Submitted:

09 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

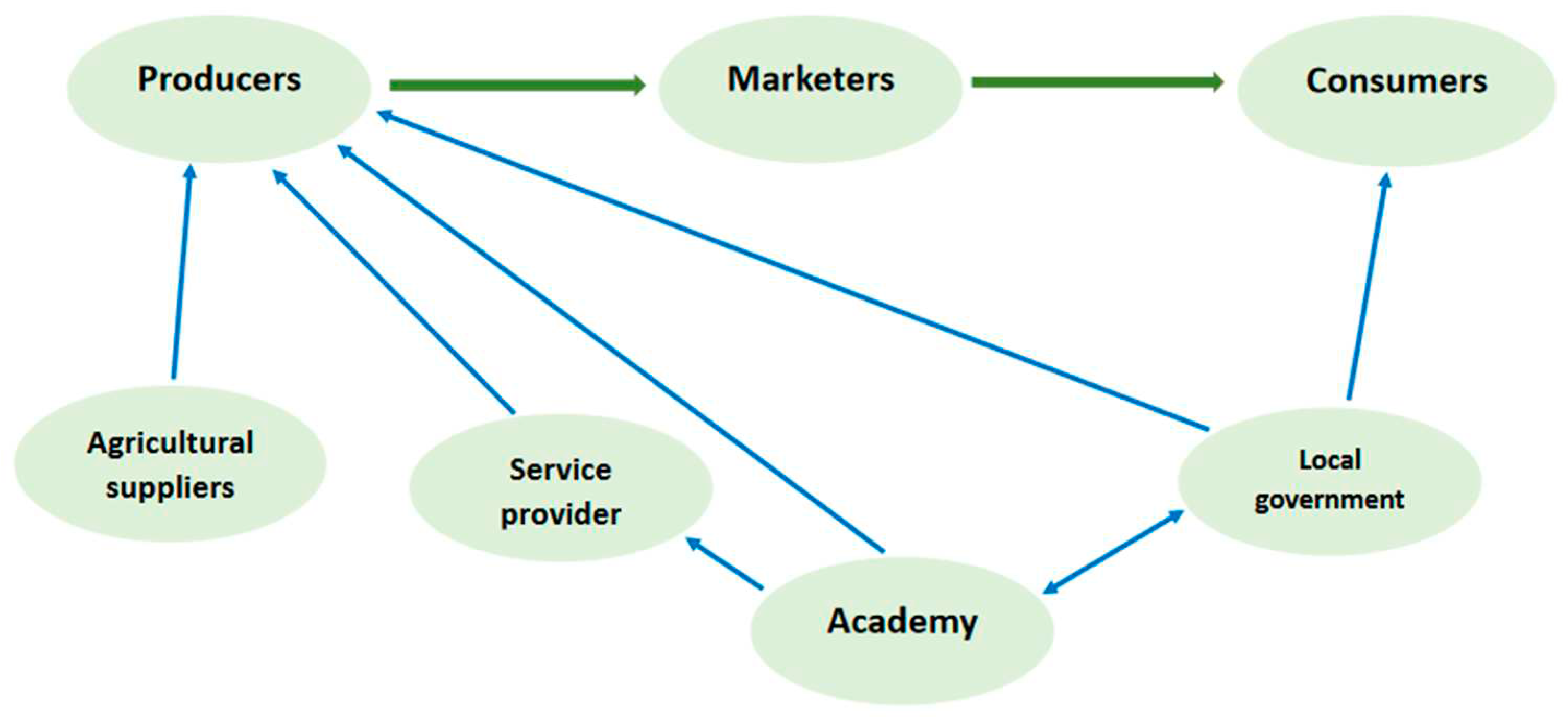

1.1. The guinea pig value chain in Jauja and its actors

1.2. The importance of projects for sustainable rural development

1.3. Project management competencies and their influence on institutional capacities

2. Materials and Methods

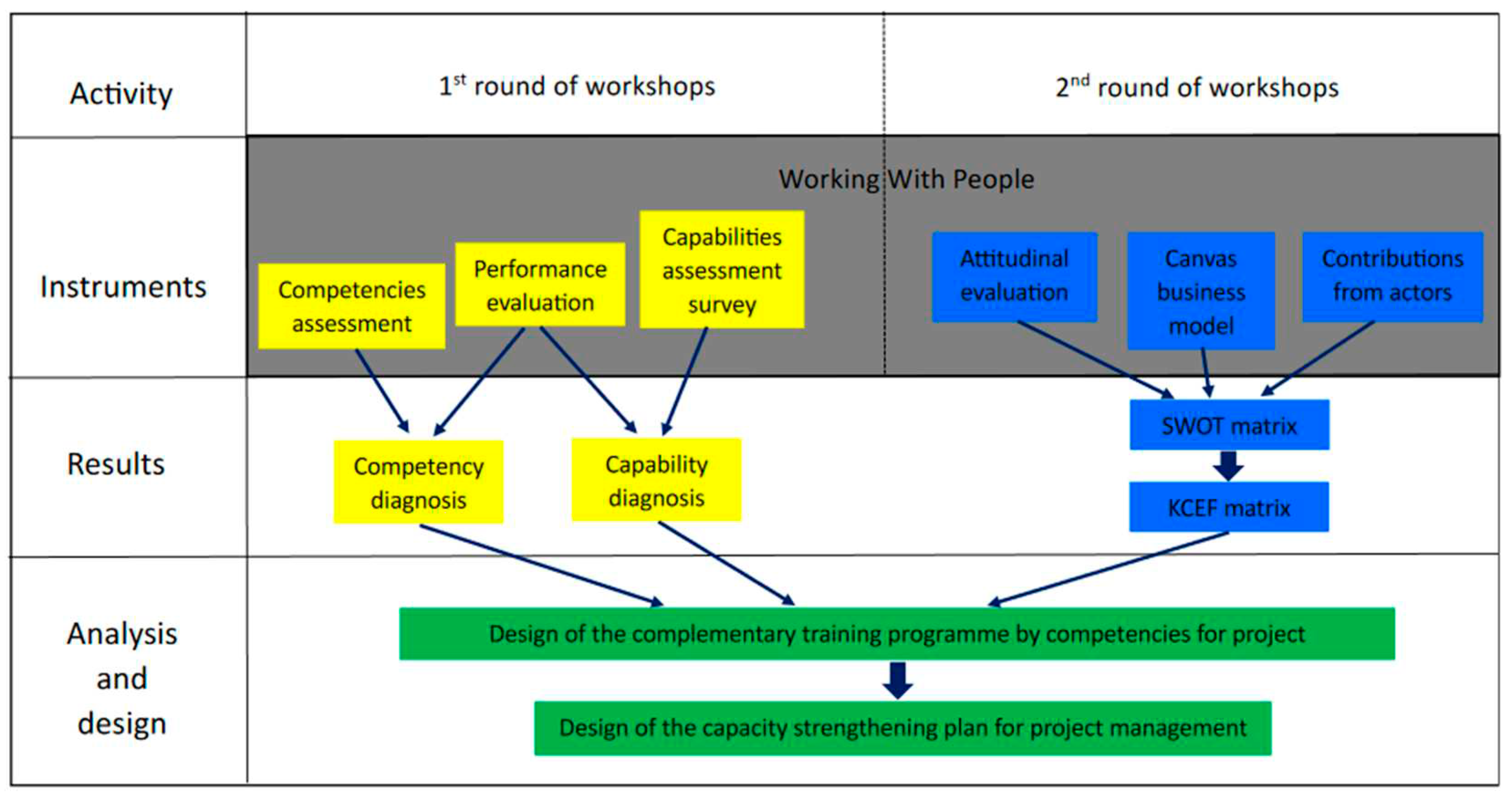

2.1. Stage 1: Diagnosis of competencies and capabilities in project management in actors of the guinea pig value chain, in Jauja

2.2. Stage 2: Evaluation of attitude, business opportunity and contributions to improving training

2.3. Stage 3: Analysis of information and design of a complementary training programme by competencies connected to a plan to improve institutional capabilities

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. How prepared are the actors in the guinea pig value chain for the management of sustainable rural development projects?

3.1.1. Ethical-social dimension

3.1.2. Technical-entrepreneurial dimension

3.1.3. Political-contextual dimension

3.2. Design of an innovative competencies development programme connected to a capacity-strengthening plan for actors in the Jauja guinea pig value chain

3.2.1. Subsubsection

- First bullet;

- Second bullet;

- Third bullet.

- First item;

- Second item;

- Third item.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fedele, G.; Donatti, C. I.; Bornacelly, I.; Hople, D. G. Nature-dependent people: Mapping human direct use of nature for basic needs across the tropics. Global Environmental Change 2021, 71, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, S.; Adshead, D.; Fay, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Harvey, M.; Meller, H.; O´Reagan, N.; Rozenberg, J.; Watkins, G.; Hall, J. W. Infrastructure for sustainable development. Nature Sustainability 2019, 2, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Pobreza monetaria alcanzó al 30.1% de la población del país durante el año 2020. Nota de prensa N° 067. 2021. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/noticias/np_067_2021.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- López, I. Sobre el desarrollo sostenible y la sostenibilidad: conceptualización y crítica. Revista Castellano-Manchega de Ciencias Sociales 2015, 20, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cantú, J. B.; Fenner, G. M. San Cristóbal de las Casas: Las consecuencias ambientales de un crecimiento ambicioso y descontrolado. Diversidad 2020, 18, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni, E.; Fabietti, G. What Is Sustainability? A Review of the Concept and Its Applications. In Integrating Reporting, Busco, C., Frigo, M., Riccaboni, A., Quattrone, P., Eds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, R.; De los Ríos, I.; Huamán, A. The CFS-IRA principles as instruments for the management of rural development projects. The case of the central highlands of Perú. In Proceedings from the XXVI International Congress of Project Management and Engineering, Terrassa, España, 5-8 July 2022; pp. 1632-1644.

