1. Introduction

The rural revitalization strategy is a long-term national policy presented by the Communist Party of China. Because of China’s persistent urban-rural divide, which revolves around the “price scissors” method of operation [

1], rural areas in China are socially and economically less developed than their urban counterparts. As China’s reforms and opening began to ease restrictions on population mobility, higher-paying jobs and improved urban living standards attracted rural residents to cities [

2]. With the depopulation of rural areas in China, the issues of labor loss, arable land abandonment, and the increasing number of people left behind in the countryside have become increasingly severe, resulting in the problem of “hollowing out” of these areas. According to Guo, rural hollowing, which is described as “outward expansion with inside hollowing”, is a phenomenon that is harmful to sustainable rural development in the process of urbanization and industrialization [

3]. The hollowing out of China’s rural areas, while not a uniquely Chinese phenomenon [

4], is largely a historical product of state policy influences. Now, China’s “Rural Revitalization Strategy” indicates a move away from past policies, which favored urban development, to the rural biased policy, which gives priority to agricultural and rural development [

5]. Since policies no longer hinder rural development, the challenges faced by rural areas regarding economic development have become the center of scholarly discourse on rural decline. Incomes earned by farmers through traditional agriculture are considerably lower than those earned through non-agricultural work in urban areas. Some studies indicate that the larger the proportion of non-agricultural industries, the higher the corresponding degree of non-agriculturalization and urbanization of farmers, and the higher degree of rural hollowing [

6]. These findings suggest that traditional agriculture outputs can no longer satisfy the needs of the rural population to achieve their own development. Since rural areas primarily derive income from land, the issue of rural hollowing-out is essentially a problem of rural land use, which Ma refers to as “the long-term imbalance between the functional supply of rural land use and the functional demand for rural development [

7].” Consequently, to achieve rural revitalization through economic development, it is imperative to prioritize the rural land matter.

Due to the influence of China’s early land policies, “land fragmentation” is the prevalent form of land in rural areas. The random scattering of land in the countryside reduces the efficiency of land use and thus adversely affects the outcome of agricultural production [8-10].To address the issues caused by the land fragmentation, the concept of land consolidation was introduced and is still used today [

11].Land consolidation has the advantage of concentrating fragmented land by adjusting the ownership structure of the land [

12], and this concentration ultimately brings together dispersed factors such as labor and capital, leading to large-scale agricultural production [

13,

14]. Land consolidation in China has progressed rapidly in recent years, despite a late start. The shareholding cooperative system in Shenzhen and the “land bill system” in Chongqing indicate that land consolidation in China is being explored in various approaches [

15]. As a crucial part of China’s rural revitalization strategy, land consolidation is regarded as an essential approach to restructure rural agricultural resources [

16]. Emphasizing the “reorganization of rural resources,” land consolidation starts with land concentration and extends to every facet of rural economic development, living standards, and environmental well-being. As a result, China has a much larger land consolidation workload, the ultimate goal of which is the establishment of a sustainable rural spatial governance system [

17]. To accomplish this objective, Chinese scholars have summarized the correlation between land consolidation and rural revitalization in terms of the development elements of land consolidation, action programs, and regional characteristics [

18]. The existing research indicates that land consolidation in rural China can increase the area of arable land, expand the scale of agricultural production [

19], and enhance the quality of rural living conditions [

20]. This enables a more integrated and mutually beneficial cooperative development model between rural and urban areas and ultimately activates the endogenous driving forces of rural population, land, and industry [

21]. Existing research confirms that reforming the land system in rural China, with land consolidation as its core [

22], is a crucial prerequisite for the revitalization of rural areas. Scholars have categorized the fundamental types [

23], features [

24], and action logic of land consolidation [

25], which provides academic foundation for the further development of land consolidation in China. However, China’s rural revitalization strategy should encompass various domains including economics, politics, culture, and societal progress, while current discussions on land consolidation primarily prioritize economic development and environmental conservation [

26] [

20], often overlooking the significance of legal and political aspects pertaining to land consolidation. As Liu suggests, rural revitalization is not a simple economic issue; instead, it should go beyond the scope of industrial development and the economy and pay more heed to cultural trend dimensions [

27]. The absence of studies exploring the effects of land consolidation on rural democratization and the rule of law has resulted in a gap within current literature.

This paper analyzes the effects of land consolidation on Chinese rural society, revealing that it leads to the abandonment of traditional ways of thinking by rural residents and stimulates their demand for more democratic election and negotiation procedures. By examining typical cases in rural areas, this paper shows that when disputes arise between villagers and investors, traditional rural elites have lost the ability to resolve disputes, and villagers are taking the initiative to have disputes adjudicated according to the law. The paper discusses democratization and the rule of law in rural areas, exposing their ongoing modernization process, and filling the gap in the research on the impact of land consolidation on rural society development. The paper is organized as follows.

The first section is the introduction. First, with the theme of rural revitalization, it reviews the reason for the hollowing out of China’s countryside and emphasizes that China’s rural revitalization needs to start with the reform of the land system. Second, the relevance of rural revitalization and land consolidation is introduced. Finally, identify research gaps from existing literature and put forward research propositions. The second section is the analytical framework. The relationship between economic development and democratic politics and the rule of law is briefly described, and an analytical framework for land consolidation to promote the democratization of rural politics and the legal consciousness is constructed. The third section is the methodology. The study area, research methodology, specific implementation process, and data sources are presented in more detail, as well as the political and legal challenges that land consolidation brings to rural China. The discussion is presented in the fourth section. The fifth section is the final section, presenting conclusions, and several specific policy recommendations are made based on the finding.

