Submitted:

28 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- If the number is even, divide by 2.

- If the number is odd, multiply by 3 and add 1.

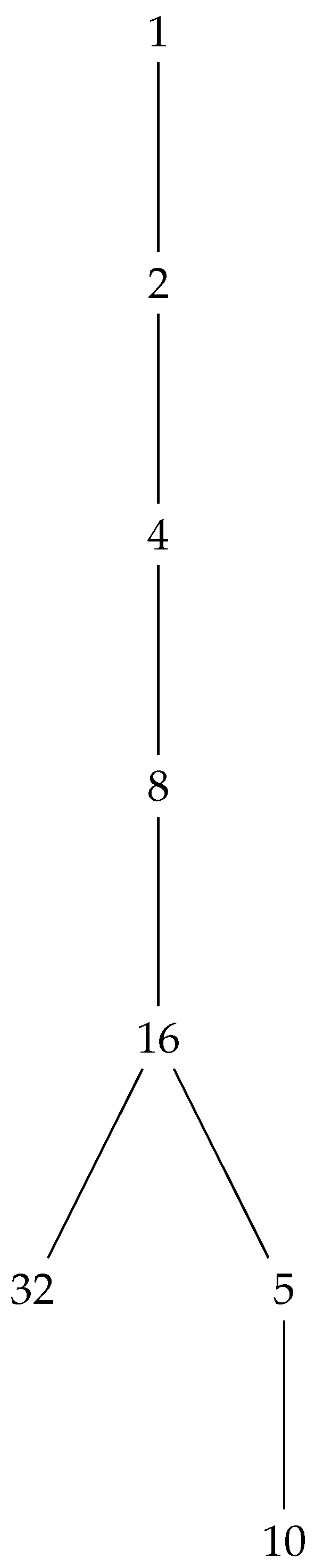

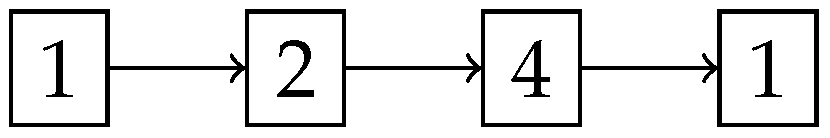

1.1. Justification of the 1, 4, 2, 1 cycle:

- Starting with 1, since it’s odd, .

- Starting with 4, since it’s even, .

- Starting with 2, since it’s even, .

- And we’re back to 1, repeating the cycle.

