Submitted:

03 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introducción

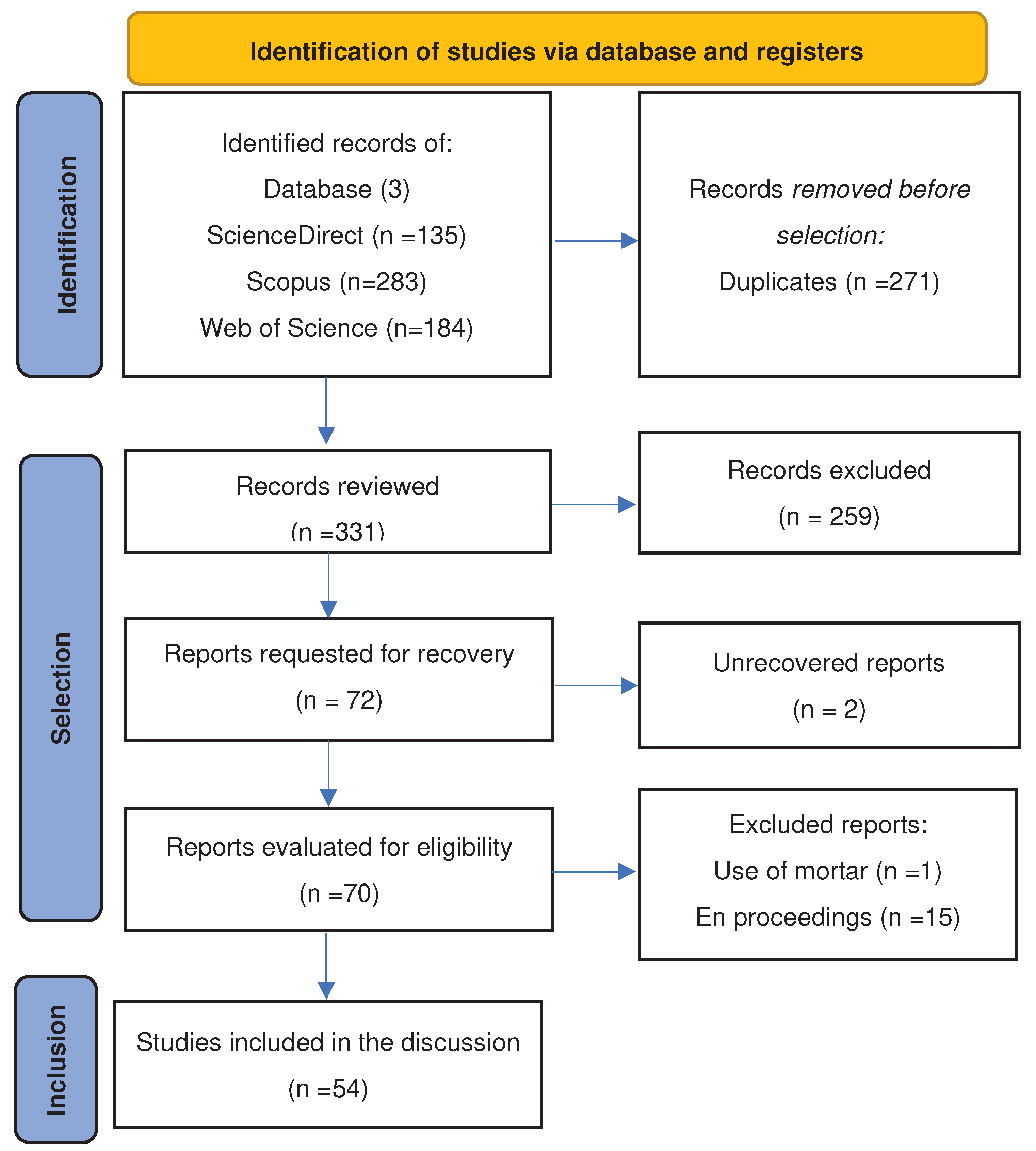

2. Methodology

2.1. Databases and search strategy

| Database | Search |

|---|---|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "self-healing") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Bacteria" OR "Bacillus" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "concrete" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE , "final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2022 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2021 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2020 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2019 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2018 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2017 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2016 ) OR LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR , 2015 ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar") ) |

| ScieceDirect | "self-healing" AND (Bacteria OR Bacillus) AND concrete NOT review |

| Web of Science | concrete + (Bacteria OR Bacillus OR microorganisms) +"self-healing" -review |

