1. Introduction

The last few decades have uncovered increasing evidence that socioeconomic factors such as education, income, and occupation are key contributors to differences in the health status of different groups [

1](P. Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014). Low socioeconomic status is consistently associated with poor health and mortality outcomes for most groups, yet scholars have long sought to explain why this relationship appears to be distorted among immigrants, particularly those of Latin-American descent [

2](Kaufman & Cooper, 2008). Immigrants tend to have better health and mortality outcomes than their non-immigrant socio-economic counterparts, yet the “protection” found among immigrants appears to decline in subsequent generations greater lengths of stay in the United States [

3,

4](Teruya & Bazargan-Hejazi, 2013; Marks, Ejesi, & García Coll, 2014).

Multiple explanations have been put forth to explain the “immigrant paradox.” Many studies point to the role of acculturation on immigrants based on their generational status and length of stay in this country [

5](Zhang et al., 2012). These studies often rely on secondary data collected by national health surveys [

6,

7](Guarini et al., 2015; Lariscy, 2011), and typically rely on comparisons across simple measures of race/ethnicity or immigrant generation (as a proxy for acculturation) [

8,

9](Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2005; E. R. Hamilton et al., 2011). Due to the limitations in data collected within national or regional surveys, however, a reliance on secondary data offers limited knowledge about socioeconomic status beyond education or income. This offers limited insight into the complex ways in which immigrants navigate their political, economic and social barriers and how this influences their health.

Social networks are important determinants of immigration flows and play a key role in social capital, which can include knowledge about how to navigate health care services [

10](Waters & Jiménez, 2005). However, public health models broadly position “social determinants of health” as the broad set of nonmedical factors that can influence health, categorizing these along several lines including that of proximity to determinants at earlier points along causal pathways (upstream)—for example, polluted water as upstream to drinking contaminated water as downstream [

11](P. Braveman et al., 2011). This shapes recommendations by creating a unidirectional focus on individual-level changes in behaviors/knowledge/attitudes, in contrast to influencing the mechanisms through which public policies, organizational practices and social structures shape access to health-promoting resources. This framework is consistent with Svendsen and Svenden’s “troika” of social capital being examined through political science, economics, and sociology [

12](J. M. Halstead & Deller, 2015).

Despite multiple cries for more nuanced and relevant measures of SES for health research that respond to the differences in groups that vary based on race/ethnicity and other factors [

13,

14](Braveman et al, 2005; Shavers, 2007), no study has yet presented a framework for measuring SES in in minoritized immigrant populations. The lack of attention to SES is particularly problematic in health research involving minority immigrant populations. Structurally, these populations are more alienated from the native-born and White majorities [

15](Kao, 2004). However, immigration status is rarely measured directly due to legal and ethical considerations. Without factoring in economic resources acquired through social capital, it is unclear whether existing measures have the capacity to (a) make accurate comparisons between the SES of immigrants and their native-born counterparts, and (b) capture the mechanisms through which SES impacts immigrant health. This paper sets out to explore SES and social capital among migrants.

2. Socioeconomic Status

Reviews of widely used measures of SES in health research documented a wide range of measurement tools [

13,

16](Andersson, 2015; P. A. Braveman et al., 2005). While most health studies tend to measure SES utilizing a single socioeconomic variable such as income, wealth, education, or occupation, some use composite indices measures or scales constructed from two or more variables or complex questionnaires with multiple domains [

14,

16](Andersson, 2015; Shavers, 2007). These measures are utilized inconsistently across different countries—for example, occupation is used most frequently in Europe and rarely used in the United States, despite significant evidence pointing to the relationship between occupational grade and health [

1,

18](Psaki et al., 2014; Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014). The inconsistency of measures used in both national and cross- national health research creates unique challenges in documenting the comparative health status of different groups.

Health researchers have generally measured SES in objective terms, yet a growing interest in the impact of subjective social status has led to a proliferation of studies focused on subjective measures of socioeconomic status. Cross-national studies have produced evidence that subjective SES measures are significantly related to measures of health and well-being [

19](Präg et al., 2016). However, subjective SES is unable to explain cross-national variation in health disparities and individuals from different countries vary in their self-definition of socioeconomic status across time [

16](Andersson, 2015). Most studies tend to measure SES at a single point in time [

20](Dinwiddie et al., 2014), overlooking the significant influence of past socioeconomic experiences such as parental education [

6](Guarini, 2015).

Inconsistencies in the definition, conceptualization, and measurement of SES are further aggravated by the confounding of race and socioeconomic status. Significant variation exists in net worth and job status of different racial/ethnic groups, yet both race and socioeconomic status are independent predictors of health status [

21](LaVeist, 2005). This may be, in part, due to key differences in the physical, social or service environments of a person’s neighborhood, which in turn leads to a differential impact on socioeconomic opportunities [

13](P. A. Braveman et al., 2005). Latin-Americans, despite their general classification as an ethnic, cultural and legal group, also experience different health outcomes depending on their socially assigned race, with studies identifying a “White advantage” in health status for those who consider themselves Hispanic but are socially considered to be White [

22](Vargas et al., 2014).

