Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a helical-shaped bacterium, constitutes a significant etiological factor in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcers, specific manifestations of gastric cancer, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (1). There is ongoing debate surrounding its potential association with conditions like cardiovascular disease and ischemic stroke (2).

The conventional approach for addressing H. pylori infection is eradication therapy, typically involving combinations of two to three antibiotics in conjunction with a proton-pump inhibitor (3,4). This therapeutic regimen not only fosters the healing of peptic ulcers and prevents their recurrence but also reduces the risk of gastric cancer (5).

From a public health perspective, H. pylori presents a critical pathogenic concern. In 2018, it was estimated that approximately 800,000 new cases of gastric cancer worldwide were attributed to H. pylori infection (6). Furthermore, the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study projected an annual mortality rate of 3.5 deaths per 100,000 population due to peptic ulcer disease (7), for which H. pylori serves as a primary risk factor (8,9). Additionally, studies conducted among Japanese-American men have demonstrated that H. pylori infection is associated with 3.0 to 4.7 times higher odds of developing peptic ulcer disease compared to their counterparts.

Clearly, H. pylori prevalence displays significant variability across different geographic regions, population groups, and time periods. A systematic review encompassing global H. pylori prevalence data estimated that in 2015, approximately 4.4 billion individuals worldwide were affected by H. pylori infection (10). This comprehensive review of prevalence data from 62 countries revealed substantial disparities in H. pylori prevalence among diverse geographic regions, with Africa reporting the highest prevalence (70.1%; 95% CI [62.6–77.7]) and Oceania the lowest (24.4%; 95% CI [18.5–30.4]) (10). Another systematic review examining global H. pylori prevalence documented wide-ranging variations between countries, with prevalence rates ranging from 13.1% in Finland to a staggering 90% in Mexico (11). Moreover, investigations consistently identified disparities within countries, with higher H. pylori prevalence often observed in vulnerable populations, including migrants and Indigenous communities (12).

In the African context, H. pylori prevalence exhibits distinct regional variations and is influenced by a multitude of factors such as age, literacy levels, dietary habits, and geographic location. For example, Nigeria exhibits notable variance in prevalence, with rates as high as 87.8% reported in the northern regions (13), while the southeast and south-south geopolitical zones report prevalence rates of 34.2% and 51.4% among the adult population and 36.3% and 42.6% among children, respectively (14-15). Conversely, prevalence rates of 6.0% and 28% have been recorded in children from the north-central and southwestern regions of Nigeria, respectively (16). The elevated prevalence in certain areas has been associated with risk factors such as low socioeconomic status, limited access to clean water, overcrowding, cigarette smoking, and heightened levels of interferon-gamma (17, 18, 15).

Across various African nations, a range of H. pylori prevalence rates has been reported, highlighting the heterogeneity of the infection’s distribution. Rates include 70.8% in Burundi (19), 75% in Rwanda in 2014, with 20.1% of cases presenting with ulcers, 10% with gastric obstruction, and 4.5% with malignancy (19), 70.41% and 93.1% in 2015, respectively, in Togo (20) and Congo Brazzaville (21,22), 63.8% in Morocco (23), 88% in Ghana (24), and 66.12% in Egypt in 2019 (25). Notably, Egypt reported a prevalence of 64.6% among children with risk factors such as overcrowding, patronizing food vendors, and limited literacy (26). In the Republic of Benin, a prevalence rate of 71.5% was recorded, with no significant associations with age, sex, marital status, religion, occupation, or education (21,27). Furthermore, Cameroon reported a prevalence of 73.2%, significantly associated with age, socioeconomic status, alcohol consumption, family history, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Additionally, anemia, duodenal ulcer, and chronic gastritis were commonly observed in patients with H. pylori infection (28). Algeria documented a prevalence rate of 71.43% (29), while Ethiopia reported a prevalence of 88.9% among males and 82.8% among females (30). These African prevalence rates surpass those reported in other continents, with Europe (Germany) registering rates of 20–40% in 2018 (31), North America at 23.1% (32), Australia at 24.6% (33), and Asia at 48.8% (33).

