1. Introduction

Workplace incivility (WPI) describes low-intensity workplace deviant acts such as rudeness, condescending attitudes, and ignoring colleagues (Cortina et al., 2022). WPI can be ambiguous and are generally not outright malicious onslaughts like sexual harassment (Yao et al., 2022). WPI can be expressed as high-intensity workplace transgressions (e.g., physical intimidation) that aggravate debilitating mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, emotional exhaustion, lowered well-being (Schilpzand et al. 2016) and negative consequences such as decreased job performance, lower productivity, work withdrawal behaviours and turnover intentions (Vasconcelos, 2020) for organisations (Agarwal et al., 2023). In a five-week study, greater stress was experienced by employees (n=130) of a security firm in New South Wales (Australia) during the days in which they reported greater levels of WPI (Beattie and Griffin, 2014). Depression and higher levels of anger and lowered self-esteem were associated with daily experiences of WPI in another ten-day longitudinal study of Swiss workers (n=164) from various professional backgrounds (Adiyaman and Meier, 2022). WPI was also associated with lowered subjective well-being, increased headaches, sleep disturbances and digestive problems in a cross-sectional study of nurses (n=290) in a south-eastern US state (Sherrod and Lewallen, 2021), and for teachers (n=341) in both Jammu (India) government and private colleges (Sood and Kour, 2023).

On the association between WPI and anxiety, a cross-sectional study involving postal workers (n=950) in Canada, Geldart et al. (2018) reported that WPI was positively associated with anxiety as well as depression, hostility and burnout, after controlling for demographic and work factors. Similarly, a six-month longitudinal study on Romanian workers found that employees with trait-anxiety reported higher bullying (Reknes et al., 2021). In China, junior nurses (n=903) across 29 provinces revealed that anxiety partially mediated WPI and job-burnout (Shi et al. 2018), whereas telecommunications employees (n=507) from six small to medium-sized enterprises companies in Pakistan, (De Clercq et al. 2020) showed that anxiety mediated WPI and depersonalised behaviour.

Cortina et al. (2017) found biological sex effects where females and younger workers were more prone to experience WPI compared to males and older workers. A significant negative medium-sized effect between WPI and age was found but not for gender (Han et al., 2021). In Singapore, a study (Lim and Lee 2011) involving employees (n=180) reported that men and younger workers experienced more WPI than women and older workers when considered together with the significant negative Spearman correlation between social anxiety and civility (Cheok et al., 2020), highlights the relevance in the workplace and society at large. In fact, the discrepancies between reports on gender effects were likely due to local differences in perspectives to ethnic groups and biological sexes (McCord et al, 2018), with a notable decrease in sex descriptions over the years.

Collectively, the association between workplace social stressors and both employee health as well as workplace attitude/behaviour were previously reported to be of medium effect size (r = -.30, p < .001) from a meta-analysis (Gerhardt et al., 2021) of 555 studies. Collectively, these data suggest that anxiety may play an indirect or mediating role between

WPI and mental well-being.

For the organization, WPI negatively affected job performance and innovation (Jiang et al., 2019), conversely increasing turnover intentions (Namin et al., 2022). In a more subtle manner, knowledge-hiding can occur (Arshad and Ismail, 2018). Work withdrawal in the form of cyberloafing or spending time on the internet for non-work purposes notably increased with increased WPI among civil servants (n=327) in Nigeria (Bernard and Joe-Akunne, 2019), with some employees spending precious time away from actual work crafting retaliatory responses to rude emails (McCarthy, 2016).

Negatively impacting work engagement that is defined as being immersed in work with vigour, dedication and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2006), decreased job satisfaction in Malaysian civil servants (Alia et al., 2022), Taiwanese hospitality staff (Wang and Chen, 2020) found both co-worker and customer incivility to lead to reduced work engagement and job performance. Among frontline hotel employees in the Midwest USA (Im and Cho, 2022), supervisor WPI was negatively correlated with employee engagement as well as self-efficacy, resulting in reduced service delivery.

Despite the vast literature on WPI, mediation analysis investigating WPI and work engagement are few. One study on working adults in the United States with depression and/or bipolar disorder (n=272) found WPI and work engagement to be mediated through suicidal ideation among employees (Follmer and Follmer, 2021). Interestingly, in China, job insecurity mediated WPI and work engagement (Guo et al., 2022) without significant direct effects from WPI on work engagement.

To further investigate the effect of WPI on social anxiety and work engagement, this study investigates the hypotheses that: 1) WPI will positively and significantly predict social anxiety, after controlling for covariates age and gender; 2) WPI will have an indirect negative impact on work engagement through social anxiety.