As noted, socioeconomic status can be conceptualized and measured in multiple ways, which has led to significant inconsistencies in the definitions, variables and tools used in health disparities research. Experts disagree on the utility of objective and subjective measures as well as the applicability of these measures in comparative research on different racial/ethnic groups. It has also been noted that different dimensions of socioeconomic status (e.g., occupation, income and education) can manifest themselves in different ways among immigrant groups, largely part due to the influence of social capital. This suggests that the causal pathway between socioeconomic status and the health of immigrants differs from that of their U.S.-born counterparts. Based on this evidence, it seems reasonable to consider how social capital could be factored into measures of socioeconomic status for immigrants.

3. Immigration Status

Immigration status has a significant influence on the accumulation of human capital, the combination of knowledge, experience, skills and competencies that a person develops throughout their life and translates into economic value, regardless of whether it is acquired formally or informally. This occurs through U.S. institutions that regulate and impact access to political, economic, and social resources: social policy, immigration policy and labor policy. In contrast to undocumented immigrants, immigrants with lawful status (e.g., naturalized U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, people with DACA) possess a political and legal identity that provides greater access to U.S.-based institutions in sectors such as education, finance, and labor. Through their access to U.S. institutions critical to the development of human capital such as universities, employment, and financial credit systems, immigrants with lawful status may have higher opportunity to acquire higher education, financial services, wage-earning income, childcare, and transportation, all of which translate to economic value in the formal U.S. economy (formal human capital).

Immigrants that lack access to U.S. institutions for education, income and labor still must live in an economy in which healthcare is very restricted for those that don’t have lawful access. Immigrants without lawful status are less likely to acquire formal human capital through higher education, financial services, wage-earning income, and personal loans. This, in turn, limits their household’s ability to access human capital resources in the formal economy, such as vocational training, wage employment, licensed childcare providers, or mortgage and car loans and other forms of credit. However, coethnic immigrant communities are not homogenous. Within their own communities, immigrants possess varying levels of human capital and social capital upon arrival in the United States. This can include political and economic resources such as fluency upon arrival, family members with lawful status already present in the United States, age upon arrival, higher education of family members in host country, prior training in a trade, education upon arrival, length of time in country, or location of formal education [

23,

24,

25](Edberg et al., 2011; M. Li, 2016; Lim & Morshed, 2019). Collectively, these resources can translate into social networks that provide differential access to U.S. institutions as well as informal human capital.

4. Social Capital and Human Capital

Immigration status has a significant influence on the accumulation of human capital, the combination of knowledge, experience, skills and competencies that a person develops throughout their life and translates into economic value, regardless of whether it is acquired formally or informally. This occurs through U.S. institutions that regulate and impact access to political, economic, and social resources: social policy, immigration policy and labor policy. In contrast to undocumented immigrants, immigrants with lawful status (e.g., naturalized U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, people with DACA) possess a political and legal identity that provides greater access to U.S.-based institutions in sectors such as education, finance, and labor. Through their access to U.S. institutions critical to the development of human capital such as universities, employment, and financial credit systems, immigrants with lawful status may have higher opportunity to acquire higher education, financial services, wage-earning income, childcare, and transportation, all of which translate to economic value in the formal U.S. economy (formal human capital).

4.1. Social Capital and Employment

Through their social support networks, immigrants can significantly shape occupational status by sharing information such as job opportunities, transportation, or living arrangements [

26](Garip, 2008). Immigrants frequently engage in entrepreneurial activities within their co-ethnic communities [

27](Kesler & Hout, 2010), creating ethnic and linguistic niches with strong occupational concentration [

28,

29](Liu & van Holm, 2019; Mouw & Chavez, 2012). Within these spaces, families provide an inexpensive labor pool and financial resources to enable the development of small businesses and employment opportunities [

30](J. M. Sanders & Nee, 1996). Immigrant networks can also share information on how to register their business as a trade name (Doing Business As, or DBA), which permits them to conduct business under a different identity from their own personal name and secure a federal tax ID number to comply with applicable tax guidelines [

31](Matthews & Liguori, 2021).

Immigrants with lawful status still form a significant proportion of laborers in higher-risk work such as construction, agricultural and day labor [

32](Díaz Fuentes et al., 2016). Reasons for unemployment may vary as well, since longer unemployment durations may be associated with lower community trust [

33,

34](Keita & Valette, 2019; Morales, 2016), while self-employment in the informal economy is often associated with higher job satisfaction [

35](Binder & Coad, 2016).

Employees in the formal economy often make a trade-off between job security and occupational safety [

32](Díaz Fuentes et al., 2016). Immigrants also contribute to day labor markets in urban areas, an economic adaptation that has been largely unexplored but likely carried over from seasonal agricultural work in their countries of origin [

36](Valenzuela, 2003). Further, while immigrants tend to occupy positions associated with lower social status than the native-born, social capital has been shown to have a positive effect on the knowledge and skills that they bring to their occupation [

30](Sanders, 1996). Evidence suggests that social support can even enhance the protective effects of health insurance, leading to better health outcomes for insured family members and contributing to overall family health [

37](Richter et al., 2015).

