INTRODUCTION

Family planning (FP) has myriad health, social, and economic benefits for women, their families, and the nation. Family planning services can help improve maternal and child health and reduce unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions (Foreman & Player, 2013). Women are more likely to use family planning methods as educational and employment opportunities for women improve and they fully contribute to the economic well-being of the family (Kitula, 2017; Kassim, 2020). The correct use of contraceptive methods enables women to actively participate in family planning and at the same time to participate fully in working life. Family planning plays an important role in reducing malnutrition, improving child survival and maternal health (USAID, 2005). Several studies have also shown that promoting family planning reduces poverty, hunger, maternal and child mortality and contributes to the empowerment of women. Although there are different methods of birth control, there are two main categories: modern and traditional. Sterilization, intrauterine devices (IUDs), birth control implants, birth control injections, oral contraceptives, male and female condoms, emergency birth control pills, birth control patches, spermicidal foams and sponges are all modern birth control methods.

Hubacher and Trussell (2015) Calendar method, withdrawal, and folk methods (Marquez, Kabamalan & Laguna, 2017), cervical mucus and lactational amenorrhea methods are examples of traditional contraceptive methods (Almalik, Mosleh & Almasrwe, 2018). Other traditional methods of contraception that are particularly prevalent in Africa include virginity verification and the use of traditional medicines and herbs (Shange, 2012). (Keele, Forste & Flake, 2005). Various initiatives have been launched at global and local levels to increase the use of contraceptives. This includes the inclusion of family planning-related goals in Goals 3 and 5 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In addition, other strategies and action plans, such as the One Plan II 2016-2020 and the Health Sector Strategic Plan IV 2015-2020, prioritize contraception (UNFPA, 2019). Similarly, the 2006 National Population Policy and the 2017 National Health Policy emphasize the importance of educating the public about the importance of family planning (FP) and involving non-governmental stakeholders in the delivery of family planning services (URT, 2006; UR, 2017). Access to information about contraception is a key component of any family planning program.

According to UNFPA (2019), family planning is not only a collection of methods and tools for deciding whether one wants to have children, but also information about how and when to become pregnant. One of the essential components of the family is the availability of information about contraceptive methods. Much emphasis has been placed on understanding family method preferences (Safari et al., 2019) as well as knowledge and awareness about contraceptive methods (Kapiga, Hunter & Nachtigal, 1992; Msoffe & Kiondo 2009; Kara, Benedicto & Mao, 2019). There is a need to identify factors that either facilitate or hinder married women's decision to access contraceptive information to support family planning. Information about contraceptives is crucial for women who want to avoid unwanted pregnancies and thus help reduce induced or unsafe abortions. In their theory of information worlds, Jaeger and Burnett (2010) proposed a holistic approach to information access. Access to information about contraceptive methods for family planning has the potential not only to increase contraceptive acceptance, but also to make informed decisions about highly effective and trustworthy methods.

METHODS

Study area

The research was conducted in Better Life Primary Healthcare Centre, Ondo City, Ondo State Nigeria. The Better Life Primary Health Centre is located at Okelisa/Okedoko, Ondo West Local Government, Ondo State. It was established on 1st January 2007 and operates on 24 hours basis. The Better Life Primary Health Centre is licensed hospital by the Nigeria Ministry of Health and registered as Primary Health Care Centre. Ondo City is the second largest town in Ondo State, Nigeria.

Study population

This study comprises of ninety-one (91) women who came to the health centre for family planning services utilization at Better Life Primary Healthcare Centre, Ondo City, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Study design and sampling

This study was a cross – sectional descriptive study. A systematic random sampling was used in selecting ninety-one (91) participants for this study.

Data collection methods

The data was collected from ninety-one (91) participants using appropriate tools. The data comprises of two sections namely socio-demographic characteristics and information on the various contraceptive services they utilized during their visit to the Better Life Primary Healthcare Centre for planning services.

Data analysis

The results were analysed using Statistical Package for Service Solutions (SPSS) Version 21. The results were presented in percentage and frequency.

