Submitted:

04 October 2023

Posted:

04 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

2.1. The Influence of Social Norms on Rural Households' Disposal of Pesticide Packaging Waste

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Regulation on the Relationship Between Social Norms and RHs' PPW Disposal Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

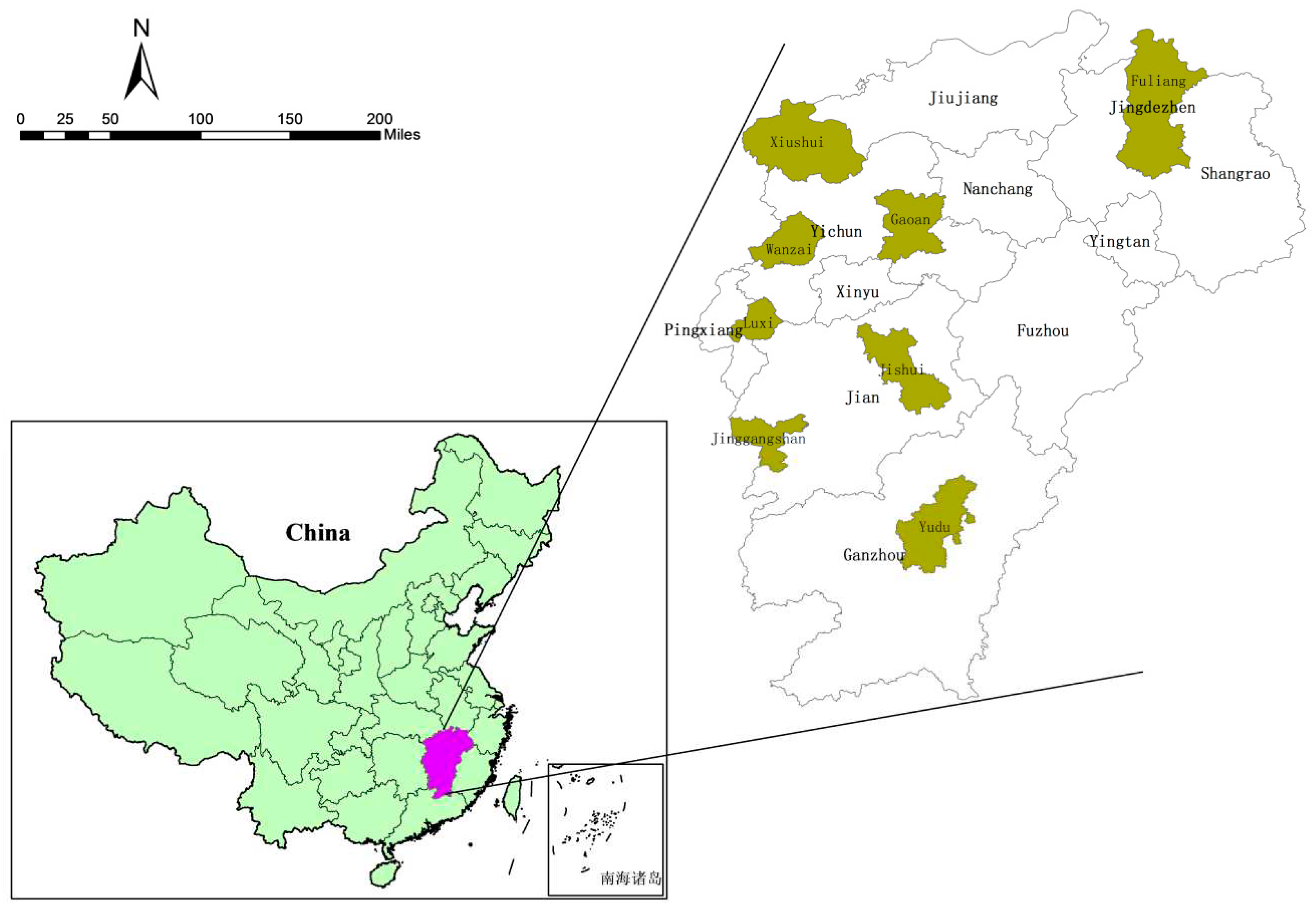

3.1. Source of Data Collection

3.2. Choice Experiment Method

3.2.1. Benchmark Regression

3.2.2. Examining Moderation Effects

3.3. Variable Selection

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Direct Influence of Social Norms on Pesticide Packaging Waste Disposal Behavior

4.2. Robustness Tests

4.3. Addressing endogeneity

4.4. Moderation effects test

5. Main Conclusion and Policy Implication

5.1. main conclusion

5.2. policy implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma A: Shukla A, Attri K, et al. Global trends in pesticides: A looming threat and viable alternatives. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 201, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. , Bluemling, B., Mol, A.P.J. Mitigating land pollution through pesticide packages - the case of a collection scheme in Rural China. Total Environ 2018, 622–623, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recena M C P, Caldas E D, Pires D X, et al. Pesticides exposure in Culturama, Brazil—knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Environmental research 2006, 102, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines on management options for empty pesticide containers. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/a99d7652-8322-4a28-92a2-726c92dd3bc4/ (accessed on 05 2008).