In Somalia, a nation situated in the Horn of Africa, empirical data on H. pylori epidemiology has historically been scarce. While clinical recognition acknowledges the prevalence of H. pylori infection, the establishment of national prevalence rates and associated risk factors has been hindered by limited research output, a consequence of decades of socioeconomic disruption (34). However, recent years have seen a growing research focus on infectious diseases, with several studies investigating H. pylori prevalence and related factors in diverse Somali patient populations. The synthesis of emerging evidence offers an invaluable initial insight into the epidemiological landscape of this pivotal infection within Somalia, potentially shaping future research directions, policy formulations, and clinical practices.

To date, no comprehensive review has been published encompassing the prevalence of H. pylori in Somalia over time. Given the public health significance of H. pylori infection, even within populations exhibiting comparatively lower prevalence rates, such as Somalia, and considering the absence of existing reviews on H. pylori prevalence specific to Somalia, this scoping review aims to systematically identify and elucidate all studies reporting the prevalence of H. pylori in Somalia. In particular, this scoping review endeavors to delineate the characteristics of H. pylori prevalence studies within Somalia, including geographical locations, target populations, and diagnostic methodologies. Furthermore, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of prevalence estimates based on individual attributes such as population types, diagnostic categories, age groups, and gender, while also considering temporal dimensions.

The execution of this scoping review adhered to the methodology delineated by Arksey and O’Malley (35) as well as the guidance provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute, (36).

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate was conducted using the terms (“Helicobacter pylori” OR “H. pylori”) AND (prevalence OR epidemiology) AND Somalia. The search encompassed publications from inception to August 1st 2023, without limitations on the publication year, to ensure a thorough review of the available literature.