2. Results

2.1. Assumption Testing

Major regression assumptions (e.g., Tabachnick and Fidel, 2013; Pallant, 2020) were met in the present study. Firstly, the residuals were deemed to be independent as the data-points were not correlated with each other (Durbin-Watson statistic = 2.01, falling within the acceptable ranges of 1 and 3). Secondly, there was homoscedasticity in residuals as indicated by the elliptical scatter plot of the regression standardised predicted values against the regression standardised residuals. Thirdly, the errors were normally distributed: (1) The histogram of the errors appeared somewhat bimodal though approximately normal, i.e. not skewed; (2) The normal P-P plot of the residuals showed some deviation from the plot’s predicted straight line generally normal; and (3) Both the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests of the unstandardised residuals were not statistically significant (p=.200 and p=.235, respectively). Fourthly, there were linear relationships between the dependent variable (work engagement) and each of the continuous variables (WPI, social anxiety and age) from the scatter plots. Next, multicollinearity was not evident as zero-order correlation coefficients among the independent variables were below .70, VIF was under 5 and Tolerance above .20. Finally, there was no undue influence as Cook’s Distance for all data points was below 1.

2.2. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics are shown in

Table 1. The mean WPI score of 1.94

+ 0.88 was close to the WIS Likert score of 2 (i.e., seldom experience incivility at the workplace). Comparatively, 89% (all the mean scores of WPI are above 1) showing that most participants experienced some form of WPI (score above 1). This is similar to the 91% prevalence reported in Lim and Lee (2011). Thus, while there is a high prevalence of workplace incivility, the intensity is relatively low. The mean social anxiety score of 1.14

+ 0.98 was close to the SAD-6 Likert score of 1 in the SAD-6 (i.e., occasionally experienced social anxiety). When the SAD-6 was computed as a sum, 6.82

+ 5.9 out of 40, it was found relatively similar to the 10.8

+ 8.89 score reported for a community sample by Rice et al. (2021). The mean work engagement score of 3.14

+ 1.35 was close to the UEWS-9 score of 3 (i.e., “sometimes or a few times a month” felt total engagement with their work). Comparatively, this is one Likert scale point lower than that reported in Stefanidis and Strogilos (2021) finding that parents of children with special needs often felt engaged with their work, possibly given their supportive environment.

2.3. Correlational analysis

A significant, positive relationship was found between WPI and social anxiety (r=.55, p<.001) and between age and work engagement (r=.43, p<.001) whereas a significant, negative association was found between age and WPI (r=-.24, p=.01); WPI and work engagement (r=-.414, p<.001); social anxiety and work engagement (r=-.55, p<.001); and age and social anxiety (r=-.38, p<.001). Biological sex did not show significant associations with WPI, social anxiety, work engagement or age.

Generally, higher levels of WPI were associated with higher levels of social anxiety but lower levels of work engagement.

2.4. Hierarchical Regression

To measure the impact of WPI on social anxiety (after controlling for age and biological sex), the hierarchical regression found that WPI accounted for 20.3% of the variation in social anxiety (ΔR2 = .203, ΔF(F (1,108) =) = 33.67, p<.001) with a medium effect size (f2=.25).

Table 2 on the hierarchical regression of WPI affecting social anxiety and covariates (age and biological sex) on work engagement, had Model 1 comprising of the covariates age and gender that accounted for 18.90% of the variation in work engagement (ΔR2 = .19, ΔF(F (2,110) =) = 12.92, p<.001) with a medium effect size (f2=0.23). In Model 2, WPI was introduced after controlling for age and gender and contributed a further 12.6% of the variation on work engagement (ΔR2 = .13, ΔF(F (1,109) = 20.94, p<.001) with a medium effect size (f2 =.15). In Model 3, social anxiety was introduced, and after controlling for age, gender and WPI and contributed a further 6% of the variation (ΔR2 = .06, ΔF(F (4,108) = 10.63, p<.002). This final model accounted for about 38.2% of the variation in work engagement, (R2 = .38, ΔF(F (4,108) = 16.66, p<.001) with a large effect size (f2 =0.60). Social anxiety had the largest impact (β=-.31, p=.002) followed by age (β=.25, p=.003) and then WPI (β=-.23, p=.01) with biological sex showing p >0.05. Social anxiety weakened the contribution of WPI (β of WPI decreased from -.37 to -.23) suggesting a partial mediating effect (because WPI remained significant).

