1. Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Governance (CG) are one of the emerging concepts, gaining more acceptance with the passage of time. Companies that engage in CSR activities are intrinsically linked to the application of CG (Ningtyas and Sari 2023). CSR refers to a corporation's acts to benefit society that go beyond the law's requirements and the corporation's primary goal, to act in the shareholder's interest (Pearce II and Doh 2005). In contrast, CG is a framework for preserving accountability and aligning the corporation's aims with its stakeholders (Teixeira and Carvalho 2023). CG encompasses a set of processes, principles, and values that impact corporate behaviour and decision-making associated with CSR.

As CSR-focused companies consider the financial as well as social and environmental impacts of their operations activities (Wirba 2023), earlier studies, such as (Vives 2008), have also supported the CSR argument and encouraging organizations to enhance their CSR efforts, recommending them going beyond mandatory standards wherever feasible to embrace voluntary CSR initiatives (and, in doing so, embrace a broader perspective of accountability). Companies are primarily encouraged to make voluntary CSR disclosures. There are several reasons for making voluntary disclosures, including the desire to boost investor confidence, better inform stakeholders, and possibly lower the risk or expense of litigation between stakeholders and the firm. Some benefits of CSR that are more frequently claimed include enhanced social acceptability and the development of a more favourable public image that difficulties related to social responsibility activities are properly managed (Rob et al. 1995; Wilmshurst and Frost 2000).

The board of directors as an important aspect of CG plays a significant role in defining the company's operational actions and strategic decisions, including CSR disclosure decisions. This implies CSR disclosure is an essential part of the board of director's decision-making processes, driven by stakeholder requirements (Fernandez et al. 2014) and restricted by available resources (Katmon et al. 2019). The increased focus on CG and CSR by the media, government, non-governmental organizations, and other key stakeholders has also modified the typical board inclination to include more than simply shareholders' interests. Other stakeholders' interests, in addition to shareholders', are now incorporated in the board's concerns (Fuente et al. 2017).

The board is intended to oversee and advise company management on issues such as risk management and disclosure duties, including CSR disclosure (Hassan et al. 2020). Members of the board of directors are supposed to have the necessary expertise, skills, and credibility for this. This is believed to follow corporations to create a governance structure capable of meeting the interests of key stakeholders (Mallin et al. 2013; Zattoni 2011). This argues that corporations should reconsider the board composition they previously picked to protect shareholders' interests in order to address larger issues. The board has monitoring, managing, advising, and providing accountability responsibilities to shareholders as well as other stakeholders. Corporate disclosures, such as CSR disclosures, are used by boards to discharge responsibilities to stakeholders.

Recent research, such as Riaz et al. (2020)has noticed an increase in CSR disclosures. However, this rise in disclosure has not always mirrored real company performance since the information given may be a management response to perceived stakeholder demands or minor tweaks for disclosure quality, giving the illusion of satisfying accountability responsibilities (Michelon et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2020). This calls into question the legitimacy of CSR disclosures. According to recent research, the makeup of the board is a crucial predictor in meeting stakeholder accountability expectations through voluntary CSR disclosure (Che-Adam et al. 2020; Katmon et al. 2019).

Board diversity is critical for stakeholders and CSR disclosure (Peng et al. 2021). A diverse board is considered to have a good influence on the board's tasks (monitoring, controlling, and advising management), such as achieving stakeholder accountability expectations (Liao et al. 2015). According to Hassan et al. (2020), a more diverse board will be more aware of the expectations of society's many sectors and will endeavour to fulfill these demands. Several board qualities, including gender diversity and independence, have received more attention in research and have been explicitly adopted into practice. For example, in terms of board gender diversity, Norway and other European countries were among the first to establish female board quotas. Some other countries like Australia followed them and declared gender diversity on the board of directors and at senior management levels (Geys and Sørensen 2019). Similarly, in terms of board diversity and independence, the CG code of corporate governance by SECP in 2017 mentioned that listed companies should have female directors on the board and at least one-third of total board members or two independent directors on the board (SECP 2017).

Though scholars have identified substantial relationships between board diversity and CSR disclosure, the majority of their focus has been on the 'quantity' of CSR disclosure rather than the 'quality' (Rao and Carol 2016; Wolniak and Hąbek 2016). Similarly, there is a plethora of CSR research on developed economies as compared to developing countries (Yasser et al. 2017). The implications of CG characteristics on CSR reporting are anticipated to vary between developed and developing nations due to varied institutional, political, social, and cultural settings (Cicchiello et al. 2021); hence need to be investigated. Realizing this, the present study is contributed to filling this research gap by researching the association of selected board characteristics with the CSR disclosure quality in Pakistan as a developing country.

The context of Pakistan provides an interesting scenario for CSR disclosure research, in particular to, the quality of disclosure. For example, prior research (Shahid et al. 2020; Ashraf 2018; Malik 2014; Scamardella 2015; Umair et al. 2015) discovered that companies in Pakistan operate in the context of several CSR issues, such as unfair wages, child labour, human rights violations, and poor living conditions. Similarly, according to the World Bank's study on environmental analysis published in 2022, significant investments in climate resilience are urgently needed to protect Pakistan's economy and alleviate poverty (WB 2022). The motivation to study CSR in the context of Pakistan is also important where prior research, such as Fatima (2017), found the notion of CSR was long deemed too fictitious in Pakistan since firms from all industries were too undeveloped to properly perform their CSR duties included in the definition of CSR. From the gender diversity perspective, Pakistan also provides an interesting case. Pakistan's gender equality rating remains among the lowest in the world (UN 2023). According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2022, Pakistan ranks second-to-last in the gender parity index (WEF 2022), and gender disparity influences the nomination of women to boards (Terjesen et al. 2016).

2. Brief Overview of important CG -CSR arrangements in Pakistan

Due to in particular, its two rounds of CG reforms, Pakistan offers a special instance for research on CG area. These changes were intended to attract foreign direct investment and to put in place worldwide best practices in corporate governance (Gull et al. 2022). The foremost CG code was developed in 2002 and was replaced by the CG code of 2012. SECP made many amendments to the CG Code 2012, and a number of areas, including disclosure and transparency, was more specifically addressed (Gull et al. 2022). Later, for the first time in the history of Pakistan's CG codes and standards, the SECP addressed gender diversity on corporate boards in 2016 and advised each corporate board to include at least one female director. This version of the CG code addressed the composition and structure of the board to improve board independence, managerial supervision, gender diversity, and risk assessment.

Furthermore, the notion of a risk management committee was developed to oversee risk management and corporate governance activities. Companies listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange had to follow the amended 2016 Code. (SECP 2017).

New regulations that superseded the CCG 2012 and aimed to harmonize CG practices were released by SECP in November 2017. In order to improve independent decision-making, new regulations were developed, and the board's position and duties were made clearer and more evident. The board's gender diversity was established and supported, and the system for accountability and openness was strengthened by greater disclosure standards (Asghar et al. 2020; Shahbaz et al. 2020). However, these CG guidelines received some changes later in 2018 by SECP in a number of areas, including CSR disclosures (Asghar et al. 2020).

In case of Pakistan, the Companies Act of 2017, which superseded the previous Companies Ordinance of 1984, was a significant legislative breakthrough and also supported the obligation for a gender quota on the board of listed companies. Furthermore, following this Act, Pakistan made CSR expenditure mandatory for certain types of corporations in 2017. This criterion requires eligible businesses to spend a share of their after-tax income on CSR initiatives. Before this, in 2013, SECP issued voluntary CSR guidelines to encourage greater accountability in business ethics and corporate actions based on the interests of shareholders (Javeed and Lefen 2019).

