Preprint

Article

Assessment of Knowledge and Attitude of Reproductive Age Women towards Cervical Cancer Prevention in Selected Tertiary Institutions in Osun State, Nigeria

Altmetrics

Downloads

201

Views

157

Comments

1

Submitted:

16 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Cervical cancer is the second most frequent cancer among women worldwide between 14 and 49 years of age including Nigeria. Figures have greatly reduced in developed countries after the introduction and implementation of effective screening and vaccination programs which is greatly undeveloped and inefficient in Nigeria and other developing countries at large. OBJECTIVES: The study assessed the knowledge and attitude of reproductive age women towards cervical cancer prevention in selected tertiary institutions in Osun State. METHODOLOGY: The study was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out among reproductive age women in selected tertiary institutions in Osun State, Nigeria. A probability based multistage sampling technique was adopted as the sampling technique for the study. Data was collected using a semi-structured, self-administered and interviewer guided questionnaire. RESULTS: Age of respondents was 25.305±8.195. 313(79.0%) of the total respondents were Christians, and 83(21.0%) of the respondents were Muslims. For the overall knowledge score, only 52.0% of the respondents had good knowledge while 48.0% of the respondents had poor knowledge. 52.0% exhibited negative attitude towards cervical cancer prevention while 48% exhibited positive attitude towards cervical cancer prevention. Only 23% of the respondents had taken part in screening and vaccination towards cervical cancer prevention while 77% of the respondents had not. CONCLUSION: The knowledge of reproductive age women towards cervical cancer prevention was above average while their attitude towards cervical cancer prevention was low. This issue could be addressed by increasing the awareness of the effects of cervical cancer among reproductive age women in the country.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Public Health and Health Services

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer (CC) is a cancer of the cervix, the cervix is a female reproductive organ connecting the uterus and the vagina. The human papilloma virus (HPV) is the primary cause of cervical cancer. According to ASCO (2020)1, cervical cancer begins on the cells on the surface of the cervix once infected with the human papilloma virus. Long-term infection of HPV on the cervix may result in cancer, resulting in a lump or tumor on the cervix. Tumors can be malignant or non-malignant. A malignant tumor has the ability to spread to other body parts, whereas a benign tumor, also known as a non-malignant tumor, is one that will not spread (ASCO, 2020)1. The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a sexually transmitted infection that can be acquired through vaginal, oral, or anal sex or through body-to-body contact with an infected person during sexual intercourse. Most people infected with HPV do not develop cancer, but the infection can raise the risk, especially in people with compromised immune systems. Cervical cancer is the most common genital cancer in women and one of the leading causes of death. Fortunately, this cancer can be avoided by getting vaccinated before starting sexual activities and getting screened for premalignant lesions starting at the age of 21, but in developing countries, these services are scarce and infrequently used.2

In addition, Cervical Cancer has been identified as the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in developing countries.3 Cervical Cancer is the second most common disease in women worldwide, with an estimated 528,000 new cases and 266,000 deaths per year.4 in 2008, 530,000 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed worldwide, with 275,000 fatalities. Surprisingly, the majority of these deaths happened in developing countries. In the same year, the WHO African region reported an additional 75,000 cases.5 More so, an estimated 10,000 new instances of cervical cancer are recorded in Nigeria, with 8000 female mortality each year according to.6 Women with a weakened immune system, such as those living with HIV, have a higher rate of HPV infection than women who do not have HIV, according to previous research.7 This is because the immune system isn’t fit enough to ward of the effect of HPV as it’s already subjected to other viruses, hence the need to take the preventive practices of cervical cancer (CC) with utmost seriousness.

The ravaging situation of cervical cancer in Nigeria owes its high prevalence and mortality rate to the combination of the ignorance on preventive measures both primary and secondary, and unwillingness to use the preventive measures even when they are aware of it. This condition is crucial since there is a scarcity of infrastructure for effective treatment of invasive cervical cancer, especially when it is discovered late in the disease's progression. The majority of malignancies in Nigeria are discovered late in their progression, with a low chance of survival.8 the incidence of cervical cancer is quite low in prosperous countries. The situation in developing countries, on the other hand, is considerably different. While the former is becoming less prevalent, the latter is gaining popularity.9 this is most likely due to a low percentage of women getting vaccinated, Pap smears, poor knowledge, negative attitude and lack of awareness among women.10

Pap smear screening (A screening for cervical cancer) should begin at age 21 according to Saslow et al., (2012).11 As a result, regardless of the age of sexual initiation or other behavior-related risk factors, women below 21years should not be checked. Furthermore, according to WHO (2014)12, screening for cervical cancer among women between 30 and 49 years , for at least once, will decrease mortality rate from cervical cancer.