- Hu N, Zhang Q, Li C, et al. Policy intervention effect research on pesticide packaging waste recycling: evidence from Jiangsu, China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 922711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis D, Hiskakis M, Karasali H, et al. Design of a European agrochemical plastic packaging waste management scheme—Pilot implementation in Greece. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2014, 87, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zadjali S, Morse S, Chenoweth J, et al. Disposal of pesticide waste from agricultural production in the Al-Batinah region of Northern Oman. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 463, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadlinger N, Mmochi A J, Dobo S, et al. Pesticide use among smallholder rice farmers in Tanzania. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2011, 13, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondori A, Bagheri A, Allahyari M S, et al. Pesticide waste disposal among farmers of Moghan region of Iran: current trends and determinants of behavior. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2019, 191, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Barrera A, Pennings J M E, Hofenk D. Understanding producers' motives for adopting sustainable practices: the role of expected rewards, risk perception and risk tolerance. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2016, 43, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi K, Pirsaheb M, Maleki S, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of farmers about pesticide use, risks, and wastes; a cross-sectional study (Kermanshah, Iran). Science of the total environment 2018, 645, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondori A, Bagheri A, Sookhtanlou M, et al. Pesticide use in cereal production in Moghan Plain, Iran: Risk knowledge and farmers’ attitudes. Crop Prot 2018, 110, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Zhao X, Zhang D, et al. Associated factors of pesticide packaging waste recycling behavior based on the theory of planned behavior in Chinese fruit farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty M K, Behera B K, Jena S K, et al. Knowledge attitude and practice of pesticide use among agricultural workers in Puducherry, South India. Journal of forensic and legal medicine 2013, 20, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow M F A, Awadh D G, Albaho M S, et al. Pesticide knowledge and safety practices among farm workers in Kuwait: Results of a survey. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouma J, Bulte E, Van Soest D. Trust and cooperation: Social capital and community resource management. Journal of environmental economics and management 2008, 56, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyle R, E. Who will pay? Subsidies or taxes for recycling in the heartland. Resources, conservation and recycling 1993, 9, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Dong F, Chen M, et al. Advances in recycling and utilization of agricultural wastes in China: Based on environmental risk, crucial pathways, influencing factors, policy mechanism. Procedia environmental sciences 2016, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li B, Xu C, Zhu Z, et al. How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: Subsidies VS social norms. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 367, 133016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini R B, Reno R R, Kallgren C A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of personality and social psychology 1990, 58, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi W K, Huber J, Bell J. Promoting recycling: private values, social norms, and economic incentives. American Economic Review 2011, 101, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingjiao T A N, Xiaoting Y A N, Weilin F. The Mechanism and Empirical Study of Village Rules in Rural Revitalization and Ecological Governance. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 2019, 64, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty M K, Behera B K, Jena S K, et al. Knowledge attitude and practice of pesticide use among agricultural workers in Puducherry, South India. Journal of forensic and legal medicine 2013, 20, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eras J, Costa J, Vilarò F, et al. Prevalence of pesticides in postconsumer agrochemical polymeric packaging. Science of the total environment 2017, 580, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie L M, Galarraga I, Milford A B, et al. Using food taxes and subsidies to achieve emission reduction targets in Norway. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 134, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D. The design of policy instruments towards sustainable livestock production in China: an application of the choice experiment method. Sustainability 2016, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. , Zhou, Hong. Can social trust and policy of rewards and punishments promote farmers’ participation in the recycling of pesticide packaging waste? Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 2021, 35, 17–23. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini R B, Goldstein N J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei R, Safa L, Damalas C A, et al. Drivers of farmers' intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of environmental management 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman G, Albarracín D. Norm theory and the action-effect: The role of social norms in regret following action and inaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2017, 69, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch S, E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied 1956, 70, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri A, Bondori A, Allahyari M S, et al. Modeling farmers’ intention to use pesticides: An expanded version of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of environmental management 2019, 248, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu X, Zhang Z, Kuang Y, et al. Waste pesticide bottles disposal in rural China: Policy constraints and smallholder farmers’ behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 316, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li F N, Zhang J B. "Face" or "Benefit": The Impact of Reputational Incentives and Economic Incentives on the Participation of Migrant Farmers in Village Environmental Governance. Rural Economy 2021, 12, 90–98. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wąs A, Malak-Rawlikowska A, Zavalloni M, et al. In search of factors determining the participation of farmers in agri-environmental schemes–Does only money matter in Poland? Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li H, Lv L, Zuo J, et al. Dynamic reputation incentive mechanism for urban water environment treatment PPP projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2020, 146, 04020088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske J J, Kobrin K C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of environmental education 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant K, C. The interactional community: Emergent fields of collective agency. Sociological Inquiry 2012, 82, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse W, Steg L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Global environmental change 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąs A, Malak-Rawlikowska A, Zavalloni M, et al. In search of factors determining the participation of farmers in agri-environmental schemes–Does only money matter in Poland? Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable type | Variable Meaning and Assignment | Average value | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: | ||||

