Submitted:

12 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. METHODS

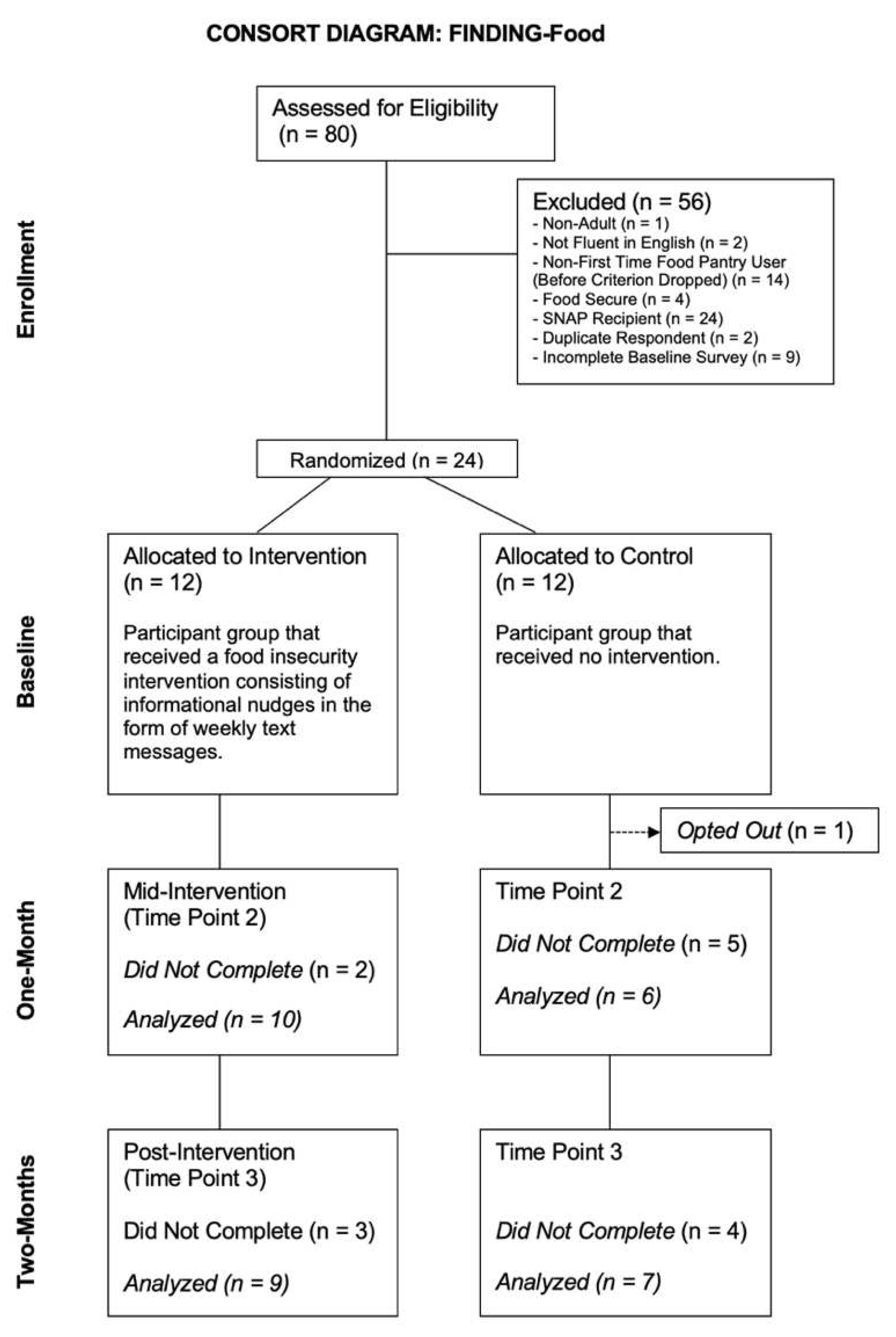

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Theoretical Model

2.3. Setting

2.4. Participant Sampling

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Study Measures

2.6.1. Participant Characteristics

2.6.2. Food Security

2.6.3. Food Pantry Utilization and SNAP Enrollment

2.6.4. Intervention Acceptability

2.7. Data Collection

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. RESULTS

3.1. Limited Efficacy Testing

3.2. Intervention Acceptability

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Food Security in the U.S. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/#:~:text=Food%20security%20means%20access%20by,in%20U.S.%20households%20and%20communities.

