Submitted:

09 October 2023

Posted:

10 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

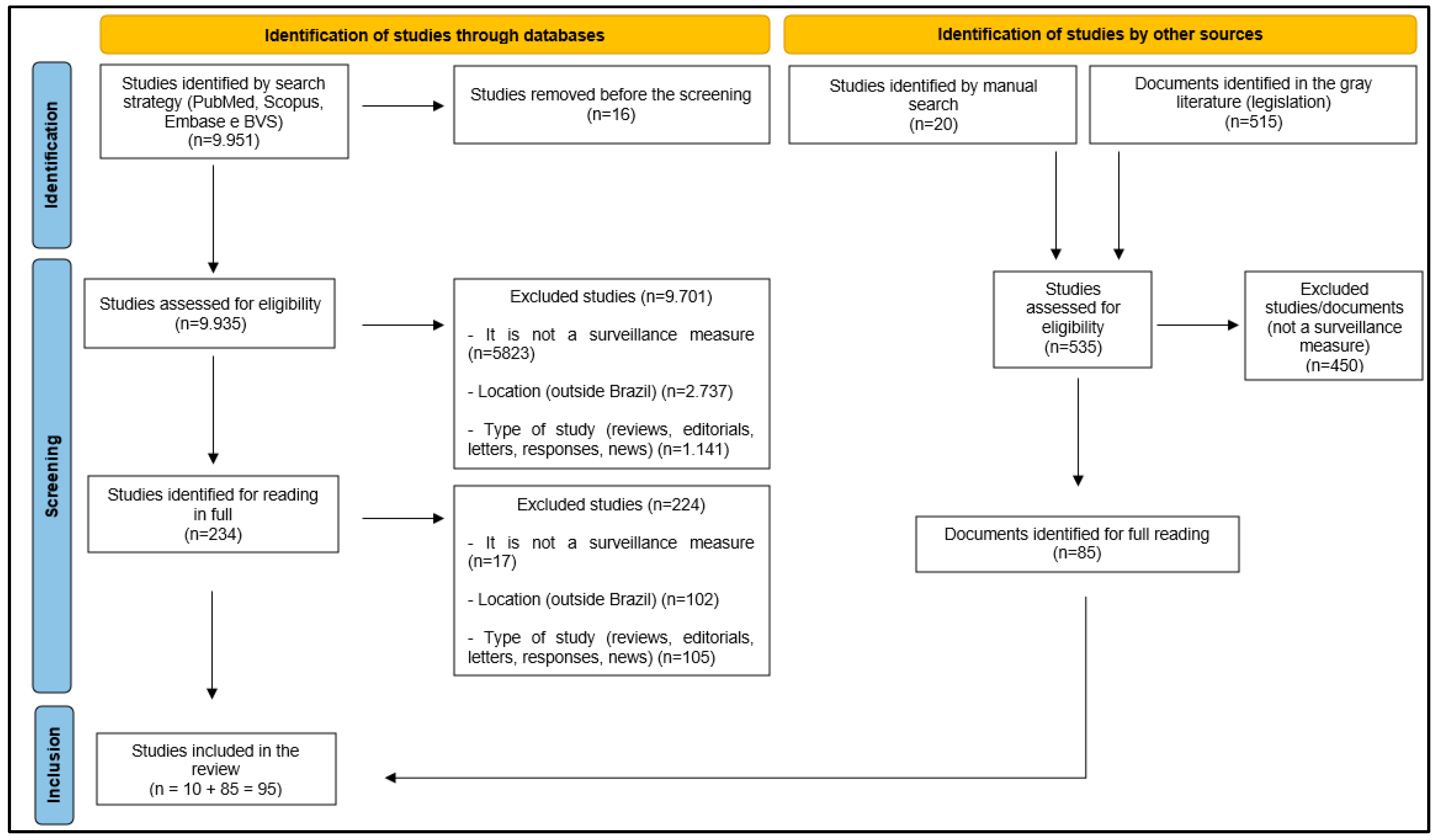

2. Method

2.1. Data Sources and Research Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Period

2.4. Study Selection

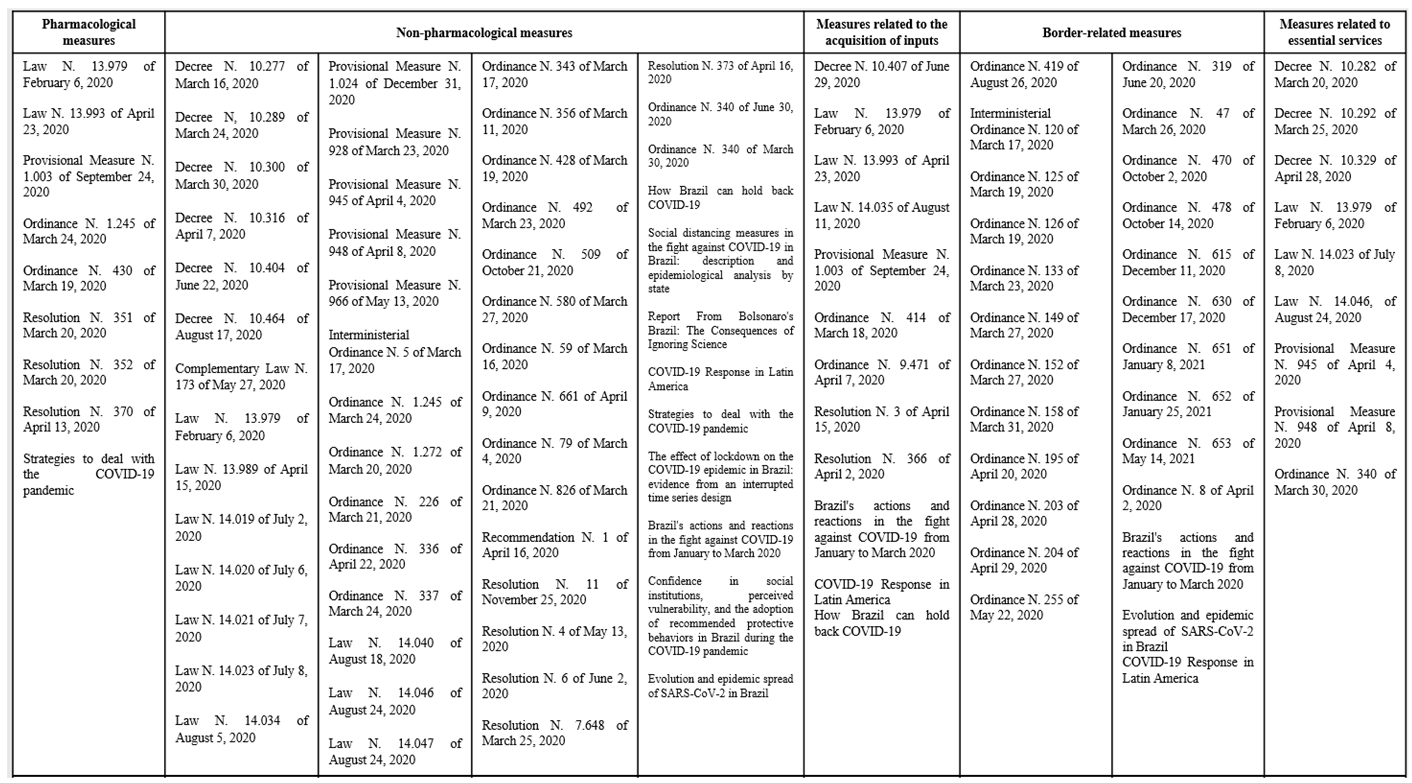

3. Results

3.1. Measures related to international borders

3.2. Pharmacological Measures

3.3. Measures related to supply acquisition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Garfin D, Silver R, Holman E. O novo surto de coronavírus: amplificação das consequências para a saúde pública pela exposição à mídia. Health Psychol [publicação online] 2020 [acesso em 5 jan 2021].

- WHO. Relatório da situação 11 [Internet]. WHO. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 29].

- Perlman S. Outra década, outro coronavírus. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:760-762.

- Paterlini M.A linha de frente do Coronavirus: a resposta italiana à COVID-19. The BMJ. 2020;368.

