Submitted:

12 February 2024

Posted:

13 February 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Objective

Conceptual Framework

Language

Methods

Identification of Relevant Studies

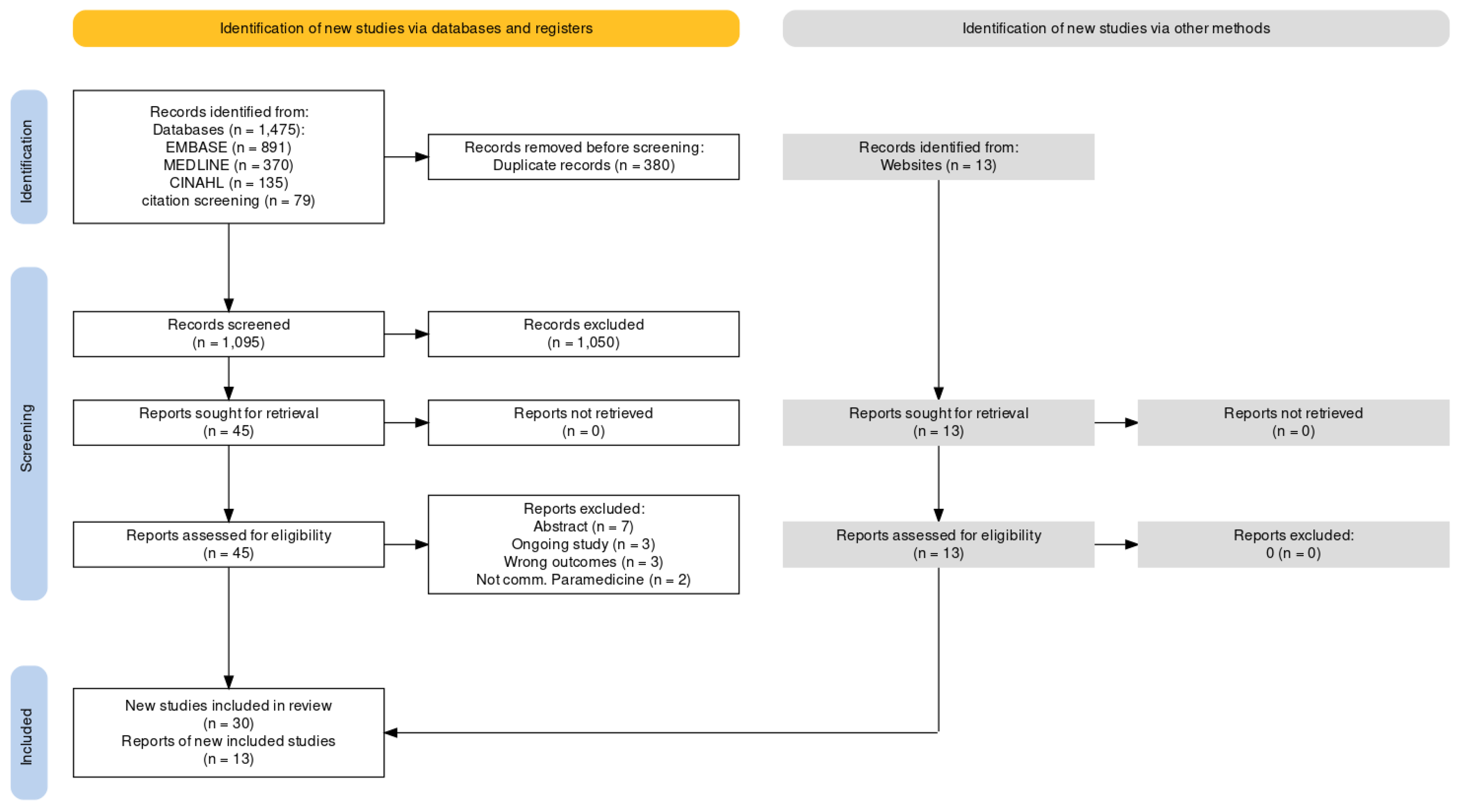

Study Selection

Data Charting

Collating, Summarising, and Reporting Results

Trustworthiness and Rigour

Reflexivity and Positionality

Ethics Approval

Results

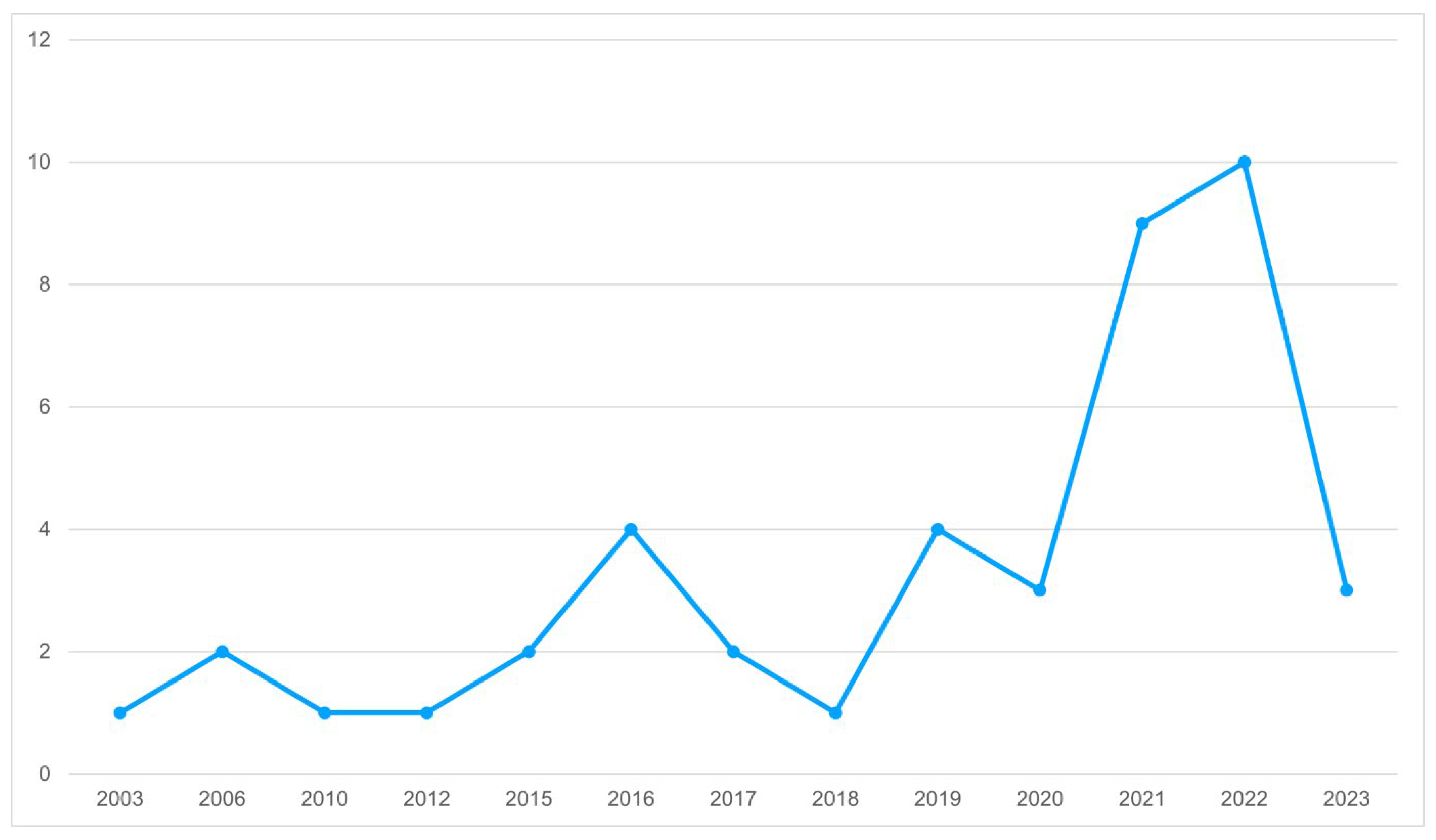

Identification of Potential Studies

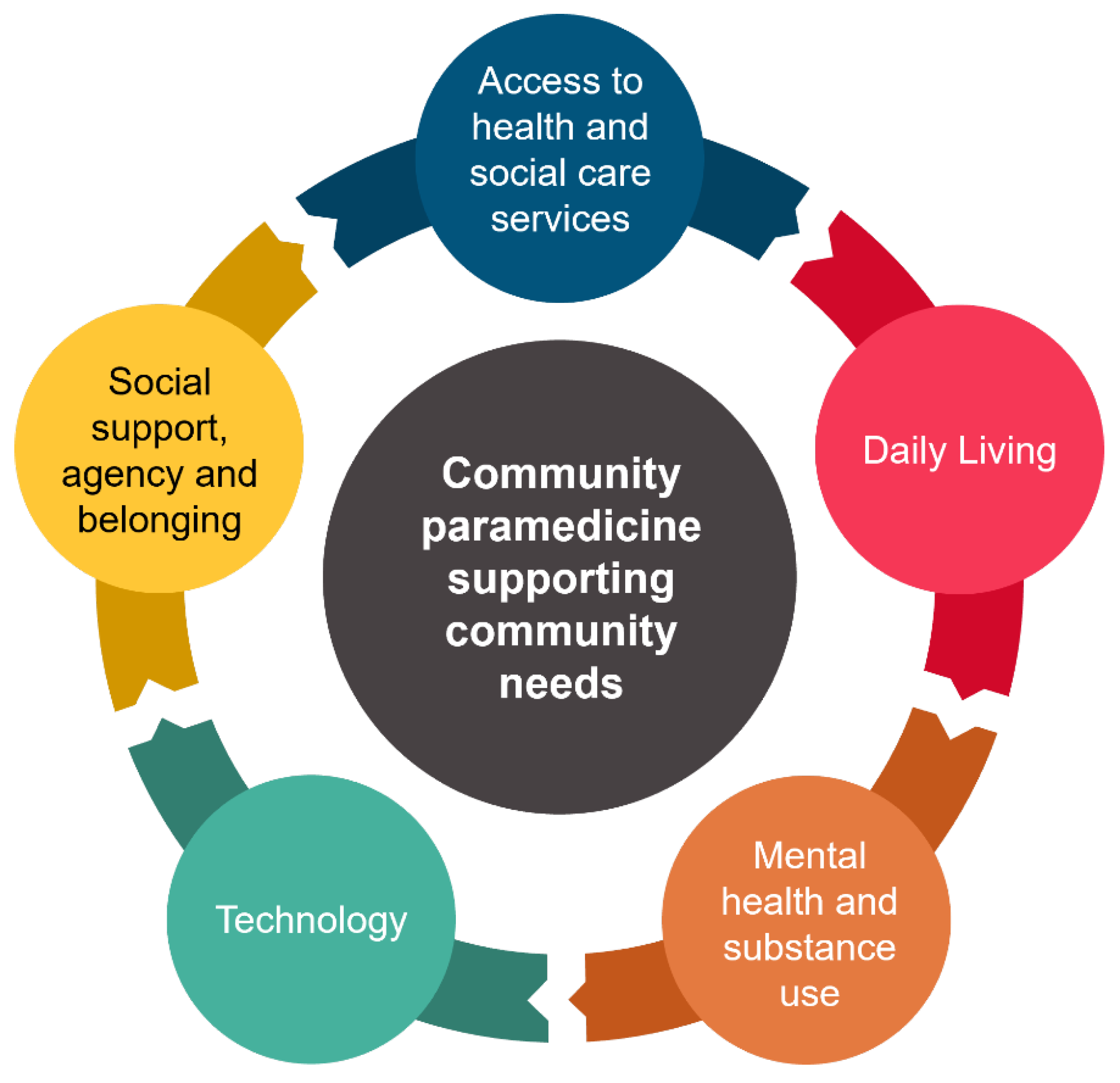

Community Needs Domains

Domain 1 - Access to Health and Social Services

Domain 2 - Daily Living

Domain 3 - Mental Health and Substance Use

Domain 4 - Technology

Domain 5 - Social Support, Agency and Belonging

Community Needs Assessment

Social Needs Education

Discussion

Future Directions

Limitations

Conclusion

Author contributions

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgements

Statements and declarations

References

- Allana, A., & Pinto, A. (2021). Paramedics Have Untapped Potential to Address Social Determinants of Health in Canada. Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé, 16(3), 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, B., Eaton, G., Lanos, C., Leyenaar, M., Nolan, M., Bowles, K.-A., … Batt, A. (2022). The development of community paramedicine; a restricted review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e3547–e3561. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, B., Eaton, G., Lanos, C., Leyenaar, M., Nolan, M., Bowles, K.-A., … Batt, A. (2022). The development of community paramedicine; a restricted review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e3547–e3561. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, B., Batt, A. M., Eaton, G., Bowles, K.