Introduction:

The present coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic changed the daily routine of millions of people worldwide. To prevent the spread of infection, different approaches were adopted across the globe. Among these measures was a lockdown, adopted by many countries to prevent the masses from this fatal infection [

1,

2]. In Saudi Arabia, the lockdown was also observed to prevent the spread of infection which restricted the people in their homes and prohibited them from going out into public places for any activity that was not necessary [

3]. In Saudi Arabia, the government adopted different alternatives to facilitate the public and one of them was “Teach and study from Home”. Right after the start of the pandemic, the Ministry of Education instructed educational institutions to deliver all their classes through online platforms. As a result, a significant number of students were studying online, which led to a more sedentary lifestyle [

3]. Every university did its best to adapt to the new situation, by keeping the regular classes with the same workload and encouraging students to utilize more self-directed learning methods [

4].

The lockdown likely made it more difficult to implement physical activity (PA), which has been linked to higher rates of musculoskeletal discomfort [

5]. According to one study, the level of discomfort increased in lockdown as compared to pre lock-down period in persons suffering from chronic pain. [

6]. Students used to sit for extended periods in their academic routines, frequently on unsuitable chairs, for learning purposes which leads to musculoskeletal problems [

1]. The students spent a long duration on their computers, laptops, or tablets. The use of these devices is also linked to different MSDs problems, including back, neck, and shoulder pain [

7,

8]. Mostly, using electronic devices, people adopt an improper posture that leads to discomfort and musculoskeletal changes, especially in the spine, and the upper extremities [

7]. Moreover, physical inactivity can also lead to changes in musculoskeletal problems and pain [

5]. Musculoskeletal pain can decline students’ academic achievement, quality of life, and later professional performance [

9].

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) include injuries to soft and hard tissues like bones, joints, tendons, nerves, and muscles. MSDs are related to the workplace, negatively impacting professionals’ quality of life [

8]. There are many theories related to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) that can happen in the workplace and affect teachers and students [

10]. These theories describe the pain and biomechanical damage resulting in musculoskeletal injuries [

11]. Such as multivariate interaction theory explains an alteration of the mechanical order of a biological system through psychosocial structure and skill of individual genetics. Differential fatigue theory explains the lack of equilibrium in occupational activity produces dyskinesia, resulting in the injury of the musculoskeletal system. Cumulative load theory accounts for the amount of load and repetition of movement during occupational tasks exerted on the musculoskeletal system. Overexertion Theory is about exceeding the tolerance limits of soft tissues resulting in occupational musculoskeletal injury [

11]. A study conducted in Hail, Saudi Arabia school teachers showed an increased risk of MSDs in female teachers more than males. Most of them reported musculoskeletal pain in one or more sites, and the commonest site was the back then the shoulder, and then the knee [

6].

There is a scarcity of empirical research specifically examining the impact of online education on musculoskeletal health among university students and faculty members during a COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the Saudi context. Educational institutions can use the study’s insights to improve the design of online courses, incorporating measures to reduce musculoskeletal strain and enhance the overall learning experience. The research can inform the development of policies and guidelines for online education that prioritize the well-being of students and faculty members, ensuring equitable access to education. Identifying risk factors allows for the development of targeted interventions, such as ergonomics training, physical activity promotion, or mental health support, to mitigate musculoskeletal health issues.

The primary aim of the present study was to examine the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among both university students and faculty members engaged in online education. Our secondary objective was to thoroughly assess the various contributing factors associated with the development of these musculoskeletal disorders.

Materials and Methods:

Study Design, Setting, and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among students and teachers of the University of Hail, Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted from January 2022 to March 2022. The registered course-based undergraduate students and faculty members at the University of Hail, who were actively engaged in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic Participants in the study were 18 years of age or older, and their inclusion was irrespective of their year of study or gender. Those with physical disabilities, rheumatic disease, suffered from MSDs before the start of online education, pregnant women, and people who had previous surgery on their limbs or spine were excluded.