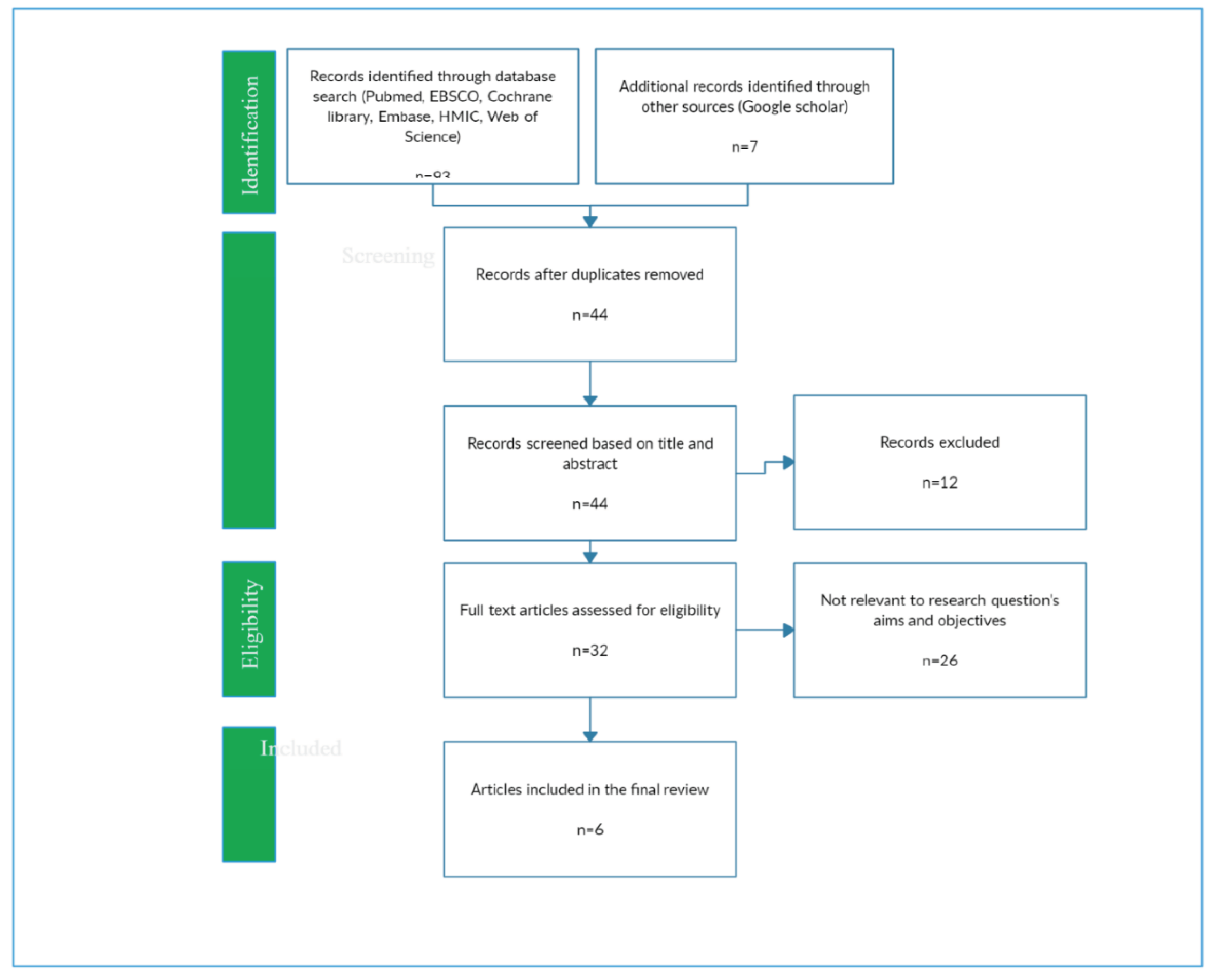

A total of 91 records surfaced from the database search. These records underwent a rigorous screening process conducted by two independent reviewers, encompassing the examination of titles, abstracts, and full-texts. The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: 1) Original research investigations, 2) Conducted within the geographical boundaries of Somalia, 3) Reporting H. pylori prevalence rates, and 4) Published during the defined timeframe from inception to August 1st 2023 Conversely, studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) Pertained to literature or systematic reviews, 2) Did not specifically focus on Somalia, 3) Did not report H. pylori prevalence.

A meticulously tailored spreadsheet was employed for the systematic extraction of data from the selected studies. The information extracted encompassed various critical aspects, including the names of the author(s), publication year, study location, study design, composition of the sample population, sample size, participant demographics, the method employed for H. pylori diagnosis, the prevalence rates reported, and the identification of factors associated with H. pylori infection.

The initial database search yielded a total of 91 articles. However, following a meticulous review process, a substantial portion of these records (85 in total) were deemed ineligible for inclusion. The grounds for exclusion varied and encompassed topics unrelated to H. pylori prevalence, studies conducted beyond the territorial confines of Somalia, and systematic reviews. Ultimately, a total of 6 studies aligned with the defined inclusion criteria and were thus incorporated into this scoping review (

Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The key characteristics of the 6 included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of the 6 Included Studies

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of the 6 Included Studies

| Study |

Year |

Location |

Study Design |

Sample Size |

Population |

Diagnostic Method |

| 1 |

2022 |

Kalkaal Hospital |

Hospital-based cross-sectional |

261 |

Patients visiting hospital |

Not specified |

| 2 |

2023 |

Aden Ade Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

Not specified |

Patients visiting hospital |

Not specified |

| 3 |

2022 |

Aden Abdulle Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

323 |

Outpatients |

Stool sample |

| 4 |

2022 |

Shaafi Hospital |

Descriptive cross-sectional |

95 |

Patients at Shaafi hospital |

Not specified |

| 5 |

2023 |

Somali Sudanese Specialized Hospital |

Descriptive cross-sectional |

1009 |

Gastrointestinal symptom patients at SSSH |

Stool sample |

| 6 |

2022 |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

The investigations were all observational studies focused on Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence in Mogadishu, Somalia. Two studies used a cross-sectional framework [

37,

38], while two others used a descriptive cross-sectional methodology [

39,

40]. One study explicitly mentioned being hospital-based [

41], and another did not specify its classification [

42].

The sample sizes varied significantly, ranging from 95 participants to 1009 individuals. This variation affects the statistical robustness and precision of the studies in identifying H. pylori prevalence trends.