- Scrimshaw, N. Malnutrition, brain development, learning and behavior. Nutrition Research 1998, 18, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Migraciones internas en el Perú. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones: Lima, Perú. 2015. Available online: https://repository.iom.int/bitstream/handle/20.500.11788/1490/PER-OIM_009.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Trivelli, C.; Escobal, J.; Revesz, B.; Desarrollo Rural en la Sierra. Aportes para el Debate. CIPCA, GRADE, IEP, CIES. Lima. 2009. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51460-4 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Municipalidad Provincial de Jauja. Plan de Desarrollo Local Concertado 2019–2030. 2019. Available online: http://www.munijauja.gob.pe/files/abe852a810334063afa7fb29343997d7.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Jiménez, R.; Huamán, A. Manual para el manejo de reproductores híbridos especializados en producción de carne. INCAGRO-ACRICUCEN-UNMSM: El Mantaro, Perú, 2020; 175 p.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Resultados Definitivos de los Censos Nacionales 2017. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1576/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Chauca, L. Producción de cuyes (Cavia porcellus). Estudio FAO: producción y sanidad animal, 138. FAO: Roma, Italy, 1997; 80 p.

- Aliaga, L.; Moncayo, R.; Rico, E.; Caycedo, A. Producción de cuyes. Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Católica Sedes Sapientiae: Lima, 2009; 808 p.

- Chirinos, O.; Muro, K. , Álvaro Concha, W., Otiniano, J., Quezada, J. C., & Ríos, V. Crianza y comercialización de cuy para el mercado limeño; ESAN: Lima, 2008; 187 p.

- Menconi, M. E.; Grohmann, D.; Mancinelli, C. European farmers and participatory rural appraisal: A systematic literature review on experiences to optimize rural development. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R.; De los Ríos, I.; San Martín, F.; Calle, S. Creation of Local Action Groups for rural development in Peru: Perspectives from the CDR El Mantaro, UNMSM. In Proceedings of the XXV International Congress of Project Management and Engineering, Alcoy, Spain, 6–9 July 2021; pp. 1862–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín, F.; Calle, S.; Huamán, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercher, N. The role of Actors in Social Innovation in Rural Areas. Land 2022, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.; Szczepanek, T. Projects and Programmes as value creation processes: A new perspective and some practical implications. International Journal of Project Management 2008, 26, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. The LEADER community initiative as rural development model: Application in the capital region of Spain. Agrociencia 2005, 39, 697–708. Available online: https://www.agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/434/434 (accessed on 04 January 2023).