| Pesticide Packaging Waste Disposal Behavior | Pesticide Packaging Waste Littering Scale: 1 = Frequently Littered, 2 = Occasionally Littered, 3 = Never Littered. | 2.692 | 0.564 | |

| Core Explanatory Variable: | ||||

| Social Norms | Descriptive norms | Extent of Pesticide Packaging Litter in Village Fields: 1 = Very Serious, 2 = Serious, 3 = Average, 4 = Minor, 5 = Very Minor. | 4.268 | 0.914 |

| Directive norms | Social Blame for Abandoned Pesticide Packages: 0 = No, 1 = Yes. | 0.624 | 0.485 | |

| Moderating Variable: Environmental Regulation: | ||||

| Incentive regulation | Economic incentives | Are villagers given financial incentives for good participation? 0=No, 1=Yes | 0.301 | 0.459 |

| Reputational incentives | Financial Incentives for Villager Participation: 0 = No, 1 = Yes. | 0.443 | 0.497 | |

| Penalize regulation | Financial penalties | Financial Penalties for Villagers with Subpar Participation: 0 = No, 1 = Yes. | 0.252 | 0.435 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Characteristics of Household Heads | Age | Based on Empirical Survey Data (Years). | 53.716 | 14.402 |

| Education level | Educational Attainment Categories: 1 = Elementary School and Below, 2 = Junior High School, 3 = High School/Middle School/Technical School, 4 = University College, 5 = Bachelor's Degree and Above. | 1.774 | 0.929 | |

| Health | 1=very unhealthy, 2=unhealthy, 3=fair, 4=healthy, 5=very healthy | 3.659 | 0.981 | |

| Attributes of households | Business scale | Based on Empirical Survey Data (Hectares). | 0.341 | 1.037 |

| Part-time involvement | Non-farm labor force/labor force (%) | 0.154 | 0.279 | |

| Happiness | Happiness Rating Scale: 1 = Very Unhappy, 2 = Unhappy, 3 = Average, 4 = More Happy, 5 = Very Happy. | 4.218 | 0.860 | |

| Factors related to the village | The cultivated land area of the village group | Based on Empirical Survey Data (Hectares). | 84.661 | 73.857 |

| Cultivated land quality | Arable Land Fertility Assessment: 1 = Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Fair, 4 = Good, 5 = Very Good. | 3.812 | 0.848 | |

| Mountainous terrain (Plains reference) |

0 = No, 1 = Yes. | 0.366 | 0.482 | |

| Hilly terrain (Plains reference) |

0 = No, 1 = Yes. | 0.545 | 0.498 | |

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive norms | 0.435*** (0.101) |

0.296*** (0.113) |

| Directive norms | 0.781*** (0.196) |

0.766*** (0.205) |

| Age | -0.018** (0.009) |

|

| Education level | -0.139 (0.120) |

|

| Health | 0.251** (0.110) |

|

| Business scale | -0.248*** (0.078) |

|

| Part-time involvement | 0.118 (0.371) |

|

| Happiness | -0.363*** (0.129) |

|

| The cultivated land area of the village group | -0.004*** (0.001) |

|

| Cultivated land quality | 0.515*** (0.143) |

|

| Mountainous terrain (Plains reference) |

-0.093 (0.402) |

|

| Hilly terrain (Plains reference) |

-0.362 (0.355) |

|

| Prob> chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 0.042 | 0.103 |

| Obs | 574 | 574 |

| Variable | Model (3) Often littering |

Model (4) Occasional littering |

Model (5) Never littered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive norms | -0.014** (0.006) |