Human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted virus, has been identified as the causative agent. The new cervical cancer prevention strategy focuses on immunizing against this HPV infection prior to the first sexual exposure as a type of primary prevention, or screening for evidence of pre-invasive cervix lesions as a type of secondary prevention.13 meanwhile, these services are not part of the national immunization schedule. The prices of getting vaccinated against human papilloma virus and getting screened for premalignant lesions are not pocket friendly due to the current economy. Hence our reason to conduct this study among reproductive age women to create awareness, and increase their knowledge on HPV and its risk so they can abstain from premarital sexual activities prior vaccination, and also to go for screening three to four times between the age of 21-49 if they’ve been exposed to sexual activities so as to lower the risk of CC. Furthermore, to implore the government to put the lives of Nigerian women into consideration by birthing these services in the national immunization schedule.

METHODS

Study design, and study setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study was employed to carry out the study. Study setting; the study was conducted among female undergraduates in selected tertiary institutions in Osun State. The institutions were selected using a simple random sampling technique by balloting. The selected institutions are: Adeleke University Ede Osun state, Redeemer’s University Ede Osun State, and Osun State University, Oshogbo Osun State.

Target population

The target population included female undergraduate attending various tertiary institutions in Osun State. However, the assessed population included Osun State University (Oshogbo Chapter), Redeemers University and Adeleke University Ede, Osun State.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

Female undergraduates between the ages of 15-49 who were around during the period of conducting this study. While potential respondents who declined consent to participate in the study were excluded.

Definition of operational terms

- KNOWLEDGE: The act of being familiar or having understanding of CC prevention

- ATTITUDE: The act of expressing ones understanding in the prevention of CC

- CERVICAL CANCER: Cervical cancer affects the human cervix

- CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING: Cervical cancer screening is a screening that detect unusual changes in the cervix.

- HUMAN PAPILLOMA VIRUS (HPV): Human papilloma virus is the primary cause of cervical cancer.

Sample technique and sample size determination

A probability based multistage sampling technique was adopted to select the institutions and the respondents.

Stage 1: Selection of institutions

Three (3) tertiary institutions were chosen by balloting, a simple random sampling technique to give institutions, both government owned and private owned in Osun State an equal chance of being chosen.

Stage 2: Selection of Faculties

Simple random sampling technique was adopted for the selection of faculties in each institution to give every faculty an equal chance of being chosen and two faculties from each institutions were chosen by balloting.

Stage 3: Distribution of Questionnaires

Questionnaires were distributed in the selected institutions in the respective faculties that were selected by balloting using proportionate sampling.

The sample size for this study was calculated using Taro Yamane (1967) formula to obtain the sufficient sample size. This sample size was used because we dealt with a finite population. The formula applied is given as

n = N / (1 + N (e) 2)

Where n = Sample size, N = Total population under study, e = margin error and 1 = adjusted constant. Numbers were substituted for variables and a sample size of 377 was gotten 10% attrition rate was added and the total sample size was 415.

Instrument for data collection

The study adopted a primary source of data collection. The instrument was a Semi-structured questionnaire, designed to include both open-ended and close-ended questions. The questionnaire was categorized into four sections with 47 total variables.

Data analysis

The information obtained were collated, examined for completion and was imputed into IBM SPSS (statistical product and service solution) version 25.0 for analysis. Percentages, frequencies, tables and charts were used to analyse and present data related to objectives and socio-demographic characteristics. To assess the level of knowledge, knowledge questions were scaled and scored and categorized to the best midline such that 0-11(first half) was coded as poor knowledge and 12-23 (second half) as good knowledge, to assess the level of attitude, attitude questions were scaled and scored and categorized to the best midline such that 0-5(first half) was coded as negative attitude and 6-11(second half) as positive attitude. All right responses were coded as 1 and all wrong responses were coded as 0. Chi square was used to test the association between the knowledge and practice of cervical cancer prevention as well as attitude and practice of cervical cancer prevention among reproductive age women in the selected institutions in Osun state. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Decision rule is that at p value less or equal to 0.05, hypothesis was considered statistically significant and greater than 0.05 was considered statistically not significant.

Validity and reliability of instrument

The question undergone face and content validity by our research supervisor, who scrutinized the items and ensured they captured the true picture of variables under the study. Her comment and observation were used to revisit the questionnaire before the final draft.

Reliability was determined through a pre-test carried out among 42 female students in federal polytechnic Ede, Osun State.

Reliability test for level of knowledge variables was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha with intra-class coefficient value of 0.72.

