Introduction

The link between food and quality has been tested in numerous studies, but this consideration is at its peak in post-pandemic conditions. In recent years, given ever specific demand for healthy food consumption, people buy more and more balanced and nutritious food to satisfy their health well-being (Tarabella, Apicella, Tessitore, & Romano, 2021; Anastasiou, Miller, & Dickinson, 2019; Cecchini & Warin, 2016). Since healthy and eco-friendly food consumption positively impacts health, higher authorities regarding the health sector distinguish quality aspects. Due to the recent pandemic situation, eco-friendliness is mainly associated with eatable products. This trend shifting is becoming a lifestyle in numerous countries and has a check on quality standards for eatable products (Yang, 2020; Majid, Hanan, & Hassan, 2020).

Customers now require wholesome food that meets their expectations and beneficial aspects of a meal. As an aspect of healthy good quality food, seafood is recommended by World Health Organization (2017) because two meals consumption of seafood per week positively influences consumer health (Allegro, et al., 2021). Moreover, with a growing trend in world population, technological advancement, and taste preferences, the importance of the food industry in contemporary society is proliferating. The dependability on consumer culture, intensive production of eatable products and massive exploitation of natural resources are becoming the reason behind environmental problems resulting in adverse effects on human health (Belyaeva, Rudawska, & Lopatkova, 2020; Topleva & Prokopov, 2020). Due to these aspects, marketing is playing a vital role in the food sector among various factors that influence food habits (Tarabella, Apicella, Tessitore, & Romano, 2021; Nielsen, 2018).

Hence, recent studies have considered various aspects of marketing to tackle behavioral characteristics of an individual by considering the green marketing mix as ‘knowledge of environment-friendly things’ (Tariq, Badir, & Chonglerttham, 2019). It has occupied the mind and imagination from the late twentieth century. Furthermore, Guerrilla, Covert, and Overt are also essential factors as antecedents of building positive behavior. Guerilla Marketing is defined as an umbrella term for unconventional advertisement campaigns that aim to draw the attention of a large number of recipients to the advertising message at comparatively little cost by evoking surprise and diffusion effects (Sinha & Student, 2019).

Similarly, covert marketing is the foundation of freedom of choice, consciousness and modification. It helps the marketers to promote their products in movies to have some positive outcomes regrading consumer perception building (Sabir, et al., 2014; Kiran, Majumdar, & Kishore, 2012). The marketers have identified various positive outcomes, but intention building was found on the peak (Skiba, Petty, & Carlson, 2019). One of the key features of covert marketing is that it is used to understand and capture the weakest level of the customer, and implement it to connect with them (Kaikati, J., & Kaikati, 2008). Likewise, it is the method that has no purpose of maximizing the sale but gave a substitute to guarantee the positive attitude of the customers toward brand and advertisement (Taylor, 2003).

Thus, marketing mix and its implication in green marketing are considered as a crucial topic in the research by various recent studies (Joshi & Patel, 2020; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020; Nur, Akmaliah, Chairul, & Safira, 2021; Hayat, Nadeem, & Jan, 2019). However, there is a paucity concerning research in the current field regarding an integrated model for marketing mix, attitude, brand evangelism, intentional, and buying behavior (Piroth, Ritter, & Rueger-Muck, 2020; Karunarathna, Bandara, Silva, & De Mel, 2020; Zaky & Purnami, 2020). This behavior building is a broader concept that needs to be studied comprehensively in various contexts and settings (Migliore, Thrassou, Crescimanno, Schifani, & Galati, 2020; Zheng, Siddik, Masukujjaman, Alam, & Akter, 2021). A paucity of empirically tested evidence was also discovered regarding the use of covert and guerrilla marketing in the food industry of developing countries (Serazio, 2021; Evans & Wojdynski, 2020). These concepts could be used as intention builders for green marketing due to the current pandemic situation of COVID-19 over the globe.

Based on these arguments, the present study proposes a model to fill a literature gap regarding the integration of marketing mix and new marketing concepts like Covert, Overt and Guerrilla Marketing in the food industry (Zhang, 2020; Wojdynski & Evans, 2020; Rosenbaum, Ramirez, & Kim, 2021). Moreover, Vila-Lopez and Küster-Boluda (2020) elaborated a gap for empirical studies regarding the consideration of environmental factors on behavior building after reviewing 1,170 research studies based on a qualitative survey in food packaging. Recent literature on green marketing and buying behavior in pandemic conditions has also directed the researchers to consider environmental factors such as ecological knowledge on behavioral building (Sun, Su, Guo, & Tian, 2021; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020; Karunarathna, Bandara, Silva, & De Mel, 2020). The present study also contributes by incorporating environmental aspects in the proposed model in which these aspects have considerable importance. Lastly, the study would use online and offline data collection methods recommended in the existing literature (Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020). Despite COID-19 pandemic conditions, brands are trying hard to use green marketing practices to attain and sustain their customers through various marketing tactics in which covert and guerrilla advertising indirectly captures customer's attention. The present study would provide empirical justification of the importance of different marketing tactics in the behavior building of target customers of the Food industry of Pakistan. The study would be beneficial not only for marketing agencies but also for the brands to deal with customer’s mindset regarding their products and marketing activities used by brands.

Literature Review

Marketing Mix Product and Price

Even though the concept of green marketing has been discussed in earlier literature, it became an underpinning topic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Research seminar on "Ecological Marketing" by American Marketing Association in 1975 produced a book on green marketing entitled “Ecological Marketing” (Rudi, 2009). A process of producing and promoting environment-friendly products or services is considered under the umbrella of green marketing. Due to environmental considerations and global warming consequences, companies should use these green marketing tactics to produce and deliver environment-friendly products (Sembiring, 2021). Literature also discusses this as a concept, which includes numerous activities related to development to stimulate and sustain eco-friendly customer's attitude and behavior (Joshi & Patel, 2020; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020; Nur, Akmaliah, Chairul, & Safira, 2021; Zheng, Siddik, Masukujjaman, Alam, & Akter, 2021). Literature evident nemorous aspects of marketing mix i.e. 7 P’s and 4 P’s as the key elemnts for marketing mix startregies.

Green Product Features

Now talking about marketing mix dimesnsions i.e. product and proice, firstly in green or eco-friendly marketing mix product plays a central role; however, it should keep in mind that green product is not just limited to its core objective, but it also involves various elements linked with the product, such as materials, production process and others (Cullington & Zeng, 2011). Literature also suggests that green products are not harmful to humans and the environment in all aspects but mainly in their production, usage, and disposal of these products (Junaedi, 2015). Literature also indicates that green products are produced using environment-friendly measures, especially non-toxic licensed ingredients, and those that directly affect humans like eatable or cosmetic products (Kumar & Ghodeswar, 2015). These products should consider the environmental aspects in their life cycle to minimize the negative influence on their surroundings. These efforts to mitigate adverse effects encourage all participants to play a crucial role in technology development toward building environment-friendly green products.

Green Price

The pricing component is the most critical factor of green marketing integration. Research regarding marketing mix states that price is the cost or economic factor associated with any product/service, which is also considered a vital element of the marketing mix. A number of individuals intend to buy any product just because they are well prepared to pay a premium price if that product meets their expected value in their mindset (Sembiring, 2021). The green price refers to a specific price by the company relating to a specific product that assures environmental considerations and regulations (Hashem & Al-Rifai, 2011). Green products often seem to have a higher price than other traditional products in the same category because most of these products contain high initial or primary costs, but eventually, they provide better output in the long run. Researchers also enlighten the issue that the price component of any green product must be reasonable, inspiring the customers to prefer these products to other conventional products, especially dealing with the customer line of developing economies (Yazdanifard & Mercy, 2011). Summing up all these aspects, it was recommended in earlier studies that green products should have a balanced pricing consideration for their functionality and value provision, mostly dealing in eatable products (Saremi, Nezhad, & Tavakoli, 2014).

Covert, Overt and Guerrilla Marketing

Covert Advertising can be explained with the example from a group of friends who meet on a summer vacation weekend and go outside for cooking and pleasing themselves. One of the friends repeatedly promotes a sausage by saying this is his favorite. That friend was actually associated with the company but hid his connection to promote that sausage. Many people use that sausage just because of the recommendation of their groupmate. These people, and those who heard their friend’s sausage references, were influenced due to covert marketing tactics (Boyer, Boyer, & Brent Baker, 2015).

Table 1 summarizes the type of marketing and its message conveying to the target audience through these two techniques (Boyer, Boyer, & Brent Baker, 2015).

In typology, the element specified as the real source is the message owner and the company that initiates the communication process. The real source can explain or disclose its true identity to the recipient in the message transmission process, or it is possible to hide it (Lu, Chen, & Wang, 2020; Skiba, Petty, & Carlson, 2019). The prepared message can also be transmitted explicitly or implicitly to the recipient. Each cell was named as traditional techniques, indirect techniques, masked techniques and fox techniques depending on the level of cover.