- Block P, Hoffman M, Raabe I, Beam Dowd J, Rahal C, Kashyap R, et al. Social network-based distancing strategies to flatten the COVID-19 curve in a post-lockdown world. Nat Human Behaviour. 2020;4; 4:588–96. [CrossRef]

- Arshed N, Meo MS, Farooq F. Empirical assessment of government policies and flattening of the COVID 19 curve. J Public Aff. 2020; e2333. [CrossRef]

- Jesus JG, de Sacchi C, Candido D da S, Claro IM, Sales FCS, Manuli ER, et al. Importation and early local transmission of COVID-19 in Brazil. Rev Ins Med Trop São Paulo. 2020;62. [CrossRef]

- Croda J, Oliveira WK de, Frutuoso RL, Mandetta LH, Baia-da-Silva DC, Brito-Sousa JD, et al. COVID-19 in Brazil: advantages of a socialized unified health system and preparation to contain cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop [publicação online]. 2020 [acesso em 25 set 2020];53. [CrossRef]

- Freitas CM de, Silva IV de M e, Cidade N da C, Freitas CM de, Silva IV de M e, Cidade N da C. COVID-19 AS A GLOBAL DISASTER: Challenges to risk governance and social vulnerability in Brazil. Ambiente & Sociedade [publicação online]. 2020 [acesso em 25 jul 2021];23.

- Aquino EML. Medidas de distanciamento social no controle da pandemia de COVID-19: Potenciais impactos e desafios no Brasil [publicação online]. 2020 [acesso em Mar 3 2022].

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n° 188, de 3 de Fevereiro De 2020. Declara Emergência em Saúde Pública de importância Nacional (ESPIN) em decorrência da Infecção Humana pelo novo Coronavírus (2019-nCoV). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews [publicação online]. 2016 [acesso em 5 set 2021];5(1). [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. PRISMA [Internet]. Prisma-statement.org. 2020.

- Ministério da Saúde. Lei nº 13.989, de 15 de abril de 2020.Dispõe sobre o uso da telemedicina durante a crise causada pelo coronavírus (SARS-CoV-2). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº156, de 1 de abril de 2020. Suspende, temporária e excepcionalmente, o tempo máximo para o contato direto com o atendente no Serviço de Atendimento ao Consumidor - SAC, previsto na Portaria nº 2.014, de 13 de outubro de 2008, do Ministério da Justiça. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Plano de Contingência Nacional para Infecção Humana pelo novo Coronavírus COVID-19 2020. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 59, de16 de março de 2020. Fica instituído o Gabinete Integrado de Acompanhamento à Epidemia do Coronavírus-19 (GIAC-COVID19). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Decreto n° 10.277, de 16 de março de 2020. Institui o Comitê de Crise para Supervisão e Monitoramento dos Impactos da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Educação. Portaria nº 343, de 17 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a substituição das aulas presenciaispor aulas em meios digitais enquanto durar a pandemia do novo coronavírus. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº428, de 19 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre as medidas de proteção para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus (COVID-19) no âmbito das unidades do Ministério da Saúde no Distrito Federal e nos Estados. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº 492,de 23 de Março de 2020. Institui a Ação Estratégica "O Brasil Conta Comigo", voltada aos alunos dos cursos da área de saúde, para o enfrentamento à pandemia do coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto nº 10.316, de 7 de abril de 2020. Regulamenta a Lei nº 13.982, de 2 de abril de 2020, que estabelece medidas excepcionais de proteção social a serem adotadas durante o período de enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus. Diário Oficial da União.