Reliability test for level of attitude variables was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha with intra-class coefficient value of 0.76

RESULTS

Table 1 presents distribution of respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. The mean age of respondents was 25.305±8.195. 313(79.0%) of the total respondents were Christians, and 83(21.0%) of the respondents were Muslims. On ethnicity, (82.1%) were Yoruba, 11.9% were Igbo and 3.2% were Hausa 2.77% belonged to other tribes. On mode of study, most (97.5%) were full time students, while 2.5% were into part time programme. On level, almost half (48.5%) of the respondents were from 100 level, 12.1% were from 200 level, 11.0% were from 300 level, 24.2% were from 400 level, while 4.0% were from 500 level. On marital status, majority (93.9%) were single, while rest (6.1%) were married.

Table 1.

Distribution of Respondents by Socio-Demographic Characteristics (N=396).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 16-20 | 276 | 69.7 |

| 21-25 | 103 | 26.1 |

| 26-30 | 17 | 4.3 |

| Mean age (years) | 25.305±8.195 | |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 313 | 79.0 |

| Islam | 83 | 21.0 |

|

Ethnicity |

||

| Yoruba | 325 | 82.1 |

| Igbo | 47 | 11.9 |

| Hausa | 13 | 3.28 |

| Others | 11 | 2.77 |

|

Mode of study |

||

| Full Time | 386 | 97.5 |

| Part Time | 10 | 2.5 |

| Total | 396 | 100 |

|

Level 100 |

192 |

48.5 |

| 200 | 48 | 12.1 |

| 300 | 44 | 11.1 |

| 400 | 96 | 24.2 |

| 500 | 16 | 4.0 |

|

Marital Status |

||

| Single | 372 | 93.9 |

| Married | 24 | 6.1 |

| Total | 396 | 100.0 |

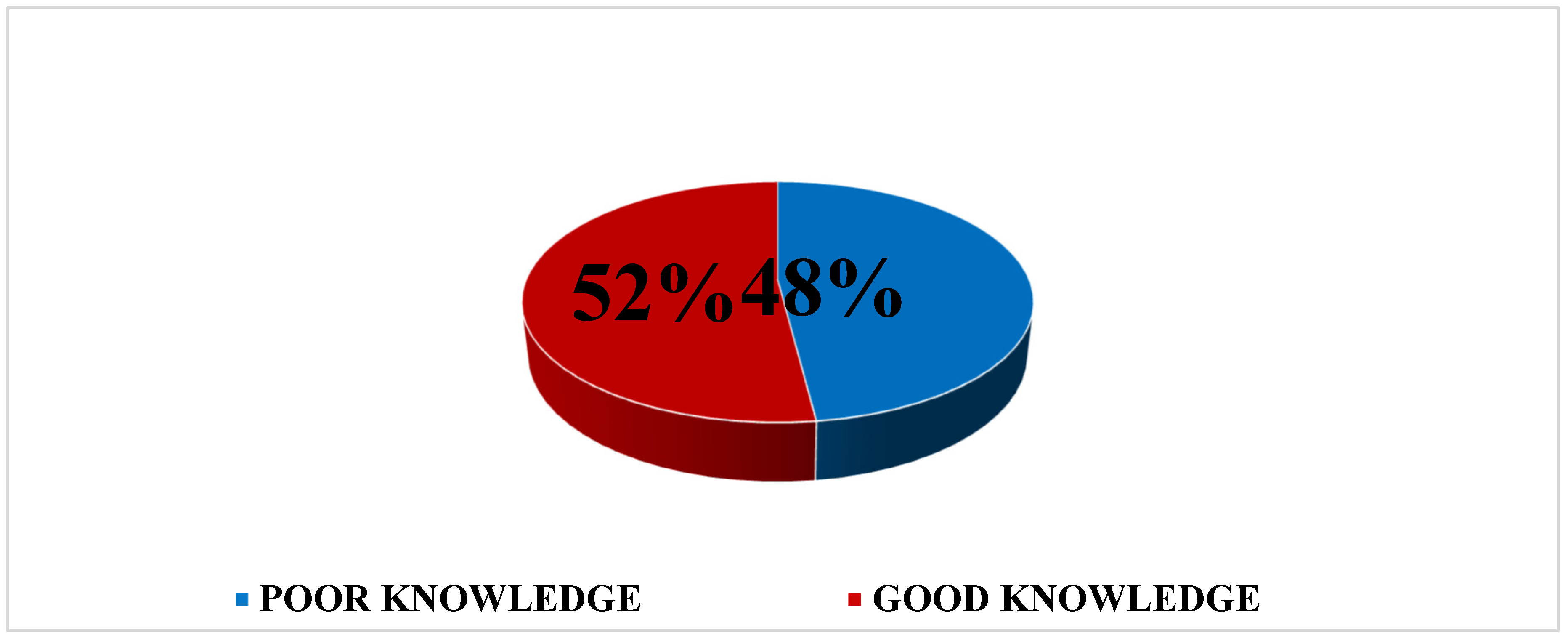

Figure 1.

