Submitted:

13 October 2023

Posted:

16 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

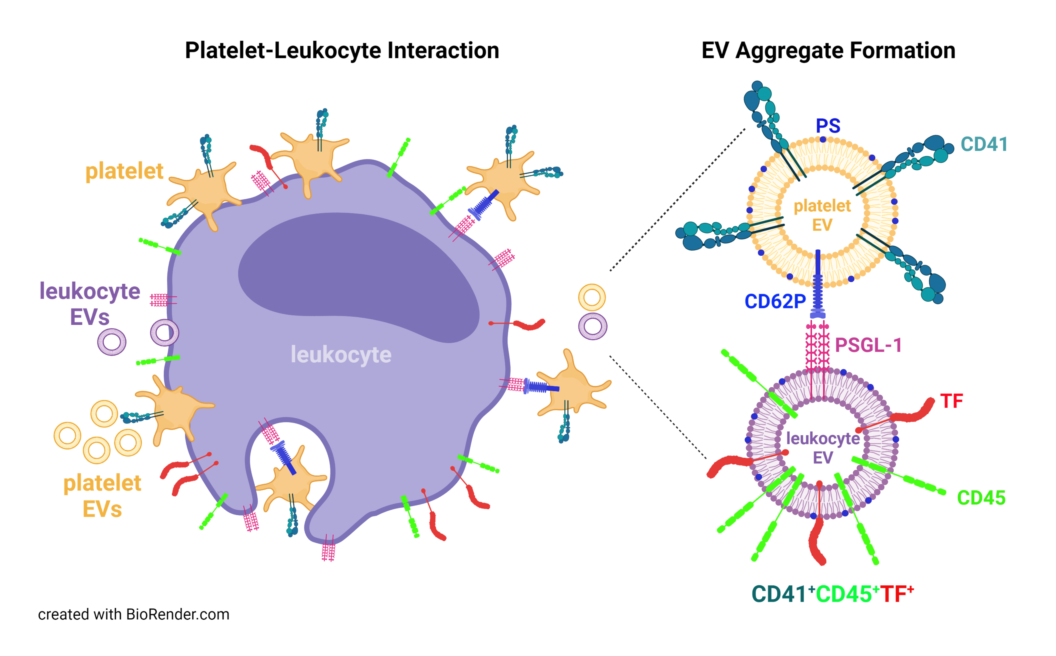

1. Introduction

2. Results

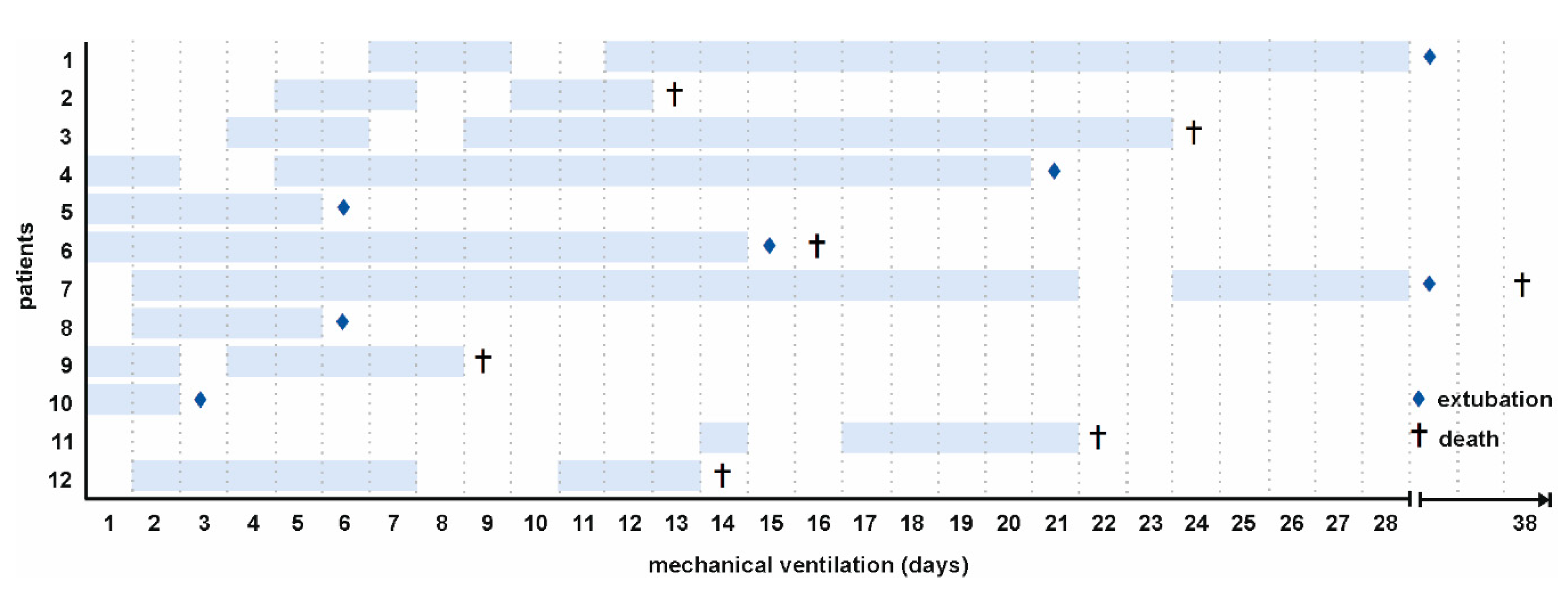

2.1. Patient Characteristics

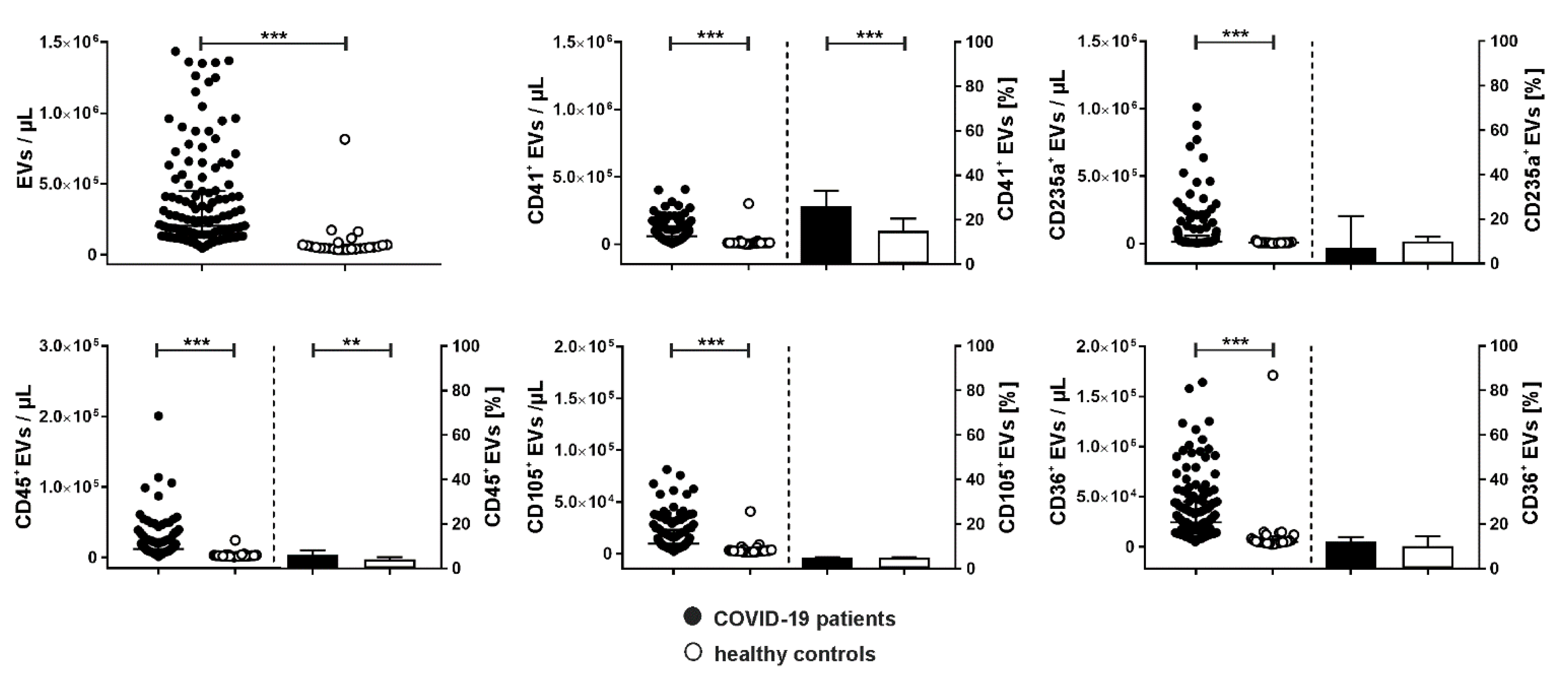

2.2. Cellular Origin of Extracellular Vesicles

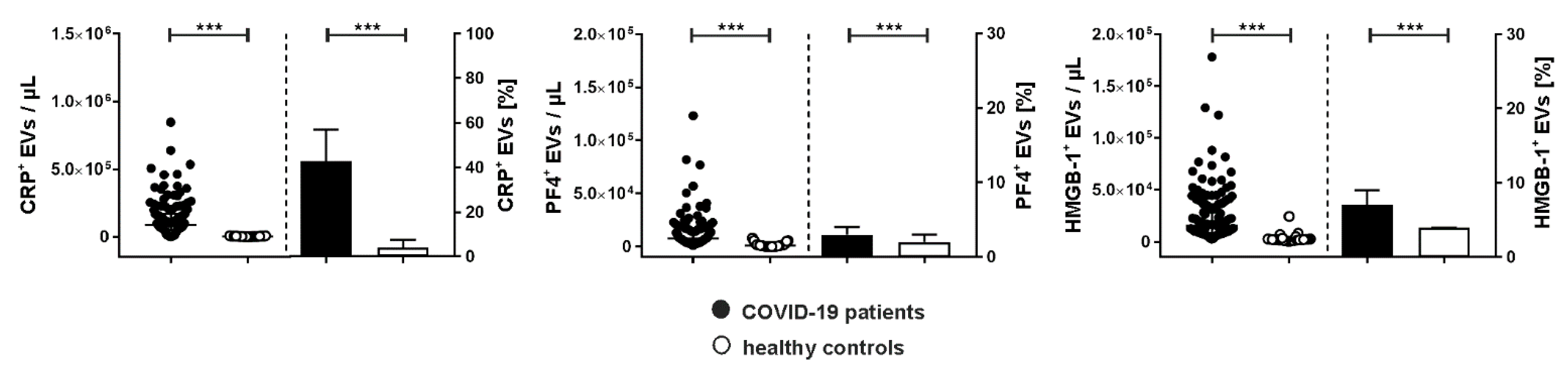

2.3. Association of Extracellular Vesicles with CRP, PF4, and HMGB-1

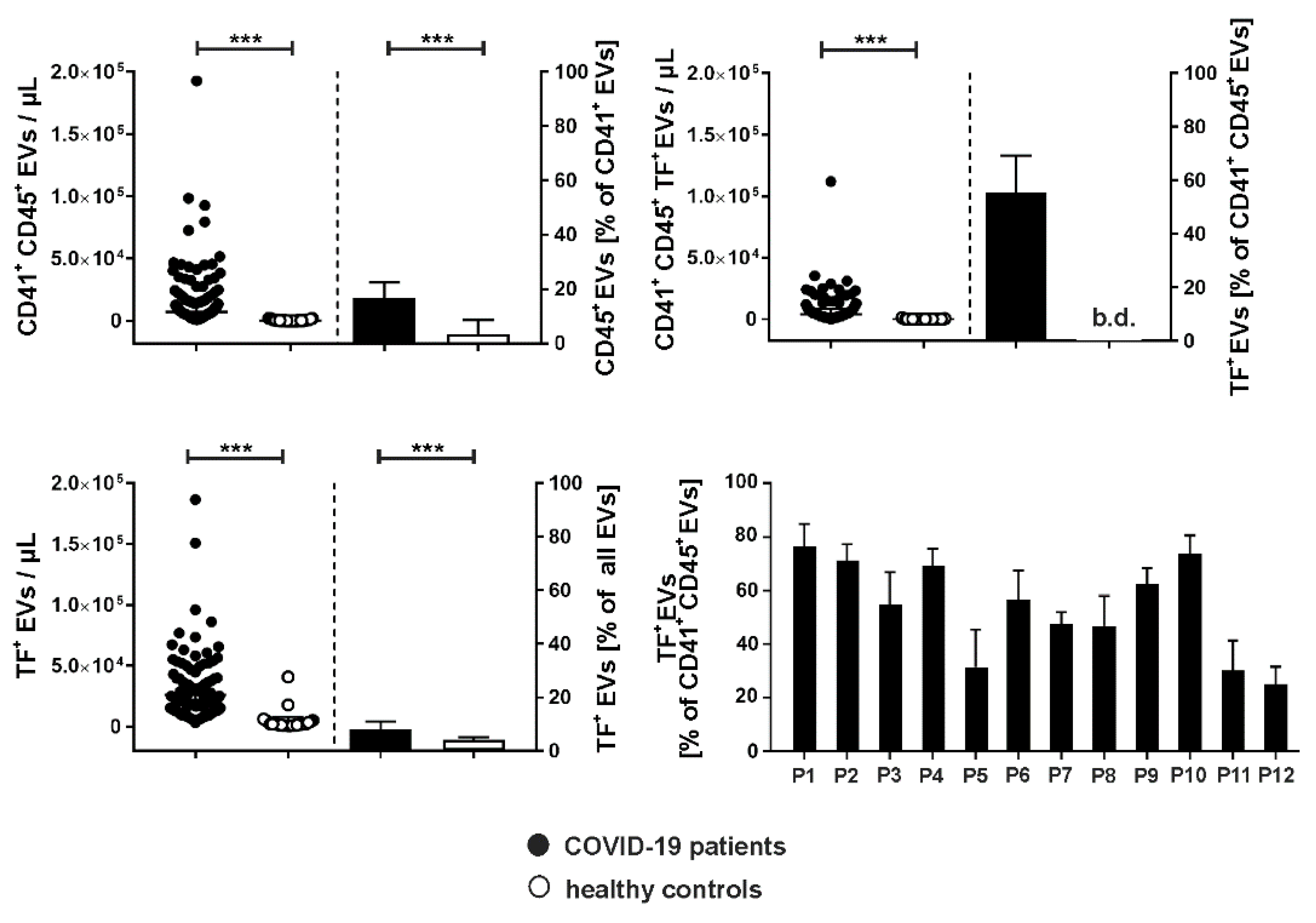

2.4. Tissue Factor Expression on Platelet- and Leukocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

2.5. Time Course of Coagulation- and Inflammation-Related Mediators

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Sample Collection

4.2. Flow Cytometric Characterization of Phosphatidylserine-Exposing Extracellular Vesicles

4.3. Quantification of Cytokines, Chemokines, and Growth Factors

4.4. Quantification of PF4, HMGB-1, and Nucleosomes

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonaventura, A.; Vecchie, A.; Dagna, L.; Martinod, K.; Dixon, D.L.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Dentali, F.; Montecucco, F.; Massberg, S.; Levi, M.; Abbate, A. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; Endeman, H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portier, I.; Campbell, R.A.; Denorme, F. Mechanisms of immunothrombosis in COVID-19. Curr Opin Hematol 2021, 28, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrottmaier, W.C.; Mussbacher, M.; Salzmann, M.; Assinger, A. Platelet-leukocyte interplay during vascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2020, 307, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, B.; Massberg, S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzano, P.; Brambilla, M.; Porro, B.; Cosentino, N.; Tortorici, E.; Vicini, S.; Poggio, P.; Cascella, A.; Pengo, M.F.; Veglia, F.; Fiorelli, S.; Bonomi, A.; Cavalca, V.; Trabattoni, D.; Andreini, D.; Omodeo Sale, E.; Parati, G.; Tremoli, E.; Camera, M. Platelet and Endothelial Activation as Potential Mechanisms Behind the Thrombotic Complications of COVID-19 Patients. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2021, 6, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.D.; Quirino-Teixeira, A.C.; Merij, L.B.; Pinheiro, M.B.M.; Rozini, S.V.; Bozza, F.A.; Bozza, P.T. Platelet-leukocyte interactions in the pathogenesis of viral infections. Platelets 2022, 33, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manne, B.K.