Covert advertising is a product or brand embedded in entertainment and media. In other words, branding of various products by placing them within films or television programs where the audience may not realize is another form of advertising. Similarly, literature also believes that advertisers use various techniques in order to conceal such intentions smartly (Lu, Chen, & Wang, 2020). Advertisers use covert communication as an effective way to persuade the audience to buy their products. According to Aka et al. (2015), advertising affects the behavioral pattern of consumers and ensures the patronage of the advertised brand. It makes use of messages channeled through the right medium, that is, the medium mostly used by potential customers (Newspapers, TV, Radio and Billboard). So, advertising works with the right message channeled through the right media to the right audience.

Guerrilla Marketing

Business entities use another emerging strategy called guerrilla marketing to meet their value preposition and deliverability to customers. There are numerous definitions of this concept; initially, guerrilla marketing was defined as the set of marketing tactics that can be planned and implemented to a specific audience at low cost to have a marketing edge over the other competitors (Fong & Yazdanifard, 2014; Caldwell, Osborne, Mewburn, & Crowther, 2015). Some other recent literature also defines it as the advertising strategy which is designed to promote business and its products/services through unconventional tactics in a low budget which has a long-lasting impact on customer's mindset in building positive and strong perception for a brand (Vasileva & Angelina, 2017; Dinh & Mai, 2015).

As compared to other marketing tactics, guerrilla marketing has some advantages and disadvantages. Talking about its benefits, it is cheap, has a long-lasting impact on customer minds, is highly reliable, has a high level of efficacy. So, the delivered message can cover the mass audience effectively and rapidly through attractive tactics and fun, and most importantly, it multiplies the company's profit by giving them a competitive edge (Gökerik, Gürbüz, Erkan, Mogaji, & Sap, 2018). Now talking about its disadvantages, it has a level of ignorance risk, and secondly, due to its rapid reach, the uncertain negativity can also be spread rapidly through negative experiences or statements.

Literature also shows that guerrilla marketing focuses on human behavior and psychological aspects, unlike conventional marketing strategies, which provide a platform to invest your time, gain knowledge, and build perception for buying efforts. It is also described that this technique has over 200 sub tactics that a business can choose parallel to their product and target customers. In marketing terminologies, this mainly focused on "You" rather than "Me" for building a long-lasting loyalty bond with customers (Caldwell, Osborne, Mewburn, & Crowther, 2015; Vasileva & Angelina, 2017; Gkarane, Efstratios-Marinos, Vassiliadis, & Vassiliadis, 2019). Guerrilla marketing is also a key tactic to enhance the company's brand image in generation Y consumers (Gökerik, Gürbüz, Erkan, Mogaji, & Sap, 2018; Serazio, 2021). So, a positive image of a company can be built symbolically and experientially with the help of guerrilla marketing (Soomro, Baeshen, Alfarshouty, Kaimkhani, & Bhutto, 2021). Summing up the literature, past findings concluded that guerrilla marketing is the most considerable communication and promotional tool while having limited marketing costs, which has a long-lasting impact on customer's mindset.

Intention and Behavior

Green Purchase Intention

According to Grewal, Monroe and Krishnan (1998, p.52), purchase intention can be defined as “a probability that lies in the hands of the customers who intend to purchase a particular product”. Consumers’ choice to buy a product (purchasing intention) depends largely upon the value of the product and opinions that other consumers have been sharing on various platforms. In other words, it is the possibility of buying a specific product or service in the near or far future. This intentional component is also considered as the most encouraging factor for an individual to execute its actual purchase or not (Arslan & Zaman, 2014; Kotler, Philip & Keller, 2012).

The study also segregates the intentional concept as initially a state when a desire to own a thing is raised, next phase is about buying interest whereas an individual is affected through various product-related aspects, i.e., brand name, quality, and the price comparison with other brands in the same product category (Durianto, 2013). The business has to keep an eye on this intention, which can be executed through various marketing tactics. Viral marketing is also a key concept from these tactics created by the organization and word of mouth generated by the consumers leads to impulsive progressing and approval by users who find the brand having the value to be considered (Hoy & Milne, 2010).

Empirical findings further reveal that attitude toward the sustainable brand and environment consciousness is the highest driving factor that raises purchase intention for buying green products, whereas risk perception plays a significant negative role in this relationship (Mataracı & Kurtuluş, 2020; Rausch & Kopplin, 2021). Another study (Tseng & Chang, 2015) also targeted exploring the antecedents and consequences for intention to buy organic products. The results disclosed that in a high level of conscious behavior, the utilitarian and hedonic values of an individual have the most substantial impact on intention building. The researchers also concluded that brands could educate customers through various marketing tools, providing a fruitful result in intention building. Similar to these findings, the literature also direct marketers that they need to understand how they can raise the level of green conscience. Furthermore, they also revealed that green conscience and consumer altruism are the important factors for increasing buying intention and building customer loyalty (Panda, et al., 2020).

Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior

Ecological conscious consumer behavior (ECCB) refers to the conceptualization of individual’s orientation toward presentation and concern to the environment (Zhao, Gao, Wu, Wang, & Zhu, 2014). Being concerned for the environment is a favorable factor in behavior building; however, conscience toward green products and commitment toward the environment are critical factors in building ECCB (Prakash & Pathak, 2017). Aligned with these findings, recent researchers found that customers intend to switch to green ecological products and brands from non-green products due to climate and pandemic situations over the globe (Sajjad, Asmi, Chu, & Anwar, 2020). The researchers reviewed various factors that influence consumer ecological conscious behavior in recent decades, especially in the food industry. After extracting multiple factors from exiting studies, a recent study in the Asian context shows that health-conscious consumers regarding the food industry have more ecological behavior. This attitudinal shift is due to various health issues, especially during the pandemic situation facing the globe (Rana & Paul, 2017). The consumers who are characterized to any specific market segment consider environmental consideration while buying and consuming. This segment mostly believes in personal self-improvement and takes initiatives regarding adopting the ecological lifestyle, i.e., introducing others regarding the protection of the environment, consciousness for the environment, voluntary role in various events. Most considerably, their selection criteria are based on environmental factors (Paul & Rana, 2012).

Researchers also explore the antecedents and consequences for building conscious ecological behavior by disclosing that consumer ecological behavior is mainly affected through subjective norms and attitudinal factors. These factors play a vital role in building ecological behaviors (Tseng & Chang, 2015). Likewise, research also determines that various socioeconomic levels are essential in deciding ecological behavior among customers of developed economies (Mataracı & Kurtuluş, 2020). Studies regarding sustainable behavior among youngers also show that individuals of developing countries for this age group are more concerned than various American and Russian countries (Kumar, Prakash, & Kumar, 2021).

Environmental Knowledge

The concept of environmental knowledge is defined as the individual's knowledge and awareness of the concepts, facts, and issues regarding environment protection and ecosystems (Vicente-Molina, Fernández-Sáinz, & Izagirre-Olaizola, 2013; Goh & Balaji, 2016). In simple words, this concept encompasses whatever an individual knows about the environment, its relationship and influences, capability to understand environmental issues and their response and act for its sustainability (Jaiswal & Kant, 2018). Existing literature related to pro-environmental factors explores that ecological knowledge is formed by attitudes that reflect their buying behavior. Nevertheless, the findings also demonstrate that environmental knowledge is an important factor in building attitude toward brand, intention and green behavior (Kumar, Manrai, & Manrai, 2017; Jaiswal & Kant, 2018). It is also directed that both practitioners and researchers should consider it seriously in the future (Vicente-Molina, Fernández-Sáinz, & Izagirre-Olaizola, 2013).

Even though the concept of environmental knowledge seems like an essential factor to attain one’s attention toward pro-environmental ecological behavior building, it is also proven that knowledge about the environment is also helpful for the business world, so they can efficiently deliver their information about green marketing to the targeted audience (Mahmoud, Ibrahim, Ali, & Bleady, 2017). Some inconsistent findings also exist in the literature, like a study by Kumar et al. (2017) found that environmental knowledge is a positive and significant factor for building pro-environmental attitude, but discovered a weak and insignificant relationship with purchase intention in the context of Indian culture. Earlier research also uncovers the inverse findings by providing empirical results that environmental knowledge is a significant positive factor for green product buying intention building but insignificant for attitude (Vazifehdoust, Taleghani, Esmaeilpour, & Nazari, 2013; Aman, Harun, & Hussein, 2012).

Brand Evangelism

In a highly competitive market, the evangelist concept is an emerging trend for practitioners and researchers. Simply evangelism promotes anything by persuading others, and brand evangelism is also parallel to this concept; it talks about persuading others, which influences their buying intention (Hsu, 2019; Harrigan, Roy, & Chen, 2020). This concept of brand evangelism is considered as customer's supportive behavior and positive or negative saying about the brand, which can change purchase decisions. Literature also supports that brand customers could be evangelists for a brand, but key evangelists are the salespersons because they are working on the real ground to spread positive about the brand, and sells products or services (Mehran, Kashmiri, & Pasha, 2020).