Knowledge score of cervical cancer prevention.

Table 2 presents the knowledge of reproductive age women on Cervical Cancer Prevention. Overall Results revealed that 52.0% had good knowledge, while 48.0% had poor knowledge.

Table 2.

Knowledge of Respondents on Cervical Cancer Prevention (N=396).

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you heard of human papilloma virus | ||

| No | 152 | 38.4 |

| Yes | 244 | 61.6 |

|

Which of the following is your source of information |

||

| School | 17 | 4.29 |

| Media | 72 | 18.2 |

| Friends | 59 | 15.0 |

| Family members | 52 | 13.1 |

| Church members | 49 | 12.3 |

| Health worker | 125 | 31.5 |

| Others | 22 | 5.55 |

|

Is HPV a virus? |

||

| No | 190 | 48.0 |

| Yes | 206 | 52.0 |

|

How do you think HPV is transmitted |

||

| Skin to skin contact | 120 | 30.3 |

| Coughing and sneezing | 89 | 22.4 |

| Contact with body fluids | 50 | 12.6 |

| Toilet seat | 68 | 17.1 |

| Self-inoculation (Orally) | 51 | 12.9 |

| I don’t know | 18 | 4.7 |

|

Which of the following health issues are related to HPV |

||

| Cervical Cancer | 112 | 28.3 |

| Genital warts | 98 | 24.7 |

| Penile cancer | 52 | 13.1 |

| Breast cancer | 47 | 11.9 |

| Vulva cancer | 39 | 9.9 |

| I don’t know | 29 | 7.3 |

| None | 19 | 4.8 |

|

Do you know that human papilloma virus can be prevented | ||

| No | 294 | 74.2 |

| Yes | 102 | 25.8 |

|

Have you heard of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccines | ||

| No | 198 | 50.0 |

| Yes | 198 | 50.0 |

|

Have you heard of cervical cancer |

||

| No | 66 | 16.7 |

| Yes | 330 | 83.3 |

|

Have you heard of cervical cancer screening test |

||

| No | 114 | 28.8 |

| Yes | 282 | 71.2 |

|

What is cervical cancer screening test called |

||

| Pap smear | 242 | 61.1 |

| HPV testing | 82 | 20.7 |

| Visual examination | 60 | 15.2 |

| I don’t know | 12 | 3.02 |

|

Do you know that the intake of HPV vaccine could lower the risk of cervical cancer | ||

| No | 176 | 44.4 |

| Yes |

220 | 55.6 |

| Intake of HPV vaccines before the start of sexual activities can prevent the onset of human papilloma virus | ||

| No | 272 | 68.7 |

| Yes |

124 | 31.3 |

| Is cervical cancer a preventable disease | ||

| No | 73 | 18.4 |

| Yes | 323 | 81.6 |

|

Do you know that early screening uptake can detect an abnormal growth in the cervix | ||

| No | 136 | 34.3 |

| Yes | 260 | 65.7 |

|

STD is a risk to cervical cancer |

||

| No | 73 | 18.4 |

| Yes | 323 | 81.6 |

|

Having sex with multiple persons can be a risk to cervical cancer | ||

| No | 71 | 17.9 |

| Yes | 325 | 82.1 |

|

Having sex with a person with multiple sexual partners can also be a risk to cervical cancer | ||

| No | 182 | 46.0 |

| Yes | 214 | 54.0 |

|

Smoking is a risk to cervical cancer |

||

| No | 241 | 60.9 |

| Yes | 155 | 39.1 |

|

Oral contraceptives can pose a risk to cervical cancer |

||

| No | 180 | 45.5 |

| Yes | 216 | 54.5 |

|

Do you know that genetic history of cervical cancer can increase a person’s risk of cervical cancer | ||