3. Literature Review and Development of Board Characteristics and CSR Disclosure Quality Hypotheses

Because of the nature of board responsibilities, collaborative work is required, which benefits directors with different experiences who are expected to play a vital part in corporate strategic decision-making processes (Pugliese et al. 2009). Thus, earlier CSR disclosure quality research has taken into account the influence of board diversity features (De Villiers et al. 2011; Katmon et al. 2019; Pucheta-Martínez and Gallego-Álvarez 2019). Gender, board independence, female chairperson, female CEO, and board size have all been studied in previous research (Beji et al. 2020; Fuente et al. 2017; Khan et al. 2019; Pham Hanh Thi and Tran Hien 2019)

3.1. Gender diversity

Greater gender diversity on corporate boards may increase the relevance and faithful representation of CSR disclosures because females have different personality characteristics and values in CSR subjects than males (Aldamen et al. 2018; Rao and Tilt 2016; Rao et al. 2012b). Female directors may also be more sensitive to social and environmental activities (Hafsi and Turgut 2013; Isidro and Sobral 2015; Liao et al. 2018), and their particular leadership style may contribute more to the quality of CSR disclosure (Liu 2018). An increase in the number of female board directors, for example, raises the likelihood of varied board room talks concerning stakeholder expectations (Nekhili et al. 2017). Discussions on stakeholder expectations that are diverse and educated are more likely to contribute to the relevance aspect of CSR disclosure quality. The relevant component of CSR disclosure quality includes CSR strategy, CSR risks, stakeholder involvement, and overall CSR performance disclosures. In comparison to male directors, growth in female board directors has boosted the relevant component of CSR disclosure quality; female directors have been observed to have a broader stakeholder orientation (Shaukat et al. 2016).

Gender diversity on corporate boards is expected to result in stronger CSR benefits, such as higher CSR disclosure quality. This study expects to find a positive relationship between a board's gender diversity and CSR disclosure quality, which is consistent with previous research findings (Al-Shaer and Zaman 2016; Barako and Brown 2008; Bear et al. 2010; Ismail et al. 2019; Liao et al. 2015; Rupley et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2013). The following hypothesis is offered about gender diversity and the quality of CSR disclosure:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): A positive association exists between the board gender diversity and the CSR disclosure quality.

3.2. Board independence

Board independence has been considered to be critical for boards in carrying out their responsibilities (Carter et al. 2003). The board of directors, for example, has a monitoring responsibility that involves questioning the CEO and other senior management on behalf of shareholders. Independent non-executive directors who are not affiliated with management are supposed to support the quality of CSR discourse and provide more 'relevance' in CSR disclosure. Independent board members are required to embrace stakeholders' broader interests and work to match these interests with the company. Non-executive and independent directors may be anticipated to encourage companies to disclose voluntary information to stakeholders since they are less linked with corporate management (Eng and Mak 2003; Katmon et al. 2019).

Prior disclosure studies have indicated support for a larger number of independent board directors, lowering agency costs and putting pressure on management to reveal more information (M. Shamil et al. 2014). Since they are often more interested in CSR than in business economic and financial performance (Ibrahim and Angelidis 1995), previous research has demonstrated a positive connection between board independence and the quantity and quality of CSR and environmental disclosures (Barako and Brown 2008; Liao et al. 2015; Post et al. 2011; Rupley et al. 2012). In regard to board independence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): A positive association exists between the board independence and the CSR disclosure quality.

3.3. Female Leadership

Previous studies (Brammer et al. 2007; Harrison and Coombs 2012) claimed that top female executives were more successful than male leaders in integrating different stakeholder and shareholder interests. According to prior research (Ellwood and Garcia-Lacalle 2015; Malik et al. 2020), females have a substantial and positive effect on corporate decision-making, company success, and social performance.

Although both female CEOs and female Chairpersons are anticipated to have a good influence, a study by Kang et al. (2010) found that a female chairperson is more acceptable than a female CEO. They discovered that when a female is put in an independent roles, such as chairperson rather than a managerial position, the market reacts more positively. The nomination of a female chairperson and CEO has been linked to increased interest in conflict resolution and has been linked to increased CSR reporting (Furlotti et al. 2019). According to Jiang and Akbar (2018), firms with female chairs or CEOs prioritize CSR issues and concerns. In regard to female leadership roles, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): A positive association exists between the female chairperson and the CSR disclosure quality.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): A positive association exists between the female CEO and the CSR disclosure quality.

3.4. Board size

The total number of members on a corporate board is referred to as board size. The size of a board can have an impact on CG and CSR practices. Increased board size can have an influence on the board's efficacy and efficiency since it can impede decision-making and raise the likelihood of a lack of unanimity (Rao et al. 2012a). On a bigger board, directors might engage in free-riding and dodge duties, allowing control to be concentrated in the hands of a few board members. This may have an adverse effect on CSR efforts and disclosure (Ntim and Soobaroyen 2013).

The overall effects of board size on CSR disclosure are mixed. Some research (Rao et al. 2012b) discovered a substantial and favorable association between board size and CSR disclosure, while others (Said et al. 2009a; Yasser et al. 2017) discovered a significant but negative relationship. Similarly, several disclosure studies have found that board size has no effect (Katmon et al. 2019; Yekini et al. 2015). Given the conflicting findings of previous research, this study does not anticipate a direction for the relationship between board size and CSR disclosure quality. In regard to board size, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): An association exists between the female CEO and the CSR disclosure quality.

4. Empirical Research Design

4.1. Sample size and study period

The population for this study was drawn from all 412 PSX-listed firms as of June 2019. A selection of the top 100 corporations in Pakistan's capital markets based on market capitalization was selected from among them. This study followed the previous CSR studies, such as Akhtaruddin and Rouf (2012); Ghazali (2007); Muttakin et al. (2015); Rao et al. (2012b), also looked at listed companies since they are more likely to engage in CSR disclosure as a consequence of stakeholder expectations. Listed companies are more likely to follow CG guidelines that urge enterprises to publish CSR disclosures and propose that boards be diverse and independent. Due to the inability of several firms to provide essential time period data, the final sample of this study was reduced to 94 PSX companies (see

Table 1).

Because of several specific considerations of the context of this study, such as the time required for listed companies in Pakistan to comply with CSR guidelines of 2013, CG developments since 2016, and pre-covid reliable data concentration of all samples, the study period is comprised of 2017 and 2018. However, for just one characteristic of the CSR disclosure index, ‘comparability’, (i.e., see

Table 2), data from 2016 is also included. Intensive laborious efforts are required from the standpoint of the self-developed database for all the CSR and CG variables in this study. According to Beattie and Thomson (2007), analyzing the disclosure contents takes substantial labour activity, which limits the sample size.

4.1. Variables and measurements

This study examines the association between various board characteristics and CSR disclosure quality. Therefore, CSR disclosure quality is considered as a dependent variable, and board characteristics are considered independent variables.

4.1.1. Dependent variable- CSR disclosure quality

To calculate the CSR disclosure quality, we followed an earlier research (Faisal 2021) and used a ‘self-developed CSR disclosure index’ computed from various secondary sources data. This index is based on the qualitative information characteristics of International Conceptual Frameworks (ICF), which is a highly recognized and acceptable standard across the world. In the selected ‘CSR disclosure index,’ the five dimensions of CSR disclosure information (i.e., Relevance, Faithful Representation, Understandability, Comparability, and Timeliness) are covered through fifteen sub-categories, and each of these dimensions requires a different calculation mechanism to determine the CSR disclosure quality, that is referred as ‘Total CSR disclosure quality’ (TCSRDQI) in this study and is presented in detail in

Table 2.