The brands are now considering an evangelical marketing frame to market their products and services. Recently, a study (Sanjari Nader, Yarahmadi, & Balouchi, 2020) interrogates the role of brand evangelism variables in building customer-brand relationships. Findings show that customer-brand relationships in various brand communities are significantly and positively correlated with brand evangelism. In marketing, brand evangelism is also replacing word-of-mouth marketing due to more reliance on making a non-customer individual a loyal customer of the brand (Riorini & Widayati, 2016). Brand evangelism with co-creation and brand engagement was also a vital driver of positive brand evangelism (Harrigan, Roy, & Chen, 2020).

Habitat Attitude

Some studies also seemed that attitude is essential in building customer loyalty and purchasing intention (Rabbanee, Afroz, & Naser, 2020). This habitat attitude is also related to the environment, which discloses the attitude toward environmental factors. The literature discusses well about attitudes of customers, especially for cognitive characteristics and association with pro-environmentalism, empirical findings discussed that attitude is the significant factor for intention building, especially regarding green products. It also seems that attitude is the subjective factor built through cognitive value propositions (Wang, Wong, & Alagas, 2020).

Numerous authors also support the relationship between attitudinal factors and intention building, like a study by Huang et al. (2014) revealed that attitude is a considered factor for purchase intention toward green products (Huang, Yang, & Wang, 2014). Furthermore, another study also seconds these findings by indicating that attitude toward green environmental friendliness plays a vital role in intention and behavior building (Chekima, Wafa, Igau, Chekima, & Sondoh Jr, 2016). In the same vein, the attitude concept in the context of green products is the most significant factor that positively influences purchase intention and purchasing behavior (Amoako, Dzogbenuku, & Abubakari, 2020; Fauzan & Azhar, 2019).

Hypotheses Development

Marketing Mix and Purchase Intention

Recently multi case-study-based research regarding retailers empirically found that digital and conventional marketing tactics will eventually positively influence marketing mix consequences— mainly product and price. Firstly, these tactics are grouped into product categories, and then this categorization associates the product with price factor, which lastly builds intentional factors (Gustavo Jr, et al., 2021). Research investigating consumer perception toward green products in building buying behavior suggests a significant relationship between these factors under the hood of signal theory and psychological ownership theory. These findings also direct the practitioners to consider green product factors in their marketing tactics (Kartawinata, Maharani, Pradana, & Amani, 2020; Chang, Chen, Yeh, & Li, 2021).

Evidence was founded in Indonesian culture regarding influence of social media on green products purchase intention. This shows that potential consumers tend to seek information about their expectations and prioritize the green product over other products in the same category (Mahmoud, 2018; Dewi, Avicenna, & Meideline, 2020). Product and price are the key components of the marketing mix, which play a crucial role in building one’s intention toward buying. Product and price are the main determinants for positively affecting an individual’s intention, especially in the food and beverages industry (Sembiring, 2021). These findings also direct practitioners that product and price are the most necessary elements of the marketing mix to increase the sales intention of the target audience.

Environment-friendly or green products include numerous aspects regarding environment friendliness, including its production, packaging, usage, and disposal. These products are primarily defined as a product/service offered by the company with some key environmental advantages that attract the consumers to buy compared to other conventional products in the same product category. Having a tag of environment-friendly for a product can positively affect the intentional factor of an individual (Mahmoud, Ibrahim, Ali, & Bleady, 2017; Shrestha, 2016). Similar to product, the pricing factor is also considered important for building the intention of an individual.

Green pricing is the economic or cost factor that any customer must bear for consuming any ecological product. The positive and ecological value deliverability can change once perception to buy the green product even at a high price compared to other available non-green products in the same product category (Gaidhani, Arora, & Sharma, 2019; Liana & Oktafani, 2020). Most of the time, the green eco-friendly products seem to have a high price due to increased production costs. While those customers who are concerned and proactive for environment sustainability can understand the price offered by the firm, and they still have a positive intention to buy these products rather than selection other conventional non-green products.

Customers do this their role in supporting the sustainability of the environment (Mahmoud, Ibrahim, Ali, & Bleady, 2017; Mahmoud, 2018). Another study in the context of green organic agricultural products revealed that these two components of the marketing mix are important in building ecological intention and behavior in customers, moreover also founded that customers are willing to pay more than a conventional product to buy a green environment-friendly product (Melović, Cirović, Backovic-Vulić, Dudić, & Gubiniova, 2020). This shows the shift of customer minds toward green products, considering the environment while building intentions.

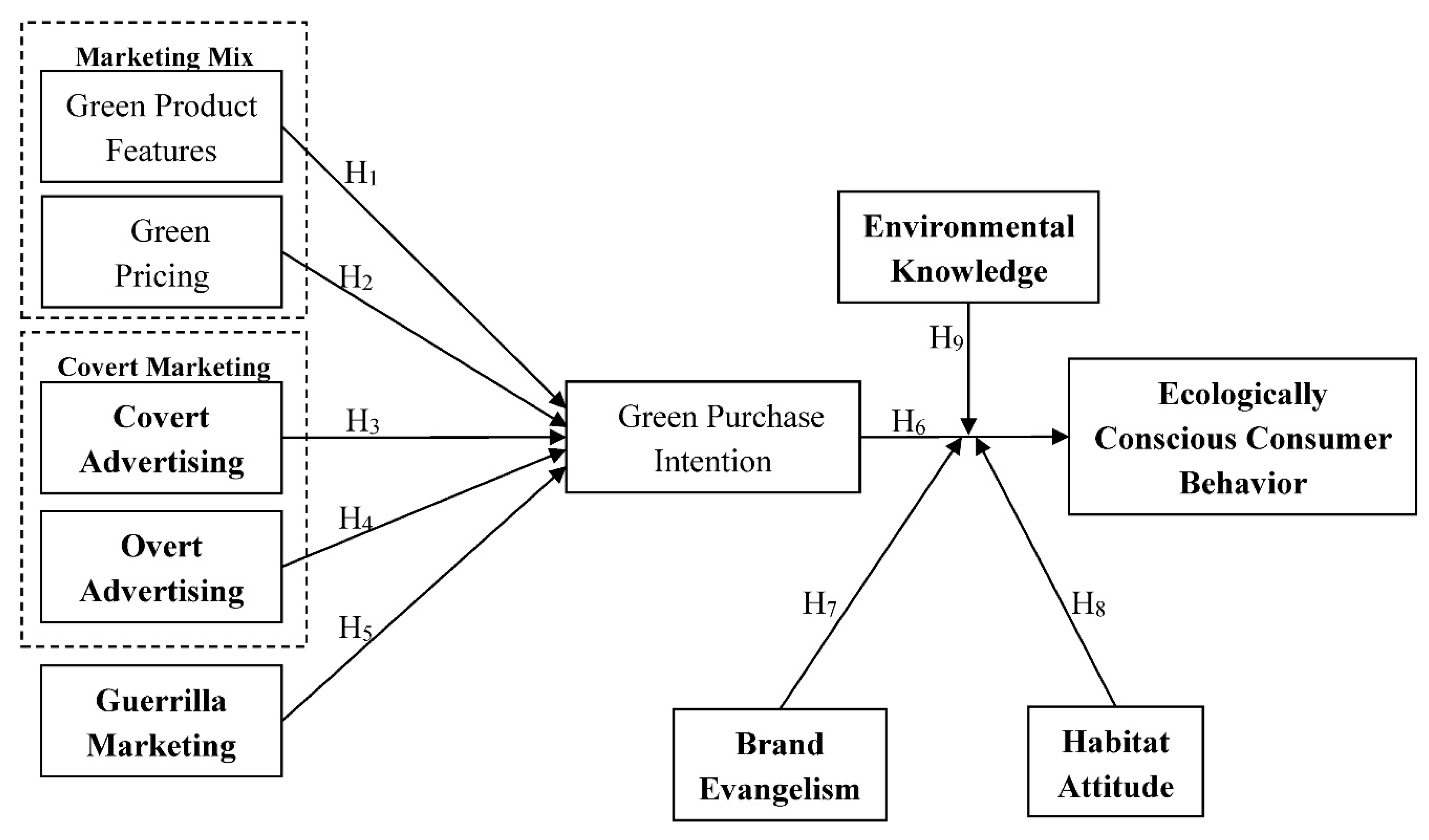

H1: Green product features have an impact on green purchase intention.

H2: Green price has an impact on green purchase intention.

Covert, Overt, Guerrilla Marketing and Purchase Intention

Covert, overt or other types of advertisements utilize the appearance and deliverability mechanisms of familiar non-advertising formats. Researchers across these marketing formats tried to cover them and sum them up as various forms of paid sponsored for their editorial content. Some manifested native marketing formats and product placement as the key component (Wojdynski & Evans, 2020). In this pandemic situation over the globe, numerous business entities have to face crucial circumstances while dealing with their business. A study regarding the SME sector of Greek also tried to cover a case study regarding various consequences of guerrilla marketing strategies instead of traditional marketing, suggest that this marketing type is also a vital factor in building positive, intentional factors (Gkarane, Efstratios-Marinos, Vassiliadis, & Vassiliadis, 2019). Another study (Talebpour & Khorsandi Fard, 2018) measured the differential effect of guerrilla and non-guerrilla marketing techniques on consumer perception. This differential effect was measured by showing a video advertisement at the time of questionnaire filling. Empirical findings revealed a significant difference between the control and experimental groups; the latter were shown specific guerrilla marketing ads of a brand.