| No | 144 | 36.4 |

| Yes | 252 | 63.6 |

|

Cervical cancer test is only for sick persons |

||

| No | 277 | 70.0 |

| Yes | 119 | 30.0 |

|

How many times should a woman undergo cervical cancer screening | ||

| Once | 110 | 27.8 |

| Twice | 4 | 1.0 |

| Thrice | 28 | 7.1 |

| four times | 231 | 58.3 |

| I don't know | 23 | 5.8 |

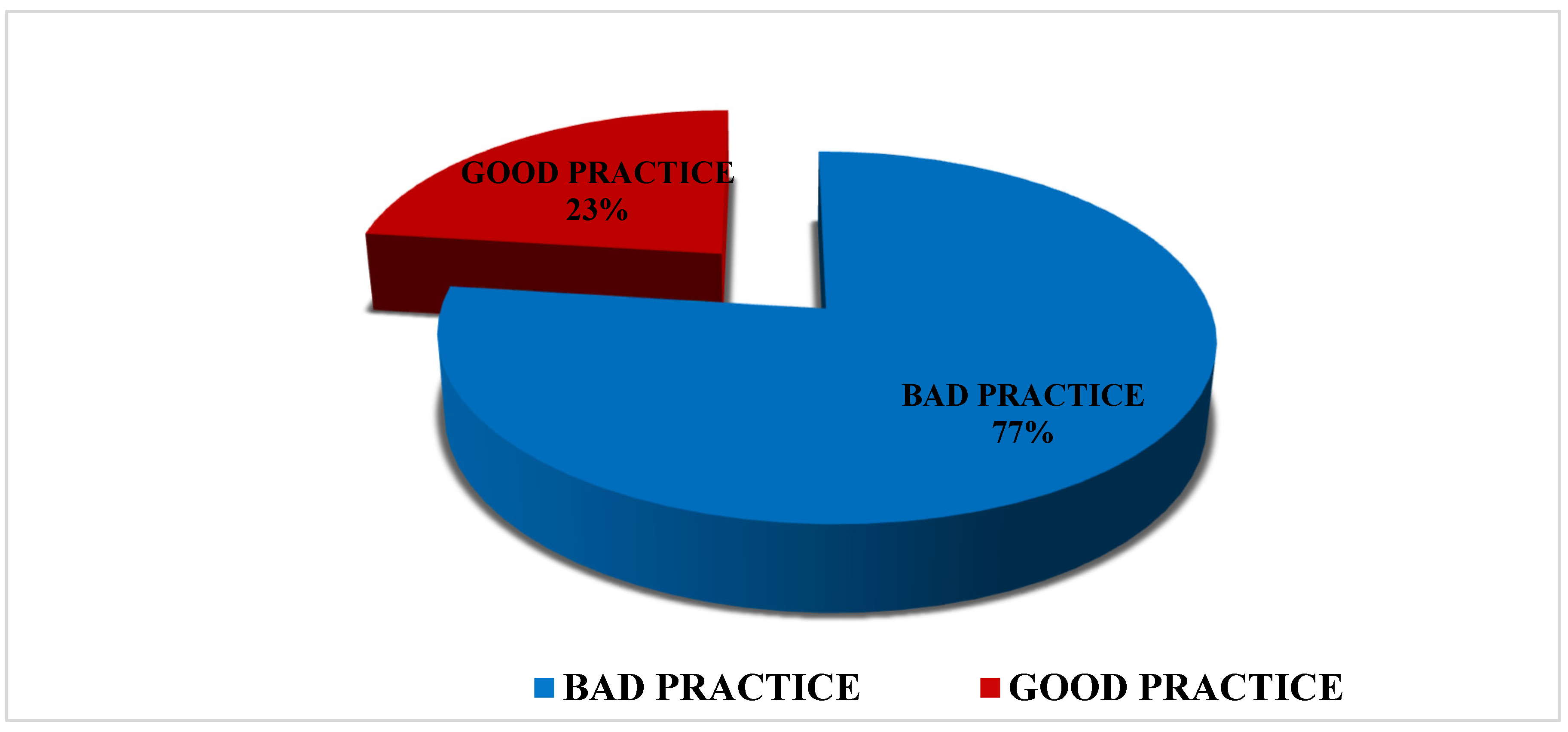

Figure 3.

Overall Practice Score of Cervical Cancer Prevention among Reproductive Age Women.

