lisboa, H.; Paiva, E.; Rangel, E.; Pens, D.; Fonseca, J.; Siqueira, R.; de Bittencourt. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Blend Formulated with Compounds of Malpighia emarginata D.C (Acerola) and Camellia sinensis L. (Green Tea) in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128(1), 1–9.

- Albuquerque, M.; Levit, R.; Beres, C.; Bedani, R.; de Moreno, A.; Isay, S.; Leblanc, J. Tropical Fruit By-Products Water Extracts of Tropical Fruit By-Products as Sources of Soluble Fibers and Phenolic Compounds with Potential Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Functional Properties. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 52(1), 724–733.

- Pereira, F.; Xiong, J.; Borges, K.; Targino, R.; Esposito, D. Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory Activities, and Wound Healing Properties of Freeze-Dried Fruits. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2020, 4(1), 1–9.

- Milanez, F.; Dimer, D.; Daumann, F.; de Oliveira, S.; Luciano, T.; Correa, J.; Alves, A.; Neves, R.; Rosa, J.; Missae, L.; Rodrigues, B.; Moraes, V.; de Souza, C.; Santos, F. Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Juice Intake Protects Against Alterations to Proteins Involved in Inflammatory and Lipolysis Pathways in the Adipose Tissue of Obese Mice Fed a Cafeteria Diet. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13(1), 13–24.

- Asgar, A. The Anti-Diabetic Potential of Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16(1), 91–103. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhao, C.; Capanoglu, E.; Paoli, P.; Simal, J.; Mohanram, K.; Wang, S.; Buleu, F.; Pah, A.; Turi, V.; Damian, G.; Dragan, S.; Tomas, M.; Khan, W.; Wang, M.; Delmas, D.; Puy, M.; Dar, P.; Chen, L.; Xiao, J. Dietary Polyphenols as Antidiabetic Agents: Advances and Opportunities. Food Front. 2020, 1(1), 18–44. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.; Damasceno, D.; Machado, A.; Palhares, M.; Aparecida, K.; Oshiiwa, M.; Sazaki, V.; Sellis, V. Evaluation of Glycemic and Lipid Profile of Offspring of Diabetic Wistar Rats Treated with Malpighia emarginata Juice. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 10(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hanamura, T.; Hagiwara, T.; Kawagishi, H. Structural and Functional Characterization of Polyphenols Isolated from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Fruit. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69(2), 280–286. [CrossRef]

- Hanamura, T.; Mayama, C.; Aoki, H.; Hirayama, Y.; Shimizu, M. Antihyperglycemic Effect of Polyphenols from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Fruit. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70(8), 1813–1820. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, M.; Shu, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Polyphenol Mechanisms Against Gastric Cancer and Their Interactions with Gut Microbiota: A Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29(8), 5247–5261. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, T.; Bhattacharya, R. Phytochemicals modulate cancer aggressiveness: a review depicting the anticancer efficacy of dietary polyphenols and their combinations. J. Cell. Physio. 2020, 235(11), 7696–7708. [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, N.; Wakabayashi, H.; Kurihara, T.; Fukushima, H.; Yamada, T.; Kawase, M.; Sohara, Y.; Tani, S.; Shirataki, Y.; Sakagami, H.; Satoh, K.; Nakashima, H.; Molnár, A.; Spengler, G.; Gyémánt, N.; Ugocsai, K.; Molnár, J. Biological Activity of Barbados Cherry (Acerola Fruits, Fruit of Malpighia emarginata DC) Extracts and Fractions. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18(3), 212–223.

- Nagamine, I.; Akiyama, T.; Kainuma, M.; Kumagai, H.; Satoh, H.; Yamada, K.; Yano, T.; Sakurai, H. Effect of Acerola Cherry Extract on Cell Proliferation and Activation of Ras Signal Pathway at the Promotion Stage of Lung Tumorigenesis in Mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2002, 48 (1), 69–72. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.; Franco, M.; Galhardo, R.; Pessanha, M.; Henrique, A.; Barbisan, L. Protective Effects of Spray-Dried Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart) Fruit Pulp against Initiation Step of Colon Carcinogenesis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77 (3), 432–440.

- Nunes, R.; Silva, V.; da Silva, M.; Silva, M.; Maglione, C.; Moraes, V.; Falcão, A.; Da Silva, J. Protective Effects of Acerola Juice on Genotoxicity Induced by Iron in Vivo. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39 (1), 122–128.

- Da Silva, R.; Silva, V.; Da Silva, M.; Richter, M.; Costa, L.; Rocha, A.; Abin, J.; Martínez, M.; Ferronato, S.; Falcão, A.; Da Silva, J. Antigenotoxicity and Antioxidant Activity of Acerola Fruit (Malpighia glabra L.) at Two Stages of Ripeness. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2011, 66 (2), 129–135.

- Dimer, D.; Da Silva, J.; Daumann, F.; Formentin, A.; Longaretti, L.; Paganini, A.; de Lira, F.; Campos, F.; Falcão, A.; Silva, D.; Moraes, V. Corrective Effects of Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Juice Intake on Biochemical and Genotoxic Parameters in Mice Fed on a High-Fat Diet. Mutat. Res., Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2013, 770 (1), 144–152.