We used the content analysis technique to calculate ‘CSR disclosure quality’. We believe that the importance and desire of company management to guarantee disclosure quality will be reflected in the published CSR information (Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Krippendorff 2004). Earlier CSR disclosure studies frequently used content analysis (Ali et al. 2017; Lock and Seele 2016; Kennedy Nyahunzvi 2013). In terms of disclosure procedures, content analysis is a very unobtrusive, simple research approach that collects data from real reports to stakeholders (Allen 2017; McGraw and Katsouras 2010).

For content analysis at the first stage, three years of CSR disclosures (2016-2018) for PSX 100 companies are inspected and downloaded in PDF format. Annual reports of sample firms are used for this since relatively few independent CSR, sustainability, or other related reports were available throughout the research period. Within NVivo 12, a data collecting and coding procedure was created, and decision criteria were implemented to improve reliability. These decision criteria guided the coder in determining the precise score to be assigned to each disclosure item if the circumstances were met. The Flesch Reading Ease Index band is also calculated to find the score of the understandability criteria. Each report is evaluated using the online readability evaluation tool. Each coding choice criterion was reviewed before and after the pilot study, and any differences were corrected.

A pilot study was conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the coding and make any necessary improvements. Based on their market capitalization, twenty firms were chosen at random from each of the six major industries. Both authors coded all of the reports and afterward examined the coding procedure and CSR disclosure quality scores. Any variations between them were assessed, and coding standards were changed as needed to enhance reliability. Only minor variations were discovered, and changes were made to improve clarity and guarantee that no items were missing or misconstrued. This study uses Krippendorff's Alpha, the error percentage, to assess the inter-coder reliability of the two studies. The Krippendorff's Alpha coefficient for each index disclosure feature varies from 0.90 to 0.96. According to Rao and Carol (2016), the fact that all values of Krippendorff's Alpha stayed above 0.90 indicates a high level of coding agreement. To summarize, several precautions were taken to ensure the validity of the findings in this study. For example, experienced researchers assessed the disclosure index and its criteria; afterward, a pilot study was conducted to confirm the reliability of the data-gathering procedure needed by the index.

4.1.2. Independent and control variable

The present study, from the CG perspective, has selected five independent variables utilizing a combination of widely studied board characteristics: gender diversity, board independence, female chairperson, female CEO, and board size. It is also required to gather data for all firm-level control variables in this investigation; therefore, corporate annual reports and individual firm websites were also used. In certain circumstances, internet databases like Bloomberg, Data Analysis Premium by Morningstar, and Reuters are used since needed information is missing or unavailable in annual reports. All hand-collected data needed considerable effort, including assessing, reading, and recording. For example, in this study's board diversity variable, the gender of directors was determined from their names and reading the director biographies. Once the gender was determined, the figures were validated with director photographs. In situations where director photographs were unavailable or any confusion existed, revealed pronouns (that is, his/her) were used to establish a conclusion. The overall number of female and male directors was compared to board size statistics. Data for the remaining needed independent and control variables was acquired in a similar manner.

Table 3 provides the details of symbols and measurements adopted for the operationalizations of independent and control variables of the present study.

5. Empirical Results and Discussions

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of all the dependent, independent and control variables of the study were calculated, and results are presented in

Table 4.

The dependent variable ‘CSR Disclosure Quality’ for the PSX sample was 1.76 out of 5 with a standard deviation of .44, and there was less variance between PSX companies, although quality disclosure was, on average at a lower level. This indicates a very low CSR disclosure quality information in our sample.

Regarding board characteristics, on average, 10% of directors on the boards of the PSX sample were female, and 32% of independent and non-executive directors. On average, 4% of board chairpersons and 2% of CEOs are female, whereas on average, PSX 100 companies have eight members on their boards.

The control variables adopted in this study were profit, leverage, liquidity, and company size. Overall, PSX companies are not very profitable, with a result ratio of only 2.58% return of PSX companies. It is also noticed that 24% of total assets were financed by the debt finance method in the PSX 100 companies. The companies in the sample have more current assets than their current liabilities, and the liquidity ratio was 1.4; most of these are sizable companies in terms of their total assets.

5.2. Univariate Analysis

Univariate analysis was undertaken to assess the impact of each board characteristic (independent variables) on CSR disclosure quality. The objective was to identify which characteristics, if any, of the board (independent variables) and company (control variables) may impact CSR disclosure quality. To achieve this, a distinction was made between high-CSR-quality and low-CSR-quality disclosure companies. The distinction between high and low CSR quality disclosure was made by referencing the mean CSR quality disclosure. Companies falling above the mean were included as high CSR quality disclosing companies and those below as low CSR quality disclosures. The differences between these two groups were identified through two sample t-test statistics (used for the continuous variables) and Chi-square tests (used for the dichotomous variables).

The results of the univariate analysis of continuous and dichotomous variables are presented in Tables 5.1 and 5.2, respectively.

Table 5.1.

Univariate analysis results of continuous variables.

Table 5.1.

Univariate analysis results of continuous variables.

| |

Low CSR

Disclosure Quality

(n = 51) |

High CSR disclosure Quality

(n = 43) |

Two Sample

t-test

Statistics |

Variables |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean

Difference |

Gender

Diversity |

0.1 |

0.13 |

0.1 |

0.12 |

0.001 |

Board

Independence |

0.33 |

0.12 |

0.31 |

0.11 |

0.026 |

| Board Size |

8.28 |

2.07 |

8.77 |

1.89 |

–0.483 |

| Profit |

0.29 |

11.59 |

5.29 |

5.09 |

-4.990*** |

| Leverage |

0.28 |

0.34 |

0.21 |

0.2 |

0.067 |

| Liquidity |

1.58 |

1.72 |

1.15 |

1.13 |

0.4223* |

| Company Size |

7.47 |

0.72 |

7.96 |

1.05 |

–0.489*** |

Table 5.2.

Univariate analysis results of Dichotomous variables.

Table 5.2.

Univariate analysis results of Dichotomous variables.

| |

Low CSR

Disclosure Quality

(n = 51) |

High CSR disclosure Quality (n = 43) |

Pearson Chi- Square |

Variables |

Without |

With |

Without |

With |

Mean

Difference |

| Female Chairperson |

47 |

4 |

43 |

0 |

2.859 |

| Female CEO |

49 |

2 |

43 |

0 |

1.723 |

It is necessary to analyse the company-level variable (control variables) as the board characteristics (independent variables) under investigation do not impact disclosure quality in isolation. The univariate analysis identifies the characteristics of all the variables in the study. The results show 51 of 94 PSX sample companies have a low CSR disclosure quality (a mean score less than 1.76, see

Table 4) compared to 43 high CSR disclosure quality companies. Interestingly, in reference to the independent variables in the PSX sample, there are no significant differences between high CSR disclosure quality and low CSR disclosure quality companies. However, the results shown for the control variables indicate that several variables may potentially impact the association between board characteristics and CSR disclosure quality. This means some company-level (control) variables were found to potentially impact the association between board characteristics and CSR disclosure quality. For instance, company size and profitability were highly significant (at the 1% level), while liquidity was less significant at the 10% level only.

In sum, the results of the univariate analysis indicate differences in the impact of variables between firms with high/low CSR disclosure quality. To develop a more reliable conclusion, the impact of board characteristics on CSR disclosure quality is examined in a multivariate setting and discussed next.