Women

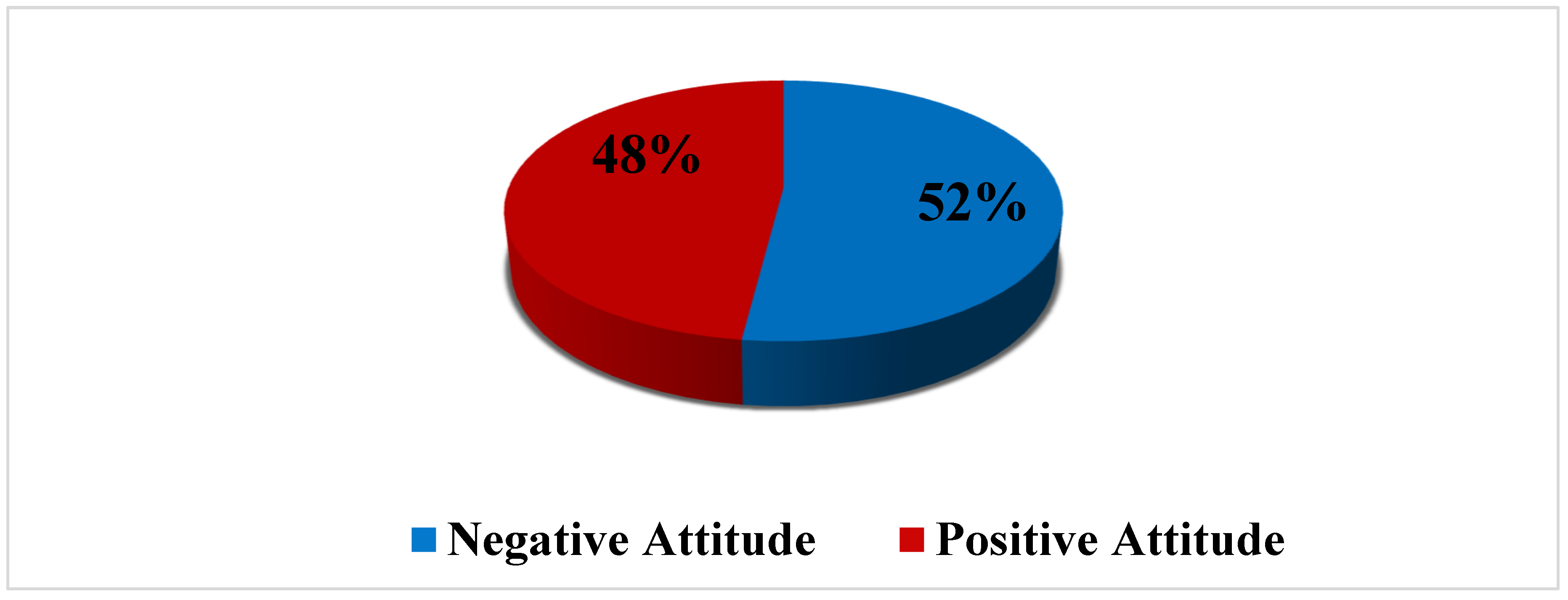

Table 3 presents the attitude of reproductive age women towards cervical cancer prevention. Overall Results revealed that, 52.0% had negative attitude, while 48.0% had positive attitude towards cervical cancer prevention.

Figure 3 presents the practice of reproductive age women towards cervical cancer prevention. Results revealed that, majority of the respondents demonstrated (77.0%) bad practice, while only 23.0% demonstrated good practice.

Table 4 showed that there is no significant association between knowledge and Practices of cervical cancer screening and vaccine intake towards cervical cancer prevention (χ2= 2.537a; p-value= .121; df =1). This implies that the knowledge demonstrated by the respondents do not have effect on the practice of cervical cancer prevention.

Table 5 showed that there is no significant association between attitude and Practices of cervical cancer prevention (χ2= .025a; p-value= .905; df =1). This result implies that, attitude is not a predictor as regards cervical cancer prevention.

DISCUSSION

Globally, adequate awareness have been found to be a tool for increase in preventive practices. The study revealed that, only about half (52.0%) of the respondent have adequate knowledge on Cervical Cancer prevention. This denotes that, a significant part (48%) of the respondents lack adequate knowledge of cervical cancer. This is in line with the some studies that have been conducted. Adebayo et al., 202114 reported 60.6% of antenatal attendees in Ibadan, south west Nigeria had good knowledge on cervical cancer. Likewise, a study conducted by Ekwonwa et al., (2017)15 among women of reproductive age in Ede South local government area in Osun State revealed that most of the respondents have good knowledge (72.8%) on cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening but in disparity with Ogbonna (2017)16, who held that less than half of his respondents had good knowledge on cervical cancer screening while had poor knowledge on cervical cancer screening (38% and 62% respectively).

Most of the respondents knew that cervical cancer screening test and that intake of HPV vaccine could lower the risk of cervical cancer, they also know that early screening uptake can detect an abnormal growth in the cervix but they lack the knowledge of what cervical cancer screening test is commonly called. This can be attributed to the low level of awareness of this disease among women of reproductive age in Nigeria. This result is in disparity with the study conducted among first year nursing students of KIU (2019)17 where all the respondents knew CCS and they all mentioned Pap smear as the screening test.

In this study, the respondents reported health workers and mass media to be their most sources of information. This is similar to Duru et al (2015)18 and llika (2016)19 where media and health workers were the most reported means of information.