-0.035*** (0.013) |

0.049*** (0.018) |

| Directive norms | -0.036** (0.011) |

-0.090*** (0.023) |

0.126*** (0.033) |

| Age | 0.001** (0.0004) |

0.002** (0.001) |

-0.003** (0.001) |

| Education level | 0.007 (0.006) |

0.016 (0.014) |

-0.023 (0.020) |

| Health | -0.012** (0.005) |

-0.030** (0.013) |

0.041** (0.018) |

| Business scale | 0.012*** (0.004) |

0.029*** (0.009) |

-0.041*** (0.012) |

| Part-time involvement | -0.006 (0.018) |

-0.014 (0.044) |

0.020 (0.061) |

| Happiness | 0.017** (0.007) |

0.043*** (0.015) |

-0.060*** (0.021) |

| The cultivated land area of the village group | 0.0002** (0.0001) |

0.0004*** (0.0002) |

-0.0006*** (0.0002) |

| Cultivated land quality | -0.024*** (0.008) |

-0.061*** (0.016) |

0.085*** (0.023) |

| Mountainous terrain(Plains reference) | 0.004 (0.019) |

0.011 (0.047) |

-0.015 (0.066) |

| Hilly terrain(Plains reference) | 0.017 (0.017) |

0.043 (0.042) |

-0.060 (0.058) |

| Obs | 574 | 574 | 574 |

| Variable | Whether to litter pesticide packaging waste Model (6) |

Pesticide Packaging Waste Disposal Behavior Model (7) |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive norms | 0.276** (0.114) |

0.262* (0.150) |

| Directive norms | 0.716*** (0.209) |

0.827*** (0.274) |

| Age | -0.012 (0.009) |

0.019 (0.014) |

| Education level | -0.158 (0.125) |

-0.116 (0.150) |

| Health | 0.299*** (0.114) |

0.293** (0.146) |

| Business scale | -0.290*** (0.097) |

-0.291*** (0.087) |

| Part-time involvement | 0.189 (0.379) |

-0.328 (0.458) |

| Happiness | -0.330** (0.129) |

-0.477** (0.209) |

| The cultivated land area of the village group | -0.005*** (0.001) |

-0.004*** (0.002) |

| Cultivated land quality | 0.502*** (0.145) |

0.604*** (0.202) |

| Mountainous terrain (Plains reference) |

-0.113 (0.416) |

-0.202 (0.517) |

| Hilly terrain (Plains reference) |

-0.345 (0.368) |

-0.582 (0.438) |

| Prob> chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 0.122 | 0.144 |

| Obs | 574 | 574 |

| Variant | Model (8)Descriptive norms | Model (9)Directive norms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First phase | Second phase | First phase | Second phase | |

| Descriptive norms | 0.338* (0.189) |

|||

| Directive norms | 0.589** (0.288) |

|||

| Instrumental variable: | ||||

| Neighborly relations | 0.196*** (0.061) |

0.124*** (0.027) |

||

| Control Variables | Containment | Containment | ||

| Shea’s Partial R2 | 0.028 | 0.033 | ||

| Phase I F-value | 10.209 | 21.519 | ||

| Durbin (score) test p-value | 0.096 | 0.096 | ||

| Wu-Hausman test p-value | 0.099 | 0.099 | ||

| Obs | 574 | 574 | ||

| Incentive regulation | Penalize regulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic incentives | Reputational incentives | Financial penalties | ||||

| Model (10) | Model (11) | Model (12) | Model (13) | Model (14) | Model (15) | |

| Descriptive norms | 0.042** (0.020) |

0.032 (0.021) |

0.070*** (0.020) |

|||

| Directive norms | 0.128*** (0.036) |

0.074* (0.039) |

0.111*** (0.036) |

|||

| Economic incentives | 0.082 (0.198) |

0.128** (0.061) |

||||

| Reputational incentives | 0.021 (0.159) |

0.089* (0.051) |

||||

| Financial penalties | 0.447** (0.181) |

0.118* (0.069) |

||||

| Descriptive norms * Economic incentives | 0.009 (0.046) |

|||||

| Directive norms * Economic incentives | -0.014 (0.084) |

|||||

| Descriptive norms * Reputational incentives | 0.035 (0.038) |

|||||

| Directive norms * Reputational incentives | 0.137* (0.072) |

|||||

| Descriptive norms * Financial penalties | -0.079* (0.043) |

|||||

| Directive norms * Financial penalties | 0.019 (0.089) |

|||||

| Control Variables | Containment | Containment | Containment | Containment | Containment | Containment |

| Prob> chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| PseudoR2 | 0.115 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.103 | 0.119 | 0.115 |

| Obs | 574 | 574 | 574 | 574 | 574 | 574 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).