-A., & Williams, B. (2021). Community Paramedicine Practice Framework Scoping Exercise. Retrieved from https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeAwoe6hhx3Qzd%252fCRqybt66szE0PsYSC8wDndnJ4ZZBtixIuvZKX1%252f4wN58oIZl8uwPebsYwRo0IvX6hVCWn5T8FxWsBQJfWSaVSf%252bRJ%252b80BMTb0c8d%252b63Hj.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation : health equity through action on the social determinants of health : final report of the commission on social determinants of health. Combler le fossé en une génération : instaurer l’équité en santé en agissant sur les déterminants sociaux de la santé : rapport final de la Commission des Déterminants sociaux de la Santé, 247.

- Essington, T., Bowles, R., & Donelon, B. (2018). The Canadian Paramedicine Education Guidance Document.

- Porroche-Escudero, A. (2022). Health systems and quality of healthcare: bringing back missing discussions about gender and sexuality. Health Systems, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- IISD. (2023, June 7). Who Is Being Left Behind in Canada? International Institute for Sustainable Development. International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.iisd.org/articles/insight/who-being-left-behind-canada.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W., Bowles, R., & Donelon, B. (2016). Informing a Canadian paramedic profile: framing concepts, roles and crosscutting themes. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 477. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W., Allana, A., Beaune, L., Weiss, D., & Blanchard, I. (2021). Principles to Guide the Future of Paramedicine in Canada. Prehospital Emergency Care, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S. A. (2019). The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1637. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., … Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature | CADTH. (n.d.). Retrieved June 11, 2023, from https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters-practical-tool-searching-health-related-grey-literature.

- Haddaway, N. R., Grainger, M. J., & Gray, C. T. (2021, February 16). citationchaser: An R package and Shiny app for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Francis, E. (n.d.). 11.2.8 Analysis of the evidence - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki. Retrieved June 11, 2023, from https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687681.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E., & Magilvy, J. K. (2011). Qualitative Rigor or Research Validity in Qualitative Research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 16(2), 151–155. [CrossRef]

- Batt, A. M., Williams, B., Brydges, M., Leyenaar, M., & Tavares, W. (2021). New ways of seeing: supplementing existing competency framework development guidelines with systems thinking. Advances in Health Sciences Education. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B. (1997). Systems theory. In Theories and practice in social work (In J. Brandall., pp. 3–17). The Free Press.

- Sturmberg, J. P. (2007). Part 1 clinical application. Australian Family Physician, 36(3), 170–173.

- Kannampallil, T. G., Schauer, G. F., Cohen, T., & Patel, V. L. (2011). Considering complexity in healthcare systems. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 44(6), 943–947. [CrossRef]

- Ashton, C., & Leyenaar, M. S. (2019). Health Service Needs in the North: A Case Study on CSA Standard for Community Paramedicine. Canada: Canadian Standards Association. Retrieved from https://www.csagroup.org/wp-content/uploads/CSA-Group-Research-Health-Service-Needs-in-the-North-1.pdf.

- Batt, A. M., Hultink, A., Lanos, C., Tierney, B., Grenier, M., & Heffern, J. (2021). Advances in Community Paramedicine in Response to COVID-19.

- Cockrell, K. R., Reed, B., & Wilson, L. (2019). Rural paramedics’ capacity for utilising a salutogenic approach to healthcare delivery: a literature review. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 16. [CrossRef]

- Misner, D. (2003). Community Paramedicine: A Part of an Integrated Health Care System. Retrieved from https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Expanded%20Role/Community%20Paramedicine.pdf?ver=TfO8p2_1qDzq4LlLyNLlqA%3d%3d.

- Buitrago, I., Seidl, K. L., Gingold, D. B., & Marcozzi, D. (2022). Analysis of Readmissions in a Mobile Integrated Health Transitional Care Program Using Root Cause Analysis and Common Cause Analysis. Journal for Healthcare Quality, 44(3), 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Sokan, O., Stryckman, B., Liang, Y., Osotimehin, S., Gingold, D. B., Blakeslee, W. W., … Rodriguez, M. (2022). Impact of a mobile integrated healthcare and community paramedicine program on improving medication adherence in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after hospital discharge: A pilot study. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy, 8, 100201. [CrossRef]

- Olynyk, C. (2010). Toronto EMS Community Paramedicine Program Overview 2010. Toronto, Canada. Retrieved from https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Expanded%20Role/Toronto%20CREMS/Toronto%20EMS%20Community%20Paramedicine%20Program%20Overview%202010.pdf?ver=Vn9xFmVDYfFxk0pJG0QiFw%3d%3d.