- Presidência da República SG. Lei nº 14.046, de 24 de agosto de 2020.Planalto.gov.br. 2022. Dispõe sobre medidas emergenciais para atenuar os efeitos da crise decorrente da pandemia da COVID-19 nos setores de turismo e de cultura. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Lei nº 14.019, de 2 de julho de 2020. Altera a Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, para dispor sobre a obrigatoriedade do uso de máscaras de proteção individual para circulação em espaços públicos e privados acessíveis ao público, em vias públicas e em transportes públicos, sobre a adoção de medidas de assepsia de locais de acesso público, inclusive transportes públicos, e sobre a disponibilização de produtos saneantes aos usuários durante a vigência das medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente da pandemia da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Lei nº 14.021, de 7 de julho de 2020. Dispõe sobre medidas de proteção social para prevenção do contágio e da disseminação da COVID-19 nos territórios indígenas; cria o Plano Emergencial para Enfrentamento à COVID-19 nos territórios indígenas; estipula medidas de apoio às comunidades quilombolas, aos pescadores artesanais e aos demais povos e comunidades tradicionais para o enfrentamento à COVID-19; e altera a Lei nº 8.080, de 19 de setembro de 1990, a fim de assegurar aporte de recursos adicionais nas situações emergenciais e de calamidade pública. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Resolução nº 11, de 25 de novembro de 2020. Institui Grupo de Trabalho para a coordenação das medidas de proteção e a prestação de contas de benefícios, em resposta aos impactos relacionados ao coronavírus, no âmbito do Comitê de Crise da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº125, de 19 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a restrição excepcional e temporária de entrada no País de estrangeiros oriundos dos países que relaciona, conforme recomendação da Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária - Anvisa. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 125, de 19 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a restrição excepcional e temporária de entrada no País de estrangeiros oriundos dos países que relaciona, conforme recomendação da Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária - Anvisa. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria n°126, de 19 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a restrição excepcional e temporária de entrada no País de estrangeiros oriundos dos países que relaciona, conforme recomendação da Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – Anvisa. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº 47, de 26 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a restrição excepcional e temporária de entrada no País de estrangeiros por transporte aquaviário, conforme recomendação da Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – Anvisa. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº158, de 31 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a restrição temporária e excepcional de entrada no País de estrangerios provenientes da República Bolivariana da Venezuela.Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Resolução - Rdc nº 351, de 20 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a atualização do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial) da Portaria SVS/MS nº 344, de 12 de maio de 1998, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 356, de 11 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a regulamentação e operacionalização do disposto na Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, que estabelece as medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Autoriza o Poder Executivo federal a aderir ao Instrumento de Acesso Global de Vacinas COVID-19 - Covax Facility. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Medida Provisória nº 1.026, de 6 de janeiro de 2021. Dispõe sobre as medidas excepcionais relativas à aquisição de vacinas, insumos, bens e serviços de logística, tecnologia da informação e comunicação, comunicação social e publicitária e treinamentos destinados à vacinação contra a COVID-19 e sobre o Plano Nacional de Operacionalização da Vacinação contra a COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº414, de 18 de março de 2020. Autoriza a habilitação de leitos de Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Adulto e Pediátrico, para atendimento exclusivo dos pacientes COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria n° 430, de 30 de dezembro de 2020. Ficam divulgados os dias de feriados nacionais e estabelecidos os dias de ponto facultativo no ano de 2021, para cumprimento pelos órgãos e entidades da Administração Pública federal direta, autárquica e fundacional do Poder Executivo, sem prejuízo da prestação dos serviços considerados essenciais. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Portaria nº 9.471 de 07 de abril de 2020. Estabelece medida extraordinária e temporária quanto à comercialização de Equipamentos de Proteção Individual - EPI de proteção respiratória para o enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública decorrente do Coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Resolução nº 3, de 15 de abril de 2020. Institui Grupo de Trabalho para a Coordenação de Ações Estratégicas para Construção de Hospitais de Campanha Federais e Logística Internacional de Equipamentos Médicos e Insumos de Saúde, em resposta aos impactos relacionados ao coronavírus, no âmbito do Comitê de Crise da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Decreto No 10.407 De 29 De Junho De 2020. Regulamenta a Lei nº 13.993, de 23 de abril de 2020, que dispõe sobre a proibição de exportações de produtos médicos, hospitalares e de higiene essenciais ao combate à epidemia da COVID-19 no País. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria Gm/Ms nº 197, de 1 de fevereiro de 2021. Delega competência ao Diretor do Departamento de Logística em Saúde do Ministério da Saúde, para realizar requisição de medicamentos, equipamentos, imunobiológicos e outros insumos de interesse para saúde, durante a vigência da declaração de emergência em saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Infraestrutura. Portaria nº 199, de 10 de fevereiro de 2021. Dispõe sobre os prazos de processos e de procedimentos afetos aos órgãos e entidades do Sistema Nacional de Trânsito e às entidades públicas e privadas prestadoras de serviços relacionados ao trânsito, por força das medidas de enfrentamento da pandemia de COVID-19 no Estado do Amazonas. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ministério da Saúde.Lei nº 14.035, De 11 De Agosto De 2020. Altera a Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, para dispor sobre procedimentos para a aquisição ou contratação de bens, serviços e insumos destinados ao enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus responsável pelo surto de 2019. Diário Oficial da União.

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-PRISMA. [Homepage da internet]. Prisma-statement.org. [acesso em 30 set 2021].