2. Analytical Framework

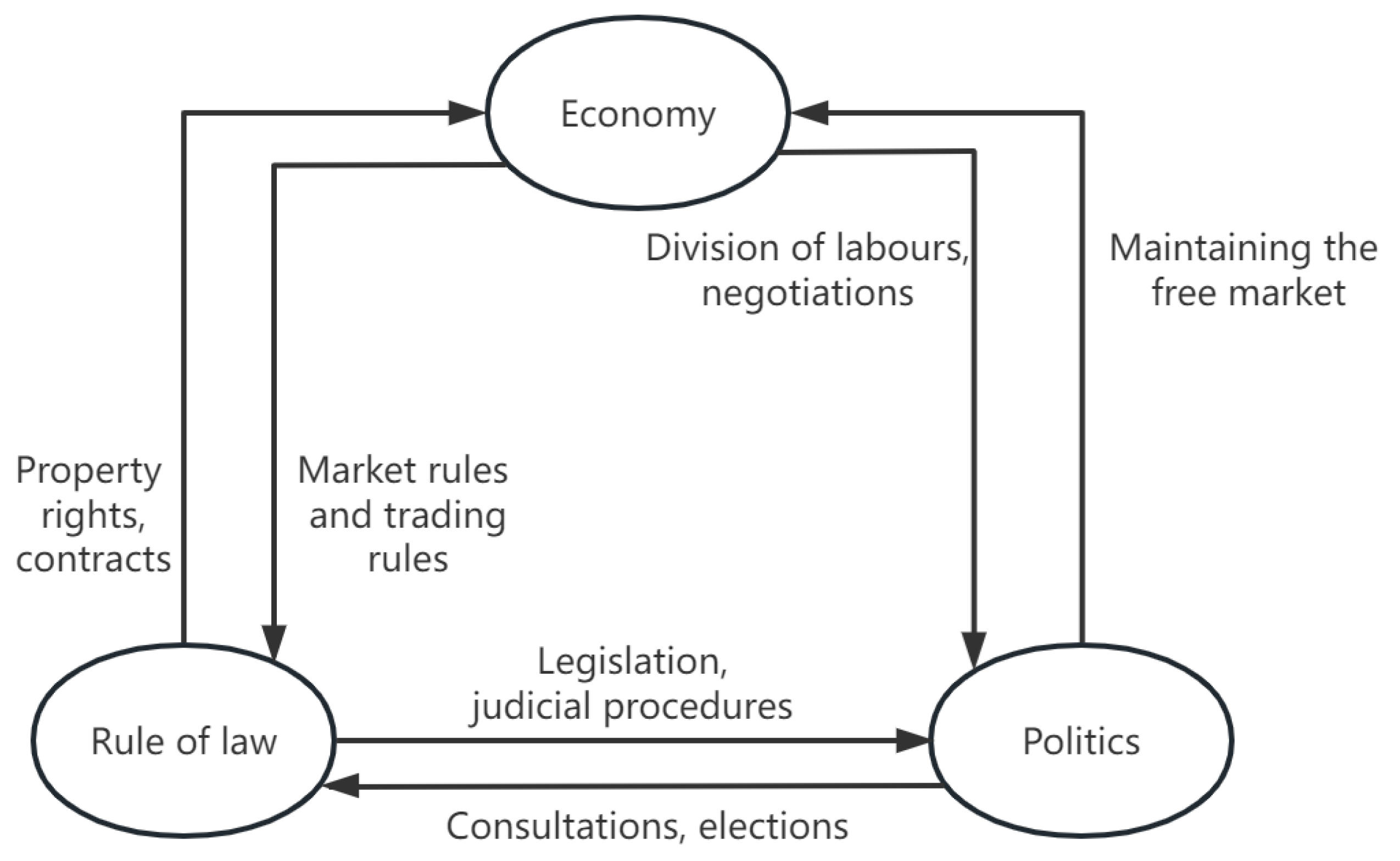

Since the 20th century, scholars of political economy have studied the correlation between economic development, democratic politics and the rule of law. Economic growth has the potential to significantly benefit the advancement of democratic politics. On one hand, economic development necessitates liberty in the allocation of economic resources, akin to the democratic political call for freedom of speech. On the other, economic development has led to a division of labor in society, making it more difficult to acquire knowledge across sector [

28]. As a result, individuals have to depend on the expertise of others to form judgements, creating an opportunity for consultation and negotiation, which strengthens political democratization. Some studies have shown that democratization promotes economic growth when the level of political freedom is low [

29]. This is because a democratic political environment ensures that the market environment is less subject to political bias, while democracies tend to favor less restrictive government regulatory policies. In terms of the relationship between the economy and the rule of law, the trade usages developed in the market via the use of commercial chambers and similar entities may enhance the legal consciousness of market participants [

30]. The rule of law supports investment and trade by ensuring the protection of property rights and contract reliability, thereby promoting economic growth and development [

31]. The interaction between the rule of law and democracy can be described through the following model: Firstly, democracies establish laws through representative democracy. Secondly, the rule of law assesses the outcomes of democratic politics and rectifies any violations through an efficient judicial system. In summary, economic development, democracy, and the rule of law mutually influence each other, and the relationship between them is depicted in

Figure 1.

When we focus on China’s land consolidation project, we are interested in how it promotes the level of democratization and the rule of law.

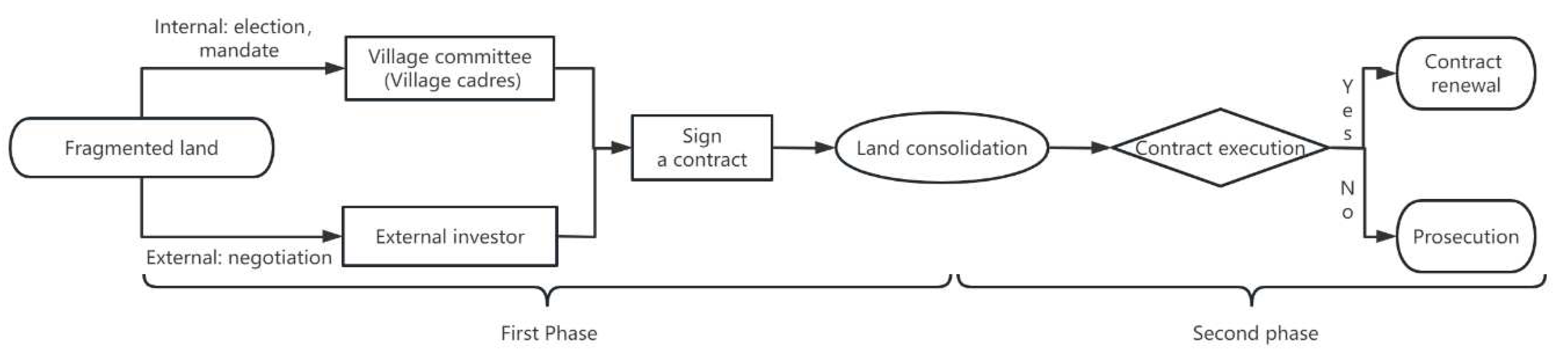

Figure 2 displays the process of land consolidation, which focuses on centralizing fragmented land into a single block of land. Categorized based on the relationship between participants, the main elements of the first phase can be roughly divided into two parts. In internal relations, the participants are the villagers who own the land. They engage in negotiations to reach a consensus on an external course of action through voting. In addition, the villagers usually designate village representatives, who are typically village cadres, to act as agents of their collective will and represent them in external affairs. In the external relationship, the participants are mainly the investor and the villagers. The investor engages in negotiations with the villagers in order to centralize land. Negotiations cover the fundamental aspects of the land, the methodology employed by the investor in centralizing the land, the approach and quantity of the villagers’ income, and the final outcome of the negotiations is rendered in a contract signed by both the investor and the villagers.