Similarly, an exploratory study regarding guerrilla marketing for organic agricultural products was conducted, and penetration of fresh organic products was studied via guerrilla marketing as a novelty and unconventional approach (Damar-Ladkoo, 2016). The author collected responses from both supply and demand ends. The findings revealed that in this industry, reluctance seemed to consume fresh organic agricultural products, but promoting through unconventional guerrilla marketing appeared a beneficiary technique, which practitioners are ignoring. Some limited literature also discusses the impact of guerrilla marketing on awareness and perception of customers like, some earlier studies conducted, which uncover that guerrilla marketing is a multi-dimensional factor for change in brand equity, and it is also a vital element for building consumer perception (Mokhtari, 2011; Shakeel & Khan, 2011; Prevot, 2009). Literature also found empirical evidence exploring guerrilla marketing factors on behavioral building (Nawaz, et al., 2014). Recently, another study on Turkish consumers revealed that various dimensions of guerrilla marketing, i.e., surprise, novelty, aesthetics, clarity, emotional arousal, and relevance, significantly affect customer perception positively (Yildiz, 2017), on these bases present study hypothesized as:

H3: Covert advertising has an impact on green purchase intention.

H4: Overt advertising has an impact on green purchase intention.

H5: Guerrilla marketing has an impact on green purchase intention.

Purchase Intention and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior

Ecological behavior is now an emerging practical trend due to various health issues raised over the globe, especially while buying eatable products. Exploring the intentional factors for building ecological behavior of consumers, it was revealed that knowledge and consideration of health are the most important factors that arise intention, leading to ecological buying behavior, especially in the food sector of Asian countries (Paul & Rana, 2012). The literature on emerging economies was also studied regarding the increase in the importance of sustainable ecological conscious consumer behavior through various antecedents with the integration of theory of planned behavior, and found that along with environmental factors, green purchase intention is the key component that builds ecological behavior in consumer’s mindsets (Yarimoglu & Binboga, 2019).

Green buying or ecological buying behavior is generally a widely discussed and well-understood concept in literature. Recently, a study by Rausch and Kopplin (2021) provided a holistic framework to determine the key antecedents of buying behavior. They indicated that attitude towards sustained products has highly influenced the intention, which eventually builds ecological behavior in customers. Researchers also interrogate the relation between intention and ecological behavior through the theory of planned behavior in Mexican consumers, and found that along with control and other factors, the relationship between intention and ecological behavior is also significant (Müller, Acevedo-Duque, Müller, Kalia, & Mehmood, 2021).

Tseng and Chang (2015) also explored the antecedents and consequences for the intention to buy organic products. The study also found that while building ecological behavior, intention building is the critical factor marketers should keep in mind while developing their marketing terms (Tseng & Chang, 2015). Likewise, numerous studies have been conducted on the role of intention in building behavioral aspects in green marketing. The researchers uncover that along with other various attitudinal and environmental aspects, intention building is the most considerable behavioral factor regarding green ecological buying (Mataracı & Kurtuluş, 2020; Wang, Wang, Xue, Wang, & Li, 2018; Fong & Yazdanifard, 2014). So, the current study hypothesizes:

H6: Green purchase intention has an impact on ecologically conscious consumer behavior.

Moderation of Brand Evangelism, Habitat Attitude and Environmental Knowledge

Evangelism is now an emerging and eye catching trend in research and business world (Schnebelen & Bruhn, 2018; Nyffenegger, Krohmer, Hoyer, & Malaer, 2015). The recent research body has identified and discusses its emotional component but customer intention building needs to study. Literature also discusses this concept in various phenomena, like the relationship of hedonic utilitarian shopping values, brand evangelism and word-of-mouth. A research study by Al-Nawas, Altarifi and Ghantous (2021) found that instead of cognition, emotional aspects strongly influence brand evangelism, which is also higher than word-of-mouth. Linked to these findings, literature also supports that emotional bonding with brand eventually leads towards evangelism, even though some external factors try to bias the individual but it is the customer who chooses to be evangelist due to having a trustful bonding with the brand (Papista, Chrysochou, Krystallis, & Dimitriadis, 2018).

Various brands are considering evangelism marketing a vital tool during the pandemic COVID 19. A recent study (Panda, et al., 2020) also explored this phenomenon by integrating environmental factors with evangelism and the development of buying intention. The empirical findings prove that awareness of sustainability positively influences brand evangelism, which is positively linked with the purchase intention of green-tagged brands. Some other studies empirically prove that brand evangelism is the strongest and significant factor for purchase intention, especially in green products in the context of developing economies (Badrinarayanan & Sierra, 2018; Li, et al., 2020).

Attitudinal factors are also considered vital components of building intention. An investigation was aimed to explore the stimulus organism response model to evaluate attitude toward buying intention for organic food customers (Sultan, Wong, & Azam, 2021). The study empirically justified that besides gender differences, there is a significant relationship between attitudinal factors and intention building. Green and ecological buying behavior are well-discussed terminologies; literature also provides empirical findings regarding attitudinal factors indicating that attitude toward sustained products highly influences intention (Sun & Liang, 2020; Rausch & Kopplin, 2021). The researchers provided empirical findings that discussed attitude as the important factor for intention building, especially green products (Wang, Wong, & Alagas, 2020).

Environmental management is also an emerging trend in research. A study about sustainable ecological conscious consumer behavior through various antecedents in some emerging economies found the environmental consideration and related factors as the most vital components to drive the ecological behavior of consumers (Yarimoglu & Binboga, 2019). Literature also explored well that environmental knowledge and being conscious in human actions are the factors for behaviour building (Goh & Balaji, 2016). Similarly, a study in the context of UK consumers assures the significant consideration of environmental factors in their mindset, especially while paying for eatable products (Dunne & Siettou, 2020). Under the pandemic situation and increasing trends in environmental consideration, customers had developed a positive attitude toward reducing the adverse environmental effect of their product buying and consumption (Cheung & To, 2019; Chen, Hung, Wang, Huang, & Liao, 2017).

Moreover, substantial empirical research also discusses environment knowledge as a cognitive component in forming attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Jaiswal & Kant, 2018). Knowledge is also considered an enabler for different attributes regarding negative or positive impact on the environment due to their specific product usage. Literature on green marketing and buying behavior also directed the researchers to consider environmental, evangelism, and attitudinal factors in behavioral building (Sun, Su, Guo, & Tian, 2021; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020; Karunarathna, Bandara, Silva, & De Mel, 2020). Based on these arguments, we hypothesize:

H7: Brand evangelism moderates the relationship between green purchase intention and ecologically conscious consumer behavior.

H8: Habitat attitude moderates the relationship between green purchase intention and ecologically conscious consumer behavior.

H9: Environmental knowledge moderates the relationship between green purchase intention and ecologically conscious consumer behavior.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework

Methodology

Participants and Procedure

Covert, Overt and Guerrilla marketing are considerable tactics used by marketers nowadays. The study used these novel concepts, under-studied in existing literature, so the present study results add substantial knowledge to the literature by providing empirical results regarding the proposed model. The present study has used quantitative research type and primary data to evaluate the influence of these marketing mix tactics. The target population of the study is the consumer of the frozen food sector of Pakistan. Due to the vast, diverse population, and unavailability of a sampling frame, the study used non-probability public intercept sampling by targeting a sample size of 1000 respondents. From this sample, the valid completely filled number of questionnaires was 568, which shows that response rate of study is also higher than 90%. Now about instrument, firstly some questions were asked for their demographics, including gender, age, pre-visit, occupation, income, and preferred brand (Shown in

Table 2). Here a screening question was also considered regarding knowledge of covert marketing to have a real time valid responses data set. These demographic results uncover that the data is more male dominated by having maximum respondents of 25 to 34 year age frequent well educated buyers. Lastly these results also disclosed that K&N's and Sabroso are top of the list brand having maximum responses for these brands.

Both online and offline means were used for the data collection process rapidly and accurately. In the case of online data collection, a covert marketing example was shown at the top of the questionnaire. Whereas for offline data collection, a group of individuals at a specific space like college or university class was selected to show them a small video regarding the covert advertisement to create a real-time scenario for getting accurate responses.

CMV could be a useful technique when the data is being collected at a single time through a single questionnaire. It is also used where the constructs are having overemphasized association between them. There are numerous sources of measuring CMV like, scale or item complexity, respondent’s inability or unexperienced, having double-barreled item, respondent’s low involvement in research, positions of scale items, etc. As the consequence of CMV use, this enrich the reliability and convergent validity of in the research. It was seemed that researcher can deal with CMV into two ways, i.e. procedural remedies and use of statistical techniques. Researcher used procedural remedies at the initial stage of designing the questionnaire to overcome the CMV. Common procedural remedies might be including the use of more than one source of information to collect the data for a specific construct of a model. Authors also use procedural remedies to shows the potential impact of common method variance in their findings. In other words, they might be facing some problems in findings justification which was full filled through some procedural solutions. In all these situations, they are more inclined to use statistical treatments for those problems. So, there is a wide range of statistical techniques which are used by numerous researchers to overcome the CMV. The most considerable are Harman's single factor test as the Common Latent Factor (CLF) and second one was CFA for a single factor (Ali et al., 2021). This Harman's single factor test is also known as Harman's one factor test which is most popular technique used in model evaluation (Ashfaq et al., 2020). By following this technique, all 48 adopted items in present research were put into single confirmatory factor analysis. So, the findings of this analysis also verify that there is no existence of CMV bias in sample data.