- 2. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Hashad RM, Hales L, Gregory CA. Definitions of Food Security: Ranges of Food Security and Food Insecurity. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2022. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Coleman-Jensen A, Hales L. Food Security in the United States: Trends in U.S. food security. Economic Research Report - United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2022;https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/interactive-charts-and-highlights/#trends.

- Sharareh, N.; Adesoba, T.P.; Wallace, A.S.; Bybee, S.; Potter, L.N.; Seligman, H.; Wilson, F.A. Associations between food insecurity and other social risk factors among U.S. adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 39, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations - Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development: The 17 Goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Bhattacharya, J.; Currie, J.; Haider, S. Poverty, food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. J. Heal. Econ. 2004, 23, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel MM, Armijos RX. Food insecurity, Cardiometabolic health, and health care in US-Mexico border immigrant adults: An exploratory study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2019;21(5):1085-1094.

- Gowda, C.; Hadley, C.; Aiello, A.E. The Association Between Food Insecurity and Inflammation in the US Adult Population. Am. J. Public Heal. 2012, 102, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Sherry, B.; Njai, R.; Blanck, H.M. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Obesity among US Adults in 12 States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strings, S.; Ranchod, Y.K.; Laraia, B.; Nuru-Jeter, A. Race and Sex Differences in the Association between Food Insecurity and Type 2 Diabetes. Ethn. Dis. 2016, 26, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Rong, S.; Du, Y.; Xu, G.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Wallace, R.B.; Bao, W. Food Insecurity Is Associated With Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality Among Adults in the United States. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e014629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gany, F.; Lee, T.; Ramirez, J.; Massie, D.; Moran, A.; Crist, M.; McNish, T.; Winkel, G.; Leng, J.C. Do Our Patients Have Enough to Eat?: Food Insecurity among Urban Low-income Cancer Patients. J. Heal. Care Poor Underserved 2014, 25, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.; Maddocks, E.; Chen, Y.; Gilman, S.; Colman, I. Food insecurity and mental illness: disproportionate impacts in the context of perceived stress and social isolation. Public Heal. 2016, 132, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Garcia, T.; Leung, C.W. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Depression, Anxiety, and Stress: Evidence from the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Heal. Equity 2021, 5, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Laraia, B.A. Household Food Insecurity Is Positively Associated with Depression among Low-Income Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participants and Income-Eligible Nonparticipants. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.M.; A Frongillo, E.; Leung, C.; Ritchie, L. No food for thought: Food insecurity is related to poor mental health and lower academic performance among students in California’s public university system. J. Heal. Psychol. 2020, 25, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, L.; Lioret, S.; van der Waerden, J.; Fombonne. ; Falissard, B.; Melchior, M. Food insecurity and mental health problems among a community sample of young adults. Chest 2016, 51, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, M.F.; Ojinnaka, C.O.; Bruening, M. Food Insecurity is Related to Disordered Eating Behaviors Among College Students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To QG, Frongillo EA, Gallegos D, Moore JB. Household food insecurity is associated with less physical activity among children and adults in the US population. The Journal of nutrition. 2014;144(11):1797-1802.

- Bergmans, R.S.; Coughlin, L.; Wilson, T.; Malecki, K. Cross-sectional associations of food insecurity with smoking cigarettes and heavy alcohol use in a population-based sample of adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 205, 107646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata JM, Palar K, Gooding HC, et al. Food insecurity, sexual risk, and substance use in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68(1):169-177.

- Gundersen, C. Food Insecurity Is an Ongoing National Concern. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2013, 4, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strome S, Johns T, Scicchitano MJ, Shelnutt K. Elements of access: the effects of food outlet proximity, transportation, and realized access on fresh fruit and vegetable consumption in food deserts. International quarterly of community health education. 2016;37(1):61-70.

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.M.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Examining the Association between Food Literacy and Food Insecurity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K.; Wright, R.; Wimer, C. The Cost of Free Assistance: Why Low-Income Individuals Do Not Access Food Pantries. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2016, 43, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An R, Wang J, Liu J, Shen J, Loehmer E, McCaffrey J. A systematic review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA. Public health nutrition. 2019;22(9):1704-1716.

- Rivera, R.L.; Maulding, M.K.; Abbott, A.R.; A Craig, B.; A Eicher-Miller, H. SNAP-Ed (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program–Education) Increases Long-Term Food Security among Indiana Households with Children in a Randomized Controlled Study. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Johnson, M.A.; Brown, A. Older Americans Act Nutrition Program Improves Participants' Food Security in Georgia. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 30, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durward, C.M.; Savoie-Roskos, M.; Atoloye, A.; Isabella, P.; Jewkes, M.D.; Ralls, B.; Riggs, K.; LeBlanc, H. Double Up Food Bucks Participation is Associated with Increased Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Food Security Among Low-Income Adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, J.N.; Raber, M.; Bello, R.S.; Brewster, A.; Caballero, E.; Chennisi, C.; Durand, C.; Galindez, M.; Oestman, K.; Saifuddin, M.; et al. A pilot food prescription program promotes produce intake and decreases food insecurity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmelstein, G. Effect of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansions on food security, 2010–2016. American journal of public health. 2019;109(9):1243-1248.