The study population included both ambulatory outpatients and bedridden inpatients with various gastrointestinal symptoms. This diverse patient demographic reflects the wide range of symptomatic presentations associated with H. pylori infection.

Participants in the studies spanned different age groups, from pediatric to elderly adults. This inclusive approach allows for a thorough examination of potential variations in H. pylori prevalence across age groups, revealing age-related trends.

While three studies used laboratory-based stool sample analysis for H. pylori diagnosis, the diagnostic methodologies used in the remaining three studies were not disclosed. This lack of transparency in diagnostic methods should be considered when interpreting and comparing the findings of these particular investigations.

Table 2.

Summary of H. pylori Prevalence Rates in the 6 Included Studies

Table 2.

Summary of H. pylori Prevalence Rates in the 6 Included Studies

| Study |

Location |

Sample Size |

Population |

Prevalence Rate |

| 1 |

Kalkaal Hospital, Mogadishu |

261 |

Patients visiting hospital |

Not reported |

| 2 |

Aden Ade Hospital, Mogadishu |

Not specified |

Patients visiting hospital |

32.4% |

| 3 |

Aden Abdulle Hospital, Mogadishu |

323 |

Outpatients |

42.7% |

| 4 |

Shaafi Hospital, Mogadishu |

95 |

Patients at Shaafi hospital |

Not reported |

| 5 |

Somali Sudanese Specialized Hospital, Mogadishu |

1009 |

Gastrointestinal symptom patients at SSSH |

44.8% |

| 6 |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not reported |

The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection within the examined studies exhibited a notable breadth, spanning from the lower bound of 32.4% [

12] to the upper threshold of 56.5% [

40], thus encapsulating a substantial range of prevalence rates. A prevailing trend across the majority of these investigations manifested in the manifestation of prevalence rates surpassing the 40% benchmark.

Of particular significance is the hospital-based inquiry conducted at Kalkaal Hospital, which unveiled a noteworthy observation. In this study, it was discerned that the prevalence of gastritis among symptomatic patients attained an astonishingly elevated rate of 100%. It is imperative to acknowledge, however, that the direct measurement of H. pylori itself was not undertaken within this specific investigation [

15].

An exploration into temporal fluctuations in prevalence rates was a distinctive facet examined within a singular study. Within this investigation, a meticulous assessment of monthly variations was conducted, revealing a substantial oscillation in H. pylori prevalence, with figures ranging from 26.9% to the apex of 56.5% [

40]. This dynamic temporal pattern underscores the potential for fluctuations in H. pylori prevalence, adding a layer of complexity to the epidemiological dynamics of this infection.

Table 3.

Variability in Factors Analyzed for Association with H. pylori Infection Across the 6 Studies

Table 3.

Variability in Factors Analyzed for Association with H. pylori Infection Across the 6 Studies

| Study |

Factors Analyzed |

| 1 |

Gender, age, occupation, education, marital status |

| 2 |

Age, family history of gastritis, eating habits, lifestyle factors |

| 3 |

Age, gender, residence, smoking, chewing khat |

| 4 |

Gastritis symptoms |

| 5 |

Month of study |

| 6 |

Not reported |

The exploration of associations between various factors and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection unveiled intriguing patterns across the examined studies.

Gastritis symptoms, a salient clinical feature, came under scrutiny within three distinct investigations. Remarkably, all three studies discerned affirmative associations, signifying a positive correlation between the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and H. pylori infection [37, 39, 40].

The influence of gender on H. pylori prevalence was a focal point of investigation in five studies. Among these, two studies unearthed a statistically significant predilection towards higher prevalence rates among the female demographic [39, 41]. In contrast, the remaining three studies found no substantive gender-based disparities in H. pylori prevalence [37, 38, 40].

The potential nexus between age and H. pylori prevalence was explored within three distinct studies. However, none of these investigations yielded findings suggestive of a significant relationship between age and H. pylori prevalence [37, 38, 40].

Explorations into demographic attributes such as residence, as well as socioeconomic determinants including education and occupation, were subjected to scrutiny across select studies. Notably, the empirical findings failed to establish any discernible associations between these factors and H. pylori infection in the limited studies that undertook their analysis [

37,

39].