- Taplin, J., Dalgarno, D., Smith, M., Eggenberger, T., & Ghosh, S. M. (2023). Community paramedic outreach support for people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 15(2).

- Schwab-Reese, L. M., Renner, L. M., King, H., Miller, R. P., Forman, D., Krumenacker, J. S., & DeMaria, A. L. (2021). “They’re very passionate about making sure that women stay healthy”: a qualitative examination of women’s experiences participating in a community paramedicine program. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1167. [CrossRef]

- Pennel, C. L., Tamayo, L., Wells, R., & Sunbury, T. (2016). Emergency Medical Service-based Care Coordination for Three Rural Communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(4A), 159–180. [CrossRef]

- Ruest, M. (2016). County of Renfrew Paramedic Service Resilience Program Contribution to the Health Promotion Strategies that Address the Inequities Associated with Social Isolation of Seniors in the County of Renfrew. Canadian Paramedicine, 39(3).

- Boland, L. L., Jin, D., Hedger, K. P., Lick, C. J., Duren, J. L., & Stevens, A. C. (2022). Evaluation of an EMS-Based Community Paramedic Pilot Program to Reduce Frequency of 9-1-1 Calls among High Utilizers. Prehospital Emergency Care, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, R., Stryckman, B., & Velez, R. (2019). The Integral Role of Nurse Practitioners in Community Paramedicine. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(10), 725–731. [CrossRef]

- Langabeer, J. R., Persse, D., Yatsco, A., O’Neal, M. M., & Champagne-Langabeer, T. (2021). A Framework for EMS Outreach for Drug Overdose Survivors: A Case Report of the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System. Prehospital Emergency Care, 25(3), 441–448. [CrossRef]

- Logan, R. I. (2022). ‘I Certainly Wasn’t as Patient-Centred’: Impacts and Potentials of Cross-Training Paramedics as Community Health Workers. Anthropology in Action, 29(3), 14–22. [CrossRef]

- McManamny, T. E., Boyd, L., Sheen, J., & Lowthian, J. A. (2022). Feasibility and acceptability of paramedic-initiated health education for rural-dwelling older people. Health Education Journal, 81(7), 848–861. [CrossRef]

- Moczygemba, L. R., Thurman, W., Tormey, K., Hudzik, A., Welton-Arndt, L., & Kim, E. (2021). GPS Mobile Health Intervention Among People Experiencing Homelessness: Pre-Post Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(11), e25553. [CrossRef]

- Mund, E. (2016). Taking Care to the Streets. EMSWorld. Retrieved from https://lw.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/emsworld/article/12179630/taking-mih-cp-care-to-the-streets.

- Rahim, F., Jain, B., Patel, T., Jain, U., Jain, P., & Palakodeti, S. (2022). Community Paramedicine: An Innovative Model for Value-Based Care Delivery. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Gainey, C. E., Brown, H. A., & Gerard, W. C. (2018). Utilization of Mobile Integrated Health Providers During a Flood Disaster in South Carolina (USA). Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 33(4), 432–435. [CrossRef]

- Taplin, J. G., Barnabe, C. M., Blanchard, I. E., Doig, C. J., Crowshoe, L., & Clement, F. M. (2022). Health service utilization by people experiencing homelessness and engaging with community paramedics: a pre–post study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(8), 885–889. [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, J. L., Wissler Gerdes, E. O., Zhu, X., Finnie, D. M., Wiepert, L. M., Glasgow, A. E., … McCoy, R. G. (2023). A Community Paramedic Clinic at a Day Center for Adults Experiencing Homelessness. NEJM Catalyst, 4(4). [CrossRef]

- Stickler, Z. R., Carlson, P. N., Myers, L., Schultz, J. R., Swenson, T., Darling, C., … McCoy, R. G. (2021). Community Paramedic Mobile COVID-19 Unit Serving People Experiencing Homelessness. The Annals of Family Medicine, 19(6), 562–562. [CrossRef]

- Strum, R. (2015). Paramedics as Health Advocates. Canadian Paramedicine, 38(6).

- Thomas-Henkel, C., & Schulman, M. (n.d.). Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Populations with Complex Needs: Implementation Considerations.