- Ratcliffe C, McKernan S-M, Zhang S. How much does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program reduce food insecurity? American journal of agricultural economics. 2011;93(4):1082-1098.

- Richardson AS, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Beckman R, et al. Can the introduction of a full-service supermarket in a food desert improve residents' economic status and health? Annals of epidemiology. 2017;27(12):771-776.

- Ledderer, L.; Kjær, M.; Madsen, E.K.; Busch, J.; Fage-Butler, A. Nudging in Public Health Lifestyle Interventions: A Systematic Literature Review and Metasynthesis. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Marshall, A.L.; Miller, Y.D. Behavior Change Interventions Delivered by Mobile Telephone Short-Message Service. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armanasco, A.A.; Miller, Y.D.; Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Marshall, A.L. Preventive Health Behavior Change Text Message Interventions: A Meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, M.F.; Wharton, C. The Design and Testing of a Text Message for Use as an Informational Nudge in a Novel Food Insecurity Intervention. Challenges 2023, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;36(5):452-457.

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of applied social psychology. 2002;32(4):665-683.

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton, Mifflin and Company; 2002.

- Goldrick-Rab S, Clark K, Baker-Smith C, Witherspoon C. Supporting the whole community college student: The impact of nudging for basic needs security. The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. 2021.

- Freedland, K.E.; King, A.C.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Mohr, D.C.; Czajkowski, S.M.; Thabane, L.; Collins, L.M.; Rebok, G.W.; Treweek, S.P.; et al. The selection of comparators for randomized controlled trials of health-related behavioral interventions: recommendations of an NIH expert panel. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2019, 110, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.K.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Bernhardt, J.M. Mobile Text Messaging for Health: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Heal. 2015, 36, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spohr, S.A.; Nandy, R.; Gandhiraj, D.; Vemulapalli, A.; Anne, S.; Walters, S.T. Efficacy of SMS Text Message Interventions for Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2015, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Research Service (ERS). U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2012;https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8271/hh2012.

- Makelarski, J.A.; Abramsohn, E.; Benjamin, J.H.; Du, S.; Lindau, S.T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Two Food Insecurity Screeners Recommended for Use in Health Care Settings. Am. J. Public Heal. 2017, 107, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2021-2022). National Center for Health Statistics. 2022;https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2021-2022/questionnaires/FSQ-FAM-L-508.

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh. Version 28.0. 2021.

- Baraldi, A.N.; Enders, C.K. An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic press; 2013.

- Oronce CIA, Miake-Lye IM, Begashaw MM, Booth M, Shrank WH, Shekelle PG. Interventions to address food insecurity among adults in Canada and the US: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Medical Association; 2021:e212001-e212001.

- Roncarolo, F.; Bisset, S.; Potvin, L. Short-Term Effects of Traditional and Alternative Community Interventions to Address Food Insecurity. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0150250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arizona Department of Economic Security. How to Apply for Nutrition Assistance. https://des.az.gov/how-to-apply-snap#:~:text=Able%2Dbodied%20adults%20without%20dependents%20(ABAWDs)%20are%20only%20eligible,in%20the%20SNA%20E%26T%20program.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits.

- Gregory CA, Coleman-Jensen A. Food insecurity, chronic disease, and health among working-age adults. 2017.

- Nord, M. How much does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program alleviate food insecurity? Evidence from recent programme leavers. PhotoniX 2012, 15, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadurai, V.; Sharf, B.F.; Sharkey, J.R. Rural Food Insecurity in the United States as an Overlooked Site of Struggle in Health Communication. Heal. Commun. 2012, 27, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Zein, A.; Mathews, A.E.; House, L.; Shelnutt, K.P. Why Are Hungry College Students Not Seeking Help? Predictors of and Barriers to Using an On-Campus Food Pantry. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arno, A.; Thomas, S. The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Heal. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, K.J.; Noar, S.M.; Iannarino, N.T.; Harrington, N.G. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurling, R.; Catt, M.; De Boni, M.; Fairley, B.W.; Hurst, T.; Murray, P.; Richardson, A.; Sodhi, J.S. Using Internet and Mobile Phone Technology to Deliver an Automated Physical Activity Program: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med Internet Res. 2007, 9, e633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siopis, G.; Chey, T.; Allman-Farinelli, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for weight management using text messaging. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, E.L.; Fallows, S.; Morris, M. A text message based weight management intervention for overweight adults. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Standard deviations and standard errors. BMJ 2005, 331, 903–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | T1 Total (%) | T2 Total (%) | T3 Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 24 | 16 | 16 |