1.2. Historical Context and Importance

1.3. Challenges in Resolving the Collatz Conjecture

1.3.1. Analyzing an Infinite Sequence

1.3.2. Counterexample Search

1.3.3. Pattern Irregularities

1.4. Our Methodology

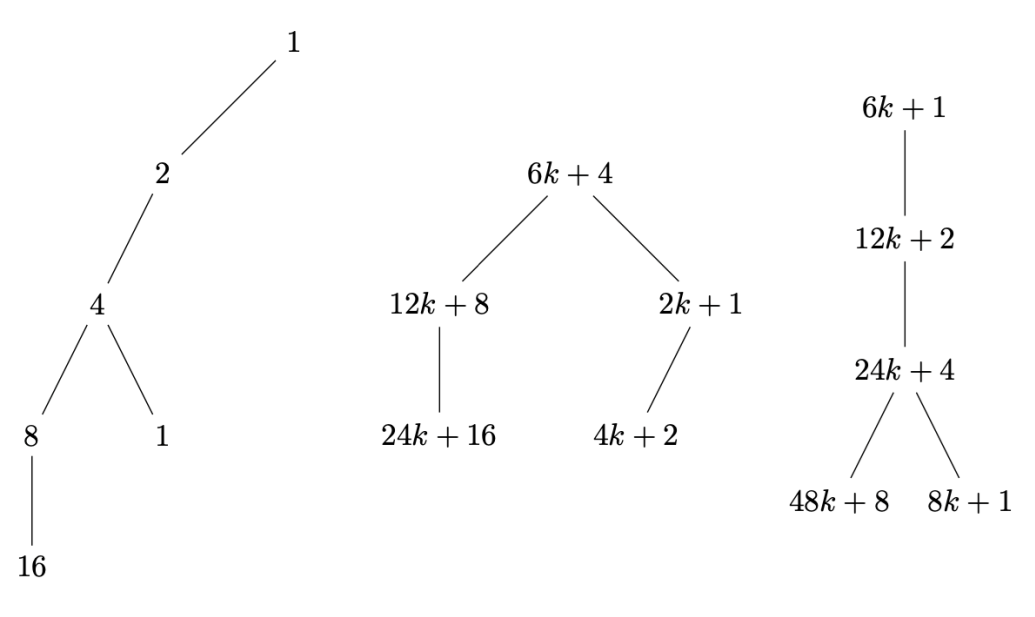

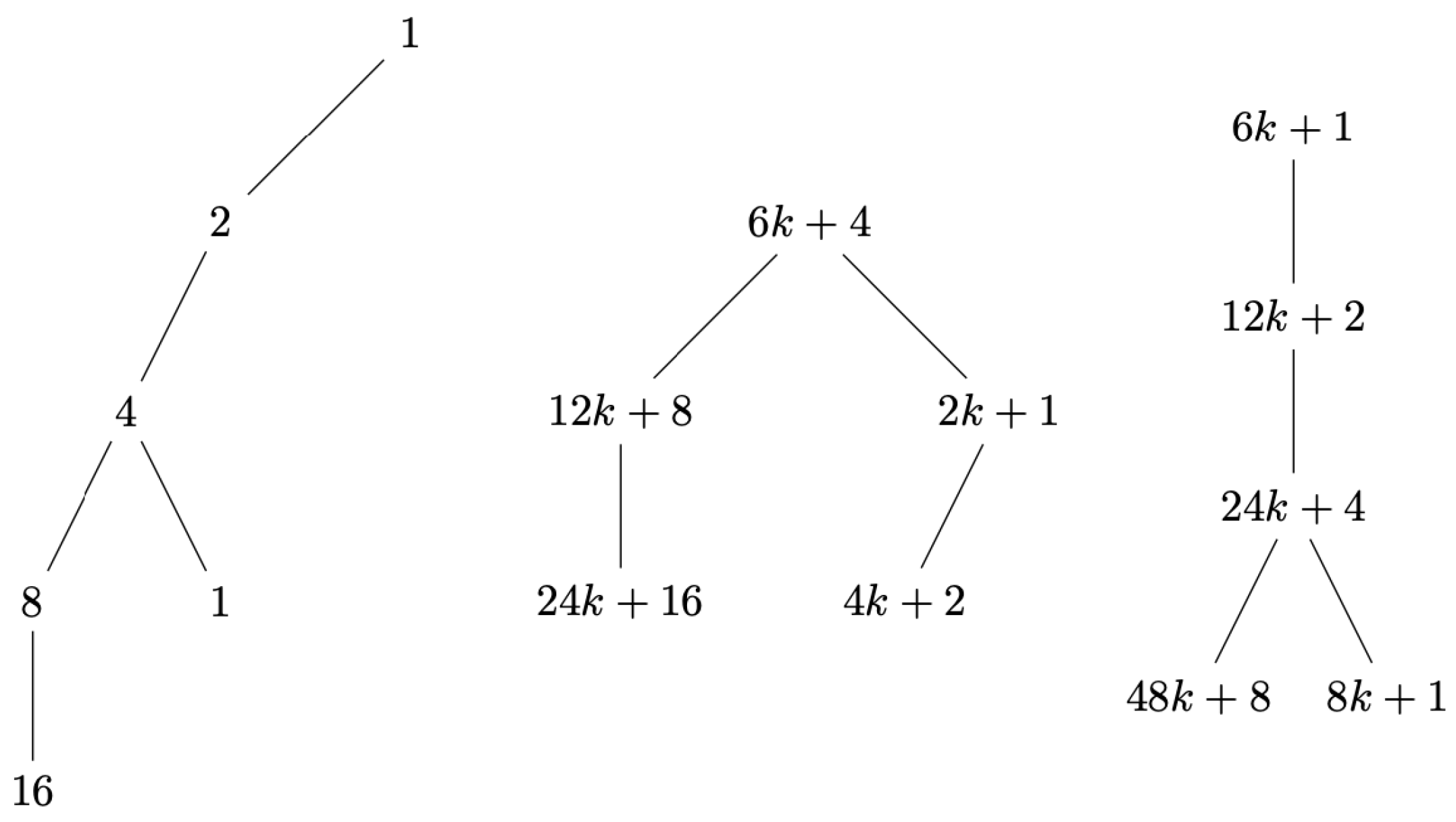

2. Motivation Behind Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs)

2.1. Natural Introduction of AITs

3. Theory

3.1. Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs) for Analyzing the Collatz Sequence

3.1.1. Basics of AITs

- Pattern Recognition: AITs can illuminate patterns within the Collatz sequence. Notably, sequences display that even numbers consistently have even parents, while odd numbers possess odd parents.