Ethical consideration

Approval to conduct this research was obtained from the coordinator of the primary healthcare centre. Informed consents were obtained from the participants and their confidentiality was ensured.

DISCUSSION

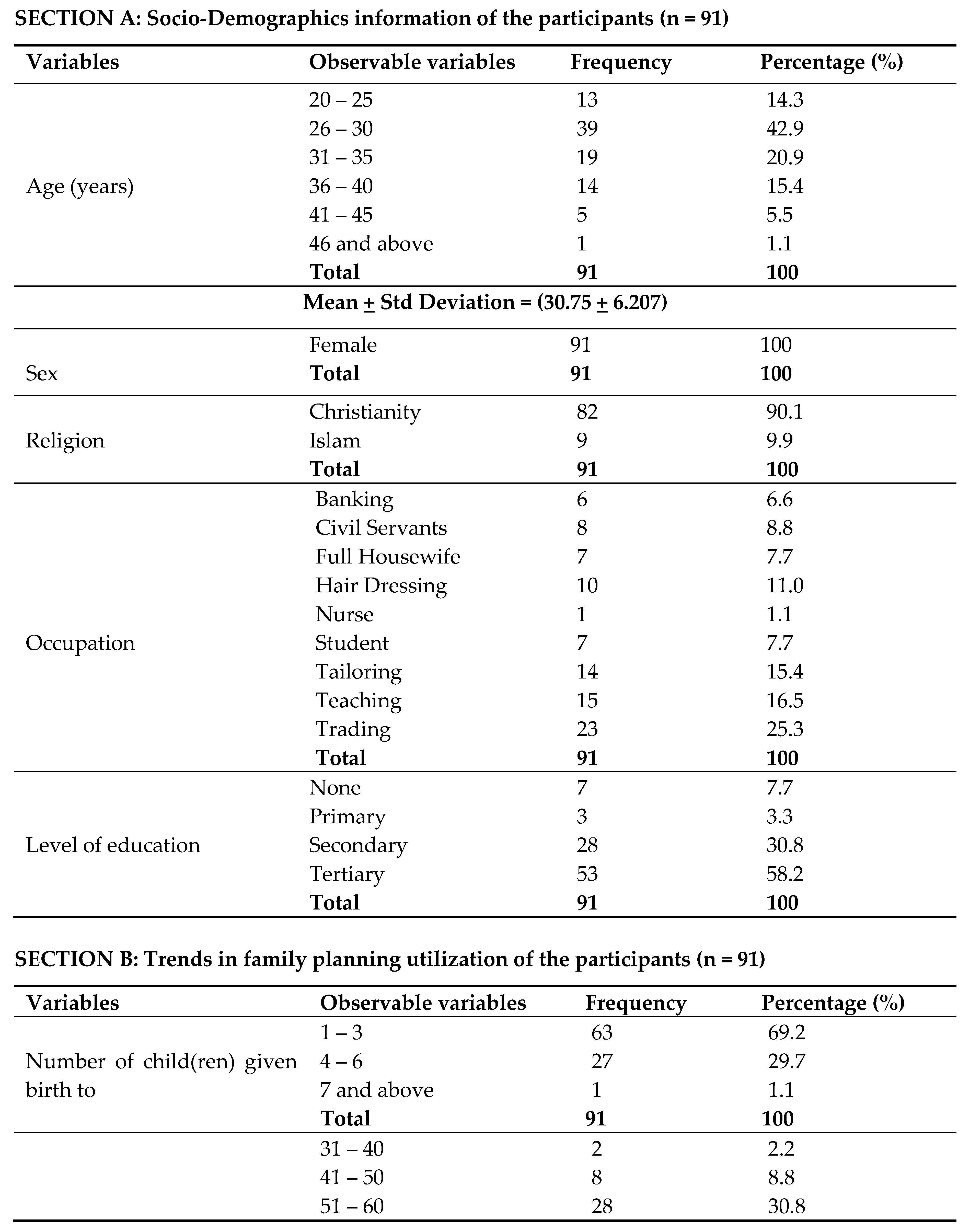

Socio-Demographics information of the participants (n = 91)

The table above shows that the mean age and standard deviation of the respondents were (30.75 + 6.207) and 39 (42.9%) were between 26 – 30 years old, 91 (100%) were females, 82 (90.1%) were Christians, 23 (25.3 %) were traders and 53 (58.2%) had tertiary education.