Sampling and Sample Size

Study participants were selected by purposive sampling technique. The online Raosoft sample size calculator (Raosoft, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) with a confidence interval of 95% at 80% response rate with a marginal error of 5% was used to calculate the sample size. According to the student affairs department, the total number of preparatory year students and faculty members including both males and females was 2494 in 2021. Thus the required sample size was 157 for this study.

Outcome Measures

1. Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ)

The primary questionnaire employed in this study for investigating the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders was the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ). It’s important to note that the NMQ is a well-established and validated tool, having undergone validation processes in both Arabic and English languages in previous research [

12]. Within the context of our study, the NMQ was utilized to assess the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders across nine distinct anatomical regions of the body nine anatomical parts ( neck, upper and lower back, upper limb joints (shoulders, elbows, wrists/hands) and lower limb joints (knees, hips/thighs/buttocks, and ankle/feet) of the body. The utilization of the NMQ and the comprehensive examination of these nine anatomical parts allowed us to conduct a thorough assessment of the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among our study participants, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the impact of online education on their musculoskeletal health.

2. Predictors:

To construct the questionnaire, a thorough review of the existing literature was undertaken. This comprehensive exploration delved into various predictors, encompassing demographic factors, work-related characteristics, and lifestyle patterns. Finally, the study incorporated a range of parameters to comprehensively examine the experiences of participants involved in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. These parameters encompassed demographic information such as gender and age, with participants falling into the categories of male or female and varying age groups [

13]. Additionally, the study considered BMI as a relevant health indicator. Marital status was categorized as single or married, while smoking status was assessed as either “yes” or “no”[

14].

Physical activity levels were a pivotal component of our study, aligning with the guidelines established by the World Health Organization (WHO) for adults aged 18 to 65. Participants’ physical activity was categorized into four distinct levels: low (such as walking which needs low effort), moderate (such as jogging which needs moderate effort (150 min/week)), high High intensity (such as running which needs high effort (75 min/week)) , or no physical activity( Sedentary) [

15]. The study also investigated participants’ habits during online education sessions, including whether they took regular breaks to stand, stretch, or walk (“yes” or “no”) and their sitting posture “good” (neck and back straight while at work, using mobile phones and laptops) or “bad” during these sessions. Finally, the study recorded the average daily hours spent on online education, with options ranging from 2-4 hours, 5-6 hours, 7-8 hours, or above 8 hours [

6]. This comprehensive set of parameters aimed to provide a holistic understanding of the experiences and behaviors of the study’s participants during the pandemic [

6].

Ethical Considerations: Ethical approval was sought from the ethical committee of Hail University (H-2021-241). The survey respondents’ responses were kept anonymous, and the information gathered was kept private. The consent form was included online with the study explanation before starting the questionnaire.

Data Collection Procedure:

The data collection procedures for this study involved the utilization of an online questionnaire designed through Google Forms. The data collection process was distinct for students and faculty members and incorporated several steps to ensure thoroughness and maximize participation rates. For the student cohort, data collection commenced by visiting their classrooms, where the online questionnaire link was shared directly with them. Additionally, the link was disseminated through their class WhatsApp groups, accompanied by a request for immediate responses. This multi-channel approach aimed to reach students effectively and facilitate their prompt participation.

In the case of faculty members, a different strategy was employed. Individualized questionnaire links were sent directly to their email addresses and WhatsApp contacts. To enhance the response rate, constant reminders were periodically dispatched, reinforcing the importance of their input to the study. These meticulous data collection procedures were designed to optimize engagement from both students and faculty members, maintain transparency in the research process, and uphold ethical standards throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel sheet (version 16.33) was prepared from data collected through an online Google form. Analysis was done by SPSS version 27 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The frequencies and percentages were used to represent the MSD prevalence in the sample. Overall prevalence was calculated in any part of the body as well as multiple sites of the body based on the last 7 days and 12 months. A binominal regression test was done to assess the predictors (gender, physical activity level, posture, time spent online education per day) with highly prevalent anatomical sites (low back, neck, upper back, etc.). The association of different characteristics with total pain and disability in 12 months and the last 7 days was assessed by chi-square test. The statistical significance level was below 0.05.