- Pirrie, M., Harrison, L., Angeles, R., Marzanek, F., Ziesmann, A., & Agarwal, G. (2020). Poverty and food insecurity of older adults living in social housing in Ontario: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1320. [CrossRef]

- Leyenaar, M. S., McLeod, B., Jones, A., Brousseau, A.-A., Mercier, E., Strum, R. P., … Costa, A. P. (2021). Paramedics assessing patients with complex comorbidities in community settings: results from the CARPE study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(6), 828–836. [CrossRef]

- Ford-Jones, P. C., & Daly, T. (2022). Filling the gap: Mental health and psychosocial paramedicine programming in Ontario, Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(2), 744–752. [CrossRef]

- Newall, N. (2015). Who’s At My Door Project: How organizations find and assist socially isolated older adults (p. 44). Winnipeg, Manitoba: Centre on Aging. Retrieved from https://umanitoba.ca/centre-on-aging/sites/centre-on-aging/files/2021-02/centre-aging-research-publications-report-who%27s-at-my-door-project.pdf.

- Nolan, M., Hillier, T., & D’Angelo, C. (2012). Community Paramedicine in Canada. Retrieved from https://ircp.info/Portals/11/Downloads/Policy/Comm%20Paramedicine%20in%20Canada.pdf?ver=XJMZv0HNBUMEpxqc9etOFg%3d%3d.

- Naimi, S., Stryckman, B., Liang, Y., Seidl, K., Harris, E., Landi, C., … Gingold, D. B. (2023). Evaluating Social Determinants of Health in a Mobile Integrated Healthcare-Community Paramedicine Program. Journal of Community Health, 48(1), 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Raven, S., Tippett, V., Ferguson, J.-G., & Smith, S. (2006). An exploration of expanded paramedic healthcare roles for Queensland (p. 100). Queensland, Australia: Australian Centre for Prehospital Research. Retrieved from https://ircp.info/portals/11/downloads/expanded%20role/queensland%20expanded%20role.pdf.

- Hay, D., Varga-Toth, J., & Hines, E. (2006). Frontline Health Care in Canada: Innovations in Delivering Services to Vulnerable Populations (Rresearch Report No. F, 63) (p. 96).

- PHECC. (2020). The introduction of Community Paramedicine into Ireland. Retrieved from https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeDKMmmW%252fnE3lbsxRkYxd6aQYk7snfcymr0EG16DvMZvqmNsz5SqfTY2bCjDsrkmvfchr0f6fWdxsRfEpP0eHF2WFYnnA1HA6sq8buhbiuE7hUxFSMEFO%252btRyWB31RTiP1quSbFCsa%252bZGt6Ri4g1h1nnWZcXksZCSqw%253d.

- Hirello, L., & Cameron, C. (2021). Improving Paramedicine through Social Accountability. Canadian Paramedicine, 44(3). Retrieved from https://canadianparamedicine.ca/special-editions/.

- Chan, J., Griffith, L. E., Costa, A. P., Leyenaar, M. S., & Agarwal, G. (2019). Community paramedicine: A systematic review of program descriptions and training. CJEM, 21(6), 749–761. [CrossRef]

- PHECC. (2022). Community Paramedicine in Ireland: a framework for the specialist paramedic. Retrieved from https://www.phecit.ie/Custom/BSIDocumentSelector/Pages/DocumentViewer.aspx?id=oGsVrspmiT0dOhDFFXZvIz0q5GYO7igwzB6buxHEgeDq00klOJxrAiwRg8WilA7iQpuh0JuuyxLZ%252fgoqHj9YAdVJBi%252feIjLQQQejAdgErxHc1gOlnYuCfGcZtM%252fFZTDuGELCeo4hOpwR2WpMNptaZMMl%252biPM01lTiSTAjYn0UiWidbzfXGJzNluN5VUHbqIsRWHtJZQ5aTg%253d.

- Agarwal, G., Lee, J., McLeod, B., Mahmuda, S., Howard, M., Cockrell, K., & Angeles, R. (2019). Social factors in frequent callers: a description of isolation, poverty and quality of life in those calling emergency medical services frequently. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 684. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G., & Brydges, M. (2018). Effects of a community health promotion program on social factors in a vulnerable older adult population residing in social housing. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 95. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G., Keenan, A., Pirrie, M., & Marzanek-Lefebvre, F. (2022). Integrating community paramedicine with primary health care: a qualitative study of community paramedic views. CMAJ Open, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Group, C. (2023). Canadian Paramedic Landscape Review and Standards Roadmap. Retrieved from https://www.csagroup.org/wp-content/uploads/CSA-Group-Research-Canadian-Paramedic-Landscape-Review-And-Standards-Roadmap.pdf.