Lifestyle factors, encompassing dietary habits, smoking, khat chewing, and others, were probed for their potential linkages with H. pylori infection within select studies. Yet, the empirical evidence generated within these investigations collectively did not reveal any substantive evidence to assert the significance of these lifestyle attributes as substantial risk factors for H. pylori infection [37, 38].

Family history and the presence of comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), were examined individually within one study each. These investigations unveiled positive associations, suggesting that individuals with such medical histories may indeed exhibit a heightened vulnerability to H. pylori infection [38, 39].

The primary objective of this scoping review was to delineate the landscape of studies documenting the prevalence of H. pylori in Somalia, focusing on key study characteristics such as study design, geographic region, population attributes, and diagnostic methodologies.

Additionally, this review aimed to provide a summary of the estimated prevalence within these studies, considering individual characteristics and temporal dimensions. Consequently, this review has succeeded in assembling the most comprehensive repository of H. pylori prevalence data within the Somali context to date.

The synthesis of research conducted over the past two years pertaining to the prevalence of H. pylori infection and its associated factors in Somalia has yielded a multifaceted portrait. The six studies incorporated in this review have reported prevalence rates spanning a spectrum from 32.4% to 56.5%, primarily within symptomatic adult outpatient populations. Notably, one study exhibited significant monthly variation in prevalence (40). Robust and consistent associations were observed with gastritis symptoms and female gender, aligning with the well-established pathophysiological link between chronic gastric inflammation and H. pylori infection. Conversely, age, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle habits failed to manifest clear associations with prevalence. Data pertaining to family history and comorbidities were scarce, impeding comprehensive analysis.

The wide-ranging prevalence estimates across the included studies can be attributed, in part, to the variability in patient populations across different hospital settings. Nevertheless, the uniformity in the high burden of H. pylori infection among these studies mirrors patterns observed not only across Africa but also in other developing regions (13, 14, 15). The observed increase in infection over time within the Somali Sudanese Specialized Hospital study (40) may reflect cyclic acquisition patterns or the presence of sampling bias.

The robust associations between the presence of gastritis symptoms and H. pylori positivity underscore the fundamental pathophysiological mechanisms by which the bacterium induces chronic gastric inflammation. The higher susceptibility of females to H. pylori infection, though less comprehensively understood, is a consistently reported global phenomenon (42). The lack of clear age-related associations in this review may be attributed to the relatively young adult samples under scrutiny (43). Notably, the absence of discernible links between socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors concurs with prior reports, suggesting that these variables do not exert substantial influence on H. pylori prevalence, in contrast to their impact on gastrointestinal sequelae such as peptic ulcers or cancer (44). It is imperative to acknowledge that the limited availability of evidence within the Somali population precludes definitive conclusions regarding the pertinent risk factors.

In light of the elevated prevalence rates, it is prudent to consider the implementation of screening and treatment protocols for H. pylori in Somalia, particularly among individuals presenting with gastritis and ulcers. However, it is crucial to recognize that all included studies in this review relied on hospital-based sampling, thereby constraining the generalizability of their findings to the broader population. The need for comprehensive population-level data is evident, as the small sample sizes in most studies may not accurately reflect the true prevalence in the Somali populace. Additionally, some studies inadequately described their H. pylori diagnostic methods, potentially introducing ambiguity into the interpretation of their results.

The limited overlap in the risk factors assessed across studies further restricts the potential for pooled analysis. Moreover, the concentration of all studies within Mogadishu city limits their representativeness at the national level. The utilization of cross-sectional designs within these studies limits the ability to establish temporal relationships. Finally, there may exist a potential publication bias toward studies reporting positive findings, warranting cautious interpretation of the aggregated results.

All included studies relied on hospital-based sampling, limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. The relatively small sample sizes in most studies may not accurately reflect the true prevalence of H. pylori in the Somali population. Some studies did not provide clear descriptions of their H. pylori diagnostic methods, potentially introducing ambiguity into the interpretation of their results. The limited overlap in the assessment of risk factors across studies restricts the potential for pooled analysis and comprehensive risk assessment. All studies were confined to Mogadishu city, which hampers their ability to represent the national prevalence. The utilization of cross-sectional designs within these studies restricts the ability to establish temporal relationships. There may be a potential publication bias toward studies reporting positive findings, necessitating cautious interpretation of the synthesized results.