Measures

Frozen food was selected as a target product category for the study to measure the integrated model of the marketing mix, covert marketing attitudinal, environmental aspects, and ecological behaviors. Therefore, items were identified from various studies regarding these concepts after an extensive literature review. All the respective items were measured through a five-point Likert scale. Green marketing mix was measured through the four-item scale of green product feature (Mahmoud, Ibrahim, Ali, & Bleady, 2017), and green pricing was assessed through 4 items (Suki, 2016). An eight-item scale was used to measure covert advertisement (Kelly, 2015), while the overt advertisement was measured through a four-item scale by Zhang (2020). Likewise, a seven-item scale was used to measure guerrilla marketing (Bradley, 2007). Purchase intention and environmentally conscious consumer behavior were measured through eight items by Soon and Kong (2012) and Zabkar & Hosta (2013). Lastly, moderating variables of three concepts was also measured: environmental knowledge was measured through a three-item scale by Mahmoud et al. (2017), brand evangelism was assessed through a five-item scale (Matzler, Pichler, & Hemetsberger, 2007), and four items were adopted to measure habitat attitude towards the brand (Saupi, Harun, Othman, Ali, & Ismael, 2019).

Data Analysis and Results

Descriptive

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics, which shows that the valid sample size was 568 responses. The mean and standard deviation, which show the average and deviance of all variables, indicate above midpoint level and less scattered behavior of the data. Lastly, the table shows the skewness and kurtosis, which are used to analyze the symmetry in the dataset. Its value less than ±1.00 shows normally skewed (Hair et al., 2014); here, the BE and EK have slightly high values.

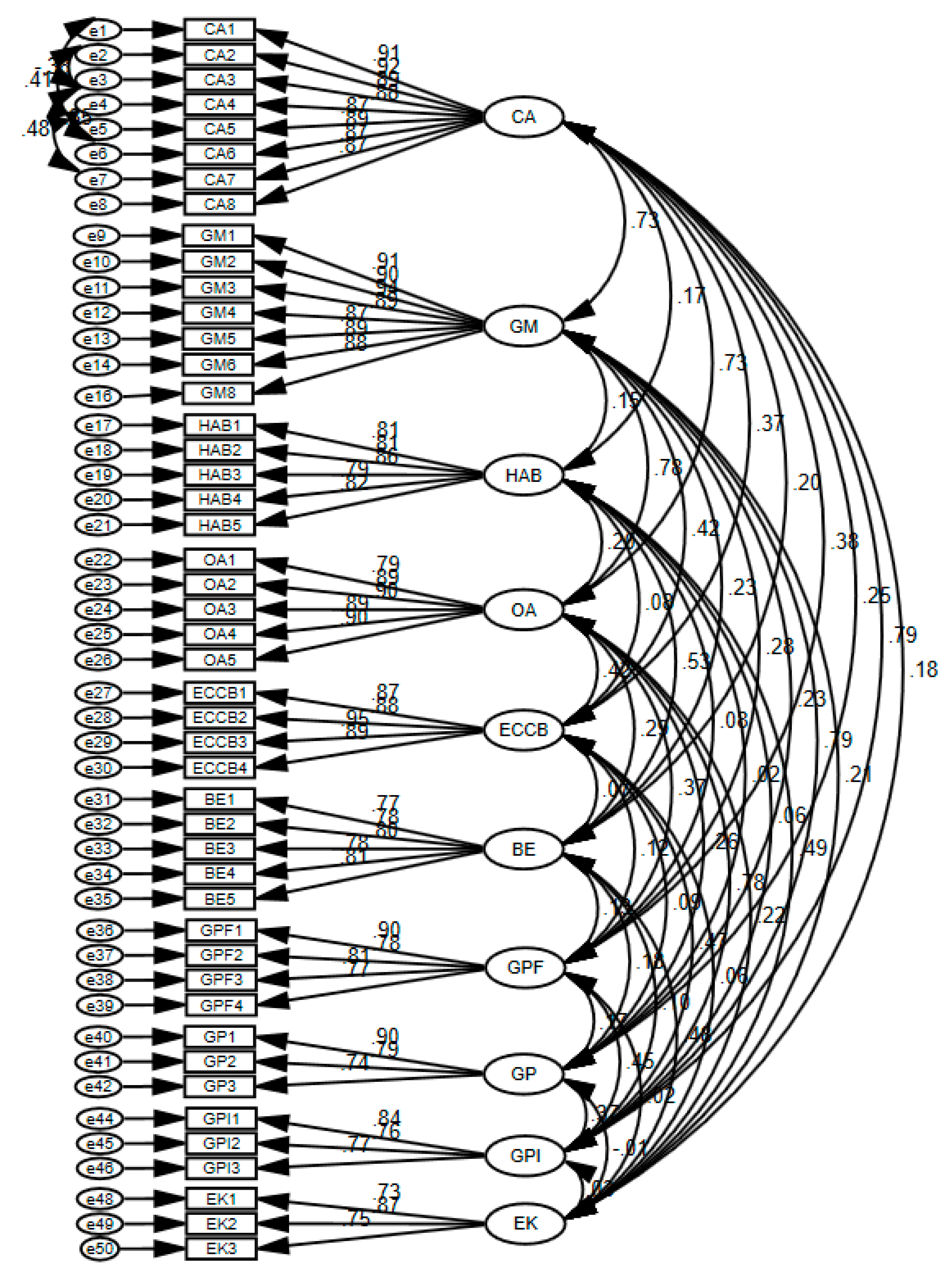

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Testing the integrated model empirically by targeting the customers of the food sector to measure their buying behavior regarding green marketing is the key step of the study. The present study used the covariance-based structural equation model (SEM) applied through AMOS software to extract the quantitative findings from collected data (Hair et al., 2017). SEM is the state-of-the-art technique to measure the inner and outer model of a research framework, which allows the relation of different concepts in one model (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Kline, 2005).

Some other well-known criteria for the goodness of fit for the model are RMR, GFI, AGFI, PGFI and SRMR criteria. From all these, mainly SRMR is considered as standardized difference between observed and predicted correction for this, goodness is that value should be less than 0.08 (Hair, Gabriel, & Patel, 2014). In present research value for SRMR goodness was 0.0313, which is well enough to meet the goodness criteria. Moreover, numerous researchers have done quality work regarding running measurement models to access reliability and two main types of validity, i.e., convergent and discriminant validity. Firstly, the reliability test shows the internal consistency of data collected through any specific research instrument. The present research is measured through composite reliability, which is preferable for reliability checks (Hair et al., 2019). Next, validity measures the extent of measurability of the instrument for that specific concept or variable. There are two types of validity: convergent and discriminant. First, convergent validity relates to the convergence of items and variables of a framework measured through two sub-criteria. It is assessed through factor loading values, which show that an item is a good measure for a variable whose value should be greater than 0.6. Three items did not meet the criteria in our study, and we omitted those questions for further analysis (Appendix 1 & 2). The convergent validity is also computed through average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in

Table 4. Our results demonstrate convergent validity because AVE values are higher than 0.5 for each construct (Hair et al., 2019).

On the other hand, discriminant validity talks about the theoretical difference between the variables and items. It is measured through the Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT, but the first two are considered the most vital tool for measurement. The results meet the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which states that square roots of AVE values of each construct (placed in diagonal) should be greater than the inter-construct correlations, as shown in

Table 4. In addition, the table also justifies the values of maximum shared variance (MSV) parallel to comparison with AVE, the criteira for this is that value of MSV should be less than the value of AVE for each constrct in present research all the values are well lesser which support the concept of disriminent validity.

Discriminant validity is also assessed through the Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) Ratio. Hair et al. (2018) recommend that its value should be less than 0.9, especially while talking about the inter-correlation of variables (

Table 5).