5.3. Correlation Analysis

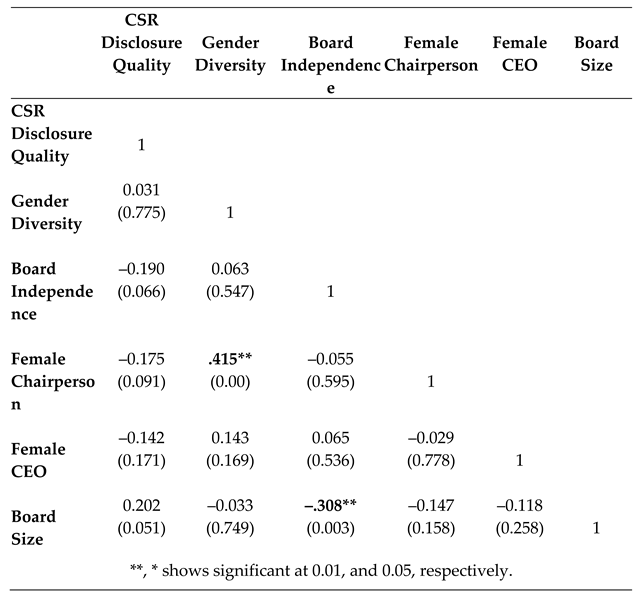

We have conducted the correlation analysis, and the results are presented in

Table 6. In our study, the correlations between CSR disclosure quality and all independent variables are insignificant. However, the correlation between independent variables such as gender diversity and female chairperson is 0.415 and significant at the 1% level. Similarly, the correlation between board Size and board independence is also above –0.30 and significant at the 1% level. The high correlation value meets the threshold limit of less than 0.8, as recommended by Gujarati (2009). Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance scores were calculated (discussed in next under the regression analysis section), and these scores indicate the absence of multicollinearity between the independent variables.

5.4. Multiple Regression Analysis

For the multivariate analysis, we have used the conventional Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method in order to produce the best feasible estimations, which corresponds to previous board characteristics and CSR disclosure research (Ahmad et al. 2017; Rezaee et al. 2021). A variety of OLS assumptions (normality, multicollinearity, autocorrelation, and homoscedasticity) were used to determine whether they are valid for our study.

Using Pearson's correlation and computing the VIF and Tolerance ratings of all independent variables, it was found that there are unlikely to be any concerns influencing the results.

Table 7 demonstrates that, as Thompson et al. (2017) indicated, all VIF values are less than 10, and all Tolerance scores are less than 0.

Some OLS linear regression assumptions, such as no multicollinearity, are also fully met. Other assumptions, on the other hand, are not met when the data is not normally distributed. As a result, this work builds on prior research (Hoang et al. 2018; Adib et al. 2019) that addressed comparable difficulties by doing regression analysis with robust standard errors using STATA. This approach will produce reliable findings that will overcome data normality concerns.

The results of the multiple regression analysis are calculated using the following regression equation through STATA and presented in

Table 8.

TCSRDQI = β0 + β1Gendrdivit + β2Independit + β3 Femchairit + β4 FemCEOit + β5 Bsizeit + β6 Profit + β7FrmLevit + β8FrmLiqit + β09 Comsizeit + Σ10k=1 β10INDit + ɛ

Where i represents the company, and t = time as the sample year (that is, 2017–18), the intercept is β0, β1 – β10 are coefficients, and ɛ is the error term. TCSRDQI = CSR disclosure quality is the dependent variable

In

Table 8, regression findings of the adjusted R

2 value of 0.47 suggest our model can explain the influence of the specified variables at acceptable levels. According to Chin (1998), values of R

2 up to 67% may describe large variation, but values of 33% and 19% can only explain moderate and weak variation levels, respectively. Prior board diversity and CSR disclosure studies in Pakistan (Ismail et al. 2019; Khan et al. 2019) have produced R square values in the 0.15-0.43 range. As a result, in the context of a developing nation like Pakistan, there appear to be more characteristics that future studies should discover and investigate.

We can see that gender diversity, while positively related to CSR disclosure quality, did not reveal a meaningful association, but a female chairperson was considerably significant at the 1% level. Profit and firm size are positive and significant control factors in terms of CSR disclosure quality for PSX 100 companies. For PSX corporations, the association between leverage and liquidity and CSR disclosure quality is insignificant.

This means that the gender diversity hypothesis (H1) did not get any support from the regression results showing an insignificant association with CSR disclosure quality; therefore, it is rejected. Female directors were predicted to be more sensitive to societal concerns and to make the board more aware of social expectations (Galbreath 2016), hence enhancing the quality of CSR disclosure. However, considering the dearth of female diversity on PSX firm boards (i.e., mean of 0.09), these findings were predictable. The existing degree of board gender diversity in PSX 100 companies is not a reliable predicator of the quality of CSR disclosure. The findings of this study are congruent with those of Naseem et al. (2017), who discovered an insignificant impact of board diversity in Pakistan companies.

Board independence, like gender diversity, had an insignificant relationship with CSR disclosure quality; hence, H2 is not supported. These findings were unexpected because the increased number of independent directors was expected to strengthen senior management oversight. The modest number of independent non-executive directors on PSX boards (mean of 0.32) may explain the insignificant association between board independence and CSR disclosure quality. As a result, it is expected that PSX boards were more inclined to back financial considerations. According to Handajani et al. (2014), independent directors are a prerequisite of capital markets and the stock exchange, resulting in boards that are focused on the interests of shareholders rather than a broader spectrum of stakeholders. Previous studies (Amran et al. 2014; Chau and Gray 2010; Habbash 2016; Haniffa and Cooke 2005; Garcia-Torea et al. 2016; Sundarasen et al. 2016), discovered an insignificant and negative relationship between board independence and CSR disclosures.

The regression findings revealed a significant negative relationship between female leadership, as chairman or CEO, and the quality of CSR disclosure. Nonetheless, the regression findings show a substantial and negative relationship between female leaders and CSR disclosure quality, providing partial support for two hypotheses (i.e., H3 and H4). This study anticipated a positive relationship between a female chairperson and CEO and CSR disclosure quality because female leaders are more likely to prefer CSR disclosure and be more active in accepting responsibility and developing relevant disclosure to stakeholders (Brammer et al. 2007; Harrison and Coombs 2012; Jiang and Akbar 2018). When a female becomes chairperson, the 'female' responsibilities change: female directors and female chairpersons adopt a masculine stereotype toward voluntary disclosures (Amorelli and García-Sánchez 2020). Several previous investigations have discovered this role shift (Lee and James 2007; Powell and Butterfield 2002). However, given the lack of female representation on boards and in CEO/chairperson leadership roles in companies, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions. PSX company boards had just 4% female chairpersons and 2% female CEOs. The findings of a negative correlation between female chairpersons and CEOs on CSR disclosure quality contradict the findings of Furlotti et al. (2019), who discovered a positive association.

The regression findings for board size also revealed a statistically insignificant relationship, thus not supporting H5. According to Rao et al. (2012a) an increase in board members is more likely to affect the efficacy of board decision-making. For example, with big boards, it may be difficult to establish consensus among varied viewpoints, which has a substantial influence on a board's monitoring and advising abilities (Lipton and Lorsch 1992). The findings are congruent with those of Amran et al. (2014), Katmon et al. (2019), and Yekini et al. (2015), who found that board size had no effect on CSR disclosure. Esa and Anum Mohd Ghazali (2012), Rao et al. (2012a), Said et al. (2009b), and Yasser et al. (2017), on the other hand, found a strong relationship between board size and CSR disclosure quality. As with the previous theories, the results appear to be mixed.