- Bolster, J., Batt, A. M., & Pithia, P. (2022). Emerging Concepts in the Paramedicine Literature to Inform the Revision of a Pan-Canadian Competency Framework for Paramedics: A Restricted Review. [CrossRef]

- First Nation Information Governance Centre. (n.d.). OCAP Principles. The First Nations Information Governance Centre. Canada. Retrieved June 11, 2023, from https://fnigc.ca/.

- Rosa, A., Dissanayake, M., Carter, D., & Sibbald, S. (2022). Community paramedicine to support palliative care. Progress in Palliative Care, 30(1), 11–15. [CrossRef]

- Group, C. (2017). Community paramedicine: Framework for program development. Canada. Retrieved from https://www.csagroup.org/store-resources/documents/codes-and-standards/2425275.pdf.

- Gebhard, A., McLean, S., & St Denis, V. (2022). White benevolence: racism and colonial violence in the helping professions. Canada: Fernwood Publishing Company.

- O’Meara, P., Ruest, M., & Stirling, C. (2014). Community Paramedicine: Higher Education as An Enabling Factor. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- NAEMSE. (2023). NAEMSE Consensus Statement on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging. Prehospital Emergency Care. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10903127.2023.2212753?download=true.

- Alsan, M., Garrick, O., & Graziani, G. (2019). Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. American Economic Review, 109(12), 4071–4111. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, R. P., Krebs, W., Cash, R. E., Rivard, M. K., Lincoln, E. W., & Panchal, A. R. (2020). Females and Minority Racial/Ethnic Groups Remain Underrepresented in Emergency Medical Services: A Ten-Year Assessment, 2008–2017. Prehospital Emergency Care, 24(2), 180–187. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, K. M., Arora, T. K., Termuhlen, P. M., Stain, S. C., Misra, S., Dent, D., & Nfonsam, V. (2021). Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Medicine: Why It Matters and How do We Achieve It? Journal of Surgical Education, 78(4), 1058–1065. [CrossRef]

- Rudman, J. S., Farcas, A., Salazar, G. A., Hoff, J., Crowe, R. P., Whitten-Chung, K., … Joiner, A. P. (2023). Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the United States Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Emergency Care, 27(4), 385–397. [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J. M., & Hansen, H. (2014). Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E. G., Isom, J., DeBonis, K. L., Jordan, A., Braslow, J. T., & Rohrbaugh, R. (2020). Reconsidering Systems-Based Practice: Advancing Structural Competency, Health Equity, and Social Responsibility in Graduate Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 95(12), 1817–1822. [CrossRef]

- Coletto, D. (2023, June 8). Canadians Are Ready for Paramedics to Do More in Healthcare: Abacus Data Poll. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://abacusdata.ca/pac-2023/.

- Allana, A., Tavares, W., Pinto, A. D., & Kuluski, K. (2022). Designing and Governing Responsive Local Care Systems – Insights from a Scoping Review of Paramedics in Integrated Models of Care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 22(2), 5, 1–19. https://doi. org/10.5334/ijic.6418.

- Taplin, J. G., Bill, L., Blanchard, I. E., Barnabe, C. M., Holroyd, B. R., Healy, B., & McLane, P. (2023). Exploring paramedic care for First Nations in Alberta: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open, 11(6), E1135–E1147. [CrossRef]

- Allan, B. (2015). First Peoples, Second Class Treatment. Toronto: Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute. Retrieved from https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf.

| Country | Number of studies n (%) |

|---|---|

| Canada | 19 (44) |

| United States of America | 17 (39) |

| Australia | 5 (12) |

| Ireland | 2 (5) |

| Total | 43 |

| Domain | Domain 1 - Access to Health and Social Services | Domain 2 - Daily Living | Domain 3 - Mental Health and Substance Use | Domain 4- Technology | Domain 5- Social Support, Agency and Belonging | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of studies n= 43 | n=42 | n=30 | n=28 | n=3 | n=33 | |

| Included codes |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).