- Rochedy, L.; Salvo, M. Viabilidad de la metodología LEADER para la gestión del desarrollo rural en Perú. In Proceedings from the XIV International Congress on Project Engineering, Madrid, AEIPRO, 2010; pp. 1891-1905.

- Navarro, F. A.; Cejudo, E.; Cañete, J. A. A long-run analysis of neoendogenous rural development policies: The persistence of business created with the support of leader and proder in three districts of Andalucia (Spain) in the 1990s. Ager 2018, 25, 189–219. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J. The LEADER initiative as a model of rural development: Application to some territories of Mexico. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 609–624, Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1405- 31952011000500007&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 22 January 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Stratta, R.; De los Ríos, I.; López, M. Developing Competencies for Rural Development Project Management through Local Action Groups: The Punta Indio (Argentina) Experience. In International Development; Appiah-Opoku, S., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2017; pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Quispe, A. ; La necesidad de formación de capacidades para la gestión del desarrollo rural territorial. Región y Sociedad 2006, 18, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ivey, J. L.; Smithers, J.; De Loë, R. C.; Kreutzwiser, R. D. Community Capacity for Adaptation to Climate-Induced Water Shortages: Linking Institutional Complexity and Local Actors. Environmental Management 2004, 33, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.S. Competencias blandas en los gerentes de proyectos de las organizaciones. RES NON VERBA REVISTA CIENTÍFICA 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copola, F.; Aparecida, D.; Leme, A. The role and characteristics of hybrid approaches to project management in the development of technology-based products and services. Project Management Journal 2021, 52, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, A. Una ruta metodológica para evaluar la capacidad institucional. Política y cultura 2008, 30, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- [IPMA] Asociación Española en Dirección e Ingeniería de Proyectos. Bases para la competencia individual en Dirección de Proyectos, Programas y Carteras de Proyectos. IPMA: Valencia, España, 2017, 428 p. Available online: https://ipmamexico.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ICB4.pdf (accessed on 06 January 2023).

- Diez-Silva H., M.; Pérez-Ezcurdia, M. A.; Gimena, F. N.; Montes-Guerra, M. I. Medición del desempeño y éxito en la dirección de proyectos. Perspectiva del manager público. Revista EAN 2012, 73, 60–79. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-81602012000200005 (accessed on 06 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, K.; West, J.; Skellern, K.; Josserand, E. Evolving a value chain to an open innovation ecosystem: Cognitive engagement of stakeholders in customizing medical implants. California Management Review 2021, 63, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.; Soares, I. Benefits and barriers concerning demand response stakeholder value chain: A systematic literature review. Energy 2023, 280, 128065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, G. B.; Saroli, L. G. Sustainable value chain management based on dynamic capabilities in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The International Journal of Logistics Management 2021, 32, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, P. J.; Carlson, S. L.; Zdorkowski, G. A.; Honeyman, M. S. Reducing food insecurity in developing countries through meat production: the potential of the guinea pig (Cavia porcellus). Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2009, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R. Uso de insumos agrícolas locales en la alimentación de cuyes en valles interandinos. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Producción Animal 2007, 15(Supl. 1), 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, A. F. Evaluación de la producción y comercialización de cuyes en el marco del proyecto Procuy en el distrito de El Mantaro-Jauja. Tesis de Ingeniero Zootecnista. Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Perú, 2014.

- Rodriguez, T. L. Analisis situacional y prospective de pequeños productores de cuyes asociados del valle del Mantaro. Máster. Sci Thesis, Universidad Agraria La Molina, Lima, Perú, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Escobal, J.; Ponce, C.; Hernández Asensio, R. Límites a la articulación a mercados dinámicos en entornos de creciente vulnerabilidad ambiental: el caso de la dinámica territorial rural en la Sierra de Jauja, Junín. Documento de Trabajo N° 69. Programa Dinámicas Territoriales Rurales. Rimisp: Santiago, Chile, 2011.

- Aliaga, H. Organización de la cadena productiva del cuy en el valle del Mantaro proyectado al mercado nacional e internacional. Tesis de Doctor en Administración de Negocios Globales. Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, Perú, 2016.

- Espinoza, D.; Salina, M. F. Eficiencia en la gestión empresarial de las asociaciones de mujeres productoras de cuy, provincia de Jauja, período 2014-2015. Tesis de Economista. Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Perú, 2016.

- Ahumada, J. L.; Cheng, D. G.; Mantilla, A. A. Desarrollo del mercado de carne de cuy en Lima Metropolitana. Tesis de Bachiller en Agronegocios. Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Lima, Perú, 2016.

- Valenzuela, R. N.; Valdez, W. P. Fuentes de financiamiento del estado para organizaciones de productores agropecuarios en el Perú. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 2021, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Huamán, A. Informe final de proyecto: Innovación en el enfoque de competencias para la formación de técnicos extensionistas en producción de cuyes. UNMSM-INCAGRO: Jauja, Perú. 2010.