2.5. Mediation Analysis

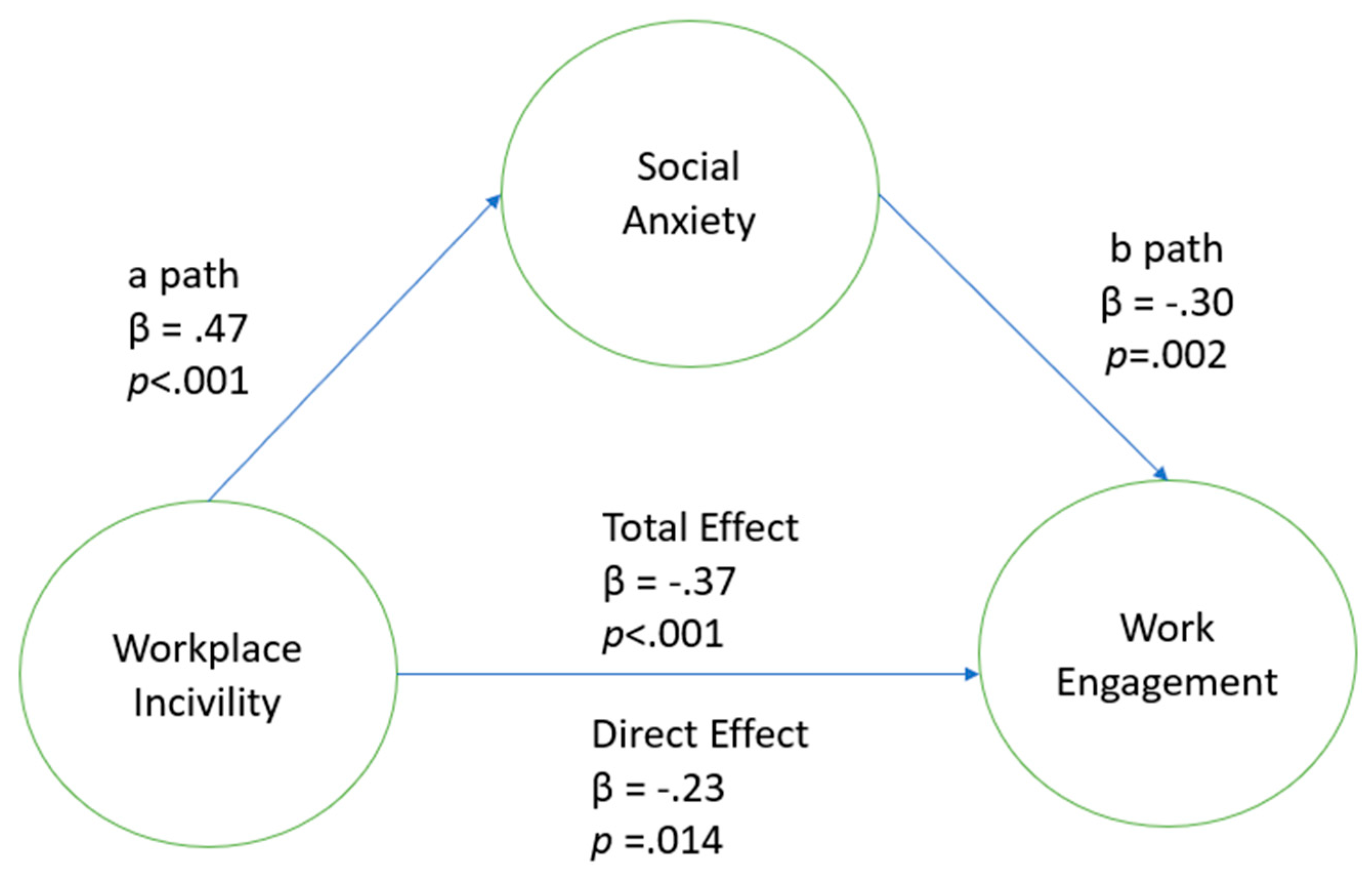

Mediation analysis was performed using Model 4 of Hayes ’ (2018) PROCESS macro (v.4.2) for SPSS reporting 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the indirect effect based on percentile bootstrapping with 5,000 samples. The results are presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 1.

Hypothesis 1 - WPI would positively and significantly predict social anxiety after controlling for covariates age and biological sex.

Upon controlling for covariates, age was found to be significantly negatively associated with social anxiety. Biological sex did not show significant associations. Controlling for both age and gender, WPI was significantly and positively associated with social anxiety (a path) with a medium effect size ( Δ(ΔR2 =.20). Thus, the first hypothesis of this study was accepted.

Hypothesis Testing 2 - WPI will have an indirect negative impact on work engagement through social anxiety.

WPI had a significant negative total effect on work engagement (c path) controlling for age and biological sex. Social anxiety was significantly negatively associated with work engagement (b path) after controlling for WPI, age and biological sex. Thus, the indirect effect of WPI on work engagement through social anxiety (ab path) was shown significantly negative. The direct effect of WPI on work engagement, controlling for social anxiety and covariates was also significantly negative (c’ path). Therefore, WPI has a negative effect on work engagement and this relationship can be explained through the hypothesized mediating effect of social anxiety. Specifically, social anxiety partially mediated between WPI and work engagement because the c’ path remained statistically significant. Thus, the second hypothesis of the study was also accepted.

Simple mediation model

Small, medium and large effect sizes (f2) were based on values of .02, .15 and .35, respectively (Cohen, 1988). Hayes PROCESS macro was used to estimate the mediation effect of social anxiety (Hayes, 2018).

3. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate if WPI could positively predict social anxiety and if it had an indirect negative impact on work engagement through social anxiety (partial or full mediation). The analysis supported accepting both hypotheses, given that WPI was positively associated with social anxiety after controlling for covariates and its negative impact on work engagement, partially mediated by social anxiety.

Upon controlling for covariates, WPI showed a medium effect in predicting social anxiety which was similar to the medium effect reported between workplace social stressors and employee health in a meta-analysis (Gerhardt et al., 2021). Employees who experienced higher levels of WPI also experienced greater levels of social anxiety. The findings here were also congruent with other studies also finding the negative impact of WPI on stress (Beattie and Griffin, 2014) depression (Adiyaman and Meier, 2022), lower subjective well-being (Sherrod and Lewallen, 2021), lower psychological well-being (Sood and Kour, 2023), rumination after work (Vahle-Hinz, 2019) and anxiety (Geldart et al., 2018).