| Age (Years) | M = 35.9 SD = 15.1 |

M = 39.9 SD = 16.1 |

M = 37.8 SD = 15.2 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 16 (66.7) | 12 (80) | 11 (73.3) |

| Male | 8 (33.3) | 4 (20) | 5 (26.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 6 (25) | 3 (18.75) | 4 (25) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (41.7) | 5 (31.25) | 5 (31.25) |

| White | 5 (20.8) | 5 (31.25) | 4 (25) |

| More Than One Race | 3 (12.5) | 3 (18.75) | 1 (18.75) |

| Income | |||

| < $25,000 | 18 (75) | 12 (75) | 11 (68.75) |

| > $25,000 | 6 (25) | 4 (25) | 5 (31.25) |

| Education | |||

| Less Than High School | 3 (12.5) | 1 (6.25) | 1 (6.25) |

| High School Graduate | 12 (50) | 6 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) |

| Some College | 8 (33.3) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) |

| College Graduate | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.25) | 1 (6.25) |

| Group Status | |||

| Intervention | 12 (50) | 10 (62.5) | 9 (56.25) |

| Control | 12 (50 | 6 (37.5) | 7 (43.75) |

| Food Security Score | M = 8.2, SD = 2.5 | ||

| Past Food Pantry Use | |||

| No | 15 (62.5) | ||

| Yes | 9 (37.5) |

| Outcome | Time Point | Intervention | Control | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Pantry | ||||