Evidence have shown that, good attitude is needed for positive behavioral change as regards preventive practice of cervical cancer. The outcome of this study showed that, over half (52.0%) of the respondents had negative attitude towards cervical cancer prevention. Findings disagree with a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted by Mullatu et al, (2017)20 among Female students of Mizan Tepi university, it showed that, majority of the respondents 128(61.24%) had positive attitude towards screening while 81(38.76%) had negative attitude towards screening. The plausible reason to this could be due to unfiltered information from other sources of information aside health workers. This is evidenced in the result presented in table 4.3, where a significant part agreed that Human papilloma virus vaccine is meant for unhealthy individuals only. Result is also similar to Sajid et al., (2019)21, who found that, 87(51.4%) of the respondents said Cervical cancer screening is not important if there are no signs and symptoms.

The good knowledge exhibited by the respondents towards cervical cancer prevention did not translate to the level of practice. Findings revealed that, majority (77%) of the respondents had bad practices towards cervical cancer prevention. This is evidenced in the results presented where majority (74.5%) never undergo Human papillomavirus (HPV) test, (72.5%) never received Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine and (58.6) had never undergone cervical cancer screening, indicating a very low practice towards cervical cancer prevention amongst the respondents. This appears to be the case not only in this study, but also as an African problem, as several previous studies found a very low level of practice among respondents, even among those who are aware and knowledgeable about the importance of screening in the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer, as well as vaccination to prevent the manifestation of human papillomavirus on the surface of the cervix. This study corroborates with the one conducted by Nowomuhangi (2019)17 among first year nursing students in KIU who revealed that only 51% of the respondents had been screened for CC while only 39% had ever been vaccinated against HPV. Similarly, Oyekale et al (2021)22 found that, only (30%) of the respondents had ever undergone cervical cancer screening, another study conducted among female nurses working in healthcare facilities in Lagos state revealed that only 175 out of 232 respondents had been screened for cervical cancer.

CONCLUSION

The knowledge of reproductive age women towards CC prevention was above average while their attitudes towards cervical cancer prevention was low. The practice of CC prevention among reproductive age women was very poor requiring prompt and efficient interventions.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors listed in the articles have contributed significantly according to ICJME guidelines.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding received for the study.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval form for the study was submitted to the research ethnic committee of Adeleke University and letters of permission was retrieved and submitted to the registrars of the selected tertiary institutions. Only willing individuals were interviewed, written consent was obtained before interviewing respondents and they were treated with respect. Confidentiality of all information obtained in the course of this survey was assured and maintained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors will like to acknowledge all the respondents that took part in the study.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors declare that there is no competing interest.

References

- American society of clinical oncology. (2020). Cervical cancer Diagnosis and Stages. Knowledge Conquers Cancer.

- Saad A., Kabiru S., Suleiman H., Rukaiya A. (2013). Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening among Market Women in Zaria, Nigeria. Nigeria medical Journal vol.54. [CrossRef]

- Amine, C., Sanaa EL M., Nabil, I., Zakia, C., Jamal, B., Chakib, N., Amine EL H., Yahya C. and Noureddine, B. (2016). Evaluation of the Cost of Cervical Cancer at the National Institute of Oncology, Rabat. Pan African Medical Journal. Vol. 23. [CrossRef]

- Globocan. (2012). Cervical Cancer: Estimated Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

- World Health Organization. (2015). Cervical Cancer.

- Ajibola, I., Olowookere, S., Fagbemi, A. and Ogunlaja, O. (2016). Determinants of cervical cancer screening uptake among women in Ilorin, North Central Nigeria: a community-based study. Journal of cancer epidemiology. Vol. 2016, article ID 6469240, 8 pages. [CrossRef]

- Scott, A M., Venetia, Q., Johannes, B., Hester, M. and Johannes A. (2017). Disease Burden of Human Papillomavirus Infection in the Netherlands. The Gap between Females and Males is Diminishing. [CrossRef]

- Musa, J., Nankat, J., Achenbach, C., Shambe, H., Taiwo, O., Mandong, B., Daru, P., Murphy, R. and Sagay, S. (2016). Cervical cancer survival in a resource-limited setting-North Central Nigeria. Infect. Agents Canc., vol.11 (1) (2016), p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., and Tanya, S. (2014). A Study on Knowledge and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Women in Mangalore City. Ann Med Health Sci Res. [CrossRef]

- Jermal, A., Center, M., DeSantis C., and Ward EM. (2010). Global Patterns of Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 19(8):1893-907. [CrossRef]

- Saslow, D., Solomon, D. and Lawson, H. (2012) American cancer society, American society for colposcopy and cervical pathology, and American society for clinical pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 147–172. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2014). Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice.

- Okonufua, F. (2007). HPV Vaccine and Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Africa. AFR J Reprod Health.

- Adebayo M. and Oluwasomidoyin O. (2021). The Determinants of Knowledge of Cervical Cancer, Attitude towards Screening and Practice of Cervical Cancer Prevention amongst Antenatal Attendees in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. [CrossRef]

- Ekwonwa E., Olariike K., Abayomi O. and Ugushida O. (2020). Awareness, Knowledge and Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening among Women of Reproductive Age in Selected Wards in Ede South Local Government Area, Osun State. East African Scholars Journal of Medical Sciences.