Our findings here updated the literature on WPI and social anxiety given that the majority of studies to date utilized scales developed before 1985, and we further found social anxiety to be a mediating factor. While Lim and Lee (2011) did not find in their Singapore employees, a significant association between anxiety with either co-worker or supervisor initiated WPI, the study also utilized a different scale, capturing a different form of anxiety other than social anxiety. Nonetheless, the related congruency with another finding by Cheok et al. (2020) of an association between social anxiety and civility may reflect changing perspectives or work environments in Singapore workplaces in the early 2010s and the 2020s.

The accepted second hypothesis that the negative impact of WPI on work engagement was partially mediated through social anxiety (partial mediation) after controlling for age and gender, agreed with the meta-analysis study reporting a medium effect between social stressors and workplace attitudes/behaviour (Gerhardt et al., 2021). Employees who encountered more WPI were more likely to have aggravated social anxiety that would erode their work engagement in the organization.

The negative impact of WPI in the workplace such as on turnover intentions (Namin et al., 2022), job performance (Jiang et al., 2019) and work withdrawal (Bernard and Joe-Akunne, 2019) in many employee types such as civil servants in Malaysia (e.g., Alias et al., 2022), hospitality industry employees in Taiwan (Wang and Chen, 2020) and the USA (e.g., Im and Cho et al., 2022) showed the general far reaching effects of WPI. The specific findings in this study on WPI and work engagement could further incorporate the findings where job security mediated WPI and work engagement (Guo et al. 2022), making sense that WPI, especially by superiors, can negatively impact job security. Given that social anxiety was a partial factor, job security could also be studied together alongside suicidal ideation (Follmer and Follmer, 2021) to further make sense of other earlier studies on the role of anxiety or its various types. (e.g. Shi et al., 2018; De Clercq et al., 2020).

The analysis in our study showed age to be negatively correlated with WPI in support of literature (Han et al., 2021; Cortina et al., 2017) that employees experienced less WPI as they grow older. Younger and less experienced workers may face more WPI or that some form of work hazing may be present in many workplaces. Notably, we did not find any biological sex effects with WPI, that despite contradicting older literature finding that women (Cortina et al., 2017) or men (Lim and Lee, 2011) experienced more WPI, lends support to more recent findings (McCord et al. ,2018) that biological sex and ethnic biases have diminished over the years, at least as found in our sample.