- Müller, R. , & Turner, J. R. Matching the project manager’s leadership style to project type. International Journal of Project Management 2007, 25, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, W. F.; Pino, R. M.; Amaya, A. A. Factores que impactan en los criterios de éxito de los proyectos en Perú y Ecuador: el rol moderador de las competencias del director de proyecto. Información tecnológica 2021, 32, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, M.; Paasivaara, L. Shared Human Capital in Project Management: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Project Management Journal 2011, 42, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. W.; Adams, J. D.; Amjad, A. A. The relationship between human capital and time performance in project management: A path analysis. International Journal of Project Management 2007, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A. J. G.; Schipper, R. P. J. Sustainability in project management: A literature review and impact analysis. Social Business 2014, 4, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J. A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G. P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S. R.; Chapin, F. S.; Coe, M. T.; Daily, G. C.; Gibbs, H. K.; Helkowski, J. H.; Holloway, T.; Howard, E. A.; Kucharik, C. J.; Monfreda, C.; Patz, J. A.; Prentice, I. C.; Ramankutty, N; Snyder, P. K. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems. Committee on World Food Security. 2014. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/au866e/au866e.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, C. J. Sustainable development: concept, value and practice. Third World Planning Review 1995, 17, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. , & Hardy, D. Addressing poverty and inequality in the rural economy from a global perspective. Applied Geography 2015, 61, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schafft, K. A. Rural Education As Rural Development: Understanding the Rural School-Community Well-Being Linkage in a 21st-Century Policy Context. Peabody Journal of Education 2016, 91, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Hoffmann, N. The Leader Programme as an Impulse for New Projects in Rural Areas. Quaestiones Geographicae 2018, 37, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Valverde, F.; Labianca, M.; Cejudo-García, E.; De Rubertis, S. Social Innovation in Rural Areas of the European Union Learnings from Neo-Endogenous Development Projects in Italy and Spain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J. J.; Esparcia, J. Diagnosis of Rural Development Processes Based on the Stock of Social Capital and Social Networks: Approach from E-I Index. Land 2023, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in rural development projects: A proposal from social learning. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I. From “Putting the Last First” to “Working with People” in Rural Development Planning: A Bibliometric Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Building institutional capacity in rural Northern Ireland: the role of partnership governance in the LEADER II programme. Journal of Rural Studies 2004, 20, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M. C.; Arfini, F.; Guareschi, M. When Higher Education Meets Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: Lessons Learned from a Community–University Partnership. Social Sciences 2022, 11, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatkin-Troitschanskaiaa, O.; Shavelsonb, R. J.; Kuhn, C. The international state of research on measurement of competency in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 2015, 40, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, G. F. Observaciones al enfoque por competencias y su relación con la calidad educativa. Sophia, colección de Filosofía de la Educación 2022, 32, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, R. What is wrong with competency research? Two propositions. Asian Social Science 2015, 11, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos, I.; Turek, A.; Afonso, A. Project management competencies for regional development in Romania: analysis from “Working with People” model. Procedia Economics and Finance 2014, 8, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Beemt, A.; Vázquez-Villegas, P.; Gómez Puente, S.; O’Riordan, F.; Gormley, C.; Chiang, F.-K.; Leng, C.; Caratozzolo, P.; Zavala, G.; Membrillo-Hernández, J. Taking the Challenge: An Exploratory Study of the Challenge-Based Learning Context in Higher Education Institutions across Three Different Continents. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [SIDA] Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. The Octagon-A tool for the assessment of strengths and weaknesses in NGOs. Estocolmo, Suecia: SIDA. 2002. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/the-octagon_1742.pdf/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Rosas, A. Capacidad institucional: revisión del concepto y ejes de análisis. Documentos y Aportes en Administración Pública y Gestión Estatal: DAAPGE 2019, 19, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, D. Desarrollo, sostenibilidad y capacidades: una trilogia indesligable. Cuadernos de Difusión 2007, 12, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobelem, A. Institutional capacity analysis and development system (ICADS). Public Sector Management Division, Technical Department Latin America and the Caribbean Region of the World Bank. LATPS Occasional Paper Series N° 9, 1992.

- Oszlak, O.; Orellana, E. El análisis de la capacidad institucional: aplicación de la metodología SADCI. Documento de trabajo, 2001.

- Hyder, A.A.; Zafar, W.; Ali, J.; Ssekubugu, R.; Ndebele, P.; Kass, N. Evaluating institutional capacity for research ethics in Africa: a case study from Botswana. BMC Med Ethics 2013, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza, S.; , Mamani, E. A. Formulación de un plan estratégico institucional, para el fortalecimiento de la fundación TEKO KAVI. Tesis de Licenciado en Administración de Empresas, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Bolivia, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.umsa.bo/handle/123456789/22418 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Deutsch-Feldman, M.; Ali, J.; Kass, N.; Phaladze, N.; Michelo, C.; Sewankambo, N.; Hyder, A. A. Improving institutional research ethics capacity assessments: lessons from sub-Saharan Africa. Global Bioethics 2020, 31, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenilla, M. Innovación social y capacidad institucional en Latinoamérica. Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 2017, 67, 33–68. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Institutional Quality, Governance and Progress towards the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, R. R. Impacto del asesoramiento técnico y organizativo en los sistemas de producción de la asociación de mujeres productoras de Yauli-Jauja. Tesis de Magister Scientiae, Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Perú, 2016.