4.2. Social Capital and Income

Studies reveal that social capital is similar to income or wealth in its impact on the health of immigrants [

38](OECD & IRDES, 2010). Viewed as interdependent collective economies, immigrant social networks can mitigate the impact of lower incomes and reduce reliance on services in the formal market economy, depending instead on social networks for services such as childcare [

39](Ryan, 2011), [

40]carpooling (Barajas, 2021), and peer lending [

41](Kear, 2016). Among immigrants, income produced outside of the formal labor market is a significant share of total household income, while conventional measures tend to assume one job per worker and often obscure labor or self-employment in the informal economy [

42](Tienda & Raijman, 2000). Existing measures of household income in national data sources are therefore likely to underestimate the income of many immigrant families [

27](Kesler & Hout, 2010).

4.3. Social Capital and Education

Education is often used as a proxy for social status [

17](Braveman et al, 2011), yet this assumes that similar levels of education exert an equal influence on the social status of different groups. However, opportunities for educational attainment vary significantly across different countries. For example, a person who completes compulsory government education in Mexico would reach an education equivalent to the U.S. version of 9th grade, yet still be considered to have completed their basic education [

43](Schwellnus, 2009). This could reasonably lead to a different set of social relationships and subjective social status than their U.S educational counterparts. Others point to the fact that education helps individuals develop skills through which they can grow their social networks [

38](OECD & IRDES, 2010), and evidence suggests that the increase in earnings associated with immigrant educational programs is higher than that of comparable natives [

44](Ferrer & Riddell, 2008). Immigrants with less formal education also tend to be more receptive than non-immigrants to information from informal sources as their peer networks, radio, and television [

45](Clayman et al., 2010), all of which point to potentially different pathways through which education impacts health.

Understanding how social capital influences the relationship between education and health is also key to a more nuanced understanding of immigrant health. While social capital may contribute directly to the educational outcomes of immigrant youth [

15](Kao, 2004), its impact on immigrant health may be a result of its influence on social status and knowledge dissemination. By relying on their social networks for information, immigrants may reduce their dependence on formal knowledge acquired through the educational system. Immigrants may also experience a higher degree of education-related social status among their peers than they would among the native-born, which might influence their health in a manner similar to measures of subjective social standing. A measure of socioeconomic status that accounted for differences in experiences of education might therefore seek to apply a weighted system that accounted for subjective social status and health-information-seeking behavior.

5. Nature of Social capital

Recent migrants are highly dependent on resources acquired through their social networks rather than through a market economy of exchange based on income [

46](O’Doherty et al., 2017). This larger web of relationships, characterized by mutual obligations and expectations, information channels and social norms, collectively generates value defined as social capital [

15](Kao, 2004). Bordieu advanced the idea that social exchanges should be considered beyond a self-interested conceptualization, but also examined for their economic value, concluding that social exchanges should be included in ideas of “capital and all their forms” [

46](Bourdieu, 1987).

Scholars disagree on the individual and collective nature of social capital [

47,

48](Hilfinger Messias et al., 2015), (Keeley, 2007), its dimensions [

49](Pinxten & Lievens, 2014), and its measurement (Glaeser et al., 2002). Despite these areas of disagreement, studies have consistently identified social capital as a protective mechanism that influences various health outcomes [

51,

52,

53,

54](Miller et al., 2006; Pevalin & Rose, 2003; Szreter & Woolcock, 2004b) (O’Doherty et al., 2017). At the same time, most assume that social capital exerts a positive influence on health [

55](Moore & Kawachi, 2017), while recent evidence suggests the possibility of a negative relationship between social capital and health (i.e., exchanging wrong information or promoting unhealthy behaviors) [

54](O’Doherty et al., 2017). Empirically, this means that social capital must be defined in a way that permits for both positive and negative relationships to emerge.

Some note that that social capital can be episodic and potentially harmful, urging caution when considering policy recommendations based on this concept [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60](Cheong et al., 2007; Villalonga-Olives & Kawachi, 2017). (Gericke et al., 2018; Peterson & Crittenden, 2020; Tegegne, 2016). Programs designed to improve social capital may have an influence on health, but without taking into consideration the broader structural factors that contribute to the health of immigrants, they are unlikely to make a significant impact on health inequities. In a practical sense, a positioning of social capital as an individual, rather than collective, property allows for the creation of aggregate measures that can be subsequently explored alongside community-level indicators such as city, county or state policy indicators of healthcare access, political opinion, etc. [

58,

59,

60](Gericke et al., 2018; Peterson & Crittenden, 2020; Tegegne, Given the abundance of definitions of social capital, it is important to clearly delineate the most appropriate concept to include in a framework of the impact of socioeconomic status and social capital on immigrant health [

48](Keeley, 2007).