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.A.; Portier, I.; Rowley, J.W.; Stubben, C.; Petrey, A.C.; Tolley, N.D.; Guo, L.; Cody, M.; Weyrich, A.S.; Yost, C.C.; Rondina, M.T.; Campbell, R.A. Platelet gene expression and function in patients with COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hottz, E.D.; Bozza, P.T. Platelet-leukocyte interactions in COVID-19: Contributions to hypercoagulability, inflammation, and disease severity. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2022, 6, e12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Puhm, F.; Allaeys, I.; Naya, A.; Oudghiri, M.; Khalki, L.; Limami, Y.; Zaid, N.; Sadki, K.; Ben El Haj, R.; Mahir, W.; Belayachi, L.; Belefquih, B.; Benouda, A.; Cheikh, A.; Langlois, M.A.; Cherrah, Y.; Flamand, L.; Guessous, F.; Boilard, E. Platelets Can Associate with SARS-Cov-2 RNA and Are Hyperactivated in COVID-19. Circ Res 2020, 127, 1404–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Joncour, A.; Biard, L.; Vautier, M.; Bugaut, H.; Mekinian, A.; Maalouf, G.; Vieira, M.; Marcelin, A.G.; Rosenzwajg, M.; Klatzmann, D.; Corvol, J.C.; Paccoud, O.; Carillion, A.; Salem, J.E.; Cacoub, P.; Boulaftali, Y.; Saadoun, D. Neutrophil-Platelet and Monocyte-Platelet Aggregates in COVID-19 Patients. Thromb Haemost 2020, 120, 1733–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.D.; Martins-Goncalves, R.; Palhinha, L.; Azevedo-Quintanilha, I.G.; de Campos, M.M.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Temerozo, J.R.; Soares, V.C.; Dias, S.S.G.; Teixeira, L.; Castro, I.; Righy, C.; Souza, T.M.L.; Kurtz, P.; Andrade, B.B.; Nakaya, H.I.; Monteiro, R.Q.; Bozza, F.A.; Bozza, P.T. Platelet-monocyte interaction amplifies thromboinflammation through tissue factor signaling in COVID-19. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 5085–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendros, P.; Mitsios, A.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; Mastellos, D.C.; Metallidis, S.; Rafailidis, P.; Ntinopoulou, M.; Sertaridou, E.; Tsironidou, V.; Tsigalou, C.; Tektonidou, M.; Konstantinidis, T.; Papagoras, C.; Mitroulis, I.; Germanidis, G.; Lambris, J.D.; Ritis, K. Complement and tissue factor-enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID-19 immunothrombosis. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 6151–6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambas, K.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; Vassilopoulos, D.; Apostolidou, E.; Skendros, P.; Girod, A.; Arelaki, S.; Froudarakis, M.; Nakopoulou, L.