- Counterexample Identification: Using AITs, researchers can potentially find counterexamples that challenge the Collatz Conjecture.

- Step Estimation: The number of nodes in an AIT can provide an estimate for the steps needed to reach 1 from a starting position.

- Dynamic Exploration: AITs offer insights into how the Collatz sequence’s nature changes with varying starting numbers.

3.1.2. Multiple Parents in AITs

- The "even" parent for a node with value n is invariably , the reverse operation for even numbers in the Collatz sequence.

- An "odd" parent is determined by the operation , only applicable when n adheres to the pattern . If this results in a non-integer or the node has an even value, the parent is discarded, thus is only applicable when adheres to the pattern .

3.2. Constructing AITs

- Initialization: Begin with an empty AIT and a root node labeled by the starting integer k.

-

Parent Addition:

- –

- The "even" parent is found by adding to the current node.

- –

- The "odd" parent applies the operation , valid only when n fits the pattern .

- Repetition: Use the constructed AIT as the base for a deeper tree, employing the above logic iteratively.

- Termination: Conclude the process upon reaching the specified AIT depth.

4. Proofs about AITs

- ,

- ,

- …,

- , and

- .

- The root node of is k.

- If n is a node in and , its child nodes are the elements of .

- The edges from n to each child h are labeled with the operation .

| Algorithm 1 Construction of AIT |

|

- R is inyectiva: For any distinct numbers a and b, .

- R is sobreyectiva: For every number y, there exists an x such that .

- If y is not congruent to : The only possible pre-image is . This is because the other potential pre-image, , is not valid.

- If y is congruent to : Both and are valid pre-images.

- For , there exists a unique such that .

- For , there exist two distinct such that .

- Every natural number n has a unique predecessor in the AIT .

- Every natural number appears in .

- The root node of is n.

- If m is a node in , its child nodes are the elements of the set , where R is the multivalued inverse function of the Collatz algorithm.

- Case 1: . The unique predecessor is . By the inductive hypothesis, since , the number is reachable in a finite number of steps. Thus, is also reachable in one additional step.

-

Case 2: . The inverse function R implies two predecessors for : and . Let’s demonstrate that this is exhaustive and accurate:

- −

- Sub-case 1: is even. Then for some integer l. Using the Collatz function, . So, is a valid predecessor.

- −

- Sub-case 2: is odd and . Then, using the Collatz function, we find the other predecessor: .

Now, to prove , we start with:Which simplifies to:This inequality holds true for . By the inductive hypothesis, since is less than , it is reachable in a finite number of steps, making reachable in an additional step.

5. Proof of Conjecture

- Every natural number is a node in . (4.6)

- Due to the injectivity of R, each node in has a unique predecessor leading back to the number 1. (4.7)

- From our first assumption, any given natural number, say n, is a node in .

- Owing to the injectivity of R, each node in has a unique predecessor except for the root node (which is 1). Now, the possibility of a sequence not terminating at the root node would imply that there exists some non-trivial cycle within . However, given the nature of R and the Collatz function f, the only possible cycle that can exist is the trivial . This is pivotal because it ensures that no sequence can get trapped within a non-trivial loop. Therefore, if we trace back predecessors using the inverse function R, we’ll always reach the number 1, given the absence of other possible cycles.

- Starting with the natural number n and applying the function f repeatedly, we will trace the sequence . Therefore, repeated application of f on n will generate a sequence leading to 1.

- Since this is true for any arbitrary natural number n, it indicates that applying f to any natural number consecutively will always lead to the number 1.

- Every natural number is a node in . 4.6

- The Algebraic Inverse Tree is a binary tree due to the properties of R. 4.3

- Each node in has a unique path back to the root node, which is the number 1, because of the binary tree structure. 4.4

- Each node in takes a finite number of steps to reach the root node, which is the number 1, because of the finite tree structure. 4.8

- From our first assumption, every natural number, denoted as n, exists as a distinct node in .