Among all financial measures used by PSX companies as a control variable, only profitability was positively and significantly related to CSR disclosure at the 5% level of significance. Several earlier studies (for example, Cheung et al. (2012); Jizi et al. (2014)) revealed that profit has a positive and significant effect on the quality of CSR disclosure.

In the other financial indicators, financial leverage and liquidity have no statistically significant relationship with CSR disclosure quality. In the Pakistani context, Javaid et al. (2016) and Ismail et al. (2019), discovered that firm leverage had an insignificant relationship with the quality of CSR disclosure. Management of PSX 100 companies is likely to have stronger contacts with their creditors and shareholders and to be more concerned with mandated disclosures than with CSR disclosure quality (Fatima 2017).

The findings of the liquidity ratio for PSX 100 companies demonstrate little correlation with the quality of CSR disclosure. A number of studies (Omair Alotaibi and Hussainey 2016; Barako et al. 2006; Elzahar and Hussainey 2012) indicated that liquidity had no effect on CSR disclosure quality. These findings contradict those of Al-Moataz and Hussainey (2013), Mathuva (2015), and Nandi and Ghosh (2013), all of which indicated a substantial correlation.

At the 5% level, the size of PSX companies demonstrated a significant positive connection with CSR disclosure quality. This suggests that company size is connected to the quality of CSR disclosure in Pakistan. Companies with high CSR disclosure quality and poor CSR disclosure quality were related to a significant difference in PSX companies in the univariate Analysis. Larger PSX firms are more likely to produce higher quality CSR disclosure owing to increased visibility than smaller PSX companies. Many previous studies (Adel et al. 2019; Brammer and Pavelin 2008; Dias et al. 2017; Katmon et al. 2019; Liao et al. 2015; Omair Alotaibi and Hussainey 2016; Sulaiman et al. 2014) discovered a substantial positive relationship between firm size and CSR disclosure quality.

The industries in which PSX companies operate were expected to have an influence on the quality of CSR disclosure. Prior research has found mixed evidence for industry as a control variable (Haniffa and Cooke 2005; Ho and Shun Wong 2001). The Health Care industry in our PSX sample was chosen as the baseline for comparison with other industries, and this also belongs to the highest CSR disclosure quality of any industrial category. Its disclosure quality score was comparable to the Energy and Materials industry groupings. Consumer Staples, Energy, Industrials, and Materials regression findings revealed minimal variations in CSR disclosure quality. Consumer Staples companies are well-known to the public because they engage in activities with a strong social effect. As a result, they are more likely to have greater CSR disclosure quality, as Gamerschlag et al. (2011) discovered. Similarly, it has been stated that the Energy, Industrials, and Materials industries will have a larger motivation for quality CSR disclosure because they represent a particularly ecologically sensitive business. However, for other industrial groupings, the correlation with the quality of CSR disclosure reveals some substantial differences. Telecommunication Services and Financials, for example, have significantly worse CSR disclosure quality than Health Care (at the 1% level). The Telecommunications, IT, and Financials industrial groupings had the lowest levels of disclosure as compared to the Health Care industry. Similarly, the disclosure quality of the Real Estate and Utilities industry groups was significant at the 5% level, while Consumer Discretionary was significant at the 10% level, according to the regression findings. As a result, industry group appears to have an influence on the quality of CSR disclosure.

6. Conclusion

To study the association of five board characteristics, namely board gender diversity, independence, female leaderships, board size as, and CSR disclosure quality in the context of Pakistan, we have provided some noteworthy conclusions. After using the univariate and multivariate analysis techniques, we found neither gender diversity nor board independence has any significant role in promoting the CSR disclosure quality of listed companies in Pakistan. Companies with ‘high CSR disclosure quality’ were not different in gender diversity from companies with ‘low CSR disclosure quality’. A real dearth of female directors on corporate boards (only 10 percent) and independent directors (only 32 percent) seems to have consequences for promoting the CSR disclosure quality. Similarly, concerning the role of a female chairperson and CEO, there was no indication that this might increase the CSR disclosure quality. More surprisingly, companies with ‘high CSR disclosure quality’ did not have a female CEO and chairperson. A female chairperson and CEO in Pakistan were likely to change concerns in terms of broader stakeholder groups. Lastly, board “size” was consistent with previous board characteristics, and there is no sign of increasing CSR disclosure quality. The possible problems associated with decision-making in the larger board’s context may reduce attention to CSR disclosure quality; this is why we found greater CSR disclosure quality is associated with fewer members on the board.

Overall, this means, in Pakistan’s context, corporate boards have been shown to underestimate wider stakeholder demands and concerns for providing more accountability through CSR disclosure quality. This is not much of a surprise, as earlier research (Ali et al. 2017; Momin and Parker 2013) found companies in low-income countries have less public pressure for CSR disclosure than their counterparts in advanced economies. Companies in underdeveloped nations are typically under more pressure to adhere to commercial and economic objectives than social and environmental ones.

7. Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Our study provides important implications for policymakers and regulators. For instance, the listed companies and regulators need to emphasize increasing the present level of diversity and independent non-executive directors on corporate boards. Similarly, regulators such as SECP need to emphasize policies linked to promoting the quality of CSR disclosure instead of the quantity of CSR discourse.

The present study is not without limitations; because of the limited resource availability, especially considering the need for self-developed approaches for CG and CSR data collection, we must restrict our study period, which is only two years. This offers future research opportunities to develop studies on longitudinal aspects. Also, a comparative analysis of two times, such as pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19, can offer more valuable outcomes in the context of the studied relationship. Moreover, the impact of other board characteristics such as age, educational level, ethnic background, and multiple directorships on CSR disclosures should be contemplated, acknowledging that the present study just considered the most common board characteristics. Furthermore, future research can be developed on the lines of the application of system theories perspectives, including legitimacy theory, Stakeholders theory, and institutional theory, to offer a different insight into the association to board characteristics and CSR disclosure quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H.; data curation, F.H. and K.H; formal analysis, F.H.; methodology, F.H., and K.H.; validation, F.H. ; writing—original draft preparation, F.H. and K.H.; writing—review and editing, F.H. and K.H.; supervision, K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The reports analyzed are available on the companies’ websites. The data can be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adel, C., M. Hussain Mostaq, K. A. Mohamed Ehab, and A. K. Basuony Mohamed. 2019. Is corporate governance relevant to the quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure in large European companies? International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 27 (2):301-332.

- Adib, M., Z. Xianzhi, and V. Eiris. 2019. Board characteristics and Corporate Social Performance nexus-a multi-theoretical analysis-evidence from South Africa. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 21 (1):24-38.

- Ahmad, N. B. J., A. Rashid, and J. Gow. 2017. Board independence and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting in Malaysia.

- Akhtaruddin, M., and M. A. Rouf. 2012. Corporate Governance, Cultural Factors and Voluntary Disclosure: Evidence from Selected Companies in Bangladesh. Corporate Board: Role, Duties & Composition 8 (1):46-58.

- Al-Moataz, E., and K. Hussainey. 2013. Determinants of corporate governance disclosure in Saudi corporations. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Economics & Administration 27 (2).

- Al-Shaer, H., and M. Zaman. 2016. Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 12 (3):210-222.

- Aldamen, H., J. Hollindale, and J. L. Ziegelmayer. 2018. Female audit committee members and their influence on audit fees. Accounting & Finance 58 (1):57-89. [CrossRef]

- Ali, W., J. G. Frynas, and Z. Mahmood. 2017. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24 (4):273-294. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. 2017. The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods: Sage Publications.