Author Contributions

Mohamed Jayte conducted all aspects of this study, including conceptualization, study design, data collection, statistical analysis, literature review, initial manuscript drafting, data interpretation, manuscript revisions, and final version approval.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding, as it was independently conducted by the authors. We believe that this absence of external influence ensures the impartiality and credibility of our research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in strict adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were not deemed necessary for this research, as it involves a review of previously published studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this research are accessible through the previously published studies.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests that could potentially influence the outcome or interpretation of the findings presented in this research study.

Accessibility of Research Data: For those seeking access to the datasets used and analyzed in this study, we encourage you to contact the corresponding author of this research and submit a reasonable request. We are committed to promoting transparency and the advancement of knowledge in our field.

Ethics Considerations: Not applicable.

References

- Kusters, Van Vliet & Kuipers (2006) Kusters JG, Van Vliet AHM, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al. (2017) Jiang J, Chen Y, Shi J, Song C, Zhang J, Wang K. Population attributable burden of Helicobacter pylori-related gastric cancer, coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke in China. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2017, 36, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. (2017) Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 112, 212–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al. (2016) Ford AC, Gurusamy KS, Delaney B, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease in Helicobacter pylori-positive people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;4:CD003840. [CrossRef]

- Shiotani, Cen & Graham (2013) Shiotani A, Cen P, Graham DY. Eradication of gastric cancer is now both possible and practical. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2013;23(6, Part B):492–501. [CrossRef]

- et al. (2020) De Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2020, 8, e180–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al. (2020) De Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2020, 8, e180–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al. (2014) Stewart BWKP, Khanduri P, McCord C, Ohene-Yeboah M, Uranues S, Vega Rivera F, Mock C. Global disease burden of conditions requiring emergency surgery. Journal of British Surgery 2014, 101, e9–e22. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, Van Vliet & Kuipers (2006) Kusters JG, Van Vliet AHM, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- et al. (2002) Nomura AMY, Pérez-Pérez GI, Lee J, Stemmermann G, Blaser MJ. Relation between Helicobacter pylori cagA status and risk of peptic ulcer disease. American Journal of Epidemiology 2002, 155, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. (2017) Hooi JK, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MM, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VW, Wu JC, Chan FK. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. (2014) Peleteiro B, Bastos A, Ferro A, Lunet N. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection worldwide: a systematic review of studies with national coverage. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2014, 59, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Umar, A.B.; Borodo, M.M. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroduodenal diseases in Kano, Nigeria. Afr J Med Health Sci. 2018, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etukudo, O.M.; Ikpeme, E.E.; Ekanem, E.E. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among children seen in a tertiary hospital in Uyo, Southern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Odigie, A.O.; Adewole, A.J.; Ekwunwe, A.A. Prevalence and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection among treatment naive dyspeptic adults in University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria. Afr J Clin a Exp Microbiol. 2020, 21, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, O.M.; Chukwuma, G.O.; Manafa, P.O.; Akulue, J.C.; Jeremiah, Z.A. Prevalence and possible risk factors for Helicobacter pylori seropositivity among peptic ulcerative individuals in Nnewi Nigeria. Biomed Res J. 2020, 4, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Daniyan Olapeju, W.; Ibe Chidozie, C.; Ezeonu Thecla, C.; Anyanwu Onyinye, U.; Ezeanosike Obumneme, B.; Omeje Kenneth, N. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori among children in South East Nigeria. J Gastroentrol Hepatol Res. 2020, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Adedoyin JJ, David I. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among children selected hospitals in Keffi, Nigeria. Adv Pub Health Com Trop Med. 2020. Epub ahead of print. APCTM-120. [CrossRef]