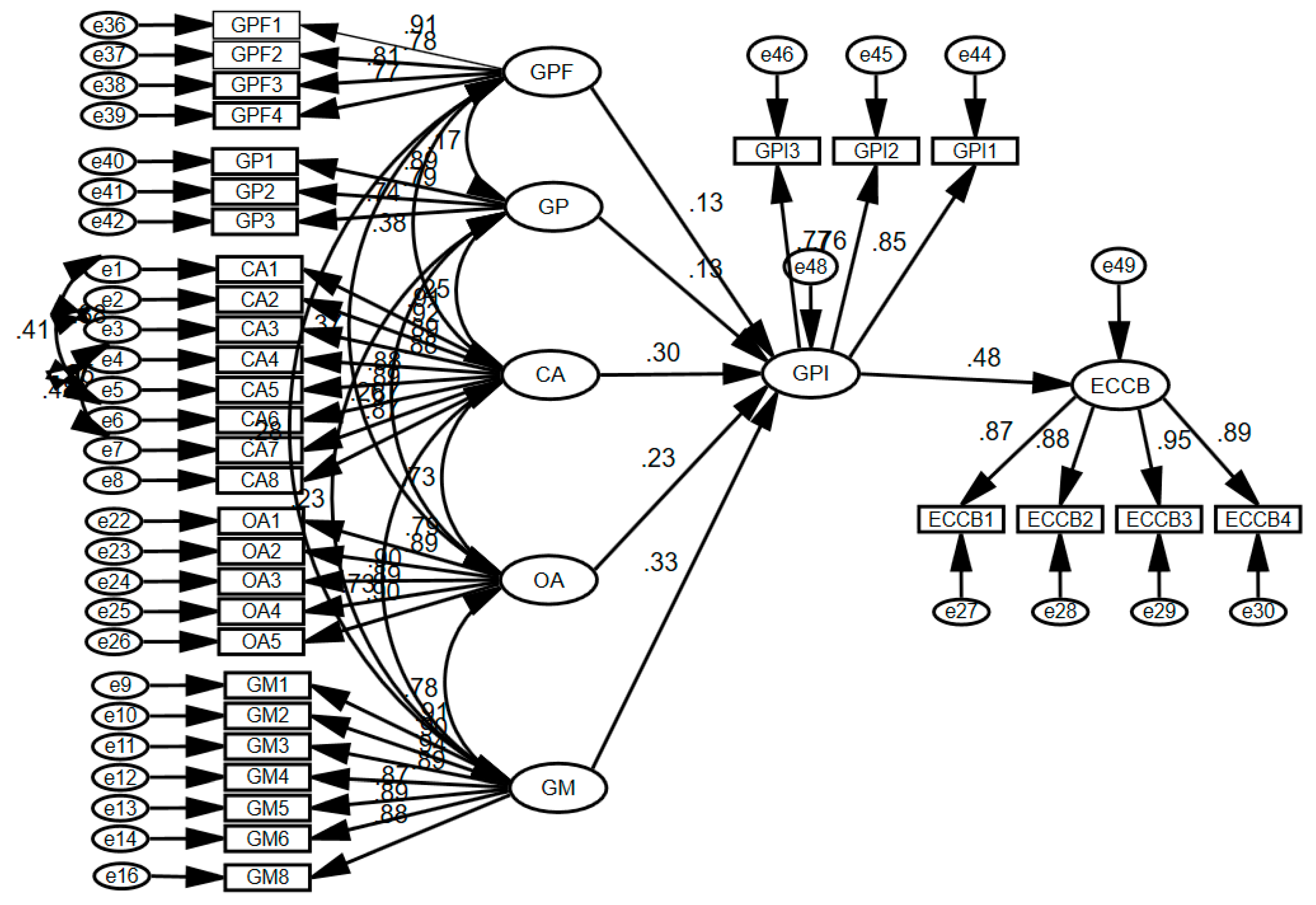

Path Analysis

After the testing goodness of model and validation, further valuable process is to analyze the path model through SEM in AMOS. This shows the results of the outer model, which tells about the direction and strength of the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables. Error terms are also shown on each construct, as well as an indicator.

Figure 2 demonstrates the results of path model analysis. It shows the influence of green marketing features, covert, overt and guerrilla advertisement on green purchase intention and ecologically conscious consumer behavior. Here, the estimation values represent the direction of relationships between exogenous and endogenous latent variables. The positive value represents that exogenous and endogenous latent variables have a positive direct relationship. Next, from this graphical representation, values for coefficients are shown in

Table 6 along with standard error (S.E.), critical ratio (CR= Estimate/S.E.) (Chang, Tsaur, Yen, & Lai, 2020; Ali, Mahmood, Ahmad, & Ikram, 2021).

The significant values of the paths are determined through critical ratio (C.R.) and p values. The results in

Table 6 show that all the direct hypotheses, i.e., H1 to H6, are considerably and positively significant (C.R.>1.96).

The moderation in the model plays a valuable strengthening or weakening role for any relationship. The present study also interrogates three moderators, i.e., Brand Evangelism, Environmental Knowledge and Habitat Attitude, as shown in

Table 7.

These results show that all three moderators are significant, but mainly brand evangelism and environmental knowledge play a valuable role in strengthening the relationship at a significant level of p-value less than 0.05.

Table 7 also shows the results of the significance test of moderators with the help of t and p values. The table is being segregated into three portions. Firstly, it shows a moderation of brand evangelism

H7. Its coefficient value is .2410 and the t-value is 4.1625 at 95% confidence level means that brand evangelism strengthens the relationship. Next, habitat attitude

H8 is also being studied as moderator with a coefficient of .0230 also showing positive impacts but the t-value is 0.3325 and p-value is also not accepted, which means that habitat attitude moderates the relationship but not the relationship founded significant. Lastly,

H9 is for the moderation of the environmental knowledge, which has the coefficient of .2619, with a t value of 4.1108 and p-value< .001, meaning that it strengthens the relationship so this relationship was also found to be significant. Summing up all these findings, the relationship between purchase intention and ecological conscious buying behavior is significantly and strongly moderated by environmental knowledge and brand evangelism.

Discussion

The core purpose of this research was to measure the influence of various marketing tactics, including covet, overt and guerrilla, on intention and ecological buying behavior of frozen food in a developing economy, i.e., Pakistan. Drawing a gap from the existing literature, the current study developed an integrated model with various marketing tactics that are vital as intention-building factors. Empirical findings extracted through a distinctive methodology uncover that these marketing tactics play a valuable role in developing an individual’s intention. It also seems that people’s perception is changing, and their intention-building factors also switch toward novel marketing tactics. The results also disclosed that instead of conventional green marketing tactics, covert and guerrilla marketing are more strong antecedents for developing customer's intention, which was also an identified gap in the literature (Serazio, 2021; Evans & Wojdynski, 2020). These results show that these marketing tactics lead to customer intention, which eventually builds the ecological behaviour of consumers, especially while buying frozen food (Zhang, 2020; Wojdynski & Evans, 2020; Rosenbaum, Ramirez, & Kim, 2021).

Coming toward the moderators, the study interrogates three different moderations, and the results are also justifiable. All three variables, i.e., Brand Evangelism, Environmental Knowledge and Habitat Attitude, significantly strengthen intention and ecological behaviour factors, but evangelism and environmental knowledge are found stronger than the third one. Summing up all these findings, it shows that a higher level of evangelism for the brand and good environmental knowledge results in a high level of ecological buying behaviour in consumers, especially in dealing with eatable products. The results are coherently consistent with the existing literature (Badrinarayanan & Sierra, 2018; Li, et al., 2020; Dunne & Siettou, 2020), whereas some identified gaps are also bridged by the present findings (Sun, Su, Guo, & Tian, 2021; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020; Karunarathna, Bandara, Silva, & De Mel, 2020). These findings direct practitioners to move from traditional marketing tactics towards novel covert or overt marketing techniques. All these substantial findings are building a logically grounded bridge between theory and practice. These findings will also uplift the understanding level regarding theory and practicability, especially while dealing with customer attraction tactics.

Theoretical Implications

The first theoretical contribution of this research is that research explored well positive impact of various marketing tactics in building green purchase intention. These findings are consistent with the existing literature. Radically, green or environmentally friendly products should also consider GPF and GP as intention building factors because, specifically in developing countries, price consideration for any product is also a vital factor for intention building, as documented in the existing literature (Liana & Oktafani, 2020; Karunarathna, Bandara, Silva, & De Mel, 2020; Sembiring, 2021; Gustavo Jr, et al., 2021). These findings also enrich the literature regarding the significant positive influence of GPF and GP for purchase intention. The present study also relatedly responds to the call of researchers regarding the paucity of literature for covert, overt and guerrilla marketing (Serazio, 2021; Evans & Wojdynski, 2020). Departing from prior studies, this research has found an integrated model for these new marketing tactics and marketing mix. So, this study also fills the knowledge gap directing the positive influence of these factors for intention building, which eventually a significant factor for ECCB

Some other theoretical contribution is regarding consideration of moderators, and approve that BE and EK are the factors that strengthen the positive relationship of PI and ECCB. These findings also fill the theoretical gap in the existing literature regarding the dearth of literature for moderations of these variables (Sun, Su, Guo, & Tian, 2021; Musa, Mansor, & Musa, 2020). The results affirm that theory developers should consider these aspects as well, which were underpinned. Last but not least, the methodological implications adopted in the study to consider both online and offline means of data collection, and secondly study also used a visual approach for showing covert ads to respondents to have an accurate response from them. Summing up all these, the present research redirects scholars to underscore the positive implications of these attractive new marketing tactics parallel to the existing approaches.