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Koffa, M.; Boumpas, D.T.; Ritis, K.; Mitroulis, I. Tissue factor expression in neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophil derived microparticles in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis may promote thromboinflammation and the thrombophilic state associated with the disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2014, 73, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, T.J.; Vu, T.T.; Swystun, L.L.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Mai, S.H.; Weitz, J.I.; Liaw, P.C. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. NETosis and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in COVID-19: Immunothrombosis and Beyond. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 838011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.A.; He, X.Y.; Denorme, F.; Campbell, R.A.; Ng, D.; Salvatore, S.P.; Mostyka, M.; Baxter-Stoltzfus, A.; Borczuk, A.C.; Loda, M.; Cody, M.J.; Manne, B.K.; Portier, I.; Harris, E.S.; Petrey, A.C.; Beswick, E.J.; Caulin, A.F.; Iovino, A.; Abegglen, L.M.; Weyrich, A.S.; Rondina, M.T.; Egeblad, M.; Schiffman, J.D.; Yost, C.C. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood 2020, 136, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripisciano, C.; Weiss, R.; Eichhorn, T.; Spittler, A.; Heuser, T.; Fischer, M.B.; Weber, V. Different Potential of Extracellular Vesicles to Support Thrombin Generation: Contributions of Phosphatidylserine, Tissue Factor, and Cellular Origin. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, A.P., 3rd; Mackman, N. Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res 2011, 108, 1284–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, V.; Lambour, A.; Swinyard, B.; Zerbib, Y.; Diouf, M.; Soudet, S.; Brochot, E.; Six, I.; Maizel, J.; Slama, M.; Guillaume, N. Annexin-V positive extracellular vesicles level is increased in severe COVID-19 disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1186122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, A.; Havervall, S.; von Meijenfeldt, F.; Hisada, Y.; Aguilera, K.; Grover, S.P.; Lisman, T.; Mackman, N.; Thalin, C. Patients With COVID-19 Have Elevated Levels of Circulating Extracellular Vesicle Tissue Factor Activity That Is Associated With Severity and Mortality-Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021, 41, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrello, J.; Caporali, E.; Gauthier, L.G.; Pianezzi, E.; Balbi, C.; Rigamonti, E.; Bolis, S.; Lazzarini, E.; Biemmi, V.; Burrello, A.; Frigerio, R.; Martinetti, G.; Fusi-Schmidhauser, T.; Vassalli, G.; Ferrari, E.; Moccetti, T.; Gori, A.; Cretich, M.; Melli, G.; Monticone, S.; Barile, L. Risk stratification of patients with SARS-CoV-2 by tissue factor expression in circulating extracellular vesicles. Vascul Pharmacol 2022, 145, 106999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, C.; Burrello, J.; Bolis, S.; Lazzarini, E.; Biemmi, V.; Pianezzi, E.; Burrello, A.; Caporali, E.; Grazioli, L.G.; Martinetti, G.; Fusi-Schmidhauser, T.; Vassalli, G.; Melli, G.; Barile, L. Circulating extracellular vesicles are endowed with enhanced procoagulant activity in SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 2021, 67, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guervilly, C.; Bonifay, A.; Burtey, S.; Sabatier, F.; Cauchois, R.; Abdili, E.; Arnaud, L.; Lano, G.; Pietri, L.; Robert, T.; Velier, M.; Papazian, L.; Albanese, J.; Kaplanski, G.; Dignat-George, F.; Lacroix, R. Dissemination of extreme levels of extracellular vesicles: tissue factor activity in patients with severe COVID-19. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, S.J.; Hisada, Y.; Bae-Jump, V.L.; Mackman, N. Evaluation of a new bead-based assay to measure levels of human tissue factor antigen in extracellular vesicles in plasma. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2022, 6, e12677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braig, D.; Nero, T.L.; Koch, H.G.; Kaiser, B.; Wang, X.; Thiele, J.R.; Morton, C.J.; Zeller, J.; Kiefer, J.; Potempa, L.A.; Mellett, N.A.; Miles, L.A.; Du, X.J.; Meikle, P.J.; Huber-Lang, M.; Stark, G.B.; Parker, M.W.; Peter, K.; Eisenhardt, S.U. Transitional changes in the CRP structure lead to the exposure of proinflammatory binding sites. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, N.; De Lorenzo, R.; Clementi, N.; Antonia Diotti, R.; Criscuolo, E.; Godino, C.; Tresoldi, C.; Angels For Covid-Bio, B.S.G.B.; Bonini, C.; Clementi, M.; Mancini, N.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Manfredi, A.A. Unconventional CD147-dependent platelet activation elicited by SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2022, 20, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahyra, A.S.C.; Calado, R.T.; Almeida, F. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in COVID-19 Pathology. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.Y.; Chee, K.; Wong, S.W.; Tan, G.B.; Ang, H.; Leung, B.P.; Tan, C.W.; Ramanathan, K.; Dalan, R.; Cheung, C.; Lye, D.C.; Young, B.E.; Yap, E.S.; Chia, Y.W.; Fan, B.E.; Clotting, C.-. .; Bleeding, I. Increased Platelet Activation demonstrated by Elevated CD36 and P-Selectin Expression in 1-Year Post-Recovered COVID-19 Patients. Semin Thromb Hemost 2023, 49, 561–564. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, R.L. Type 2 scavenger receptor CD36 in platelet activation: the role of hyperlipemia and oxidative stress. Clin Lipidol 2009, 4, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavello, M.; Vizio, B.; Bosco, O.; Pivetta, E.; Mariano, F.; Montrucchio, G.; Lupia, E. Extracellular Vesicles: New Players in the Mechanisms of Sepsis- and COVID-19-Related Thromboinflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Massri, M.; Grasse, M.; Fleischer, V.; Kellnerova, S.; Harpf, V.; Knabl, L.; Knabl, L., Sr.; Heiner, T.; Kummann, M.; Neurauter, M.; Rambach, G.; Speth, C.; Wurzner, R. Systemic Inflammation and Complement Activation Parameters Predict Clinical Outcome of Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhm, F.; Flamand, L.; Boilard, E. Platelet extracellular vesicles in COVID-19: Potential markers and makers. J Leukoc Biol 2022, 111, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellano, G.; Raineri, D.; Rolla, R.; Giordano, M.; Puricelli, C.; Vilardo, B.; Manfredi, M.; Cantaluppi, V.; Sainaghi, P.P.; Castello, L.; De Vita, N.; Scotti, L.; Vaschetto, R.; Dianzani, U.; Chiocchetti, A. Circulating Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are a Hallmark of Sars-Cov-2 Infection. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traby, L.; Kollars, M.; Kussmann, M.; Karer, M.; Sinkovec, H.; Lobmeyr, E.; Hermann, A.; Staudinger, T.; Schellongowski, P.; Rossler, B.; Burgmann, H.; Kyrle, P.A.; Eichinger, S. Extracellular Vesicles and Citrullinated Histone H3 in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients. Thromb Haemost 2022, 122, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, J.; Handberg, A.; Simonsen, J.B. Lipid-based strategies used to identify extracellular vesicles in flow cytometry can be confounded by lipoproteins: Evaluations of annexin V, lactadherin, and detergent lysis. J Extracell Vesicles 2022, 11, e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendl, B.; Weiss, R.; Eichhorn, T.; Linsberger, I.; Afonyushkin, T.; Puhm, F.; Binder, C.J.; Fischer, M.B.; Weber, V. Extracellular vesicles are associated with C-reactive protein in