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020. Dispõe sobre as medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus responsável pelo surto de 2019. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República.Portaria Interministerial nº 5, de 17 de março de 2020.Dispõe sobre a compulsoriedade das medidas de enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública previstas na Lei nº 13.979, de 06 de fevereiro de 2020. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Portaira nº 1272GM-MD, de 20 de março de 2020. Aprovação da Diretriz Ministerial de Execução nº 7/2020, que autoriza a execução das ações de apoio para mitigar os impactos do COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Medida provisória no 966, de 13 de maio de 2020. Dispõe sobre a responsabilização de agentes públicos por ação e omissão em atos relacionados com a pandemia da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República.Resolução no 6, de 2 de junho de 2020. Institui Grupo de Trabalho para a Consolidação das Estratégias de Governança e Gestão de Riscos do Governo federal em resposta aos impactos relacionados ao coronavírus, no âmbito do Comitê de Crise da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. Lei no 14.019, de 2 de julho de 2020. Altera a Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, para dispor sobre a obrigatoriedade do uso de máscaras de proteção individual para circulação em espaços públicos e privados acessíveis ao público, em vias públicas e em transportes públicos, sobre a adoção de medidas de assepsia de locais de acesso público, inclusive transportes públicos, e sobre a disponibilização de produtos saneantes aos usuários durante a vigência das medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente da pandemia da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República. DECRETO Nº 10.282, DE 20 DE MARÇO DE 2020. Regulamenta a Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, para definir os serviços públicos e as atividades essenciais. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil.Secretaria Geral da Presidência da República.Plano de Contingência Nacional para Infecção Humana pelo novo Coronavírus COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União.

- Tang W, Cao Z, Han M, Wang Z, Chen J, Sun W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2020 May 14; m1849. [CrossRef]

- Garcia LP, Duarte E. Intervenções não farmacológicas para o enfrentamento à epidemia da COVID-19 no Brasil. Epidemiol Serv Saude.2020 Apr 9;29:e2020222.

- Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Vigilância em Saúde. Diário Oficial da União.

- Nadanovsky P, Santos App dos. Strategies to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34.

- World Health Organization - Who. Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in healthcare settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Diário Oficial da União.

- Ortega F, Orsini M. Governing COVID-19 without government in Brazil: Ignorance, neoliberal authoritarianism, and the collapse of public health leadership. Glob Public Health. 2020 Jul 14;1–21. [CrossRef]

- Marson FAL. COVID-19 – Six million cases worldwide and an overview of the diagnosis in Brazil: A tragedy to be announced. Diagnostic Microbiol and Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;115113.

- Romero M, Passos L. COVID-19 in Brazil: “So what?”. The Lancet [ revista em internet] 2020. [acesso em Janeiro 2021]; 32(2).

- Cornwall W. Can you put a price on COVID-19 options? Experts weigh lives versus economics [revista em internet] 2020.

- Agência Lupa [homepage na internet]. Após mudança de discurso do presidente, redes bolsonaristas elogiam vacinação [acesso em Mar 4 2022].

- Aguiar P. Toda e qualquer vacina está descartada.R7.com.[revista em internet] 2020.

- Lima LD, Pereira AM, Machado CV. Crise, condicionantes e desafios de coordenação do Estado federativo brasileiro no contexto da COVID-19. [publicação online];2020[acesso em 14 jan 2021].

- Homero V. Butantan entregará 46 milhões de doses da CoronaVac até abril, diz Pazuello [publicação online]; 2021 [acesso em 4 mar 2022].

- Costa D CAR, Bahia L, Carvalho EMCL de, Cardoso AM, Souza PMS. Oferta pública e privada de leitos e acesso aos cuidados à saúde na pandemia de COVID-19 no Brasil.Saúde em Debate [publicação online]; 2020 [acesso em 5 jan 2021].