- Amorelli, M.-F., and I.-M. García-Sánchez. 2020. Critical mass of female directors, human capital, and stakeholder engagement by corporate social reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27 (1):204-221.

- Amran, A., P. Lee, and S. Devi. 2014. The Influence of Governance Structure and Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility Toward Sustainability Reporting Quality. Business strategy and the environment 23 (4):217-235. [CrossRef]

- Asghar, T. N., T. Mortimer, and M. Bilal. 2020. Corporate Governance Codes in Pakistan: A. Review. Journal of Law & Social Studies (JLSS) 2 (2):51-56.

- Ashraf, S. 2018. CSR in Pakistan: The case of the Khaadi controversy. Corporate responsibility and digital communities: An international perspective towards sustainability:247-269.

- Barako, D. G., and A. M. Brown. 2008. Corporate social reporting and board representation: evidence from the Kenyan banking sector. Journal of Management & Governance 12 (4):309.

- Barako, D. G., P. Hancock, and I. Izan. 2006. Relationship between corporate governance attributes and voluntary disclosures in annual reports: the Kenyan experience. FRRaG (Financial Reporting, Regulation and Governance) 5 (1):1-26.

- Bear, S., N. Rahman, and C. Post. 2010. The Impact of Board Diversity and Gender Composition on Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 97 (2):207-221. [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V., and S. Thomson. 2007. Lifting the lid on the use of content analysis to investigate intellectual capital disclosures. Accounting Forum 31 (2):129-163. [CrossRef]

- Beji, R., O. Yousfi, N. Loukil, and A. Omri. 2020. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S., A. Millington, and S. Pavelin. 2007. Gender and Ethnic Diversity Among UK Corporate Boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15 (2):393-403.

- Brammer, S., and S. Pavelin. 2008. Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure. Business strategy and the environment 17 (2):120-136. [CrossRef]

- Branco, M. C., and L. L. Rodrigues. 2006. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics 69 (2):111-132. [CrossRef]

- Carter, D., B. Simkins, and G. Simpson. 2003. Corporate Governance, Board Diversity, and Firm Value. The Financial Review 38.

- Chau, G., and S. Gray, J. 2010. Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 19 (2):93-109. [CrossRef]

- Che-Adam, N., N. A. Lode, and H. Abd-Mutalib. 2020. The influence of board of directors ‘characteristics on the environmental disclosure among Malaysian companies. Malaysian Management Journal 23:1-25. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.-L., K. Jiang, and W. Tan. 2012. ‘Doing-good’ and ‘doing-well’ in Chinese publicly listed firms. China Economic Review 23 (4):776-785.

- Chin, W. W. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research 295 (2):295-336.

- Cicchiello, A. F., A. M. Fellegara, A. Kazemikhasragh, and S. Monferrà. 2021. Gender diversity on corporate boards: How Asian and African women contribute on sustainability reporting activity. Gender in Management: An International Journal 36 (7):801-820. [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C., V. Naiker, and C. J. Van Staden. 2011. The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. Journal of Management 37 (6):1636-1663. [CrossRef]

- Dias, A., L. Lima Rodrigues, and R. Craig. 2017. Corporate governance effects on social responsibility disclosures. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 11 (2):3-22.

- Ellwood, S., and J. Garcia-Lacalle. 2015. The Influence of Presence and Position of Women on the Boards of Directors: The Case of NHS Foundation Trusts. Journal of Business Ethics 130 (1):69-84. [CrossRef]

- Elzahar, H., and K. Hussainey. 2012. Determinants of narrative risk disclosures in UK interim reports. The Journal of Risk Finance 13 (2):133-147. [CrossRef]

- Eng, L. L., and Y. T. Mak. 2003. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of accounting and public policy 22 (4):325-345.

- Esa, E., and N. Anum Mohd Ghazali. 2012. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in Malaysian government-linked companies. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 12 (3):292-305. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, F. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Exploring Disclosure Quality in Australia and Pakistan: the context of a developed and developing country, School of Business and Economics (TSBE), University of Tasmania.

- Fatima, M. 2017. A comparative study of CSR in Pakistan! Asian Journal of Business Ethics 6 (1):81-129.

- Fernandez, F., S. Romero, and B. Ruiz. 2014. Women on boards: do they affect sustainability reporting? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 21 (6):351-364.

- Fuente, G. Sánchez, and Lozano. 2017. The role of the board of directors in the adoption of GRI guidelines for the disclosure of CSR information. Journal of Cleaner Production 141:737-750.

- Furlotti, K., T. Mazza, V. Tibiletti, and S. Triani. 2019. Women in top positions on boards of directors: Gender policies disclosed in Italian sustainability reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (1):57-70. [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. 2016. The Impact of Board Structure on Corporate Social Responsibility: A Temporal View. Business strategy and the environment. [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R., K. Möller, and F. Verbeeten. 2011. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: empirical evidence from Germany. Review of Managerial Science 5 (2):233-262. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torea, N., B. Fernandez-Feijoo, and M. de la Cuesta-González. 2016. The influence of ownership structure on the transparency of CSR reporting: empirical evidence from Spain. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting / Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Geys, B., and R. J. Sørensen. 2019. The impact of women above the political glass ceiling: Evidence from a Norwegian executive gender quota reform. Electoral Studies 60:102050. [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, M. 2007. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Some Malaysian evidence. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 7 (3):251-266.

- Gujarati, D. N. 2009. Basic econometrics: Tata McGraw-Hill Education.

- Gull, A. A., A. Abid, K. Hussainey, T. Ahsan, and A. Haque. 2022. Corporate governance reforms and risk disclosure quality: evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 13 (2):331-354. [CrossRef]

- Habbash, M. 2016. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Social Responsibility Journal 12 (4):740-754. [CrossRef]

- Hafsi, T., and G. Turgut. 2013. Boardroom Diversity and its Effect on Social Performance: Conceptualization and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 112 (3):463-479. [CrossRef]

- Handajani, L., B. Subroto, T. Sutrisno, and E. Saraswati. 2014. Does board diversity matter on corporate social disclosure? An Indonesian evidence. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 5 (9):8-16.

- Haniffa, R. M., and T. E. Cooke. 2005. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of accounting and public policy 24 (5):391-430. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. S., and J. E. Coombs. 2012. The Moderating Effects from Corporate Governance Characteristics on the Relationship Between Available Slack and Community-Based Firm Performance. Journal of Business Ethics 107 (4):409-422. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L. S., N. M. Saleh, and I. Ibrahim. 2020. Board diversity, company’s financial performance and corporate social responsibility information disclosure in Malaysia. International Business Education Journal 13 (1):23-49.

- Ho, S. S. M., and K. Shun Wong. 2001. A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure7 7The helps given by the two anonymous reviewers and the Editors are gratefully acknowledged. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 10 (2):139-156.

- Hoang, T. C., I. Abeysekera, and S. Ma. 2018. Board diversity and corporate social disclosure: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Business Ethics 151:833-852. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N. A., and J. P. Angelidis. 1995. The corporate social responsiveness orientation of board members: Are there differences between inside and outside directors? Journal of Business Ethics 14 (5):405-410.

- Isidro, H., and M. Sobral. 2015. The Effects of Women on Corporate Boards on Firm Value, Financial Performance, and Ethical and Social Compliance. Journal of Business Ethics 132 (1):1-19. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K., K. Imran, and B. b. Saeed. 2019. Does board diversity affect quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure? Evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 0 (0).