Practical Implications

Beyond the theoretical aspects, the study also directs some implications for practitioners in two major aspects. Firstly, it requires that managers should consider and highlight the product's price and features while developing and marketing the product through some novel marketing tactics. The provided information under the study is clear and instructs practitioners to play their role in product development while launching the product in the market. Findings also found for practitioners that although feature and price are essential factors while marketing a product than the way of marketing the product. In the competitive business world, you have to do something different to capture customers; these covert, overt or guerrilla marketing tactics are those differentiators.

Secondly, strategical findings of the present study regarding moderation of BE, EK, and HAB on intention and behaviour building could also serve as a solution for some fundamental issues in the business. Nowadays, positive word of mouth is an important factor for marketers. If a satisfied customer represents the brand as an evangelist for the brand, that will positively influence the product. So, practitioners should consider these findings that BE and EK are valuable factors for strengthening intention and ecologically conscious behavior. However, all these results should be interpreted practically with caution, in that these results depend upon objectivity. Practitioners should also consider some factors to enhance environmental consideration knowledge.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite all these theoretical and practical contributions, the present study has enlightened some future directions for researchers. Although the present study is based on some theoretical gaps directed in the existing literature, some time and resource constraints could be considered as future directions. Firstly, the study used price and features from the marketing mix but the remaining P's of the marketing mix, i.e., place and promotion, were omitted. Therefore, future researchers can use those marketing mix tactics as well. It might be possible that some other factors exist, which potentially may act as intention-building factors.

The study also considered moderation but integrated mediated moderation of the model was not incorporated. So, the study urges future researchers to consider the mediated moderation test on this comprehensive model. Lastly, about the theoretical aspect, some other factors were neglected in the present study that could be strong influencers for intention building and explore some post-purchase consequences like loyalty and repurchase inetenion that could provide a beneficiary result for the assurance of this model. Another theoretical direction is that future studies should also measure the post-purchase behavior, and mediation of individual personality to measure how customer personality plays a role in buying green products.

The study is also limited to the frozen food industry, but future researchers can also cover other sectors that use covert or overt marketing techniques to measure the goodness of those tactics for them. Demographically, whether the study covers different cities of Pakistan as developing countries, but some other countries or a cross-country comparison should also be made with this model. Next, as discussed, the present study used both means of data collection, i.e., online and offline, but did not measure the differential effect between these two datasets, which could also be a theoretical finding that which means of data is more accurate. Parallel to these limitations, methodological limitations are also under consideration. As the present study used non-probability sampling for the experimental study, future researchers should consider a longitudinal probability-based survey to evaluate pre and post-perception of respondents after watching these covert and overt advertisements. Thus, researchers are recommended to conduct some research to have some nuanced examination and consider all these limitations in future models.

Conclusion

The present study tried well to bridge the unaddressed theoretical as well as practical gaps in the sector and literature. Concrete findings robust the conclusion with some sufficient warranted evidence generated through distinctive methodological aspects. The present research contributes to the burgeoning stream of marketing literature by theoretically and empirically testing the marketing mix and covert marketing tactics to build environmentally conscious behavior for green products. Findings indicate that instead of conventional marketing mix tactics, covert marketing tactics are the valuable factors for intention building. Moreover, findings also emphasize that evangelism and environmental knowledge are significant motivators to build the conscious ecological behavior of customers of the frozen food industry in developing countries. The findings are in line with the previous results (Chang, Chen, Yeh, & Li, 2021; Wojdynski & Evans, 2020; Müller, Acevedo-Duque, Müller, Kalia, & Mehmood, 2021; Sultan, Wong, & Azam, 2021). The researchers are recommended to extend the study by incorporating shortcomings of the present investigation, as discussed in the limitations section.

Appendix 1. Path Analysis Graph (After 3 Items Deletion Here Onwards)

Appendix 2. Factor Loadings and Reliability

| Factors |

Loadings |

Reliability |

Factors |

Loadings |

Reliability |

| GPF1 |

0.905 |

0.891 |

GM1 |

0.907 |

0.966 |

| GPF2 |

0.784 |

GM2 |

0.896 |

| GPF3 |

0.814 |

GM3 |

0.938 |

| GPF4 |

0.773 |

GM4 |

0.886 |

| GP1 |

0.895 |

0.852 |

GM5 |

0.865 |

| GP2 |

0.794 |

GM6 |

0.894 |

| GP3 |

0.737 |

GM8 |

0.881 |

| CA1 |

0.909 |

0.967 |

ECCB1 |

0.870 |

0.943 |

| CA2 |

0.918 |

ECCB2 |

0.879 |

| CA3 |

0.886 |

ECCB3 |

0.949 |

| CA4 |

0.881 |

ECCB4 |

0.889 |

| CA5 |

0.875 |

EK1 |

0.731 |

0.830 |

| CA6 |

0.888 |

EK2 |

0.871 |

| CA7 |

0.871 |

EK3 |

0.753 |

| CA8 |

0.868 |

BE1 |

0.768 |

0.890 |

| OA1 |

0.787 |

0.943 |

BE2 |

0.775 |

| OA2 |

0.892 |

BE3 |

0.803 |

| OA3 |

0.903 |

BE4 |

0.778 |

| OA4 |

0.893 |

BE5 |

0.806 |

| OA5 |

0.901 |

HAB1 |

0.811 |

0.909 |

| GPI1 |

0.845 |

0.836 |

HAB2 |

0.805 |

| GPI2 |

0.762 |

HAB3 |

0.858 |

| GPI3 |

0.770 |

HAB4 |

0.788 |

| |

|

|

HAB5 |

0.816 |

References

- Al Nawas, I.; Altarifi, S.; Ghantous, N. E-retailer cognitive and emotional relationship quality: their experiential antecedents and differential impact on brand evangelism. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 1249–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Mahmood, A.; Ahmad, A.; Ikram, A. Humor of the Leader: A Source of Creativity of Employees Through Psychological Empowerment or Unethical Behavior Through Perceived Power? The Role of Self-Deprecating Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegro, R.; Calagna, A.; Monaco, D.L.; Ciprì, V.; Bongiorno, C.; Cammilleri, G.; Battaglia, L.; Sadok, S.; Benfante, V.; Tliba, I.; et al. The assessment of the attitude of Sicilian consumers towards wild and farmed seafood products – a sample survey. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2506–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A., Harun, A., & Hussein, Z. (2012). The influence of Environmental Knowledge and Concern on Green Purchase Intention the role of Attitude as a Mediating Variable. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 7(2), 145-167.

- Amoako, G. K. , Dzogbenuku, R. K., & Abubakari, A. (2020). Do Green Knowledge and Attitude influence the youth's Green Purchasing? Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(8), 1609-1626.

- Anastasiou, K.; Miller, M.; Dickinson, K. The relationship between food label use and dietary intake in adults: A systematic review. Appetite 2019, 138, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Sierra, J.J. Triggering and tempering brand advocacy by frontline employees: vendor and customer-related influences. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaeva, Z.; Rudawska, E.D.; Lopatkova, Y. Sustainable business model in food and beverage industry – a case of Western and Central and Eastern European countries. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1573–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, N. Book Review: Guerrilla Marketing Research: Marketing Research Techniques that can help any business make more money. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 49, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, G.A.; Osborne, L.; Mewburn, I.; Crowther, P. Guerrillas in the [Urban] Midst: Developing and Using Creative Research Methods—Guerrilla Research Tactics. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.; Warin, L. Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Obes. Rev. 2015, 17, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. Y. , Tsaur, S. H., Yen, C. H., & Lai, H. R. (2020). Tour member fit and tour member–leader fit on group package tours: Influences on tourists’ positive emotions, rapport, and satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour.Manag., 42, 235–243.

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-S.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Li, H.-X. Sustainable consumption models for customers: investigating the significant antecedents of green purchase behavior from the perspective of information asymmetry. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 64, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B. , Wafa, S. A., Igau, O. A., Chekima, S., & Sondoh Jr, S. L. (2016). Examining Green Consumerism Motivational Drivers: Does Premium Price and Demographics Matter to Green Purchasing? Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 3436-3450.

- Chen, Y.-S.; Hung, S.-T.; Wang, T.-Y.; Huang, A.-F.; Liao, Y.-W. The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.; To, W. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullington, H.E.; Zeng, F.-G. Comparison of Bimodal and Bilateral Cochlear Implant Users on Speech Recognition With Competing Talker, Music Perception, Affective Prosody Discrimination, and Talker Identification. Ear Hear. 2011, 32, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damar-Ladkoo, A. Guerilla Marketing of Fresh Organic Agricultural Products. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 06, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, W. W. , Avicenna, F., & Meideline, M. M. (2020). Purchase Intention of Green Products Following an Environmentally Friendly Marketing Campaign: Results of a Survey of Instagram Followers of InnisfreeIndonesia. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research, 8(2), 160-177.

- Dinh, T. D. , & Mai, K. N. (2015). Guerrilla Marketing’S effects on Gen Y’s word-of-mouth intention–a mediation of Credibility. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28(1), 4–22.

