Submitted:

07 October 2023

Posted:

10 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3. Results

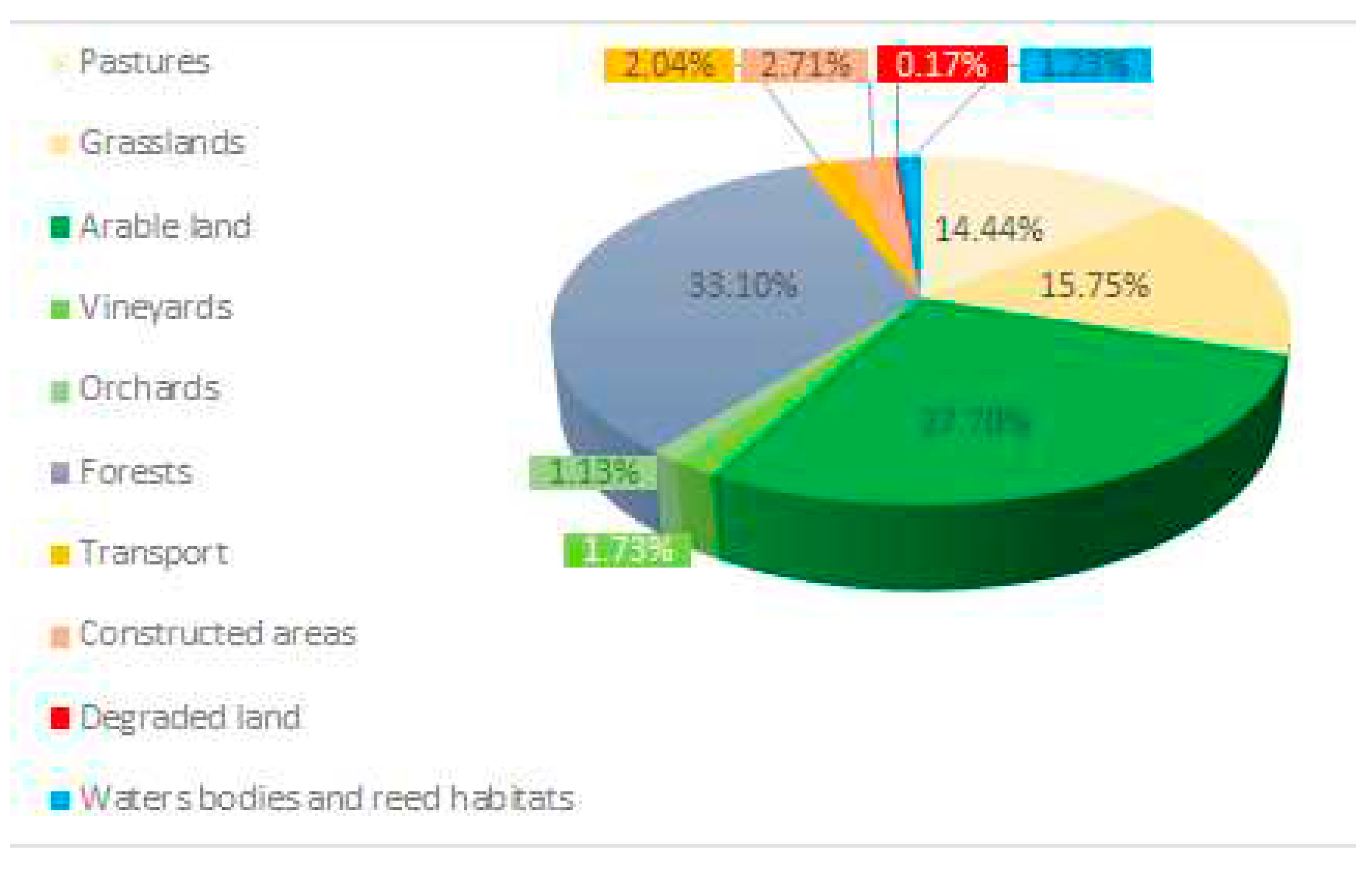

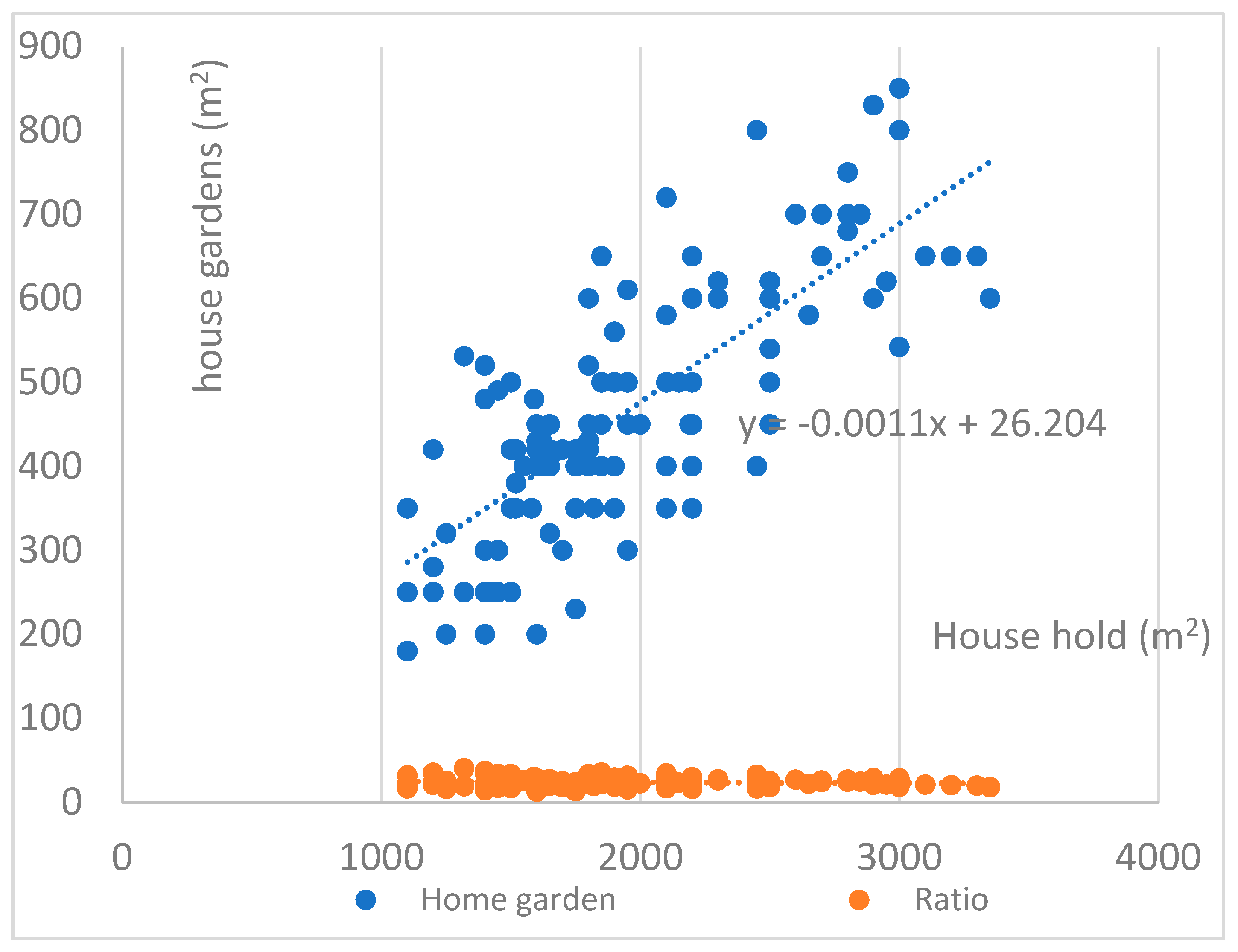

3.1. Traditional land use of Saxon-origin households

- -

- traditional Saxon properties where land use was preserved for more than 100 years;

- -

- slightly modified traditional Saxon properties where land use inside the household has slightly changed over the last 100 years, but where the main characteristics of land use, such as the ratio between the property area coverage and garden area, have been retained, and

- -

- profoundly modified properties where no traditional land use can be observed.

3.1.1. Traditional Saxon properties

3.1.2. Slightly modified traditional Saxon properties

3.1.3. Profoundly modified properties

3.2. Traditional and local knowledge related to home-gardening

3.3. PGRFA listing for their heritage value

3.4. Traditional home-gardens recongition for their heritage value at local level

4. Discussion

4.1. Traditional land use of Saxon-origin households

- -

- general land use inside households is similar;

- -

- traditional home-gardens, orchards, vineyards and grasslands are mostly located inside the urban area;

- -

- the intimate contact of households and gardens with forests and pastures or meadows is ensuring the wild-life long-term contact with agro-ecosystems and further support their status of hotspot of biodiversity conservation.

- Commission Directive 2008/62/EC of 20 June 2008 providing for certain derogations for acceptance of agricultural landraces and varieties which are naturally adapted to the local and regional conditions and threatened by genetic erosion and for marketing of seed and seed potatoes of those landraces and varieties; and

- Commission Directive 2009/145/EC of 26 November 2009 providing for certain derogations, for acceptance of vegetable landraces and varieties which have been traditionally grown in particular localities and regions and are threatened by genetic erosion and of vegetable varieties with no intrinsic value for commercial crop production but developed for growing under particular conditions and for marketing of seed of those landraces and varieties.