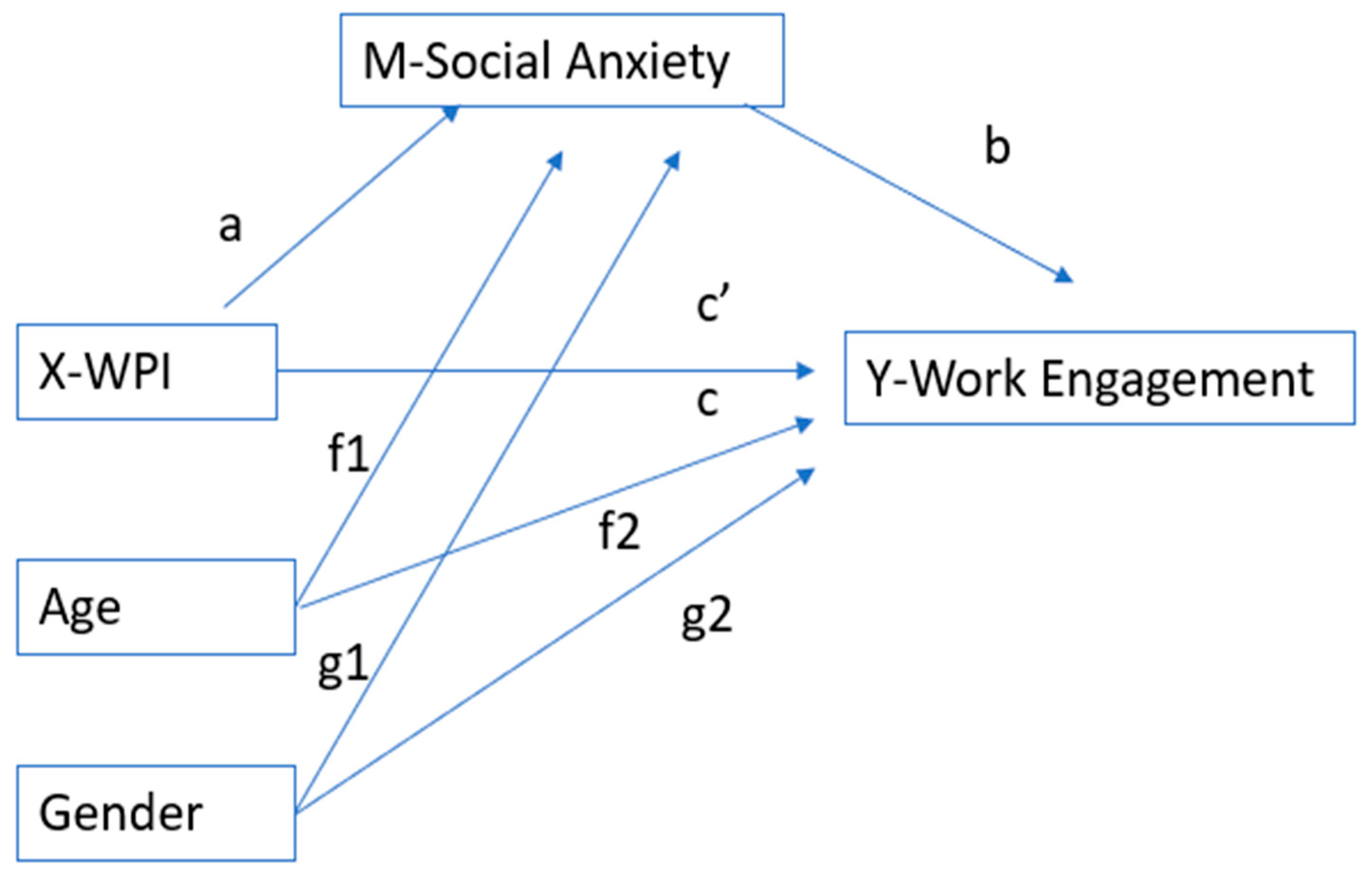

4. Materials and Methods

Design

The study utilized a cross-sectional correlational study with the dependent variable as work engagement and independent variable as WPI. The expected mediator was social anxiety, with both age and biological sex as covariates. The proposed mediation process is illustrated in

Figure 2 below.

Participants

G*Power computation suggested a minimum of 85 participants for a linear multiple regression (R2 deviation from zero) model: f2=.095 small effect size, .05 two-tailed alpha, .80 power and 4 predictors (WPI, social anxiety, work and covariates). The convenient recruitment strategy attracted 152 participants but 34 were removed as they did not provide informed consent (n=11) or did not answer two or more questions in the scales (n=23), resulting in a final number of 118 participants. The mean age (there were 5 missing data) was 33.7 years (SD=11.8, range 19 to 67) comprising of 57% females, 42% males and 1% non-binary. Ethnically, 79% were Chinese 12% Indians, and 8% Malays/Others. In terms of education, 68% reported at least a bachelor’s degree or higher, 31% with College/Diploma, and other qualifications at 1%. By industry, 89% of participants worked in the services industry, 11% were based on goods. 54% of the participants were office-based, 38% in hybrid work arrangements, and 8% working from home.