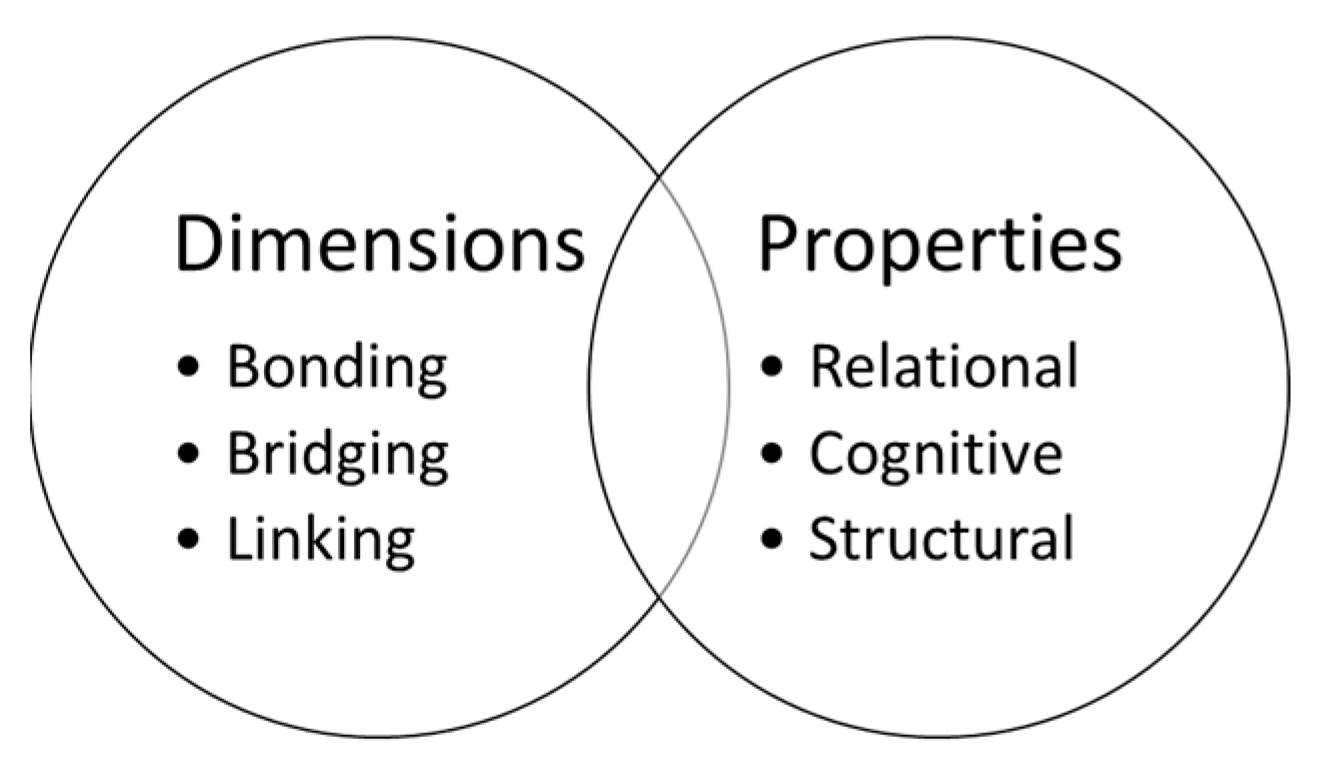

5.1. Dimensions of Social Capital

Social capital is conceptualized across three different dimensions: bridging, linking, and linking. The distinction is based on the degree of homogeneity between individuals connected through social networks in terms of their social identity and position in the social hierarchy [

61](Johnson et al., 2017).

5.1.1. Bridging Social Capital

Through their education, labor, and income-generating activities in the formal economy, immigrants with lawful status develop social ties with diverse groups and individuals outside of their immediate neighborhood or coethnic community (bridging social capital) [

61](Johnson et al., 2017). Bridging social capital is captured by heterogeneity across social identities and is inclusive of community-based organizations within neighborhoods such as churches, social services organizations, and schools. Immigrants with higher levels of bridging social capital--such as direct relationships with employers, U.S.-born children with knowledge of the educational system, or membership in social networks with members across different professions--can leverage these relationships for coethnic community members. However, immigrants with high levels of bridging social capital may be more likely to socialize within social networks generated through their education or employment rather than their coethnic communities, thus limiting their reliance on bonding social capital for access to health-promoting resources [

62,

63,

64](Danes et al., 2009; Iwase et al., 2012; Lancee, 2016).

5.1.2. Linking Social Capital

Immigrants can also develop linking social capital, social ties with institutional agents that are well-positioned to provide key forms of social and institutional support across diverse networks, organizational and community settings [

65](Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Linking social capital is characterized by vertical relationships within the social hierarchy, including law enforcement and government officials at local, state and federal levels [

66](Carrillo- Álvarez et al., 2019).