- The list of local populations cultivated for more than 100 years

- The list of ancient animal breeds

- The list of families owning local varieties with heritage value

- The list of traditional home-gardens

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Convention on Biological Diversity, Text of the Convention, https://www.cbd.int/convention/text/. (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, https://www.fao.org/planttreaty/overview/en/. (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, https://upovlex.upov.int/en/convention. (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Zeven, A.C. Landraces: a review of definitions and classifications. Euphytica, 1998, 104, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, F. Western science and traditional knowledge: Despite their variations, different forms of knowledge can learn from each other. EMBO reports 2006, 7, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S. Reflections on the Traditional Knowledge Debate. Cardozo J. Int'l & Comp. L. 2003, 11, 497. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, K. Problems of defining and validating traditional knowledge: A historical approach. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren DM (1989) Linking scientific Indigenous agricultural systems In, J.L. Compton (Ed.), The transformation of international agricultural research and development (pp. 153-170). Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder and London.

- Coombe, R.J. Intellectual Property, Human Rights & (and) Sovereignty: New Dilemmas in International Law Posed by Recognition of Indigenous Knowledge and the Conservation of Biodiversity. Ind. J. Global Legal Stud. 1998, 6, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, F.; Hardison, P.D. Traditional knowledge of indigenous and local communities: international debate and policy initiatives. Ecological applications 2000, 10, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olick, J.K.; Robbins, J. Social memory studies: From “collective memory” to the historical sociology of mnemonic practices. Annual Review of sociology 1998, 24, 105–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boym, S. Nostalgia and its discontents. The Hedgehog Review 2007, 9, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kammen, M. (2011). Mystic chords of memory: The transformation of tradition in American culture. Vintage.

- Gupta, S.M.; Arora, S.; Mirza, N.; Pande, A.; Lata, C.; Puranik, S.; Kumar, A. Finger millet: a “certain” crop for an “uncertain” future and a solution to food insecurity and hidden hunger under stressful environments. Frontiers in plant science 2017, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Hebinck, P.; Mathijs, E. Re-building food systems: embedding assemblages, infrastructures and reflexive governance for food systems transformations in Europe. Food Security 2018, 10, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D. I., Brown, A. H., Cuong, P. H., Collado-Panduro, L., Latournerie-Moreno, L., Gyawali, S., ... Hodgkin, T. A global perspective of the richness and evenness of traditional crop-variety diversity maintained by farming communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 5326–5331. [CrossRef]

- Padulosi, S., Bergamini, N.; & Lawrence, T. (2012). On-farm conservation of neglected and underutilized species: status, trends and novel approaches to cope with climate change: Proceedings of an International Conference, Frankfurt, 14-16 June, 2011.

- Gruberg, H.; Meldrum, G.; Padulosi, S.; Rojas, W.; Pinto, M.; & Crane, T. (2013). Towards a better understanding of custodian farmers and their roles: insights from a case study in Cachilaya, Bolivia. Bioversity International, Rome and Fundación PROINPA, La Paz.

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Aggarwal, P.K.; Ainslie, A.; Angelone, C.; Campbell, B.M.; Challinor, A.J.; Wollenberg, E. Options for support to agriculture and food security under climate change. Environmental Science & Policy 2012, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, A.W.; Engels, J.M. Plant biodiversity and genetic resources matter! . Plants 2020, 9, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, Y.; Poudel, R.C.; Shrestha, K.K.; Rajbhandary, S.; Tiwari, N.N.; Shrestha, U.B.; Asselin, H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2012, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plieninger, T.; Höchtl, F.; Spek, T. Traditional land-use and nature conservation in European rural landscapes. Environmental science & policy 2006, 9, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles, D. The Gabbra: Traditional social factors in aspects of land-use management. Nomadic Peoples, 1992, 41-52.