Results

Participant’s Characteristics

In total, 175 study participants returned the questionnaire with 60 % (63% of students and 56 % of faculty members) response rate. The majority were females (80%) and young aged 26.9 ± 9.7 years, with an age range from 18 to 56 years. The average BMI was 39.23 ± 9.8 with most of the respondents being single (75.4 %), and only 8.6% were smokers. Students represented the largest proportion (75%) of the sample. Concerning online education sessions, 22.9 % of the participants responded that all their classes were online and 77.1% stated that part of their classes were online. About half (53.7%) of the participants spent 2-3 hours on online education. A good posture was practiced by only 32.6% while the rest had poor posture 67.4%. The characteristics of study participants as students and teachers can be observed in

Table 1.

The Overall Prevalence of MSDs

The overall prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in any part of the body was (90.3%) within the duration of the last 12 months. The prevalence of MSDs was higher in females than males (90.7 % vs. 88.6%). 70.9% of study participants reported MSDs in multiple anatomical parts. The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is depicted in

Table 2.

Disability in 12 months had a significant difference between males and females with X

2= 10.20 (3, n=175), 0.017, and among teachers X

2=13.35 (3, n=44) 0.004. Pain during the last 7 days had a significant difference between males and females 7.48 (3, n=175), .05, and among teachers X

2=8.94(3, n=44) .03. P values and prevalence are shown in

Table 2.