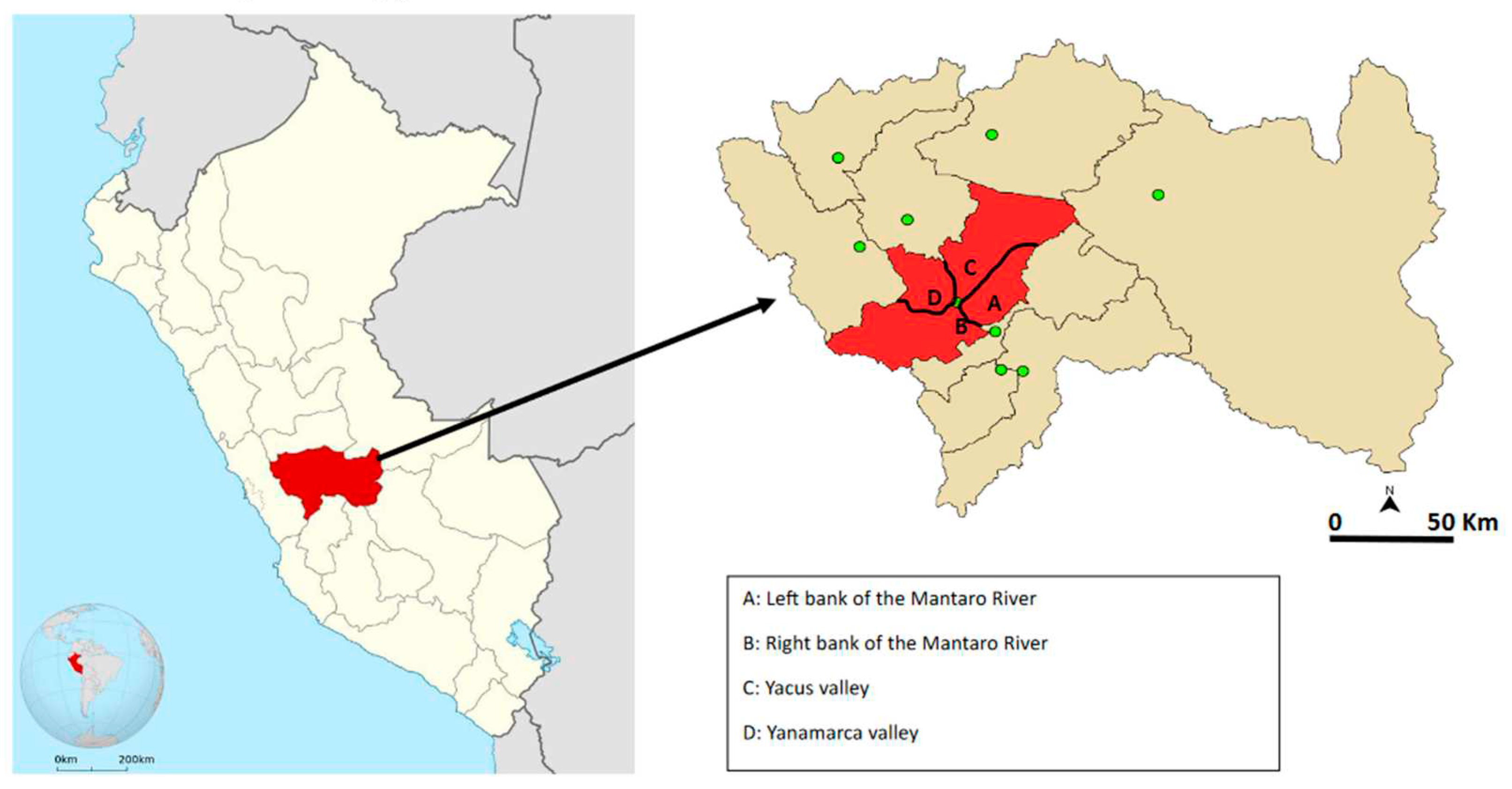

- Provincia de Jauja. Wikipedia. Available online: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provincia_de_Jauja (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Likert, R. A. Technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol 1932, 22, 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L. J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J. El aprendizaje significativo y la evaluación de los aprendizajes. Investigación educativa 2004, 8, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, L. F.; Montaluisa, Á.; Salas, E. El aprendizaje significativo y su relación con los estilos de aprendizaje. Revista Anales 2018, 1, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M. El aprendizaje experiencial y las nuevas demandas formativas. Antropología Experimental 2010, 10, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Espinar, E. M.; Vigueras, J. A. El aprendizaje experiencial y su impacto en la educación actual. Revista Cubana de Educación Superior 2020, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D. C. El modelo Canvas en la formulación de proyectos. Cooperativismo & desarrollo 2015, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sparviero, S. The case for a socially oriented business model canvas: The social enterprise model canvas. Journal of social entrepreneurship 2019, 10, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano. L.; Caicedo, J.; Fernández T., Onofre, R. El modelo de negocio: metodología canvas como innovación estratégica para el diseño de proyectos empresariales. Journal of science and research 2019, 4, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Albertus, M.; Espinoza, M.; Fort, R. Land reform and human capital development: Evidence from Peru. Journal of Development Economics 2020, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaifi, B. A.; Noori, S. A. Organizational Behavior: A Study on Managers, Employees, and Teams. Journal of Management Policy and Practice 2011, 12, 88–97. Available online: http://www.na-businesspress.com/jmpp/kaifiweb.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Coloma, E. El impacto del COVID-19 en las mujeres trabajadoras del Perú. ¿Se incrementa la desigualdad y la violencia en el trabajo? Ius Et Praxis 2021, 053, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwir, M.; Safdar, T. "The Rural Woman's Constraints to Participation in Rural Organizations, Journal of International Women's Studies 2013, 14(3), 15. 14.

- Forstner, K. Women´s Group-based work and Rural Gender Relations the Southern Peruvian Andes. Bulletin of Latin American Research 2013, 32, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilela, Z.; Molnar, J. J. Gender and Rural Vitality: Empowerment through Women’s Community Groups*. Rural Sociology 2021, 0, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, A. Sex on the brain: Are gender-dependent structural and functional differences associated with behavior? Journal of Neuroscience Research 2017, 95, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, A. 2000. Reforma institucional. En Desafíos del Desarrollo Rural en el Perú; Trivelli, C., von Hesse, M., Diez, A., del Castillo, L., Eds.; Consorcio de Investigación Económica y Social: Lima, Perú, 2000; pp. 35–54. Available online: https://cies.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/dyp-02.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- García, J. A. La educación emocional, su importancia en el proceso de aprendizaje. Revista Educación 2012, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nungsari, M.; Ngu, K.; Chin, J. W.; Flanders, S. The formation of youth entrepreneurial intention in an emerging economic: the interaction between psychological traits and socioeconomic factors. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 2023, 15, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.; Shutte, A. M. Community leadership development. Community Development Journal 2004, 39, 234.251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D. Relational Leadership and Regional Development: A case study on new agriculture ventures in Uganda. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 2019, 24, 1950010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Espinosa, H.; Ospina-Parra, C. E.; Ramírez-Gómez, C. J.; Toro-González, I. C.; Gallego-Lopera, A.; Piedrahita-Pérez, M. A.; Velásquez-Chica, A.; Gutiérrez-Molina, S.; Flórez-Tuta, N.; Hincapié-Echeverri, O. D.; Romero-Rubio, L. C. Lineamientos para una metodología de identificación de estilos de aprendizaje aplicables al sector agropecuario colombiano. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 2020, 21, e1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.; Harrison, J. “The interrelatedness of formal, non-formal and informal learning: Evidence from labour market program participants”, Australian Journal of Adult Learning 2012, 52(2), pp. 277-309.