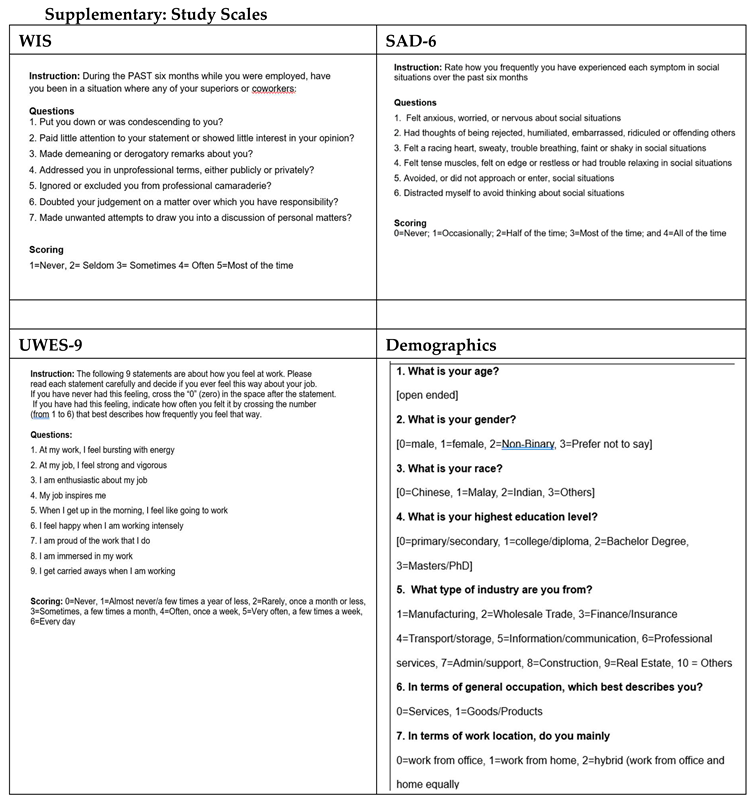

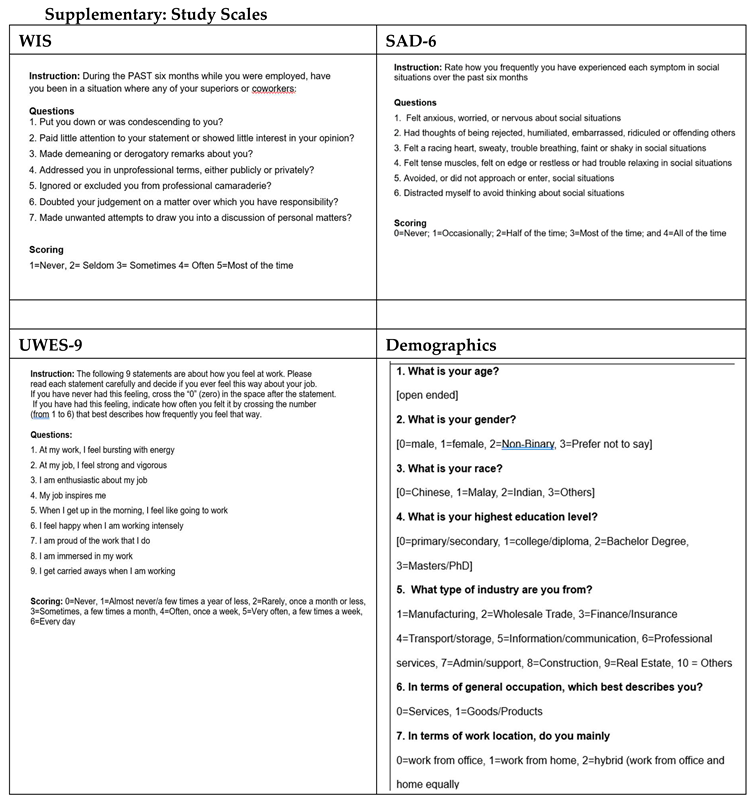

The Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS; Cortina et al., 2001) for WPI measurement was modified to reflect “general employment” instead of the “Eight Circuit Court” and a “6-month” instead of a “5-year” retrospective recall time period. The latter was modified for congruency with the time period for the social anxiety scale. The WIS comprised of seven questions: “have you been in a situation where any of your superiors or co-workers have…” (e.g., “put you down or was condescending towards you?”). All item responses were on a 5-point Likert Scale (1=Never to 5=Most of the time). The final score was computed as a mean ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores reflecting a higher WPI. The scale was previously used on the Singapore population by Lim and Lee (2011) which reported a Cronbach Alpha (α) of .91 (co-workers) to .92 (superiors). In the present study, α was .93, indicating excellent reliability.

The Brief DSM-5 Social Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale (SAD-6; Rice et al., 2021) had a time frame of the “past week” in the SAD-6 that was amended to the “past six months” in the present study. The amendment was unlikely to affect the measurement of social anxiety given that the SAD-6 is aligned with the DSM-5 which had a recommended span of six months to observe symptoms for social anxiety (Rice et al. 2021). The SAD-6 comprised of six questions where participants rated the frequency of their feelings in social situations over the past six months (e.g., “Felt anxious, worried or nervous about social situations”). All items were on a 5-point Likert Scale (0=Never to 4=All the time). Higher final mean scores reflected higher levels of social anxiety. The SAD-6 previously had a Cronbach (α) of .95 which was identical to the present study, indicating excellent reliability.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9 (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006) comprises of nine questions where participants rated the degree of engagement they felt at work (e.g., “My job inspires me”). All items were on a seven-point Likert scale (0=Never to 6=Every Day) and the final mean score ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of work engagement. The scale was validated in a study involving Singapore working parents of children with disabilities (Stefanidis and Strogilos, 2021). The present study’s Cronbach’s (α) of .95 was comparable to the original study’s .95.

Procedure

Upon ethics approval from the XXXX University Ethics Committee (XXXXX). A Research Data Management Plan was registered.

Participants were recruited through convenience sampling via digital advertisements on the university bulletin-board; the social media of the investigators; a public survey platform (Liew et al, 2020) and Facebook Survey Exchange for thesis projects (Facebook, n.d.). Working adults aged 18 years and above were invited to use a QR code/URL link which brought them to the ten-minute Qualtrics page online survey. The informed consent form had the information and clear instructions that the participants were free to discontinue the survey at any time without prejudice, but that once the submitted anonymous responses were submitted, they could not be identified for deletion. Participant data without complete informed consent were removed. Participants were asked to respond to the above-mentioned scales (WIS, SAD-6 and UWES-9) and some demographics questions modified from previous surveys (Gan et al., 2023; Wan et al. 2021; Gan, Loh, and Seet 2003) about age, biological sex, race, education, industry, occupation-type (e.g., services), and work location (e.g., home). The survey ended with a debriefing about the aims of the study and sources for psychological services if it was necessary. There were no benefits provided for the participation.