- Da Silva, R.; Silva, V.; Da Silva, M.; Ritcher, M.; Abin, J.; Martínez, M.; Falcão, A.; Da Silva, J. Genotoxic and Antigenotoxic Activity of Acerola (Malpighia glabra L.) Extract in Relation to the Geographic Origin. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27 (10), 1495–1501.

- Marques, T.; Caetano, A.; Cesar, P.; Braga, M.; Machado, G.; de Sousa, R.; Correa, A. Antioxidant Activity and Hepatoprotective Potential of Lyophilized Extract of Acerola Bagasse against CCl4-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Wistar Rats. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42 (6), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, N.; Mota, E.; Sousa, D.; Freitas, C.; de Oliveira, M.; Marinho, A.; Alcântara, M.; Fernandes, D. Effect of the Pretreatment with Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Juice on Ethanol-Induced Oxidative Stress in Mice e Hepatoprotective Potential of Acerola Juice. Free Radic. Antioxid. 2013, 3 (2), 16–21.

- Nagamine, I.; Fujita, M.; Hongo, I.; Nguyen, H.; Miyahara, M.; Parkányiová, J.; Pokorný, J.; Dostálová, J.; Sakurai, H. Hepatoprotective Effects of Acerola Cherry Extract Powder against D-Galactosamine-Induced Liver Injury in Rats and its Bioactive Compounds. Czech J. Food Sci. 2004, 22 (1), 159–162. [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, S.; Mousa, O.; Ahmed, R.; El Gedaily, R. Cytotoxic, Antimicrobial Activities, and Phytochemical Investigation of Three Peach Cultivars and Acerola Leaves. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 9 (2), 221–234.

- Düsman, E.; Almeida, L.; Tnin, L.; Vicentini, V. In vivo antimutagenic effects of the Barbados cherry fruit (Malpighia glabra Linnaeus) in a chromosomal aberration assay. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15 (4), 1–9.

- Almeida, I.; Düsman, E.; Heck, M.; Pamphile, J.; Lopes, N.; Tonin, L.; Vicentini, V. Cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of iodine-131 and radioprotection of acerola (Malpighia glabra L.) and beta-carotene in vitro. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12 (4), 6402–6413. [CrossRef]

- Spada, P.; Nunes, G.; Bortoloni, G.; Henriques, J.; Salvador, M. Antioxidant, Mutagenic, and Antimutagenic Activity of Frozen Fruits. J. Med. Food 2008, 11 (1), 144–151. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, L.; Dionísio, A.; da Silva, A.; Wurlitzer, N.; Sousa, E.; Anceski, G.; Montenegro, I.; Nogueira, M.; Hai, R. Antiproliferative, antimutagenic and antioxidant activities of a Brazilian tropical fruit juice. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59 (2), 1319–1324.

- Montero, I.; Alves, E.; Saravia, S.; Aparecida, J.; Santos, R.; de Malo, A.; Carvalho, R.; Estevam, P.; Marcia, J.; Cardoso, P.; Goncalves. Antimicrobial activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition of oils and Amazon fruit extracts. J. Med. Plants Res. 2020, 14 (3), 88–97.

- Schmourlo, G.; de Morais, Z.; de Oliveira, D.; Costa, S.; Mendonça, R.; Alviano, C.; Miranda, A. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Edible Plants and Their Potential Use as Nutraceuticals. Acta Hort. 2007, 756 (1), 355–368. [CrossRef]

- Tremonte, P.; Sorrentino, E.; Succi, M.; Tipaldi, L.; Panella, G.; Ibañez, E.; Mendiola, J.; Di Renzo, T.; reale, A.; Coppola, R. Antimicrobial Effect of Malpighia Punicifolia and Extension of Water Buffalo Steak Shelf-Life. J. Food Sci. 2015, 81 (1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.; Gúllon, P.; Fátima, M.; Carvalho, A.; Domingues, V.; Gomes, A.; Becker, H.; Longhinotti, E.; Deleure, C. Brazilian fruit pulps as functional foods and additives: Evaluation of bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 172 2015, (1), 462–468. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.; Linhares, A.; Silva, A.; Moraes, L.; Machado, P.; Wilane, R. Bioactive potential of nanoparticles of acerola byproduct (Malpighia spp.): Bioaccessibility in nectar. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9 (9), 1–22.

- Vital, A.; Alencar, M.; Alves, K.; de Freitas, P.; Silveira, N.; Alves, L.; Chaves, S.; Gonçalves, S.; de Souza, J.; Leite, E.; Cunha, A. Effects of consumption of acerola, cashew and guava by-products on adiposity and redox homeostasis of adipose tissue in obese rats. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 43 (1), 283–289.

- Marques, T.; Caetano, A.; Simão, A.; Castro, F.; de Oliveira, V.; Corrêa, A. Methanolic extract of Malpighia emarginata bagasse: phenolic compounds and inhibitory potential on digestive enzymes. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26 (2), 191–196.

- Dimer, D.; Tezza, G.; Daumann, F.; Longaretti, L.; Dajori, A.; Mezari, L.; Carvalho, M.; Streck, E.; Moraes, V. Effects of acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) Juice Intake on Brain Energy Metabolism of Mice Fed a Cafeteria Diet. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54 (1), 954–963.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).