- Daza, Y. F. La andragogía como fundamento pedagógico en el modelo de extensión. In Programa de formación en extensión. Orientaciones curriculares; Bernal, L., Ed.; Fundación Centro Internacional de Educación y Desarrollo Humano: Colombia, 2019; pp. 65–76. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yaneth-Daza-Paredes/publication/356082582_Programa_de_formacion_en_extension/links/618b2248d7d1af224bcffe66/Programa-de-formacion-en-extension.pdf#page=66 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Coffey, W. J. , & Polèse, M. The concept of local development: A stages model of endogenous regional growth*. Papers in Regional Science 1984, 55(1), 1–12.

- Friedrich, K. A systematic literature review concerning the different interpretations of the role of sustainability of project management. Manag. Rev. Q 2021, 73, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phélinas, P. Les effets de la formation sur l'emploi en milieu rural péruvien. Mondes en Developpement 2016, 34, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, S.; Ghimire, S.; Upadhyay, M. What Factors in Nepal Account for the Rural–Urban Discrepancy in Human Capital? Evidence from Household Survey Data. Economies 2021, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiskin, M. Situación de las juventudes rurales en América Latina y el Caribe, serie Estudios y Perspectivas - Sede subregional de la CEPAL en México, N° 181 (LC/TS.2019/124-LC/MEX/TS.2019/31). Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): México, 2019.

- Morley, S. Changes in rural poverty in Perú 2004-2012. Latin American Economic Review 2017, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honadle, G. H.; Hannah, J P. Management performance for rural development: packaged training or capacity building. Public Administration and Development 1982, 2, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, K.; Phillips, S.; Dicke, M.; Fredrix, M. Impacts of farmers field schools in the human, social, natural and financial domain: a quantitative review. Food Security 2020, 12, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C. Endogenous development and institutions: Challenges for local development initiatives. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2016, 34, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmano, C. G.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M. L. “It just a matter of culture”: an explorative study on the relationship between training transfer and work performance. Journal of Workplace Learning 2022, 34, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivieso, P. Network organizations: A review on estructural efficiency in business. Espacios 2013, 34, 16. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a13v34n07/13340716.html (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Morrison, T. H. Developing a regional governance index: The institutional potential of rural regions. Journal of Rural Studies 2014, 35, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification criteria | Total |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 9 |

| Male | 3 |

| Mixed | 34 |

| Type of actor | |

| Producer | 19 |

| Marketer | 9 |

| Consumer | 3 |

| Academy | 5 |

| Local government | 6 |

| Service provider | 2 |

| Agricultural suppliers | 2 |

| Zone | |

| Left bank of the Mantaro river | 16 |

| Right bank of the Mantaro river | 6 |

| Yacus valley | 14 |

| Yanamarca valley | 3 |

| All | 7 |

| Number of members | |

| 1 to 10 members | 20 |

| More than 10 members | 26 |

| Years of activity | |

| 1 to 3 years | 13 |

| Over 3 years | 33 |

| Total | 46 |

| Classification criteria | Competency values (1–5) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perspective | Person | Practice | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 3.18 | 3.28 | 2.75 | 3.01 |

| Male | 2.73 | 3.62 | 2.28 | 2.83 |

| Mixed | 2.61 | 2.96 | 2.42 | 2.65 |

| Type of actor | ||||

| Producer | 2.94 | 3.21 | 2.66 | 2.9 |

| Marketer | 2.47 | 2.83 | 1.85 | 2.31 |

| Consumer | 2.67 | 2.5 | 2.21 | 2.39 |

| Academy | 2.42 | 2.92 | 2.51 | 2.64 |

| Local government | 2.83 | 3.34 | 2.85 | 3.02 |

| Service provider | 3.4 | 4.15 | 3.5 | 3.71 |

| Agricultural suppliers | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.65 | 1.84 |

| Zone | ||||

| Left bank of the Mantaro river | 2.73 | 3.19 | 2.81 | 2.93 |

| Right bank of the Mantaro river | 2.75 | 3.38 | 2.24 | 2.74 |

| Yacus valley | 2.52 | 2.62 | 2.08 | 2.35 |

| Yanamarca valley | 2.78 | 2.89 | 2.18 | 2.54 |

| All | 3.1 | 3.48 | 2.81 | 3.1 |

| Number of members | ||||

| 1 to 10 members | 2.64 | 2.98 | 2.32 | 2.61 |

| More than 10 members | 2.79 | 3.13 | 2.59 | 2.82 |

| Years of activity | ||||

| 1 to 3 years | 2.93 | 3.09 | 2.46 | 2.76 |

| Over 3 years | 2.65 | 3.06 | 2.48 | 2.72 |

| General Average | 2.73 | 3.07 | 2.47 | 2.73 |

| IPMA Competencies | Institutional Capacities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | Structure | Implementation of activities | Relevance of activities | Professional skills | Systems | Acceptance | Relations | |

| Perspective | ||||||||

| Strategy | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Governance, structure and processes | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Compliance, standards and regulations | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Power and interest | X | X | ||||||

| Culture and values | X | X | X | |||||

| Person | ||||||||

| Self-reflection and self-management | X | X | ||||||

| Personal integrity and reliability | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal communication | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Relationships and participation | X | X | X | |||||

| Leadership | X | X | ||||||

| Teamwork | X | X | ||||||

| Conflict and crisis | X | X | X | |||||

| Ingenuity | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Negotiation | X | X | X | |||||

| Orientation to results | X | X | X | |||||

| Practice | ||||||||

| Project design | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Requirements and objectives | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Scope | X | X | ||||||

| Time | X | X | ||||||

| Organization and information | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Quality | X | X | X | |||||

| Finance | X | X | ||||||

| Resources | X | X | X | |||||

| Provisioning | X | X | X | |||||

| Planification and control | X | X | X | |||||

| Risk and opportunity | X | X | X | |||||

| Stakeholders | X | X | ||||||

| Change and transformation | X | X | X | |||||

| Classification criteria | Institutional Capacities | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identtiy | Structure | Implementation of activities | Relevance of activities | Professional skills | Systems | Acceptance | Relations | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 2.35 | 3.71 | 3.1 | 2.14 | 2.31 | 2.75 | 1.88 | 2.21 | 2.55 |