sepsis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habersberger, J.; Strang, F.; Scheichl, A.; Htun, N.; Bassler, N.; Merivirta, R.M.; Diehl, P.; Krippner, G.; Meikle, P.; Eisenhardt, S.U.; Meredith, I.; Peter, K. Circulating microparticles generate and transport monomeric C-reactive protein in patients with myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2012, 96, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottz, E.D.; Azevedo-Quintanilha, I.G.; Palhinha, L.; Teixeira, L.; Barreto, E.A.; Pao, C.R.R.; Righy, C.; Franco, S.; Souza, T.M.L.; Kurtz, P.; Bozza, F.A.; Bozza, P.T. Platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation trigger tissue factor expression in patients with severe COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, N.; Campana, L.; Gavina, M.; Covino, C.; De Metrio, M.; Panciroli, C.; Maiuri, L.; Maseri, A.; D'Angelo, A.; Bianchi, M.E.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Manfredi, A.A. Activated platelets present high mobility group box 1 to neutrophils, inducing autophagy and promoting the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Thromb Haemost 2014, 12, 2074–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, C.; Van Den Helm, S.; Letunica, N.; Attard, C.; Karlaftis, V.; Cai, T.; Praporski, S.; Swaney, E.; Burgner, D.; Neeland, M.; Dohle, K.; Crawford, N.W.; Clucas, L.; Tosif, S.; Ignjatovic, V.; Monagle, P. Increased platelet activation in SARS-CoV-2 infected non-hospitalised children and adults, and their household contacts. Br J Haematol 2021, 195, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterud, B. Tissue factor expression by monocytes: regulation and pathophysiological roles. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1998, 9 (Suppl 1), S9–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Hisada, Y.; Sachetto, A.T.A.; Mackman, N. Circulating tissue factor-positive extracellular vesicles and their association with thrombosis in different diseases. Immunol Rev 2022, 312, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournazos, S.; Rennie, J.; Hart, S.P.; Fox, K.A.; Dransfield, I. Monocyte functional responsiveness after PSGL-1-mediated platelet adhesion is dependent on platelet activation status. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008, 28, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakos, D.A.; Kambas, K.; Konstantinidis, T.; Mitroulis, I.; Apostolidou, E.; Arelaki, S.; Tsironidou, V.