| Baseline | 33% Past Use | 44% Past Use | ||

| One Month | h = 0.21 | |||

| 10% No Visits | 16.7% No Visits | |||

| 30% One Visit | 16.7% One Visit | |||

| 60% Two Visits | 66.6% Two Visits | |||

| Two Months | h = 0.18 | |||

| 22.2% No Visits | 14.7% No Visits | |||

| 11.1% One Visit | 14.7% One Visit | |||

| 66.7% Two Visits | 70.6% Two Visits | |||

| SNAP | ||||

| Baseline | 0% Registered | 0% Registered | - | |

| One Month | 0% Registered | 17% Registered | h = 0.85 | |

| Two Months | 0% Registered | 29% Registered | h = 1.14 | |

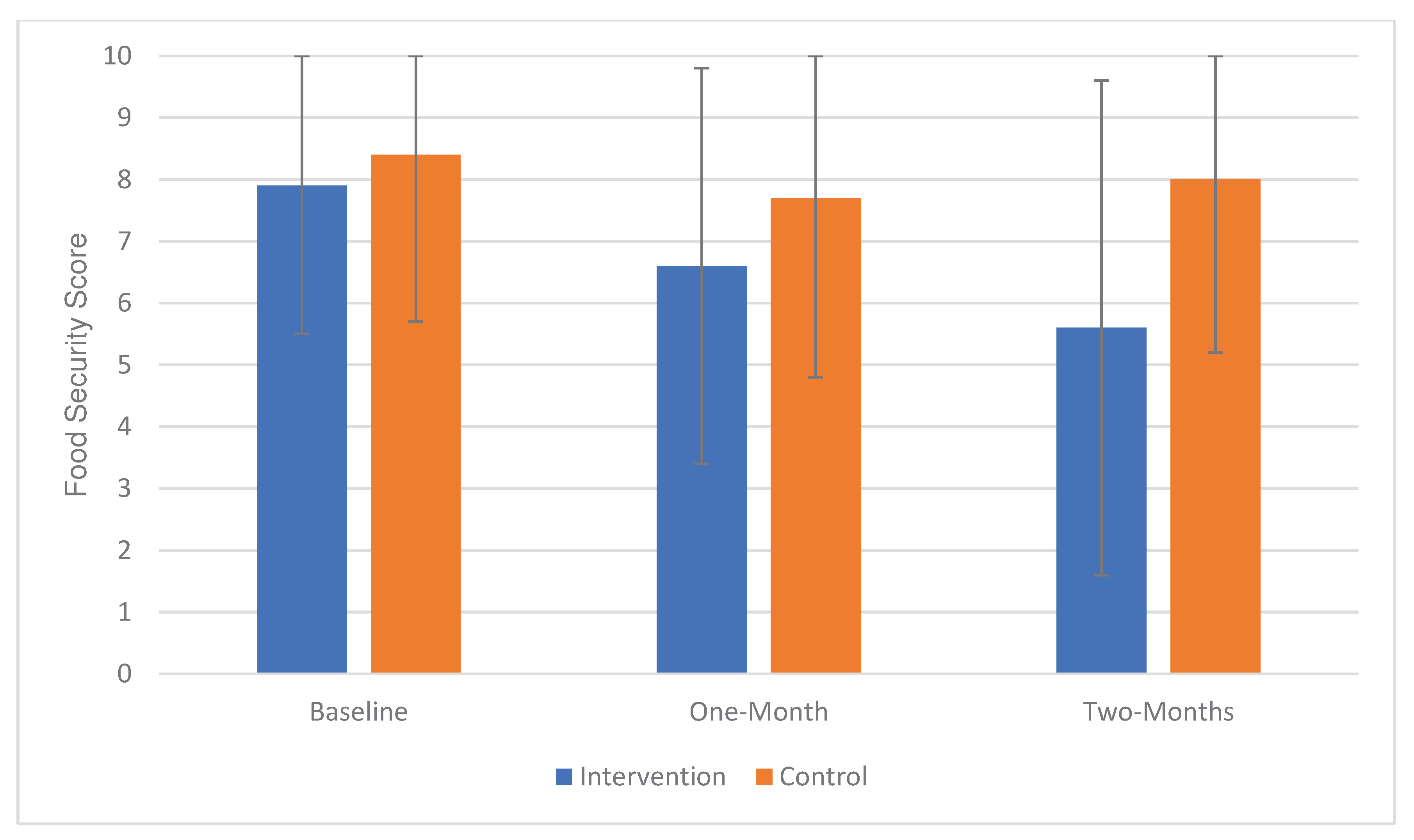

| FS Score | ||||

| Baseline | M = 7.9 SD = 2.4 |

M = 8.4 SD = 2.7 |

||

| One Month | M = 6.6 SD = 3.2 |

M = 7.7 SD = 2.9 |

D = 0.35 | |

| Two Months | M = 5.6 SD = 4.0 |

M = 8.0 SD = 2.8 |

D = 0.71 | |

| FS Status | ||||

| Baseline | 100% Food Insecure | 100% Food Insecure | - | |

| One Month | 80% Food Insecure | 100% Food Insecure | h = 0.93 | |

| Two Months | 56% Food Insecure | 100% Food Insecure | h = 1.45 |

| Outcome | Mean Difference (SE) | 95% CI | t-Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Pantry | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = 0.00, SE = 0.39 | -0.84, 0.84 | t = 0.0 | p = 1 |

| Two Months | D = -0.13, SE = 0.43 | -1.04, 0.78 | t = -0.29 | p = 0.77 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -0.24, SE = 0.32 | -0.97, 0.49 | t = -0.32 | p = 0.76 |

| Two Months | D = -0.11, SE = 0.54 | -1.35, 1.12 | t = -0.40 | p = 0.70 |

| SNAP | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -0.17, SE = 0.17 | -0.56, 0.26 | t = -1.00 | p = 0.36 |

| Two Months | D = -0.29, SE = 0.18 | -0.74, 0.17 | t = -1.56 | p = 0.17 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -0.34, SE = 0.15 | -0.66, -0.10 | t = -2.63 | p = 0.02 |

| Two Months | D = -0.41, SE = 0.22 | -0.91, 0.09 | t = -2.12 | p = 0.05 |

| FS Score | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -1.07, SE = 1.58 | -4.46, 2.33 | t = -0.67 | p = 0.51 |

| Two Months | D = -2.44, SE = 1.69 | -6.07, 1.18 | t = -1.45 | p = 0.17 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -1.50, SE = 0.96 | -3.71, 0.70 | t = -0.40 | p = 0.69 |

| Two Months | D = -1.21, SE = 1.32 | -4.25, 1.84 | t = -0.81 | p = 0.43 |

| FS Status | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -0.20, SE = 0.18 | 0.57, -0.17 | t = -1.15 | p = 0.27 |

| Two Months | D = -0.44, SE = 0.20 | -0.85, -0.01 | t = -2.21 | p = 0.04 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| One Month | D = -0.18, SE = 0.29 | -0.48, 0.84 | t = -0.71 | p = 0.48 |

| Two Months | D = -0.19, SE = 0.26 | -0.77, 0.40 | t = -1.28 | p = 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).