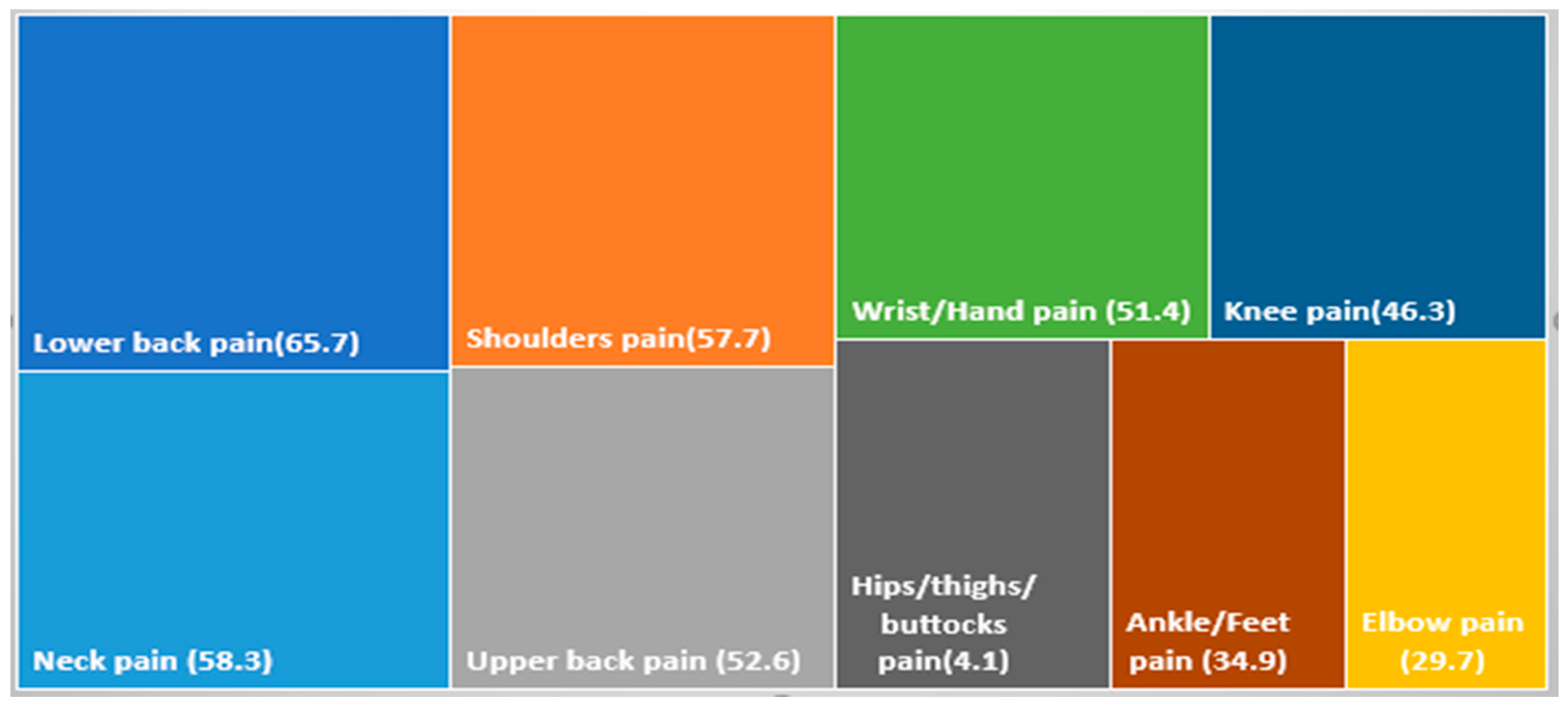

The Commonest Sites of MSDs:

The commonest anatomical site for MSDs was the low back (65.7%), the neck (58.3%), and shoulders (57.7%) while the least affected site was the elbow (29.7%). Pain in 12 months, prevalence percentage can be observed in (

Figure 1).

Binomial Logistic Regression for High-Occurrence Sites

The effects of gender, physical activity, posture, and spent time on e-devices on neck, shoulder, and upper and lower back pain were assessed by binomial logistic regression. The model explained 7.8% (Nagelkerke R

2) of variations in pain in the neck in 12 months and classified 58.3% of the cases correctly. Out of four variables, gender was significantly associated with neck pain in 12 months with “Odds ratio (OR): 2.7 (95% CI): 1.24–5.84; p = 0.012)” with Females having a 2.7-fold higher odds ratio than males (

Table 3). The model explained 5.8% (Nagelkerke R

2) of variations in pain in the shoulder in 12 months and classified 57.7% of the cases correctly. Shoulder pain was also significantly associated with posture “OR: 2.02 ((95% CI): 1.04-3.89; p = 0.03 )”. Bad posture has a two times higher odd ratio than good posture (

Table 4). The model explained 15.8% (Nagelkerke R

2) of variations in pain upper back in 12 months and classified 52.6% of the cases correctly. Pain in the Upper back was associated with posture “OR: 3.46 (95% CI): 1.73-6.93; p = 0.001”. Bad posture has a 3.5 times higher odd ratio than good posture and with gender “OR : 3.65 (95% CI): 3.65-1.59; p = 0.002)”. Females have a 3.6 times higher odd ratio than males(

Table 5). The model explained 5.4% (Nagelkerke R

2) of variations in pain in the lower back in 12 months and classified 65.7% of the cases correctly. Lower back pain was significantly associated with gender “OR: 2.24 (95% CI): 1.04-4.83; p = 0.03”. Females have a 2.2 times higher odd ratio than males (

Table 6).

Association of Pain and Disability with Age, Gender Posture, Physical Activity, and Duration of e-Device Use

The association of pain and disability in 12 months and pain in 7 days with age, gender, posture, physical activity, and exercise duration was also assessed with a chi-square test (

Table 5). Gender was significantly associated with total disability in 12 months X2 (3, N = 175) = 10.200, p = .01, specifically in teachers as well X2 (3, N = 44) = 13.345, p = .004 and pain during 7 days X2 (3, N = 175) = 7.481, p = .05, also with the more specific association in teachers X2 (3, N = 44) = 8.974, p = .03 while physical activity was associated with a disability X2 (3, N = 175) = 17.473, p = .042. Duration of use of the electronic device was also associated with disability X2 (9, N = 175) = 20.815, p = .013 and specifically in students X2 (9, N = 131) = 19.987, p = .018 and specifically in students X2 (9, N = 131) = 19.987, p = .018. Physical activity was also associated with disability X2 (9, N = 175) = 17.473, p = .042. (

Table 7).