| Male | 2.17 | 3 | 2.67 | 1.83 | 2.67 | 3.17 | 3 | 2 | 2.56 |

| Mixed | 2.85 | 3.71 | 3.09 | 2.72 | 2.71 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.49 | 3.01 |

| Type of actor | |||||||||

| Producer | 2.78 | 3.93 | 3.28 | 2.57 | 3.37 | 2.78 | 2.39 | 2.28 | 2.8 |

| Marketer | 2.06 | 2.78 | 2.39 | 2.11 | 1.89 | 2.83 | 2.83 | 1.89 | 2.35 |

| Consumer | 1.5 | 3.5 | 2 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 3.67 | 2.33 | 2.67 | 2.54 |

| Academy | 4.2 | 4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.75 |

| Local government | 2.67 | 3.58 | 3.33 | 2.5 | 3.25 | 4.25 | 3.5 | 2.92 | 3.25 |

| Service provider | 3.25 | 5.5 | 4.75 | 2.75 | 4.5 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 2.25 | 3.81 |

| Agricultural suppliers | 2.5 | 3 | 2.25 | 2 | 2.5 | 4.25 | 2.25 | 2 | 2.59 |

| Zone | |||||||||

| Left bank of the Mantaro river | 3.33 | 3.77 | 3.56 | 3.09 | 2.89 | 3.84 | 3.16 | 2.59 | 3.28 |

| Right bank of the Mantaro river | 2.92 | 4.33 | 2.75 | 2.67 | 2.42 | 3.33 | 2.58 | 2.92 | 2.99 |

| Yacus valley | 1.71 | 2.86 | 2.32 | 1.86 | 2.36 | 2.29 | 2.29 | 1.96 | 2.21 |

| Yanamarca valley | 2 | 3 | 2.33 | 1.58 | 1.92 | 1.75 | 1.96 | 1.79 | 2.04 |

| All | 3.36 | 4.79 | 4 | 3 | 3.07 | 4.43 | 3.93 | 2.64 | 3.65 |

| Number of members | |||||||||

| 1 to 10 members | 2.28 | 3.18 | 2.5 | 2.25 | 2.55 | 3.1 | 2.73 | 2.25 | 2.6 |

| More than 10 members | 3.03 | 4.04 | 3.5 | 2.78 | 2.69 | 3.38 | 2.96 | 2.51 | 3.11 |

| Years of activity | |||||||||

| 1 to 3 years | 2.66 | 4.03 | 3.34 | 2.48 | 2.13 | 2.52 | 2.14 | 1.95 | 2.66 |

| Over 3 years | 2.72 | 3.52 | 2.95 | 2.58 | 2.83 | 3.55 | 3.14 | 2.58 | 2.98 |

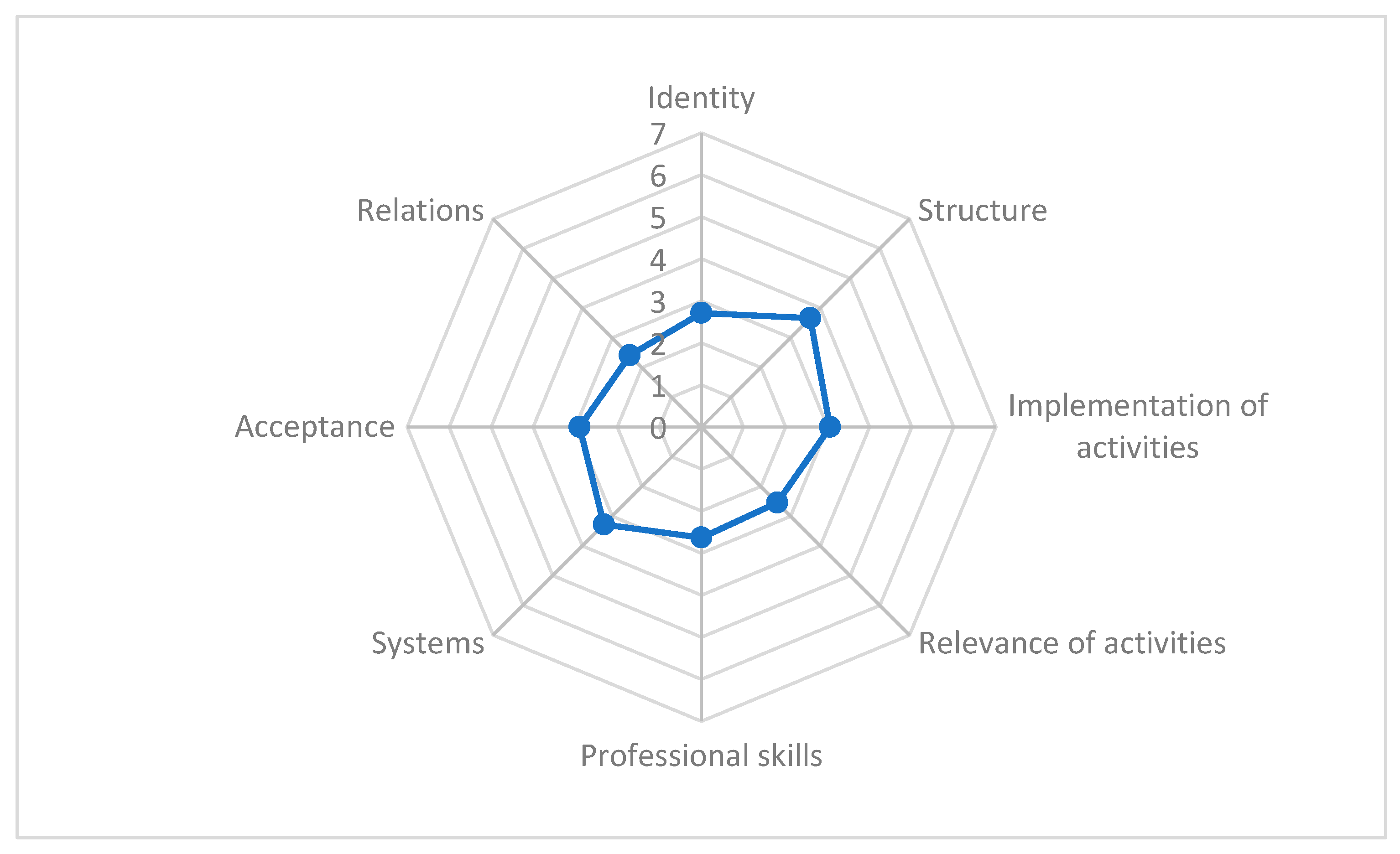

| General Average | 2.7 | 3.67 | 3.06 | 2.55 | 2.63 | 3.26 | 2.86 | 2.4 | 2.89 |

| Classification criteria | Score out of 100 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 19.88 | |