- Javaid, E., A. Ali, and I. khan. 2016. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from Pakistan. The International Journal of Business in Society 16 (5):785-797. [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S. A., and L. Lefen. 2019. An analysis of corporate social responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: A case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 11 (1):248. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., and A. Akbar. 2018. Does increased representation of female executives improve corporate environmental investment? Evidence from China. Sustainability 10 (12):4750. [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M., A. Salama, R. Dixon, and R. Stratling. 2014. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector. Journal of Business Ethics 125 (4):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Kang, E., D. K. Ding, and C. Charoenwong. 2010. Investor reaction to women directors. Journal of Business Research 63 (8):888-894.

- Katmon, N., Z. Z. Mohamad, N. M. Norwani, and O. A. Farooque. 2019. Comprehensive Board Diversity and Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from an Emerging Market. Journal of Business Ethics 157 (2):447-481. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy Nyahunzvi, D. 2013. CSR reporting among Zimbabwe's hotel groups: a content analysis. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 25 (4):595-613.

- Khan, I., I. Khan, and I. Senturk. 2019. Board diversity and quality of CSR disclosure: evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 19 (6):1187-1203.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content analysis : an introduction to its methodology: Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage, c2004. 2nd ed.

- Lee, P. M., and E. H. James. 2007. She'-e-os: gender effects and investor reactions to the announcements of top executive appointments. Strategic Management Journal 28 (3):227-241. [CrossRef]

- Liao, L., T. Lin, and Y. Zhang. 2018. Corporate Board and Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics 150 (1):211-225. [CrossRef]

- Liao, L., L. Luo, and Q. Tang. 2015. Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. The British Accounting Review 47 (4):409-424. [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M., and J. W. Lorsch. 1992. A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance. The Business Lawyer 48 (1):59-77.

- Liu, C. 2018. Are women greener? Corporate gender diversity and environmental violations. Journal of Corporate Finance 52:118-142. [CrossRef]

- Lock, I., and P. Seele. 2016. The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 122:186-200. [CrossRef]

- M. Shamil, M., J. M. Shaikh, P.-L. Ho, and A. Krishnan. 2014. The influence of board characteristics on sustainability reporting. Asian Review of Accounting 22 (2):78-97. [CrossRef]

- Malik, F., F. Wang, M. A. Naseem, A. Ikram, and S. Ali. 2020. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Related to CEO Attributes: An Empirical Study. SAGE Open 10 (1):2158244019899093.

- Malik, N. 2014. Corporate social responsibility and development in Pakistan: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Mallin, C., G. Michelon, and D. Raggi. 2013. Monitoring Intensity and Stakeholders’ Orientation: How Does Governance Affect Social and Environmental Disclosure? Journal of Business Ethics 114 (1):29-43.

- Mathuva, D. 2015. The determinants of forward-looking disclosures in interim reports for non-financial firms: Evidence from a developing country. [CrossRef]

- McGraw, P., and A. Katsouras. 2010. A review and analysis of csr practices in Australian second tier private sector firms. Employment Relations Record 10 (1):1-23.

- Michelon, G., S. Pilonato, and F. Ricceri. 2015. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33:59-78. [CrossRef]

- Momin, M. A., and L. D. Parker. 2013. Motivations for corporate social responsibility reporting by MNC subsidiaries in an emerging country: The case of Bangladesh. The British Accounting Review 45 (3):215-228. [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M. B., A. Khan, and N. Subramaniam. 2015. Firm characteristics, board diversity and corporate social responsibility. Pacific Accounting Review (Emerald Group Publishing Limited) 27 (3):353.

- Nandi, S., and S. Ghosh. 2013. Corporate governance attributes, firm characteristics and the level of corporate disclosure: Evidence from the Indian listed firms. Decision Science Letters 2 (1):45-58. [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M. A., R. U. Rehman, A. Ikram, and F. Malik. 2017. Impact of board characteristics on corporate social responsibility disclosure. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 33 (4):801-810.

- Nekhili, M., H. Nagati, T. Chtioui, and A. Nekhili. 2017. Gender-diverse board and the relevance of voluntary CSR reporting. International Review of Financial Analysis 50:81-100. [CrossRef]

- Ningtyas, C. E., and S. P. Sari. 2023. Board Diversity of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure in Infrastructure Companies Listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. International Journal of Latest Research in Humanities and Social Science (IJLRHSS) 6 (6):325-330.

- Ntim, C., and T. Soobaroyen. 2013. Corporate Governance and Performance in Socially Responsible Corporations: New Empirical Insights from a Neo-Institutional Framework. Corporate Governance: An International Review 21 (5):468-494. [CrossRef]

- Omair Alotaibi, K., and K. Hussainey. 2016. Determinants of CSR disclosure quantity and quality: Evidence from non-financial listed firms in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 13 (4):364-393. [CrossRef]

- Pearce II, J. A., and J. P. Doh. 2005. The high impact of collaborative social initiatives. MIT Sloan Management Review.

- Peng, X., Z. Yang, J. Shao, and X. Li. 2021. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility disclosure of multinational corporations. Applied Economics 53 (42):4884-4898. [CrossRef]

- Pham Hanh Thi, S., and T. Tran Hien. 2019. Board and corporate social responsibility disclosure of multinational corporations. Multinational Business Review 27 (1):77-98.

- Post, C., N. Rahman, and E. Rubow. 2011. Green Governance: Boards of Directors’ Composition and Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility. Business & Society 50 (1):189-223. [CrossRef]

- Powell, G. N., and D. A. Butterfield. 2002. Exploring the influence of decision makers' race and gender on actual promotions to top management. Personnel Psychology 55 (2):397-428. [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M. C., and I. Gallego-Álvarez. 2019. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management 26 (3):612-627. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A., P. Bezemer, A. Zattoni, M. Huse, F. Van den, and H. Volberda. 2009. Boards of Directors' Contribution to Strategy: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review 17 (3):292-306. [CrossRef]

- Rao, K., and T. Carol. 2016. Board diversity and CSR reporting: An Australian study. Meditari Accountancy Research 24 (2):182-210.

- Rao, K., T. Carol, and L. Lester. 2012a. Corporate governance and environmental reporting an Australian study. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 12 (2):143-163.

- Rao, K., and C. Tilt. 2016. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Diversity, Gender, Strategy and Decision Making. Journal of Business Ethics 138 (2):327-347. [CrossRef]

- Rao, K., C. Tilt, and L. Laurence. 2012b. Corporate governance and environmental reporting an Australian study. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 12 (2):143-163.

- Rezaee, Z., M. Alipour, O. Faraji, M. Ghanbari, and B. Jamshidinavid. 2021. Environmental disclosure quality and risk: the moderating effect of corporate governance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 12 (4):733-766. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, Z., C. Cullinan, J. Zhang, and F. Wang. 2020. Institutional Ownership and Value Relevance of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 12 (6):2311. [CrossRef]

- Rob, G., K. Reza, and L. Simon. 1995. Corporate social and environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 8 (2):47-77.

- Rupley, K. H., D. Brown, and R. S. Marshall. 2012. Governance, media and the quality of environmental disclosure. Journal of accounting and public policy 31 (6):610-640.

- Said, R., Y. Hj Zainuddin, and H. Haron. 2009a. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Social Responsibility Journal 5 (2):212-226. [CrossRef]

- Said, R., Y. Zainuddin, and H. Haron. 2009b. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Social Responsibility Journal 5 (2):212-226. [CrossRef]

- Scamardella, F. 2015. Law, globalisation, governance: emerging alternative legal techniques. The Nike scandal in Pakistan. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 47 (1):76-95.