Discussion:

The present study analyzed anatomical prevalence, and risk factors associated with MSDs in students and faculty members from Hail University Saudi Arabia during online classes. The current study also showed a positive association between MSDs and increased spent hours on e-devices, level of physical activity, posture, and gender.

Results showed that 90.3% of participants had MSDs and 93.1% of students suffered MSDs. A study conducted in Taiwan reported 86% prevalence which is comparable to the findings of the present study [

16]. However, some recent studies done in Mexico, China, and Turkey reported 69%, 60.3%, and 77% MSDs occurrence among students respectively [

9,

16,

17,

18]. Teaching at the university level is one of the highly demanding professions so teachers are usually more prone to MSDs (19). Our study reported that 93% of teachers suffered from MSDs in their back, neck, shoulders, and wrists more often, while Ng et al. reported that 80.1% of teachers had musculoskeletal problems (24). Occurrence of MSDs was higher in females i.e. 90% as compared to males and 88% in the current study, S¸Engul et al. also found that during COVID-19 females suffered more as compared to males from MSDs and pain [

19]. Different studies conducted previously showed females’ functional sufferings are high due to increased pain intensity and disability as compared to males. This can be explained based on different biological and biomechanical structures in females from males. There are more C and Aδ fibers in the muscles of females which are more responsive to distortions and also an inflammatory response to tissue damage is higher in females [

20,

21].

The present study reported higher prevalence in the lower back, neck, shoulder region, upper back, and wrist MSDs, and less in hips and ankles. Also, Akıncı et al. and Kurnaz Ay et al. found females have more loss of productivity and absence as they suffer from back, neck, and shoulder pain more as compared to females [

22,

23]. 80% of Indian undergraduates were suffering from MSDs symptoms in the head, neck, and eyes with 58 to 56 % in the dominant shoulder fingers, and hand during the online study (5). A study by Ng et al. also reported the most prevalent sites were the wrists, upper leg and arm, and lower leg while the spine and hip joints were least affected [

24]. During the pandemic, the duration of working hours in front of electronic devices for students and faculty members increased. Time in a static position (sitting) without preparing suitable workstations affects their back, shoulders, and neck more as compared to other anatomical sites. A study conducted in Turkey also reported more effects on the neck, shoulders, back, right forearm, and both wrists, but also on the hip during the post-online education period [

25]. Musculoskeletal pain was also found highly prevalent among teachers in Slovakia, the EU, Italy, Lithuania, Estonia, and Bulgaria, with the most involved body region, the spine [

26]. Also, 68.5% of high school teachers in Aljouf Saudi Arabia reported pain in the musculoskeletal system [

27]. Parjapti et al. also reported MSDs in college students and reported upper back (22%), shoulder (27.20%), neck (36.4%), and lower back (38%), which showed lower back a highly prevalent site and also supporting results of the present study [

28]. Conversely, in smartphone users, upper limb MSDs were observed at 20.13%, 5.11%, and 13.42%, in shoulder, elbow, and wrist/hand regions respectively during the pandemic of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia [

29]. An-Najah University in Palestine also showed a high occurrence of MSDs in e-device users for e-learning. They were having pain associated with difficulty in several daily activities and body aches [

4].

Results of the present study showed that disability was associated significantly with physical activity rather than pain intensity (p < 0.001) and 67% of participants including teachers and students were not doing any exercise at all in the present study. Ghanbari et al. and Deniz et al. studies showed that the pandemic of COVID-19 resulted in an interruption in education systems affecting more than 200 million students worldwide with fewer hours spent on physical activity, increased hours of using e-learning aids leading to increased musculoskeletal pain [

30,

31]. In the current study, pain in the shoulder and upper back has a significant tendency to increase due to bad posture. Inappropriate work posture plays a major role in the development of work-related MSDs. Spanish university students reported MSDs and pain in the spine and upper limb due to inappropriate posture but those who were doing moderate-intensity exercise had fewer symptoms during the lockdown period [

28]. There is changed muscular effort and tension on ligaments due to bad posture, which leads to MSDs. While sitting, back muscles are the least active, and load is conducted through passive structures causing viscoelasticity that results in pain [

32]. To concentrate on the monitor, forward head posture is adapted if the sitting position is not adjusted, which causes tension in the cervical, and lumber muscles and pressure on the intervertebral disc resulting in pain due to nerve irritations. Results of a systematic review conducted by Lis et al. (2007) reported that extended hours of static improper posture and more twists result in increased low back pain. [

33]. Repetitive touch to the screen or typing or clicking can result in microtrauma resulting in wrist and hand pain [

34,

35]. Sitting in front of the screen for a prolonged period leads to increased tone in the upper trapezius which further enhances neck and shoulder pain [

36]. A systematic review showed increased activity of upper limb muscles which can contribute to muscle fatigue and a decrease in pain threshold while using smartphones [

37]. Static posture during work with elevated arms and kyphotic posture leads to impaired circulation as the coracoacromial arch is compromised by the head of the humerus, lead to shoulder MSDs. While using screen there is need of repetitive movement of arms as well, this can lead to overuse injuries [

8,

38].

Similarly, the length of duration of e-device use was associated with MSD and females were more prone. Likewise, Al-Quds University students reported increased severity of MSDs like headaches, neck and back pain due to increased hours spent on e-devices with no difference in exercise time before or after lockdown [

23]. During the recent pandemic of COVID-19, academicians from Turkey who provided distance education reported discomfort in eyes, necks, and waists and increased MSDs associated with no regular exercise, more workload, and increased duration of mobile phone use [

31].

Strengths and Limitations

The findings provide insights into the prevalence, distribution, and associations of MSDs within the specific population of university students and faculty members involved in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. By focusing on individuals involved in online education, the study captures a unique and timely aspect of education. It provides valuable information about the musculoskeletal issues experienced by this specific population during a period of significant educational transformation. This firsthand perspective from the individuals suffering from MSDs can offer valuable insights into their subjective experiences, which may not be captured as effectively through objective measures alone. Moreover, by using a validated questionnaire, the study increases the likelihood of obtaining reliable and accurate data.

However, it’s important to consider the limitations of the study. A cross-sectional survey was conducted as it is quick, easy, and inexpensive with seldom ethical issues. On the other hand, it is difficult to make a causal inference, and the interpretation of associations is difficult. The self-reported questionnaire can lead to recall bias or misinterpretation of questions and may also overstate or understate their symptoms or experiences. The study focused on a specific population of university students and faculty members involved in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the results may not apply to other populations or contexts, such as individuals from different educational institutions or non-academic settings.

Conclusions:

A significant proportion of participants reported experiencing musculoskeletal symptoms or discomfort. Lower back, neck, and shoulders were identified as the primary sources of pain or discomfort among the participants. Students experienced musculoskeletal symptoms at a slightly higher rate than faculty members involved in online education. The leading reasons for higher MSDs were bad posture, long duration, and lack of physical activity with MSDs occurrence. A high occurrence of MSDs can be due to a lack of awareness about the proper posture among participants, which should be addressed at the institutional level. The factors explored in our study associated with MSDs should be considered for effective intervention to reduce the burden of the problem. Future studies focusing on exploring effective interventions and prevention strategies can be a good contribution to the body of literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Omar Althomali; Data curation, Junaid Amin, Tolgahan Acar and Salman Amin; Formal analysis, Junaid Amin and Raheela Kanwal; Funding acquisition, Bodor Bin Sheeha; Investigation, Raheela Kanwal, Omar Althomali, Salman Amin and Bodor Bin Sheeha; Methodology, Junaid Amin, Raheela Kanwal, Omar Althomali, Tolgahan Acar, Salman Amin and Bodor Bin Sheeha; Project administration, Bodor Bin Sheeha; Resources, Raheela Kanwal, Omar Althomali, Tolgahan Acar and Bodor Bin Sheeha; Validation, Tolgahan Acar; Visualization, Raheela Kanwal; Writing – original draft, Junaid Amin, Omar Althomali, Tolgahan Acar and Salman Amin; Writing – review & editing, Junaid Amin and Salman Amin.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R422), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó.; Pinto-Carral, A.; Álvarez-Álvarez, M.J.; Galán-Martín, M..; Montero-Cuadrado, F.; Benítez-Andrades, J.A. Musculoskeletal Pain and Non-Classroom Teaching in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of the Impact on Students from Two Spanish Universities. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Alshammary, F.; Amin, J.; Rathore, H.A.; Hassan, I.; Ilyas, M.; Alam, M.K. Knowledge and practice regarding prevention of COVID-19 among the Saudi Arabian population. Work 2020, 66, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawalia, A.; Joshi, S. Preeti. Yadav vs. prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and discomfort due to online teaching and learning methods during lockdown in students and teachers: outcomes of the new normal. J. Musculoskelet. Res. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Q.B.; Salah, H. The impact of e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic on students’ body aches in Palestine. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, I.; De Martelaer, K.; Deforche, B.; Clarys, P.; Zinzen, E. Associations between different types of physical activity and teachers’ perceived mental, physical, and work-related health. BMC public health 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althomali, O.W.; Amin, J.; Alghamdi, W.; Shaik, D.H. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Musculoskeletal Disorders among Secondary Schoolteachers in Hail, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putsa, B.; Jalayondeja, W.; Mekhora, K.; Bhuanantanondh, P.; Jalayondeja, C. Factors associated with reduced risk of musculoskeletal disorders among office workers: a cross-sectional study 2017 to 2020. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh S, Siddiqui AA, Alshammary F, Amin J, Agwan MAS. Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Healthcare Workers: Prevalence and Risk Factors in the Arab World. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. 2021:1-39.

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Maldonado-Macías, A.A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Baez-Lopez, Y.; Carrillo-Gutiérrez, T.; Hernández-Escobedo, G. The Impact of Environmental Factors on Academic Performance of University Students Taking Online Classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsh, B.-T. Theories of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: Implications for ergonomic interventions. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2006, 7, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Theories of musculoskeletal injury causation. Ergonomics 2001, 44, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.O. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire. Occup. Med. 2007, 57, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erick, P.N.; Smith, D.R. A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among school teachers. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Salam, D.M.; Almuhaisen, A.S.; Alsubiti, R.A.; Aldhuwayhi, N.F.; Almotairi, F.S.; Alzayed, S.M.; et al. Musculoskeletal pain and its correlates among secondary school female teachers in Aljouf region, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Public Health. 2021, 29, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabara, M. The association between physical activity and musculoskeletal disorders—a cross-sectional study of teachers. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-Y.K.; Wong, M.-T.; Yu, Y.-C.; Ju, Y.-Y. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomic risk factors in special education teachers and teacher’s aides. BMC Public Heal. 2016, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, D.; Ilhanli, I. Are there work-related musculoskeletal problems among teachers in Samsun, Turkey? J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabilitation 2012, 25, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Sorock, G.S.; Courtney, T.K. Prevalence of low back pain in three occupational groups in Shanghai, People's Republic of China. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, H.; Bulut, A.; Adalan, M.A. Investigation of the change of lockdowns applied due to COVID-19 pandemic on musculoskeletal discomfort. J. Hum. Sci. 2020, 17, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queme, L.F.; Jankowski, M.P. Sex differences and mechanisms of muscle pain. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2019, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, D.; Krebs, E.; Bair, M.; Damush, T.; Wu, J.; Sutherland, J.; Kroenke, K. Sex Differences in Pain and Pain-Related Disability among Primary Care Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AKINCI B, Zenginler Y, Begüm K, Aslıhan K, Yeldan İ. Beyaz Yakalı Çalışanlarda İşe Bağlı Boyun, Sırt ve Omuz Bölgelerine Ait Kas İskelet Sistemi Rahatsızlıklarının ve İşe Devamsızlığza Etki Eden Faktörlerin İncelenmesi. Sakarya Tıp Dergisi.8(4):712-9.