5.1.3. Bonding Social Capital

Bonding social capital is characterized by homogeneity in social identity across race/ethnicity, social and economic levels, etc., to include friends, family members, neighbors, and coworkers. Social networks, particularly relationships among peers within immigrant communities, become a critical way of for immigrants to access resources outside of the formal economy. These resources, which occur without the confines of significant regulation by U.S. political and economic institutions, may include informal work training, entrepreneurial activities, non-wage employment in coethnic businesses [

66](Raijman & Tienda, 2000), inter-personal loans, and family-based childcare and transportation (informal human capital). In contrast to immigrants who rely on formal human capital to access resources in the formal economy, immigrants with reduced access to U.S. institutions are much more reliant on their intimate social networks to acquire informal human capital.

Immigrants with lower levels of human capital may be more reliant on their coethnic networks for health-maintaining resources. With less access to resources in the formal economy, these immigrants may also turn to unregulated forms of health care, such as community-based alternative medicine providers and medications without a prescription. Social networks among immigrants at lower socioeconomic levels relative to their coethnic communities can reinforce barriers to health such as a distrust of healthcare system, limited knowledge of healthy lifestyle choices, or negative attitudes about the value of preventive care [

67,

68](Jenkins et al., 1996; Vargas Bustamante et al., 2010). Over time, this can impact health as inadequate responses to emerging health needs outweigh the positive health of impact of psychological support or access to economic resources.

Scholars have also pointed a tendency to idealize the role of social capital for migrants without expanding on its various properties or potentially harmful impacts. For example, refugees that access employment through bridging social capital are more likely to secure high- skilled employment opportunities than those who obtain employment through bonding social capital, which often leads to low-skilled work or underemployment [

57,

69](Horak et al., 2020; Villalonga-Olives & Kawachi, 2017). Immigrants may also have family members reliant on their remittances, particularly if these are older adults or individuals with high levels of health care. This may create additional economic and psychological stress, particularly in times of family illness as immigration status or minimal access to human capital can minimize their ability to provide more direct support [

70](Newman et al., 2018).

5.2. Properties of Social Capital

Social capital is also distinguished across its various properties: relational, cognitive, and structural. Relational social capital refers to direct relationships with individuals that can provide economic or social support [

34](Morales, 2016). Cognitive refers to shared understandings, values and norms including general trust [

61](Johnson et al., 2017). Finally, structural refers to participation in formal social networks, associations, and other forms of social, civic, or political engagement. Cumulatively, these properties of social capital can be shared or obtained through different social mechanisms--for example, relationships with individuals embedded in healthcare organizations, social interactions that generate implicit knowledge of how to navigate the healthcare system, and networks that yield access to exercise facilities or healthy food resources [

71](Parvanov & Petkova, 2019).

While social capital can be measured at both individual and collective levels, aggregate- level data must reflect categorizations that are reflective of community identities (e.g., distinctions in ethnic composition of neighborhoods) rather than bureaucratic categories such as zip codes or administrative regions. A conceptual framework for measurement of individual- level social capital is presented in

Figure 1. In keeping with other approaches, this conceptual framework recognizes uncertainty as a norm, focusing social capital as a dynamic process that is embedded within specific social and institutional environments, and therefore cannot simply be measured as an individual trait or as an “essentialist” concept [

72](Keck & Sakdapolrak, 2013).

6. Social Capital and Other Social Determinants of Health

Beyond socioeconomic status and social capital, the healthcare access of recently arrived immigrants to the United States is shaped by many components. In addition to federally-defined immigration and social statutes, state and local policies and organizational practices shape structural access to housing, childcare, transportation, healthcare, and health insurance.

Community attitudes may reflect ideas about immigrant worthiness for receiving healthcare services, healthcare as a reason or incentive for immigration [

73](Pourat et al., 2014), or the responsibilities of federal vs local governments to provide health care [

74](Viladrich, 2012). This may also tie into ideas of religiosity [

75](Modell & Kardia, 2020), and community knowledge about the effects of immigration on the economic well-being of the native-born [

76](Adler et al., 1994).

At the individual level, health behaviors can also contribute to poor health through inactivity and poor nutrition and frequent use of tobacco [

77](Pampel et al., 2010), alcohol [

78](Warner et al., 2010), and other illegal or unauthorized substances. Broadly, these components translate into scopes of practice that align with multi-level community health promotion efforts driven by theoretical frameworks such as the social-ecological model of health promotion or practice-driven frameworks such as the Spectrum of Prevention [

79,

80,

81](Barnard, 2020; Cohen & Swift, 1999; Fitzsimons, 2017).