- Dunne, C.; Siettou, C. UK consumers' willingness to pay for laying hen welfare. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Wojdynski, B. An introduction to the special issue on native and covert advertising formats. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzan, N. , & Azhar, F. N. (2019). The influence of Environmental Concern and Environmental Attitude on Purchase Intention towards Green Products: A case study of students college in Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. In International Conference on Public Organization (ICONPO).

- Fong, K. , & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). The review of the two latest marketing techniques; viral marketing and guerrilla marketing which influence online consumer behavior. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 14(2), 1–4.

- Gaidhani, S., Arora, L., & Sharma, B. K. (2019). Understanding the attitude of generation Z towards workplace. International Journal of Management, Technology and Engineering, 9(1), 2804-2812.

- Gkarane, S. , Efstratios-Marinos, L., Vassiliadis, C. A., & Vassiliadis, Y. (2019). Combining Traditional and Digital Tools in Developing an International Guerilla Marketing Strategy: The Case of a SME Greek Company. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism (pp. 397-404). Cham: Springer.

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M. Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökerik, M.; Gürbüz, A.; Erkan, I.; Mogaji, E.; Sap, S. Surprise me with your ads! The impacts of guerrilla marketing in social media on brand image. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 1222–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavo Jr, J. U. , Trento, L. R., de Souza, M., Pereira, G. M., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B., Ndubisi, N. O.,... Zvirtes, L. (2021). Green Marketing in Supermarkets: Conventional and Digitized Marketing alternatives to reduce waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 296, 126531.

- Hair, J. F. , Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its Application as a Marketing Research Tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2).

- Harrigan, P. , Roy, S. K., & Chen, T. (2020). Do Value Co-creation and Engagement Drive Brand Evangelism? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(3), 345-360.

- Hashem, T. N. , & Al-Rifai, N. A. (2011). The influence of applying Green Marketing Mix by Chemical Industries Companies in three Arab States in West Asia on Consumer'S Mental Image. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(3), 92-101.

- Hayat, K. , Nadeem, A., & Jan, S. (2019). THE IMPACT OF GREEN MARKETING MIX ON GREEN BUYING BEHAVIOR:(A CASE OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA EVIDENCE FROM THE CUSTOMERS). City University Research Journal, 9(1), 27-40.

- Hsu, L. C. (2019). Investigating the Brand Evangelism effect of Community Fans on Social Networking Sites: Perspectives on Value Congruity. Online Information Review, 43(5), 842-866.

- Huang, Y.-C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.-C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. , & Patel, B. (2020). Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Consumer’s Purchase Intention in Consumer Durable Industry: A Study of Gujarat State. UGC Care Group I Listed Journal, 10(7), 265-274.

- Junaedi, M. S. (2015). Pengaruh kesadaran lingkungan pada niat beli produk hijau: Studi perilaku konsumen berwawasan lingkungan. Benefit: Jurnal Manajemen dan Bisnis, 9(2), 189-201.

- Kartawinata, B. R., Maharani, D., Pradana, M., & Amani, H. M. (2020). The Role of Customer Attitude in Mediating the Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Green Product Purchase Intention in Love Beauty and Planet Products in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 1, pp. 3023-3033.

- Karunarathna, A. K. , Bandara, V. K., Silva, A. S., & De Mel, W. D. (2020). Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Customers’ Green Purchasing Intention with Special Reference to Sri Lankan Supermarkets. South Asian Journal, 1(1), 127-153.

- Kelly, C. (2015). To explore if guerrilla marketing campaigns effect consumption behaviour on consumers between the ages of 18-29, Generation Y.

- Kiran, V. , Majumdar, M., & Kishore, K. (2012). Marketing the viral way: a strategic approach to the new era of marketing. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research, 1(3), 1-5.

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, G. Does environmentally responsible purchase intention matter for consumers? A predictive sustainable model developed through an empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 58, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , Inzamam, U. H., Hira, N., Gadah, A., Wedad, A., Ahsan, N., & Javaria, H. (2020). How Environmental Awareness relates to Green Purchase Intentions can affect Brand Evangelism? Altruism and Environmental Consciousness as Mediators. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(5), 811-825.

- Liana, W. , & Oktafani, F. (2020). The Effect of Green Marketing and Brand Image Toward Purchase Decision on the Face Shop Bandung. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR), 4(4).

- Lu, S.; Chen, G. (.; Wang, K. Overt or covert? Effect of different digital nudging on consumers’ customization choices. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2020, 12, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, T. O. (2018). Impact of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 5(2), 127-135.

- Mahmoud, T.O.; Ibrahim, S.B.; Ali, A.H.; Bleady, A. The Influence of Green Marketing Mix on Purchase Intention: The Mediation Role of Environmental Knowledge. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2017, 8, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, D.K.Z.A.; Hanan, S.A.; Hassan, H. A mediator of consumers' willingness to pay for halal logistics. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataracı, P.; Kurtuluş, S. Sustainable marketing: The effects of environmental consciousness, lifestyle and involvement degree on environmentally friendly purchasing behavior. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2020, 30, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K. , Pichler, E. A., & Hemetsberger, A. (2007). Who is spreading the word? The Positive influence of Extraversion on Consumer Passion and Brand Evangelism. Marketing Theory and Applications, 18(1), 25-32.

- Mehran, M.M.; Kashmiri, T.; Pasha, A.T. Effects of Brand Trust, Brand Identification and Quality of Service on Brand Evangelism: A Study of Restaurants in Multan. J. Arab. Crop. Mark. 2020, 2, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melović, B.; Cirović, D.; Backovic-Vulić, T.; Dudić, B.; Gubiniova, K. Attracting Green Consumers as a Basis for Creating Sustainable Marketing Strategy on the Organic Market—Relevance for Sustainable Agriculture Business Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliore, G. , Thrassou, A., Crescimanno, M., Schifani, G., & Galati, A. (2020). Factors affecting consumer preferences for “natural wine”. British Food Journal, 122(8), 2463-2479.

- Mokhtari, M. A. (2011). Analysis of Brand Awareness and Guerilla Marketing in Iranian SME. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 4(1), 115-129.

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive Sustainability Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior Incorporating Ecological Conscience and Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, H., Mansor, N., & Musa, H. (2020). The Influence of Green Marketing Mix on Consumer Purchase Intention Towards Green Products. International Journal of Human and Technology Interaction (IJHaTI), 4(1), 89-94.

- Nawaz, A., Raheem, A., Areeb, J., Ghulam, M., Hira, S., & Rimsha, B. (2014). Impacts of Guerrilla Advertising on Consumer Buying Behavior. Information and Knowledge Management, 4(8), 45-52.

- Nielsen. (2018). Mercato Pubblicitario In Italia nel 2017. Retrieved from Available at: https://www.primaonline.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Nielsen_20180215_nota_adv_dicembre_def.pdf.

- Nur, F. , Akmaliah, N., Chairul, R., & Safira, S. (2021). Green purchase intention: The power of success in green marketing promotion. Management Science Letters, 11(5), 1607-1620.

- Nyffenegger, B. , Krohmer, H., Hoyer, W. D., & Malaer, L. (2015). Service brand relationship quality: hot or cold? Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 90-106.

- Panda, T. K. , Kumar, A., Jakhar, S., Luthra, S., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Kazancoglu, I., & Nayak, S. S. (2020). Social and Environmental Sustainability model on Consumers’ Altruism, Green Purchase Intention, Green Brand Loyalty and Evangelism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118575.

- Papista, E.; Chrysochou, P.; Krystallis, A.; Dimitriadis, S. Types of value and cost in consumer–green brands relationship and loyalty behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 17, E101–E113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rana, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroth, P. , Ritter, M. S., & Rueger-Muck, E. (2020). Online grocery shopping adoption: do personality traits matter? British Food Journal, 122(3), 957-975.

- Prakash, G.; Pathak, P. Intention to buy eco-friendly packaged products among young consumers of India: A study on developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevot, A. (2009). The Effects of Guerilla Marketing on Brand Equity. The Consortium Journal, 13(2), 33-40.

- Rabbanee, F.K.; Afroz, T.; Naser, M.M. Are consumers loyal to genetically modified food? Evidence from Australia. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riorini, S. V., & Widayati, C. C. (2016). Brand Relationship and its effect towards Brand Evangelism to Banking Service. International Research Journal of Business Studies, 8(1), 33-45.

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Ramirez, G.C.; Kim, K. (. From overt to covert: Exploring discrimination against homosexual consumers in retail stores. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 59, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudi, H. R. (2009). Pengaruh strategi green marketing terhadap pilihan konsumen melalui pendekatan marketing mix (Studi kasus pada The Body Shop Jakarta). (Doctoral dissertation, Program Pasca Sarjana Universitas Diponegoro).

- Sabir, R. I. , Sarwar, M. A., Rana, M. I., Zulfiqar, S., Akhtar, N., & Kamil, H. (2014). Impact of covert marketing on consumer buying behavior. International Review of Management and Business Research, 3(1).

- Sajjad, A.; Asmi, F.; Chu, J.; Anwar, M.A. Environmental concerns and switching toward electric vehicles: geographic and institutional perspectives. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39774–39785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]