- Vos, W.; Meekes, H. Trends in European cultural landscape development: perspectives for a sustainable future. Landscape and urban planning 1999, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, D.W. Tradition, territory, and terroir in French viniculture: Cassis, France, and Appellation Contrôlée. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 2004, 94, 848–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manenti, R. Dry stone walls favour biodiversity: a case-study from the Appennines. Biodiversity and conservation 2014, 23, 1879–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Huang, X.Q.; Quenum FJ, B.; Chebotar, S.; Röder, M.S.; Börner, A. Genetic diversity in cultivated plants—loss or stability? . Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2004, 108, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Sakai, S.; Takahashi, T. Factors maintaining species diversity in satoyama, a traditional agricultural landscape of Japan. Biological Conservation 2009, 142, 1930–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, M.C.; Manfroi, E.; Wei, F.J.; Wu, H.P.; Lasserre, E.; Llauro, C.; Debladis, E.; Akakpo, R.; Hsing, Y.I.; Panaud, O. Retrotranspositional landscape of Asian rice revealed by 3000 genomes. Nature communications 2019, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightfoot, K.G.; Cuthrell, R.Q.; Striplen, C.J.; Hylkema, M.G. Rethinking the study of landscape management practices among hunter-gatherers in North America. American Antiquity 2013, 78, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.M.; Rivera, J.A.; Miller, A.; Piccarello, M. Ecosystem services of traditional irrigation systems in northern New Mexico, USA. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 2014, 10, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, C.T. Spatial patterning in the dooryard gardens of Puerto Rico. Geographical Review 1973, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, M. S.; Ladio, A.; Peroni, N. Landscapes with Araucaria in South America: evidence for a cultural dimension. Ecology and Society 2014, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Samberg, L.H.; Fishman, L.; Allendorf, F.W. Population genetic structure in a social landscape: barley in a traditional Ethiopian agricultural system. Evolutionary Applications 2013, 6, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, A.L.; Falkenberg, T.; Rautenbach, C.; Moshabela, M.; Shezi, B.; Van Ellewee, S.; Street, R. Legislative landscape for traditional health practitioners in Southern African development community countries: a scoping review. BMJ open 2020, 10, e029958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Traditional uses of wild and tended plants in maintaining ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes of the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2022, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Komar, O.; Chazdon, R.; Ferguson, B.G.; Finegan, B.; Griffith, D.M.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Morales, H.; Nigh, R.; Soto-Pinto, L.; van Breugel, M.; Wishnie, M. Integrating agricultural landscapes with biodiversity conservation in the Mesoamerican hotspot. Conservation biology 2008, 22, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention , (accessed on 30 September 2023). (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Casas, J. J.; Bonachela, S.; Moyano, F. J.; Fenoy, E.; & Hernández, J. (2015). Agricultural practices in the mediterranean: A case study in Southern Spain. In The Mediterranean Diet (pp. 23-36). Academic Press.

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; García-Arca, D.; López-Felices, B. Identification of opportunities for applying the circular economy to intensive agriculture in Almería (South-East Spain). Agronomy 2020, 10, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akparov, Z.; Asgerov, A.; Mammadov, A. Agrodiversity in Azerbaijan. Biodiversity, Conservation and Sustainability in Asia: Volume 1: Prospects and Challenges in West Asia and Caucasus. 2021, 479-499.

- Harrop, S.R. Traditional agricultural landscapes as protected areas in international law and policy. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2007, 121, 296–307. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Singh, G.S. Traditional agriculture: a climate-smart approach for sustainable food production. Energy, Ecology and Environment 2017, 2, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, J.M.; Lasanta, T.; Nadal-Romero, E.; Lana-Renault, N.; Álvarez-Farizo, B. Rewilding and restoring cultural landscapes in Mediterranean mountains: Opportunities and challenges. Land use policy 2020, 99, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermeer, J.; Perfecto, I. Complex traditions: Intersecting theoretical frameworks in agroecological research. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2013, 37, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A. How traditional agro-ecosystems can contribute to conserving biodiversity Jeffrey A. McNeely. Conserving biodiversity outside protected areas: The role of traditional agro-ecosystems 1995, 20, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, G.; Eyzaguirre, P.; Negri, V. Home-gardens: neglected hotspots of agro-biodiversity and cultural diversity. Biodiversity and conservation 2010, 19, 3635–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.K.; Upadhyay, M.P.; Gauchan, D.; Sthapit, B.R.; Joshi, K.D. Red listing of agricultural crop species, varieties and landraces. Nepal Agric. Res. J 2004, 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, K.; Khoshbakht, K. Towards a ‘red list’for crop plant species. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2005, 52, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegel, R. (2012). Red list for crops-a tool for monitoring genetic erosion, supporting re-introduction into cultivation and guiding conservation efforts. In On farm conservation of neglected and underutilized species: status, trends and novel approaches to cope with climate change. Proceedings of an international conference, Frankfurt, Germany, 14-16 June, 2011 (pp. 137-142). Bioversity International.

- Antofie, M.M. The Red List of Crop Varieties for Romania-Lista Roşie a varietăţilor plantelor de cultură din România. Publishing House Lucian Blaga Univresity from Sibiu, 2011, 81.

- Ebert, A.W.; Engels, J.M.; Schafleitner, R.; Hintum, T.V.; Mwila, G. Critical Review of the Increasing Complexity of Access and Benefit-Sharing Policies of Genetic Resources for Genebank Curators and Plant Breeders–A Public and Private Sector Perspective. Plants 2023, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Brush, S.; Costich, D.E.; Curry, H.A.; De Haan, S.; Engels, J.M.; Thormann, I. Crop genetic erosion: understanding and responding to loss of crop diversity. New Phytologist 2022, 233, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westengen, O. T.; Skarbø, K.; Mulesa, T. H.; Berg, T. Access to genes: Linkages between genebanks and farmers’ seed systems. Food Security 2018, 10, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulosi, S.; Bala Ravi, P.; Rojas, W.; Sthapit, S. R.; Subedi, A.; Dulloo, M. E. ;... & Warthmann, N. (2012). Red lists for cultivated species: why we need it and suggestions for the way forward.