7. Conclusions

This paper asserts that it is possible to develop a measure of socioeconomic status that accounts for the influence of social capital on immigrant health. The utility of such a measure lies in its ability to predict key health outcomes and, in doing so, to bring a new perspective to the highly-contested immigrant paradox that describes immigrants with better health outcomes than their native-born counterparts, despite what appears to be a lower socioeconomic status. In many ways, efforts to develop a more comprehensive measures of SES efforts mirror the recent development of the U.S. Census’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, a process created under the Obama Administration to provide a more complex and nuanced picture of a family’s assets and expenses than the Federal Poverty Line alone could provide [

82](Census Bureau, 2019). A more sophisticated measure of SES could allow researchers to reconsider their understanding of the immigrant paradox and the literature that seeks to explain its existence. While this paper does not make the claim that the immigrant paradox does not exist, it presents a clear argument that current measures of socioeconomic status are not as reliable among immigrant groups than among the native-born, and points to possible pathways through which these differences could be captured.

Even with a comprehensive review of the literature that maps out the breadth of social capital and its relationship to socioeconomic status and immigrant health, it is no easy task to sort through these varied mechanisms to identify the most appropriate ones to include in a more robust, theoretically-grounded measure of socioeconomic status. Such a process necessitates operationalization of these concepts into quantifiable variables, integrating them with existing measures of SES, and piloting new measures among immigrant groups.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Richard Scotch for his mentorship and review throughout various iterations of the ideas in this manuscript. I am also grateful to Jennifer Holmes, Jonas Bunte, and Sheryl Skaggs for their review of this content as presented in my doctoral dissertation.

References

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Reports 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J.S.; Cooper, R.S. Race in Epidemiology: New Tools, Old Problems. Annals of Epidemiology 2008, 18, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teruya, S.A.; Bazargan-Hejazi, S. The Immigrant and Hispanic Paradoxes: A Systematic Review of Their Predictions and Effects. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2013, 35, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, A.K.; Ejesi, K.; García Coll, C. Understanding the U.S. Immigrant Paradox in Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives 2014, 8, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hayward, M.D.; Lu, C. Is There a Hispanic Epidemiologic Paradox in Later Life? A Closer Look at Chronic Morbidity. Research on Aging 2012, 34, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarini, T.E.; Marks, A.K.; Patton, F.; García Coll, C. The Immigrant Paradox in Pregnancy: Explaining the First-Generation Advantage for Latina Adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2015, 25, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lariscy, J.T. Differential Record Linkage by Hispanic Ethnicity and Age in Linked Mortality Studies: Implications for the Epidemiologic Paradox. Journal of Aging and Health 2011, 23, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Garcia, D.; Pan, J.; Jun, H.J.; Osypuk, T.L.; Emmons, K.M. The Effect of Immigrant Generation on Smoking. Social Science and Medicine 2005, 61, 1223–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.R.; Teitler, J.O.; Reichman, N.E. Mexican American Birthweight and Child Overweight: Unraveling a Possible Early Life Course Health Transition. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2011, 52, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, M.C.; Jiménez, T.R. Assessing Immigrant Assimilation: New Empirical and Theoretical Challenges. Annual Review of Sociology 2005, 31, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halstead, J.M.; Deller, S.C. Social Capital and Community Development: An Introduction. In Social capital

at the community level: An interdisciplinary perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, 2015; pp. 1–13 ISBN 978-1-

317-68603-3.

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Chideya, S.; Marchi, K.S.; Metzler, M.; Posner, S. Socioeconomic Status in Health Research: One Size Does Not Fit All. Journal of the American Medical Association 2005, 294, 2879–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavers, V.L. Measurement of Socioeconomic Status in Health Disparities Research. Journal of the National Medical Association 2007, 99, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, G. Social Capital and Its Relevance to Minority and Immigrant Populations. Sociology of Education 2004, 77, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.A. How Do We Assign Ourselves Social Status? A Cross-Cultural Test of the Cognitive Averaging Principle. Social Science Research 2015, 52, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annual Review of Public Health 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaki, S.R.; Seidman, J.C.; Miller, M.; Gottlieb, M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Ahmed, T.; Ahmed, A.S.M.S.S.M.S.; Bessong, P.; John, S.M.; Kang, G.; et al. Measuring Socioeconomic Status in Multicountry Studies: Results from the Eight-Country MAL-ED Study. Population Health Metrics 2014, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Präg, P.; Mills, M.C.; Wittek, R. Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Health in Cross-National Comparison. Social Science and Medicine 2016, 149, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinwiddie, G.Y.; Zambrana, R.E.; Garza, M.A. Exploring Risk Factors in Latino Cardiovascular Disease: The Role of Education, Nativity, and Gender. American journal of public health 2014, 104, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVeist, T.A. Disentangling Race and Socioeconomic Status: A Key to Understanding Health Inequalities. Journal of Urban Health 2005, 82, iii26–iii34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, E.D.; Sanchez, G.R.; Kinlock, B.L. The Enhanced Self-Reported Health Outcome Observed in Hispanics/Latinos Who Are Socially-Assigned as White Is Dependent on Nativity. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2014, 17, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, M.; Cleary, S.; Vyas, A. A Trajectory Model for Understanding and Assessing Health Disparities in Immigrant/Refugee Communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2011, 13, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M. Pre-Migration Trauma and Post-Migration Stressors for Asian and Latino American Immigrants: Transnational Stress Proliferation. Social Indicators Research 2016, 129, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Morshed, A.K.M.M. Dynamics of Immigrant Assimilation: Lessons from Immigrants’ Trust. Journal of Economic Studies 2019, 46, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garip, F. Social Capital and Migration: How Do Similar Resources Lead to Divergent Outcomes? Demography 2008, 45, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesler, C.; Hout, M. Entrepreneurship and Immigrant Wages in US Labor Markets: A Multi-Level Approach. Social Science Research 2010, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; van Holm, E.J. The Geography of Occupational Concentration Among Low-Skilled Immigrants. Economic Development Quarterly 2019, 33, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, T.; Chavez, S. Occupational Linguistic Niches and the Wage Growth of Latino Immigrants. Social Forces 2012, 91, 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.M.; Nee, V. Immigrant Self-Employment: The Family as Social Capital and the Value of Human Capital. American Sociological Review 1996, 61, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annals of Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy – 2021; Matthews, C., Liguori, E., Eds.; Annals in