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Skendros, P.; Konstantinides, S.; Ritis, K. Expression of functional tissue factor by neutrophil extracellular traps in culprit artery of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, T.; Huber, S.; Weiss, R.; Ebeyer-Masotta, M.; Laukova, L.; Emprechtinger, R.; Bellmann-Weiler, R.; Lorenz, I.; Martini, J.; Pirklbauer, M.; Orth-Holler, D.; Wurzner, R.; Weber, V. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Is Associated with Elevated Levels of IP-10, MCP-1, and IL-13 in Sepsis Patients. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, T.J.; Ungaro, R.; Dirain, M.; Efron, P.A.; Mazer, M.B.; Remy, K.E.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Zhong, L.; Bacher, R.; Starostik, P.; Moldawer, L.L.; Brakenridge, S.C. Overlapping but Disparate Inflammatory and Immunosuppressive Responses to SARS-CoV-2 and Bacterial Sepsis: An Immunological Time Course Analysis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 792448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.K.; Laukova, L.; Weiss, R.; Semak, V.; Fendl, B.; Weiss, V.U.; Steinberger, S.; Allmaier, G.; Tripisciano, C.; Weber, V. Comparative Analysis of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Using Flow Cytometry and Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeyer-Masotta, M.; Eichhorn, T.; Weiss, R.; Semak, V.; Laukova, L.; Fischer, M.B.; Weber, V. Heparin-Functionalized Adsorbents Eliminate Central Effectors of Immunothrombosis, including Platelet Factor 4, High-Mobility Group Box 1 Protein and Histones. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruschke, J.K.; Liddell, T.M. The Bayesian New Statistics: Hypothesis testing, estimation, meta-analysis, and power analysis from a Bayesian perspective. Psychon Bull Rev 2018, 25, 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szucs, D.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. When Null Hypothesis Significance Testing Is Unsuitable for Research: A Reassessment. Front Hum Neurosci 2017, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; D'Agostino McGowan, L.; Francois, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; Kuhn, M.; Lin Pedersen, T.; Miller, E.; Milton Bache, S.; Müller, K.; Ooms, J.; Robinson, D.; Seidel, D.P.; Spinu, V.; Takahashi, K.; Vaughan, D.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Soure Softw 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P.C. brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. J Stat Soft 2017, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| COVID-19 (n=12) |