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.3. Data extraction and eligibility of items

2.4. Summary of included studies

3. Results

3.1. Compressive strength

3.2. Flexural strength

3.3. Tensile strength

3.4. Concrete self-healing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajczakowska, M. Self-Healing Concrete. Licentiate thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alhalabi, Z.S.; Dopudja, D. Self-healing concrete: definition, mechanism and application in different types of structures. 2017, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalla, M. Bacteria Based Self-Healing Concrete. A Master Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft-The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, K.; Sharma, T.; Alazhari, M.; Heath, A.; Cooper, R. Application and Performance of Bacteria-Based Self-Healing Concrete. In Proceedings of the Final Conference of RILEM TC 253-MCI: Microorganisms-Cementitious Materials Interactions, Toulouse-France, 2018; Vol. 2, pp. 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Souid, A.; Esaker, M.; Elliott, D.; Hamza, O. Experimental Data of Bio Self-Healing Concrete Incubated in Saturated Natural Soil. Data in brief 2019, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prošek, Z.; Ryparová, P.; Tesárek, P. Application of Bacteria as Self-Healing Agent for the Concrete and Microscopic Analysis of the Microbial Calcium Precipitation Process. In Proceedings of the Key Engineering Materials; Trans Tech Publ, 2020; Vol. 846; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Žáková, H.; Pazderka, J.; Rácová, Z.; Ryparová, P. Effect of Bacteria Bacillus Pseudofirmus and Fungus Trichoderma Reesei on Self-Healing Ability of Concrete. Acta Polytechnica CTU Proceedings 2019, 21, 45–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Feng, J.; Jin, P.; Qian, C. Influence of Bacterial Self-Healing Agent on Early Age Performance of Cement-Based Materials. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 218, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kua, H.W.; Gupta, S.; Aday, A.N.; Srubar, I., W. V. Biochar-Immobilized Bacteria and Superabsorbent Polymers Enable Self-Healing of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete after Multiple Damage Cycles. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 100, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmasi, F.; Mostofinejad, D. Investigating the Effects of Bacterial Activity on Compressive Strength and Durability of Natural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete Reinforced with Steel Fibers. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 251, 119032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifathima, S.; Lakshmi, T.; Matcha, B. Self-Healing Concrete by Adding Bacillus Megaterium MTCC with Glass & Steel Fibers. Civil and Environmental Engineering 2020, 16, 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Algaifi, H.A.; Bakar, S.A.; Alyousef, R.; Mohd Sam, A.R.; Ibrahim, M.H.W.; Shahidan, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Salami, B.A. Bio-Inspired Self-Healing of Concrete Cracks Using New B. Pseudomycoides Species. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 12, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.; Khushnood, R.A.; Khaliq, W.; Murtaza, H.; Iqbal, R.; Khan, M.H. Synthesis and Characterization of Bio-Immobilized Nano/Micro Inert and Reactive Additives for Feasibility Investigation in Self-Healing Concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 226, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannem, R.; Chintalapudi, K. Evaluation of Strength Properties and Crack Mitigation of Self-Healing Concrete. Jordan Journal of Civil Engineering 2019, 13, 386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, V.; Philip, N.; Baven, N. The Self-Healing Effect on Bacteria-Enriched Steel Fiber-Reinforced SCC. Ingenieria e Investigacion 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rais, M.S.; Khan, R.A. Experimental Investigation on the Strength and Durability Properties of Bacterial Self-Healing Recycled Aggregate Concrete with Mineral Admixtures. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.M.; Taher, F.M.; Abd EL-Tawab, A.; Faried, A.S. Role of Different Microorganisms on the Mechanical Characteristics, Self-Healing Efficiency, and Corrosion Protection of Concrete under Different Curing Conditions. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Ortoneda-Pedrola, M.; Nakouti, I.; Bras, A. Experimental Characterisation of Non-Encapsulated Bio-Based Concrete with Self-Healing Capacity. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 256, 119411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, G.; Ahmed, A.A.-E.-A.; Reyad, A.M. The Effect of Isolated Bacillus Ureolytic Bacteria in Improving the Bio-Healing of Concrete Cracks. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullem, T.; Gruyaert, E.; Caspeele, R.; Belie, N. First Large Scale Application with Self-Healing Concrete in Belgium: Analysis of the Laboratory Control Tests. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, K.; Murmu, M. Self-Repairing of Concrete Cracks by Using Bacteria and Basalt Fiber. SN Applied Sciences 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, I.M.; Elshami, A.A.; Elshikh, M.M.Y. Influence of Concentration and Proportion Prepared Bacteria on Properties of Self-Healing Concrete in Sulfate Environment. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.V.; Nehdi, M.L.; Suleiman, A.R.; Allaf, M.M.; Gan, M.; Marani, A.; Tuyan, M. Crack Self-Healing in Bio-Green Concrete. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, B.; Hussain, A.; Khattak, A.; Khan, A. Performance Evaluation of Bacterial Self-Healing Rigid Pavement by Incorporating Recycled Brick Aggregate. Cement and Concrete Composites 2021, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Pang, B. Effect of Fly Ash with Different Particle Size Distributions on the Properties and Microstructure of Concrete. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 2020, 29, 6631–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yao, W. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregates as Carriers for Self-Healing of Concrete Cracks by Bacteria with High Urease Activity. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Ali, A.M.; Faraz Bhatti, M.; Ahmed Khan, H. Self-Healing Fungi Concrete Using Potential Strains Rhizopus Oryzae and Trichoderma Longibrachiatum. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, I.; Padmapriya, R. Effect of Bateria Subtilis on Conrete Substituted Fully and Partially with Demolition Wastes. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 2018, 9, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, G.M.; Santhi, A.S.; Kalaichelvan, G. Self-Healing Bacterial Concrete by Replacing Fine Aggregate with Rice Husk. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 2017, 8, 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, M.; Adak, D.; Tamang, A.; Chattopadhyay, B.; Mandal, S. Genetically-Enriched Microbe-Facilitated Self-Healing Concrete–a Sustainable Material for a New Generation of Construction Technology. RSC advances 2015, 5, 105363–105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, M.; Khushnood, R.A.; Khaliq, W.; Wattoo, A.G.; Shahid, T. Synthesis of Pyrolytic Carbonized Bagasse to Immobilize Bacillus Subtilis; Application in Healing Micro-Cracks and Fracture Properties of Concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites 2022, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, C.; Muthukannan, M.; Kumar, A.S.; Arunkumar, K. Influence of Bacterial Strain Combination in Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete Subjected to Heavy and Very Heavy Traffic Condition. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2021, 19, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Qureshi, Z.A.; Shaheen, N.; Ali, S. Bio-Mineralized Self-Healing Recycled Aggregate Concrete for Sustainable Infrastructure. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayuda, H.; Soebandono, B.; Cahyati, M.D.; Monika, F. Repairing of Flexural Cracks on Reinforced Self-Healing Concrete Beam Using Bacillus Subtillis Bacteria. International Journal of Integrated Engineering 2020, 12, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, N.N.T.; Imamoto, K.-I.; Kiyohara, C. A Study on Biomineralization Using Bacillus Subtilis Natto for Repeatability of Self-Healing Concrete and Strength Improvement. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2019, 17, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.N.; Kavyateja, B.V. Experimental Study on Strength Parameters of Self Repairing Concrete. Annales de Chimie: Science des Materiaux 2019, 43, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, W.; Ehsan, M.B. Crack Healing in Concrete Using Various Bio Influenced Self-Healing Techniques. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 102, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshahmohammad, M.; Rahmani, H.; Maleki-Kakelar, M.; Bahari, A. Effect of Sustained Service Loads on the Self-Healing and Corrosion of Bacterial Concretes. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xing, L.; Liu, H.; Huang, W.; Nong, X.; Xu, X. Experimental on Repair Performance and Complete Stress-Strain Curve of Self-Healing Recycled Concrete under Uniaxial Loading. Constr Build Mater 2021, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yao, W. Application of Ureolysis-Based Microbial CaCO3 Precipitation in Self-Healing of Concrete and Inhibition of Reinforcement Corrosion. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, G.A.; Mahdy, M.; Abd El, A.E.-R.H. Performance of Bio Concrete by Using Bacillus Pasteurii Bacteria. Civil Engineering Journal 2020, 6, 1443–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chen, M.-C.; Tang, C.-W. Research on Improving Concrete Durability by Biomineralization Technology. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhi Kala, R.; Chandramouli, K.; Pannirselvam, N.; Varalakshmi, T.V.S.; Anitha, V. Strength Studies on Bio Cement Concrete. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 2019, 10, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kadapure, S.A.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Prakash, K.B. Biomineralization Technique in Self-Healing of Fly-Ash Concrete. International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development 2017, 8, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Irwan, J.M.; Anneza, L.H.; Othman, N. Effect of Enterococcus Faecalis Bacteria and Calcium Lactate on Concrete Properties and Self-Healing Capability. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology 2019, 10, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Goyal, S.; Sudhakara Reddy, M. Bio-Consolidation of Cracks with Fly Ash Amended Biogrouting in Concrete Structures. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Guo, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, H.; Xiong, X.; Krastev, R.; Nie, K.; Xu, H.; Liu, L. Immobilized Bacteria with PH-Response Hydrogel for Self-Healing of Concrete. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiberova, H.; Trtik, T.; Chylik, R.; Prosek, Z.; Seps, K.; Fladr, J.; Bily, P.; Kohoutkova, A. Self-Healing in Cementitious Composite Containing Bacteria and Protective Polymers at Various Temperatures. Magazine of Civil Engineering 2021, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, M.; Qian, C. Effects of Carrier on the Performance of Bacteria-Based Self-Healing Concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y. Application of Microbial Self-Healing Concrete: Case Study. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer Algaifi, H.; Abu Bakar, S.; Rahman Mohd. Sam, A.; Ismail, M.; Razin Zainal Abidin, A.; Shahir, S.; Ali Hamood Altowayti, W. Insight into the Role of Microbial Calcium Carbonate and the Factors Involved in Self-Healing Concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, N.; Surabhi, R.; Yathish, N.V.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Deepa, T.; Tharannum, S. Enhancement in Strength Parameters of Concrete by Application of Bacillus Bacteria. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 202, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durga, C.S.S.; Ruben, N.; Chand, M.S.R.; Venkatesh, C. Evaluation of Mechanical Parameters of Bacterial Concrete. Annales de Chimie: Science des Materiaux 2019, 43, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Pal, S.; Puria, R.; Nain, V.; Pathak, R.P. Microbial Crack Healing and Mechanical Strength of Light Weight Bacterial Concrete. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 2018, 9, 721–731. [Google Scholar]