| Male | 33.54 | |

| Mixed | 27.25 | |

| Type of actor | ||

| Producer | 19.4 | |

| Marketer | 29.99 | |

| Consumer | 29.54 | |

| Academy | 35.95 | |

| Local government | 26.53 | |

| Service provider | 36.88 | |

| Agricultural suppliers | 33.19 | |

| Zone | ||

| Left bank of the Mantaro river | 23.67 | |

| Right bank of the Mantaro river | 24.75 | |

| Yacus valley | 23.11 | |

| Yanamarca valley | 20.9 | |

| All | 41.81 | |

| Number of members | ||

| 1 to 10 members | 26.12 | |

| More than 10 members | 26.30 | |

| Years of activity | ||

| 1 to 3 years | 22.52 | |

| Over 3 years | 27.68 | |

| General Average | 26.22 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and technical mastery of guinea pig production Proactive, persevering, dynamic actors with a tendency towards the community Some actors integrate LAG and practice governance Some actors were trained and are implementing the CFS-RAI Principles Interest of various actors in the development of the value chain |

Difficulty managing risk Vicarious learning from actors not addressed in training events Little prominence of the actors in the projects Predominantly informal marketing channels for guinea pigs Unsustainable resource management Presence of actors with weak organization and governance |

|

| Opportunities | Threats | |

| Demand for guinea pig meat grows Development of other guinea pig meat products Development of other marketing channels Integration of actors in an organization |

Social conflicts in Jauja Political instability Economic instability Drought due to climate change |

| Keeping Strengths | Combating Weaknesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Develop technical training in guinea pig production Generate environments and support that encourage a positive attitude Integrate the actors of the guinea pig value chain into the LAG Expand the implementation of CFS-RAI Principles to the entire chain Plan and develop the guinea pig value chain |

Risk management training Implement vicarious learning methodologies in projects Apply the bottom-up approach to projects Develop formal guinea pig marketing channels Train in sustainable resource management Strengthen organizations and promote governance |

|

| Exploiting Opportunities | Facing Threats | |

| Design strategies to satisfy the demand for guinea pig meat Research and innovate on new guinea pig meat products Encourage the development of other marketing channels Create an organization with the actors of the value chain |

Promote governance and transparency Improve resilience Diversify productive activities Implement efficient water use techniques |

| Element | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Develop project management competencies in technical teams of the actors that make up the Jauja guinea pig value chain. | |

| Objective group | Professionals in practice and in training, members of actors in the guinea pig value chain and committed to the development of the chain and its territory. | |

| Competencies to develop | The bases for individual competence in project management have been taken [33], with 28 competence elements distributed in three areas (Table 3). These competencies confer self-control, interpersonal connection, technical mastery and management of the environment to successfully conduct projects. | |

| Project orientation | The IPMA competencies are applied to a wide range of projects [33]; in this case they will be oriented to projects in the guinea pig value chain framed in the sustainable rural development of Jauja. | |

| Level to reach | Pass the performance evaluation with the level achieved or reach level D of the IPMA certification standard to be recognized as a project management technician [33]. | |

| Resources | The facilities of the RDC El Mantaro – UNMSM as promoter of this process, the collaboration of its research teachers and actors interested in the training process. | |

| Methodology | Employ the LEADER [23] and WWP [62] approaches, as well as the approaches recommended by IPMA: self-development, peer-supported development, education and training, coaching and mentoring, simulation and games [33]. Likewise, apply problem-based learning, project-based learning, social learning and learning by doing. | |

| Activity plan | Definition of the entry and exit profile. Preparation of the curricular plan. Call, evaluation and admission of participants. Training in conceptualization of IPMA competencies for project management. Basic-level training. Allows the basic mastery of competencies to face low-complexity situations. Example: personal and domestic projects. Intermediate-level training. This leads to the mastery of competencies to solve situations of medium complexity. Example: entrepreneurship and productive projects. Advanced-level programme. Trains in mastering competencies to resolve highly complex situations. Example: investment and development projects. Performance evaluation. Certification. |

| Element | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To strengthen institutional capacities for project management in actors of the guinea pig value chain in Jauja, with the aim of promoting the development of projects that contribute to the sustainable development of the Jauja territory. | |

| Components and activities | C1. Consolidate the organizations involved in the Jauja guinea pig value chain. A1. Review and adjust the structure and functions of the organization. A2. Prepare or update the strategic plan. C2. Improve the planning and management of activities to achieve results consistent with institutional objectives. A3. Evaluate and improve the activity planning and implementation process. A4. Carry out evaluation and monitoring of results. C3. Develop competencies in human capital for optimal resource management. A5. Develop competencies for efficient resource and project management. A6. Generate conducive environments for the development of projects. C4. Improve the organization's links with other actors in the territory. A7. Promote the dissemination of the activities of the organizations in the territory. A8. Evaluate and rethink the organization's contributions to the sustainable development of the territory. |

|

| Participants | Members, managers and representatives of the actors in the guinea pig value chain, representatives of other Jauja actors. | |

| Methodology | The WWP model [62], SWOT analysis and the LEADER approach [23] will be applied. | |

| Strategy | In the process of strengthening institutional capacities, the development of project management competencies is essential, since we consider it very important that a management team is responsible for leading the planning and management of institutional development as a first step, and then continue with the project work in a synergistic manner between actors that make up the value chain and between value chains to contribute to the development of the territory. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).