Survivors (n=5) |

Non-survivors(n=7) | Controls (n=25) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 79.5 [77.0–82.9] | 78.1 [70.6–83.9] | 80.6 [77.8–81.5] | 29.1 [27.4–42.9] |

| Female | 2 (17 %) | 1 (20 %) | 1 (14 %) | 15 (60 %) |

| Male | 10 (83 %) | 4 (80 %) | 6 (86 %) | 10 (40 %) |

| Mortality | 7 (58 %) | |||

| Secondary infections | 7 (58 %) | |||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 10 (83) | 4 (80) | 6 (86) | n.a. |

| Renal/genitourinary | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | n.a. |

| Endocrine | 2 (17) | 1 (20) | 1 (14) | n.a. |

| Metabolic | 6 (50) | 2 (40) | 4 (57) | n.a. |

| Musculoskeletal | 1 (8) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | n.a. |

| Psychiatric/mental | 2 (17) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | n.a. |

| Autoimmune/immunological | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | n.a. |

| Cancer | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | n.a. |

| Parameter | Pincrease | Pdecrease | Estimate | Estimate Error | CIlower | CIupper | Rhat | Bulk ESS | Tail ESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes [cells/µL] | 0.07 | 99.92 | -153.67 | 48.1 | -246.91 | -58.22 | 1 | 2344.63 | 2722.01 |

| Neutrophils [cells/µL] | 0 | 100 | -213.65 | 47.33 | -308.98 | -118.91 | 1.01 | 3150.99 | 2606.26 |

| Platelets [cells/µL] | 0.9 | 99.1 | -7024.9 | 2941.64 | -12,645.01 | -1393.28 | 1 | 6704.61 | 2862.77 |

| PF4 [ng/mL] | 0 | 100 | -53.12 | 9.13 | -70.53 | -35.17 | 1 | 3299.33 | 3140.46 |

| D-dimer [ng/L] | 95.97 | 4.03 | 0.1 | 0.06 | -0.02 | 0.2 | 1 | 2889.52 | 2843.01 |

| Nucleosomes [AU] | 99.22 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 1 | 3642.96 | 2814.7 |

| HMGB-1 [ng/mL] | 92.67 | 7.33 | 0.42 | 0.28 | -0.15 | 0.96 | 1 | 3536.52 | 2048.85 |

| EVs [events/µL] | 4.65 | 95.35 | -10,038.83 | 5802.75 | -21,576.23 | 1638.06 | 1 | 6796.11 | 3067.23 |

| TF+ EVs [events/µL] | 0 | 100 | -1543.5 | 479.62 | -2716.92 | -813.98 | 1.38 | 8.97 | 13.71 |

| CRP+ EVs [events/µL] | 0.07 | 99.92 | -6998.63 | 2129.1 | -11,234.85 | -2893.5 | 1 | 6375.93 | 3141 |

| CRP [mg/L] | 75.8 | 24.2 | 0.65 | 0.93 | -1.14 | 2.52 | 1 | 3608.36 | 2938.3 |

| PCT [ng/mL] | 53.42 | 46.58 | 0 | 0.03 | -0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 2454.24 | 2441.22 |

| IL-1β [pg/mL] | 99.98 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 1 | 2596.99 | 2760.37 |

| IL-6 [pg/mL] | 40.95 | 59.05 | -1.7 | 7.5 | -16.63 | 13.11 | 1 | 4165.65 | 3158.01 |

| IL-8 [pg/mL] | 100 | 0 | 2.84 | 0.51 | 1.85 | 3.83 | 1 | 3460.46 | 2930.64 |

| IL-10 [pg/mL] | 95.95 | 4.05 | 0.15 | 0.09 | -0.02 | 0.33 | 1 | 3720.19 | 3263.86 |

| IFN-γ [pg/mL] | 71.25 | 28.75 | 0.13 | 0.22 | -0.31 | 0.56 | 1 | 2979.59 | 2620.35 |

| TNF-α [pg/mL] | 97.97 | 2.03 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 1.39 | 1 | 3549.91 | 2730.32 |

| IP-10 [pg/mL] | 0 | 100 | -171.03 | 29.29 | -228.73 | -112.8 | 1 | 1797.06 | 2200.2 |

| MCP-1 [pg/mL] | 69.5 | 30.5 | 2.08 | 4.1 | -6.18 | 10 | 1 | 2603.32 | 2691.08 |

| G-CSF [pg/mL] | 99.72 | 0.28 | 6.87 | 2.6 | 1.69 | 11.77 | 1 | 3776.26 | 3357.83 |

| Flow cytometry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Origin | Clone | Marker for | Fluorochrome | Abbreviation | Supplier |

| CD41 | mouse | P2 | platelets | PhycoerythrinCyanin 7 | PC7 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD235a | mouse | HIR2 (GA-R2) | red blood cells | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

FITC | eBioscience |

| CD105 | mouse | 266 | endothelial cells | Phycoerythrin | PE | Becton Dickinson |

| CD45 | mouse | J33 | leukocytes | Pacific Blue | PB | Beckman Coulter |

| CD36 | mouse | 5-271 | platelet glycoprotein IV | Alexa Fluor 700 | AF700 | BioLegend |

| PF4 | mouse | # 170138 | platelet factor 4 | Phycoerythrin | PE | R&D Systems |

| CRP | goat | - | C-reactive protein | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

FITC | Abcam |

| TF | mouse | VD8 | tissue factor | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

FITC | BioMedica Diagnostics |

| HMGB-1 | mouse | 115603 | high mobility group box-1 protein | Alexa Fluor 700 | AF700 | R&D Systems |

| Anx5 | - | - | phosphatidylserine | Allophyco-cyanin | APC | BD Biosciences |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).