- Vashisht, R.; Attri, S.; Sharma, D.; Shukla, A.; Goel, G. Monitoring Biocalcification Potential of Lysinibacillus Sp. Isolated from Alluvial Soils for Improved Compressive Strength of Concrete. Microbiological Research 2018, 207, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnapriya, S.; Venkatesh Babu, D.L.; G., P.A. Isolation and Identification of Bacteria to Improve the Strength of Concrete. Microbiological Research 2015, 174, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, M.; Khaliq, W.; Khushnood, R.A.; Ahmed, I. Comparative Performance of Different Bacteria Immobilized in Natural Fibers for Self-Healing in Concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhath Ranjan Kumar, S.; Vighnesh, R.; Karthikeyan, G.; Maiyuri, S. Self-Healing of Microcracks in Linings of Irrigation Canal Using Coir Fibre Reinforced Bio-Concrete. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering 2019, 8, 3275–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lian, J.; Gao, M.; Fu, D.; Yan, Y. Self-Healing Concrete Using Rubber Particles to Immobilize Bacterial Spores. Mater. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chithambar Ganesh, A.; Muthukannan, M.; Malathy, R.; Ramesh Babu, C. An Experimental Study on Effects of Bacterial Strain Combination in Fibre Concrete and Self-Healing Efficiency. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2019, 23, 4368–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njau, M.W.; Mwero, J.; Abiero-Gariy, Z.; Matiru, V. Effect of Temperature on the Self-Healing Efficiency of Bacteria and on That of Fly Ash in Concrete. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology 2022, 70, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, X.; Alazhari, M.; Yang, B.; Zhang, G. Characterisation of Bacteria-Based Concrete Crack Rejuvenation by Externally Applied Repair. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology (New Series) 2020, 27, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.X.; Cheng, X.H. Role of Calcium Sources in the Strength and Microstructure of Microbial Mortar. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 77, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (year) | Country | Author (year) | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (2022) | China | Mullem et al. (2020) | Belgium | |

| Khushnood et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Chen et al. (2020) | Taiwan | |

| Njau et al. (2022) | Kenya | Prayuda et al. (2020) | Indonesia | |

| Mirshahmohammad et al. (2022) | Iran | Shaheen et al. (2019) | Italia | |

| Kanwal et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Vijay & Murmu (2019) | India | |

| Riad et al. (2022) | Egypt | Chithambar Ganesh et al. (2019) | India | |

| Raman et al. (2022) | India | Prabhath Ranjan Kumar et al. (2019) | India | |

| Zhang et al. (2021) | Canada | Xu et al. (2019) | China | |

| Mokhtar et al. (2021) | Egypt | Kua et al. (2019) | U.S.A. | |

| Rais & Khan (2021) | India | Santhi Kala et al. (2019) | India | |

| Zhang et al. (2021) | China | Nain et al. (2019) | India | |

| Joshi et al. (2021) | India | Huynh et al. (2019) | Japan | |

| Osman et al. (2021) | Egypt | Durga et al. (2019) | India | |

| Qian et al. (2021) | China | Reddy & Kavyateja (2019) | India | |

| Liu et al. (2021) | China | Irman et al. (2019) | Malaysia | |

| Ganesh et al. (2021) | India | Pannem & Chintalapudi (2019) | India | |

| Saleem et al. (2021) | Pakistan | Tiwari et al. (2018) | India | |

| Schreiberova et al. (2021) | Czech Republic | Rohini & Padmapriya (2018) | India | |

| Algaifi et al. (2021) | Malaysia | Vashisht et al. (2018) | India | |

| Xu et al. (2020) | China | Ganesh et al. (2017) | India | |

| Pourfallahi et al. (2020) | Iran | Kadapure et al. (2017) | India | |

| Rauf et al. (2020) | Pakistan | Khaliq & Ehsan (2016) | Pakistan | |

| Amer Algaifi et al. (2020) | Malasia | Krishnapriva et al. (2015) | India | |

| Yuan et al. (2020) | China | Sarkar et al. (2015) | India | |

| Metwally et al. (2020) | Egipt | Salmasi & Mostofinejad (2020) | Iran | |

| Gao et al. (2020) | China | Mohammed et al. (2020) | England | |

| Khushnood et al. (2020) | Italy | Bifathima et al. (2020) | India |

| Type of material and its references | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Industrial | Author | Natural |

| Fibers | |||

| 36, 52, 54 | Steel fiber | 16, 31 | Coconut fiber |

| 7, 36 | Polyvinyl alcohol fibers (PAF). | 19 | Jute fiber |

| 16, 54 | High modulus glass fibers | 19 | Flax fiber |

| 15 | Low modulus polypropylene fibers | 43 | Rice husk |

| 29 | Basalt fiber | --- | --- |

| 30 | Polypropylene fiber | --- | --- |

| 32 | Rubber fiber | --- | --- |

| Particles | |||

| 8, 10, 13, 53 | Granulated slag; granulated ground blast furnace slag (GGBFS) | 5 | Ground biochar |

| 9 | Silica fume (MS) | 17 | Crushed granite |

| 28 | Nano/microparticles: iron oxide | 6, 12 | Dolomite |

| 28 | Nano/microparticles: bentonite (clay) | 9 | Metakaolin (MK) |

| 18 | Ceramsite | --- | --- |

| 7 | Expanded glass (EG). | --- | --- |

| Ashes | |||

| 3, 10, 11, 13, 20, 24, 43, 48 | fly ash | --- | --- |

| Recycled construction waste material | |||

| 1, 9, 14, 27, 45 | Recycled concrete | --- | --- |

| Bacteria(s) | Experimental Designs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One group and one control | Two groups and a control | More than two groups and control | Factorials | Conditions involved | |

| Sporosarcinapasteurii | 1, 43 | 29 | 4, 8, 15, 20, 24, 37* | 25, 48* | Substrate type: Urea, Ca(NO3)2; NH4Cl, calcium lactate/calcium acetate/expanded glass/adsorption to recycled coarse aggregate/fly ash/relative humidity/water/cement ratio, compressive strength/light aggregate/cement concentration*/fly ash concentration*/crack depth. |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | — | 3 | — | — | Fly ash |

| Bacillus subtilis | 30, 39 | 51 | 5, 7, 16, 17, 27, 31, 52, 49 | 32, 41*, 45* | Presence of biocarbon/silica*/Fiber type (glass, hybrid)/Recycled brick*/Bacteria immobilization and/or suspension/Basalt fiber/Bacterial concentration and substrate concentration (Ca lactate)/ % recycled aggregates and bacterial concentration*/Genetically enhanced bacteria vs. unmodified bacteria/environment (water, urea-calcium lactate, culture broth, steel fiber). |

| Bacillus sphaericus | — | — | 36 | — | Superabsorbent polymers A and B, fiber, biocarbon immobilizer. |

| Bacillus megaterium | — | — | 10, 54* | 34 | Coarse aggregates NCA (granite), RCA (Concrete Probe), Metakaolin, Microsilica/Fiber, CaCl2 Cured/Fiberglass Fiber*, Steel Fiber*. |

| Bacillus sp. | — | — | 12* | — | Class F fly ash |

| Bacillus pseudofirmus | — | — | 26* | 18 | Polymer type: Superabsorbent polymer (SPA), Polyvinyl alcohol/ Encapsulation of bacteria at different concentrations of chitosan. |

| Bacillus cohnii | — | — | — | 47 | Replacement of fine sand with rice husks. |

| Bacillus pseudomycoides | 19 | — | — | — | — |

| Bacillus paralicheneniformis y Bacillus sp. | — | — | — | 21 | Cement type, anti-sulfate, slow sulfate infiltration |

| Enterococcus faecalis | — | — | 42* | — | Calcium lactate concentration* |

| Cepa tipo Shewanella | — | — | — | 53 | Ground granulated slag (GGBS) |

| Comparisons among bacteria | |||||

| Sporosarcina pasteurii vs Bacillus Sphaericus | — | — | — | 6*, 23* | Substrate: Calcium lactate/ Bacterial concentration. |

| Rhizopus oryzae vs Trichoderma longibrachiatum | — | — | — | 2 | Immobilizer (superplasticizer 1%). |

| B.subtilis vs B.cohnii vs B. sphaericus | — | — | — | 22 | Type of fiber (coconut, flax, jute) |

| B. subtilis vs B. megaterium vs consorcio | — | — | 38 | — | — |

| B.subtilis vs B.Halodurans | — | — | 40* | — | Bacterial concentration |

| Bacillus wiedmannii vs Bacillus paramycoides | — | 9 | — | — | — |

| B. megaterium MTCC1684 vs B. megaterium BSKNAU, B. flexus BSKNAU, B. licheniformis AS-4 | — | — | 50 | — | — |

| B. sphaericus vs B. Cohnii vs B. megaterium | — | — | 44 | — | — |

| B. sphaericus NCIM NO 2478 vs B. pasteruii NCIM NO 2477 | — | — | — | 48* | Fly ash concentration*, bacteria concentration. |

| B. megaterium vs Lysinibacillus sp. | — | 46 | — | — | — |

| B. sphaericus EMCC 1253 vs B. Pasteurii DSM33 vs Dunaliella salina | — | — | 13* | — | Bacterial concentration* |

| Combinations of microorganisms | |||||

| B. subtilis y B. sphaericus | — | — | — | 16 | Type of fiber (glass, hybrid glass + polypropylene). |

| B.subtilis y B.sphaericus | — | — | — | 33 | Propylene fiber |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).