- Schmitt, T.; Rákosy, L. Changes of traditional agrarian landscapes and their conservation implications: a case study of butterflies in Romania. Diversity and distributions 2007, 13, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulcak, F.; Newig, J.; Milcu, A.I.; Hartel, T.; Fischer, J. Integrating rural development and biodiversity conservation in Central Romania. Environmental Conservation 2013, 40, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolovan, I.; Bolovan, S.P. From tradition to modernization. Church and the Transylvanian Romanian Family in the Modern Era. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 2010, 7, 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, N.; Bartha, S.; Boris, G.; Balogh, L. Traditional uses of medicinal plants for respiratory diseases in Transylvania. Natural Product Communications 2011, 6, 1934578X1100601012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, T.; Dorresteijn, I.; Klein, C.; Máthé, O.; Moga, C. I.; Öllerer, K.; ... & Fischer, J. Wood-pastures in a traditional rural region of Eastern Europe: Characteristics, management and status. Biological Conservation 2013, 166, 267–275.

- Papp, N.; Bencsik, T.; Stranczinger, S.; Czégényi, D. Survey of traditional beliefs in the Hungarian Csángó and Székely ethnomedicine in Transylvania, Romania. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2014, 24, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antofie, M.M. Defining indicators for investigating traditional home-gardens in Romania. Scientific Papers Series-Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 2020, 20, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Antofie, M.M.; Sava, C.S. Indicators for investigating traditional home-gardens in Romania-crops diversity in Mosna commune, Sibiu county. Scientific Papers Series-Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 2020, 20, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Antofie, M.M.; Sava, C.S. Indicators for investigating traditional home-gardens in Romania-vineyrads, fruit trees and cultivated shrubs diversity in Moşna commune, Sibiu county. Scientific Papers Series-Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 2020, 20, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