- Ogbonna, F., and Med, A. (2017). Knowledge, Attitude, and Experience of Cervical Cancer and Screening among Sub-Saharan African Female Students in a UK University. National Library of Medicine 16(1): 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Nowomuhangi B. (2019). Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Cervical Cancer and Screening among First Year Female Nursing Students of Kampala international university.

- Duru, C., Oluoha, R., Uwakwe, K., Diwe, K.C., Merenu, I., Emerole, C., and Iwu, C. (2015). Pattern of Pap Smear Test Results among Nigerian Women Attending Clinics in a Teaching Hospital. Int.J. Curr. Microbial. App. Sci, 4(4),986-998.

- IIika, I., Gani O., and McFubara K. (2013). Cervical Cancer Screening among Female Undergraduates and Staff in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gnecology. [CrossRef]

- Mulatu, K., Ayalew, M., Melkam., and Mulugeta, T. (2017). Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Cervical Cancer Screening among Female Students of Mizan Tepi University, Ethiopia. Cancer Biol Ther Oncol.

- Sajid et al., (2019). Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards cervical cancer screening among female health care professionals.

- Rahmat, A., Abimbola, O., and Olaide E. (2021). Predictors of Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening among Nurses in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. Vol. 15. [CrossRef]

Figure 3.

Overall practice of cervical cancer prevention.

Table 3.

Attitude of Respondents on Cervical Cancer Prevention (N=396).

| s/n | Variables | SA | A | N | D | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human papilloma virus vaccine is meant for unhealthy individuals only | F | 74 | 78 | 51 | 95 | 98 |

| % | 18.7 | 19.7 | 12.9 | 24.0 | 24.7 | ||

| 2 | Cervical cancer screening is meant for only those who are sick | F | 43 | 51 | 33 | 101 | 168 |

| % | 10.9 | 12.9 | 8.3 | 25.5 | 42.4 | ||

| 3 | Having multiple sexual partners can increase the risk of cervical cancer | F | 155 | 155 | 59 | 21 | 6 |

| % | 39.1 | 39.1 | 14.9 | 5.3 | 1.5 | ||

| 4 | HPV is transmitted through sexual intercourse | F | 139 | 141 | 94 | 17 | 5 |

| % | 35.1 | 35.6 | 23.7 | 4.3 | 1.3 | ||

| 5 | HPV can increase the risk of cervical cancer | F | 140 | 114 | 73 | 57 | 12 |

| % | 35.4 | 28.8 | 18.4 | 14.4 | 3.0 | ||

| 6 | Early marriage onset is a risk to cervical cancer | F | 87 | 105 | 76 | 87 | 41 |

| % | 22.0 | 26.5 | 19.2 | 22.0 | 10.4 | ||

|

7 |

Cervical cancer is a major health problem for women |

F |

166 |

98 |

66 |

46 |

20 |

| % | 41.9 | 24.7 | 16.7 | 11.6 | 5.1 | ||

| 8 | Early diagnosis of premalignant lesions is good for treatment outcome | F | 183 | 126 | 63 | 24 | 0 |

| % | 46.2 | 31.8 | 15.9 | 6.1 | 0.0 | ||

| 9 | Cervical cancer is preventable | F | 188 | 117 | 62 | 8 | 21 |

| % | 47.5 | 29.5 | 15.7 | 2.0 | 5.3 | ||

| 10 | Cervical cancer is curable | F | 137 | 117 | 51 | 45 | 46 |

| % | 34.6 | 29.5 | 12.9 | 11.4 | 11.6 | ||

| 11 | Early screening can help detect the onset of premalignant lesions | F | 167 | 105 | 66 | 21 | 37 |

| % | 42.2 | 26.5 | 16.7 | 5.3 | 9.3 |

Table 4.

Association between Knowledge of Reproductive Age Women and Prevention of Cervical Cancer.

| Categories | Knowledge on Cervical Cancer prevention |

χ2 | p-value | Decision | ||

| Low | High | |||||

| Prevention of cervical cancer | Good | 153 | 152 | 2.537 | .121 | Not sig. |

| Poor | 37 | 54 | ||||

Table 5.

Association between Attitude of Reproductive Age Women and Prevention of Cervical Cancer.

| Categories | Attitude towards cervical cancer prevention | χ2 | p-value | Decision | ||

| Negative | Positive | |||||

| Prevention of cervical cancer | Good | 158 | 147 | .025 | .905 | Not sig. |

| Poor | 48 | 43 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated