Submitted:

16 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

2.4. Culture of human bronchial epithelial cells

2.5. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background and characteristics of the ECRS and non-ECRS subjects

3.2. Target gene expressions in sinonasal mucosa

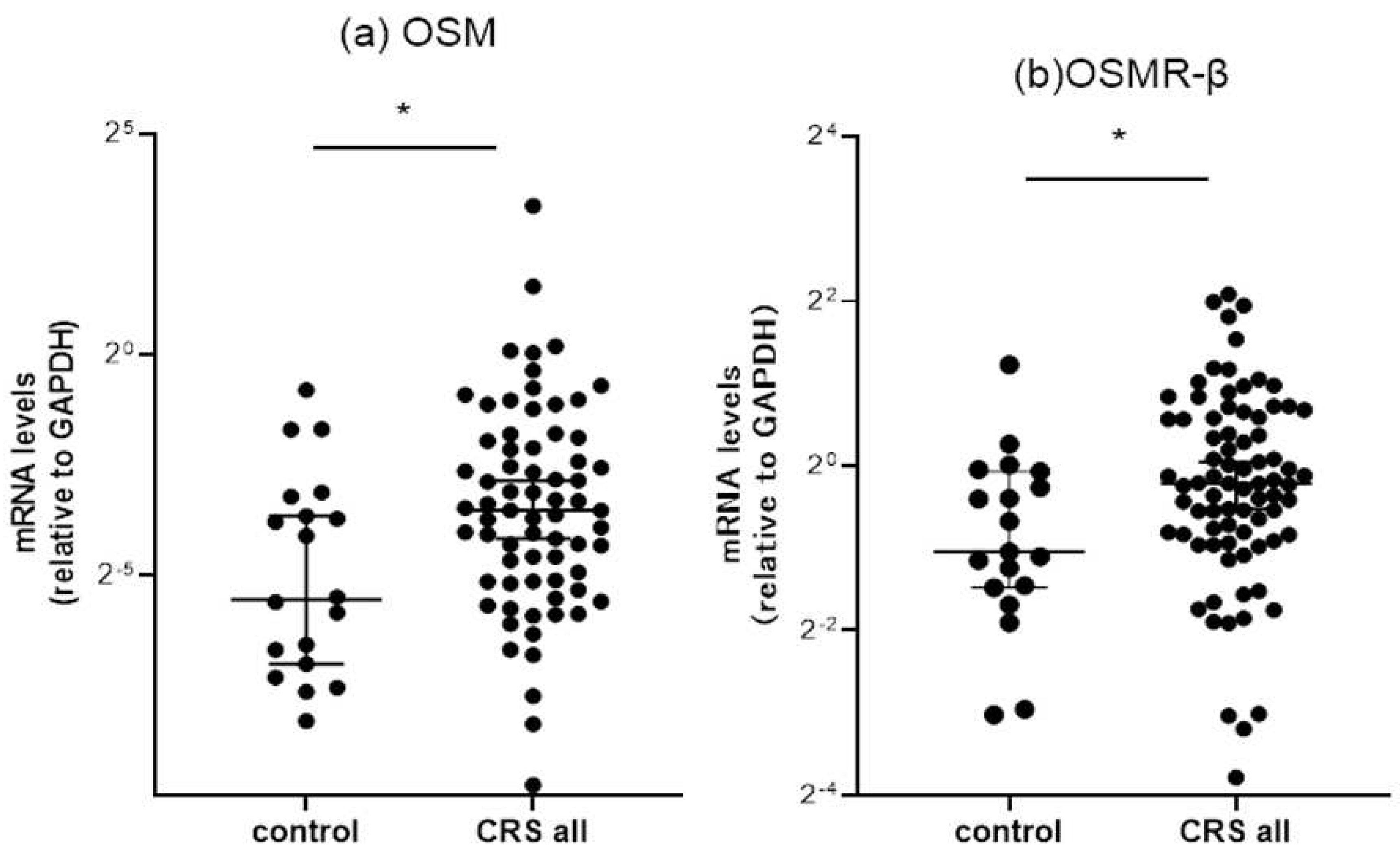

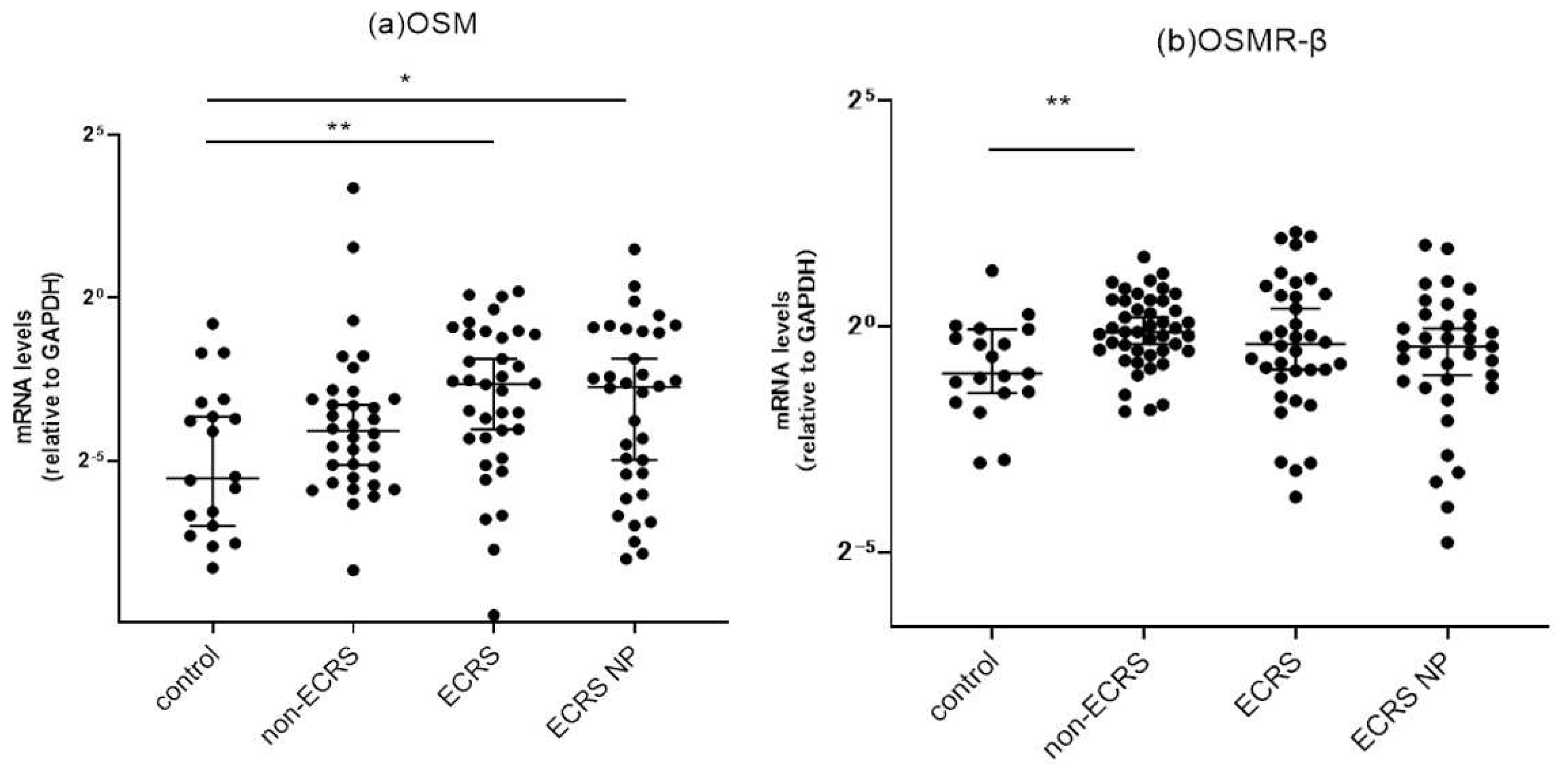

3.2.1. Comparison of OSM and OSMR mRNA expressions between the controls and CRS patients

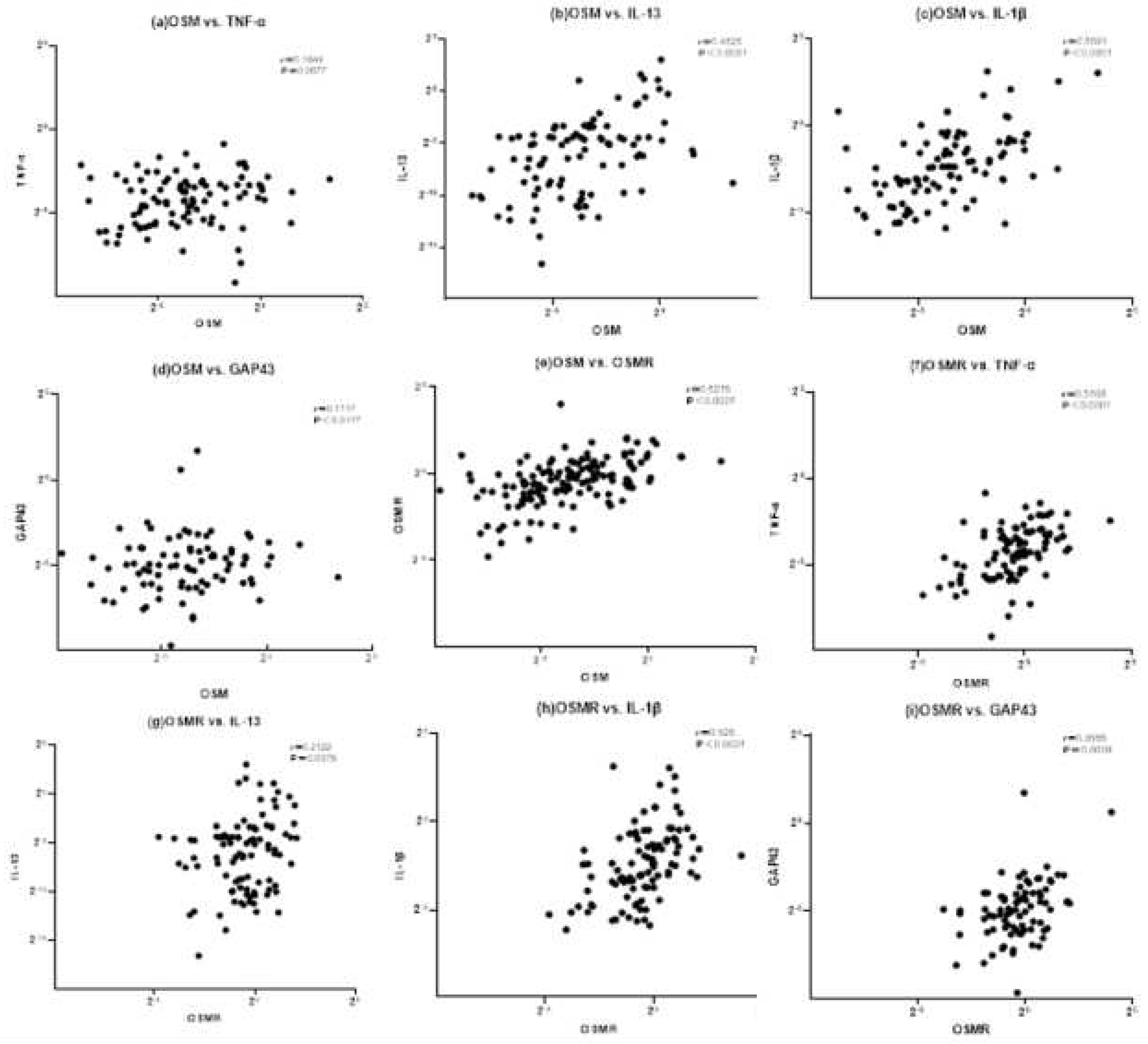

3.1.2. Correlation with inflammatory cytokines

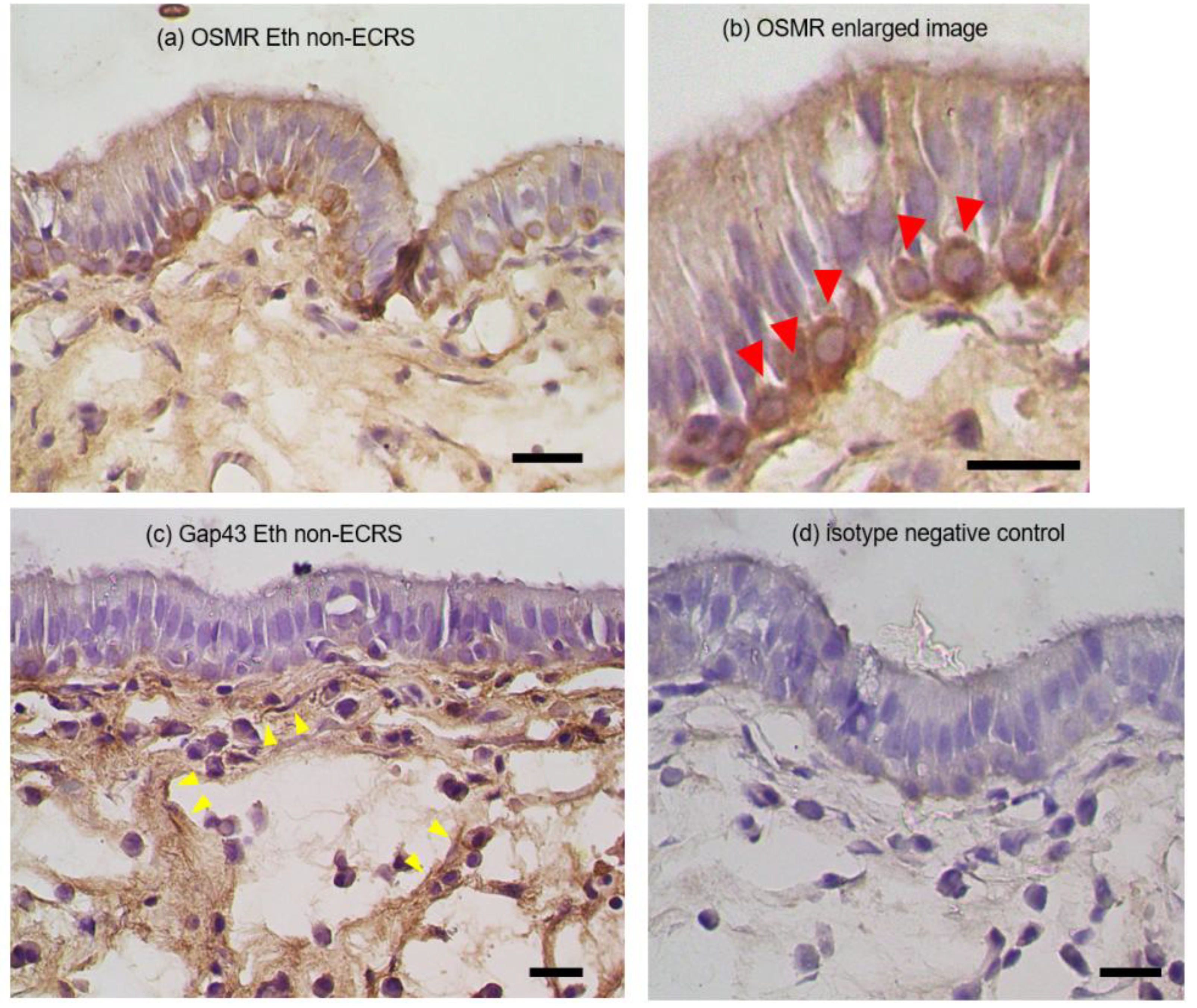

3.3. Immunohistochemical observation

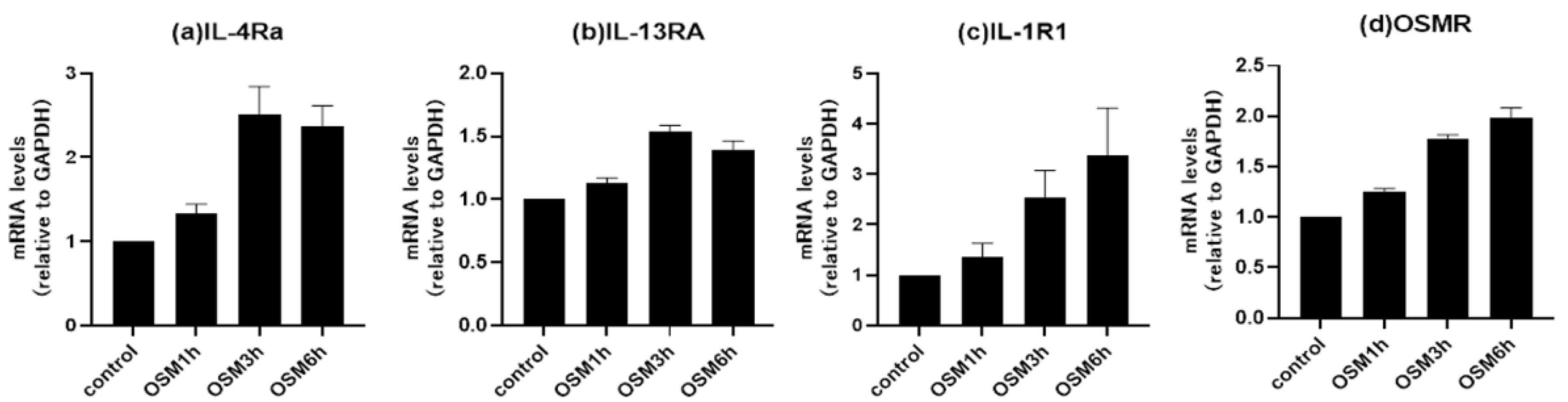

3.4. Changes in receptor expression upon OSM stimulation in human airway epithelial cells

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kato, A.; Peters, A.T.; Stevens, W.W.; Schleimer, R.P.; Tan, B.K.; Kern, R.C.; Endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: Relationships to disease phenotypes, pathogenesis, clinical findings, and treatment approaches. Allergy 2022, 77, 812-826. [CrossRef]

- Tomassen, P.; Vandeplas, G.; Van, Z.T.; Cardell, L.O.; Arebro, J.; Olze, H.; Förster, R.U.; Kowalski, M.L.; Olszewska, Z.A.; Holtappels, G.; et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1449-1456. PMID: 26949058 . [CrossRef]

- Ishino, T.; Takeno, S.; Takemoto, K.; Yamato, K.; Oda, T.; Nishida, M.; Horibe, Y.; Chikuie, N.; Kono, T.; Taruya, T.; et al. Distinct Gene Set Enrichment Profiles in Eosinophilic and Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps by Bulk RNA Barcoding and Sequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10 5653. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Delemarre, T.; Cavaliere, C.; Zhang, N.; Bachert, C. Advances in chronic rhinosinusitis in 2020 and 2021. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 854-866. [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Schleimer, R.P.; Bleier, B.S. Mechanisms and pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1491-1503. [CrossRef]

- Fujieda, S.; Imoto, Y.; Kato, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Tsutsumiuchi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kidoguchi, M.; Takabayashi, T.; Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol. Int. 2019, 68, 403-412. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, T.; Sakashita, M.; Haruna, T.; Asaka, D.; Takeno, S.; Ikeda, H.; Nakayama, T.; Seki, N.; Ito, S.; Murata, J.; et al. Novel scoring system and algorithm for classifying chronic rhinosinusitis: the JESREC Study. Allergy 2015, 70, 995-1003. doi: 10.1111/all.12644. PMID: 25945591.

- Rose, T.M.; Bruce, A.G. Oncostatin M is a member of a cytokine family that includes leukemia-inhibitory factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and interleukin 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991, 88(19), 8641-5. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Morikawa, Y.; Miyajima, A.; Senba, E. Expression of oncostatin M in hematopoietic organs. Dev. Dyn. 2002, 225, 327-31. [CrossRef]

- Gearing, D.P.; Comeau, M.R.; Friend, D.J.; Gimpel, S.D.; Thut, C.J.; McGourty, J.; Brasher, K.K.; King, J.A.; Gillis, S.; Mosley, B.; et al. The IL-6 signal transducer, gp130: an oncostatin M receptor and affinity converter for the LIF receptor. Science 1992, 255, 1434-1437. [CrossRef]

- Pothoven, K.L.; Norton, J.E.; Hulse, K.E.; Suh, L.A.; Carter, R.G.; Rocci, E.; Harris, K.E.; Shintani-Smith, S.; Conley, D.B.; Chandra, R.K. Oncostatin M promotes mucosal epithelial barrier dysfunction, and its expression is increased in patients with eosinophilic mucosal disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 737-746.e4. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.L.; Baines, K.J.; Boyle, M.J.; Scott, R.J.; Gibson, P.G. Oncostatin M (OSM) is increased in asthma with incompletely reversible airflow obstruction. Exp. Lung Res. 2009, 35, 781-94. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Hwang, S.J.; Chae, S.W.; Woo, J.S.; Lee, H.M. Upregulation of oncostatin m in allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 2213-6. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.K.; Kerr, C.; Fattouh, R.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Khan, W.I.; Jordana, M.; Richards, C.D. A mouse model of airway disease: oncostatin M-induced pulmonary eosinophilia, goblet cell hyperplasia, and airway hyperresponsiveness are STAT6 dependent, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis is STAT6 independent. J. Immunol. 2011, 186(2), 1107-18. [CrossRef]