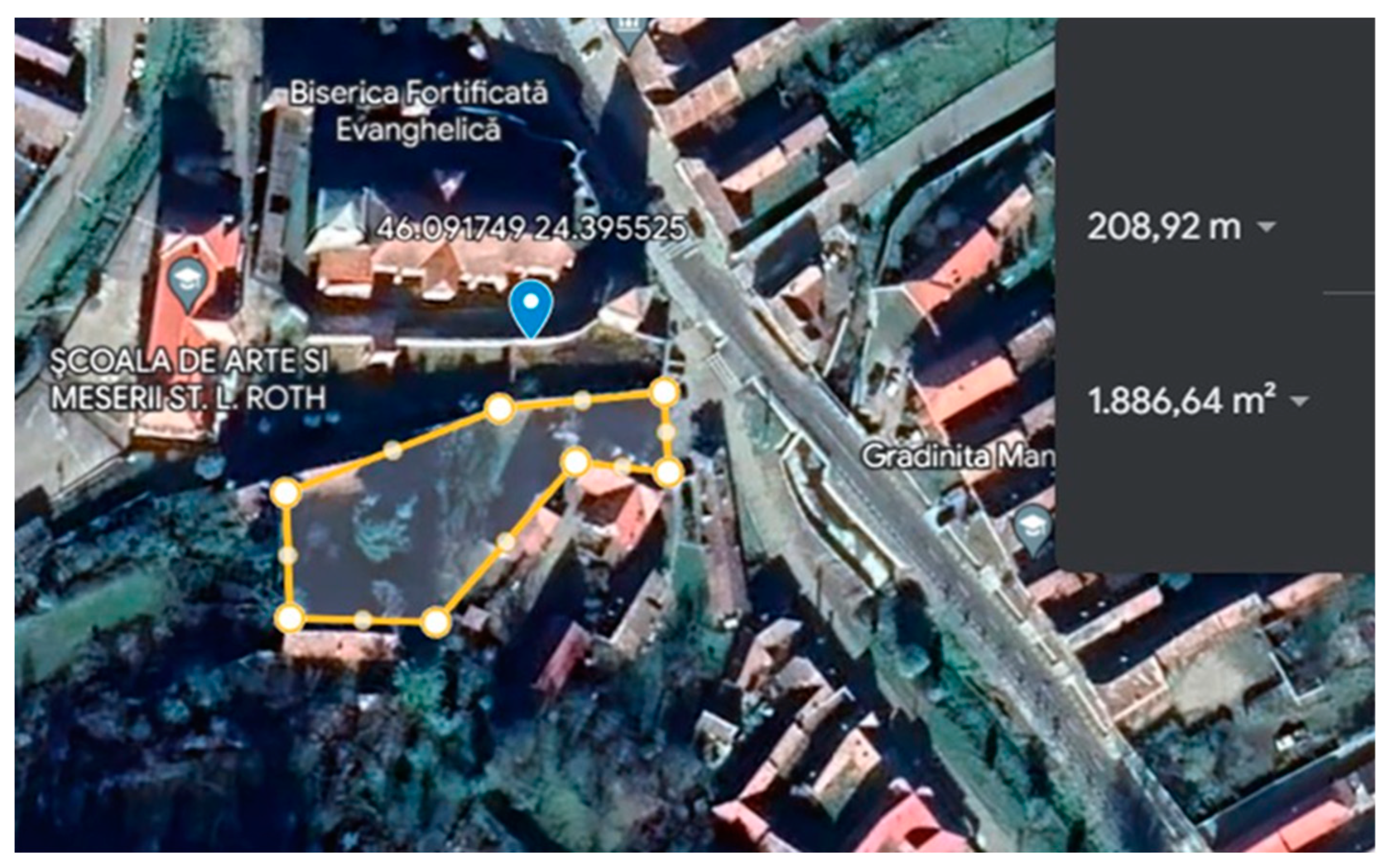

- Google Earth project, https://earth.google.com/web., (accessed on 30 September 2023). (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Antofie, M. M.; Sava, C.; Máthé, E. (2019). Chestionar privind evaluarea în teren a resurselor genetice pentru alimentaţie şi agricultură. Editura Universită.ţii" Lucian Blaga".

- Qingwen, M. (2016). Promoting rural revitalization through the conservation of Agricultural Heritage Systems. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 7.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI), https://www.ipni.org/, (accessed on 30 September 2023). (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Anghel, R.; Berevoescu, I.; Haşdeu, I.; & Mihăilescu, V. 1999, World Bank coordinator: Thomas Blinkhorn Research coordinator: Dumitru Sandu Research team. Reconstructing community space – social assessment of Moșna and Viscri – two former saxon villages in Romania, 75 p.

- Şotropa, I.; Şotropa, M. (2001). Mosna: monografie. Publishing House Etape Sibiu, ISBN 973-9090-86-9.

- Raport de mediu, 2017, http://apmsb.anpm.ro/documents/27013/2414179/PUG+Mosna+-raport+de+mediu.pdf/2b71f508-efae-4882-a3ae-ce735c76cb8f. 4882.

- Steffen, W.; Crutzen, P.J.; McNeill, J.R. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature. Ambio-Journal of Human Environment Research and Management 2007, 36, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhacham, E.; Ben-Uri, L.; Grozovski, J.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Milo, R. Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature 2020, 588, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.J. Understanding plastics pollution: The role of economic development and technological research. Environmental pollution 2019, 249, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruckelshaus, M.H.; Jackson, S.T.; Mooney, H.A.; Jacobs, K.L.; Kassam KA, S.; Arroyo, M.T.; Báldi, A.; Bartuska, A.M.; Boyd, J.; Joppa, L.N.; Kovács-Hostyánszki, A.; Parsons, J.P.; Scholes, R.J.; Shogren, J.F.; Ouyang, Z. The IPBES global assessment: pathways to action. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2020, 35, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Raimi, M. O.; Iyingiala, A. A.; Sawyerr, O. H.; Saliu, A. O.; Ebuete, A. W.; Emberru, R. E.; Sanchez, N.D.; Osungbemiro, W. B. (2022). Leaving no one behind: impact of soil pollution on biodiversity in the global south: a global call for action. In Biodiversity in Africa: Potentials, Threats and Conservation (pp. 205-237). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Gallegos, D.; Eivers, A.; Sondergeld, P.; Pattinson, C. Food insecurity and child development: A state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and public health 2021, 18, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, C.L.; Ureksoy, H. Water insecurity in a syndemic context: Understanding the psycho-emotional stress of water insecurity in Lesotho, Africa. Social science & medicine 2017, 179, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard, L.; Caron, P.; Campbell, B.; Lipper, L.; Mainka, S.; Rabbinge, R.; Pulleman, M. Reconciling biodiversity conservation and food security: scientific challenges for a new agriculture. Current opinion in Environmental sustainability 2010, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, M.J.; LaValle, L.A. Food security and biodiversity: can we have both? An agroecological analysis. Agriculture and human values 2011, 28, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, M.; Kelly, M. Exploring the links between desertification and climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 1993, 35, 4–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikis, J.; Baležentis, T. Agricultural sustainability assessment framework integrating sustainable development goals and interlinked priorities of environmental, climate and agriculture policies. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Skoff, J.B.; Cavender, N. The benefits of trees for livable and sustainable communities. Plants, People, Planet 2019, 1, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. Community, connection and conservation: Intangible cultural values in Natural Heritage—the case of Shirakami-sanchi World Heritage Area. International journal of heritage studies 2006, 12, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeroyd, J.R.; Page, J.N. Conservation of High Nature Value (HNV) grassland in a farmed landscape in Transylvania, Romania. Contributii Botanice 2011, 46, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Opincariu, D.S.; Voinea, A.E. Cultural identity in Saxon rural space of Transylvania. Acta Technica Napocensis: Civil Engineering & Architecture 2015, 4, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Anghel, R.; Berevoescu, I.; Haşdeu, I.; & Mihăilescu, V. 1999, World Bank coordinator: Thomas Blinkhorn Research coordinator: Dumitru Sandu Research team. Reconstructing community space – social assessment of Moșna and Viscri – two former saxon villages in Romania, 75 p.