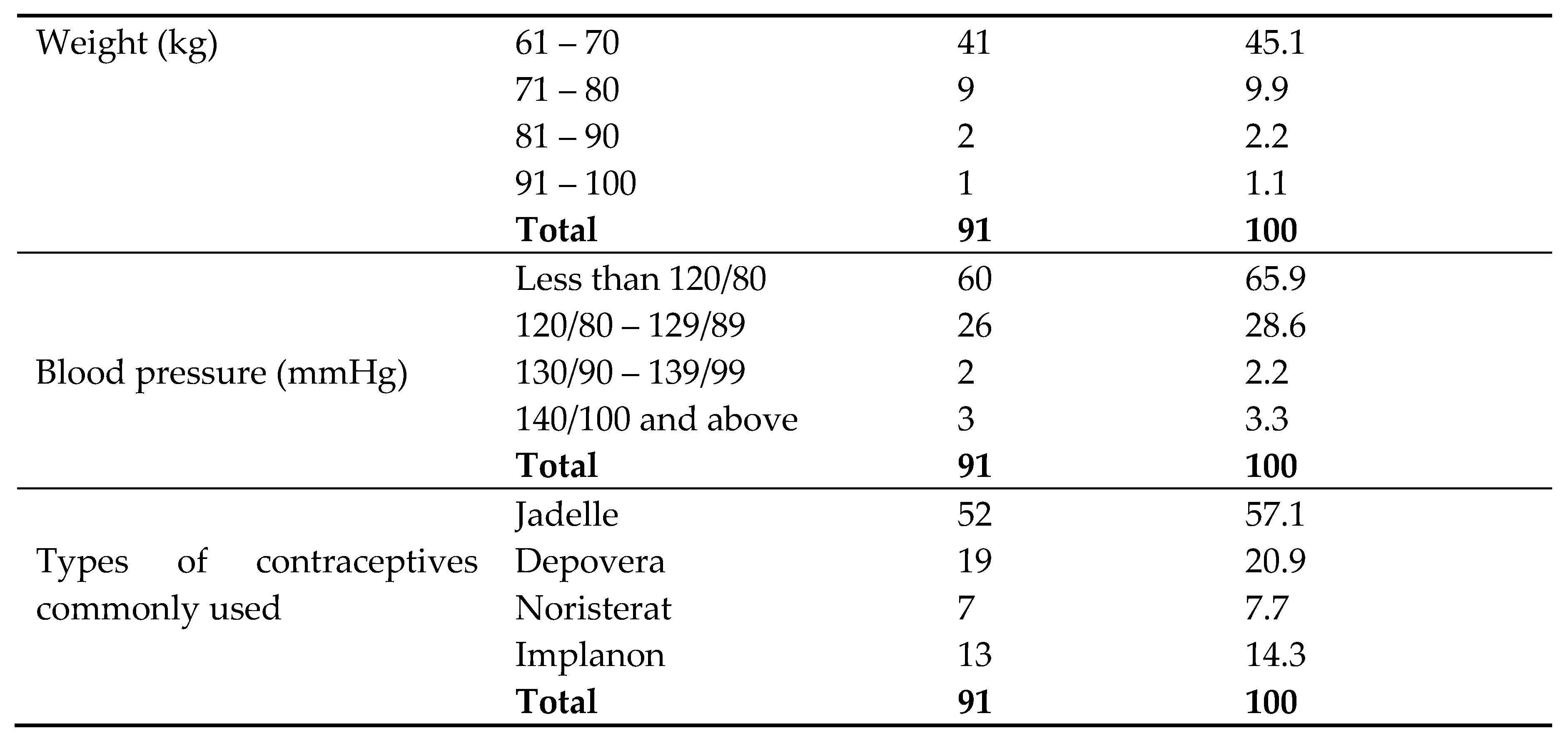

Trends in family planning utilization among the participants (n = 91)

27 (29.7%) had 1 – 3 children, 41 (45.1%) weighed between 60 – 70kg, 60 (65.9%) had blood pressure less than 120/80mmHg and 52 (57.1%) utilized Jadelle contraceptive for their family planning services.

CONCLUSION

The benefits of family planning to individuals, families, communities, and society underscore its importance. Family planning (FP) has a plethora of health, social, and economic benefits. Family planning services can reduce malnutrition, infant and maternal morbidity and mortality, unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infections, address the problem of sexually transmitted infections, reduce infertility rates, and improve maternal and newborn health. All efforts and programs aimed at encouraging the use of family planning services by women of childbearing potential in the community should be encouraged.

References

- Almalik, M.; Mosleh, S.; Almasarweh, I. Are users of modern and traditional contraceptive methods in Jordan different? East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2018, 24, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, M. & Spieler, J. (2013). Contraceptive evidence: Questions and Answers. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

- Hubacher, D.; Trussell, J. A definition of modern contraceptive methods. Contraception 2015, 92, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, P.T. & Burnett, G. (2010). Information Worlds: Social Context, Technology, and Information Behavior in the Age of the Internet. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kapiga, S.H.; Hunter, D.J.; Nachtigal, G. Reproductive knowledge, and contraceptive awareness and practice among secondary school pupils in Bagamoyo and Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Central Africa Journal of Medicine 1992, 38, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, W.S.K.; Benedicto, M.; Mao, J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Contraception Methods Among Female Undergraduates in Dodoma, Tanzania. Cureus 2019, 11, e4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassim, M. A qualitative study of the maternal health information-seeking behaviour of women of reproductive age in Mpwapwa district, Tanzania. Heal. Inf. Libr. J. 2020, 38, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keele, J.J.; Forste, R.; Flake, D.F. Hearing Native Voices: Contraceptive Use in Matemwe Village, East Africa. Afr. J. Reprod. Heal. 2005, 9, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitula, M.D.N. Women status and culture on contraceptive use: The case of Mbeya and Pwani regions. Huria Journal of the Open University of Tanzania 2017, 24, 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, M. P. N., Kabamalan, M., & Laguna, E. P. (2017). Ten years of traditional contraceptive method use in the Philippines: Continuity and change. ICF.

- Msoffe, G.E.; Kiondo, E. Accessibility and use of family planning information (FPI) by rural people in Kilombero District, Tanzania. African Journal of Library Archives Information Science 2009, 19, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ndumbaro, F.; Ochieng, L.M. Access to Information on Family Planning (FP) Methods Among Married Women of Reproductive Age in Ilala District, Dar es Salaam Tanzania. University of Dar es Salaam Library Journal 2021, 16, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, W.; Urassa, M.; Mtenga, B.; Changalucha, J.; Beard, J.; Church, K.; Zaba, B.; Todd, J. Contraceptive use and discontinuation among women in rural North-West Tanzania. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2019, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shange, T. (2012). Indigenous methods used to prevent teenage pregnancy: Perspectives of traditional healers and traditional leaders. Unpublished Master’s Dissertation. University of Kwazulu Natal, Durban, South Africa.

- UNFPA. (2019). 5 Upsetting Reasons Women Aren’t Using Family Planning Around the World Today. Available online: https://www.friendsofunfpa.org/5-upsetting-reasons-women-arent-using-family-planning-around-the-world-today/ (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- URT. (2006). National Health Policy 2017. Dar es Salaam: MHCDGE.

- URT. (2006). National Population Policy 2006. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of planning, economy and empowerment.

- URT. (2016). The national road map strategic plan to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in Tanzania (2016 - 2020): One plan II.

- USAID. (2005). Strengthening Family Planning Policies and Programs in Developing Countries: An advocacy toolkit. The Policy Project. Available online: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadh039.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).