- Lund, V.J.; Kennedy, D.W. Quantification for staging sinusitis. The Staging and Therapy Group. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 1995, 167, 17‒21. [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, K.; Lomude, L.S.; Takeno, S.; Kawasumi, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Hamamoto, T.; Ishino, T.; Ando, Y.; Ishikawa, C.; Ueda, T. Functional Alteration and Differential Expression of the Bitter Taste Receptor T2R38 in Human Paranasal Sinus in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(5), 4499. [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Ueki, S.; Tamari, M.; Imoto, Y.; Fujieda, S.; Taniguchi, M. Adult-onset eosinophilic airway diseases. Allergy 2020, 75, 3087-3099. [CrossRef]

- Pothoven, K.L.; Schleimer, R.P. The barrier hypothesis and Oncostatin M: Restoration of epithelial barrier function as a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of type 2 inflammatory disease. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1341367. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Jenkins, B.J. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 773-789. [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.D. The enigmatic cytokine oncostatin m and roles in disease. ISRN Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 512103. [CrossRef]

- West, N.R.; Owens, B.M.J.; Hegazy, A.N. The oncostatin M-stromal cell axis in health and disease. Scand. J. Immunol. 2018, 88, e12694. [CrossRef]

- Le Goff, B.; Singbrant, S.; Tonkin, B.A.; Martin, T.J.; Romas, E.; Sims, N.A.; Walsh, N.C. Oncostatin M acting via OSMR, augments the actions of IL-1 and TNF in synovial fibroblasts. Cytokine 2014, 68, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Hui, W.; Rowan, A.D.; Richards, C.D.; Cawston, T.E. Oncostatin M in combination with tumor necrosis factor alpha induces cartilage damage and matrix metalloproteinase expression in vitro and in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 3404-18. [CrossRef]

- Pothoven, K.L.; Norton, J.E.; Suh, L.A.; Carter, R.G.; Harris, K.E.; Biyasheva, A.; Welch, K.; Shintani-Smith, S.; Conley, D.B.; Liu, M.C.; et al. Neutrophils are a major source of the epithelial barrier disrupting cytokine oncostatin M in patients with mucosal airways disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1966-1978.e9. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.K.; Kerr, C.; Fattouh, R.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Khan, W.I.; Jordana, M.; Richards, C.D. A mouse model of airway disease: oncostatin M-induced pulmonary eosinophilia, goblet cell hyperplasia, and airway hyperresponsiveness are STAT6 dependent, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis is STAT6 independent. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1107-18. [CrossRef]

- Sofen, H.; Bissonnette, R.; Yosipovitch, G.; Silverberg, J.I.; Tyring, S.; Loo, W.J.; Zook, M.; Lee, M.; Zou, L.; Jiang, G.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of vixarelimab, a human monoclonal oncostatin M receptor β antibody, in moderate-to-severe prurigo nodularis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101826. [CrossRef]

| controls | non-ECRS | ECRS | |

| Number (male/female) | 20 (6/14) | 35 (21/14) | 36 (18/18) |

| Age (mean±SD) | 49.6±15.6 | 51.5±15.4 | 54.5±10.2 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 8 (53.3%) | 25 (71.4%) | 27 (75%) |

| BMI (kg/mm2) (mean±SD) | 22.4±4.2 | 23.3±3.8 | 22.6±3.6 |

| Bronchial asthma (%) | 1 (5%) | 5 (14.3%) | 17 (47.2%)**††† |

| Blood eosinophils (%) (median, range) | 2.5 (0.0-6.6) | 1.6 (0.0-20.0) | 6.8 (1.1-13.9)****††† |

| Tissue eosinophils (cells/HPF) (median, range) | 4.97 (0.0-23.0) | 7.3 (0.0-70.3) †† | 117.0 (4.0-383.3)****††† |

| CT score (mean±SD) | 2.45±4.24 | 7.7±5.2††† | 14.8±5.0****††† |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).