| Database | Search syntaxes |

|---|---|

| PUBMED | ("public health surveillance"[MeSH Terms] OR "public health surveillance"[Title/Abstract] OR "epidemiological monitoring"[Title/Abstract] OR "Epidemiology"[MeSH Terms] OR "Epidemiology"[Title/Abstract] OR "health services research"[MeSH Terms] OR "communicable disease control"[MeSH Terms] OR (("prevent"[All Fields] OR "preventability"[All Fields] OR "preventable"[All Fields] OR "preventative"[All Fields] OR "preventatively"[All Fields] OR "preventatives"[All Fields] OR "prevented"[All Fields] OR "preventing"[All Fields] OR "prevention and control"[MeSH Subheading] OR ("prevention"[All Fields] AND "control"[All Fields]) OR "prevention and control"[All Fields] OR "prevention"[All Fields] OR "prevention s"[All Fields] OR "preventions"[All Fields] OR "preventive"[All Fields] OR "preventively"[All Fields] OR "preventives"[All Fields] OR "prevents"[All Fields]) AND "control groups"[MeSH Terms]) OR "prophylaxis"[Title/Abstract] OR "preventive measures"[Title/Abstract] OR “prevention"[Title/Abstract] OR "control"[Title/Abstract] OR "health policy"[MeSH Terms] OR "health policy"[Title/Abstract] OR (("Policy"[MeSH Terms] OR "Policy"[All Fields] OR "policies"[All Fields] OR "policy s"[All Fields]) AND "national health"[Title/Abstract])) AND ("coronavirus infections"[MeSH Terms] OR "betacoronavirus"[MeSH Terms] OR "epidemics"[MeSH Terms] OR "epidemic*"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("brazil"[MeSH Terms] OR "brazil"[All Fields] OR "brazil s"[All Fields] OR "brazils"[All Fields] OR (("ministries"[All Fields] OR "ministry"[All Fields] OR "ministry s"[All Fields]) AND ("Health"[MeSH Terms] OR "Health"[All Fields] OR "health s"[All Fields] OR "healthful"[All Fields] OR "healthfulness"[All Fields] OR "healths"[All Fields])) OR (("Health"[MeSH Terms] OR "Health"[All Fields] OR "health s"[All Fields] OR "healthful"[All Fields] OR "healthfulness"[All Fields] OR "healths"[All Fields]) AND ("Epidemiology"[MeSH Subheading] OR "Epidemiology"[All Fields] OR "Surveillance"[All Fields] OR "Epidemiology"[MeSH Terms] OR "surveilance"[All Fields] OR "surveillances"[All Fields] OR "surveilled"[All Fields] OR "surveillence"[All Fields]) AND ("secretariat"[All Fields] OR "secretariat s"[All Fields] OR "secretariats"[All Fields]))) |

| Scopus | Brazil OR ministry AND of AND health OR health AND surveillance AND secretariat AND public AND health AND surveillance OR public AND health AND surveillance OR epidemiological AND monitoring OR epidemiology OR health AND services AND research OR communicable AND disease AND control OR prevention AND control OR control AND groups OR prophylaxis OR preventive AND measures OR prevention OR control OR health AND policy OR policy OR national AND health AND betacoronavirus OR coronavirus AND infections OR COVID-19 OR covid19 OR coronavirus AND disease 2019 OR sars AND cov 2 infection OR covid 19 pandemic OR sars-cov-2 OR coronavirus 2 sars OR severe AND acute AND respiratory OR syndrome AND coronavirus 2 |

| Virtual Health Library (VHL) | (Brasil ) OR (Ministério da Saúde ) OR (Secretaria de Vigilância de Saúde)) AND ((mh:(Vigilância em saúde pública )) OR (Vigilância em saúde pública) OR (mh:(Monitoramento Epidemiológico)) OR (Vigilância Epidemiológica) OR (Monitoramento Epidemiológico) OR (Vigilâncias Epidemiológicas) OR (mh:(Pesquisa de Serviços de Saúde)) OR (Pesquisa de Serviços de Saúde) OR (mh:(Prevenção e controle)) OR (Prevenção e controle) OR (mh:(Controle de Doenças Transmissíveis)) OR (Controle de Doenças Transmissíveis) OR (profilaxia) OR (terapia preventiva ) OR (medidas preventivas ) OR (prevenção *) OR (controle) OR (mh:(Polícia da saúde)) OR (Polícia da saúde) OR (Política de Saúde ) OR (Políticas Nacionais de Saúde)) AND ((mh:(Betacoronavirus)) OR (Betacoronavirus) OR (mh:(COVID-19)) OR (COVID-19) OR (COVID 19) OR (Doença pelo Novo Coronavírus (2019-nCoV)) OR (Infecção por Coronavirus 2019-nCoV) OR (Surto por Coronavírus 2019-nCoV) OR (SARS-CoV-2 ) OR (SARS-CoV-2 ) OR (Síndrome Respiratória Grave Aguda)) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).