5. Conclusions

Organizations need to be mindful of WPI which can erode work engagement. Displayed social anxiety may be a useful early symptom of the general mental well-being of the employee in the workplace and lower levels of work engagement may be a manifestation of underlying issues relating to psychological well-being and mistreatment at work. It would be important for these to be addressed early for improved general employee experience.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of XXXX University (XXXX) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data is available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

References

- Adiyaman, Daniela, and Laurenz L. Meier. 2021. “Short-Term Effects of Experienced and Observed Incivility on Mood and Self-Esteem.” Work and Stress, September, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Shailja, Ritesh Pandey, Satish Kumar, Weng Marc Lim, Pankaj K. Agarwal, and Ashish Malik. 2023. “Workplace Incivility: A Retrospective Review and Future Research Agenda.” Safety Science 158 (February): 105990. [CrossRef]

- Alias, Mazni, Adedapo Oluwaseyi Ojo, and Nur Farhana Lyana Ameruddin. 2020. “Workplace Incivility: The Impact on the Malaysian Public Service Department.” European Journal of Training and Development ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Rasidah, and Ida RosnitaI Ismail. 2018. “Workplace Incivility and Knowledge Hiding Behavior: Does Personality Matter?” Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 5 (3): 278–88. [CrossRef]

- Beattie, Larissa, and Barbara Griffin. 2014. “Day-Level Fluctuations in Stress and Engagement in Response to Workplace Incivility: A Diary Study.” Work and Stress, April, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Chine, and Joe-Akunne, Chiamaka. 2019. Cyberloafing in the Workplace: A By-Product of Perceived Workplace Incivility and Perceived Workers’ Frustration. Scholars. Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 7, 308-317.

- Cheok, Thai-Shawn, Quek, Yuan-Sheng, Choo, Bryan, and Gan. Samuel Ken-En. 2020. What makes one civil? The associations between civility scores, gender, rational-experiential processing styles, self-consciousness and socioeconomic factors in Singapore. APD Trove, 3(3). https://studentjournal.apdskeg.com/studentjournals/article/4014.

- Chew, Agnes Si-Qi, Ya-Ting Yu, Si-Wei Chua, and Samuel Ken-En Gan. 2016. “The Effects of Familiarity and Language of Background Music on Working Memory and Language Tasks in Singapore.” Psychology of Music 44 (6): 1431–38. [CrossRef]

- Choo, Bryan Jun-Keat, Thai-Shawn Cheok, David Gunasegaran, Kum-Seong Wan, Yuan-Sheng Quek, Clare Shu-Lin Tan, Boon-Kiat Quek, and Samuel Ken-En Gan. 2020. “The Sound of Music on the Pocket: A Study of Background Music in Retail.” Psychology of Music, September, 030573562095847. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. “Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd.

- Ed.).” Journal of the American Statistical Association 84 (408): 1096. [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Lilia M., Dana Kabat-Farr, Vicki J. Magley, and Kerri Nelson. 2017. “Researching Rudeness: The Past, Present, and Future of the Science of Incivility.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22 (3): 299–313. [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Lilia M., Vicki J. Magley, Jill Hunter Williams, and Regina Day Langhout. 2001. “Incivility in the Workplace: Incidence and Impact.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6 (1): 64–80. [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Lilia M., M. Sandy Hershcovis, and Kathryn B. H. Clancy. 2021. “The Embodiment of Insult: A Theory of Biobehavioral Response to Workplace Incivility.” Journal of Management 48 (3): 014920632198979. [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Inam Ul Haq, and Muhammad Umer Azeem. 2019. “The Relationship between Workplace Incivility and Depersonalization towards Co-Workers: Roles of Job-Related Anxiety, Gender, and Education.” Journal of Management and Organization 26 (2): 219–40. [CrossRef]

- “Facebook.” n.d. Www.facebook.com. https://www.facebook.com/groups/1255012211233315.

- Follmer, Kayla B., and D. Jake Follmer. 2021. “Longitudinal Relations between Workplace Mistreatment and Engagement – the Role of Suicidal Ideation among Employees with Mood Disorders.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 162 (January): 206–17. [CrossRef]

- Gan, S. K. E., C. Y. Loh, and B. Seet. 2003. “Hypertension in Young Adults--an Under-Estimated Problem.” Singapore Medical Journal 44 (9): 448–52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14740773/.

- Gan, Samuel Ken-En, Keane Ming-Jie Lim, and Yu-Xuan Haw. 2015. “The Relaxation Effects of Stimulative and Sedative Music on Mathematics Anxiety: A Perception to Physiology Model.” Psychology of Music 44 (4): 730–41. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Samuel Ken-En, Sibyl Weang-Yi Wong, and Peng-De Jiao. 2023. “Religiosity, Theism, Perceived Social Support, Resilience, and Well-Being of University Undergraduate Students in Singapore during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20 (4): 3620. [CrossRef]

- Geldart, Sybil, Lacey Langlois, Harry S. Shannon, Lilia M. Cortina, Lauren Griffith, and Ted Haines. 2018. “Workplace Incivility, Psychological Distress, and the Protective Effect of Co-Worker Support.” International Journal of Workplace Health Management 11 (2): 96–110. [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, Christin, Norbert K. Semmer, Sabine Sauter, Alexandra Walker, Nathal de Wijn, Wolfgang Kälin, Maria U. Kottwitz, Bernd Kersten, Benjamin Ulrich, and Achim Elfering. 2021. “How Are Social Stressors at Work Related to Well-Being and Health? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Public Health 21 (1). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Ju, Yanjun Qiu, and Yongtao Gan. 2021. “Workplace Incivility and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Insecurity and the Moderating Role of Self-Perceived Employability.” Managerial and Decision Economics, May. [CrossRef]

- Han, Soojung, Crystal M. Harold, In-Sue Oh, Joseph K. Kim, and Anastasiia Agolli. 2021. “A Meta-Analysis Integrating 20 Years of Workplace Incivility Research: Antecedents, Consequences, and Boundary Conditions.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, October. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. Guilford Publications.