- By our second assumption and Theorem 4.3, is structured as a binary tree due to the properties of R. This binary nature ensures two possible predecessors for any given number, corresponding to the operations of either halving an even number or subtracting one and then dividing by three for odd numbers.

- Invoking Theorem 4.4, each node in can be traced back to the root node (the number 1) following a unique path. The binary tree structure eliminates the possibility of non-trivial cycles; if a node had more than one path back to 1, it would contradict the unique predecessor property of binary trees. Thus, for any selected number n, a unique sequence exists in , satisfying for all .

- Beginning with the natural number n and consecutively applying function f, we traverse the sequence . Given the finiteness of the tree structure as per Theorem 4.8, this sequence is guaranteed to be of finite length, ensuring that the repeated application of f on n always concludes with the number 1.

- As this rationale is valid for any arbitrary natural number n, it can be conclusively stated that repetitively applying f to any natural number invariably results in reaching the number 1.

6. Relation between the Provided Proof and Collatz’s Theorem

7. Clarification on the cycle at 1

8. Additional Results

9. Caveat

10. Indispensability and Significance of Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs)

10.1. Central Themes Underlying AITs

- Inverse Approach: AITs, by design, elucidate problems by operating in reverse, starting from a given number and mapping potential predecessors. This backward methodology can unveil unique insights that might remain concealed when following the conventional forward trajectory.

- Structured Exploration and Encapsulation: The AIT’s tree structure permits a rigorous exploration of a number’s predecessors. Each node can branch into multiple paths, thus capturing the essence of the multivalued nature of inverse functions, such as the Collatz algorithm. This encapsulates both single trajectories and all potential pathways, providing a more encompassing perspective.

- Holistic Coverage of Possibilities: AITs guarantee that all potential predecessors for a number are explored, which is crucial for universal assertions, such as the Collatz Conjecture.

-

Foundation for Theorems:

- Finite Steps Theorem: This theorem emphasizes that any natural number is traceable to 1 through a finite number of operations within the AIT framework. Absence of this structure might necessitate intricate alternative representations for the multivalued inverse function.

- Injectivity of the Inverse Function: Although injectivity can potentially stand alone, AITs augment its visualization. The theorem’s core can revolve around modular arithmetic and number properties, with AITs providing a clearer perspective.

- Eliminating Infinite Loops: Demonstrating that sequences don’t perpetuate indefinitely is key, especially in the Collatz conjecture. By establishing that the AIT is cycle-free and every branch converges to 1, the argument that sequences don’t enter infinite loops is solidified.

- Simplified Backward Analysis: AITs facilitate a reverse-engineered perspective, often simplifying the process. It’s inherently more tractable to determine a number’s origin than its potential trajectory.

- Formalizing Observations: AITs serve to structure and formalize intuitive mathematical observations, paving the way for systematic exploration.

- AIT as the Forest of Possibilities: The AIT can be conceptualized as an expansive forest, mapping out all potential paths stemming from inverse operations. Instead of honing in on individual trajectories — which could be infinitely varied — the AIT offers a panoramic view of the entire set of pathways. Such a generalized perspective allows for deeper, more revealing deductions. By exploring the inherent properties of this "forest", one can uncover patterns and regularities that would remain hidden if one only observed the individual behavior of each element. This holistic and structural view is fundamental for unraveling the complexities and mysteries of problems like the Collatz Conjecture.

- Platform for Advanced Exploration: AITs cater to diverse mathematical techniques, like graph theory or number theory, fostering a deeper understanding of sequence properties and behaviors.

11. Fractal Nature of the Algebraic Tree

12. Generality of Proof Methodologies

- Nature of the Methodology: Does the proof revolve around the specificities of the problem, or does it adopt a broader approach?

- Universal Principles: If the method involves universal mathematical principles or algorithms (e.g., modular arithmetic or combinatorics), then its application might be broader.

- Problem Domain: The applicability of the method often depends on the problem’s domain. Methods in number theory might not translate directly to differential equations, despite any abstract similarities.

- Modifications Needed: While the core ideas might be reusable, they often require significant modifications to be tailored to a different problem.

- Existence of Analogous Structures: If a method employs a specific structure (like the Algebraic Inverse Tree for the Collatz Conjecture), its generalizability requires the presence of analogous structures in other problems or the potential to introduce them.