Entrepreneurship Education; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021; ISBN 978-1-78990-446-8.

- Díaz Fuentes, C.M.; Martinez Pantoja, L.; Tarver, M.; Geschwind, S.A.; Lara, M. Latino Immigrant Day Laborer Perceptions of Occupational Safety and Health Information Preferences. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 2016, 59, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keita, S.; Valette, J. Natives’ Attitudes and Immigrants’ Unemployment Durations. Demography 2019, 56, 1023–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, M.C. From Social Capital to Inequality: Migrant Networks in Different Stages of Labor Incorporation. Sociological Forum 2016, 31, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Coad, A. How Satisfied Are the Self-Employed? A Life Domain View. Journal of Happiness Studies 2016, 17, 1409–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, A. Day Labor Work. Annual Review of Sociology 2003, 29, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.L.; Gorey, K.M.; Haji-Jama, S.; Luginaah, I.N. Care and Survival of Mexican American Women with Node Negative Breast Cancer: Historical Cohort Evidence of Health Insurance and Barrio Advantages. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2015, 17, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD; IRDES Social Capital, Human Capital and Health; OECD Centre for Educational Research and

Innovation, 2010.

- Ryan, L. Migrants’ Social Networks and Weak Ties: Accessing Resources and Constructing Relationships Post-Migration. Sociological Review 2011, 59, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, J.M. The Effects of Driver Licensing Laws on Immigrant Travel. Transport Policy 2021, 105, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, M. Peer Lending and the Subsumption of the Informal. Journal of Cultural Economy 2016, 9, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienda, M.; Raijman, R. Immigrants’ Income Packaging and Invisible Labor Force Activity. Social Science Quarterly 2000, 81, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwellnus, C. Achieving Higher Performance: Enhancing Spending Efficiency in Health and Education in Mexico. Economic Survey of Mexico. 2009, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.; Riddell, W.C. Education, Credentials, and Immigrant Earnings. Canadian Journal of Economics 2008, 41, 186–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, M.L.; Manganello, J.A.; Viswanath, K.; Hesse, B.W.; Arora, N.K. Providing Health Messages to Hispanics/Latinos: Understanding the Importance of Language, Trust in Health Information Sources, and Media Use. Journal of Health Communication 2010, 15, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education.;

Greenwood: Westport, CT, 1987; pp. 241–258 ISBN 0313235295.

- Hilfinger Messias, D.A.K.; McEwen, M.M.; Clark, L.; Mcewen, D.A.K.; Clark, M.M.; Hilfinger Messias, D.A.K.; McEwen, M.M.; Clark, L. The Impact and Implications of Undocumented Immigration on Individual and Collective Health intheUnited States. Nursing Outlook 2015, 63, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, B. Human Capital; OECD Insights; OECD, 2007; ISBN 978-92-64-02908-8.

- Pinxten, W.; Lievens, J. The Importance of Economic, Social and Cultural Capital in Understanding Health Inequalities: Using a Bourdieu-Based Approach in Research on Physical and Mental Health Perceptions. Sociology of health & illness 2014, 36, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Laibson, D.; Sacerdote, B. An Economic Approach to Social Capital. Economic Journal 2002, 112, F437–F458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.L.; Scheffler, R.; Lam, S.; Rosenberg, R.; Rupp, A. Social Capital and Health in Indonesia. World Development 2006, 34, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevalin, D.J.; Rose, D. Social Capital for Health: Investigating the Links between Social Capital and Health Using the British Household Panel Survey; Health Development Agency, 2003; ISBN 1-84279-129-X.