- Im, Angie Yeonsook, and Seonghee Cho. 2021. “Mediating Mechanisms in the Relationship between Supervisor Incivility and Employee Service Delivery in the Hospitality Industry.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 34 (2): 642–62. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Wenbo, Huaqi Chai, Yali Li, and Taiwen Feng. 2018. “How Workplace Incivility Influences Job Performance: The Role of Image Outcome Expectations.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 57 (4): 445–69. [CrossRef]

- Liew, Khye-Chun., Kui, Kenneth. W. J., Wu, Weiling., & Gan, Samuel Ken-En. 2020. Application Notes: PsychVey Ver2-Improving online survey data collection. Scientific Phone Apps and Mobile Devices, 6(5).

- Lim, Sandy, and Alexia Lee. 2011. “Work and Nonwork Outcomes of Workplace Incivility: Does Family Support Help?” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 16 (1): 95–111. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, Kim A. 2016. “Is Rudeness Really That Common? An Exploratory Study of Incivility at Work.” Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 26 (4): 364–74. [CrossRef]

- McCord, Mallory A, Dana L Joseph, Lindsay Y Dhanani, and Jeremy M Beus. 2018. “A Meta-Analysis of Sex and Race Differences in Perceived Workplace Mistreatment.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 103 (2): 137–63. [CrossRef]

- Namin, Boshra H., Torvald Øgaard, and Jo Røislien. 2021. “Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (1): 25. [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Julie. 2020. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using.

- IBM SPSS. 7th ed. S.L.: Open Univ Press.

- Reknes, Iselin, Guy Notelaers, Dragos Iliescu, and Ståle Valvatne Einarsen. 2021. “The Influence of Target.

- Personality in the Development of Workplace Bullying.” Journal of Occupational Health.

- Psychology 26 (4): 291–303. [CrossRef]

- Rice Kylie, Schutte Nicola S, Rock Adam J, Murray Clara V. 2021. Structure, Validity and Cut-Off Scores for the APA Emerging Measure of DSM-5 Social Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale (SAD-D). Journal of Depression and Anxiety. 10: 406.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Arnold B. Bakker, and Marisa Salanova. 2006. “The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 66 (4): 701–16. [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, Pauline, Irene E. De Pater, and Amir Erez. 2014. “Workplace Incivility: A Review of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 37 (1): S57–88. [CrossRef]

- Sherrod, Jayme Trocino, and Lynne Porter Lewallen. 2021. “Workplace Incivility and Its Effects on the Physical and Psychological Health of Nursing Faculty.” Nursing Education Perspectives 42 (5): 278–84. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Yu, Hui Guo, Shue Zhang, Fengzhe Xie, Jinghui Wang, Zhinan Sun, Xinpeng Dong, Tao Sun, and Lihua Fan. 2018. “Impact of Workplace Incivility against New Nurses on Job Burn-Out: A Cross-Sectional Study in China.” BMJ Open 8 (4): e020461. [CrossRef]

- Sood, Sarita, and Dhanvir Kour. 2022. “Perceived Workplace Incivility and Psychological Well-Being in Higher Education Teachers: A Multigroup Analysis.” International Journal of Workplace Health Management, September. [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, Abraham, and Vasilis Strogilos. 2020. “Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement of Employees with Children with Disabilities.” Personnel Review ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G, and Linda S Fidell. 2019. Using Multivariate Statistics. 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

- VAHLE-HINZ, Tim. 2019. “Little Things Matter: A Daily Diary Study of the Within-Person Relationship between Workplace Incivility and Work-Related Rumination.” Industrial Health, February. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, Anselmo Ferreira. 2020. “Workplace Incivility: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Workplace Health Management ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chih-Hung, and Hsi-Tien Chen. 2020. “Relationships among Workplace Incivility, Work Engagement and Job Performance.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). [CrossRef]

- Wan, Kum-Seong, Bryan Jun-Keat Choo, Kwok-Fong Chan, Joshua Yi Yeo, Clare Shu-Lin Tan, Boon-Kiat Quek, and Samuel Ken-En Gan. 2021. “Fear, Peer Pressure, or Encouragement: Identifying Levers for Nudging towards Healthier Food Choices in Multi-Cultural Singapore.” Www.preprints.org, November. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Jingxian, Sandy Lim, Cathy Yang Guo, Amy Y. Ou, and Jomel Wei Xuan Ng. 2021.

- A: Incivility in the Workplace; 51. “Experienced Incivility in the Workplace: A Meta-Analytical Review of Its Construct.

- Validity and Nomological Network.” Journal of Applied Psychology, April.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).