- SECP. 2017. Public Sector Companies CG rules.

- Shahbaz, M., A. S. Karaman, M. Kilic, and A. Uyar. 2020. Board attributes, CSR engagement, and corporate performance: what is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 143:111582.

- Shahid, H. M., R. Waseem, H. Khan, F. Waseem, M. J. Hasheem, and Y. Shi. 2020. Process Innovation as a Moderator Linking Sustainable Supply Chain Management with Sustainable Performance in the Manufacturing Sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 12 (6):2303. [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A., Y. Qiu, and G. Trojanowski. 2016. Board Attributes, Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy, and Corporate Environmental and Social Performance. Journal of Business Ethics 135 (3):569-585. [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M., N. Abdullah, and A. Fatima. 2014. Determinants of environmental reporting quality in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting 22 (1).

- Sundarasen, S. D. D., T. Je-Yen, and N. Rajangam. 2016. Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J. F., and A. O. Carvalho. 2023. Corporate governance in SMEs: a systematic literature review and future research. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society. [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S., E. B. Couto, and P. M. Francisco. 2016. Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. Journal of Management & Governance 20 (3):447-483. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. G., R. S. Kim, A. M. Aloe, and B. J. Becker. 2017. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 39 (2):81-90. [CrossRef]

- Umair, S., A. Björklund, and E. E. Petersen. 2015. Social impact assessment of informal recycling of electronic ICT waste in Pakistan using UNEP SETAC guidelines. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 95:46-57. [CrossRef]

- UN. 2023. Summary report of country-wide women’s consultations.

- Vives, A. 2008. Corporate Social Responsibility: The role of law and markets and the case of developing countries. Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 83:199.

- WB. 2022. Country Climate and Development Report.

- WEF. 2022. Global Gender Gap Report.

- Wilmshurst, T. D., and G. R. Frost. 2000. Corporate environmental reporting: A test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 13 (1):10-26.

- Wirba, A. V. 2023. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Government in promoting CSR. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R., and P. Hąbek. 2016. Quality Assessment of CSR Reports–Factor Analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 220:541-547.

- Yasser, Q. R., A. Al Mamun, and I. Ahmed. 2017. Corporate Social Responsibility and Gender Diversity: Insights from Asia Pacific. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24 (3):210-221. [CrossRef]

- Yekini, K. C., I. Adelopo, P. Andrikopoulos, and S. Yekini. 2015. Impact of board independence on the quality of community disclosures in annual reports. Accounting Forum 39 (4):249-267. [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, A. 2011. Who Should Control a Corporation? Toward a Contingency Stakeholder Model for Allocating Ownership Rights. Journal of Business Ethics 103 (2):255-274. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., H. Zhu, and b. Ding. 2013. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: An Empirical Investigation in the Post Sarbanes-Oxley Era. Journal of Business Ethics 114 (3):381-392. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Y. G. Shan, and M. Chang. 2020. Can CSR Disclosure Protect Firm Reputation During Financial Restatements? Journal of Business Ethics.

Table 1.

Distribution of PSX 100 sample.

Table 1.

Distribution of PSX 100 sample.

| Industry group |

Initial sample |

Final sample |

| Consumer Discretionary |

9 |

8 |

| Consumer Staples |

3 |

3 |

| Energy |

8 |

7 |

| Financials |

31 |

30 |

| Health Care |

2 |

2 |

| Industrials |

7 |

6 |

Telecommunications, &

IT Services |

5 |

5 |

| Materials |

22 |

21 |

| Real Estate |

3 |

2 |

| Utilities |

10 |

10 |

| Total |

100 |

94 |

Table 2.

CSR Disclosure QUALITY Index and calculation mechanism.

Table 2.

CSR Disclosure QUALITY Index and calculation mechanism.

Table 3.

Operational definitions of independent and control variables.

Table 3.

Operational definitions of independent and control variables.

| Independent Variables |

Symbol |

Measurement |

Gender Diversity |

Gendrdiv |

Proportion of female board of directors to total directors in the board |

Board Independence |

Independ |

Proportion of independent and non-

executive directors to total directors in the board |

Female Chairperson |

Femchair |

1 if the chairperson of the board is female, 0 otherwise |

Female CEO |

FemCEO |

1 if the CEO is a female, 0 otherwise. |

Board Size |

Bsize |

Total number of board members |

| Control Variables |

|

|

Profitability:

Return on Assets (ROA) |

Prof |

ROA = Earnings after-tax/Total assets |

Company Leverage:

Financial Leverage |

FrmLiq |

Total debt / Total assets |

Company Liquidity:

Current Ratio |

FrmLiq |

Current assets/Current liabilities |

Company Size |

Comsize |

Natural log of Total assets at the end of the year |

Industry Classification |

IND |

Dummy variables for the ten industry

groups of Global Industry Classification scheme |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of independent and control variables.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of independent and control variables.

| |

Mean |

Median |

Standard

Deviation |

Min. |

Max. |

CSR

Disclosure Quality |

1.76 |

1.68 |

0.44 |

0.63 |

3.06 |

| Gender Diversity |

0.1 |

0 |

0.13 |

0 |

0.43 |

| Board Independence |

0.32 |

0.3 |

0.12 |

0 |

0.5 |

| Female Chairperson |

0.04 |

0 |

0.2 |

0 |

1 |

Female CEO |

0.02 |

0 |

0.11 |

0 |

1 |

Board Size |

8.51 |

8 |

1.99 |

6.5 |

15.5 |

Profit |

2.58 |

1.26 |

9.5 |

–49.42 |

26.85 |

Leverage |

0.24 |

0.18 |

0.28 |

0 |

1.78 |

Liquidity |

1.38 |

1.07 |

1.48 |

0.09 |

10.24 |

| Company Size |

7.7 |

7.55 |

0.91 |

2.81 |

9.43 |

Table 6.

Pearson correlation coefficient results.

Table 6.

Pearson correlation coefficient results.

Table 7.

Collinearity Statistics of sample.

Table 7.

Collinearity Statistics of sample.

| |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| Gender Diversity |

.739 |

1.353 |

| Board Independence |

.803 |

1.245 |

| Female Chairperson |

.866 |

1.155 |

| Female CEO |

.951 |

1.052 |

| Board Size |

.803 |

1.246 |

Table 8.

Summary of Regression Results.

Table 8.

Summary of Regression Results.

| Variable |

Coefficients |

p-value |

| Independent variables |

|---|

| Gender Diversity |

0.443 |

0.200 |

| Board Independence |

–0.395 |

0.256 |

| Female Chairperson |

–0.424*** |

0.009 |

| Female CEO |

–0.611*** |

0.008 |

| Board Size |

0.020 |

0.446 |

| Control variables |

| Profit |

0.015** |

0.020 |

| Leverage |

–0.230 |

0.113 |

| Liquidity |

–0.013 |

0.625 |

| Company Size |

0.125** |

0.056 |

| Industry |

| Consumer Staples |

–0.382 |

0.259 |

| Consumer Discretionary |

–0.323* |

0.082 |

| Energy |

–0.091 |

0.728 |

| Financials |

–0.520*** |

0.003 |

| Health Care |

0.000 |

0.00 |

| Industrials |

–0.170 |

0.392 |

| Materials |

–0.244 |

0.165 |

| Real Estate |

–0.456** |

0.037 |

| Telecommunication and IT |

–0.525*** |

0.012 |

| Utilities |

–0.429** |

0.037 |

| Constant |

1.141 |

|

| R square |

0.47 |

|

| ***, ** and * indicate that the variable is significant at 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10, respectively |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).