- Sutcliffe, L.; Akeroyd, J.; Page, N.; Popa, R. Combining approaches to support high nature value farmland in southern Transylvania, Romania. Hacquetia, 2015, 14.

- NATURA 2000 - Standard Data Form, https://natura2000.eea.europa.eu/Natura2000/SDF.aspx?site=ROSCI0304, (accessed in 14 September 2023). 14 September.

- Culbert, P.D.; Dorresteijn, I.; Loos, J.; Clayton, M.K.; Fischer, J.; Kuemmerle, T. Legacy effects of past land use on current biodiversity in a low-intensity farming landscape in Transylvania (Romania). Landscape ecology 2017, 32, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.; Hackett, J.; DeRoy, S. Mapping the digital terrain: towards indigenous geographic information and spatial data quality indicators for indigenous knowledge and traditional land-use data collection. The Cartographic Journal 2016, 53, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Guo, S.; Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Cao, S. The impact of rural laborer migration and household structure on household land use arrangements in mountainous areas of Sichuan Province, China. Habitat International 2017, 70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z.; Van der Molen, P.; Bennett, R.M.; Kuusaana, E.D. Land consolidation, customary lands, and Ghana's Northern Savannah Ecological Zone: An evaluation of the possibilities and pitfalls. Land use policy 2016, 54, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.K.; Walsh, S.J.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Frizzelle, B.G.; Erlien, C.M.; Baquero, F. Farm-level models of spatial patterns of land use and land cover dynamics in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2004, 101, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gulinck, H.; Múgica, M.; de Lucio, J.V.; Atauri, J.A. A framework for comparative landscape analysis and evaluation based on land cover data, with an application in the Madrid region (Spain). Landscape and urban planning 2001, 55, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamesouti, M.; Detsis, V.; Kounalaki, A.; Vasiliou, P.; Salvati, L.; Kosmas, C. Land-use and land degradation processes affecting soil resources: Evidence from a traditional Mediterranean cropland (Greece). Catena 2015, 132, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overwalle, G. Protecting and sharing biodiversity and traditional knowledge: Holder and user tools. Ecological Economics 2005, 53, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poponi, S.; Arcese, G.; Mosconi, E.M.; Pacchera, F.; Martucci, O.; Elmo, G.C. Multi-actor governance for a circular economy in the agri-food sector: bio-districts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, C.; Swain, K.C. Land suitability evaluation criteria for agricultural crop selection: A review. Agricultural reviews 2016, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna-Firme, R. (2012). Nature conservation, ethnic identity, and poverty: the case of a quilombola community in São Paulo, Brazil (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University).

- Silver Coley, L.; Lindemann, E.; Wagner, S.M. Tangible and intangible resource inequity in customer-supplier relationships. Journal of business & industrial marketing 2012, 27, 611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Kothari, A. Traditional agricultural landscapes and community conserved areas: an overview. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2011, 22, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheed, S.; Shooshtarian, S. The role of cultural heritage in promoting urban sustainability: A brief review. Land 2022, 11, 1508, Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, S.; Wynberg, R.; Rourke, M.; Humphries, F.; Muller, M.R.; Lawson, C. Rethink the expansion of access and benefit sharing. Science 2020, 367, 1200–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruta, C.; Campanelli, A.; De Mastro, G.; Blando, F. In vitro propagation by axillary shoot culture and somatic embryogenesis of Daucus carota l. subsp. sativus,‘Polignano’landrace, for biodiversity conservation purposes. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma, S.; Karthic, R.; Kalpana, S.; Backiyarani, S.; Kumaravel, M. , Saranya, S.,... & Durai, P. (2023). An efficient embryogenic cell suspension culture system through secondary somatic embryogenesis and regeneration of true-to-type plants in banana cv. Sabri (silk subgroup AAB). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 1–10.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements,opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

| Crt. no | Scientific name (vernacular Romanian name) |

Household no. in Moșna localities |

|---|---|---|

| Crops as landraces | ||

| 1. | Allium sativum L. (usturoi) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (19, 254*, 268, 418) Nemșa (51,111) |