- Ntagirabiri R, Harerimana S, Makuraza F, Ndirahisha E, Kaze H, Moibeni A. Helicobacter pylori in Burundi: first assessment of endoscopic prevalence and eradication. J Afr Hépatol Gastroentérol. 2014, 8, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker TD, Karemera M, Ngabonziza F, Kyamanywa P. Helicobacter pylori status and associated gastroscopic diagnoses in a tertiary hospital endoscopy population in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:305–7. [CrossRef]

- Lawson-Ananissoh LM, Bouglouga O, Bagny A, El-Hadj Yakoubou R, Kaaga L, Redah D. Epidemiological profile of peptic ulcers at the Lomé campus hospital and university center (Togo). J Afr Hépatol Gastroentérol. 2015, 9, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossali F, Deby G, Ahoui-Apendi CR, Ndolo D, Ndziessi G, Atipo-Ibara BI, Study of the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in the cities of pointe-noire and Bbrazzaville in 2015. Ann Univ M Ngouabi. 2017, 17, 1–9.

- Sokpon M, Salihoun M, Lahlou L, Acharki M, Razine R, Kabbaj N. Predictors of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection in chronic gastritis: about a Moroccan study. J Afr Hépatol Gastroentérol. 2016, 10, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Awuku YA, Simpong DL, Alhassan IK, Tuoyire DA, Afaa T, Adu P. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among children living in a rural setting in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal YS, Ghobrial CM, Labib JR, Abou-Zekri ME. Helicobacter pylori among symptomatic Egyptian children: prevalence, risk factors, and effect on growth. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2019;94:17. [CrossRef]

- Kpossou AR, Kouwakanou B, Séidou F, Alassane KS, Vignon RK, Sokpon CNM, Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric preneoplastic lesions in patients admitted for upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy in Cotonou (Benin Republic). Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 11, 208–213.

- Bertrant EB, Epesse SFEB, Stephane MB, Clementine F, Roger K, Brigitte KJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and relevant endoscopic features among patients with gastro-duodenal disorders. a three years cross sectional study in the Littoral region of Cameroon. Eur J Sci Res. 2020, 15, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kasmi H, Doukani K, Ali A, Tabak S, Bouhenni H. Epidemiological profile of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with digestive symptoms in Algeria. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asfaw T. Prevalence and emergence of drug resistance in Helicobacter pylori: review. Int Res J Microbial. 2018, 7, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach W, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018, 115, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja F, Kreiger N, Sullivan T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Ontario, prevalence and risk factors. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.H.; Phan, T.T.B.; Nguyen, V.B.; Hoang, T.T.H.; Le, T.L.A.; Nguyen, T.T.M. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Muong children in Vietnam. Ann Clin Lab Res. 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Haimanot, R.T. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries: the burden for how long? BMJ Glob Health 2020, 5, e002019. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar Hussein, A. Prevalence and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori Infection in adults attending medical outpatient unit at Aden Abdulle Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia (Doctoral dissertation). 2022.

- Ramla Nour Mohamud. A cross-sectional survey of gastritis and associated risk factors among patients visiting Aden adde hospital Mogadishu. Accord University Health Journal 2023;Vol,1. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hassan Mohamed, 2022, research gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361337795_Knowledge_Attitude_and_Practice_on_Gastritis_among_Patients_with_Gastritis_in_Shaafi_Hospital_Mogadishu-_Somalia.

- Ebar, M.H.O.; Ahmed, M.O.H.M. Frequency of H. pylori Infection among Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms Attending Somali Sudanese Specialized Hospital (SSSH), Mogadishu, Somalia. Asian journal of medicine and health 2023, 21, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Mohamed, S.A.; Kimutai, T.K. Risk Factors of Gastritis and its Prevalence Among Patients Visiting Kalkaal Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 2022, 7, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi, L.H.; Zagari, R.M.; Bazzoli, F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miernyk, K.; Morris, J.; Bruden, D.; McMahon, B.; Hurlburt, D.; Sacco, F.; et al. Characterization of Helicobacter pylori prevalence and risk factors among Alaskans. Helicobacter 2011, 16, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.Y.; Malaty, H.M.; Evans, D.G.; Evans, D.J.; Klein, P.D.; Adam, E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States: effect of age, race, and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology 1991, 100, 1495–14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).