- Ay, M.K.; Karakuş, B.; Hıdıroğlu, S.; Karavuş, M.; Tola, A.A.; Keskin, N.; et al. Bir büronun beyaz yakalı çalışanlarında kas-iskelet sistemi yakınmaları ve ilişkili faktörler. Kocaeli Medical Journal. 2020, 9, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Y.M.; Voo, P.; Maakip, I. Psychosocial factors, depression, and musculoskeletal disorders among teachers. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayabınar, E.; Kayabınar, B.; Önal, B.; Zengin, H.Y.; Köse, N. The musculoskeletal problems and psychosocial status of teachers giving online education during the COVID-19 pandemic and preventive telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal problems. Work 2021, 68, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-González, P.; Šutvajová, M.; Lesňáková, A.; Bartík, P.; Buľáková, K.; Friediger, T. Back Pain Prevalence, Intensity, and Associated Risk Factors among Female Teachers in Slovakia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, D.M.; Almuhaisen, A.S.; Alsubiti, R.A.; Aldhuwayhi, N.F.; Almotairi, F.S.; Alzayed, S.M.; et al. Musculoskeletal pain and its correlates among secondary school female teachers in Aljouf region, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Public Health. 2021, 29, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.P.; Purohit, A. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorder among College Students in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic - An Observational Study. Int. J. Heal. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajudeen, M.S.; Alzhrani, M.; Alanazi, A.; Alqahtani, M.; Waly, M.; Manzar, D.; Hegazy, F.A.; Jamali, M.N.Z.M.; Reddy, R.S.; Kakaraparthi, V.N.; et al. Prevalence of Upper Limb Musculoskeletal Disorders and Their Association with Smartphone Addiction and Smartphone Usage among University Students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, L.; Khazaei, S.; Mortazavi, S.S.; Saremi, H.; Naderifar, H. The Effect of Online Teaching on the Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain in Female Students during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences & Research. 2022, 9, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yorulmaz, D.S.; Karadeniz, H.; Duran, S.; Çelik, I. Determining the musculoskeletal problems of academicians who transitioned to distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2022, 71, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörl, F.; Bradl, I. Lumbar posture and muscular activity while sitting during office work. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubert, L.; Crombez, G.; Bourdeaudhuij, I. Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: prevalence and interrelationships. Eur. J. Pain 2004, 8, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, M.S.B.; Choudary, A.B.; Jamal, S.; Kumar, R.; Jamal, S. The Impact of Ergonomics on Children Studying Online During COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Adv. Sports Phys. Educ. 2020, 3, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, E.; Johnson, P.W.; Hagberg, M. Thumb postures and physical loads during mobile phone use – A comparison of young adults with and without musculoskeletal symptoms. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachtiar F, Maharani FT, Utari D, editors. Musculoskeletal disorder of workers during work from home on covid-19 pandemic: a descriptive study. International conference of health development Covid-19 and the role of healthcare workers in the industrial era (ICHD 2020); 2020: Atlantis Press.

- Eitivipart, A.C.; Viriyarojanakul, S.; Redhead, L. Musculoskeletal disorder and pain associated with smartphone use: A systematic review of biomechanical evidence. Hong Kong Physiother. J. 2018, 38, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaker, C.H.; Walker-Bone, K. Shoulder disorders and occupation. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology. 2015, 29, 405–423. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).