| 2. | Anethum graveolens L. (mărar) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (268, 418, 420), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 3. | Apium graveolens L. (țelină) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (254*, 268, 417, 418), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 4. | Armoracia rusticana G.Gaertn., B.Mey. & Scherb. (hrean) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (420), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 5. | Artemisia dracunculus L. (tarhon) | Moșna (417) |

| 6. | Brassica oleracea var. capitata L. (varză de Moșna) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (1/C, 254*, 268, 418, 402, 461),Nemșa (51,111) |

| 7. | Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss (pătrunjel) | Moșna (268, 417, 420) |

| 8. | Phaseolus vulgaris L. var ‘nana’ (fasole oloagă) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (418), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 9. | Rheum rhabarbarum L. (rubarbăr) | Evangelic Church Garden Moșna 530 |

| 10. | Satureja hortensis L. Cimbru | Moșna (254*, 206, 420) |

| 11. | Zea mays L., (porumb pe 8 rânduri) | Moșna (12) |

| 12. | Zea mays L. (porumb roșu de Moșna) | Moșna (543) |

| Fruit trees, shrubs and vineyards | ||

| 13. | Cydonia oblonga Mill. (gutui) | Moșna (19, 206) |

| 14. | Prunus armeniaca L. (cais) | Moșna (19, 268) |

| 15. | Prunus domestica L. (prun) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (268), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 16. | Prunus persica (L.) Batsch (piersic) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (254*, 268), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 17. | Rubus idaeus L. (zmeură săsească – local[) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (19, 417, 530), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 18. | Vitis vinifera L. ‘Perla negra’ (viță Perlă Neagră) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (254*, 417) |

| 19. | Vitis vinifera L. ‘Risling’ (viță Risling) | Moșna (254*), Nemșa (51) |

| 20. | Vitis vinifera L. Hybrid (viță Nova) | Moșna (417) |

| Crt. No | Scientific name (vernacular Romanian name) |

Household no. in Moșna localities |

|---|---|---|

| Crops as landraces | ||

| 1 | Allium cepa L., (ceapă locală) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (254*, 268, 417, 418, 420), Nemșa (51,111). |

| 2. | Cucumis sativus L. (crastraveți) | Moșna (254*, 268, 417, 418, 420), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 3. | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne (bostan plăcintar) | Evangelic Church Garden, Moșna (530). |

| 4. | Lactuca sativa L. (salată verde) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (19, 254*, 268, 417, 418, 420), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 5. | Mentha L. sp. (mentă) | Moșna (420) |

| 6. | Phaseolus vulgaris L. (fasole de haraci) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (19, 418, 417, 420), Nemșa (51,111) |

| 7. | Solanum lycopersicum L. (roșii) | Alma Vii (182), Moșna (19, 206, 254*, 268, 420, 417, 418), Nemșa (51,111), Evangelic Church Garden |

| 8. | Solanum tuberosum L. (cartofi albi) | Moșna (417) |

| 9. | Spinacia oleracea L. (spanac) | Moșna (417) |

| 10. | Zea mays L., Turda 200 (Porumb Turda 200) | Moșna (254*) |

| Crt. no | Household no. in Moșna localities | Landraces and animal bred in home-gardens of heritage values |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Moșna 254* | Garlic, onion, tomatoes, Moșna cabbage, thyme, yellow maize with 8 rows cobs, celery. |

| 2. | Moșna 418 | Moșna cabbage, tomatoes, dwarf beans, thyme, celery. |

| 3. | Nemșa 111 | Onion, garlic, plum-trees, thyme, celery, Saxon raspberry. |

| 4. | Moșna 206 | Thyme, celery, horseradish. |

| 5. | Moșna 268 | Salad, tomatoes, Moșna cabbage, dill, cucumbers, Bazna pig. |

| 6. | Moșna 12 | yellow maize with 8 rows cobs, thyme, celery. |

| 7. | Alma Vii 182 | Garlic, onion, Moșna cabbage, eggplants, Saxon raspberry. |

| 8. | Moșna 420 | Tomatoes, thyme, beans, parsley, dill. |

| 9. | Moșna 417 | Vine Nova, beans, potatoes, Saxon raspberry, thyme, celery |

| 10. | Moșna 19 | Saxon raspberry, quince, apricot, thyme, celery. |

| 11. | Moșna 530 | Pumpkin for pies, tomatoes, Saxon raspberry, rhubarb, thyme, celery. |

| 12. | Nemșa 51 | Garlic, onion, Saxon raspberry, plum-trees, thyme, celery. |

| 13. | Moșna 461 | Moșna cabbage, thyme, celery. |

| 14. | Moșna 1/C | Moșna cabbage producer for selling, thyme, celery. |

| 15. | Moșna 402 | Moșna cabbage, thyme, celery. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).