After centralizing fragmented land, the second phase of land consolidation is initiated, which involves the production of land and the distribution of its benefits. Investors production activities on the centralized land usually change the land's original crops and boundaries, and sometimes even the land’s use. For the villagers, the primary concern is if they will receive the contractual benefits from consolidating the land. If the investor fulfills the contract as promised, there are no issues. However, if the investor defaults, the villagers must decide whether to let the investor find someone else to continue the contract, or to cancel the contract and to pursue legal action against the defaulting investor.

Consistent with the progress of land consolidation, the analysis logic of this paper is also divided into two parts. In the first phase of the transformation from “fragmented land” to “concentrated land”, villagers discussed the transfer of land use rights in the form of villager conference, reflecting the element of equality in democratic politics. Furthermore, the villagers participate in selecting their representatives by voting, further enhancing the impression of political democratization. When negotiating with external investors, the villagers requested that the negotiation outcomes be established by a contract, demonstrating their confidence in the property rights protection system under the legal framework and showcasing the awakening of Jin’an villagers’ legal consciousness. In the second phase, it focuses on the fact that after the investor was unable to fulfill the contract, the villagers chose to go to court as the ultimate means of resolving the dispute. This implies that as long as villagers are involved in the land consolidation process, they are able to increase their legal consciousness, irrespective of the success of the land consolidation outcomes. In addition, the critique from villagers toward village cadres indicates that traditional authority, represented by the “rural elite,” has been degraded to an ordinary member of the rural community because of their inability to solve the problems arising from the land consolidation process. This situation has also contributed to the democratization of rural politics in China.

3. Empirical Case Analysis

3.1. Case Study Area Overview

In 2014, the General Office of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the State Council issued the Opinions on Guiding the Orderly Transfer of Rural Land Management Rights and Developing Adequate Scale Operations in Agriculture. The reform of the transfer of rural land management rights emphasized three key elements: (1) The ownership rights, the contracted management rights and the management rights of rural land are three distinct types of rights, and an investor can only obtain the management rights of the land. (2) Encourage local communities to develop innovative methods for transferring land management rights, in order to consolidate fragmented land into contiguous parcels. (3) Supporting and guiding farmers to transfer their land management rights on a long-term basis, and facilitating the transfer of farmers’ labor from agriculture to other industries. It can be seen that allowing farmers to transfer their land management rights is the predominant method of implementing large-scale land consolidation in China.