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health. International Journal of Epidemiology 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, M.G.; French, D.; Steptoe, A.; Kee, F.; O ’doherty, M.G.; French, D.; Steptoe, A.; Kee, F.; O’Doherty, M.G.; French, D.; et al. Social Capital, Deprivation and Self-Rated Health: Does Reporting Heterogeneity Play a Role? Results from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Social Science and Medicine 2017, 179, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Kawachi, I. Twenty Years of Social Capital and Health Research: A Glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2017, 71, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, H.P.; Edwards, R.; Goulbourne, H.; Solomos, J. Immigration, Social Cohesion and Social Capital: A Critical Review. Critical Social Policy 2007, 27, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I. The Dark Side of Social Capital: A Systematic Review of the Negative Health Effects of Social Capital. Social Science and Medicine 2017, 194, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gericke, D.; Burmeister, A.; Löwe, J.; Deller, J.; Pundt, L. How Do Refugees Use Their Social Capital for Successful Labor Market Integration? An Exploratory Analysis in Germany. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2018, 105, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Crittenden, V.L. Exploring Customer Orientation as a Marketing Strategy of Mexican-American Entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Research 2020, 113, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, M.A. Social Capital and Immigrant Integration: The Role of Social Capital in Labor Market and Health Outcomes, University of Iowa, 2016.

- Johnson, C.M.; Rostila, M.; Svensson, A.C.; Engström, K. The Role of Social Capital in Explaining Mental Health Inequalities between Immigrants and Swedish-Born: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.M.; Stafford, K.; Haynes, G.; Amarapurkar, S.S. Family Capital of Family Firms: Bridging Human, Social, and Financial Capital. Family Business Review 2009, 22, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, T.; Suzuki, E.; Fujiwara, T.; Takao, S.; Doi, H.; Kawachi, I. Do Bonding and Bridging Social Capital Have Differential Effects on Self-Rated Health? A Community Based Study in Japan. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2012, 66, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancee, B. Job Search Methods and Immigrant Earnings: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Role of Bridging Social Capital. Ethnicities 2016, 16, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton-Salazar, R.D. A Social Capital Framework for the Study of Institutional Agents and Their Role in the Empowerment of Low-Status Students and Youth. Youth and Society 2011, 43, 1066–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijman, R.; Tienda, M. Training Functions of Ethnic Economies: Mexican Entrepreneurs in Chicago. Sociological Perspectives 2000, 43, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.N.H.; Le, T.; McPhee, S.J.; Stewart, S.; Ha, N.T. Health Care Access and Preventive Care among Vietnamese Immigrants: Do Traditional Beliefs and Practices Pose Barriers? Social Science and Medicine 1996, 43, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Bustamante, A.; Chen, J.; Rodriguez, H.P.; Rizzo, J.A.; Ortega, A.N. Use of Preventive Care Services Among Latino Subgroups. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2010, 38, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, S.; Afiouni, F.; Bian, Y.; Ledeneva, A.; Muratbekova-Touron, M.; Fey, C.F. Informal Networks: Dark Sides, Bright Sides, and Unexplored Dimensions. Management and Organization Review 2020, 16, 511–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Bimrose, J.; Nielsen, I.; Zacher, H. Vocational Behavior of Refugees: How Do Refugees Seek Employment, Overcome Work-Related Challenges, and Navigate Their Careers? Journal of Vocational Behavior 2018, 105, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvanov, P.L.; Petkova, N.E. Transformation of Social Capital Into Economic Capital Through Education (By the Example of the European Union and Bulgaria). CBU International Conference Proceedings 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.; Sakdapolrak, P. What Is Social Resilience? Lessons Learned and Ways Forward. Erdkunde 2013, 67, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourat, N.; Wallace, S.P.; Hadler, M.W.; Ponce, N. Assessing Health Care Services Used by California’s Undocumented Immigrant Population in 2010. Health Affairs 2014, 34, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladrich, A. Beyond Welfare Reform: Reframing Undocumented Immigrants’ Entitlement to Health Care in the United States, a Critical Review. Social Science and Medicine 2012, 74, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, S.M.; Kardia, S.L.R. Religion as a Health Promoter During the 2019/2020 COVID Outbreak: View from Detroit. Journal of Religion and Health 2020, 59, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.E.; Boyce, T.; Chesney, M.A.; Cohen, S.; Folkman, S.; Kahn, R.L.; Syme, S.L. Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Challenge of the Gradient. American Psychologist 1994, 49, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampel, F.C.; Krueger, P.M.; Denney, J.T. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology 2010, 36, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, T.D.; Fishbein, D.H.; Krebs, C.P. The Risk of Assimilating? Alcohol Use among Immigrant and U.S.-Born Mexican Youth. Social Science Research 2010, 39, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, C. Evaluating Community-Based Coalitions: An Application of Best Practices to Improve Children’s Health. New Directions for Evaluation 2020, 2020, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Swift, S. The Spectrum of Prevention: Developing a Comprehensive Approach to Injury Prevention. Injury Prevention 1999, 5, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimons, N.M. Partnering with People with Disabilities to Prevent Interpersonal Violence: Organization Practices Grounded in the Social Model of Disability and Spectrum of Prevention. In Religion, Disability, and Interpersonal Violence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau, U. The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018; 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).