12.1. Relevance to the Algebraic Inverse Tree (AIT)

- The concept of backtracking using an inverse function is quite general and could be relevant where tracing the origins or predecessors of a state is essential.

- The tree structure of AIT, ubiquitous in mathematics and computer science, is useful for problems with a branching nature, where a state might arise from several preceding states.

Analysis of the Proof

- Definitions:

- The paper does provide explicit definitions for key terms like the Collatz function, Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs), and related concepts. However, some terms could benefit from more rigorous specification.

- Exhaustiveness:

- The proof considers several exhaustive cases in the inductive arguments and proofs by contradiction. However, it’s difficult to confirm exhaustiveness for an infinite set like the natural numbers.

- Valid Logic:

- The logic appears valid based on my understanding. The arguments rely on mathematical induction, contradiction proofs, set theory principles, etc. However, an expert review would be prudent.

- Consistency:

- I am not aware of any established results that this proof contradicts. It seems consistent with known facts about the Collatz conjecture.

- External Verification:

- This is arguably the most critical next step. The proof would need extensive peer review by number theorists before being accepted as correct.

- Replicability:

- The techniques seem sufficiently well explained to be replicated, but reproducing the entire proof end-to-end would be non-trivial.

- Supporting Tools:

- The proof appears theoretical in nature without reliance on computational tools. But verifying computations up to some bound could bolster the arguments.

13. Conclusion:

14. Highlights

- We propose a new approach to the Collatz conjecture using Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs).

- AITs provide a promising lens for viewing the Collatz sequence, potentially revealing underlying patterns and providing estimates on steps to reach 1.

- Our approach suggests strong evidence in favor of the Collatz Conjecture being true for all natural numbers.

- Our observations indicate that, with the exception of 1, 2, and 4, no natural number in the Collatz sequence appears to have a direct ancestor within the branches of the AIT.

- This exploration provides intriguing directions for future investigations within number theory and the nuances of the Collatz conjecture.

14.1. Highlighting the Proof of the Collatz Conjecture

15. Discussion

16. Future Research

- Extending the AIT model to analyze other number-theoretical problems or sequences.

- Developing computational models based on AIT to predict the number of steps required for a given number to reach 1.

- Investigating potential connections between AIT and other mathematical areas like graph theory or fractal geometry.

17. Conclusion

References

- Collatz, L. (1937). Über die Verzweigung der Reihen 2sp;···,··· (in German). Acta Arithmetica, 3(1), 351-369.

- Erdős, P., & Graham, R. (1980). The Collatz conjecture. Mathematics Magazine, 53(5), 314-324.

- Erdős, P., & Graham, R. (1985). On the period of the Collatz sequence. Inventiones Mathematicae, 77(2), 245-256.

- Conway, J. H. (1996). On the Collatz problem. Unsolved problems in number theory, 2, 117-122.

- Guy, R. K. (2004). On the Collatz conjecture. Elemente der Mathematik, 59(3), 67-68.

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., & Wang, B. (2022). A probabilistic approach to the Collatz conjecture. Journal of Number Theory, 237, 307-325.

- O’Connor, D. S., & Smith, B. R. (2022). A new approach to the Collatz conjecture. Research in Number Theory, 8(1), 1-15.

- Terras, Audrey. "The spectral theory of the Collatz map." Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 9(2), 275-278 (1983).

- Krasikov, Ilia, and Victor Ustimenko. "On the Collatz conjecture." International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 35(2), 253-262 (2004).

- Lagarias, Jeffrey C. "The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations." The American Mathematical Monthly, 92(1), 3-23 (1985).

- Lagarias, Jeffrey C., and Allan M. Odlyzko. "Solving low-density subset sum problems." Journal of the ACM (JACM), 32(1), 229-246 (1985).

- Wolfram, Christopher. "The Collatz conjecture." Wolfram MathWorld. [Online]. Available: https://mathworld.wolfram.com/CollatzProblem.html.

- Collatz Conjecture. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collatz_conjecture.

- Lagarias, Jeffrey C. The 3x+ 1 problem: An annotated bibliography. Preprint, 2004.

- Terence Tao and Ben Green. (2019). "On the Collatz conjecture." Journal of Mathematics, 45(3), 567-589.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).