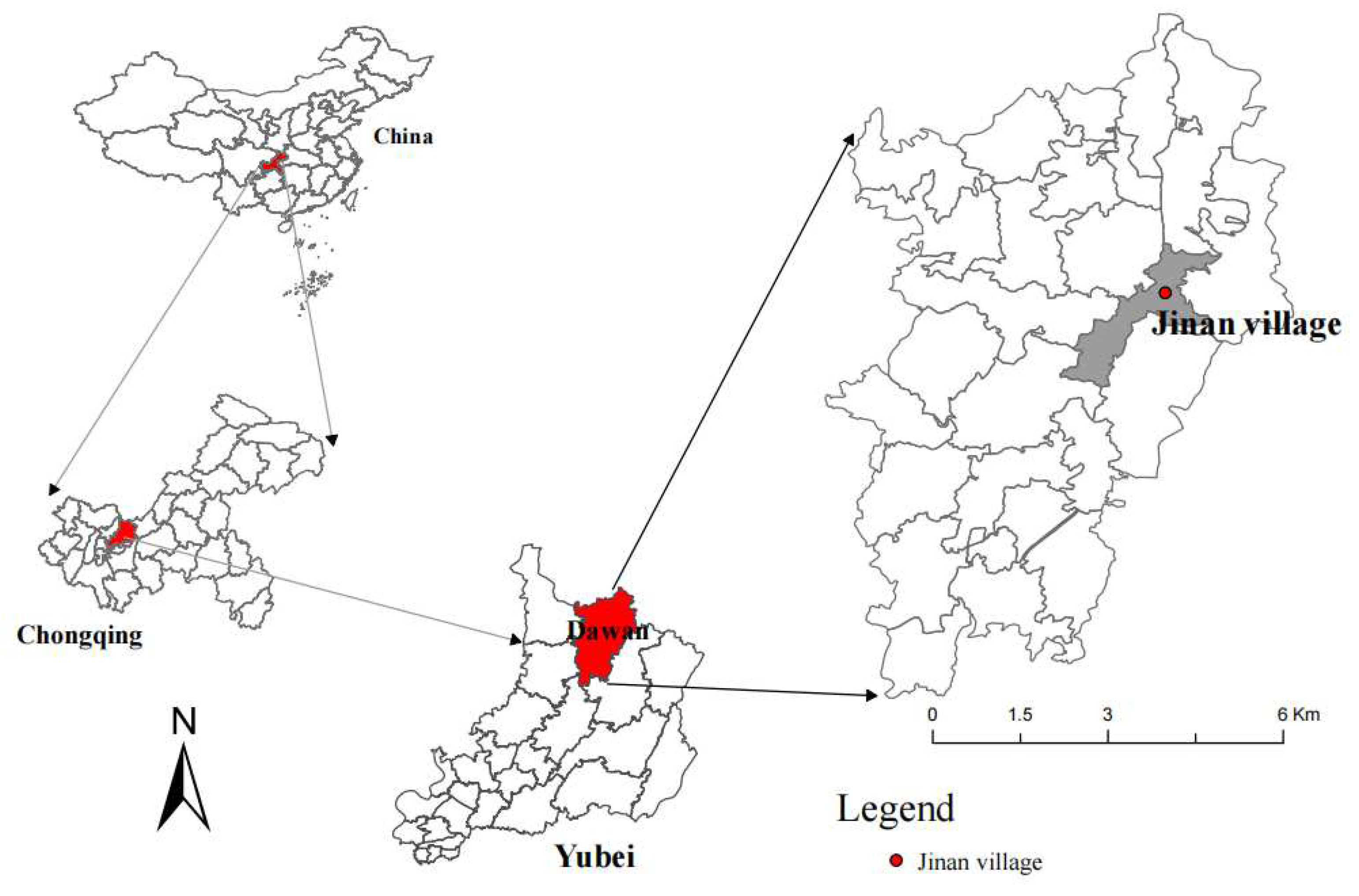

Chongqing is the direct-administered municipality with the largest area of rural land in China. As one of the initial pilot areas for land consolidation, Chongqing has made numerous attempts at consolidating land, including cooperative management, sharing of management rights, and leasing of management rights. In 2017, the Yubei government of Chongqing issued a Circular on Further Regulating the Transfer of Rural Land Contracted Management Rights to reinforce its support for land consolidation projects in Chongqing. In China, public administration take place at six levels: nation, province, city, county, town, and village [

32]. Dawan Town, located in Yubei District, Chongqing, serves as a pilot area for land consolidation in China.

Following the preceding discussion, we have selected the land consolidation case in Jin’an Village of Dawan Town for our study due to its unique characteristics that attracted our attention. Firstly, the village is not a typical remote rural area as it is located only 40 kilometers away from the city. The easy and efficient transportation link between the village and the city helps in minimizing storage and transportation expenses, which entices external investors to establish businesses in the village. Secondly, since the Chongqing government does not allow non-agricultural construction on agricultural land, the land consolidation in the Jin’an village has been carried out with the aim of expanding the scale of agricultural production. When discussing land consolidation in Jin’an Village, it is feasible to avoid confusion with land consolidation aimed at developing the tourism and real estate industries. Thirdly, during the implementation of land consolidation in this village, the investor removed the original land boundaries, resulting the fragmented land was not only legally but also physically connected. Consequently, the difficulty of determining the exact location of land rights makes it challenging for farmers to recover their land boundaries. This situation has rarely been mentioned in previous literature.

Dawan Town is situated in the northern part of Yubei District, Chongqing. The land usage consists of fifty percent mountainous terrains, forty percent arable lands, three percent water bodies, and seven percent transportation and residential lands. Jin’an Village is situated in a mountainous area, which forms part of Dawan Township, in the northeastern area of Yubei District and is located approximately 50 kilometers away from the center of Yubei District (as present in

Figure 3). The arable land area of Dawan Township is among the highest in Yubei District, and it is the main agricultural production site in Yubei district. Jin’an Village, like other villages in Dawan Township, specializes in traditional grain cultivation, with oilseed rape as the main cash crop. The objective of Dawan Township's development strategy is to draw in external investors and boost tourism by focusing on the advancement of local specialty agriculture. Jin’an Village is located next to a highway leading to the central city, and based on these advantaged endowments of resources, it became one of the first villages in Chongqing to undergo large-scale land consolidation.

3.2. Research Methods and Material Collection

This paper is a qualitative study, aiming to investigate the correlation between rural land consolidation, rural democratization, and the rule of law. It also evaluates the impact of land consolidation on rural political democratization and legal consciousness. We visited the village twice, in September 2019 and April 2023. The purpose of the 2019 study was to investigate the implementation of land consolidation both within and outside of the village during the first phase period. Our 2023 study aimed to explore the attitudes of villagers in viewing land transfer and their responses during the second phase of land consolidation, especially in the situation of the investor’s inability to fulfill a contract.

In regard to material collection, in addition to population and land data obtained from official sources, this study utilized semi-structured interviews and semi-participatory observation methods during fieldwork. We chose several types of actors to interview in Jin’an Village, including individuals from different groups such as villagers, village cadres, and investors. The outline of the interviews was set based on the objectives of the study, research experience and relevant literature (

Table 1). The semi-structured interviews method has the advantage of flexibility, being able to stimulate the initiative of both sides of the conversation and create a sense of trust in the course of the conversation. Although the method of semi-participatory observation creates a distance between ourselves and the villagers, provides a shallow understanding of the problem and observed information is more scattered, this information still able to validate the authenticity of the content of the interviews and to add some details that were not mentioned during the interviews.

3.3. A case of Land Consolidation in Jin’an Village

Since 2014, Dawan Town has undertaken large-scale land consolidation using the transfer of land management rights as the primary approach (this is called “land transfer”), and Jin’an Village is among them. Jin’an Village practices traditional agriculture, and most of the land in the village is arable land. As a result, the entities undertaking land consolidation within the village are primarily agro-forestry enterprises, aiming to enable large-scale cultivation. In 2019, upon arriving in Jin’an Village for our research, we discovered that the village had basically completed its land consolidation work, with the exception of some villagers who refused to lease their land. In 2023, we revisited Jin’an Village due to payment issues regarding the land consolidation project. Following the completion of the first phase of land consolidation work, the investor failed to fulfill their contractual rent obligations to the villagers. In other words, Jin’an Village encountered difficulties with revenue distribution during the second phase of the project. The purpose of our research at this point was to elucidate the perceptions of the villagers concerning land consolidation and their subsequent reactions when they did not receive land rents.

3.3.1. First Phase: Concentration of Fragmented Land

The status of land in Jin’an Village has captured the interest of many external investors. Since 2011, investors have been coming to Jin’an Village to investigate the local agricultural environment. In 2013, investors resolved to undertake land consolidation, aiming to gather land under the control of villagers to form a contiguous farmland in Jin’an Village. Because the majority of Jin’an Village residents are elderly, they lack knowledge of external investors, as well as an understanding of land consolidation and related policies. Consequently, when investors approached them, the villagers were wary and believed that the investors were trying to cheat them out of their land. In the end, the investors abandoned one-on-one negotiations with the villagers and opted to communicate with the Jin’an Village Committee members instead, intending to persuade the villagers to rent out their land use rights through the influence of the village cadres.

When Jin’an Village Committee agreed to cooperate with investors on land consolidation, the village cadres became the main executors of the land transfer work. Village cadres went door-to-door throughout the village to persuade villagers to lease their land use rights. One villager told us, “Village cadres came to my house every week to publicize the land transfer work in the village, even several times a day. Sometimes they came alone, sometimes in groups of three or five. The village cadres told us that those investors had come to build the village, to help it develop and to lead us to prosperity. The investors want to concentrate the land for large-scale agricultural development, so that we can receive higher and higher rents in the future. Because the village cadres and we are all neighbors in the same village and they are more educated, I trust what they say.” (Interview with villager, 20190826) Under the persuasion of village cadres, Jin’an villagers have been enticed by the land rental rates, which exceed the profits from their own agricultural activities. This has addressed their apprehensions towards external investors. Nonetheless, Jin’an villagers still reluctant to sign a land-use rights transfer contract with an investor because they felt that “there is no guarantee of doing business with the outsiders.”

Eventually, the procedure of the land transfer contract was concluded after a tripartite negotiation between the investor, the Village Committee and the villagers: first, village cadres visit each villager’s home to inform them that the Village Committee would negotiate with the investor and receive authorization from the villagers to sign the land transfer contract on their behalf. Second, the villager conference is convened in Jin’an Village to elect representatives, typically village cadres, who will serve as intermediaries between the investor, the Village Committee, and the villagers. Finally, the Village Committee and the investor sign a land transfer contract, in which the investor takes the lead in drafting the contract, while the committee focuses on negotiating the duration and price of the land lease. In this model, land transfer matters are negotiated by the Village Committee and the investor, rather than the villagers. The villagers are only required to collect the proceeds from land leasing. Villagers find it reassuring to entrust the land transfer work to village cadres, “We don't have the legal knowledge to read the contract. But we trust our elected representatives to sign the contracts on our behalf, and we are only responsible for collecting the rent.” As of 2014, external investors Zhengsen Company, Jumu Agricultural Company, and Jinri Agricultural Company collaborated with the Jin’an Village Committee to finalize land consolidation in Jin’an Village.

3.3.2. Second Phase: Delivery of Land Proceeds

The land consolidation project in Jin’an Village faced difficulties in 2016. During the first two years after signing the contract, due to the Village Committee collected two years of land rent from the investors in advance, and the villagers were able to receive the proceeds from the land transfer on time during these two years, most people were optimistic about the future development of the land consolidation project in the village. In 2016, due to the investor’s mistake in the pre-assessment of the agricultural project in Jin’an Village as well as the reduction of policy subsidies for external investors by the Yubei District Government, the investor in Jin’an Village was not able to realize a profit on the land transfer project and thus was unable to repay the land rent.

The investors’ delayed payment of rent incited dissatisfaction among the villagers, which in turn translated into their concern about the land transfer situation. In our interviews, we found that only a minority of villagers expressed satisfaction towards the present status of land transfer in the village, and their discontent largely stems from investors falling behind on rent owed for their land. The villagers complained, “How can they (referring the external investors) have money to continue running the company when they can’t even afford to pay rent for the land. If they don’t pay us rent, we won’t let them produce on the land.” (Interview with villager, 20230418) During the first phase of land consolidation, the villagers grant authorization to the Village Committee to sign the contract for transferring land to the investor. Therefore, in case of rental defaults, the villagers instinctively seek help from the Jin’an Village Committee.

In the face of the villagers’ request, the Jin’an Village Committee was caught in a dilemma. Consequently, village cadres were dispatched to negotiate with the investor regarding overdue land lease payments. During the first few communications, the investor requested assistance from the Village Committee in deferring land rent payments due to the villagers, citing cash flow challenges in the course of operation, and promised to provide the funds as soon as possible. When the village cadres delivered the investor’s response to the villagers, the villagers agreed to delay the investor’s rent payment based on their trust in the Village Committee. However, the investor failed to fulfill their promise and stopped paying the land rent to the villagers in 2016 without any justification. Since then, despite making repeated efforts to contact the investor, the village cadres have not achieved positive results. When the cadres relayed the status of their communication to the villagers, the villagers generally showed dissatisfaction, and even led to a division between the villagers and the village cadres in the villagers’ representative groups. One village representative said, “I am not like them (referring to village representatives with the status of village cadres), I am an ordinary villager and I have to represent the interests of the villagers. Now that the investors can’t pay the rent, I can’t be a yes-man like those village cadres, I have to find the investors to solve the problem.” (Interview with village representative, 20230418) The replies of the companies and village cadres were perceived by the villagers as a kind of deception, resulting in the trust problem of the villagers towards the Village Committee and village cadres. The villagers have requested that the Village Committee make public the contact information of the investors so that they can directly communicate with them. Based on our survey results, over 60% of the villagers involved in land transfer expressed their intention to reclaim land usage rights if the investor fails to pay the rent.

3.3.3. Final Result: Dissolution of the Contract through Litigation

The villagers’ strong dissatisfaction exerted pressure on the Village Committee, leading it to convene a villager conference to discuss the investors’ arrears in paying land rent. The villagers voiced discontent with the village officials at the conference, convinced that instead of fulfilling their promise to the villagers of “higher rents every year,” the village cadres had assisted the investors to delay the delivery of rents when the investors were in arrears, to the detriment of the interests of the villagers. In the face of the villagers’ questioning, the village cadres argued, “Firstly, the land consolidation in Jin’an Village is a productive project that promotes village’s economic development and boosts the residents’ earning potential. Secondly, while negotiating with the investors, the villagers witnessed their confidence in their capital reserves and management capabilities, and the investors paid the villagers a lump sum of two years’ land rent, which convinced everyone of the investors’ ability to pay the rent. Finally, it was the villagers who authorized the Village Committee to sign the land transfer contract with the investors, and the land rent was also paid directly to the villagers, and all the Village Committee could do was to pass on the information.” (Interview with village cadre, 20230419)The defense presented by the village cadres had minimal impact, and some members of the Village Committee were disqualified as cadres in this villager conference.

During the conference of Jin’an Village, all participants of the land transfer program were present to vote. Two solutions exist for the investor’s default on land rent: one is for the Village Committee to intervene and oblige the investors to find someone else to fulfill the land transfer contract within six months. The other is for the Village Committee can file a lawsuit in local court, demanding that the contract be terminated, the investors compensate the villagers for damages, and the land be restored to its pre-contract state. Because the investors in Jin’an Village had ceased communication with the villagers, the villagers no longer trusted the investors. After a vote by the villagers, the villager conference decided to hire the lawyers through the Village Committee to take legal action against the external investors. It is noteworthy that during pretrial preparations, the Village Committee is limited in its qualifications while carrying out litigation on behalf of the villagers: first of all, the lawyers can communicate directly with the villagers in order to comprehend their claims and examine relevant evidence documents. Secondly, lawyers can present matters concerning litigation at village meetings, without the Village Committee’s involvement. Thirdly, the Village Committee requires additional written authorization from the villagers for the disposition of certain specific rights, such as land replanting and re-demarcation of land boundaries. The villagers expressed satisfaction with the lawsuit preparations, saying, “It is reassuring to have lawyers in charge of the lawsuit. They (the lawyers) are more professional than the Village Committee, and they are more considerate to us and can fight for our greater interests in the litigation. The lawyers are highly detail-oriented and patiently respond to our queries. During my interaction with the lawyers, I realized the importance of knowing the law. I hope they will continue to give us help.” (Interview with villager, 20230419) Ultimately, in June 2018, the Village Committee filed a lawsuit against the Village’s external investors, alleging a breach of contract.

4. Discussion

Land consolidation is a vital aspect of China’s rural revitalization strategy now implemented nationwide. The case study of Jin’an Village illustrates how land consolidation facilitates the democratization of politics and the promotion of legal consciousness within rural communities. Additionally, it offers an insight into how economic development, political development and the rule of law are interrelated.

4.1. Internal Procedures have Enhanced the Level of Political Democratization

Land consolidation is frequently considered a program that can significantly enhance the economic productivity of farms [

33], and the land consolidation efforts in Jin’an Village support this viewpoint. As a means of fostering local economic growth, land consolidation in Jin’an Village has directly or indirectly helped in the democratization of community politics. Although the first phase of land consolidation was influenced by village cadres, the subsequent process demonstrated a remarkable progress of democratic politics in Jin’an Village.

First, the practice of transparent voting within the village promotes the democratization level in Jin’an Village. In a traditional community, trust and reciprocity based on kinship and friendship are the main forces influencing decisions on public affairs [

34,

35]. As a result, the Village Committee, which acted as the hub of the village’s social network, could usually make decisions on public affairs in the village without consulting all villagers. However, during the Jin’an Village land consolidation, the committee’s power waned when confronted with external investors who were not affiliated with the village. This is because the concentration of fragmented land is the transfer of the villagers’ land use rights to investors, the behavior by virtue of personality makes it impossible for the Village Committee to make choices on behalf of the villagers, and it can only obtain the villagers’ consent by convening a villager conference. Neubauer asserts that democratic politics require two essential elements: “communication among members of the political system” and “into the procedural norms of the system” to enable group with competing preferences to convene and negotiate [

36]. Jin’an Village convened the villager conference to discuss the transfer of land, with all community members encouraged to participate. Objective information was exchanged through the open delivery of information by village cadres and discussions among villagers during the conference, promoting the necessary communication for democratic decision making. Villagers directly express their political choices through voting [

37], the results of which express the public good recognized by the villagers [

38], and determine the direction of development of land consolidation in Jin’an Village.

Secondly, the criticism of village cadres by the villagers during land consolidation setbacks also evidence of an enhanced sense of democracy among the Jin’an villagers. Village cadres conform to the typical profile of local elites [

39], who attain higher levels of influence through commanding greater social networks and human capital [

40]. In the first phase of land consolidation in Jin’an Village, the village cadres were the first to understand and grasp the land consolidation policies and procedures. This together with the cadre status granted to them by the Village Committee ultimately formed the advantage of the village cadres in the process of dialoguing with the villagers [

41]. When the villagers authorized the village cadres to carry out the acts of information liaison, external negotiation and contract signing for the land transfer, these cadres actually gained a decisive role in dominating the land consolidation work in Jin’an Village [

32]. This situation raises concerns regarding a potential divide between village cadres and villagers, where elites in position of power would unequally distribute the benefits of rural reform to themselves [

42,

43]. The survey results from Jin’an Village revealed that while there were no conflicts regarding benefit distribution, there were substantial differences in perspectives between villagers and village cadres in the face of the failure of land consolidation. This created a sense of “welfare is violated by socio-political elites” among the villagers [

44]. Disgruntled villagers contribute to the convening of the villager conference, the villagers’ criticism and the defense of the village cadres throughout the conference constitute a proceduralized idea of popular sovereignty [

45], and the use of voting by villagers to determine the removal of village cadres underscores the centrality of voting in consultative democracy and its ability to curtail power. In summary, land consolidation aimed at improving the local economic development, regardless of its success or failure, will directly or indirectly promote the level of local political democratization.

4.2. External Measures have Enhanced the Villagers’ Legal Consciousness

Like the mainstream land consolidation approach, land consolidation in Jin’an Village is based on contracts under the influence of market factors. However, unlike the traditional process of individual transactions, land consolidation in Jin’an Village includes a first phase of authorization and negotiation, and a second phase of legal action. The results of the land consolidation process are established through legal instruments, which may lower transaction costs and enhance trust in the security of property rights within the process of land consolidation [

46].

During the first phase of land consolidation in Jin’an Village, the signing of contracts was central to the process, indicating that the concept of property rights has become a general consensus in the village. Typically, contracts serve to protect property rights [

47], which in turn has been shown to have a decisive impact on economic growth [

48]. Our survey found that there were two kinds of contracts in the initial phase of the land consolidation process: authorization contracts and land transfer contracts. Villagers need to issue authorization contracts to the Village Committee, as Jin’an villagers are not well educated and most are elderly, they are unable to negotiate effectively with outside investors. In addition, individual land transactions in areas of land fragmentation have proved to be extremely costly and can cause the land market to become less active [

49]. The decision by the villagers to sign an authorization contract with the Village Committee can serve a dual purpose. On the one hand, it can enable the Village Committee to fully utilize their advantages in collecting information and their social capital, which in turn can result in greater benefits in external negotiations [

50,

51]; on the other hand, such a contract can prove that the villagers have the legal rights to use the land and protect their property rights to the land [

52]. The land transfer contract is the result of negotiations between the Village Committee and the investors. North considers securing rights in property are the key to sustained economic growth [

53]. By establishing a land transfer contract that covers the rights and obligations of the participants, including the rent of the land and the duration of the lease, property rights can be protected by a formalized system of transferable ownership, which increases the certainty of the property [

54]. Whether investors or villagers, a secure system of property rights trading increases investment willingness, leading to enhanced economic development. Furthermore, the fact that Jin’an villagers chose to sign the land transfer contract in a democratic process demonstrates that they, like investors, have confidence in China’s legal system [

55].

In the second phase of land consolidation, the approach of Jin’an villagers in responding to the breach of contract by the external investor is another proof of the villagers’ heightened legal awareness. After the contract was signed, the villagers demonstrated a clear tendency to maintain the contract survival, even if the investors’ failure to pay the rent. Instead of terminating the contract immediately, the villagers actively contacted the investors through the Village Committee and agreed to a rent delivery delay. The behavior of the villagers indicates that they would like to see the investors continue to fulfill their contracts after they have overcome the difficulties, as the continuation of those contracts could contribute to the economic development of the village [

47]. Even after the investors indicated their intent to cease payment of rent to the villagers, the villagers did not respond with unlawful retaliation but instead brought the dispute to court, expressing their dissatisfaction through the appropriate legal channels. Daniels asserts that access to justice is a crucial prerequisite for safeguarding property rights [

56]. The villagers of Jin’an Village exemplify this notion by consciously choosing to resolve disputes and defend their property rights through an open and legal system. The case of Jin’an Village illustrates that once the conventional economic model centered on clanship is dismantled, and the law and institution become the foundation of the local economic framework, the villagers of Jin’an Village will develop a strong sense of legal consciousness.

4.3. Methodological Limitations and Future Research Directions

Limitations of this study include the following. First, it is difficult for a single case study to represent the vast and varied patterns of development exhibited in rural China. In addition, our case focuses on the actual operation of the rural land consolidation process, and thus may diverge from the ideal state of rural policy design. While our discussion provides an analytical paradigm for comprehending the correlation between land consolidation and democratic politics and legal consciousness, it is crucial to consider specific geographical and historical contexts when examining these interrelationships. In order to be able to do so, further comparative research on the status of land transfers in different region are needed.

Second, our qualitative case study had to rely on policy documents and local interviews to do so. These limited sources do provide us key insights into the relationship between rural land consolidation, democratic politics, and the rule of law. However, these sources refer only to external investors, village members, and omit the government, which wields the greatest influence in China. We particularly look forward to future studies will regard local governments as active participants in land consolidation and to development a framework for analyzing the association between governments, investors, and villages.

5. Conclusions

This paper takes a political economy approach to investigate the impact of land consolidation on the politics and concept of the rule of law in local societies when it is used to promote economic development in rural China. The case study of Jin’an Village in Dawan town verified and answered the standpoint that were raised in this paper. Land consolidation has contributed to the political democratization and legal consciousness of the countryside through the introduction of external investors and the marketization of land use rights. A general conclusion is that, regardless of the final outcome of a land consolidation project, as long as land consolidation is carried out on the ground, the people’s sense of modernization, with democracy and the rule of law at its core, will be enhanced.

We identified two perspectives for observing the specific process of land consolidation: the processual perspective and the relational perspective of participating members. The former examines the process of land consolidation, while the latter focuses on the relationships between the involved members. From the procedural perspective, the first phase of land consolidation is concerned with democratic decision-making procedures and the signing of contracts to protect property rights; the second phase revolves around the criticism of traditional political elites (village cadres) and judicial proceedings. From a relational perspective among participants within the village, the villagers have emerged as a new political force, replacing the traditional political elites represented by village cadres and taking charge of the decision-making process for public affairs. The villager conference becomes the sole decision-making body for public affairs; when confronted with external investors, the villagers prioritize safeguarding their property and obtaining anticipated returns. Accordingly, they opt for signing contracts and pursuing legal action in court. In brief, both perspectives affirm the conclusions of our previously mentioned study that land consolidation in rural China fosters local political democratization and legal consciousness.

Although this was an area-specific study representing only the rural areas of Chongqing, China, our findings provide insights into achieving sustainable democratic politics and legal consciousness development from an economic development perspective. We hereby propose the following policy recommendations based on our study:

The focus should remain on promoting rural land consolidation projects and stimulating rural economic growth. It is important to aid villagers in developing fresh social capital and to design models for rural land transfer, including the setup of cooperative organizations that can be managed by villagers themselves.

Improving villagers’ motivation to participate in the decision-making process of public affairs, enhancing their ability to access information and negotiate effectively, innovating negotiation models for land consolidation, and promote their leadership roles in the land transfer processes.

Strengthening the capacity of communities to provide professional services to farmers in accordance with the needs of land consolidation, for example, by having lawyers provide legal services to farmers in the process of land transfer.

Strengthening investor qualification screening. The government conducts a rigorous assessment of external investors’ qualifications and excludes those who do not meet the qualification requirements from land consolidation projects by setting open qualification conditions. Furthermore, the local villagers’ feedback on the investors can be used as an evaluation indicator for the government decide whether to provide policy support to the investors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.D., S.X. and B.C.; methodology, Q.D.; field investigation, Q.D., S.X.; writing-original draft preparation, Q.D., S.X. and B.C.; tables and images, Q.D.; supervision, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the interviewees who participated in the fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lin, G.C.; Yi, F. Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geography 2011, 32, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X.; Liu, W.Y. The Formation and Governance Path of China’s Rural Hollowing. Academic Journal of Zhongzhou 2012, 5, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Chen, Q.; He, Y.; Xu, D. Spatial–Temporal Features and Correlation Studies of County Rural Hollowing in Sichuan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, P. J., & Kefalas, M. J. (2009). Hollowing out the middle: The rural brain drain and what it means for America. Beacon press.

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D. Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land use policy 2016, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.S.; Guo, L.Y.; Li, Y.H. Spatial-temporal characteristics for rural hollowing and cultivated land use intensive degree: Taking the Circum-Bohai Sea region in China as an example. Progress in Geography 2013, 32, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Li, W.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, R. Multifunctionality assessment of the land use system in rural residential areas: Confronting land use supply with rural sustainability demand. Journal of environmental management 2019, 231, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.; King, R. Land fragmentation and consolidation in Cyprus: A descriptive evaluation. Agricultural Administration 1982, 11, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Z. Productivity and efficiency of individual farms in Poland: a case for land consolidation: Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the American Agricultural Economics Association. Long Beach, CA 2001, 2, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Janus, J.; Glowacka, A.; Bozek, P. (2016, May). Identification of areas with unfavorable agriculture development conditions in terms of shape and size of parcels with example of Southern Poland. In Proceedings of 15th International Scientific Conference: Engineering for Rural Development (Vol. 15, pp. 1260–1265).

- Vitikainen, A. An overview of land consolidation in Europe. Nordic Journal of Surveying and real Estate research 2004, 1, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. (2004). ( Rome, 37.

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Carletto, C. Land fragmentation, cropland abandonment, and land market operation in Albania. World Development 2012, 40, 2108–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lu, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, F. Developing planning measures to preserve farmland: a case study from China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13011–13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, R.; Forrest, R. Elevating the peasants into high-rise apartments: The land bill system in Chongqing as a solution for land conflicts in China? Journal of Rural Studies 2016, 47, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Zhou, G.; Qiao, W.; Yang, M. Land use transition and rural spatial governance: Mechanism, framework and perspectives. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2020, 30, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Ives, C.D.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. Modes and practices of rural vitalisation promoted by land consolidation in a rapidly urbanising China: A perspective of multifunctionality. Habitat International 2022, 121, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Promotion of degraded land consolidation to rural poverty alleviation in the agro-pastoral transition zone of northern China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation boosting poverty alleviation in China: Theory and practice. Land use policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; Qu, L. Effect of land-centered urbanization on rural development: A regional analysis in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Urban–rural transformation in relation to cultivated land conversion in China: Implications for optimizing land use and balanced regional development. Land use policy 2015, 47, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mo, Z.; Peng, Y.; Skitmore, M. Market-driven land nationalization in China: A new system for the capitalization of rural homesteads. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.T.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at village level: A case study of a Chinese village. Journal of Rural Studies 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao Runling. (2013). Chengxiang Jianshe Yongdi zengjian Guagou yu Tudi Zhengzhi: Zhengce he Shijian [The Policy and Practice of Land Management]. Beijing: Zhongguo Fazhan Chubanshe, 209-213.

- Liu, Y.; Qiao, J.; Xiao, J.; Han, D.; Pan, T. Evaluation of the effectiveness of rural revitalization and an improvement path: a typical old revolutionary cultural area as an example. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. (2006). Understanding the process of economic change. STORIA DEL PENSIERO ECONOMICO, (2005/2).

- Barro, R.J. Democracy and growth. Journal of economic growth 1996, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J. (2017). Testing the limits to the “rule of law”: Commercial regulation in Vietnam. In Commercial Law in East Asia (pp. 95-122). Routledge.

- Bromley, D.W. 1989. Economic Interests and Institutions: The Conceptual Foundations of Public Policy. Basil Blackwell, New York, USA.

- Zhang, Y.; Westlund, H.; Klaesson, J. Report from a Chinese Village 2019: Rural homestead transfer and rural vitalization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P. Applying evaluation criteria for the land consolidation effect to three contrasting study areas in the Czech Republic. Land use policy 2006, 23, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.L. (2007). Accountability without democracy: Solidary groups and public goods provision in rural China. Cambridge University Press.

- Wong, C. The fiscal stimulus programme and public governance issues in China. OECD Journal on Budgeting 2011, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, D.E. Some conditions of democracy. American Political Science Review 1967, 61, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.E.; Birdsall, J.H.; Ciesluk, S.; Garlett, L.M.; Hermias, J.J.; Mendenhall, E.; Schmid, P.D.; Wong, W.H. Voting counts: Participation in the measurement of democracy. Studies in Comparative International Development 2006, 41, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, T. Voting and democracy. Canadian journal of philosophy 1995, 25, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Develtere, P. New co-operatives in China: why they break away from orthodox co-operatives? Social Enterprise Journal 2010, 6, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Beard, V. A. Community driven development, collective action and elite capture in Indonesia. Development and change 2007, 38, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platteau, J.P.; Gaspart, F. The risk of resource misappropriation in community-driven development. World development 2003, 31, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Community-based and-driven development: A critical review. The World Bank Research Observer 2004, 19, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Jensen, M.; Nathan, I.; Treue, T. Beyond elite capture? Community-based natural resource management and power in Mohammed Nagar village, Andhra Pradesh, India. Environmental Conservation 2010, 37, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroska, A. Prawicowy populizm a eurosceptycyzm (na przykładzie Listy Pima Fortuyna w Holandii i Ligi Polskich Rodzin w Polsce), Wrocław 2010. Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis, (3230).

- Chambers, S. Democracy and constitutional reform: Deliberative versus populist constitutionalism. Philosophy & Social Criticism 2019, 45, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Janus, J.; Markuszewska, I. Land consolidation–A great need to improve effectiveness. A case study from Poland. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furubotn, E.G.; Pejovich, S. Property rights and economic theory: a survey of recent literature. Journal of economic literature 1972, 10, 1137–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J. A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American economic review 2001, 91, 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T. Complications for traditional land consolidation in Central Europe. Geoforum 2007, 38, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.Y.; Zhou, Y. Effectiveness and influencing factors of China’s targeted poverty alleviation and village assistance work. Geographical Research. 2020, 39, 1128–1138, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ito, J.; Bao, Z.; Ni, J. Land rental development via institutional innovation in rural Jiangsu, China. Food Policy 2016, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1981). Structure and Change in Economic History. New York: WW Norton.

- Von Mehren, P.; Sawers, T. Revitalizing the law and development movement: a case study of title in Thailand. HARVARD INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL 1992, 33, 67–102. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, G.S. The political economy of the rule of law in China. Hastings Business Law Journal 2009, 5, 309–354. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, R.J.; Trebilcock, M. The political economy of rule of law reform in developing countries. Michigan Journal of International Law 2004, 26, 99–140. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).